Published online Jul 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i28.4344

Revised: January 7, 2005

Accepted: January 13, 2005

Published online: July 28, 2005

AIM: We set to determine factors that determine clinical severity after the development of resistance.

METHODS: Thirty-five Asian patients with genotypic lamivudine resistance were analyzed in three groups: 13/35 (37%) were non-cirrhotics with normal pre-treatment ALT (Group IA), 12/35 (34%) were non-cirrhotics with elevated pre-treatment ALT (Group IB), and 10/35 (29%) were cirrhotics (Group II). Patients were followed for a median of 98 wk (range 26-220) after the emergence of genotypic resistance.

RESULTS: Group IA patients tended to retain normal ALT. Group IB patients showed initial improvement of ALT with lamivudine but 9/12 patients (75%) developed abnormal ALT subsequently. On follow-up however, this persisted in only 33%. Group II patients also showed improvement while on treatment, but they deteriorated with the emergence of resistance with 30% death from decompensated liver disease. Pretreatment ALT levels and CPT score (in the cirrhotic group) were predictive of clinical resistance and correlated with peak ALT levels and CPT score.

CONCLUSION: The phenotype of lamivudine-resistant HBV correlated with the pretreatment phenotype. The clinical course was generally benign in non-cirrhotics. However, cirrhotics had a high risk of progression and death (30%) with the development of lamivudine resistance.

- Citation: Dan YY, Wai CT, Lee YM, Sutedja DS, Seet BL, Lim SG. Outcome of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus is generally benign except in cirrhotics. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(28): 4344-4350

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i28/4344.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i28.4344

Treatment of CHB was revolutionized by the introduction of orally administered antiviral agents. Lamivudine, a nucleoside analog and the first orally available antiviral agent for CHB, had demonstrated significant results in clinical trials, with universal suppression of HBV DNA level by 3 logs, 55% improvement in histological necroinflammatory score, normalization of ALT in the majority of patients after 1 year of treatment[1,2]. Even among patients with decompen-sated hepatitis B cirrhosis, there was clinical improvement[3], thus enabling some of them to be taken off liver transplant waiting lists.

However, drug resistance with lamivudine occurs with prolonged usage, rising from 14-24% at the end of first year, to 57% by the end of year 3[4,5]. Resistance occurred primarily as a result of mutations in the YMDD motif of the polymerase gene although subsequently, mutations at other sites have been reported[6]. Initial reports suggested that lamivudine-resistant HBV virus may be less virulent and replication-defective, as the ALT and HBV DNA levels caused by these mutant viruses were lower than the pretreatment values[7]. However, subsequent reports of decompensation, acute exacerbations, and deaths from such mutant viruses suggested otherwise[8,9]. This has given rise to the suggestion of limiting lamivudine therapy to 12 mo duration in order to avoid the development of these mutants[10].

Lamivudine resistance can be divided into genotypic and clinical phenotypic resistance. Genotypic resistance refers to the presence of a lamivudine-resistant strain such as the YMDD mutants, which in itself may not lead to any clinical sequela, since such strains have been detected in patients who have not had prior exposure to lamivudine[11]. Clinical phenotypic resistance refers to the presence of genotypic resistance with the subsequent development of clinical deterioration, defined as elevation of transaminases and/or deterioration of liver histology and liver function. Factors that predict the development of genotypic resistance[5,12] had been evaluated in many studies, which included pretreatment HBV DNA level, ALT level, body mass index, adw serotype, and core promoter mutations[13-15]. However, these studies did not address the more important question of which factor(s) actually lead to clinical resistance.

Hence, we set to examine variables that determined the clinical phenotypes after the development of genotypic lamivudine resistance.

From January 1996 to April 2003, we prospectively followed all patients started on lamivudine 100 or 150 mg daily monotherapy for clinical indications, or who had completed trials of lamivudine monotherapy, at 3 monthly intervals. These included patients who were recruited from the Asian Multicentre Lamivudine Trial and its subsequent rollover follow-up study NUCB3018[1,4,16], which also included patients with normal pre-treatment ALT levels. Patients were also given lamivudine if it was clinically indicated, such as persistently abnormal ALT levels (greater than twice upper limit of normal for at least 3 mo duration), decompensated liver disease (development of variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy), or were on the liver transplant waiting list. All patients had detectable HBV DNA by a non-PCR based assay prior to initiation of therapy. Lamivudine was prescribed for at least a year and was continued even when genotypic resistance developed. During the duration of the study, none of the patients were given adefovir dipivoxil as a rescue therapy as it was not yet available in Singapore. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National University Hospital, Singapore.

Patients who tested positive for anti-HCV, anti-HDV, and HIV, had significant history of alcohol intake (defined as more than seven drinks per week), or were non-compliant with lamivudine were excluded from the study. Patients who developed resistance after liver transplants were also excluded.

Prior to March 2000, the Abbott HBV DNA assay (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA) was used for HBV DNA viral load quantification. After March 2000, this assay was substituted to a branched-chain assay (Chiron QuantiplexTM, Chiron Corp). Results of the Abbott HBV DNA assay were converted using the Multimeasurement Method[17].

Eligible patients were classified into three distinct phenotypes according to their baseline characteristics. The presence of cirrhosis was determined by liver biopsy or by ultrasonographic features in those with clinical decompensated disease.

Group IA Non-cirrhotic patients with normal baseline ALT level

Group IB Non-cirrhotic patients with abnormal baseline ALT level

Group II Cirrhotic patients

Genotypic resistance was defined as reappearance of at least two consecutive detectable HBV DNA levels after a period of undetectable level whilst on continuous lamivudine therapy for more than 6 mo.

Confirmation of genotypic resistance was performed by comparison of results from direct sequencing of the HBV polymerase of the HBV DNA samples before starting lamivudine, and after development of resistance. DNA was extracted and direct sequencing was performed at a 750 bp region between nt 253 and 1 006 of the HBV genome using the two primers:

Forward primer: 5’-GAC TCG TGG TGG ACT TCT CTC AA- 3’.

Reverse primer: 5’-CCC ACA ATT CTT TGA CAT ACT TTC C-3’. The forward and reverse sequences were aligned using the Seqman program (DNAstar). This segment has been known to contain all the mutations known to confer lamivudine resistance. New mutations emerging after treatment of lamivudine were determined for their resistance conferring properties from previously published data and categorized using the new nomenclature[6,18].

All patients were followed for a minimum of 6 mo after the emergence of genotypic resistance and for as long as the patients were continued on lamivudine. Serial analysis of ALT, bilirubin, prothrombin time, HBeAg, anti HBe and HBV DNA level by Chiron QuantiplexTM, at 3 monthly intervals were done. Serial Child-Pugh Turcot (CPT) scores were also calculated. No serial liver biopsy was performed in our patients.

In the non-cirrhotic group, clinical resistance was defined as abnormal rise in ALT greater than twice upper limit of normal. In the cirrhotic group, clinical resistance was defined as abnormal rise in ALT greater than twice the normal upper limit, or an increase of CPT Score by two points or more.

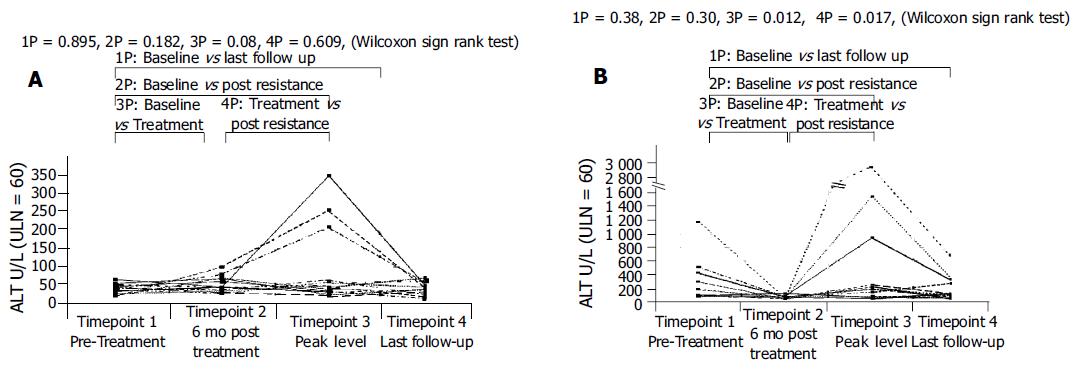

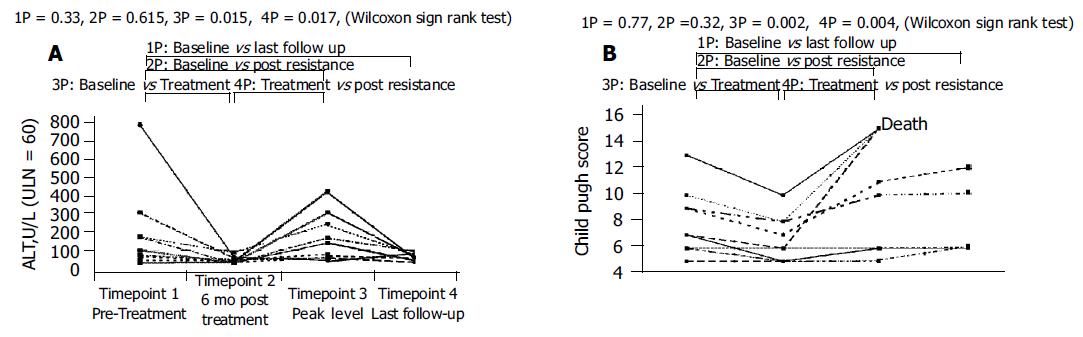

Clinical severity was assessed at four time points: timepoint 1 (baseline or pretreatment), timepoint 2 (6 mo after the commencement of lamivudine therapy), timepoint 3 (peak ALT or CPT levels after the development of genotypic resistance), and timepoint 4 (last ALT or CPT on follow-up).

HBV genotyping was performed using restriction fragment length polymorphism created by Ava2 and Dpn2 action on an amplified segment of the pre-S region as previously described[19].

Changes in ALT level and CPT Score were compared at four timepoints within each group of patients. Statistical analysis was performed by Wilcoxon Matched-Pairs Signed Rank Test to avoid the effect of pooling results from different patients. The relationship of two continuous variables was tested by Spearman r Correlation test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The following parameters: age, sex, baseline ALT, ALT at the point of emergence of resistance, baseline HBV DNA level, peak HBV DNA post genotypic resistance, duration of lamivudine treatment, type of mutation, genotype and HBeAg seroconversion were analyzed by univariate analysis to determine factors associated with phenotypic resistance. Categorical variables and continuous variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t-test, as appropriate. Significant factors from univariate analysis were then analyzed by multivariate analysis by forward logistic regression to determine independent factors associated with phenotypic resistance.

All statistical analysis was performed using computer software, SPSS 10.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

A total of 78 patients were prescribed lamivudine for hepatitis B related indications or had completed a clinical trial of lamivudine therapy at our institution for a minimum of 1 year during the study period. Of these, 35 patients (45%) developed genotypic resistance to lamivudine while on treatment after a median of 143 wk (range 35-212 wk) and were included in this study. Twenty-one (60%) were part of the Asian Lamivudine Trial (NUCB 3009/NUCB3018)[1], of which 11 received uninterrupted lamivudine treatment while 10 were restarted on open label lamivudine after viral breakthrough when they were on placebo. The remainder of the patients was given lamivudine for clinical indications of chronic hepatitis (n = 4, 11%) and cirrhotic liver disease (n = 10, 29%), respectively. One patient was eligible to enter a trial of adefovir/lamivudine (NUCB 20904) treatment for persistent abnormal transaminases at 56 wk after emergence of resistance. Data up to the point of trial entry was used for analysis but data thereafter was censored. No patient received liver transplant after the emergence of resistance. Thus in total, 35 patients were eligible for analysis. There were no missing patients or dropouts from the cohort.

All 35 patients were stratified into three groups (Table 1): 13 patients (37%) were in Group IA (non-cirrhotic patients with normal baseline ALT), 12 (34%) of patients were in Group IB (non-cirrhotic patients with abnormal baseline ALT), and the remainder of the patients (n = 10, 29%) were in Group II (cirrhotic patients). Group IA and B patients were predominantly from the Asian Lamivudine trial and had a median age of 35 years (range: 21-48 years) and 34 years (range 20-45 years), respectively. Patients in Group II were expectedly older with median age of 52 years (range 42-68). There was a preponderance of male patients (M:F = 30:5). With the exception of one Malay patient, all remaining patients were Chinese (97%). Of these 35 patients, genotypic resistance developed at a median of 143 wk after being on lamivudine (range 35-212). Median patients follow-up after genotypic resistance was 102 wk (range 26-220).

| Group IA | Group IB | Group II | All patients | |

| n = 13 (37%) | n = 12 (34%) | n = 10 (29%) | n = 35 (100%) | |

| Median age (range) | 35 (21-48) | 34 (20-45) | 52 (42-68) | 38 (20-68) |

| Male (%) | 9 (69) | 11 (92) | 10 (100) | 30 (86) |

| Chinese ethnicity (%) | 13 (100) | 11 (92) | 10 (100) | 34 (97) |

| Median (range) baseline ALT, U/L | 28 (16-58) | 136 (78-1 124) | 87 (33-761) | 74(16-1 124) |

| Median (range) baseline HBV DNA, Meg/mL | 294 (120–1 680) | 253 (38–616) | 291 (20–786) | 280 (20–1 680) |

| Median baseline CPT score | NA | NA | 7.0 (5-13) | NA |

| Median (range) duration of lamivudine | ||||

| at emergence of genotypic resistance, wk | 160 (35-198) | 110 (42-212) | 62 (36-120) | 143 (35-212) |

| Follow-up after genotypic resistance, wk | 96 (48-220) | 124 (26-208) | 64 (34-102) | 102 (26-220) |

| Number (%) with phenotypic resistance | 3 (23) | 9 (75) | 6 (60) | 18 (51) |

Majority of the patients had either genotypes B or C. Eighteen (51%) were of HBV genotype B while 13 patients (37%) had genotype C. Four (12%) had other genotypes: one was Genotype A, one had a mixture of B/C genotypes, and two were untypable (Table 2).

| Patients with phenotypic resistance n = 18 | Patients without phenotypic resistance n = 17 | P | |

| Median (range) age (yr) | 34 (21-60) | 37(20-68) | 0.95 |

| Male (%) | 17 (94) | 13 (76) | 0.16 |

| Chinese (%) | 17/18 (94) | 17/17 (100) | 0.28 |

| Genotype (B:C:others) | 7B/ 7C/ 2 others | 11B /6C/ 2 others | 0.56 |

| Type of mutation (rtM204I:rtM204V:others) | 12:2:4 | 4:10:3 | 0.074 |

| Median (range) baseline ALT level, U/L | 96 (42-1 124) | 40 (16-143) | 0.018 |

| ALT level at emergence of genotypic resistance, U/L | 48 (22-82) | 36 (24-68) | 0.36 |

| Successful HBeAg seroconversion (%) | 12 | 17.7 | 0.43 |

| Median (range) baseline HBV DNA, Meq/mL | 249 (20-788) | 336 (20-1 680) | 0.17 |

| Median (range) peak HBV DNA after emergence of resistance, pg/mL | 186 (8.8-1 064) | 314 (9-3 920) | 0.33 |

| Median (range) duration of lamivudine at onset of resistance, wk | 88 (35-212) | 124 (36-202) | 0.16 |

| Median (range) duration of follow up after resistance, wk | 124 (52-204) | 102 (26-220) | 0.29 |

| Median (range) baseline CPT Score for cirrhotic patients, n = 10 | (n = 6) 8 (5-13) | (n = 4) 7 (5-9) | 0.038 |

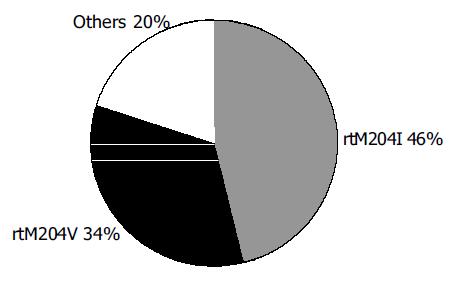

Sixteen of thirty-five patients (46%) were found to have the rtM204I (YIDD) mutation at the YMDD motif, whilst 12/35 (34%) demonstrated the rtM204V (YVDD) mutation and the remainder had at least one acquired mutation that was not present at the baseline and was known to confer resistance against lamivudine. (Figure 1). These included various combinations of mutations at rtA181T, rtL80V/I and rtL187I.

(1) Group IA (non-cirrhotic with normal baseline ALT), n = 13 (Figure 2A).

Only three patients (23%) developed abnormal ALT after the emergence of genotypic resistance at median follow-up of 96 (range: 48-220 wk). The changes in ALT in the group between the four timepoints were non-significant. All three patients normalized their ALT after a median duration of 6 (range: 4-12 wk), one of whom achieved HBeAg seroconversion;

(2) Group IB (non-cirrhotic with abnormal baseline ALT), n = 12 (Figure 2B).

Normalization of ALT levels 6 mo after starting lamivudine was seen in all patients (Wilcoxon signed Rank P = 0.012). However, with the emergence of genotypic resistance, 9 out of 12 patients (75%) developed abnormal ALT (Wilcoxon signed Rank P = 0.017) after median follow-up of 124 (range: 26-208) wk. Two patients registered peak ALT elevations of more than 10 times upper limit of normal, one of whom had the highest ALT (>17 X ULN) at the baseline. ALT level at timepoints 3 and 4 were similar to the baseline level at timepoint 1 (P>0.05). Five of the nine (56%) patients normalized their ALT after a median duration of 8 (range: 4-14) wk, two of whom achieved HBeAg seroconversion.

(3) Group II (patients with cirrhosis), n = 10 (Figure 3).

Six patients (60%) had abnormal ALT at the baseline (Figure 3A). All patients showedALT improvement after treatment with lamivudine (Wilcoxon signed Rank Test, P = 0.015). With the emergence of genotypic resistance, abnormal ALT elevations occurred in five patients (50%) after a median follow-up of 64 (range: 34-102) wk. The development of abnormal ALT at timepoint 3 compared to timepoint 2 was statistically significant (P = 0.017). When ALT levels among timepoints 1, 3, and 4 were compared, no significant difference was found. All the five patients with flares of ALT normalized their ALT level after a median duration of 4 (range: 4-8 wk).

CPT score analysis showed a similar trend in this group (Figure 3B). The CPT score at timepoint 2 showed significant improvement compared to timepoint 1 (Wilcoxon Signed Rank, P = 0.016) but deteriorated with the emergence of resistance at timepoint 3 (Wilcoxon Signed Rank, P = 0.041). No statistical significance was detected between CPT Score at timepoint 1 and timepoint 3 as well as between timepoints 1 and 4, with follow-up median duration of 64 wk after resistance (range 34-102). Three patients died from liver decompensation at 42, 78, and 96 wk, respectively after resistance developed, two of whom had the poorest pretreatment CPT score. None of the patients achieved HBeAg seroconversion although 40% (4 out of 10) were eAg negative Hepatitis B cirrhotics to begin with.

At univariate analysis, only the baseline ALT in non-cirrhotics and the baseline CPT score in cirrhotics were predictive of phenotypic resistance (P = 0.018 and P = 0.038, respectively, Table 2).

Multivariate analysis was then performed with these two parameters. Using logistic regression analysis, the baseline ALT was shown to be significantly predictive of phenotypic resistance (OR 9.6, 95%CI 1.2-4.0, P = 0.03). The peak ALT level post resistance also correlated with the baseline ALT. (Spearman’s r = 0.441, P = 0.027).

Similarly for CPT score, regression analysis showed baseline CPT score to be predictive of phenotypic resistance in terms of deterioration in CPT score after resistance (P = 0.022). Every additional CPT score at baseline predicts an additional 1.19 CPT score after resistance (B = 1.19, 95% CI: 0.235-2.15). Expectedly, peak CPT score after resistance showed strong correlation with baseline CPT score (Spearman’s r = 0.785, P = 0.007).

Interestingly, neither the pretreatment nor the peak HBV DNA post-resistance were shown to be predictive of phenotypic resistance although the peak HBV DNA level post-resistance was noted to correlate with the pretreatment HBV DNA level (Spearman’s r = 0.414, P = 0.013).

The most important finding of our study was that the course of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B was generally benign except in cirrhotics. In Group IA (patients with normal baseline ALT), despite the emergence of lamivudine resistance, most (10 of 13, 77%) of the patients maintained normal ALT up to median follow-up of 96 wk. In addition, all three patients in Group IA who developed elevated ALT subsequently normalized their ALT level on follow-up. In Group IB (patients with persistently elevated baseline ALT), lamivudine normalized ALT during therapy, but upon development of resistance, ALT increased in 75% of patients. However, only 4/12 (33%) of patients continued to have persistently elevated ALT on follow-up. Finally, in Group II (patients with decompensated cirrhosis), there was normalization of ALT levels and reduction in CPT scores during lamivudine therapy, but both parameters increased to baseline levels once lamivudine resistance occurred.

Thus the clinical picture of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus demonstrates a spectrum of disease from normal ALT to hepatitis B flares and liver decompensation. Our findings suggest that at the peak of abnormality, the clinical picture correlates most closely with baseline clinical characteristics of the patient. On subsequent follow-up however, the course was relatively benign except for cirrhotics.

The inclusion of patients with normal baseline ALT (Group 1A) provided an invaluable group of patients for studying the pathogenic effects of lamivudine-resistant Hepatitis B virus. This group of patients were treated with lamivudine only because they were part of the Asian Lamivudine Multicenter Trial. Yet on developing lamivudine resistance, most of them retained normal ALT in their follow up. Even in the few who had transient abnormal ALT, these universally resolved in contrast to those with abnormal baseline ALT or liver function. This suggests that lamivudine-resistant virus may not be more pathogenic than the wildtype virus. Although further study with larger number of patients is needed to confirm this, such study would be difficult to perform as clinical guidelines from America, Europe and Asia did not recommend lamivudine treatment for patients with normal baseline ALT levels[20-22].

Our findings also fit the known biology of HBV. Clinical disease in chronic Hepatitis B is a complex interplay between the virus and the immune system. Mutations in the YMDD motif confer resistance to lamivudine and allow high viral replication to resume. On the other hand, it is the mutations in the core region that have been most closely associated with increased immune responses to the virus[23].

Our study complements that of Yuen, who concluded that the majority of patients with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B flares recovered except some with cirrhosis[24]. In our patients with abnormal baseline ALT, although 75% had elevation of ALT at any time, only 33% had persistently elevated ALT on prolonged follow-up suggesting that the final clinical outcome in those without cirrhosis generally shows a benign course. Similarly, Lok[25] also concluded that lamivudine-resistance led to good outcomes in non-cirrhotics, but this cannot be extrapolated to cirrhotics. Cirrhotic patients, having poorer liver reserve, are less able to tolerate the further necroinflammation that may resume with the return of viral replication in those phenotypically susceptible. Our cohort of cirrhotic patients (Group II) developed decompensation following lamivudine resistance, resulting in death in 30% of patients. These findings concur with the results of NUCB 4006 (CALM study)[26]. In this landmark study, lamivudine therapy in cirrhotic patients proved to provide significant benefit in terms of reduced progression of liver disease and reduction in hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients who developed lamivudine-resistant mutations showed a reduction in this endpoint efficacy, as we have shown, developing progression of their liver disease. Nevertheless, they still had less clinical endpoints than patients on placebo. Unlike the CALM study which enrolled patients with early and non-decompensated cirrhosis, most of the cirrhotic patients in our study had decompensated liver disease and had poor outcomes when lamivudine resistance developed.

We acknowledge the following limitations of our study. Firstly, we did not have histological confirmation of progression of liver disease. However, abnormal ALT has been accepted as a good surrogate marker for necroinf-lammation of the liver[27]. In addition, an increase in CPT score clearly signifies progressive liver damage and deterioration. Consequently, we feel that the lack of histological data does not detract from the findings of this study. Although our sample size was relatively small, the spectrum of patients included in our study is typical of those seen in a normal hepatology practice or hospital, rather than the pre-selected patients included in clinical trials. In addition, the findings in general are also observed in larger clinical studies. Our study also includes patients with normal ALT and decompensated cirrhosis, which have not been previously described. The duration of follow-up in our series was 102 wk, longer than in most other published studies[8,12,24].

We believe the results of our study could have two therapeutic implications. Firstly, the clinical severity of lamivudine-resistant HBV resembled the baseline phenotype, although on follow-up, the vast majority of the increased ALT normalized. Recent updated American guidelines for Hepatitis B recommends options of continuing or stopping lamivudine or converting to other antiviral drug when lamivudine resistance develops, depending on the patient’s clinical state, ALT and HBV DNA levels[20]. Our study suggests that baseline activity can be used as predictive factor in identifying patients who are likely to resume active disease and who thus, should be monitored more closely. Secondly, in patients with poor liver reserve at baseline who developed lamivudine resistance, additional rescue therapy such as adefovir dipivoxil should be instituted early, before clinical deterioration occurred.

In conclusion, the clinical phenotype of patients with genotype resistance to lamivudine resembled the baseline clinical phenotype, suggesting loss of virus suppression and return to the pre-treatment state. Patients with high baseline ALT level or CPT score tended to return to a high ALT level or CPT score once lamivudine resistance occurred. With time, there was normalization of raised ALT levels in those with non-cirrhotic lamivudine resistance. Consequently, in treatment of hepatitis B, lamivudine therapy need not be stopped prematurely for fear of developing more pathogenic lamivudine-resistant strains. However, patients with cirrhosis, particularly decompensated cirrhosis, need to be monitored closely and adefovir dipivoxil started expediently when resistance occurs.

We would like to thank GlaxoSmithkline (Singapore) Private Limited for permission and access to the data for patients in the Asian Multicentre Lamivudine Trial, and Ms. Shen Liang from the Clinical Trials and Epidemiology Research Unit, Singapore Ministry of Health, for statistical support.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Lai CL, Chien RN, Leung NW, Chang TT, Guan R, Tai DI, Ng KY, Wu PC, Dent JC, Barber J. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:61-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1381] [Cited by in RCA: 1347] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Wright TL, Perrillo RP, Hann HW, Goodman Z, Crowther L, Condreay LD, Woessner M, Rubin M. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1256-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1054] [Cited by in RCA: 1008] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Villeneuve JP, Condreay LD, Willems B, Pomier-Layrargues G, Fenyves D, Bilodeau M, Leduc R, Peltekian K, Wong F, Margulies M. Lamivudine treatment for decompensated cirrhosis resulting from chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2000;31:207-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leung NW, Lai CL, Chang TT, Guan R, Lee CM, Ng KY, Lim SG, Wu PC, Dent JC, Edmundson S. Extended lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B enhances hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion rates: results after 3 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2001;33:1527-1532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lai CL, Dienstag J, Schiff E, Leung NW, Atkins M, Hunt C, Brown N, Woessner M, Boehme R, Condreay L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 490] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fu L, Cheng YC. Role of additional mutations outside the YMDD motif of hepatitis B virus polymerase in L(-)SddC (3TC) resistance. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1567-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Melegari M, Scaglioni PP, Wands JR. Hepatitis B virus mutants associated with 3TC and famciclovir administration are replication defective. Hepatology. 1998;27:628-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liaw YF, Chien RN, Yeh CT, Tsai SL, Chu CM. Acute exacerbation and hepatitis B virus clearance after emergence of YMDD motif mutation during lamivudine therapy. Hepatology. 1999;30:567-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim JW, Lee HS, Woo GH, Yoon JH, Jang JJ, Chi JG, Kim CY. Fatal submassive hepatic necrosis associated with tyrosine-methionine-aspartate-aspartate-motif mutation of hepatitis B virus after long-term lamivudine therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:403-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Leung NW, Chan HL, Sung JJ. How good is 1 year lamivudine treatment in HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B patients with elevated ALT levels? Experience from a regional hospital.[ABSTRACT]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:212. |

| 11. | Kobayashi S, Ide T, Sata M. Detection of YMDD motif mutations in some lamivudine-untreated asymptomatic hepatitis B virus carriers. J Hepatol. 2001;34:584-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yuen MF, Sablon E, Hui CK, Yuan HJ, Decraemer H, Lai CL. Factors associated with hepatitis B virus DNA breakthrough in patients receiving prolonged lamivudine therapy. Hepatology. 2001;34:785-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mutimer D, Pillay D, Dragon E, Tang H, Ahmed M, O'Donnell K, Shaw J, Burroughs N, Rand D, Cane P. High pre-treatment serum hepatitis B virus titre predicts failure of lamivudine prophylaxis and graft re-infection after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 1999;30:715-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zöllner B, Petersen J, Schröter M, Laufs R, Schoder V, Feucht HH. 20-fold increase in risk of lamivudine resistance in hepatitis B virus subtype adw. Lancet. 2001;357:934-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lok AS, Hussain M, Cursano C, Margotti M, Gramenzi A, Grazi GL, Jovine E, Benardi M, Andreone P. Evolution of hepatitis B virus polymerase gene mutations in hepatitis B e antigen-negative patients receiving lamivudine therapy. Hepatology. 2000;32:1145-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liaw YF, Leung NW, Chang TT, Guan R, Tai DI, Ng KY, Chien RN, Dent J, Roman L, Edmundson S. Effects of extended lamivudine therapy in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 532] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Krajden M, Minor J, Cork L, Comanor L. Multi-measurement method comparison of three commercial hepatitis B virus DNA quantification assays. J Viral Hepat. 1998;5:415-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Stuyver LJ, Locarnini SA, Lok A, Richman DD, Carman WF, Dienstag JL, Schinazi RF. Nomenclature for antiviral-resistant human hepatitis B virus mutations in the polymerase region. Hepatology. 2001;33:751-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lindh M, Gonzalez JE, Norkrans G, Horal P. Genotyping of hepatitis B virus by restriction pattern analysis of a pre-S amplicon. J Virol Methods. 1998;72:163-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update of recommendations. Hepatology. 2004;39:857-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | de Franchis R, Hadengue A, Lau G, Lavanchy D, Lok A, McIntyre N, Mele A, Paumgartner G, Pietrangelo A, Rodés J. EASL International Consensus Conference on Hepatitis B. 13-14 September, 2002 Geneva, Switzerland. Consensus statement (long version). J Hepatol. 2003;39 Suppl 1:S3-25. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Liaw YF, Leung N, Guan R, Lau GK, Merican I. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: an update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:239-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Koziel MJ. The immunopathogenesis of HBV infection. Antivir Ther. 1998;3:13-24. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Yuen MF, Kato T, Mizokami M, Chan AO, Yuen JC, Yuan HJ, Wong DK, Sum SM, Ng IO, Fan ST. Clinical outcome and virologic profiles of severe hepatitis B exacerbation due to YMDD mutations. J Hepatol. 2003;39:850-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lok AS, Lai CL, Leung N, Yao GB, Cui ZY, Schiff ER, Dienstag JL, Heathcote EJ, Little NR, Griffiths DA. Long-term safety of lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1714-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 584] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, Tanwandee T, Tao QM, Shue K, Keene ON, Dixon JS, Gray DF, Sabbat J. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1739] [Cited by in RCA: 1740] [Article Influence: 82.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cahen DL, van Leeuwen DJ, ten Kate FJ, Blok AP, Oosting J, Chamuleau RA. Do serum ALAT values reflect the inflammatory activity in the liver of patients with chronic viral hepatitis? Liver. 1996;16:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |