Published online Jan 21, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.315

Revised: February 8, 2004

Accepted: April 7, 2004

Published online: January 21, 2005

AIM: To investigate the prevalence of colorectal cancer in geriatric patients undergoing endoscopy and to analyze their outcome.

METHODS: All consecutive patients older than 80 years who underwent lower gastrointestinal endoscopy between January 1995 and December 2002 at our institution were included. Patients with endoscopic diagnosis of colorectal cancer were evaluated with respect to indication, localization and stage of cancer, therapeutic consequences, and survival.

RESULTS: Colorectal cancer was diagnosed in 88 patients (6% of all endoscopies, 55 women and 33 men, mean age 85.2 years). Frequent indications were lower gastrointestinal bleeding (25%), anemia (24%) or sonographic suspicion of tumor (10%). Localization of cancer was predominantly the sigmoid colon (27%), the rectum (26%), and the ascending colon (20%). Stage Dukes A was rare (1%), but Dukes D was diagnosed in 22% of cases. Curative surgery was performed in 54 patients (61.4%), in the remaining 34 patients (38.6%) surgical treatment was not feasible due to malnutrition and asthenia or cardiopulmonary comorbidity (15 patients), distant metastases (11 patients) or refusal of operation (8 patients). Patients undergoing surgery had a very low in-hospital mortality rate (2%). Operated patients had a one-year and three-year survival rate of 88% and 49%, and the survival rates for non-operated patients amounted to 46% and 13% respectively.

CONCLUSION: Nearly two-thirds of 88 geriatric patients with endoscopic diagnosis of colorectal cancer underwent successful surgery at a very low perioperative mortality rate, resulting in significantly higher survival rates. Hence, the clinical relevance of lower gastrointestinal endoscopy and oncologic surgery in geriatric patients is demonstrated.

- Citation: Kirchgatterer A, Steiner P, Hubner D, Fritz E, Aschl G, Preisinger J, Hinterreiter M, Stadler B, Knoflach P. Colorectal cancer in geriatric patients: Endoscopic diagnosis and surgical treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(3): 315-318

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i3/315.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.315

The World Health Report 2003 highlighted the accelerated global population aging, as the number of people aged 60 years or older would double in the next 20 years[1]. Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, accounting for nearly 60000 deaths each year[2]. After the age of 50 the incidence of colorectal cancer accelerates rapidly. In fact, age is the greatest single risk factor for colorectal cancer. Age-specific incidences in patients older than 80 years approximate 465/100000 inhabitants in men and 365/100000 in women[3]. Surgery for colorectal cancer is among the most common major operations performed on elderly patients, so the disease is consumptive of time and resources[4]. Based on census projections the annual number of colon cancer-related admissions in the United States would increase from 192000 in 1992 to 448000 in 2050 in the population over 60 years[5].

The diagnosis of colorectal cancer in a patient older than 80 years usually represents a problematic situation, as other major illnesses are present frequently. It therefore seems prudent to weigh the consequences of a potential diagnosis of colorectal cancer prior to planned endoscopy. However, colorectal surgery should not be withheld from the older patient based on age alone. In this new century, general surgeons have also become geriatric surgeons[6], and it seems possible to achieve favorable outcomes for selected elderly patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer, even in the oldest category, as shown by a recent meta-analysis[7].

Here, this observational study of daily clinical practice evaluated the frequency of colorectal cancer in symptomatic geriatric patients undergoing colonoscopy at our endoscopy unit over a period of 8 years. The benefits of curative surgery as well as the rarely reported course of non-operated patients were delineated.

The study involved all consecutive patients older than 80 years who underwent lower gastrointestinal endoscopy between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2002 at our department, which was responsible for all ambulatory and inpatient endoscopic examinations at the General Hospital Wels, a large referral hospital with 1 060 inpatients. In this setting of daily clinical practice no patient was excluded.

By means of a prospective database all endoscopic examinations leading to diagnosis of colorectal cancer were evaluated. The medical records of the patients were investigated to get additional information if needed. The following parameters were analyzed: indication of endoscopic examination, frequency of colorectal cancer, localization of colorectal cancer, stage of disease, therapeutic consequences, postoperative morbidity and mortality, and long-term survival. To calculate the survival time exactly all available surveillance data was collected and the general practitioners of the patients were contacted by phone in January 2003.

Colonic preparation was performed with a Senna laxative between January 1995 and December 1998. From January 1999 until now all patients were prepared with polyethylene glycol. Patients scheduled for sigmoidoscopy were prepared by means of an enema. From January 1995 until September 2001 all examinations were performed using standard Olympus video endoscopes. From October 2001 until now Olympus video endoscopes were used in one examination room and Fuji video endoscopes in another examination room. The allocation to the examination rooms occurred randomly.

Data is presented as mean±SD. Differences between groups were analysed by Student’s t-test or Chi-square test, as appropriate. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Probability of survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences among time cohorts were compared by the log rank statistic.

A total of 1388 endoscopies of the lower gastrointestinal tract (1175 colonoscopies, 213 sigmoidoscopies) were performed during the study period in patients older than 80 years. At the same time 19915 endoscopies of the lower gastrointestinal tract were performed in patients below or equal to 80 years of age at our unit. The number of endoscopies of the lower gastrointestinal tract in patients older than 80 years was nearly stable from 1995 until 2000 amounting 150 to 170 examinations per year. In the last two years the number of examinations in older patients increased up to 238 in 2002.

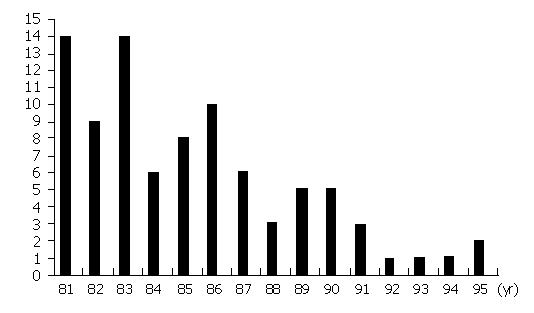

Colorectal cancer was diagnosed in 88 patients (6% of all endoscopies). The patients were 55 women and 33 men, the mean age was 85.2 years, ranging from 81 to 95 years. The distribution of age of these patients is shown in Figure 1. Concomitant major physical illnesses like history of stroke, diabetes, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were observed in 53 patients (60%). Twelve patients suffered from at least two of these comorbidities. Detailed information about concomitant physical illnesses with high impact is shown in Table 1.

| Concomitant physical illnesses | Prevalence | % |

| History of stroke | 16 | 18 |

| Congestive heart failure | 14 | 16 |

| Asthenia and malnutrition | 11 | 13 |

| Diabetes | 10 | 11 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 7 | 8 |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 | 7 |

| Other1 | 5 | 6 |

The most frequent indications to perform the index endoscopy in patients with later diagnosis of colorectal cancer were lower gastrointestinal bleeding in 22 patients (25%), anemia in 21 patients (24%), sonographic suspicion of tumor in 9 patients (10%), constipation in 6 patients (7%) and positive fecal occult blood test in 6 patients (7%). No patient was referred to colonoscopy due to screening purposes.

The localization of cancer was predominantly in the sigmoid colon (24 patients, 27%) and in the rectum (23 patients, 26%). Further anatomical sites were the ascending colon in 18 patients (20%), the transverse colon in 11 patients (13%), the coecum in 10 patients (11%) and the descending colon in 2 patients (2%).

Early stage of colorectal cancer was very rare as stage Dukes A was diagnosed only in 1 patient. Stage Dukes B was common, it was found in 51 patients (58%) and Dukes C was found in 17 patients (19%). Metastatic colorectal carcinoma (Dukes D) was diagnosed in 19 patients (22%).

Surgical treatment with curative intention was performed in 54 patients (61.4%). The most frequent surgical procedure was right-sided hemicolectomy (22 patients), followed by resection of the sigmoid (13 patients) and resection of the rectum (anterior or abdominoperineal resection, 12 patients).

In the remaining 34 patients (38.6%) colonic resection was not feasible due to general bad condition (i.e., combination of asthenia and malnutrition) and/or cardiopulmonary comorbidity (15 patients) or distant metastases (11 patients). Eight patients refused the operation despite detailed information about the malignant disease and the possibility of curative surgical treatment.

Table 2 demonstrates a comparison of the concomitant physical illnesses with high impact in patients with and without surgical treatment. There was no significant difference observed in the two groups regarding cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidity. Diabetes was more common in the operated group and asthenia/malnutrition in the non-operated group, the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001, Chi-square). Furthermore, there was no significant difference regarding age in the two groups, the mean age of patients with and without surgery was 84.9 and 85.8 years respectively (P = 0.19, Student’s t-test).

| Concomitant physical illnesses | Patients with surgery (%) | Patients without surgery (%) | Comparison (Chi-square) |

| History of stroke | 9 (17) | 7 (21) | ns |

| Congestive heart failure | 7 (13) | 7 (21) | ns |

| Asthenia and malnutrition | 1 (2) | 10 (29) | P<0.01 |

| Diabetes | 9 (17) | 1 (3) | P<0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 (6) | 4 (12) | ns |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 (9) | 1 (3) | ns |

| Other1 | 0 (0) | 5 (15) | P<0.01 |

In the group of 54 patients undergoing surgery, the length of postoperative hospital stay ranged from 11 to 42 d, and the patients were discharged after a mean of 18.4 d. The in-hospital mortality rate was very low (2%). Eighteen of these 54 patients (33%) experienced 23 adverse events. There were 14 major adverse events like postoperative delirium (5 patients) or pneumonia (4 patients) and 9 minor events (impaired wound healing). A summary of all postoperative adverse events is shown in Table 3. Life threatening complications like pulmonary embolism or myocardial infarction did not occur during the postoperative recovery. In two patients a repeated laparotomy was necessary (one patient with anastomotic leakage and one patient with bleeding duodenal ulcer and unsuccessful endoscopic intervention). One female patient died unexpectedly on the fourth postoperative day due to acute and massive intracerebral hemorrhage.

| Postoperative complications | Prevalence | % |

| Postoperative delirium | 5 | 9 |

| Pneumonia | 4 | 7 |

| Heart failure | 2 | 4 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 1 | 2 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 |

| Repeated laparatomy | 2 | 4 |

| Impaired wound healing | 9 | 17 |

Palliative interventions were performed in seven patients because of impending mechanical ileus due to obstructing tumor. Four patients underwent palliative surgery as a stoma was created. Their survival time ranged from 1 to 8 mo. Three patients underwent balloon dilatation of rectum or sigmoid colon. In two patients this procedure was successful resulting in a survival time of 4 and 8 mo, respectively. In the third patient a perforation of the sigmoid colon occurred after balloon dilatation. Despite emergency operation and antibiotic therapy this patient died two weeks after the palliative intervention due to purulent peritonitis.

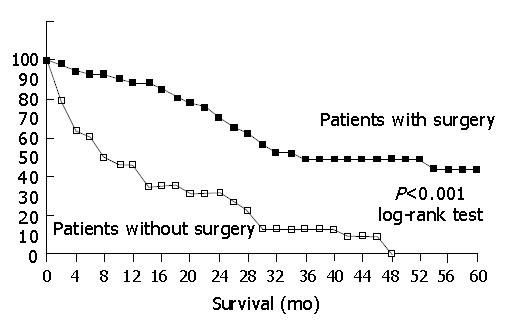

The median survival time of operated patients was 28.2 mo compared to 12.1 mo in patients without surgery; the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001, Student’s t-test). The survival rates of the operated patients after 1, 3 and 5 years amounted to 88%, 49% and 44%, thus being higher than the rates of the non-operated patients with 46%, 13% and 0%, respectively. Figure 2 shows the results of the Kaplan-Meier analysis. The difference of the two groups was statistically significant (P<0.001, log rank test).

The projected ageing of the society influences decision making for endoscopic procedures too. The future needs of this demographic development must be anticipated. Recent publications demonstrated the clinical relevance of screening colonoscopy in the elderly[8], provided no obvious life-limiting comorbidities[9]. However, poor understanding of the screening procedures is one of the greatest problems in early detection of cancer in the aged. We have previously shown that endoscopy of the lower gastrointestinal tract was feasible in a large group of more than 900 geriatric patients with a low complication rate[10]. Other authors reported similar results in smaller groups of elderly patients[11-13]. The actual analysis dealt not only with colonoscopy and endoscopic diagnosis of colorectal cancer in patients older than 80 years but also with the resulting consequences and long-term outcome.

At the moment there existed two important multicentric analyses of colorectal cancer in elderly patients: the report of the Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group[7] and the report of the National Cancer Data Base[14]. Observational studies of a single center are sparse in the field of geriatric oncology. Our analysis of daily clinical practice provided valuable information as all consecutive patients of a large referral hospital were included. During a period of eight years and out of 1 388 endoscopic examinations in patients older than 80 years colorectal cancer was diagnosed in 88 patients. Thus, the study provides important data about the frequency of colorectal cancer when performing endoscopy in geriatric patients and the safety and high prognostic value of surgery for colorectal cancer in these patients. Furthermore, comorbidities with serious clinical impact and survival data of patients without surgical therapy were analyzed.

The most frequent indications to perform the index endoscopy with subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer were as expected: bleeding and anemia constituted nearly fifty percent of all referral diagnoses. Ten percent of the patients were referred to endoscopy due to sonographic suspicion of a tumor. Interestingly, no patient was referred to colonoscopy due to screening.

The observed localizations of colorectal cancers represent an important issue in the ongoing discussion about optimal diagnostic proceedings. Thirty-nine of 88 cancers (44%) were located proximal to the splenic flexure. We are convinced that this fact strongly supports the recommendation to perform colonoscopy instead of sigmoidoscopy, also in symptomatic geriatric patients. Recently, the high impact and cost-effectiveness of colonoscopy in screening for colorectal cancer was demonstrated[15,16].

The rate of surgery in these 88 patients amounted to 61.4%, thus being remarkably lower compared to several other publications. A French study showed that the frequency of curative surgery increased between 1976 and 1990 to a rate of 80% in the last 3-year period[17]. The Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group[7] showed a rate of no operation of 21 % in patients older than 85 years and the National Cancer Data Base[14] reported a rate of no operation of 12.5 % in patients aged 80 years or above. A recent Chinese study reported a rate of curative resection of 71.5% in 165 patients aged 70 or older. Surgical treatment was not possible due to concomitant physical illnesses in several of our patients, and the combination of malnutrition and asthenia was the most important interference with the surgery (10 patients, 11.4%). One might argue that performing colonoscopy in patients older than 80 years with malnutrition and asthenia often results in questionable clinical situations with the diagnosis of malignant disease without any reliable chance of surgery. It seems likely that unrestricted referral practices in our hospital leading to endoscopy in multimorbid patients partially explain our low rate of curative surgery. However, we also observed a remarkable rate of refusal of surgical treatment (8 of 88 patients, 9%). We assume that this phenomenon is not limited to our single center and that refusal of therapy represents an important fact in geriatric patients although not reported in detail in other studies.

In comparison to former publications, which reported postoperative mortality rates between 6% and 16% in geriatric patients[18-24], we observed a striking lower rate in our patients (2%). This low frequency represents the concerted success of both optimal surgical technique and perioperative management by anesthesiologists. On the other hand, a further explanation could be careful preoperative decision making not to operate on patients in whom unfavorable outcome is anticipated. We think that surgical treatment of more than 80% of geriatric patients with colorectal cancer is likely to be associated with higher postoperative mortality rates and there exists a direct relationship between the rate of surgery and the rate of postoperative complications in this age group. In our opinion, Violi et al[22] stated correctly that the rate of patients excluded from a curative program because of general contraindications was of great importance when evaluating surgical results in the aged.

A study dealing with concomitant major physical illnesses demonstrated that the number of comorbid conditions was significant in predicting early mortality in a model including age, gender and disease stage[25]. Our results of an exceptional low in-hospital mortality rate (after surgical treatment of only two-thirds of the patients) opened the discussion that preoperative assessment possibly caused the selection of fitter patients. This was true regarding malnutrition and asthenia, as patients who were not operated significantly more often suffered from these two conditions. However, cardiopulmonary diseases were not different in the two groups and diabetes was even more common in patients with subsequent surgery.

The overall survival rate of patients with surgical treatment after 1, 3 and 5 years was 88%, 49% and 44%, thus being comparable to other publications[7,17,26]. We believe that it is necessary to bring these survival rates in relation to statistical data regarding life-expectancy in octogenarians. The average number of years of life remaining in persons between 80 and 85 years was 6.8 in men and 8.7 in women[27].

The survival rate of non-operated, elderly patients with colorectal cancer was rarely reported in the literature. Nevertheless, non-operated patients asked their physicians about their life expectancy. Our analysis showed that the survival rate of these patients was low, but not hopeless in individual patients. However, the 3-year survival rate of 13% indicates that surgical treatment of colorectal cancer should be performed whenever possible.

In the postoperative period, patients were discharged after a mean of 18.4 d, and in 17 patients important complications were observed like impaired wound healing (17%), postoperative delirium (9%) and pneumonia (7%). However, 37 of 54 patients had an uneventful course which underscores the feasibility of colorectal surgery in the elderly.

In conclusion, clinicians should be familiar with ethical dilemmas and difficult decision making when caring for elderly patients[28]. The current study analyzed the clinical course of 88 consecutive geriatric patients following endoscopic diagnosis of colorectal cancer. We disclosed a frequency of surgical treatment lower than previously published (due to malnutrition, distant metastasis, refusal of operation), but excellent postoperative results with an in-hospital mortality of only 2% and a 1-year survival rate of 88%. Hence, clinical relevance of lower gastrointestinal endoscopy and oncologic surgery in geriatric patients is demonstrated in a setting of daily clinical practice.

Edited by Wang XL Proofread by Chen WW

| 1. | World Health Organisation. The World Health Report 2003. Available from: http: //www.who.int/whr/2003/chapter1. |

| 2. | Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:5-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2651] [Cited by in RCA: 2514] [Article Influence: 114.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Eddy DM. Screening for colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:373-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alley PG. Surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients. Lancet. 2000;356:956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Seifeldin R, Hantsch JJ. The economic burden associated with colon cancer in the United States. Clin Ther. 1999;21:1370-1379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pofahl WE, Pories WJ. Current status and future directions of geriatric general surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:S351-S354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: a systematic review. Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356:968-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 441] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wan J, Zhang ZQ, Zhu C, Wang MW, Zhao DH, Fu YH, Zhang JP, Wang YH, Wu BY. Colonoscopic screening and follow-up for colorectal cancer in the elderly. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:267-269. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Stevens T, Burke CA. Colonoscopy screening in the elderly: when to stop? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1881-1885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kirchgatterer A, Hubner D, Aschl G, Hinterreiter M, Stadler B, Knoflach P. Colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy in patients aged eighty years or older. Z Gastroenterol. 2002;40:951-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Clarke GA, Jacobson BC, Hammett RJ, Carr-Locke DL. The indications, utilization and safety of gastrointestinal endoscopy in an extremely elderly patient cohort. Endoscopy. 2001;33:580-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sardinha TC, Nogueras JJ, Ehrenpreis ED, Zeitman D, Estevez V, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Colonoscopy in octogenarians: a review of 428 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1999;14:172-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ure T, Dehghan K, Vernava AM, Longo WE, Andrus CA, Daniel GL. Colonoscopy in the elderly. Low risk, high yield. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:505-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jessup JM, McGinnis LS, Steele GD, Menck HR, Winchester DP. The National Cancer Data Base. Report on colon cancer. Cancer. 1996;78:918-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Inadomi JM, Sonnenberg A. The impact of colorectal cancer screening on life expectancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:517-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sonnenberg A, Delcò F, Inadomi JM. Cost-effectiveness of colonoscopy in screening for colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:573-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Arveux I, Boutron MC, El Mrini T, Arveux P, Liabeuf A, Pfitzenmeyer P, Faivre J. Colon cancer in the elderly: evidence for major improvements in health care and survival. Br J Cancer. 1997;76:963-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fielding LP, Phillips RK, Hittinger R. Factors influencing mortality after curative resection for large bowel cancer in elderly patients. Lancet. 1989;1:595-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Arnaud JP, Schloegel M, Ollier JC, Adloff M. Colorectal cancer in patients over 80 years of age. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:896-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fabre JM, Rouanet P, Ele N, Fagot H, Guillon F, Deixonne B, Balmes M, Domergue J, Baumel H. Colorectal carcinoma in patients aged 75 years and more: factors influencing short and long-term operative mortality. Int Surg. 1993;78:200-203. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Mulcahy HE, Patchett SE, Daly L, O'Donoghue DP. Prognosis of elderly patients with large bowel cancer. Br J Surg. 1994;81:736-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Violi V, Pietra N, Grattarola M, Sarli L, Choua O, Roncoroni L, Peracchia A. Curative surgery for colorectal cancer: long-term results and life expectancy in the elderly. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:291-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kruschewski M, Germer CT, Rieger H, Buhr HJ. Radical resection of colorectal carcinoma in the oldest old. Chirurg. 2002;73:241-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Smith JJ, Lee J, Burke C, Contractor KB, Dawson PM. Major colorectal cancer resection should not be denied to the elderly. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:661-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, Havlik RJ, Long S, Edwards BK, Yates JW. Comorbidity and age as predictors of risk for early mortality of male and female colon carcinoma patients: a population-based study. Cancer. 1998;82:2123-2134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Marrelli D, Roviello F, De Stefano A, Vuolo G, Brandi C, Lottini M, Pinto E. Surgical treatment of gastrointestinal carcinomas in octogenarians: risk factors for complications and long-term outcome. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:371-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yancik R, Ries LA. Cancer in older persons. Magnitude of the problem--how do we apply what we know? Cancer. 1994;74:1995-2003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mueller PS, Hook CC, Fleming KC. Ethical issues in geriatrics: a guide for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:554-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |