Published online Jan 21, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.451

Revised: November 26, 2003

Accepted: March 2, 2004

Published online: January 21, 2005

AIM: To evaluate the effects of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) in patients with malignant esophageal obstruction and to analyze their prognosis and complications.

METHODS: Seventy-four metallic stents were placed under fluoroscopic guidance in 66 patients with esophageal obstruction secondary to carcinoma, of whom, 6 cases were complicated by fistula.

RESULTS: After seventy-two stents were successfully used in 66 cases without any severe complications (technical successful rate was 97%), the dysphagia score improved from 3.3±0.6 to 0.8±0.5 (P<0.01), and life quality improved significantly in all these patients. All fistulae were sealed immediately after coated stents were inserted in the six patients. New stents were placed in two patients: the stent migrated more than 2 cm, in one patient and the stent slipped into stomach in the other. Minor bleeding was found only in 28 patients during the operation. Reobstruction was found in 12 patients, but was successfully cured under endoscopy. The survival rate was 78%, 57% and 11% for 6 mo, 1 year and 2 years respectively.

CONCLUSION: Placement of SEMS is a simple, safe, quick and efficient surgical method for treating esophageal carcinoma obstruction. It may be used mainly as a palliative treatment of esophageal obstruction secondary to carcinoma.

- Citation: Yang HS, Zhang LB, Wang TW, Zhao YS, Liu L. Clinical application of metallic stents in treatment of esophageal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(3): 451-453

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i3/451.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.451

The first successful insertion of an esophageal tube was reported by Sir Charles Symonds in 1887 and was followed by the development of plastic esophageal tubes. The expanding spiral used for treatment of malignant dysphagia by Frimbeger in 1983 was probably the first expanding stent ever used in patients. In recent years, this method has been widely used in esophageal carcinoma obstruction. In this study, we analyzed our clinical cases and evaluated the clinical effects of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) and the improved life quality of patients.

Sixty-six patients (38 males and 28 females, aged 38 to 82 years, mean age 52.7±8.5 years) with esophageal carcinoma were referred for insertion of metallic stents from October 1997 to June 2002. Among the patients, we found strictures were secondary to squamous carcinoma (43 cases), adenocarcinoma (15 cases) and anastomotic recurrence of tumor (8 cases). Each patient was diagnosed at the third or fourth stage of their disease by barium study, CT, MRI, endoscopy and pathology. The degree of dysphagia was graded as the following: 0 = no dysphagia, 1 = being able to swallow most solid foods, 2 = being able to swallow semisolid foods, 3 = being able to swallow liquids only, 4 = complete obstruction. Among the patients, 42 were at grade 3 and 24 were at grade 4. The strictures had a mean length of 75±8 mm (range, 60-170 mm), 5 patients had tracheoesophageal fistulae, and one patient had pleuroesophageal fistulae. Eight tumors were localized in the proximal, 48 in the middle and 10 in the distal third of esophagus. And different degrees of malnutrition were found in all patients.

Seven coated stents and sixty-five uncoated stents, with a length between 80 mm to 150 mm (average 110±10 mm), a diameter between 10 mm to 20 mm were used. A dental pad, a J shape guide wire of 0.038 inch diameter and 90 cm length, an exchange wire of 180 cm or 260 cm length, a 5F Cobra catheter and stent delivery system were used.

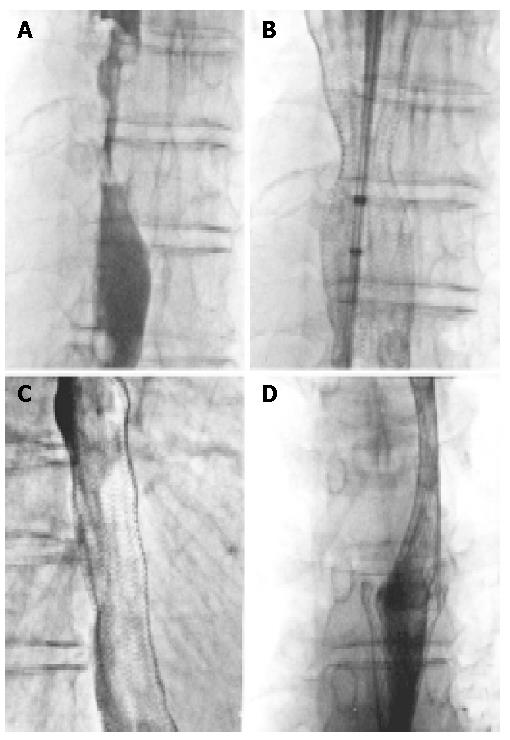

With patients in supine position or lateral recumbent position on the surgical bed, esophagography with water-soluble contrast material was done first to confirm the position and length of strictures, which were marked on corresponding sites with a needle. The stents chosen were at least 4 cm longer than the length of the stricture. Local anesthetic (10 g/L dicaine) was applied to the mouth and throat. Stent insertion was performed under fluoroscopic guidance. J shape guide wire and 5 F Cobra catheter were inserted into the stomach first, then exchange wire was inserted and the stent delivery system was passed through the stricture site with the stent released at the exact position. The shape and position of the stent were observed immediately with water-soluble contrast material esophagography. If the stricture was too long, another stent was inserted when necessary with an overlap of the two stents over 2 cm (Figure 1).

Fasting during the first 24 h was necessary and gentamicin sulfate was given by oral administration to prevent infection. Liquid food was first given in the following day, and then semisolid food and solid food were given. The time to begin normal food in those patients who had a coated stent inserted depended on the position and degree of stent expanding. Barium study was usually made on the second day and further esophagography should be done in a week if the stent was not fully expanded. Survivors should be followed up for at least 24 mo.

Seventy-four stents were used in 66 patients with esophageal carcinoma obstruction. Second stents were inserted in 6 patients. Stent migrated down in one patient after insertion and another one was inserted above it. A second stent was placed at the exact position because the first one slipped into stomach in another patient. The rate of correct placement was 97% (72/74). After operation, 55 stents were fully expanded within three days, and the other 19 stents were fully expanded just in one week. Dysphagia was obviously palliated in all patients with the dysphagia score reduced to grade 0-1. Fistulae in 6 patients disappeared immediately after coated stents were inserted in the right position, and symptoms such as cough and fever were palliated in two weeks. General conditions improved in one mo except in three cases. Almost all patients experienced chest pain and abnormal feeling in throat after stents were inserted. Eighteen of them required treatment with analgesics, but abnormal feeling in the throat persisted for a long time and then alleviated or disappeared in one or two mo especially in those patients with a stent in proximal esophageal lesions. Minor bleeding was found in 28 patients during operation and was not treated. Stent migration occurred in two patients, the stent migrated less than 2 cm out of the lumen in one patient and no treatment was done for it. In the other patient, a second stent was used. Reobstruction occurred in 12 patients. It was due to food obstruction in 4 cases, tumor tissue growth in stents in 7 cases, and stricture of esophagus at the edges of stent by overgrowth of benign tissue in 1 case respectively. All of them were successfully treated gastroscopically. A stent was slipped into stomach after insertion, and another stent was put in correct position. Before the stent in stomach was treated, this patient died of cachexia in one mo. Seven patients survived for over 24 mo, 27 for over 12 mo, 18 for over 6 mo, 11 for over 1 mo and 3 died in 1 mo. Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy were practiced after stent insertion in 8 patients, of whom, 6 survived for over 1 year, and 2 for over 2 years.

Many patients suffered from severe malnutrition due to dysphagia of terminal esophageal carcinoma. It was reported[1] that 60-65% patients had malnutrition due to pancreatic carcinoma, esophageal cancer or gastrointestinal carcinoma, and many of them had lost the chance for surgical operation. Endoscopic laser therapy (ELT), electrocautery, metallic or plastic esophageal stent could alleviate their clinical symptoms, but metallic stent placement was much more effective[2]. Gevers et al[3] compared ELT, plastic stents and metallic stents in treatment of malignant obstruction and found that plastic stents were used less because of its high complication rate and short palliation time. ELT was the preferred choice in patients who had a short prospective survival time for its low complication rate. Metallic stents should be used for those patients who had ELT failure, fistulae or a long prospective survival time. If expandable metal stents with a small diameter passed the stricture easily, aggressive dilation of the esophagus before or after deployment was unnecessary. This might reduce the suffering and financial burden of patients. Such advantages are obvious for low complication rate and retreatment times. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy require a relatively long time before any effect on dysphagia is achieved. The effect of dilation or ELT is relatively short and the treatment must be repeated frequently in many patients. Metallic stent wire could attach closely to the esophageal wall, making it difficult to slip down, and minor damage to tissue might occur around it[4]. Coated stents could seal fistulae immediately after insertion, control pulmonary infection of patients and improve their general conditions. Coated expandable metal stent might increase survival times of patient with tracheoesophageal fistula or pleuroesophageal fistula compared to other therapies[2,5]. Six patients with fistulae in our study were cured providing a proof of its effect.

Metallic stents are most suitable for the middle thirds of esophageal lesions. Stricture at the gastroesophageal junction is amenable to stent insertion with a high rate of technical and clinical success. But severe reflux and aspiration might happen, and a one-way flap valve on the gastric side of the stent could prevent those complications[6-8]. Insertion of a metallic stent in the proximal esophageal lesion is technically difficult. However, in some reports, the upper edges of stents lay in C4 -T5 level and no severe complications were found except abnormal feeling in throat; dysphagia was palliated obviously after stents were successfully inserted[9].

There are different opinions on the necessity of balloon dilation before and after stent insertion. Cwikiel et al[10] reported that it could reduce the rate of migration by dilation after stent insertion. Our experiment found that balloon dilation was unnecessary if the delivery system could pass through the stricture lesion. The key for preventing immediate post-procedural complications is to change patients’ habit of diet. They should not take cold food, slabby food, big block food and long-fibrous food. Most of stents were fully expanded in one week after insertion and the stent wire was incorporated into the tumor and normal esophageal walls. The time to take food relies on the results of esophageal radiography. As to coated stents, there is a lumen between stent and esophageal wall, infection might occur due to the food stuck in the lumen if food is taken too early. Coated stent tends to migrate or slip down for its surface is smooth and the stents do not incorporate into the normal wall before it is fully expanded.

There are few reports on cost comparison between metallic stent and ELT for the treatment of esophageal obstruction. Despite the substantially higher cost of metallic stent placement, substantial overall cost could be saved due to the reduction of re-treatment and hospitalization because of complications[11,12]. As for the clinical application of coated stents, it should be only used in esophageal carcinoma with fistula and perforation, since it is unable to prevent restricture entirely, and can increase the chance of migration and infection.

Restrictures were often found resulting from tumor overgrowth or growth through the stent meshes or benign hyperplasic tissues at the edge of stents discovered during long-term follow up[9,13]. A coated stent placement may prevent tumor ingrowth, but cannot prevent overgrowth of tumors and benign hyperplasic tissues at the edge of stents, but a secondary stent insertion may solve this problem. With stents confined, the risk of perforation and bleeding was low, and ELT or electrocautery might be another good choice[7].

Placement of esophageal metallic stent could lead to many complications. Maier[14] reported that there was a high mortality in patients who were inserted esophageal stents (3-29 d) soon after balloon dilation, local hyperthermia, ELT, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or radio-chemotherapy. Postmortem examination confirmed that the pressure of fully expanded stents to the esophageal wall caused the rupture, and weakness of the esophageal wall might be the main reason. Fatal hemorrhage was reported after metallic stent insertion[15], necrosis of the esophageal and aorta walls at the edge of stent was confirmed to be the reason by postmortem examination. Other reports[16] argued that hemorrhage was the complication of esophageal carcinoma invading the wall of aorta, and stent insertion induced its rupture or hemorrhage. An overall understanding of the treatment of patients before stent insertion is necessary and the prognosis of stent placement should be estimated correctly. Nasogastric tube placement or ELT is the first choice for those patients in poor general condition and with a short prospective survival time. At the beginning of our study, stents were inserted in 3 patients at the terminal stages of their diseases and in poor general condition, all the patients died in one mo due to loss of appetite and cachexia. Before stent insertion, epiglottis dysfunction and severe pulmonary infection and cough due to aspiration should be diagnosed for the patients. Nasogastric tube placement or gastrostomy should be performed for those patients to solve the problem of taking food[15].

If the condition of patients permitted, radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy followed by stent insertion were necessary but adjustment of radiation therapy plan was unnecessary in those patients. In our study, chemotherapy infusion was done in two patients after stent placement at intervals of 3 or 6 mo to control local tumor overgrowth, and ELT was used to treat tumor growth into stent. The survival time of the patients was 26 mo and 32 mo respectively. Because the number of clinical cases was limited, further investigation is needed to elucidate whether secondary therapy after stent insertion can improve the survival time of such patients.

Although placement of metallic stents could lead to some complications[2,17], such as chest pain, bleeding, perforation, fistula, restricture, and approximately 0.5-2% of patients died as a direct result of placement of metallic stents, but most patients had a long-term (1-82 wk, mean 53 wk) palliation[13]. It is thus concluded that metallic stent placement is a simple, quick, safe and efficient method to palliate esophageal carcinoma obstruction.

Co-first-authors: Hai-Shan Yang and Lin-Bo Zhang

Co-correspondents: Tian-Wei Wang

Edited by Wang XL Proofread by Zhu LH

| 1. | Boyce HW. Stents for palliation of dysphagia due to esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1345-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Baron TH. Expandable metal stents for the treatment of cancerous obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1681-1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gevers AM, Macken E, Hiele M, Rutgeerts P. A comparison of laser therapy, plastic stents, and expandable metal stents for palliation of malignant dysphagia in patients without a fistula. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:383-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bartelsman JF, Bruno MJ, Jensema AJ, Haringsma J, Reeders JW, Tytgat GN. Palliation of patients with esophagogastric neoplasms by insertion of a covered expandable modified Gianturco-Z endoprosthesis: experiences in 153 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sarper A, Oz N, Cihangir C, Demircan A, Isin E. The efficacy of self-expanding metal stents for palliation of malignant esophageal strictures and fistulas. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:794-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Siersema PD, Schrauwen SL, van Blankenstein M, Steyerberg EW, van der Gaast A, Tilanus HW, Dees J. Self-expanding metal stents for complicated and recurrent esophagogastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:579-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Laasch HU, Marriott A, Wilbraham L, Tunnah S, England RE, Martin DF. Effectiveness of open versus antireflux stents for palliation of distal esophageal carcinoma and prevention of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. Radiology. 2002;225:359-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vakil N, Morris AI, Marcon N, Segalin A, Peracchia A, Bethge N, Zuccaro G, Bosco JJ, Jones WF. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of covered expandable metal stents in the palliation of malignant esophageal obstruction at the gastroesophageal junction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1791-1796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Macdonald S, Edwards RD, Moss JG. Patient tolerance of cervical esophageal metallic stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:891-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cwikiel W, Tranberg KG, Cwikiel M, Lillo-Gil R. Malignant dysphagia: palliation with esophageal stents--long-term results in 100 patients. Radiology. 1998;207:513-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sihvo EI, Pentikäinen T, Luostarinen ME, Rämö OJ, Salo JA. Inoperable adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction: a comparative clinical study of laser coagulation versus self-expanding metallic stents with special reference to cost analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:711-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dallal HJ, Smith GD, Grieve DC, Ghosh S, Penman ID, Palmer KR. A randomized trial of thermal ablative therapy versus expandable metal stents in the palliative treatment of patients with esophageal carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:549-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lam YH, Chan A, Lau J, Lee D, Ng E, Wong S, Chung S. Self-expandable metal stents for malignant dysphagia. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:668-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Maier A, Pinter H, Friehs GB, Renner H, Smolle-Jüttner FM. Self-expandable coated stent after intraluminal treatment of esophageal cancer: a risky procedure? Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:781-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Muto M, Ohtsu A, Miyata Y, Shioyama Y, Boku N, Yoshida S. Self-expandable metallic stents for patients with recurrent esophageal carcinoma after failure of primary chemoradiotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:270-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kennedy C, Steger A. Fatal hemorrhage in stented esophageal carcinoma: tumor necrosis of the aorta. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2001;24:443-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Golder M, Tekkis PP, Kennedy C, Lath S, Toye R, Steger AC. Chest pain following oesophageal stenting for malignant dysphagia. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:202-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |