Published online Aug 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i15.2218

Revised: October 23, 2003

Accepted: April 15, 2004

Published online: August 1, 2004

AIM: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) genomes in carriers from Hawaii have not been evaluated previously. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the distribution of HBV genotypes and their clinical relevance in Hawaii.

METHODS: Genotyping of HBV among 61 multi-ethnic carriers in Hawaii was performed by genetic methods. Three complete genomes and 61 core promoter/precore regions of HBV were sequenced directly.

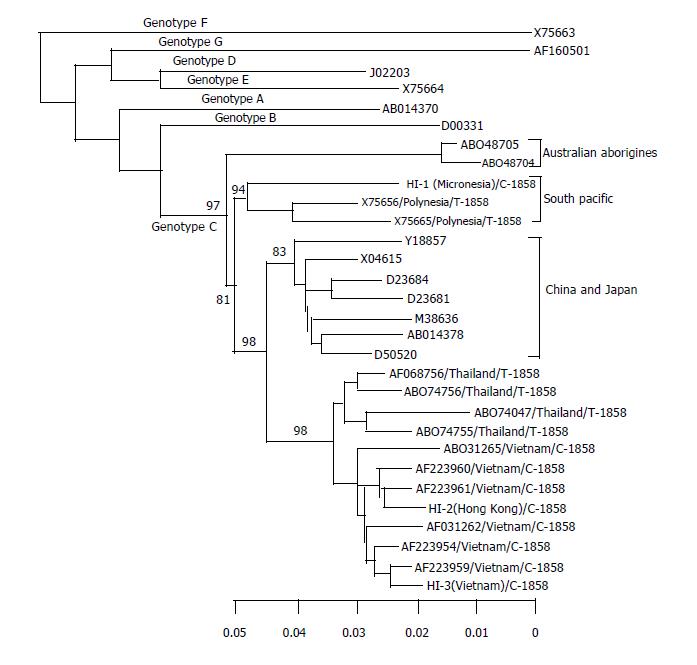

RESULTS: HBV genotype distribution among the 61 carriers was 23.0% for genotype A, 14.7% for genotype B and 62.3% for genotype C. Genotypes A, B and C were obtained from the carriers whose ethnicities were Filipino and Caucasian, Southeast Asian, and various Asian and Micronesian, respectively. All cases of genotype B were composed of recombinant strains with genotype C in the precore plus core region named genotype Ba. HBeAg was detected more frequently in genotype C than in genotype B (68.4% vs 33.3%, P < 0.05) and basal core promoter (BCP) mutation (T1762/A1764) was more frequently found in genotype C than in genotype B. Twelve of the 38 genotype C strains possessed C at nucleotide (nt) position 1858 (C -1858). However there was no significant difference in clinical characteristics between C-1858 and T-1858 variants. Based on complete genome sequences, phylogenetic analysis revealed one patient of Micronesian ethnicity as having C-1858 clustered with two isolates from Polynesia with T-1858. In addition, two strains from Asian ethnicities were clustered with known isolates in carriers from Southeast Asia.

CONCLUSION: Genotypes A, B and C are predominant types among multi-ethnic HBV carriers in Hawaii, and distribution of HBV genotypes is dependent on the ethnic background of the carriers in Hawaii.

- Citation: Sakurai M, Sugauchi F, Tsai N, Suzuki S, Hasegawa I, Fujiwara K, Orito E, Ueda R, Mizokami M. Genotype and phylogenetic characterization of hepatitis B virus among multi-ethnic cohort in Hawaii. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(15): 2218-2222

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i15/2218.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i15.2218

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is one of the major causes of chronic liver diseases including chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis (LC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1]. HBV has been classified into 7 genotypes from A to G based on a sequence divergence of 8% or greater of the entire genome sequences[2-5]. The genotypes of HBV have distinct geographical distributions, which have been associated with anthropologic history[6,7].

Recently, genotypes of HBV have been reported to be an influential factor in the clinical manifestation of chronic liver disease in the host. Genotype A is associated with chronic liver disease more frequently than genotype D in Europe[8]. Genotype C induces more severe liver disease than genotype B found in Asia[9,10]. Furthermore, it was reported that genotype B had two subgroups[11], and these subgroups influence the clinical manifestations of liver disease in these patients[12].

Hawaii has a large Asian American and Pacific Islander population. Many people have emigrated from various countries in Asia and the Pacific Basin, where HBV infection is endemic. Indeed, the estimated rate of HBV carriers in Hawaii ranges from 1.7% to 3%[13,14], higher than 0.5% of the mainland of United States. However, there has been no information on genotype distribution and sequences of HBV in multi-ethnic carriers in Hawaii.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the HBV genotypes among 61 multi-ethnic carriers in Hawaii by genetic method, and to determine the influences of HBV genotypes on the clinical characteristics.

A total of 61 serum samples with HBsAg-positive were collected from patients with HBV infection who admitted St. Francis Medical Center in Honolulu, Hawaii between 1995 and 2000. All the patients were classified into 4 clinical groups: a symptomatic carriers (ASC) (n = 14) who had no subjective symptoms and had consistently normal serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels for at least 1 year, patients (n = 39) with chronic liver disease and persistently elevated serum ALT levels, such as those with chronic hepatitis (CH); patients with liver cirrhosis (LC) (n = 4), and patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (n = 4). A clinical diagnosis was made on the basis of serum biochemical examination, ultrasonography, computerized tomography and liver biopsy performed as required. Patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus were excluded. No patients received antiviral treatment during the follow-up period. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of the participating institutions in accordance with the 1975 Declaration in Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to any study related procedures.

The serum samples were stored at -20 °C until assay was performed. Serum DNA was extracted from 100 µL of serum using a DNA extractor kit (Genome Science Laboratory, Fukushima, Japan). The genotypes of HBV were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (HBV GENOTYPE EIA, Institute of Immunology Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with monoclonal antibodies that are type-specific to epitope in the preS2-region product[15]. If the result of ELISA was indeterminate, the genotypes were detected by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), as previously described[16]. Genotype B was classified into 2 subgroups, “Ba” which has a recombinant sequence of genotype C in the precore/core region, or “Bj” which does not have it, by the method reported previously[12]. Genotype G of HBV was detected by PCR with hemi-nested primers deduced from the unique insertion of 36 nucleotides (nt) in the core gene that is specific to this genotype[17].

Three complete genomes and 61 core promoter/precore regions of HBV were amplified by polymerase chain reaction with several primer sets, as previously described[18]. Amplified HBV DNA fragments were sequenced directly by dideoxy sequencing using a Taq Dye Deoxy Terminator cycle sequencing kit with a fluorescent 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). These nucleotide sequences were deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under the accession numbers AB105172- AB105174.

The pairwise nucleotide sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL W program[19]. The genetic distances were calculated with the 6-parameter method, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method[20] using ODEN program (version 1.1.1)[21]. To confirm the reliability of the phylogenetic tree, bootstrap resampling tests were performed 1000 times. Reference sequences of HBV, shown as accession numbers, were obtained from the DDBJ/EMBL/ GenBank database.

Statistical differences were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test, the Fisher's exact probability test and the Student’s t-test where appropriate. Differences were considered significant for a P-value less than 0.05.

The distribution of HBV genotypes among 61 multi-ethnic carriers in Hawaii was 14(23.0%) for genotype A, 9(14.7%) for genotype B and 38(62.3%) for genotype C. All the 9 genotype B strains were found to be Ba that has a recombinant sequence of genotype C in precore/core region. Genotypes D, E, F and G were not found in this study.

Clinical and serological characteristics were compared among the patients infected with genotypes A, B and C (Table 1). Patients with HBV genotype A were of Filipino (n = 10), Caucasian (n = 3) and Polynesian (n = 1) ethnicities. Genotype B was found in patients of Chinese (n = 4), Taiwanese (n = 2), Vietnamese (n = 2), and Hawaiian/Chinese (n = 1) ethnicities. Genotype C was found in the patients whose ethnic backgrounds were various Asian (n = 33), Micronesian (n = 3), and Caucasian (n = 2). There were no significant differences in terms of the age, gender, serum AST, ALT, ALP, γ -GTP and the clinical stages of liver disease among them. The proportion of HBeAg positive-phenotype in patients with genotypes A, B and C was 57.1%, 33.3% and 68.4% respectively, with a significant difference observed between genotypes B and C (P < 0.05). HCC was found in 10.5% of patients with genotype C.

| Features | Genotype n(%) | ||||

| A (n = 14) | B (n = 9) | C (n = 38) | |||

| Age (mean±SD, yr) | 49.1±14.5 | 46.9±13.0 | 43.0±11.9 | ||

| Gender (male:female) | 10:4 | 4:5 | 21:17 | ||

| Race | Asian | Mainland Chinese | 0(0) | 5(33) | 10(67) |

| Philippine | 10(83) | 0(0) | 2(17) | ||

| Taiwanese | 0(0) | 2(50) | 2(50) | ||

| Hong Kong | 0(0) | 0(0) | 8(100) | ||

| Vietnamese | 0(0) | 2(40) | 3(60) | ||

| Korean | 0(0) | 0(0) | 7(100) | ||

| Japanese | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(100) | ||

| Micronesian | 0(0) | 0(0) | 3(100) | ||

| Polynesian | 1(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | ||

| Caucasian | 3(60) | 0(0) | 2(40) | ||

| Liver disease | ASC | 2(14) | 3(33) | 9(24) | |

| CH | 10(71) | 5(56) | 24(63) | ||

| LC | 2(14) | 1(11) | 1(3) | ||

| HCC | 0(0) | 0(0) | 4(11) | ||

| HBeAg (+) | 8(57) | 3(33)a | 26(68)a | ||

| Laboratory finding | AST (U/L) | 63.3±42.2 | 56.6±58.7 | 54.7±81.9 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 41.4±31.6 | 34.8±27.0 | 37.3±59.7 | ||

| ALP (U/L) | 359.9±139.4 | 287.3±140.2 | 328.0±166.2 | ||

| γ -GTP (U/L) | 121.0±121.3 | 55.9±37.2 | 66.8±103.0 | ||

The frequency of mutation in core promoter (nt 1762/1764) and precore (nt 1858 and nt 1896) region was compared among genotypes A, B and C (Table 2). No significant differences in the frequency of the core promoter mutants were found among genotypes A, B and C (21.4%, 44.4%, and 57.9% respectively). Precore stop mutation (A-1896) was detected in genotypes B and C (33.3% and 21.1%) but not detected in genotype A. Sequence analysis of the mutation at nt 1858 in the precore region showed that all genotype B strains and 68% of genotype C strains possessed a T nucleotide (T-1858). In contrast, all genotype A strains had a C nucleotide in this region (C-1858).

| Mutation | Genotype n (%) | |||

| A (n = 14) | B (n = 9) | C (n = 38) | ||

| CP mutation | Double mutation | 3(21) | 4(44) | 22(58%) |

| PC mutation nt 1858 | Cytosine(C) | 14(100) | 0(0) | 12(32) |

| Thymine(T) | 0(0) | 9(100) | 26(68) | |

| nt 1896 | Guanine(G) | 14(100) | 6(67) | 30(79) |

| Adenine(A) | 0(0) | 3(33) | 8(21) | |

In order to clarify the significance of nucleotide variety (C or T) at nt 1858 in clinical and virological characteristics, 12 genotype C strains with C-1858 were compared to that of 26 strains of genotype C with T- 1858 (Table 3). All strains of both groups were obtained only from carriers whose ethnic background is Asian. HBeAg positive- phenotype was more frequent in genotype C patients with C-1858 than in those with T-1858 (83.3% vs 61.5%). The precore stop mutation (A- 1896) was found in 30.8%(8/26) of those with genotype C with nucleotide T-1858, but not in those subjects with the C-1858 nucleotide. There were no significant differences in frequencies in terms of the age, gender, serum AST, ALT, ALP, γ -GTP and the clinical stages of liver disease and BCP mutation between them.

| Mutation n(%) | |||

| C-1858 (n = 12) | T-1858 (n = 26) | ||

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 41.7 ± 13.0 | 43.5 ± 11.6 | |

| Gender (male:female) | 9:3 | 12:14 | |

| Race | Asian | ||

| Mainland Chinese | 3(30) | 7(70) | |

| Filipino | 0(0) | 2(100) | |

| Taiwanese | 0(0) | 2(100) | |

| Hong Kong | 3(38) | 5(63) | |

| Vietnamese | 2(67) | 1(33) | |

| Korean | 1(14) | 6(86) | |

| Japanese | 0(0) | 1(100) | |

| Micronesian | 2(100) | 0(0) | |

| Polynesian | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Caucasian | 1(50) | 1(50) | |

| Liver disease | ASC | 2(17) | 10(29) |

| CH | 8(67) | 21(60) | |

| LC | 1(8) | 1(3) | |

| HCC | 1(8) | 3(9) | |

| Laboratory finding | HBeAg (+) | 10(83) | 16(62) |

| AST (U/L) | 34.9 ± 17.0 | 63.8 ± 97.6 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 23.2 ± 11.2 | 43.8 ± 71.3 | |

| ALP (U/L) | 334.6 ± 186.3 | 324.9 ± 157.0 | |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 87.8 ± 167.3 | 57.2 ± 48.4 | |

| CP mutation | Double mutation | 6(50) | 16(62) |

| PC mutation | A-1896 | 0(0) | 8(31) |

To clarify the phylogenetic characterization of genotype C with C-1858, the complete genome of three HBV strains in carriers was sequenced. These subjects were from Micronesia (HI-1), Hong Kong (HI-2) and Vietnam (HI-3). Molecular evolutionary analysis was also conducted (Figure 1). Of them, one strain (HI-1) was clustered into a subgroup of genotype C with T-1858 from Polynesian with significant bootstrap values. The HI-2 and HI-3 strains were clustered into a subgroup of genotype C from Thailand and Vietnam, and separated from those strains of China and Japan. Moreover, the strains from Thailand and Vietnam had separate branches, and Hawaiian strains were clustered into the branch with Vietnam strains. Interestingly, all strains from Vietnam had C-1858, and those from Thailand had T-1858.

The findings of the present study indicate that HBV genotypes A, B and C are prevalent in Hawaii, and genotype C is the major genotype. Most cases of genotype A were found in immigrants from the Philippines and countries known to be prevalent regions for genotype A[6]. Genotype B was found only in immigrants from Asian regions where genotype B was endemic. In addition, genotype C was obtained from immigrant who came from various Asian countries, where genotype C was prevalent[22]. These results indicate that the distribution of HBV genotypes in Hawaii is associated with their respective ethnic background.

Recently, it was reported that genotype B could be classified into the Bj (j standing for Japan) and Ba (a standing for Asia) subgroups. Ba shared a genomic sequence with genotype C in the precore/core region, which was prevalent in Asian countries. Bj was restricted to Japan, and did not have this recombination[11]. It was shown that Ba induces more severe liver disease than Bj due to delayed seroconversion of HBeAg[12]. In this study, we found that genotype B, prevalent in Hawaii, was classified as Ba because they were all obtained from carriers with Asian ethnicity (excluding Japanese). In addition, the rate of positive HBeAg (33.3%) and basal core promoter (BCP) mutation (44.4%) in patients of Hawaii infected with genotype B were higher than those in Japanese patients with genotype B[9]. This result is also consistent with a previous report.

The double mutation in the core promoter, A-to-T mutation at nt 1762 and G-to-A mutation at nt 1764, was associated with reduced synthesis of precore mRNA [23,24]. In addition, it has been reported that the BCP mutation was associated with the progression of liver disease[25]. In this study, although it was not significant, BCP mutation was detected more frequently in genotype C than in genotype B. This result supports our previous observation that the BCP mutation was significantly more frequent in genotype C patients than in genotype B patients[9]. In addition, the present study demonstrated that the proportion of HBeAg positivity in genotype C was significantly higher than that in genotype B (68.4% vs 33.3%). However, our study could not show the clinical difference between genotypes B and C most likely due to the small number of patients studied. In the future, a case- controlled study in multi-ethnic carriers with larger samples is required to confirm if genotype C could induce more severe liver disease than genotype B[9,10].

Interestingly, we detected 12 strains of genotype C possessing C-1858 in Hawaii. HBV strain with C-1858 could prevent the A-1896 precore mutation from shutting off the synthesis of HBeAg[26] . This C-1858 variant was frequently found in genotypes A and F[26]. In genotype C, the C-1858 variant was observed in Southeast Asian patients, and the phylogenetic origin of genotype C with C- 1858 variant has been reported from Vietnam recently. In this study, the complete genomes of 3 genotype C strains with C-1858 were sequenced. One strain obtained from a Micronesian patient with C-1858 was clustered with previously reported Polynesian strains with T-1858. This indicates that both the C-1858 and T-1858 strains of genotype C are endemic to South Pacific countries. Two other strains obtained from patients with Hong Kong and Vietnamese ethnicities were clustered with the strains of genotype C from Southeast Asian countries. This result is consistent with geographic distribution of HBV genotype[18]. Interestingly, in this subgroup, there were 2 variants of strains, one had C-1858, prevalent in Vietnam, and the other had T-1858, prevalent in Thailand.

The clinical significance of C-1858 or T-1858 among genotype C is not well known. In this study, we compared the clinical and laboratory characteristics between C-1858 and T-1858 variant, but there were no significant differences between them. The number of patients was not enough to clarify the importance of this variation, and its significance for clinical characteristics remains unknown. Further studies would be required using larger numbers of samples.

In conclusion, genotypes A, B and C are the predominant types among multi -ethnic HBV carriers in Hawaii, and the distribution of these genotypes is dependent on the ethnic origin of the carriers in Hawaii. The influence of these genotypes on the clinical manifestations of these HBV carriers in Hawaii is not well defined due to the current small sample size. Case-controlled study with larger cohorts from our unique community is needed.

Edited by Wang XL and Chen WW Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733-1745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1728] [Cited by in RCA: 1712] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Sakugawa H, Sastrosoewignjo RI, Imai M, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Typing hepatitis B virus by homology in nucleotide sequence: comparison of surface antigen subtypes. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2575-2583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 725] [Cited by in RCA: 769] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Norder H, Hammas B, Löfdahl S, Couroucé AM, Magnius LO. Comparison of the amino acid sequences of nine different serotypes of hepatitis B surface antigen and genomic classification of the corresponding hepatitis B virus strains. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1201-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Norder H, Couroucé AM, Magnius LO. Complete genomes, phylogenetic relatedness, and structural proteins of six strains of the hepatitis B virus, four of which represent two new genotypes. Virology. 1994;198:489-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 587] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Van Geyt C, Zoulim F, Fried M, Schinazi RF, Rossau R. A new genotype of hepatitis B virus: complete genome and phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:67-74. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Norder H, Hammas B, Lee SD, Bile K, Couroucé AM, Mushahwar IK, Magnius LO. Genetic relatedness of hepatitis B viral strains of diverse geographical origin and natural variations in the primary structure of the surface antigen. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1341-1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Orito E, Ichida T, Sakugawa H, Sata M, Horiike N, Hino K, Okita K, Okanoue T, Iino S, Tanaka E. Geographic distribution of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype in patients with chronic HBV infection in Japan. Hepatology. 2001;34:590-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mayerat C, Mantegani A, Frei PC. Does hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype influence the clinical outcome of HBV infection. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:299-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Orito E, Mizokami M, Sakugawa H, Michitaka K, Ishikawa K, Ichida T, Okanoue T, Yotsuyanagi H, Iino S. A case-control study for clinical and molecular biological differences between hepatitis B viruses of genotypes B and C. Japan HBV Genotype Research Group. Hepatology. 2001;33:218-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B genotypes correlate with clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:554-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 684] [Cited by in RCA: 699] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sugauchi F, Orito E, Ichida T, Kato H, Sakugawa H, Kakumu S, Ishida T, Chutaputti A, Lai CL, Ueda R. Hepatitis B virus of genotype B with or without recombination with genotype C over the precore region plus the core gene. J Virol. 2002;76:5985-5992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sugauchi F, Orito E, Ichida T, Kato H, Sakugawa H, Kakumu S, Ishida T, Chutaputti A, Lai CL, Gish RG. Epidemiologic and virologic characteristics of hepatitis B virus genotype B having the recombination with genotype C. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:925-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ching N, Lumeng J, Pang R, Pang G, Or FW, Ching N, Ching C. Long-term low dose interferon alpha-2b in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B in multi-ethnic patients in Hawaii. Hawaii Med J. 1996;55:201-203. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Pon EW, Ren H, Margolis H, Zhao Z, Schatz GC, Diwan A. Hepatitis B virus infection in Honolulu students. Pediatrics. 1993;92:574-578. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Usuda S, Okamoto H, Iwanari H, Baba K, Tsuda F, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Serological detection of hepatitis B virus genotypes by ELISA with monoclonal antibodies to type-specific epitopes in the preS2-region product. J Virol Methods. 1999;80:97-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mizokami M, Nakano T, Orito E, Tanaka Y, Sakugawa H, Mukaide M, Robertson BH. Hepatitis B virus genotype assignment using restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns. FEBS Lett. 1999;450:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kato H, Orito E, Sugauchi F, Ueda R, Gish RG, Usuda S, Miyakawa Y, Mizokami M. Determination of hepatitis B virus genotype G by polymerase chain reaction with hemi-nested primers. J Virol Methods. 2001;98:153-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sugauchi F, Mizokami M, Orito E, Ohno T, Kato H, Suzuki S, Kimura Y, Ueda R, Butterworth LA, Cooksley WG. A novel variant genotype C of hepatitis B virus identified in isolates from Australian Aborigines: complete genome sequence and phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:883-892. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673-4680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47226] [Cited by in RCA: 45086] [Article Influence: 1454.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406-425. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ina Y. ODEN: a program package for molecular evolutionary analysis and database search of DNA and amino acid sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:11-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kao JH. Hepatitis B viral genotypes: clinical relevance and molecular characteristics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:643-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Akahane Y, Sugai Y, Yoshiba M, Moriyama K, Tanaka T, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Hepatitis B virus with mutations in the core promoter for an e antigen-negative phenotype in carriers with antibody to e antigen. J Virol. 1994;68:8102-8110. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Buckwold VE, Xu Z, Chen M, Yen TS, Ou JH. Effects of a naturally occurring mutation in the hepatitis B virus basal core promoter on precore gene expression and viral replication. J Virol. 1996;70:5845-5851. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Takahashi K, Aoyama K, Ohno N, Iwata K, Akahane Y, Baba K, Yoshizawa H, Mishiro S. The precore/core promoter mutant (T1762A1764) of hepatitis B virus: clinical significance and an easy method for detection. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:3159-3164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |