Published online Jul 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i28.4447

Revised: November 1, 2004

Accepted: November 4, 2004

Published online: July 28, 2005

Two cases of acute pancreatitis with leptospirosis are reported in this article. Case 1: A 68-year-old woman, presented initially with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice. She was in poor general condition, and had acute abdominal signs and symptoms on physical examination. Emergency laparotomy was performed, acute pancreatitis and leptospirosis were diagnosed on the basis of surgical findings and serological tests. The patient died on postoperative d 6. Case 2: A 62-year-old man, presented with fever, jaundice, nausea, vomiting, and malaise. Acute pancreatitis associated with leptospirosis was diagnosed, according to abdominal CT scanning and serological tests. The patient recovered fully with antibiotic treatment and nutritional support within 19 d.

- Citation: Kaya E, Dervisoglu A, Eroglu C, Polat C, Sunbul M, Ozkan K. Acute pancreatitis caused by leptospirosis: Report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(28): 4447-4449

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i28/4447.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i28.4447

Leptospirosis is a spirochetal bacterial infection and causes clinical illness in animals and humans. This zoonosis is common in some other parts of the world but rather rare in Turkey[1,2]. This disease is predominantly seen in farmers, trappers, veterinarians, and rice-field workers. Leptospirosis mainly affects liver and kidney. Rarely, other organs such as lung, heart, gallbladder, brain, and ophthalmic tissues are involved, mainly due to vasculitis[3,4]. Hyperamylasemia can be present in leptospirosis infection due to renal impairment[5-7]. Therefore, the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is controversial in this disease.

Pancreatitis is a rare complication of leptospirosis and only a few cases have been reported in literature[1,5,8,9]. We report two cases here.

A 68-year-old woman was referred to Ondokuz Mayis University hospital for abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice with 1-d history. She had no history of contact with jaundiced persons, blood transfusions and drug abuse. She was operated on 3 years ago for hip fracture and occasionally she took some analgesics. On physical examination, she was in poor general condition with dehydration and her scleras were icteric. Her pulse rate was 120/min, blood pressure 14.6/10.6 kPa and she was tachypneic. Urine output was normal. There was a marked tenderness in her whole abdomen with guarding and rebound tenderness. No other abnormalities were noted. Laboratory investigations on admission revealed Hb: 13 g/dL, Htc: 39.7, WBC: 9 000/mm3, platelet count: 120 000/mm3 (n: 150×103-300×103), BUN: 60 mg/dL (n: 5-24), creatinine (Cr): 2.7 mg/dL (n: 0.4-1.4), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): 2 321 U/L (n: 95-500), total/direct bilirubin: 6.5/4.7 mg/dL, Ca: 7.8 mg/dL (8-10), amylase: 630 U/L (28-100), lipase: 642 U/L (n: 0-190), aspartate transaminase (AST): 2 500 U/L (n: 8-46), alanine transaminase (ALT): 1 900 U/L (n: 7-46), serum C-reactive protein (CRP): 192 mg/L (n: 0-5), PaO2: 7.71 kPa, base excess (BE): -5 mmol/L, with negative viral hepatitis markers. The Ranson score was 8. Abdominal ultrasonographic examination revealed acute calculus cholecystitis and abdominal fluid collection. Biliary dilatation was not observed in ultrasonographic examination.

The patient was operated on with the diagnosis of surgical acute abdomen. On exploration, 500 mL sero-hemorrhagic fluid was found in the abdominal cavity, and gallbladder and pancreas were found to be markedly edematous. Areas of fatty necrosis were seen on peripancreatic tissues. Cholecystectomy and common bile duct exploration were done. Pre-operative cholangiogram was normal. Histo-pathologic diagnosis of the gallbladder was acute cholecystitis. Leptospires were seen in blood, intra-abdominal fluid and bile on dark-field microscopy. Leptospira microagglutination test was positive (at 1:100 Leptospira samaranga Patoc I). Penicillin G, 3 million units four times per day was given to the patient intravenously. Total parenteral nutrition was also started for artificial nutrition. The patient recovered after operation and oral intake was started on postoperative d 5. Although liver function tests and laboratory values returned to normal within 5 d, others included Hb: 11 g/dL, platelet count: 170 000/mm3, BUN: 43 mg/dL, Cr: 0.8 mg/dL, total/direct bilirubin: 1.9/1.56 mg/dL, AST: 47 U/L, ALT: 168 U/L. Six days after the operation the patient died due to a suddenly developed cardiopulmonary arrest.

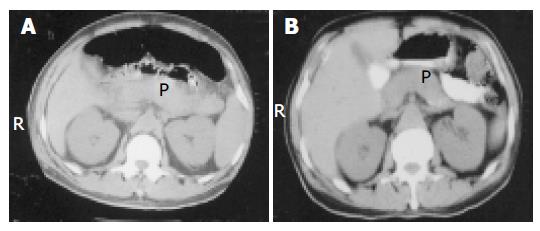

A 62-year-old man was admitted to Ondokuz Mayis University hospital with fever, marked jaundice, nausea, and vomiting. The patient had also 2 wk history of malaise, fever, and dizziness before hospital admission. On examination, the patient was icteric and there was conjunctival hyperemia. His temperature was 39 °C and blood pressure was 19.9/11.9 kPa. Urine output was 30 mL/h. The remainder of the physical examination was normal. Laboratory investigations on admission showed Hb: 8.6 g/dL, Htc: 27.8, WBC: 23 000/mm3, platelet count: 53 000/mm3, glucose 140 mg/dL, total/direct bilirubin: 48/44 mg/dL, AST: 70 U/L, ALT: 85 U/L, alkaline phosphatase: 516 U/L (n: 95-280), g-glutamic transpeptidase: 104 U/L (n: 7-49), BUN: 120 mg/dL, Cr: 17 mg/dL, LDH: 1 638 U/L, total protein 4.8 g/dL (n: 6-8.5), albumin: 2.2 g/dL (n: 3.5-5), amylase 980 U/L, pancreatic amylase: 830 U/L (n: 13-53), lipase: 797 U/L, Ca: 7.5 mg/dL, CRP: 68, negative viral hepatitis markers. The Ranson score was 6. Leptospira microagglutination test was positive (at 1/800, L icterohemorrhagica). Leptospires were seen in blood on dark-field microscopy. Abdominal CT examination revealed bilateral pleural effusion, intra-abdominal minimal fluid collection, pancreatic edema and peripancreatic tissues heterogeneity (Figure 1A).

A diagnosis of leptospirosis with acute pancreatitis was made. The patient had renal failure in acute non-oliguric form. Hemodialysis was performed at the beginning of the treatment. Intravenous fluid resuscitation and ampicillin-sulbactam treatment were given. Nasojejunal feeding tube was inserted endoscopically for adequate caloric intake. Four days after the treatment, body temperature decreased to 37.5 °C, amylase levels decreased to normal value 150 U/L and platelet count increased to 150 000/mm3. Bilirubin levels, liver function tests, and creatinine level slowly returned to normal within 2 wk (laboratory tests at the discharge time revealed WBC: 9 000/mm3, Hb: 90 g/L, total/direct bilirubin: 2/1.8 mg/dL, BUN: 30 mg/dL, Cr: 1.2 mg/dL, AST: 24 U/L, ALT: 45 U/L, LDH: 380 U/L). Oral intake was started on d 19 of admission and the patient was discharged. Abdominal CT findings at the discharge time revealed minimal edema in the pancreas (Figure 1B). The patient was examined 2 mo later and he was in a completely healthy condition.

Leptospirosis is a spirochetal zoonosis that causes clinical illness in humans as well as in animals. The source of infection in humans is usually either direct or indirect contact with the urine of infected animals. These bacteria infect humans by entering through abraded skin, mucous membrane, conjunctivae. Direct transmission between humans is rare[3,4]. Leptospirosis is a common disease in rice-field workers due to prevalence of wild rats[4,8]. Both of our patients were from rural area of the middle Black Sea region of Turkey and have worked in rice fields. Rice field with stagnant water and humid condition is an ideal environment for leptospira.

Leptospirosis is characterized by the development of vasculitis, endothelial damage, and inflammatory infiltration. This disease mostly affects tissues of the liver and kidney. Other tissues such as the pancreas can be affected due to vasculitis[4].

This disease occurs as two clinically recognizable syndromes: the anicteric leptospirosis (80-90% of all cases) and the remainder icteric leptospirosis[3,4]. Icteric leptospirosis is known as Weil's disease, which is characterized by hemorrhage, renal failure, and jaundice. Icteric leptospirosis is a much more severe disease than anicteric form. The clinical course is often rapidly progressing. Our cases seemed to be icteric leptospirosis. Serological tests confirmed on blood samples as L icterohemorrhagica and L samaranga Patoc. First of these is responsible for icteric form of the disease. L samaranga Patoc sero-type is not the cause of Weil's disease but cross-reaction is possible between the serotypes of leptospirosis.

Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in leptospirosis, occurring in 40-85% of this disease. But the exact reason for thrombocytopenia is unknown. Vasculitis, increased peripheral destruction and decreased thrombocyte production have been considered as potential causes of thromboc-ytopenia[4,10]. Thrombocytopenia was also present in the two cases reported here which were remedied by our treatment.

Oliguric and non-oliguric acute renal failure may be observed in icteric leptospirosis[7], as also seen in our cases. It was reported that oliguria was a significant predictor of death in leptospirosis[4]. Urine output was normal in case 1 but case 2 was oliguric. Renal insult was treated with intravenous fluid replacement and other supportive treatment including antibiotic and hemodialysis in case 2.

Jaundice occurring in leptospirosis is not commonly associated with hepatocellular necrosis and impaired liver function. There are moderate rises in transaminase levels, and minor elevation of alkaline phosphatase level usually occurs[3,4]. Hepatic dysfunction occurs but resolves, and it is rarely the cause of death. The serum bilirubin level is usually <20 mg/dL but can be as high as 60-80 mg/dL. The bilirubin level of case 2 was close to this value (48 mg/dL). In case 1, transaminase levels were very high (more than 2 000 U/dL). The elevation of transaminases that is more than threefold of the normal value is not usual. Some sporadic cases with very high transaminase level were reported in the medical literature[11]. Furthermore, hepatocyte degener-ation and liver cell necrosis have been reported in biliary pancreatitis[12,13]. So, elevated transaminases levels as high as that in case I may be seen in leptospirotic hepatitis. Pancreatic and bile tree involvement can be additional factors for liver cell necrosis. Acute cholecystitis was pathologically confirmed and leptospires were seen in bile in case 1. Therefore, we believe that hepatobiliary and pancreatic involvement could be possible in this case.

For the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, a simultaneous determination of both amylase and lipase is recommended for the evaluation of patient with abdominal pain. The serum amylase test is available in nearly all laboratories and at all hours. Elevation of lipase level with serum amylase is important for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Elevation of pancreatic izoamylase level also supports the diagnosis[14]. Hypera-mylasemia also can be seen in leptospirosis due to renal function alterations or other unknown reasons[5,6]. The serum amylase and lipase levels were elevated more than threefold of normal level in both cases. Pancreatic izoamylase level was also elevated at diagnostic level in case 2.

CT scan is a gold standard in diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, as shown by many authors who use it. This diagnostic test has 100% specificity and over 90% sensitivity for this disease[15-17]. We also routinely use CT for both diagnosis and follow-up of the treatment as in case 2. Because abdominal CT scan was not available in the emergency condition in our hospital, we could not use it in case 1. However, the pathologic findings of acute pancreatitis were clearly observed at laparotomy in this case. So, there is no diagnostic dilemma for both of two presented cases.

The treatment of acute pancreatitis in leptospirosis includes antibiotic treatment against leptospira and supportive treatments for acute pancreatitis (including intravenous fluid resuscitation and nutrition). We preferred the nutritional support (parenterally or enterally but mostly enterally) in severe acute pancreatitis. This regime was successful in case 2. Case 1 also completely recovered after d 5 and she could feed orally. We believe that the reason of mortality was pulmonary embolism in case 1.

In conclusion, pancreatitis may be seen in leptospirosis infection. Leptospirosis should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of hyperamylasemia, pancreatitis, and obstructive jaundice in endemic areas. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment is essential for life saving.

Science Editor Zhu LH Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Leblebicioglu H, Sencan I, Sünbül M, Altintop L, Günaydin M. Weil's disease: report of 12 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:637-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Casella G, Scatena LF. Mild pancreatitis in leptospirosis infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1843-1844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Farr RW. Leptospirosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1-6; quiz 7-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:296-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1940] [Cited by in RCA: 1837] [Article Influence: 76.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Edwards CN, Evarard CO. Hyperamylasemia and pancreatitis in leptospirosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1665-1668. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kameya S, Hayakawa T, Kameya A, Watanabe T. Hyperamylasemia in patients at an intensive care unit. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:438-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cengiz K, Sahan C, Sünbül M, Leblebicioğlu H, Cüner E. Acute renal failure in leptospirosis in the black-sea region in Turkey. Int Urol Nephrol. 2002;33:133-136. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sunbul M, Esen S, Leblebicioglu H, Hokelek M, Pekbay A, Eroglu C. Rattus norvegicus acting as reservoir of leptospira interrogans in the Middle Black Sea region of Turkey, as evidenced by PCR and presence of serum antibodies to Leptospira strain. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:896-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | O'Brien MM, Vincent JM, Person DA, Cook BA. Leptospirosis and pancreatitis: a report of ten cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:436-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Turgut M, Sünbül M, Bayirli D, Bilge A, Leblebicioğlu H, Haznedaroğlu I. Thrombocytopenia complicating the clinical course of leptospiral infection. J Int Med Res. 2002;30:535-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kuntz E, Kuntz HD. Hepatology. 1 st ed. Hiedelberg: Springer Verlag, Berlin 2000; 425. |

| 12. | Tenner S, Dubner H, Steinberg W. Predicting gallstone pancreatitis with laboratory parameters: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1863-1866. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Isogai M, Yamaguchi A, Hori A, Nakano S. Hepatic histopathological changes in biliary pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:449-454. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Frank B, Gottlieb K. Amylase normal, lipase elevated: is it pancreatitis? A case series and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:463-469. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Clavien PA, Hauser H, Meyer P, Rohner A. Value of contrast-enhanced computerized tomography in the early diagnosis and prognosis of acute pancreatitis. A prospective study of 202 patients. Am J Surg. 1988;155:457-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moossa AR. Current concepts. Diagnostic tests and procedures in acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:639-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lott JA. The value of clinical laboratory studies in acute pancreatitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115:325-326. [PubMed] |