Published online Dec 15, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i24.3659

Revised: May 6, 2004

Accepted: May 13, 2004

Published online: December 15, 2004

AIM: To study the early diagnosis and management of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

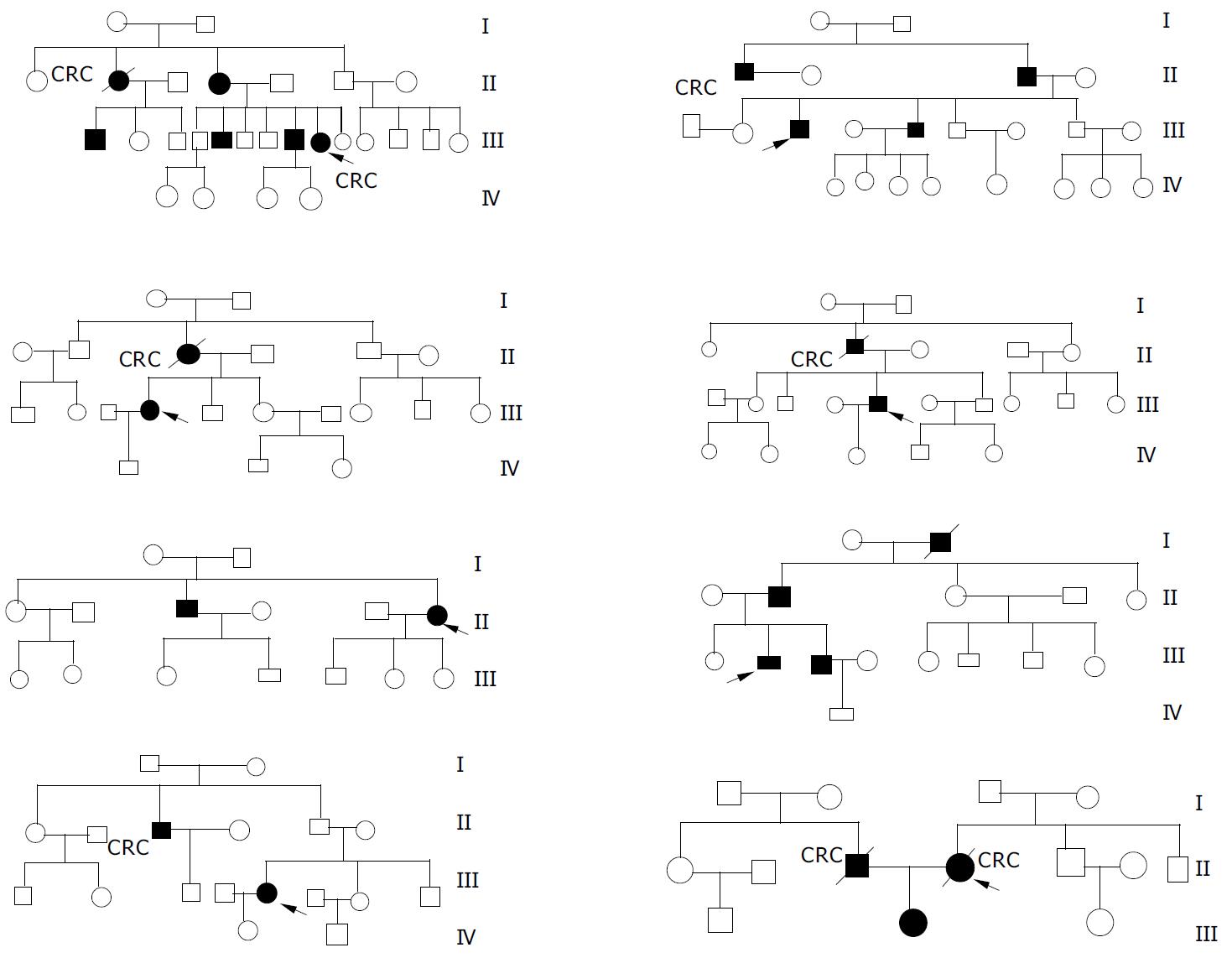

METHODS: Eight pedigrees of FAP were collected and their pedigree trees were protracted. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of FAP patients in these kindreds were analysed.

RESULTS: A total of 157 members were investigated in eight kindreds and 25 patients with FAP were diagnosed. The ratio of male patients and female patients was 16:9 and the average age at onset was 38 years. Among them, six patients died of cancer with a mortality rate of 28%, and 36% (9/25) FAP patients were diagnosed as synchronous colorectal cancer on the basis of FAP. A proband was diagnosed as synchronous colorectal cancer with liver metastasis and died 11 mo later after partial colectomy and hepatic metastatic lesion biopsy. The other seven probands received total abdominal colectomy and rectal mucosectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA), and one of them was diagnosed as synchronous colon cancer on the basis of FAP and was still alive after 7.5 years follow-up. Among the other seven patients with synchronous colorectal cancer on the basis of FAP underwent total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (IRA), one underwent total remnant rectum resection and ileostomy for recurrent carcinoma in the retained rectum 2.5 years later after the IRA and was still alive, while the others all died of recurrence with a median survival time of 4.6 years. Through close follow-up and termly endoscopic surveillance, three FAP patients were detected before presenting symptoms at the age of 18, 20 and 23 years, respectively. Prophylactic IPAA was performed and results were satisfactory after the patients were followed-up for 6, 1, and 8 years, respectively.

CONCLUSION: Pedigree investigation, close follow-up and termly endoscopic surveillance are very important for early detection of FAP. Prophylactic IPAA can give satisfactory results to FAP patients.

- Citation: He YL, Zhang CH, Huang MJ, Cai SR, Zhan WH, Wang JP, Wang JF. Clinical analysis of eight kindreds of familial adenomatous polyposis. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(24): 3659-3661

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i24/3659.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i24.3659

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), which usually begins at a mean age of 16 years (range, 7-36 years), is an autosomal dominant hereditary colon cancer predisposition syndrome, in which hundreds to thousands of precancerous colonic polyps can develop. Without colectomy, colon cancer is inevitable. The mean age of developing colon cancer in untreated individuals is 39 years (range, 34-43 years)[1]. Prophylactic colectomy has been considered to be the best treatment for familial adenomatous polyposis[2]. In this paper, data of eight pedigrees of FAP were analysed retrospectively. The role of surveillance endoscopy and the effect of different surgical procedures were evaluated.

We studied the patients with FAP and their families enrolled in our Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Registry from March 1991 to December 2003. Close follow-up and termly surveillance colonoscopy were performed and the results were analysed retrospectively. Pedigree trees were protracted according to their family history.

In our registry, eight probands had a family history. These eight pedigree trees were protracted (Figure 1). In these eight kindreds, a total of 157 members were investigated, among them 134 members were in the first to third generation with the age older than 14 years. As a result, 25 members (about 16%) were diagnosed as FAP with an average age of 38 years and the youngest patient was eighteen years old. The ratio of male patients and female patients was 16:9 and most of them were in the second and third generation. A total of 9 FAP patients (36%) were diagnosed as synchronous colorectal cancer, and six patients died of cancer with a mortality rate of 28%. Among 13 patients who had symptoms but no malignancy, 7 patients underwent total abdominal colectomy and rectal mucosectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) and others received total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (IRA). All of them were still alive and no cancer was found after a median follow-up time of 4.2 years and 5.6 years, respectively.

In these eight kindreds, one proband was diagnosed as advanced colon cancer and died 11 mo later after partial colectomy and hepatic metastatic lesion biopsy, and the other probands underwent IPAA, among them one was diagnosed as synchronous colon cancer on the basis of FAP and was still alive after 7.5 years follow-up. Through endoscopic surveillance, three FAP patients were detected before presenting symptoms at the age of 18, 20 and 23 years, respectively. Prophylactic IPAA was performed and results were satisfactory after the patients were followed-up for 6, 1, and 8 years, respectively. Among the other seven patients with synchronous colorectal cancer on the basis of FAP, who received total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (IRA), one underwent total remnant rectum resection and ileostomy for recurrent carcinoma in the retained rectum 2.5 years later after the IRA and was still alive, while the others all died of cancer recurrence with a median survival time of 4.6 years. However, the other seven patients without colorectal cancer were still alive although one was given IPAA and the others received IRA.

FAP is an autosomal dominant hereditary disease. Approximately 80% of individuals with FAP had a family history[3]. Offsprings of an affected individual had a 50% risk of the disease[4]. The prevalence of FAP is 1 per 16000 people to 1 per 8000 people. Though FAP historically accounted for about 0.5% of all colorectal cancers, this figure has been declining as more family members at-risk underwent successful treatment following early polyp detection and prophylactic colectomy[5-8]. In our study, the incidence rate of FAP in these eight kindreds was 16%, and most of the FAP patients were in the second and third generation without atavism. The average age of FAP patients was 38 years, and nine patients with FAP (36%) were in an advanced stage when they were diagnosed as colorectal cancer. Bulow[5] reported that since the establishment of the Danish Polyposis Register, the prevalence of colorectal cancer had decreased considerably and the prognosis had improved substantially. They made a conclusion that the work of the Danish Polyposis Register was probably the main cause of this improvement. Other studies[7-9] also showed that with pedigree investigation, close follow-up and termly endoscopic surveillance, more family members at-risk underwent successful treatment following early polyp detection and prophylactic colectomy, and the prevalence of colorectal cancer was considerably decreased and the prognosis was substantially improved. In our study, we established a FAP register in 1991, and then investigated all lineal and collateral relatives of FAP patients enrolled in our hospital and protracted their pedigree trees. Close follow-up and termly colonoscopy surveillance were performed to find early cases among the relatives at high risk. At the end, 3 FAP patients were detected before presenting symptoms at the age 18, 20 and 23 years, respectively. Prophylactic IPAA was performed and functional outcome and quality of life were satisfactory after the patients were followed-up for 6, 1 and 8 years, respectively. No patient was found with colorectal cancer or pouch adenoma or inflammation. Thus, we conclude that pedigree investigation, close follow-up and termly colonoscopy are feasible and effective methods for early diagnosis of FAP, although FAP has been found to be caused by mutations in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) (chromosomal loci 5q21-q22) and molecular genetic testing and genetic counseling are clinically available in some developed countries[6,10] while they are still in laboratories in China[11].

For individuals with classic FAP, prophylactic colectomy is recommended when adenomas emerge. Colectomy includes total colectomy and rectal mucosectomy with IPAA and subtotal colectomy with IRA. Although IRA has fewer complications and comfortable defecation function, it is not generally accepted by patients because carcinoma may develop in 40% retained rectum[12]. On the other hand, during IPAA all colorectal mucous membranes were removed to completely eliminate the risk of developing colonic carcinoma and a small reservoir was created to reduce the frequency of bowel movement. However, temporary ileostomy and creation of a reservoir might lead to more complications and increase the difficulty in operation[2,8]. Parc et al[13] found that young patients had a good quality of life after IPAA, and suggested that this procedure was well suitable for the youth. In our study, three symptom-free patients underwent IPAA and all had satisfactory results. Among thirteen patients who had symptoms but no malignancy, although 7 patients underwent IPAA and 6 patients underwent IRA, no carcinoma developed after they were followed-up for 4.2 years and 5.6 years, respectively. But for those patients with carcinoma, only one patient who underwent IPAA 7.5 years before was still alive, while the others who underwent IRA all died of cancer recurrence. Thus, we conclude that symptom-free patients should undergo prophylactic surgical procedure and IPAA should be preferred. Furthermore, IPAA should be the first choice for those patients with carcinoma.

Edited by Kumar M and Wang XL Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | de Vos tot Nederveen Cappel WH, Järvinen HJ, Björk J, Berk T, Griffioen G, Vasen HF. Worldwide survey among polyposis registries of surgical management of severe duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 2003;90:705-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Delaney CP, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Hammel J, Church JM, Hull TL, Senagore AJ, Strong SA, Lavery IC. Prospective, age-related analysis of surgical results, functional outcome, and quality of life after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2003;238:221-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Iwama T, Utsunomiya J. Anticipation phenomenon in familial adenomatous polyposis: an analysis of its origin. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:335-338. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Barrison AF, Smith C, Oviedo J, Heeren T, Schroy PC. Colorectal cancer screening and familial risk: a survey of internal medicine residents' knowledge and practice patterns. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1410-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bülow S. Results of national registration of familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2003;52:742-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Grady WM. Genetic testing for high-risk colon cancer patients. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1574-1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Keating J, Pater P, Lolohea S, Wickremesekera K. The epidemiology of colorectal cancer: what can we learn from the New Zealand Cancer Registry? N Z Med J. 2003;116:U437. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Church J, Kiringoda R, LaGuardia L. Inherited colorectal cancer registries in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:674-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Church J, Burke C, McGannon E, Pastean O, Clark B. Risk of rectal cancer in patients after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis: a function of available surgical options. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1175-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bisgaard ML, Ripa R, Knudsen AL, Bülow S. Familial adenomatous polyposis patients without an identified APC germline mutation have a severe phenotype. Gut. 2004;53:266-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hu NP, Zhan WH, Yan ZS, Ge MH, Lü XS. Protein truncation test of the APC gene in familial adenomatous polyposis. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:587-589. |

| 12. | Jang YS, Steinhagen RM, Heimann TM. Colorectal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:312-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Parc YR, Moslein G, Dozois RR, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, King JE. Familial adenomatous polyposis: results after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in teenagers. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:893-898; discussion 893-898;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |