Published online Dec 29, 2023. doi: 10.5315/wjh.v10.i4.42

Peer-review started: October 3, 2023

First decision: November 2, 2023

Revised: November 15, 2023

Accepted: December 19, 2023

Article in press: December 19, 2023

Published online: December 29, 2023

Processing time: 86 Days and 4 Hours

Extramedullary blast crisis in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is an uncommon occurrence of leukemic blast infiltration in regions other than the bone marrow. Malignant infiltration of the serosal membranes should be considered in cases where CML presents with ascites or pleural effusion.

A 23-year-old female with CML presented with progressively worsening ascites and pleural effusion despite first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. Her blood work indicated leukocytosis with myelocyte bulge and 2% blasts. Analysis of the patient’s bone marrow confirmed the chronic phase of CML. Abdominal ultrasound revealed hepatosplenomegaly with ascites. The fluid investigation of both ascites and pleural effusion revealed a predominance of neutrophils with exudate. However, no acid-fast bacilli or growth was observed after culturing. Although hydroxyurea reduced cell counts, there was no observed effect on ascites or pleural effusion. Repeat investigation of the ascitic and pleural fluid revealed a polymorphous myeloid cell population consisting of myelocytes, metamyelocytes, band forms, neutrophils and a few myeloblasts. Extramedullary blast crisis was suspected, and mutation analysis was performed. We switched the patient to dasatinib. The patient’s symptoms were relieved, and ascites and pleural effusion diminished.

Serosal membrane involvement in CML is extremely rare. In this case, the patient responded well to dasatinib treatment.

Core Tip: Extramedullary blast crises exhibit diverse presentations, underscoring the importance of awareness of possible sites of occurrence. In cases of chronic myeloid leukemia with ascites or pleural effusion, it is essential to consider the possibility of malignant infiltration of serosal membranes as a potential diagnosis. Recognizing these signs early can lead to timely intervention and management.

- Citation: Mishra R, Garg S, Bharti P, Malla DR, Rohatgi I, Gautam S. Unusual presentation of extramedullary blast crisis in chronic myeloid leukemia: A case report. World J Hematol 2023; 10(4): 42-47

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6204/full/v10/i4/42.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5315/wjh.v10.i4.42

Extramedullary blast crisis (EBC) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is an uncommon occurrence of leukemic blast infiltration in regions other than the bone marrow. The most prevalent site of involvement in EBC is the lymph nodes, followed by the bone and skin[1]. Serosal membrane involvement is exceedingly uncommon in CML. Currently, there are only a few case reports describing pleural effusion and ascites in CML. Herein, we described a patient with CML treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy who developed EBC with concomitant ascites and pleural effusion.

A 23-year-old female presented to our hospital with the chief complaint of progressive distension of the abdomen. The patient also experienced swelling of the legs for 2 mo prior to presentation and right-sided chest pain that increased during inspiration.

The patient experienced nonspecific malaise, growing weariness, and anorexia for 2 wk prior to presentation.

The patient had been diagnosed with CML 3 years prior to presentation and was under imatinib therapy (600 mg once a day). The patient had been regular with her treatment regimen and was symptomatically better until the time she started having these symptoms.

There was no history of similar illnesses in the patient’s family.

The patient was afebrile with normal vitals. She had pallor and bilateral pitting pedal edema that extended above her ankles. An evaluation of the respiratory system indicated a dull note with reduced breath sounds at the right infraaxillary and infrascapular areas. Abdominal examination revealed tense ascites and splenomegaly extending up to the umbilicus.

Initial laboratory investigations revealed that the patient was anemic with hemoglobin of 8.9 g/dL (normal range: 12-15 g/dL). It also revealed leukocytosis with white blood cell counts of 68000 (P68/L24/B4/E2) and thrombocytosis with platelets of 600000. Hyperkalemia (5.7 mmol/L; normal range: 3.5-5.5 mmol/L), hyperphosphatemia (6.9 mg/dL; normal range: 2.5-4.5 mg/dL) and elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels (572 IU/L; normal range: 105-270) were also observed. Findings for liver and renal function tests, coagulation profile and serum procalcitonin level were all normal.

Thoracocentesis was performed under ultrasound guidance, and the aspirated fluid was exudative (protein 5.3 g/dL; normal range: 1.5 g/dL) along with 600 cells/mm3 with polymorphic preponderance (normal range: < 5 cells/mm3). The serum ascites albumin gradient level in the ascitic fluid was 0.9, and the cytobiochemical profile was comparable (300 cells/mm3; normal range: < 5 cells/mm3; protein 5.1 g/dL; normal range: 1.5 g/dL). In pleural and ascitic fluid, the adenosine deaminase levels were 4.3 U/L and 8.1 U/L, respectively (normal range: < 40 U/L). There were no pathogenic organisms or acid-fast bacilli found in pleural and ascitic fluid cultures.

The peripheral smear showed leukocytosis with myeloid bulge and bimodal myeloid population. Both mature and immature myeloid proliferation with 2% blasts (normal range: < 5% blasts) were observed. Myelocytes made up 13% of the myelogram. Metamyelocytes and band formations were 16% and 5%, respectively. An impression of CML in the chronic phase was reported. The neutrophil alkaline phosphatase score was 24 (normal range: 20-150). The Mantoux, viral markers, thyroid function test and autoimmune profile findings were unremarkable, while blood and urine cultures showed no growth. The levels of tumor markers carbohydrate antigen 125, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were within normal limits. A myelogram comparable to the peripheral smear was seen in the bone marrow aspirate, with 2% blasts. The biopsy revealed CML in the chronic phase with fibrosis (World Health Organization grade 2) and limited collection of blasts.

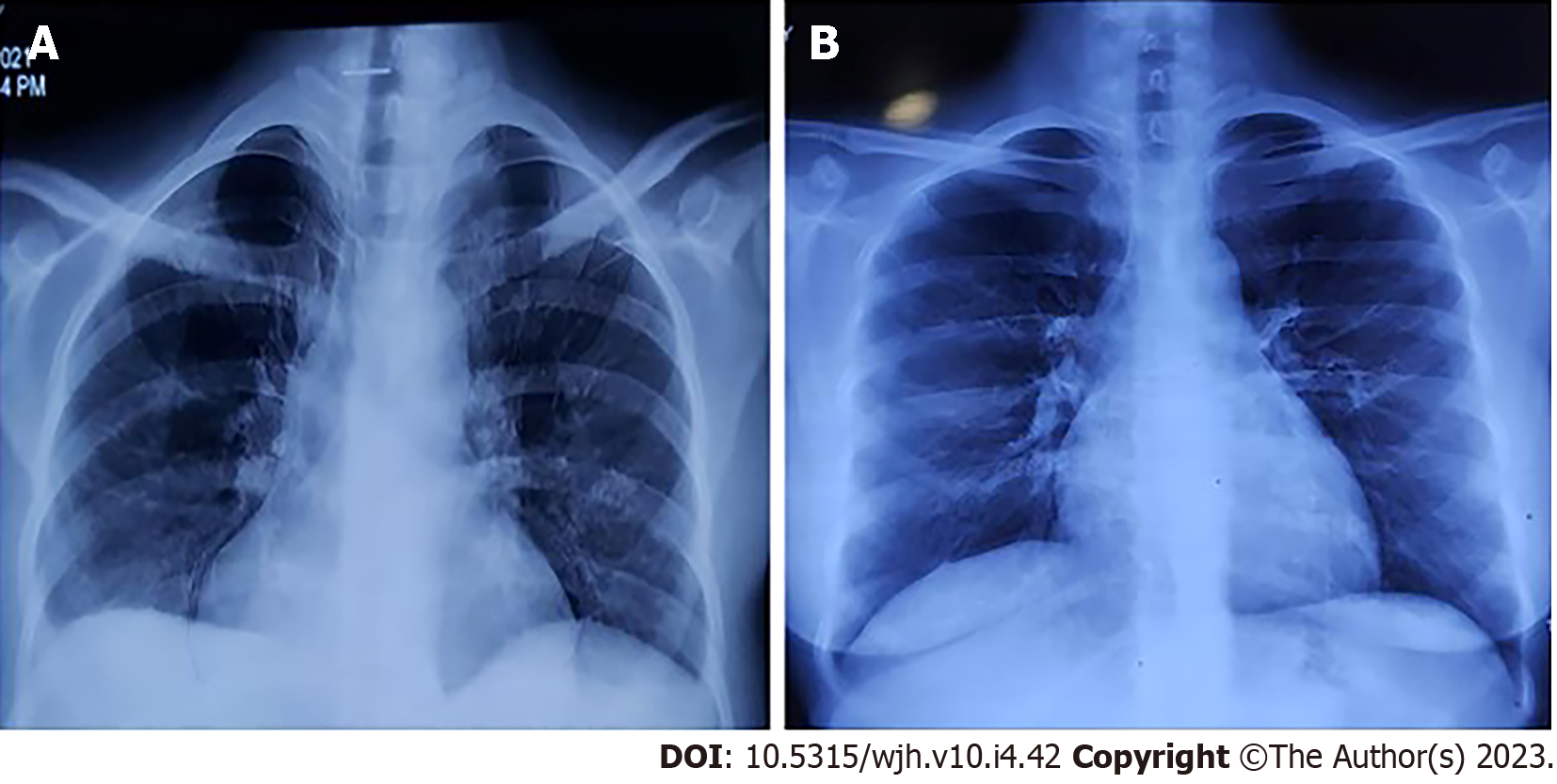

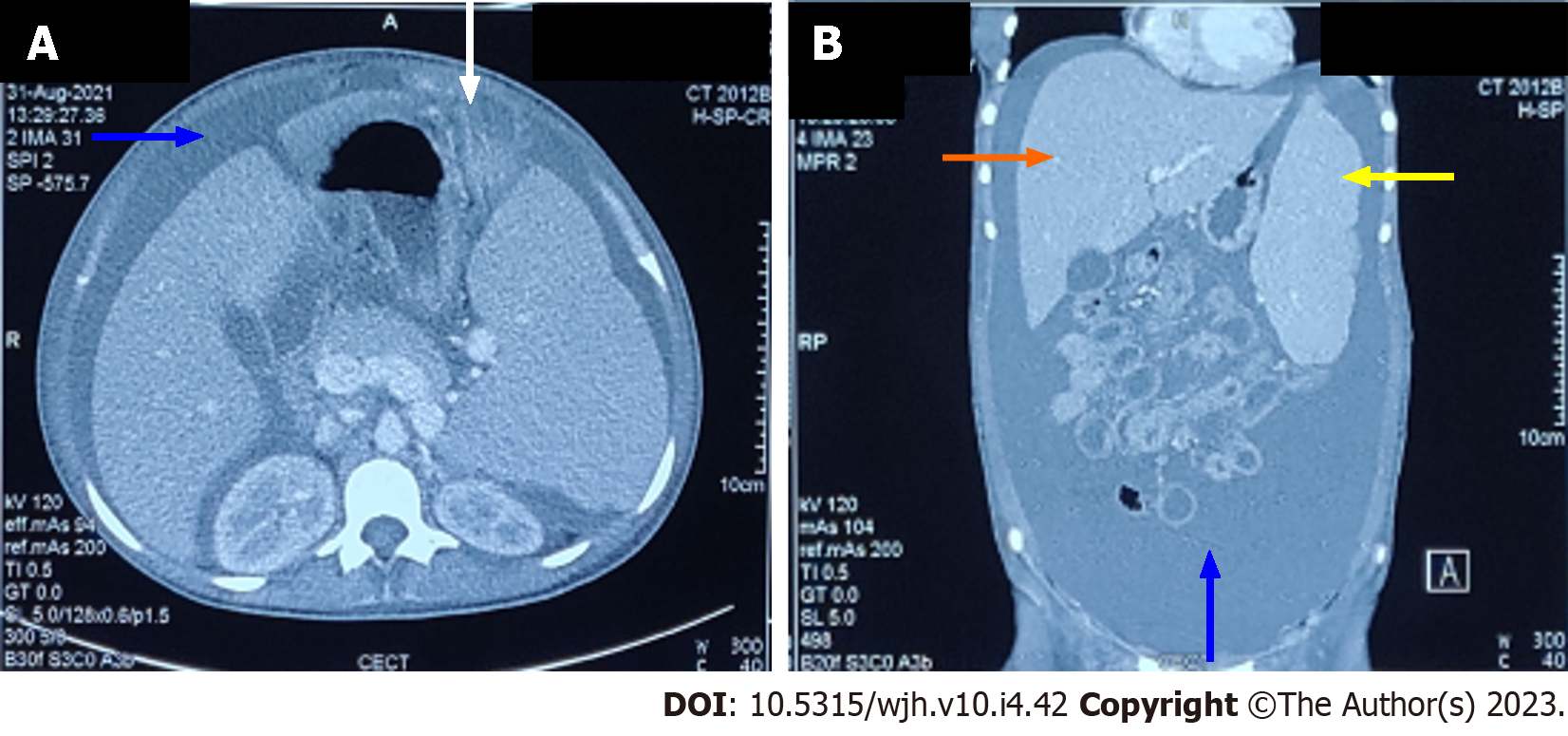

The chest X-ray (Figure 1A) confirmed pleural effusion (right > left), while the ultrasound revealed hepatosplenomegaly with ascites. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (Figure 2) confirmed the sonographic findings, revealing smooth enhancing peritoneum with omental caking. Computed tomography ruled out any mass or space-occupying lesions. Two-dimensional echocardiography was suggestive of mild pericardial effusion with normal ejection fraction.

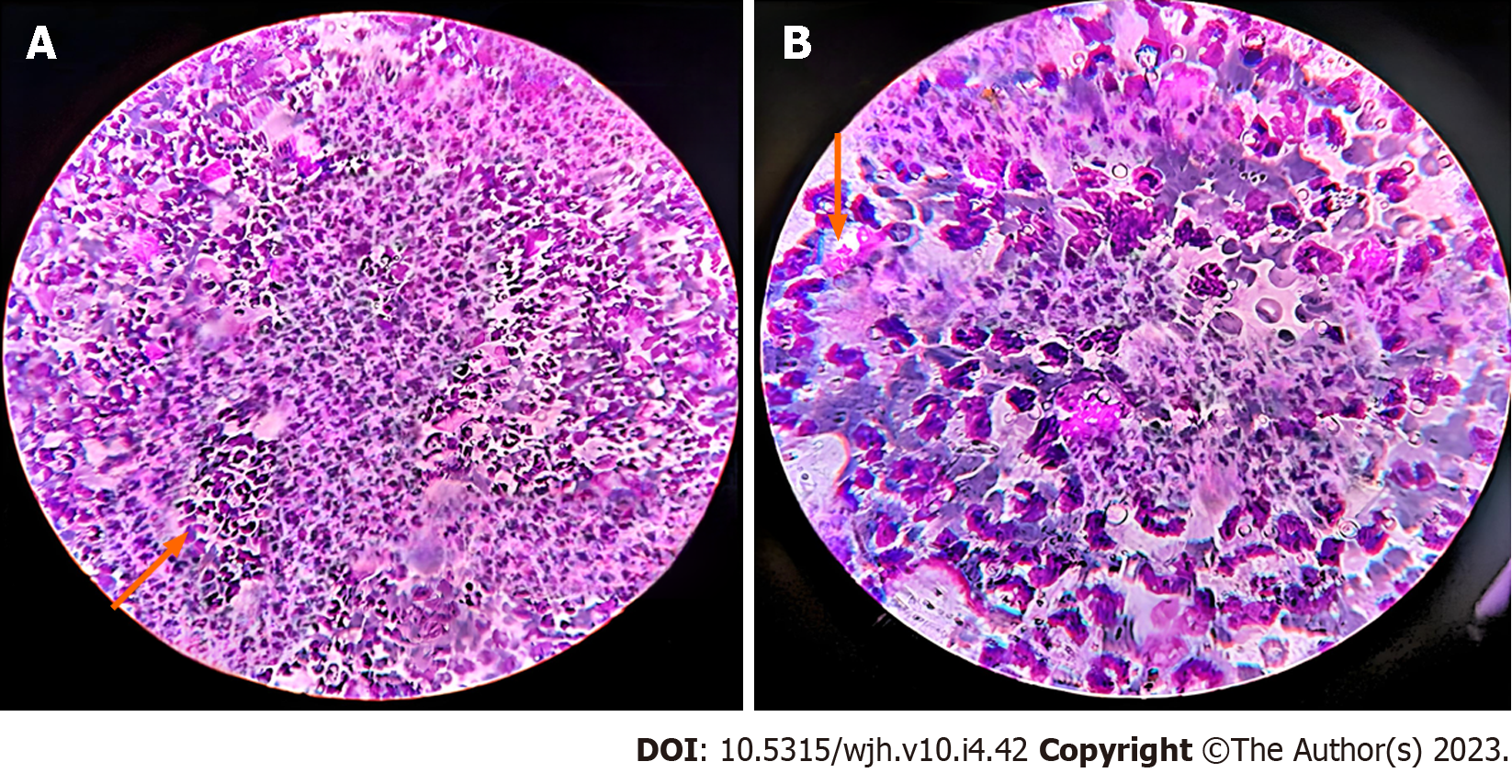

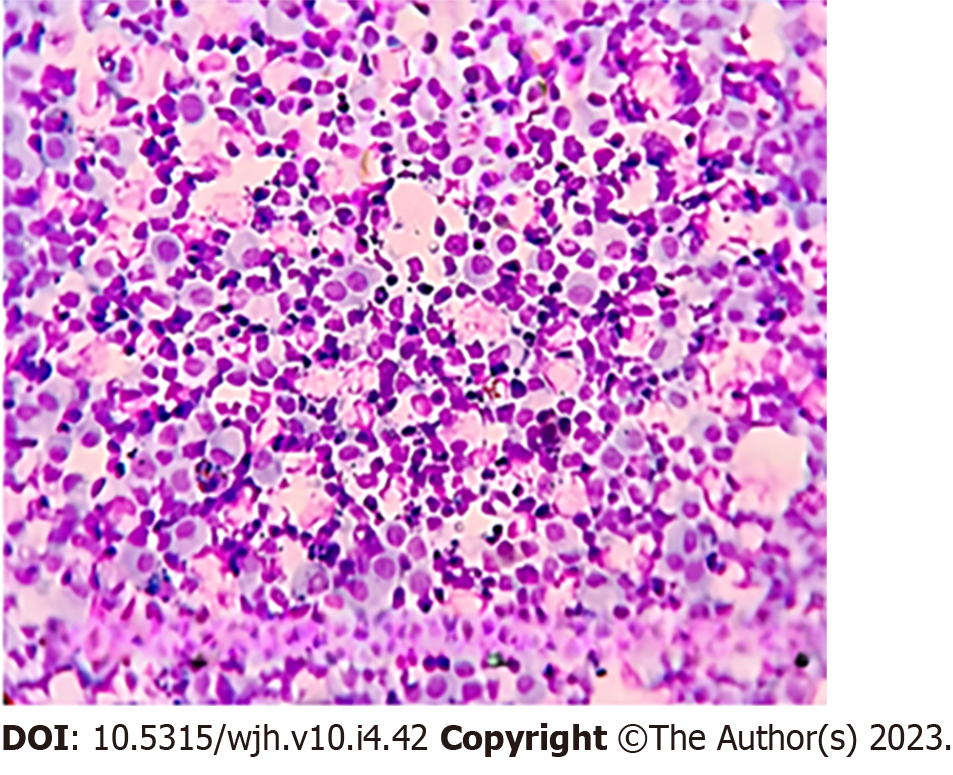

Ascitic fluid was sent for smear testing, which revealed the presence of malignant cells. It possessed a polymorphous myeloid cell population that included myelocytes, metamyelocytes, band forms, neutrophils, and a few myeloblasts. Analysis of the pleural effusion identified several kinds of myeloid cells (Figures 3 and 4). We diagnosed the patient with EBC in the form of ascites and pleural effusion.

We initially treated the patient with hydroxyurea. This treatment reduced cell counts, but the patient’s symptoms were not relieved. Since the patient was receiving imatinib treatment, mutation analysis was performed. We identified a G250E mutation in the BCR-ABL protein. We recommended dasatinib (100 mg once a day) and a stem cell transplantation. The patient consented to dasatinib treatment but declined the stem cell transplantation treatment.

The peripheral smear was repeated 1 mo after switching to dasatinib treatment. No immature myeloid cells were observed. Chest X-ray (Figure 1B) and abdominal ultrasound 3 mo after beginning the dasatinib treatment revealed that the pleural effusion and ascites had disappeared. We also observed that the spleen shrank to 12 cm. The patient’s symptoms were also relieved, and her overall health had improved. She continued dasatinib treatment without any significant side effects.

Blast crisis in CML is classified according to the place of origin (medullary or extramedullary) and cell type (myeloid, lymphoid, or mixed). At least one of the following[2] characterises the CML blast crisis: (1) 20% myeloblasts or lymphoblasts in blood or bone marrow; (2) Large clusters of blast cells in bone marrow biopsies; or (3) The emergence of chloroma.

EBC is widely recognized in CML and is present in 8%-15% of patients over the course of the illness[3,4]. EBC often manifests as a tumorous mass known as a chloroma. However, it can also manifest as a diffuse infiltrate. Lymph nodes (40%–61% of cases) are the most common location of extramedullary disease, followed by bone (22%-37% of cases) and skin or soft tissues (20%)[5]. Hepatosplenomegaly is not considered EBC in CML patients. EBC is particularly common during the accelerated phase of CML or during the blast crisis. Extramedullary disease in CML is an indicator of poor prognosis and indicate a change in therapy usually reserved for blast crisis treatment[6].

Serosal membrane involvement in CML is extremely rare. Aleem and Siddiqui[4] described a patient in the chronic phase of CML who presented with massive ascites. They postulated that the cause was mesenteric/peritoneal infiltration. The response to imatinib was outstanding, with a full cytogenetic response and complete elimination of ascites. Likewise, Deshpande et al[7] reported a case of CML with extramedullary illness manifesting as tense ascites. Both the ascitic fluid and a peripheral blood smear included all phases of granulocytes and a few blast cells. A favorable response was reported after imatinib therapy. Ridha et al[8] described a CML patient who developed pleural effusion during imatinib therapy. A diagnosis of EBC in the form of pleural effusion was established based on cytological investigation of the pleural fluid, which revealed cells with the morphological hallmarks of myeloblasts. The patient continued to receive imatinib but died after 1 mo. Nuwal et al[6] described a case of a 26-year-old male with CML who presented with pleural effusion as the initial clinical symptom.

The mechanism of pleural effusion in CML patients is unknown. However, several hypotheses exist. The first includes leukemic infiltration into the pleura that frequently occurs during or soon before bone marrow progression to the blast crisis phase. The lymph nodes, bone, and nervous system are the most affected locations, with infiltration of the brain, testis, skin, breast, soft tissue, synovial, gastrointestinal tract, ovaries, kidneys, and pleura occurring less frequently. Pleural involvement has been infrequent, and isolated pleural blast crises in the absence of medullary change are extremely unusual.

Extramedullary hematopoiesis is another probable source of pleural effusion in CML, albeit the pleura is an uncommon location for this process. Extramedullary hematopoiesis, as opposed to pleural leukemic infiltration, contains hematopoietic cells of the erythroid, myeloid and megakaryocytic types.

Pleural effusions in CML can also be caused by blockage of pleural capillaries or penetration of interstitial tissue by leukemic cells during uncontrolled leukocytosis and enhanced capillary permeability owing to cytokine release. Predisposing variables including leukostasis and platelet dysfunction may play a role in CML hemorrhagic effusion.

Non-malignant causes of effusion have also been proposed. This would include infection and hypoproteinemia. As a result, this cause must be confirmed by blood investigations using a specific stain to identify bacteria and/or the presence of necrotic material.

Drug-induced pleural effusion is another probable cause of pleural effusion in CML. Dasatinib and imatinib are tyrosine kinase inhibitors that are efficacious in treating CML patients. The pathogenesis remains unclear. However, off-target tyrosine kinase inhibitors may influence the immune system.

The mechanism of ascites in CML may be similar to the presence of pleural effusion in CML but has not been investigated due to the rarity of this type of occurrence. Despite our extensive literature search, we did not find another published case in which the patient presented with concomitant ascites and pleural effusion as EBC in a case of CML. Moreover, our patient was already receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

The basic objective of CML blast crisis treatment is to return to the chronic phase. Once the patient is in the chronic phase, it is recommended that the patient should proceed with an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Treatment varies according to the blast lineage [i.e. myeloid (70%) vs lymphoid (30%)][10,11].

Administration of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (with or without chemotherapy) followed by an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is the chosen treatment in myeloid crisis. According to studies, treating de novo myeloid blast crisis with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor alone and then assessing the response is recommended. In cases where the myeloid blast crisis occurs during tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment, the recommended treatment is acute myeloid leukemia-type induction chemotherapy in combination with a more potent tyrosine kinase inhibitor[10,11].

In the case of our patient, we switched to a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor based on mutation analysis. The patient had a favorable response. Patients who are receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment are more likely to experience lymphoid blast crisis[11]. Transition to a second-generation or third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor is required for these individuals. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be used alone or in conjunction with lower-intensity chemotherapy.

There is a lack of data on which TKI should be utilized as the first-line treatment for patients experiencing a blast crisis. It is also unknown whether the treatment should be different if the patient is a candidate for a hematopoietic cell transplant. In general, treatment with a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor (e.g., dasatinib, nilotinib) is re-commended. If the disease progression/blast crisis occurs while the patient is receiving imatinib for early stage CML, second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors should be administered. Ponatinib can also be recommended if the progression occurred while the patient was on dasatinib, nilotinib or bosutinib.

The limitations of our case included a lack of adequate clinical investigations (no genetic tests were performed) at the time of the first diagnosis as well as the failure to obtain evidence of chloroma on the ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of the omentum.

EBC can manifest in a number of ways in a variety of locations. It is critical for clinicians to be aware of potential sites of presentation. Serosal involvement in CML is rare, and concurrent involvement of the peritoneum and pleura has not been described previously. Investigation for malignant cells in the fluid should be performed in CML patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Hematology

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu C, China S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Sahu KK, Malhotra P, Uthamalingam P, Prakash G, Bal A, Varma N, Varma SC. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia with Extramedullary Blast Crisis: Two Unusual Sites with Review of Literature. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2016;32:89-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cortes J, Pavlovsky C, Saußele S. Chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2021;398:1914-1926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sawyers CL, Hochhaus A, Feldman E, Goldman JM, Miller CB, Ottmann OG, Schiffer CA, Talpaz M, Guilhot F, Deininger MW, Fischer T, O'Brien SG, Stone RM, Gambacorti-Passerini CB, Russell NH, Reiffers JJ, Shea TC, Chapuis B, Coutre S, Tura S, Morra E, Larson RA, Saven A, Peschel C, Gratwohl A, Mandelli F, Ben-Am M, Gathmann I, Capdeville R, Paquette RL, Druker BJ. Imatinib induces hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in myeloid blast crisis: results of a phase II study. Blood. 2002;99:3530-3539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 882] [Cited by in RCA: 812] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Aleem A, Siddiqui N. Chronic myeloid leukemia presenting with extramedullary disease as massive ascites responding to imatinib mesylate. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1097-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Specchia G, Palumbo G, Pastore D, Mininni D, Mestice A, Liso V. Extramedullary blast crisis in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 1996;20:905-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nuwal P, Dixit R, Dargar P, George J. Pleural effusion as the initial manifestation of chronic myeloid leukemia: Report of a case with clinical and cytologic correlation. J Cytol. 2012;29:152-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Deshpande AS, Bitey SA, Raut A. Case Report Ascites in CML - A Rare Extramedullary Manifestation. Vidarbha Journal of Internal Medicine. 2015;18:64-66. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Ridha N, Budiman KY, Oehadian A. Pleural Effusion in Blast Crisis Phase of Chronic Myeloid. Clinics in Oncology. 2020;5:5-7. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Kim HW, Lee SS, Ryu MH, Lee JL, Chang HM, Kim TW, Chi HS, Kim WK, Lee JS, Kang YK. A case of leukemic pleural infiltration in atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:936-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4245] [Cited by in RCA: 5303] [Article Influence: 589.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hehlmann R. How I treat CML blast crisis. Blood. 2012;120:737-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |