Copyright

©The Author(s) 2021.

World J Gastroenterol. Mar 28, 2021; 27(12): 1132-1148

Published online Mar 28, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i12.1132

Published online Mar 28, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i12.1132

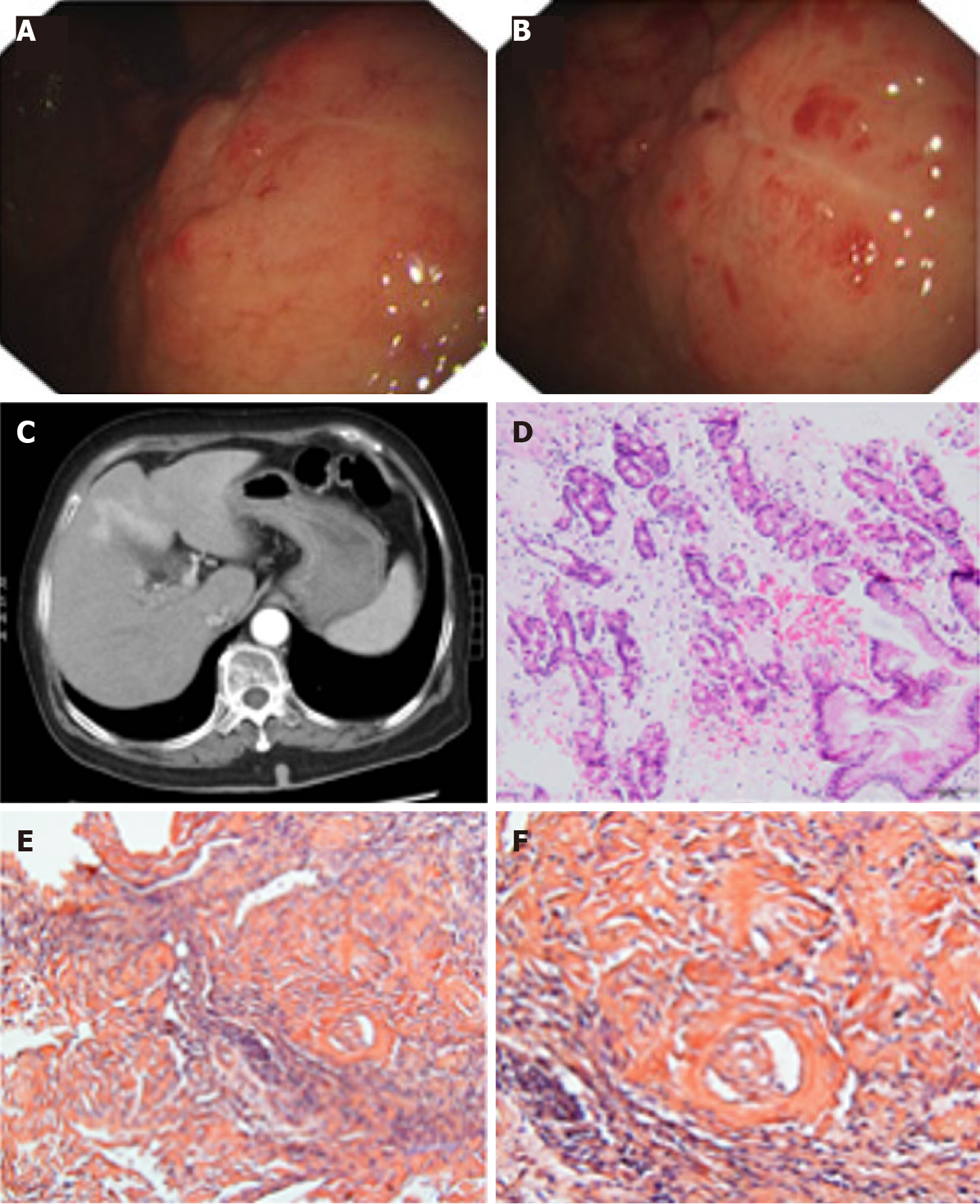

Figure 1 Pathological findings from a 70-year-old woman with localized gastric amyloidosis.

The patient came to the hospital with a chief complaint of hematemesis for 2 wk. A and B: Endoscopic findings show multiple congested fragile ulcers scattered in the gastric body and fundus. A 4.0 cm × 4.0 cm area of the mucosa with edema, ulcers, and poorly delineated boundaries was observed in the anterior wall of the gastric body and fundus. The lesion appeared as a rough, congested area with edema, localized superficial fragile ulcers and active bleeding. Spot-like congested erosions exhibited a scattered distribution in the mucus of the sinus; C: CT reflected diffusely thickened gastric walls and shallow folds of the mucosa, while no abnormalities were observed in the enhanced images; D: H&E staining revealed massive amyloid fibrous connective tissues deposited in the interstitium with inflammatory cell infiltration; E and F: Congo red staining confirmed the existence of the amyloid protein (E: Congo red, × 200 magnification; F: Congo red, × 400 magnification).

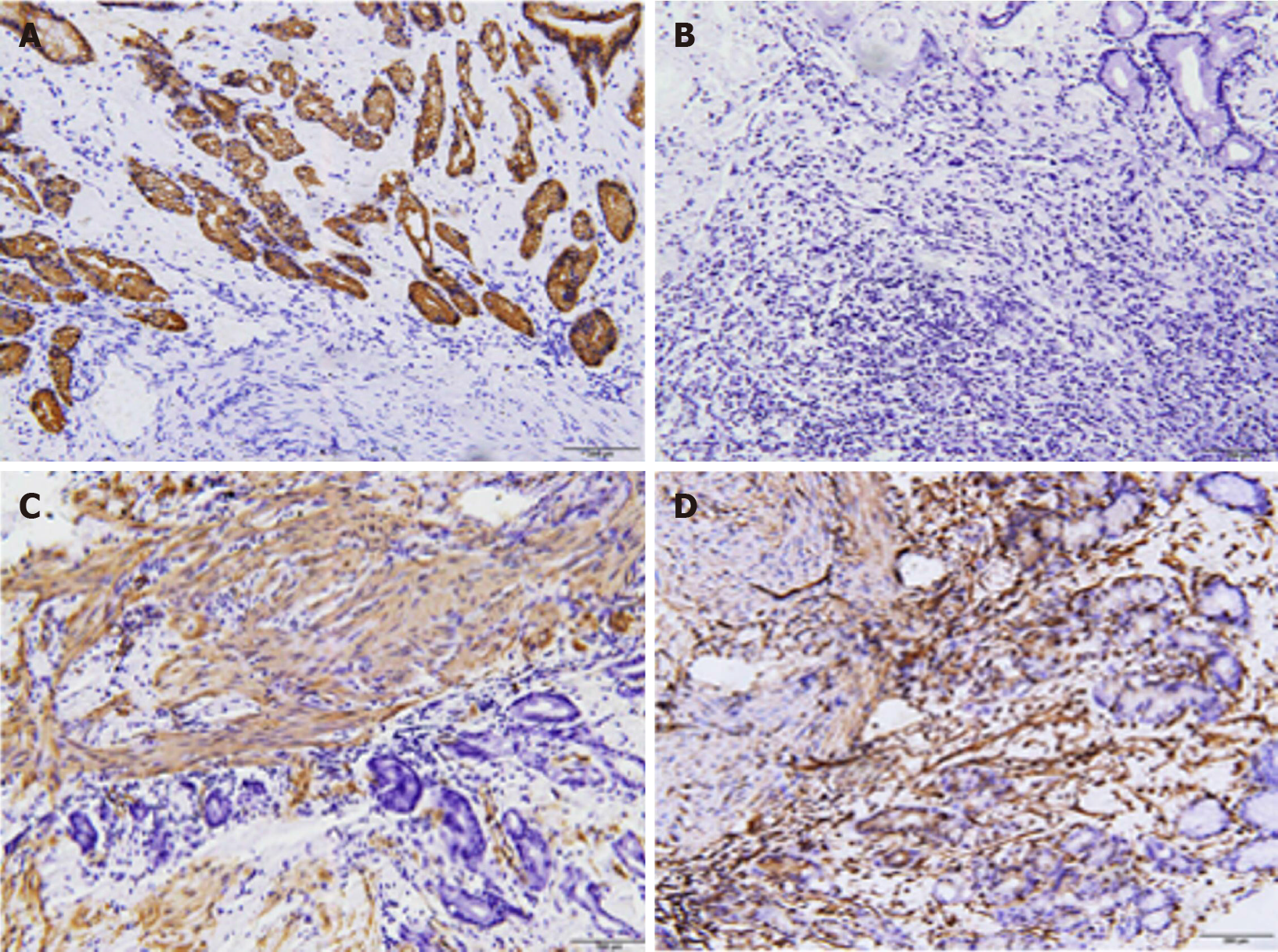

Figure 2 Results of immunochemical staining using several antibodies excluded the diagnosis of gastric cancer.

A: CKPAN-positive staining in the glands; B: Periodic Acid-Schiff staining is negative; C: Smooth muscle actin-positive staining in the muscularis mucosa; D: Vimentin-positive staining.

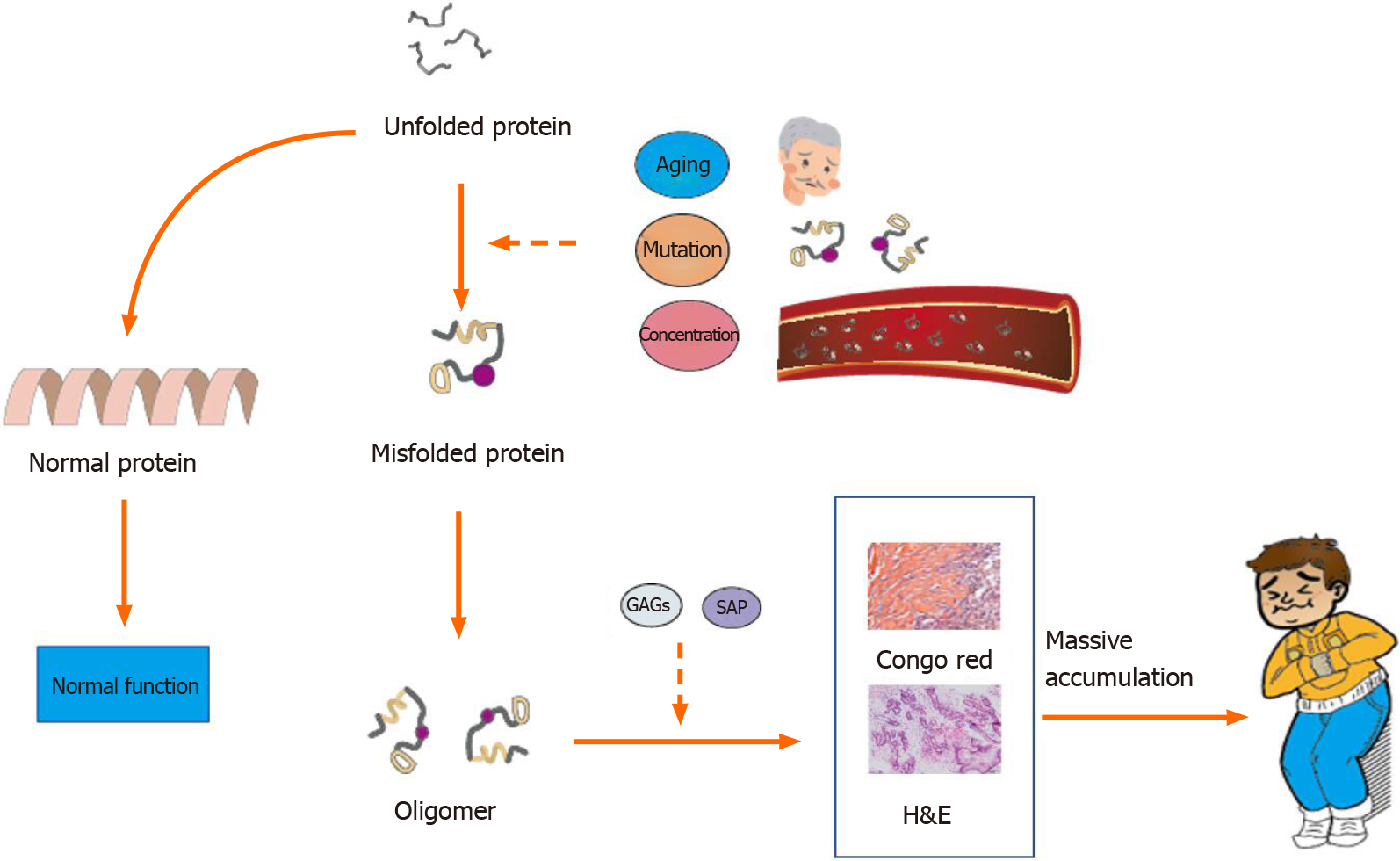

Figure 3 Potential molecular events leading to amyloidosis.

Without intervention, the unfolded protein becomes the normal protein. Factors such as aging, mutation, and high blood concentrations may cause protein misfolding. The misfolded protein aggregates into oligomers and forms fibrils with the assistance of glycosaminoglycans and serum amyloid P. Massive deposition of amyloid fibrils leads to amyloidosis. GAGs: Glycosaminoglycans; SAP: Serum amyloid P.

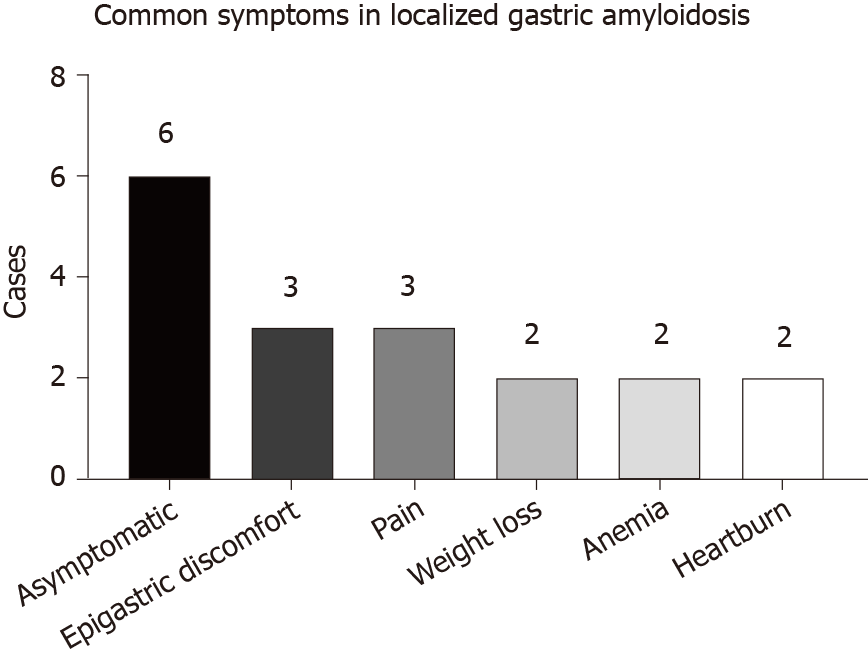

Figure 4

Common symptoms described in case reports of localized gastric amyloidosis and the present times.

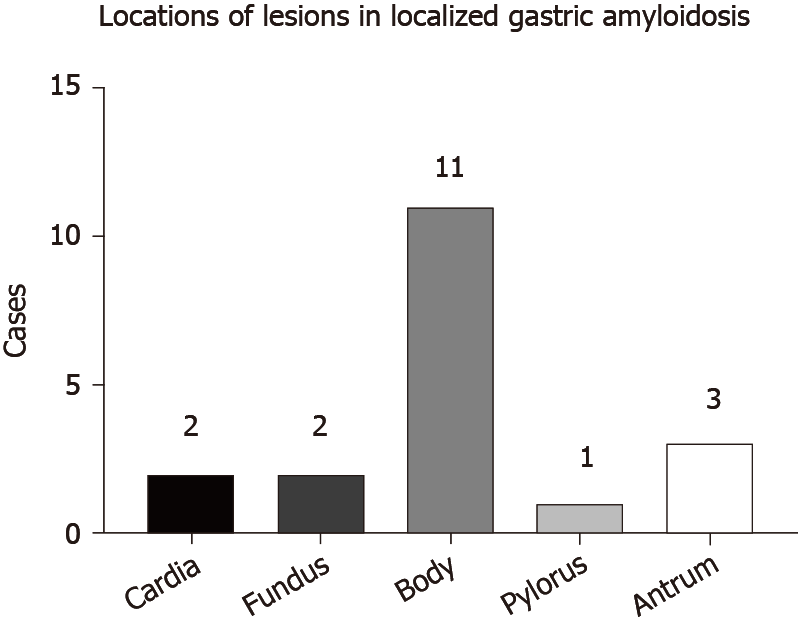

Figure 5

Common lesion locations of amyloid deposition in localized gastric amyloidosis and the present times.

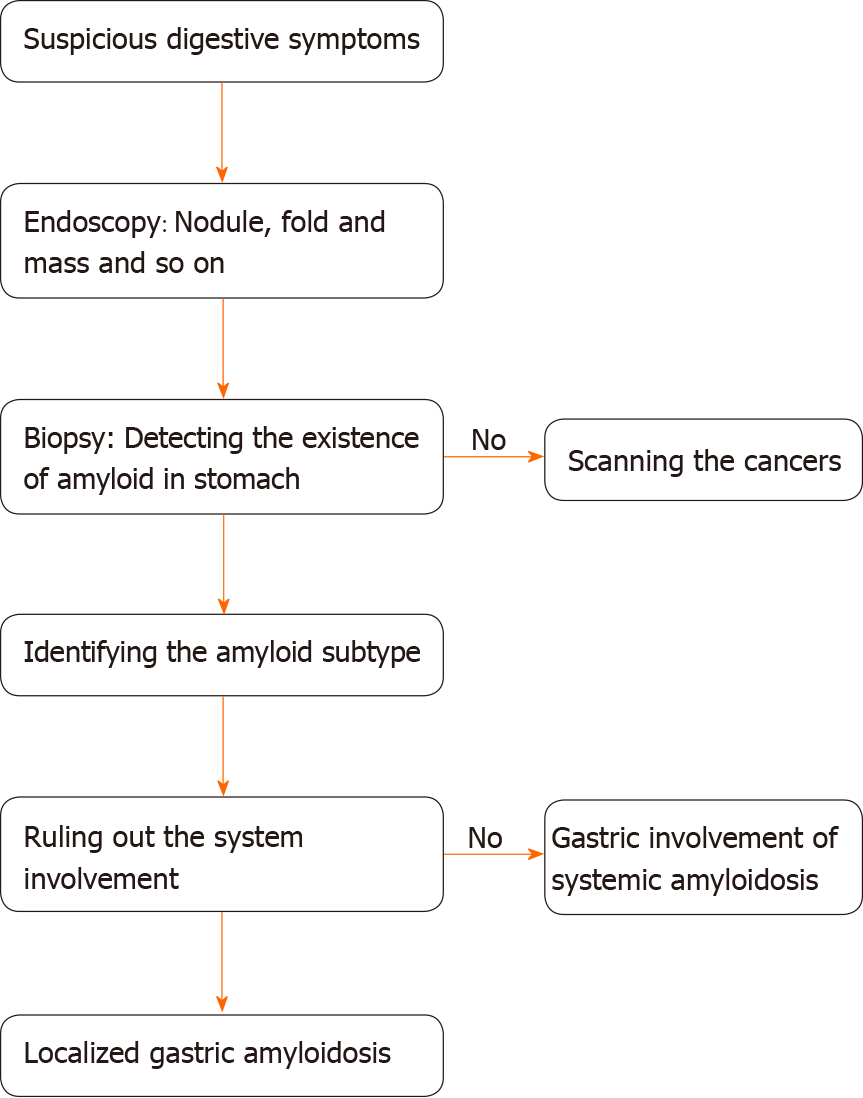

Figure 6 A diagnostic procedure from the perspective of clinicians.

When a patient arrives at the hospital with suspected digestive symptoms, clinicians should initially perform endoscopy. Relevant endoscopic manifestations should lead to a biopsy examination to detect the existence of amyloid using Congo red staining. If a negative result is obtained, a screen for cancers is recommended, given the resemblance of their clinical manifestations. For a positive result, clinicians should identify the amyloid protein subtype. Then, a series of tests must be chosen by clinicians according to the patient’ conditions to exclude the systemic involvement of amyloidosis. Finally, a diagnosis of localized gastric amyloidosis is determined.

- Citation: Lin XY, Pan D, Sang LX, Chang B. Primary localized gastric amyloidosis: A scoping review of the literature from clinical presentations to prognosis . World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(12): 1132-1148

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i12/1132.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i12.1132