Published online Jan 14, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i2.305

Revised: June 28, 2004

Accepted: July 17, 2004

Published online: January 14, 2005

Outpatient percutaneous liver biopsy is a common practice in the differential diagnosis and treatment of chronic liver disease. The major complication and mortality rate were about 2-4% and 0.01-0.33% respectively. Arterio-portal fistula as a complication of percutaneous liver biopsy was infrequently seen and normally asymptomatic. Hemobilia, which accounted for about 3% of overall major percutaneous liver biopsy complications, resulted rarely from arterio-portal fistula We report a hemobilia case of 68 years old woman who was admitted for abdominal pain after liver biopsy. The initial ultrasonography revealed a gallbladder polypoid tumor and common bile duct (CBD) dilatation. Blood clot was extracted as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed hemobilia. The patient was shortly readmitted because of recurrence of symptoms. A celiac angiography showed an intrahepatic arterio-portal fistula. After superselective embolization of the feeding artery, the patient was discharged uneventfully. Most cases of hemobilia caused by percutaneous liver biopsy resolved spontaneously. Selective angiography embolization or surgical intervention is reserved for patients who failed to respond to conservative treatment.

- Citation: Lin CL, Chang JJ, Lee TS, Lui KW, Yen CL. Gallbladder polyp as a manifestation of hemobilia caused by arterial-portal fistula after percutaneous liver biopsy: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(2): 305-307

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i2/305.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i2.305

After the first report of liver biopsy by Paul Ehrlich in 1883[1], percutaneous liver biopsy has become a crucial diagnostic tool in liver diseases. Ultrasonography-guided percutaneous liver biopsy has been shown to increase the diagnostic yield and significantly decrease complications even on outpatients[2-6]. The incidence of hemobilia after percutaneous liver biopsy was reported to be 0.023% among 12750 patients in a liver transplantation center in 1993[7] accounting for 11.5% of all major complications. In a retrospective study of greater case number, the overall major complication rate of percutaneous liver biopsy was about 2.2%[8], of which hemobilia accounted for 2.7% of all complications (4 cases out of 68276 patients). Arterio-portal fistula as a cause of liver- biopsy related hemobilia was even less frequent. Arterio-portal fistula was seen in only one case in Van Thiel’s report[7]. Here, we report a case of hemobilia caused by arterio-portal fistula after percutaneous liver biopsy with an initial presentation of abdominal pain and ultrasound finding of gallbladder polypoid mass.

A 68 year-old female patient suffered from chronic C hepatitis for years. She received a percutaneous liver biopsy to evaluate the pathologic change after combination treatment of interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin therapy. The initial physical examination before liver biopsy was unremarkable. The hemoglobin, prothrombin time, and bleeding time were normal. Percutaneous liver biopsy was conducted under ultrasonography guidance with a 2.8-mm Menghini-type aspiration needle. After liver biopsy, transient hypotension was noted during the first two hours of in-hospital observation. The patient was discharged 6 h later.

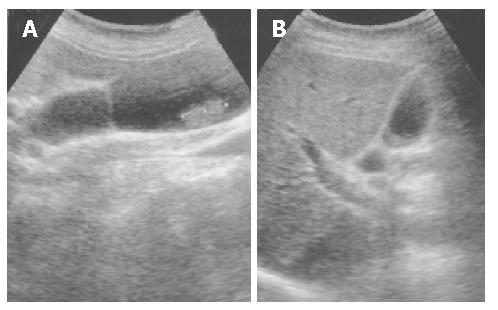

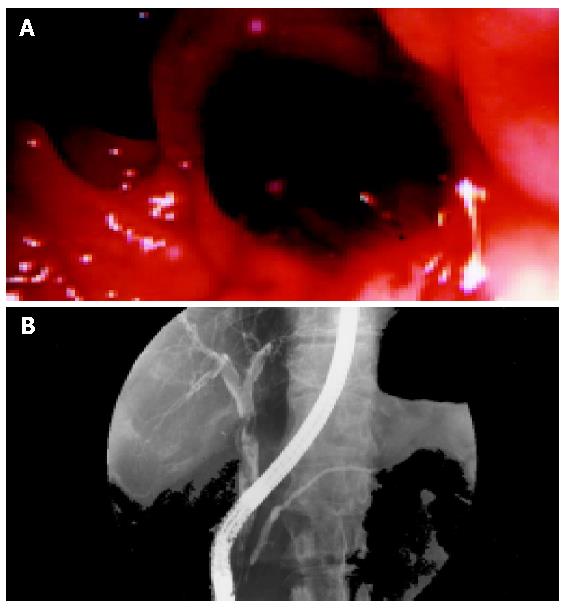

Two days later, however, the patient complained of epigastric and right subcostal pain without nausea, melena, hematemesis, or hematochezia. She visited our emergency room where an ultrasonography revealed a polypoid echogenic mass in the gallbladder wall and a mild dilatation of the common bile duct (Figure 1A) An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed showing blood emanating from the edematous ampullar vater (Figure 2A). The intrahepatic ducts and common bile duct were partially opacified which is consistent with blood impaction of bile ducts (Figure 2B). An endoscopic sphincterotomy was conducted removing blood clot from the common bile duct. The symptoms were alleviated as ultrasonography showed disappearance of gallbladder sludge and polypoid mass. She was discharged seven days later.

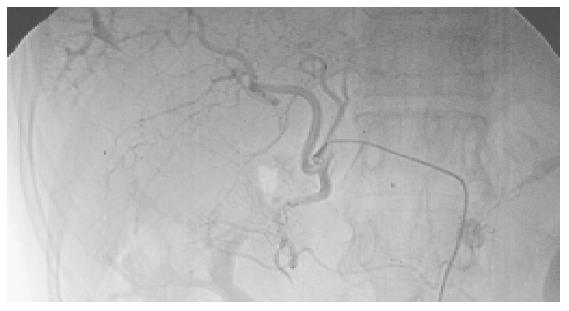

The patient was shortly readmitted for recurrence of right upper quadrant pain. Arteriography was conducted demonstrating an arterio-portal fistula in segment VII of the liver between a branch of right hepatic artery and right portal vein (Figure 3). After superselective catheterization of the feeding artery, embolization was performed with gel-foam. A repeat angiography demonstrated occlusion of the arterio-portal fistula. The patient was uneventful afterward and discharged fiver days after the procedure. No recurrence of bleeding was observed during the following 6 mo.

Hemobilia was first described by Glisson in 1654[9] in a postmortem diagnosis of a young adult stabbed by a sword in the liver. Sandblom in 1948[10] used hemobilia[11,12] as a term of hemorrhage arising from trauma in the biliary tract. With increasing practice of percutaneous liver biopsy, pure ethanol injection, radiofrequency ablation and percutaneous biliary drainage, iatrogenic trauma of biliary tract has been responsible for up to 60% of the hemobilia[13-20] whereas accidental abdominal injury was previously dominant[21].

Ultrasound guided liver biopsy was aimed to decrease complications following percutaneous liver biopsy[4]. However, a controversial report by Van thiel in 1993[7] demonstrated a higher complication rate (3.6%) using an ultrasound-guided cutting needle in 2 of 55 patients who were mostly with a hepatic neoplasm. The underlying disease, coagulative status, the type and the diameter of biopsy needles used[8], and the numbers of needle passes[22] seemed to determine the rate of complications rather than if ultrasonography guided[23], although ultrasound assisted biopsy helped to avoid undesired puncture of surrounding organs.

Classical clinical features of hemobilia include right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage[22,24] with less than 50% patients showing full triads[25]. The interval between percutaneous liver biopsy and the symptom onset may be as early as the same day on biopsy up to 21 d after percutaneous liver biopsy with a mean of 5 days[22,26]. The findings of hemobilia on ultrasonography varied depending on the rapidity and severity of the bleeding. Acute intracholecystic bleeding typically manifested as echogenic, non-acoustic polypoid mass[27,28]. The echo texture became reticular, stranding sludge as the clot began to lyse. The border of the clot became concave. The appearance of gallbladder polypoid mass as seen in this case underscored the importance of a high index of suspicion of hemobilia in patients undergoing percutaneous liver biopsy with previously normal ultrasonography. After treatment with arterial embolizaton, the echogenic sludge disappeared between 3-7 d as demonstrated in this case (Figure 1B).

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography as well as endoscopy were confirmative in the diagnosis of hemobilia in 40-60% of the cases[13], when showing blood emanating from the ampulla or within the biliary trees[22]. Sphincterectomy and blood clot extraction could release the tension of the biliary trees and alleviate the pain caused by distension of the ducts[29].

Angiographic findings of hemobilia included arterio-portal fistula, arterio-biliary fistula and pseudoaneurysm. Arterio-portal fistula as a complication of percutaneous liver biopsy (PLB) was seen in only one of 3 hemobilia cases in Van’s series[7]. Okuda et al[30] estimated the incidence of arterio-portal fistula after PLB was approximately 5%, but normally asymptomatic. The actual incidence of arterio-portal fistula induced hemobilia has not been well documented as it was mostly case reported.

Hemobilia recovered spontaneously in most of the cases depending on the severity of the bleeding[30]. Selective arterial embolization for hemobilia was first reported in 1976[31]. The success rate was more than 90-95% using gel-foam or histoacryl with a low morbidity[8,17,22,31,32] Laparotomy for hepatic arterial ligation or hepatectomy was reserved for cases that failed to respond to conservative treatment and hepatic arterial embolization[11,12,33].

In conclusion, arterio-portal fistula after percutaneous liver biopsy is usually asymptomatic. Hemobilia resulting from arterio-portal fistula remains mostly case - reported. Selective arterial embolization provides a successful modality of treatment if conservative treatment fails. Surgical treatment is reserved for selective cases that do not respond to the angiographic embolization.

Assistant Editor Guo SY Edited by Wang XL

| 1. | Sherlock S, Dooley J. Disease of the liver and biliary system. 11th ed. Oxford: Blackwell sci pub 2002; 37. |

| 2. | Caturelli E, Giacobbe A, Facciorusso D, Bisceglia M, Villani MR, Siena DA, Fusilli S, Squillante MM, Andriulli A. Percutaneous biopsy in diffuse liver disease: increasing diagnostic yield and decreasing complication rate by routine ultrasound assessment of puncture site. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1318-1321. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Younossi ZM, Teran JC, Ganiats TG, Carey WD. Ultrasound-guided liver biopsy for parenchymal liver disease: an economic analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:46-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rossi P, Sileri P, Gentileschi P, Sica GS, Forlini A, Stolfi VM, De Majo A, Coscarella G, Canale S, Gaspari AL. Percutaneous liver biopsy using an ultrasound-guided subcostal route. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:128-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Farrell RJ, Smiddy PF, Pilkington RM, Tobin AA, Mooney EE, Temperley IJ, McDonald GS, Bowmer HA, Wilson GF, Kelleher D. Guided versus blind liver biopsy for chronic hepatitis C: clinical benefits and costs. J Hepatol. 1999;30:580-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Garcia-Tsao G, Boyer JL. Outpatient liver biopsy: how safe is it? Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:150-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS, Wright H, Tzakis A. Liver biopsy. Its safety and complications as seen at a liver transplant center. Transplantation. 1993;55:1087-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Piccinino F, Sagnelli E, Pasquale G, Giusti G. Complications following percutaneous liver biopsy. A multicentre retrospective study on 68,276 biopsies. J Hepatol. 1986;2:165-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 850] [Cited by in RCA: 804] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rossi P, Sileri P, Gentileschi P, Sica GS, Ercoli L, Coscarella G, De Majo A, Gaspari AL. Delayed symptomatic hemobilia after ultrasound-guided liver biopsy: a case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1659-1662. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sandblom P. Hemorrhage into the biliary tract following trauma; traumatic hemobilia. Surgery. 1948;24:571-586. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Merrell SW, Schneider PD. Hemobilia--evolution of current diagnosis and treatment. West J Med. 1991;155:621-625. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Bloechle C, Izbicki JR, Rashed MY, el-Sefi T, Hosch SB, Knoefel WT, Rogiers X, Broelsch CE. Hemobilia: presentation, diagnosis, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1537-1540. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Curet P, Baumer R, Roche A, Grellet J, Mercadier M. Hepatic hemobilia of traumatic or iatrogenic origin: recent advances in diagnosis and therapy, review of the literature from 1976 to 1981. World J Surg. 1984;8:2-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoshida J, Donahue PE, Nyhus LM. Hemobilia: review of recent experience with a worldwide problem. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:448-453. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Rossi P, Sileri P, Gentileschi P, Sica GS, Ercoli L, Coscarella G, De Majo A, Gaspari AL. Delayed symptomatic hemobilia after ultrasound-guided liver biopsy: a case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1659-1662. |

| 16. | Obi S, Shiratori Y, Shiina S, Hamamura K, Kato N, Imamura M, Teratani T, Sato S, Komatsu Y, Kawabe T. Early detection of haemobilia associated with percutaneous ethanol injection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:285-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Croutch KL, Gordon RL, Ring EJ, Kerlan RK, LaBerge JM, Roberts JP. Superselective arterial embolization in the liver transplant recipient: a safe treatment for hemobilia caused by percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:118-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Francica G, Marone G, Solbiati L, D'Angelo V, Siani A. Hemobilia, intrahepatic hematoma and acute thrombosis with cavernomatous transformation of the portal vein after percutaneous thermoablation of a liver metastasis. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:926-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Livraghi T, Goldberg SN, Lazzaroni S, Meloni F, Solbiati L, Gazelle GS. Small hepatocellular carcinoma: treatment with radio-frequency ablation versus ethanol injection. Radiology. 1999;210:655-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 994] [Cited by in RCA: 878] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Machicao VI, Lukens FJ, Lange SM, Scolapio JS. Arterioportal fistula causing acute pancreatitis and hemobilia after liver biopsy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:481-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sandblom P, Mirkovitch V. Minor hemobilia. Clinical significance and pathophysiological background. Ann Surg. 1979;190:254-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lichtenstein DR, Kim D, Chopra S. Delayed massive hemobilia following percutaneous liver biopsy: treatment by embolotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1833-1838. [PubMed] |

| 23. | McGill DB, Rakela J, Zinsmeister AR, Ott BJ. A 21-year experience with major hemorrhage after percutaneous liver biopsy. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1396-1400. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Lee SP, Tasman-Jones C, Wattie WJ. Traumatic hemobilia: a complication of percutaneous liver biopsy. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:941-944. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Richardson SC, Young TL. Liver biopsy-associated hemobilia treated conservatively. Tenn Med. 1998;91:141-142. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Taylor JD, Carr-Locke DL, Fossard DP. Bile peritonitis and hemobilia after percutaneous liver biopsy: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography demonstration of bile leak. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:262-264. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Laing FC, Frates MC, Feldstein VA, Goldstein RB, Mondro S. Hemobilia: sonographic appearances in the gallbladder and biliary tree with emphasis on intracholecystic blood. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:537-543. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Grant EG, Smirniotopoulos JG. Intraluminal gallbladder hematoma: sonographic evidence of hemobilia. J Clin Ultrasound. 1983;11:507-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jornod P, Wiesel PH, Pescatore P, Gonvers JJ. Hemobilia, a rare cause of acute pancreatitis after percutaneous liver biopsy: diagnosis and treatment by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3051-3054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Okuda K, Musha H, Nakajima Y, Takayasu K, Suzuki Y, Morita M, Yamasaki T. Frequency of intrahepatic arteriovenous fistula as a sequela to percutaneous needle puncture of the liver. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:1204-1207. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Walter JF, Paaso BT, Cannon WB. Successful transcatheter embolic control of massive hematobilia secondary to liver biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;127:847-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wagner WH, Lundell CJ, Donovan AJ. Percutaneous angiographic embolization for hepatic arterial hemorrhage. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1241-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dousset B, Sauvanet A, Bardou M, Legmann P, Vilgrain V, Belghiti J. Selective surgical indications for iatrogenic hemobilia. Surgery. 1997;121:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |