INTRODUCTION

Malignant bile duct strictures are mainly the result of cancer of the ampulla of Vater, pancreas, or bile duct, and account for most patients presenting with obstructive jaundice secondary to extra-hepatic bile duct stricture. Benign non-traumatic inflammatory strictures of the extra-hepatic bile duct are extremely rare with the exception of primary sclerosing cholangitis[1-3]. Most benign strictures reported in the literature are located in the hepatic hilum[4] or distal common bile duct (CBD). Here we report two cases of benign nontraumatic inflammatory strictures of the mid portion of the CBD with painless obstructive jaundice. They were confidently diagnosed as cholangiocarcinoma by radiological studies preoperatively.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

A 70 year-old male who had a 10-year history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus was presented to our hospital. He had tea-colored urine and yellowish skin discoloration for about 2 wk. No abdominal pain or body weight loss was reported. The physical examination was unremarkable except icteric sclera. A complete blood count was within normal limits.

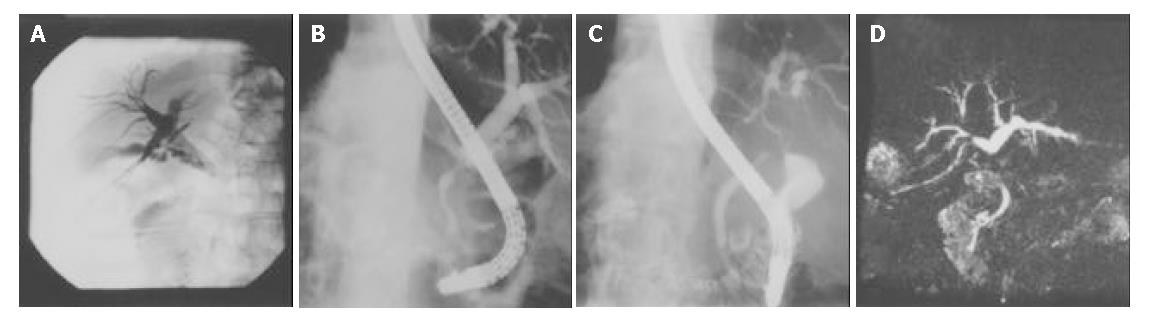

Serum total bilirubin/direct bilirubin (TB/DB) 5.6/2.9 mg/dL (normal 0.2-1.6/0-0.3 mg/dL), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 127 U/L (normal 0-40 U/L), asparate aminotransferase (AST) 78 U/L (normal 5-45 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALK-P) 380 U/L (normal 10-100 U/L) and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) 333 U/L (normal 8-60 U/L) were noted. Abdominal sonography showed dilatation of the intrahepatic ducts and CBD. The contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan disclosed similar findings. A PTCD tube was inserted and anterograde cholangiograms exhibited a segmental narrowing of the CBD about 2 cm below the insertion site of the cystic duct (Figure 1A). A segmental stricture about 1.5 cm in length over the CBD but below the cystic duct level and dilatation of the intrahepatic ducts were also demonstrated in the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram (ERCP) (Figure 1B). The pancreatogram was normal. Three sets of bile fluid cytology were negative. Tumor markers CA19-9 and CEA were not elevated. A diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma with CBD stricture was made. At surgery, stricture of the mid portion of the CBD was found. Cholecystectomy and choledocholithotomy with T-tube drainage were performed. Histological examination of the resected CBD showed chronic inflammation and fibrosis without malignant cells. No stone was detected in the gallbladder. Unfortunately, tea-colored urine and skin itching developed 3 years later. The laboratory evaluation revealed serum TB/DB 2.9/1.5 mg/dL, AST 111 U/L, ALT 125 U/L, ALK-P 427 U/L and γ-GT 676 U/L. Serum AMA, ASMA, IgG, IgM, IgA and ANA titers were within normal range. ERCP demonstrated segmental stricture of the common hepatic duct about 4 cm in length (Figure 1C) and choledochoduodenal fistula. The pancreatogram was normal. MR cholangiogram disclosed an annular mass lesion with enhancement at the proximal CBD, which caused segmental narrowing of the common hepatic duct and dilatation of the intrahepatic ducts (Figure 1D). Bile duct tumors such as cholangiocarcinoma were considered. At surgery, a firm and fixed tumor 4 cm × 3 cm in size at the CBD was palpated. The duodenal bulb was adhered to the tumor and a choledochoduodenal fistula was found. Segmental resection of the CBD, hepaticojejunostomy and enteroenterostomy, end-to-side, were performed. Histological examination of the resected CBD showed chronic cholangitis with focal atypical epithelium.

Figure 1 Segmental strictures of CBD demonstrated in percutaneous cholangiogram, ERCP and MR cholangiogram.

A: Segmen-tal narrowing of CBD below the insertion site of cystic duct in percutaneous cholangiogram; B: Segmental stricture of CBD with dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts demonstrated in ERCP; C: Segmental stricture of CHD demonstrated in ERCP; D: Segmental narrowing of CHD and dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts demonstrated in MR cholangiogram.

Case 2

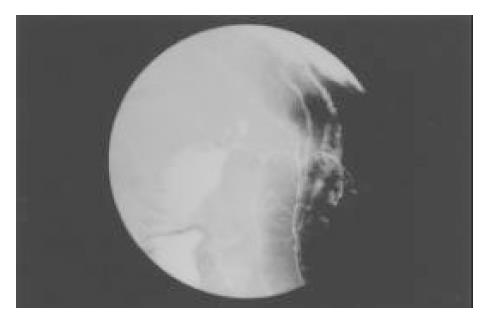

A 55 year-old male without significant past medical history was admitted because of painless jaundice for 1 mo. A double-contrast barium study of the upper gastrointestinal tract 2 years earlier demonstrated chronic duodenal ulcer with bulb deformity and prepyloric constriction (Figure 2). On examination, there was only icteric sclera. A complete blood count was within normal limits. Serum TB/DB 4.2/2.5 mg/dL, ALT 404 U/L, AST 293 U/L, ALK-P 357 and γ-GT 333 U/L were noted. Abdominal sonography showed dilatation of the intrahepatic ducts and CBD. A contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan disclosed dilatation of the intrahepatic ducts and proximal CBD associated with distention of the gallbladder. ERCP failed. The MRI revealed an annular lesion about 3.5 cm in length in the mid portion of the CBD (Figure 3). Three sets of bile fluid cytology were negative. Tumor markers CA19-9 and CEA were not elevated. A diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma was made. The patient had a laparotomy for resection of the tumor. A tumor over the middle third portion of the CBD with thickened wall was found. No stone was detected in the gallbladder or CBD. Resection of the tumor and Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy, end-to-side, was then performed. However, the postoperative histological examination of the lesion showed only chronic inflammation with marked fibrosis.

Figure 2 Chronic duodenal disease with bulb deformity and prepyloric constriction revealed in a double-contrast barium study.

Figure 3 Annular lesion in the mid portion of CBD disclosed in MRI (coronal view).

DISCUSSION

The clinical presentation and preoperative radiological studies without tissue or cytological proof led us to the diagnosis of malignant bile duct strictures in these 2 cases. It has been agreed that any localized extra-hepatic bile duct obstruction coexisting with intra-hepatic bile duct dilatation should be considered as malignancies such as cancer of the ampulla of Vater, pancreas, or bile duct (cholangiocarcinoma) until proven otherwise[5]. This agreement arose because of the difficulty in obtaining a tissue diagnosis in patients with obstructive jaundice caused by a bile duct stricture. Application of improved diagnostic methods, such as thin-section spiral CT and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, can potentially increase the diagnostic accuracy, but neither could reliably differentiate malignant from benign lesions[6,7]. Preoperative histological or cytological examination by means of biopsy or brush cytology was often difficult and liable to false-negative results with low sensitivity and could carry a potential risk of needle tract metastases[8-12]. The lack of a tissue or cytological evidence might result in some patients being inappropriately treated as malignant disease when a benign stricture was present and vice versa. In the study of Gerhards et al[4] a false-positive preoperative diagnosis of malignancy resulted in a 15% resection rate of benign lesions in patients with suspicious hilar strictures. Careful review of all preoperative information and radiological images of our 2 cases yielded the initial diagnosis of a CBD tumor, although post-operative pathological examination revealed only inflammation and fibrosis. The decision to undertake resection of the strictures in these 2 cases was therefore not an error of judgment. Obviously, resection of the lesion and obtaining a tissue diagnosis are still the most reliable way to rule out malignancy. Therefore, resection of a benign stricture mimicking a malignant stricture in the extra-hepatic bile duct cannot be avoided completely. However, the lack of clinical constitutional symptoms such as body weight loss or abdominal pain and elevated tumor markers may implicate the possible benign entity of the disorder.

Benign, single, non-traumatic inflammatory strictures of the biliary tracts were infrequently reported with the exception of primary sclerosing cholangitis[1-3]. Indeed, many benign nontraumatic inflammatory strictures of the common bile duct have been generally considered to be a variant of primary sclerosing cholangitis although Standfield et al[13] described 12 cases of benign strictures of unknown etiology, and differentiated them from the localized form of sclerosing cholangitis. Other inflammatory conditions of the CBD which are potential etiological factors included bacteria or virus infection, parasite infestation, abdominal trauma, congenital abnormality[14], chronic pancreatitis[15], inflammatory pseudotumors[16], complication of chemotherapy[17], complication of duodenal ulcer disease[18-20], and sclerosing therapy of bleeding duodenal ulcer[21]. Most benign segmental strictures of the extra-hepatic bile duct reported in the literature were located at the hilum or distal CBD. Few cases in the mid CBD have been reported.

The CBD strictures of these 2 patients were less likely due to biliary duct stones because the radiological studies and operative findings did not show the existence of stones. The normal pancreatogram excluded the possibility of chronic pancreatitis as the cause of mid CBD strictures. The radiological appearance, histological examination and the extremely rare incidence in this area made the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis less likely.

According to the clinical history and surgical findings, stricture of the CBD owing to fibrous encasement by chronic inflammatory changes due to an adjacent duodenal ulcer in these 2 cases was considered. Duodenal ulcer disease is a common disorder, and its associated complications such as hemorrhage, gastric outlet obstruction and perforation, are well known. However, the biliary complications of duodenal ulcer disease, such as biliary-enteric fistula or partial obstruction of the CBD were rare and less well-known[18-20], especially after the worldwide use of effective antisecretory agents, H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors.

In conclusion, benign non-traumatic inflammatory strictures affecting the common bile duct can be mistaken for malignant tumors. Their existence should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any biliary strictures. The radiological documentation of these 2 cases is of interest to draw attention to the rare complication of obstructive jaundice secondary to duodenal ulcer disease. A tissue diagnosis should be obtained whenever possible as radiology alone is often insufficient to make a firm diagnosis of malignancy in biliary strictures.