Published online Mar 21, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i11.1725

Revised: August 20, 2004

Accepted: October 6, 2004

Published online: March 21, 2005

We report a case of candidal liver abscesses and concomitant candidal cholecystitis in a diabetic patient, in whom differences were noted relative to those found in patients with hematologic malignancies. In our case, the proposed entry route of infection is ascending retrograde from the biliary tract. Bile and aspirated pus culture repeatedly tested positive, and blood negative, for Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. Cholecystitis was cured by percutaneous gallbladder drainage and amphotericin B therapy. The liver abscesses were successfully treated by a cumulative dosage of 750 mg amphotericin B. We conclude that in cases involving less immunocompromised patients and those without candidemia, a lower dosage of amphotericin B may be adequate in treating candidal liver abscesses.

- Citation: Lai CH, Chen HP, Chen TL, Fung CP, Liu CY, Lee SD. Candidal liver abscesses and cholecystitis in a 37-year-old patient without underlying malignancy. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(11): 1725-1727

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i11/1725.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i11.1725

Candidal liver abscess is a rare disease, and most of the reported cases have been diagnosed in patients with hematologic malignancies during periods of neutropenia resolution[1,2]. In a review by Thaler et al, only 8 of 73 patients had an underlying disease other than a malignancy. Clinical features and management of this disease may be different in those with a malignancy versus without a malignancy. We reported the case of a patient with diabetes mellitus in order to add further experience to the limited data regarding patients without malignancy.

A 37-year-old male, who was an alcoholic and heavy smoker, was admitted for right upper-quadrant abdominal colic, with pain radiating to the back, which had been present for 2 wk. Two years before this admission, he had suffered an accident that resulted in pancreatic rupture. Partial pancreatectomy was performed and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus was noted soon. Since then, he had suffered from several episodes of pancreatitis. He visited our emergency department 1 year ago for treatment of biliary tract obstruction caused by pancreatic pseudocyst. Meanwhile, diabetic ketoacidosis and pulmonary tuberculosis were also found, which were appropriately treated.

On admission, poor nutritional status was evident (body weight 49 kg and body mass index 17.16 kg/m2). His temperature was 37.6 °C, blood pressure was 101/63 mmHg, pulse rate was 126 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 17/min. Remarkable findings on physical examination included rales over the left upper-lung field, tenderness over the right upper-abdominal quadrant with a positive Murphy’s sign, but without rebounding pain.

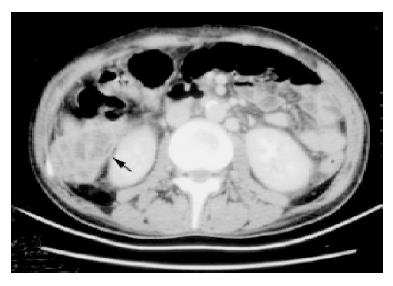

Laboratory examinations revealed a white blood cell count of 16.5×109/L, with 88% of neutrophils, a hemoglobin level of 110 g/L, and a platelet count of 331×109/L. Serum chemistry results revealed the following values: glucose level, 324 mg/dL; sodium, 130 mmol/L; potassium, 3.7 mmol/L; blood urea nitrogen, 5 mg/dL; and creatinine, 0.8 mg/dL. Results of a liver function test performed on admission were as follow: aspartate aminotransferase, 26 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 16 U/L; total bilirubin 2 mg/dL (normal range, 0.2-1.6 mg/dL); direct bilirubin, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 0-0.3 mg/dL); alkaline phosphatase, 1645 IU/L (normal range, 10-100 IU/L); and gamma glutamyl transferase, 1214 IU/L (normal range, 8-61 IU/L). The initial C-reactive protein concentration was 12.06 mg/dL (normal value, <0.5 mg/dL). The amylase and blood gas analyses were within normal limits. Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen revealed multiple hypoechoic lesions over bilateral liver lobes, with the largest one located over segment 6, which had ruptured but was localized in the subhepatic area (Figure 1). Other findings included features suggestive of cholecystitis with gallbladder empyema (Figure 2), chronic pancreatitis, intrahepatic and common bile duct dilatation, splenomegaly, and splenic vein occlusion with collateral circulation. Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage was performed and a pigtail was inserted into the ruptured abscess, but was removed 3 d after no drainage whatsoever occurred. The bile culture, aspirated pus from the abscess and blood, was negative for bacteria (aerobic and anaerobic) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. However, cultures of bile and aspirated pus yielded yeast that was subsequently identified as Candida glabrata and Candida albicans. Initially, enteral fluconazole was given (6 mg/kg per d). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography revealed stricture over the distal common bile duct but without evidence of malignancy. Endoscopic papillotomy was performed, and a biliary prosthesis was placed. Both C. glabrata and C. albicans persisted in the bile and liver abscess after 15 d of fluconazole therapy. Susceptibility testing was done using the ATB Fungus kit (bioMérieux, France). Both species were susceptible to amphotericin B (AmB) (minimal inhibitory concentration <1.00 μg/mL) and flucytosine (<0.25 μg/mL). Therefore, antifungal therapy was switched to intravenous AmB (0.5 mg/kg per d). The bile and liver aspirates were sterile 2 wk after this treatment. After a cumulative dosage of 750 mg AmB, the patient’s symptoms had subsided progressively, laboratory data were normalized, and the CT scan showed no evidence of cholecystitis and only a small residual hypoechoic lesion without enhancement over segment 6. Enteral fluconazole (6 mg/kg per d) was prescribed for an additional month.

Diabetes mellitus was well controlled by insulin administration during hospitalization. By his 2-year follow-up, he had suffered from several episodes of pancreatitis and bacterial cholangitis caused by biliary prosthesis occlusion with sludge, which was treated with percutaneous drainage and antibiotics, however, no recurrence of candidal liver abscess and cholecystitis was found.

Most of the candidal liver abscesses in patients with hematologic malignancies are a manifestation of disseminated candidiasis and have a high mortality rate[2,3]. However, this disease can also be acquired by fungemia from the portal vein[1,4] or an ascending retrograde infection from the biliary tree[5,6], which is the proposed route of infection, as the patient had a biliary stricture, and the infection was localized in the liver and gallbladder, but negative in other parts and without candidemia. Biliary stricture may lead to cholestasis, which in turn can allow micro-organisms from the gut to ascend into the biliary tract. In patients with hematologic malignancies, the yield of positive culture is often less than 50%, with the diagnosis usually based on microscopic examination or histopathological finding from deep tissues[1,3,4,7]. Nevertheless, fungal cultures had repeatedly been positive in our patient. Taking into consideration the negative cultures for other pathogens, pure culture for Candida, and good clinical response after AmB therapy, Candida was considered a causative pathogen in our case. Interestingly, the infection was caused by 2 species of Candida concomitantly. In fact, Domagk et al[8] also reported a case of common bile duct candidiasis caused simultaneously by C. albicans and C. glabrata. For patients with hematologic malignancies who have suffered from candidal liver abscesses, higher cumulative dosages of AmB (2-9 g) are recommended by most experts, because some evidence reveals that a cumulative dose of less than 2 g AmB correlated with residual lesions at autopsy[1,4,9]. Cases of hepatosplenic candidiasis that were successfully treated with fluconazole have been reported by Kauffman et al. The symptoms improved within 3-8 wk, but resolution of lesions on CT scan was noted after at least 1 mo of fluconazole therapy[10]. In addition, fluconazole concentrations in the bile were equal to or slightly higher than serum concentrations reported in the study conducted by Bozzette et al[11] . However, culture from the liver abscess and bile remained positive despite 2 wk of fluconazole therapy in our case, but became sterile 2 wk after AmB therapy. It is possible that longer course of therapy with fluconazole might have led to resolution of infection in our patient. Notably, the disease improved remarkably with only a cumulative dose of 750 mg AmB. However, he received fluconazole for an additional month, and the role of this therapy is difficult to assess.

The management for candidal cholecystitis is not well established. Surgical drainage or cholecystectomy is considered adequate treatment for isolated candidal cholecystitis in nonneutropenic patients, but the addition of antifungal therapy is required in critically ill or immunocompromised patients, or patients with extrabiliary tract candidiasis[12,13]. Our patient received cholecystotomy, endoscopic biliary drainage, and fluconazole as initial therapy. Again, the bile culture became sterile only after initiation of AmB. In a study by Adamson et al[14], AmB was concentrated in the bile and the outcome was favorable in their case of candidal cholecystitis treated with this antifungal agent.

In conclusion, candidal liver abscesses and cholecystitis are rare, especially in patients without malignancies. Mortality from candidal liver abscesses in patients with hematologic malignancy is high even with high cumulative dosage of AmB. However, in less immunocompromised patients and those without candidemia, this disease may be cured with a lower dosage of AmB.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Thaler M, Pastakia B, Shawker TH, O'Leary T, Pizzo PA. Hepatic candidiasis in cancer patients: the evolving picture of the syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:88-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Haron E, Feld R, Tuffnell P, Patterson B, Hasselback R, Matlow A. Hepatic candidiasis: an increasing problem in immunocompromised patients. Am J Med. 1987;83:17-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lewis JH, Patel HR, Zimmerman HJ. The spectrum of hepatic candidiasis. Hepatology. 1982;2:479-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tashjian LS, Abramson JS, Peacock JE. Focal hepatic candidiasis: a distinct clinical variant of candidiasis in immunocompromised patients. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:689-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Annunziata GM, Blackstone M, Hart J, Piper J, Baker AL. Candida (Torulopsis glabrata) liver abscesses eight years after orthotopic liver transplantation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;24:176-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McGuire N, Hutson J, Huebl H. Gangrenous cholecystitis secondary to Candida tropicalis infection in a patient with leukemia. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:367-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Anttila VJ, Ruutu P, Bondestam S, Jansson SE, Nordling S, Färkkilä M, Sivonen A, Castren M, Ruutu T. Hepatosplenic yeast infection in patients with acute leukemia: a diagnostic problem. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:979-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Domagk D, Bisping G, Poremba C, Fegeler W, Domschke W, Menzel J. Common bile duct obstruction due to candidiasis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:444-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sallah S. Hepatosplenic candidiasis in patients with acute leukemia: increasingly encountered complication. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:757-760. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kauffman CA, Bradley SF, Ross SC, Weber DR. Hepatosplenic candidiasis: successful treatment with fluconazole. Am J Med. 1991;91:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bozzette SA, Gordon RL, Yen A, Rinaldi M, Ito MK, Fierer J. Biliary concentrations of fluconazole in a patient with candidal cholecystitis: case report. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:701-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Morris AB, Sands ML, Shiraki M, Brown RB, Ryczak M. Gallbladder and biliary tract candidiasis: nine cases and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:483-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hiatt JR, Kobayashi MR, Doty JE, Ramming KP. Acalculous candida cholecystitis: a complication of critical surgical illness. Am Surg. 1991;57:825-829. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Adamson PC, Rinaldi MG, Pizzo PA, Walsh TJ. Amphotericin B in the treatment of Candida cholecystitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8:408-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |