CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old male patient presented with bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain in November 2001. No laboratory alterations were present (including serum carcinoembryonic antigen and CA19-9). Colonoscopy and biopsy established the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (proctosigmoiditis). The disease activity was moderate at the beginning. Abdominal sonography (US) revealed normal findings. Mesalazine was started orally along with regular follow-up 11 mo.

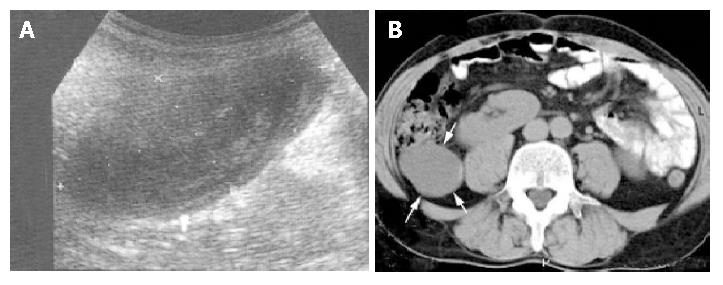

The disease was in remission until November 2003, when he was admitted to our Outpatient Clinic with upper and right lower abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. Colonoscopy found proctosigmoiditis with a moderate activity, gastroscopy revealed chronic gastritis, laboratory data was normal (sedimentation (ESR): 17 mm/h, CRP: 3 mg/L, leucocytes: 8.0 g/L, haemoglobin: 145 g/L, platelets: 281 g/L). Treatment was amended with mesalazine clysma and methylprednisolone (16 mg) orally. Symptoms ameliorated; however, right lower abdominal pain persisted, which raised the possibility of Crohn’s disease. One wk later abdominal US and CT examination demonstrated a pericecal cystic mass (11 cm×3.5 cm, Figure 1). At first a pericecal abscess was suspected, as the previous US examination (6 mo earlier) had revealed normal findings. Fine needle aspiration was performed. Cytology confirmed the diagnosis of mucocele.

Figure 1 Manifestations of appendiceal mucocele.

A: Peculiar internal echogenicity of onion skin design, occupying a part of the cavity in appendiceal mucocele; B: Presence of a pericaecal 11 cm×3.5 cm cystic lesion in the right lower abdomen (arrows) shown by axial CT.

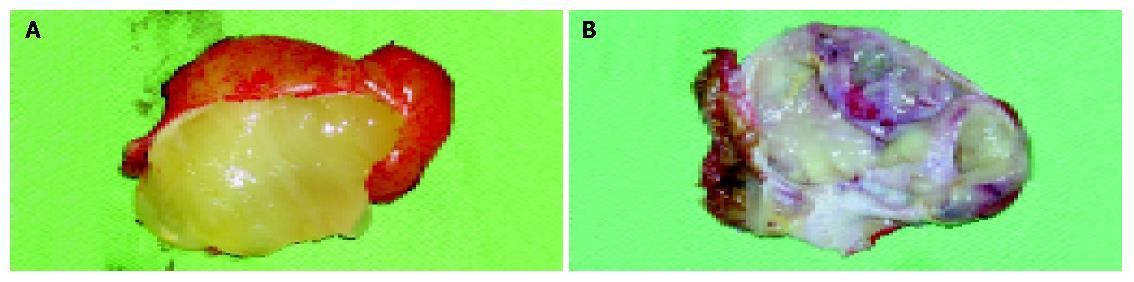

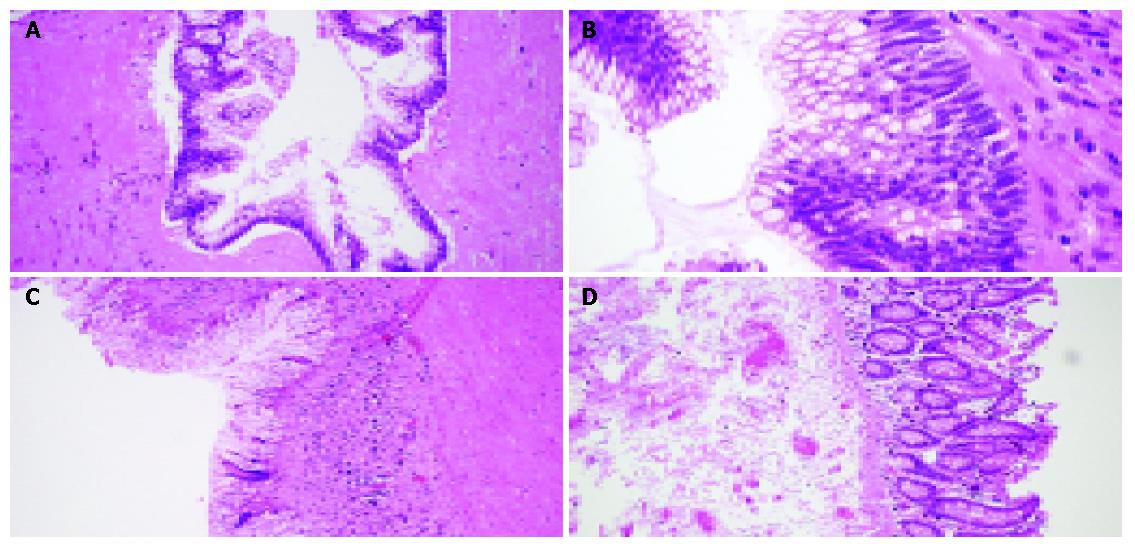

The patient underwent partial cecum resection and extirpation of the mucocele in December 2003 (Figure 2). He recovered well and the final histology revealed cystadenoma (mucinous tumor of unknown malignant potential) of the appendix (Figure 3). Follow up was started. The patient is now free of symptoms. The laboratory and abdominal US findings after 1 and 3 mo were normal with no signs suggesting the spread of mucocele. The colitis of the patient was in remission.

Figure 2 Findings in mucocele at operation.

A: Macroscopic finding in the mucocele at operation; B: Internal part of the cyst after opened.

Figure 3 Histological findings.

A and B: Appendix, mucin-filled lumen lined with atypical mucin-producing columnar epithelium and no infiltration in muscular wall, H&E, ×40, ×60; C: Submucosa loaded with chronic inflammatory cells, H&E, ×20; D: Normal colonic mucosa in the cecum, and thickened submucosa, H&E, ×20.

DISCUSSION

AM is a descriptive term for mucinous distension of the appendiceal lumen regardless of the underlying pathology. Four causal pathologic conditions have been reported: retention cyst, mucosal hyperplasia, cystadenoma (or mucinous tumor of unknown malignant potential) and cystadenocarcinoma[3]. The external appearance is gross enlargement of the appendix, the lumen is distended by mucin. Previous studies reported that the male-to-female ratio was 3-4 to 1 with a mean age of 55 years at diagnosis[5]. Recent reports, however showed a distinct male predominance (4:1)[3], and in a retrospective study of 135 surgically resected patients 55% of the patients were females[6], such that the sex predominance seems to be changing.

Clinical manifestations include palpable abdominal mass, gastrointestinal bleeding and lower right abdominal pain, as in our case[3,5]. Thus, although it is nonspecific, when a mass is palpable or detected incidentally by imaging studies in the lower right abdomen in a patient without a history of appendectomy, we must consider the possibility of AM. Other signs reported in some cases include weight loss, nausea/vomiting, acute appendicitis, changes in bowel habits, and unexplained anaemia[6]. The presence of cutaneous fistula, intussusception and mucus outflow from the appendiceal orifice during colonoscopy was also reported[7-9]. Symptomatic patients were reported, more likely, to have a malignant disease. There have been reports of other tumors associated with AM, including gastrointestinal tract, ovary, breast and kidney tumors, which might occur in up to one-third of the patients[5,6]. The most common association was colorectal cancer. Whether AM represents an increased risk for colorectal cancer is unknown.

The diagnosis is difficult on imaging studies; up to 60% of the cases may be only diagnosed during operations for some other diseases. Preoperative diagnosis is important, alerting the surgeon of an unintended rupture during surgery and avoiding the development of pseudomyxoma peritonei. US and CT were reported to be valuable[3,5,10]. US could show an elongated echo-poor mass, slightly different from what one would expect for a cyst. Fine echo spots and/or concentric, echogenic layers within the cystic mass (“onion skin”, Figure 1) are thought to be specific alteration[1]. The reason for the layered appearance is unclear; one may suggest that fluctuations of the concentration of mucin are responsible for this phenomenon either by fluctuation in the secretion of mucin into the cavity along with gradual absorption of water or by fluctuation of the degree of excretion blockage from the cavity. Most cases did not show posterior echo enhancement. CT is also effective in the evaluation of these neoplasms[10,11]. Furthermore, CT allows a precise observation of the relation between the lesion and the neighbouring organs, and helps rule out or confirm the diagnosis. In suspected AM cases fine needle aspiration should be avoided to preserve integrity of the cyst.

Surgical resection is the current method of choice in the management of AM[6]. Open surgery was performed in most of the cases: appendectomy alone or combined with right hemicolectomy and in some female patients also bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or total abdominal hysterectomy were performed. Laparoscopic resection of AM was also reported[12], however, laparoscopic dissection, by grasping of the appendix specimen, pneumoperitoneum, and transport of the specimen through the abdominal wall might contribute to peritoneal dissemination of an appendiceal mucinous tumor[2]. Peritoneal dissemination from AM was not regarded as a problem with open appendectomy, along with long survival in these patients. The overall 5-year survival was reported to be 55% in 94 unselected AM patients (22 patients had pseudomyxoma peritonei)[13]. However, this was stage dependent: stage A 100%, stage B 67%, stage C 50% and stage D 6%. The survival rate was superior after right hemicolectomy versus appendectomy alone (68% vs 20%).

Pseudomyxoma peritonei were more common in malignant AM. Malignant AM was present in 95% of the pseudomyxoma peritonei cases, while in only 13% of patients without this complication. The crucial issue in this clinical setting was that both histologically benign and malignant cases could result in diffuse mucinous peritoneal tumors. These mucinous peritoneal tumors represented bad prognosis even with extensive treatments, including radical surgical excision and adjuvant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy[14]. The five-year survival rate, depending on whether the disease was benign or malignant, was about 53-75%, however, median survival was about 2 years if only surgical management was performed.

The question arises whether there is a direct link between IBD and AM. IBD is associated with more than one hundred extraintestinal manifestations, including the elevated risk for some gastrointestinal cancers, also possible for AM. Some authors have suggested that the appendix or the appendiceal orifice might be involved in UC, also in distal UC cases[15,16]. It may be hypothesized that in cases with appendiceal involvement, the inflamed orifice may block excretion from the cavity. The role of common immunologic or genetic changes might also be suspected. Two patients with UC and appendiceal cystadenocarcinoma have also been reported, however, a causative role for UC has not been established[17,18].

In conclusion, special attention should be paid to patients with extraordinary symptoms during follow up even in IBD patients with established diagnosis. Unusual symptoms during flare-up should be investigated thoroughly. Although primary adenocarcinoma of the appendix is uncommon, often an incidental finding on imaging examinations and preoperative diagnosis of the mucocele is important for patient management. Recognition of the sonographic onion skin sign in a cystic mass in the right lower quadrant may facilitate the more accurate diagnosis of AM.