Published online Apr 15, 2017. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v8.i4.165

Peer-review started: October 6, 2016

First decision: January 16, 2017

Revised: January 24, 2017

Accepted: February 18, 2017

Article in press: February 20, 2017

Published online: April 15, 2017

Processing time: 129 Days and 2.5 Hours

To review impacts of interventions involving self-management education, health coaching, and motivational interviewing for type 2 diabetes.

A thorough review of the scientific literature on diabetes care and management was executed by a research team.

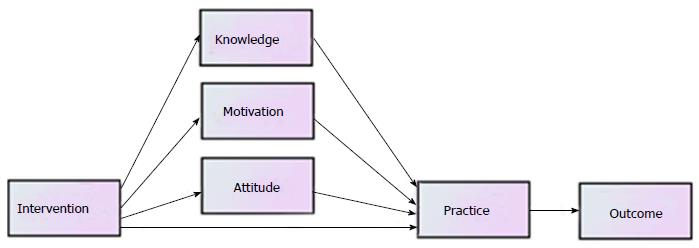

This article summarizes important findings in regard to the validity of developing a comprehensive behavioral system as a framework for empirical investigation. The behavioral system framework consists of patients’ knowledge (K), motivation (M), attitude (A), and practice (P) as predictor variables for diabetes care outcomes (O). Care management strategies or health education programs serve as the intervention variable that directly influences K, M, A, and P and then indirectly affects the variability in patient care outcomes of patients with type 2 diabetes.

This review contributes to the understanding of the KMAP-O framework and how it can guide the care management of patients with type 2 diabetes. It will allow the tailoring of interventions to be more effective through knowledge enhancement, increased motivation, attitudinal changes, and improved preventive practice to reduce the progression of type 2 diabetes and comorbidities. Furthermore, the use of health information technology for enhancing changes in KMAP and communications is advocated in health promotion and development.

Core tip: A complex set of behavioral and cognitive variables related to diabetes care may influence adherence and self-care practice of patients with type 2 diabetes. This systematic review is guided by a behavioral system framework. Care management strategies or health education programs serve as intervention variables that may directly influence a patient’s knowledge, motivation and attitude, self-care practice, and outcomes. This review summarizes key findings in regard to the validity of developing a comprehensive behavioral system as a framework for future empirical investigation.

- Citation: Wan TTH, Terry A, McKee B, Kattan W. KMAP-O framework for care management research of patients with type 2 diabetes. World J Diabetes 2017; 8(4): 165-171

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v8/i4/165.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v8.i4.165

More than 29 million people in the United States have diabetes[1]. Type 2 diabetes, which accounts for 90% to 95% of all cases, occurs when the body develops insulin resistance and cells no longer transport glucose using insulin. This leads to an overproduction from the pancreas, and eventually the pancreas does not produce enough insulin when blood sugar levels increase[2]. In 2012, the total estimated cost of diagnosed diabetes in the United States was $245 billion, including $176 billion in direct medical costs and $69 billion in lost productivity[3]. Diabetes is associated with higher risk of blindness, kidney failure, heart disease, stroke, and amputations[1]. Diabetes control requires a systematic effort of adherence to medical regimens and preventive practice in diet and exercise. A comprehensive framework for promoting diabetes care is proposed in this review of the empirical literature.

This review is centered on type 2 diabetes from a behavioral system perspective and guided by the scientific literature published in social, behavioral, and medical science journals. The research team collectively conducted the review of studies published in the scientific literature. Both conceptual and empirical developments in health education and research are highlighted in the review.

Behavioral and social scientists have considered a behavioral systems approach to medical adherence studies. Their research is centered in the identification of how knowledge, attitude, and preventive practice may influence the variability in health and behavioral outcomes. However, this approach fails to articulate causal-specific links among these major contributing factors to outcome variations. Furthermore, the lack of attention to motivational factors in search for the determinants of health care outcomes has compounded the investigative problem that has hindered the full explication of the important role of motivation in the KAP studies.

The KMAP-O framework can be used to guide care management of type 2 diabetes patients. The first construct of the KMAP-O model is knowledge. Knowledge is “the acquisition, retention, and use of information or skills”[4,5]. Type 2 diabetes patients should have the knowledge to understand the condition, its progression, and necessary self-care practices[5].

The second construct in the model is motivation. Motivation is an individual’s desire or willingness to behave in a certain way. A person can be described as unmotivated if he or she feels no impetus or inspiration to act, while a person who is energized or activated toward an end is characterized as motivated[6].

Following knowledge and motivation, attitude is the next construct in the KMAP-O framework. Attitude is a “psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor”[7]. A patient’s attitude toward diabetes involves any preconceived ideas about the condition and its management, any feelings and emotions toward aspects of diabetes and diabetes care, and the aptness to behave in particular ways about diabetes and its management[5].

Practice is the fourth construct in the model. Practice is a demonstration of “the acquisition of knowledge (increased understanding of a problem/condition) and any change in attitude caused by the removal of misconceptions about the condition”[5]. The following seven key behaviors to practice in diabetes management, as identified by the American Association of Diabetes Educators, are healthy eating, physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, medication taking, problem solving related to diabetes self-care, reducing risks of acute and chronic complication, and healthy coping[8].

The last construct in the framework is outcome. Outcomes that are commonly assessed in type 2 diabetes patients are psychosocial measures such as quality of life (QoL), and physical measures such as blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), body weight, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, and lipid levels. The causal specifications among the KMAP-O components are portrayed in Figure 1. This model suggests that health education or behavioral intervention(s) may directly affect knowledge, motivation, attitude and practice. The changes in knowledge, motivation and attitude may also directly influence practice variations in diabetes control. Consequently, better practice behavior in diabetes care management may result in a positive improvement in clinical and self-reported healthcare outcomes. These causal specifications enable researchers to generate multiple, testable hypotheses in empirical studies on care management effectiveness for type 2 diabetes.

The management of type 2 diabetes requires modification of complex behavior and practices to achieve optimal outcomes. Interventions that encourage these changes include self-management education, health coaching, and motivational interviewing. Self-management education is “a collaborative and ongoing process intended to facilitate the development of knowledge, skills, and abilities that are required for successful self-management of diabetes”[9,10]. Health coaching aims to help individuals achieve goals through the assistance of coaches that have received specific training to facilitate the change process, elicit motivation, and build trust, self-efficacy, and growth-promoting relationships. It is appropriate for type 2 diabetes management given that the coaching model is intended to address psychosocial factors and lifestyle behaviors[11]. Health coaching interventions “target health behavior changes aligned with self-determined goals leading to improved physical and mental health outcomes”[12,13]. Motivational interviewing is a patient-centered communication technique that involves open-ended questions, reflective listening, and support for patient autonomy and self-efficacy with aims to evoke intrinsic motivation of an individual to make behavior changes[14]. The objective of this review is to summarize interventions that have significantly improved knowledge, motivation, attitude, practice, and outcomes of type 2 diabetes patients.

Education on knowledge, attitude, and practice: A study has reported that a health education intervention had a positive impact on the knowledge, attitude, and practice of individuals with type 2 diabetes[15].

A health education intervention consisting of 18 sessions for South Asian diabetes patients in Scotland significantly improved the low baseline scores for knowledge (+ 12.5%), serious attitudes toward diabetes (+ 13.5%), and practice (+ 20.0%)[15].

Education on knowledge, attitude, practice, and outcomes: Studies have reported that health education interventions had a positive impact on the knowledge, attitude, practice, and outcomes of individuals with type 2 diabetes[16-18].

A pharmacist-provided patient counseling in India on patients’ perceptions about disease management and QoL improved knowledge, attitude, and practices scores; reduced mean capillary blood glucose levels; and improved mean scores for QoL[16].

A counseling intervention for patients during monthly sessions lasting 20-25 min for three months in South India significantly improved KAP scores, especially knowledge and attitude, and improved the outcome for postprandial blood glucose levels. However, no significant improvements in practice were reported due to high baseline scores[17].

A meta-analysis found that self-management education continually improves the outcome of HbA1c levels and suggested that knowledge and attitude continue to influence practice and outcome after the educational interventions are over[18].

Education on knowledge and outcomes: Studies have reported that health education interventions had a positive impact on the knowledge and outcomes of individuals with type 2 diabetes[19,20].

A systematic review of 72 studies evaluating the effectiveness of self-management education lasting for a period of six months or less concluded that such interventions significantly improve knowledge and glycemic control while having variable effects on lipids[19].

A community, pharmacy-based diabetes education intervention based on the American Diabetes Association standards in the United States improved knowledge of diabetes, HbA1c levels, fasting blood glucose levels, lipid levels, and blood pressure measurements[20].

Education on attitude: A study has demonstrated that a health education intervention had a positive impact on the attitude of individuals with type 2 diabetes[21].

Diabetes group education for urban, newly diagnosed patients in Ireland continually improved the patients’ attitudes about the seriousness of the condition over time[21].

Education on practice and outcomes: A study has reported that a health education intervention had a positive impact on the practice and outcomes of individuals with type 2 diabetes[22].

During a health education intervention that involved access to interactive, self-paced web-based tutorials supplemented with a printout, changes in the practices of healthy eating, physical activity, blood sugar monitoring, blood pressure monitoring, foot care, and avoidance of smoking were associated with significant improvements in the outcome of HbA1c levels[22].

Education on outcomes: Studies have reported that health education interventions had a positive impact on the outcomes of individuals with type 2 diabetes[9].

A systematic review of 118 unique interventions, which involved various elements to improve participants’ knowledge, skills, and ability to perform self-management activities as well as informed decision-making around goal setting, found data demonstrating that engagement in diabetes self-management education significantly decreases HbA1c levels[9].

Coaching on attitude and outcomes: A study has reported that health coaching interventions had a positive impact on the attitude and outcomes of individuals with type 2 diabetes[11].

An integrative health coaching intervention in the United States consisting of fourteen 30-min sessions conducted over the phone, which focused on individualized visions of health and self-chosen goals, significantly decreased perceived barriers to medication adherence and improved patient activation, perceived social support, benefit finding, and HbA1c levels[11].

Coaching on practice: A study has reported that health coaching interventions had a positive impact on the practice of individuals with type 2 diabetes[23].

A three-month peer-led self-management coaching program that involved three monthly home visits and follow-up contacts through phone and email for recently diagnosed patients in the Netherlands improved the self-efficacy in intervention group patients with low baseline self-efficacy[23].

Coaching on practice and outcomes: Studies have reported that health coaching interventions had a positive impact on the practice and outcomes of individuals with type 2 diabetes[24,25].

A six-month coaching intervention in Australia consisting of monthly phone-based coaching sessions to establish and assess progress toward individualized goals for self-care activities (e.g., diet, activity) and monitoring (e.g., foot and eye care, vaccinations) in addition to usual care significantly improved the practices of physical activity and adherence to monitoring exams for complications, as well as the outcomes of HbA1c levels, fasting glucose, and diastolic blood pressure[24].

A 16-mo health coaching intervention at outpatient clinics in Turkey which included five or six in-person meetings and three or four telephone coaching sessions significantly improved the practice of oral health and outcome of HbA1c levels, particularly among high-risk patients, compared to formal health education[25].

Coaching on outcomes: Studies have reported that health coaching interventions had a positive impact on the outcomes of individuals with type 2 diabetes[12,26,27].

A health coaching intervention in Canada which involved weekly communication with a health coach either in-person, using a mobile device, or using a web-based wellness platform to promote goal setting and monitor progress, as well as access to a free community exercise center, improved the outcomes of HbA1c levels at three months and of body weight and waist circumference at three and six months[12].

A healthcare provider-mediated, remote coaching system via a PDA-type glucometer and the Internet in South Korea significantly reduced HbA1c levels (8.0% vs 7.5%) and total cholesterol (10.7 mmol/L vs 10.4 mmol/L) at three-month follow-up[26].

A clinic-based peer health coaching intervention for low-income patients with poorly controlled diabetes in the United States significantly decreased HbA1c levels to under 7.5% for 22.0% of coached mmol/L 14.9% of usual care patients at five months[27].

Motivation on knowledge and attitude: A study has reported that motivation had a positive impact on the knowledge and attitude of individuals with type 2 diabetes[28].

Training for general practitioners in motivational interviewing in Denmark significantly impacted the patients in the intervention group, who became more autonomous and motivated in their inclination to change behavior, more conscious of the importance of controlling their diabetes, and had a significantly better understanding of the ability to prevent complications[28].

Motivation on practice: Studies have reported that motivation had a positive impact on the practice of individuals with type 2 diabetes[29-31].

A 12-mo motivational interviewing-based personalized program in the United Kingdom significantly improved healthy eating habits[29].

Motivational interviewing counseling sessions for newly diagnosed patients in the Netherlands significantly improved the practice of healthy eating by reducing saturated fats[30].

A three-month motivational interviewing-based information-motivation-behavioral skills intervention for type 2 diabetes patients in the United States significantly improved the practice of healthy eating[31].

Motivation on practice and outcomes: Studies have reported that motivation had a positive impact on the practice and outcomes of individuals with type 2 diabetes[32-37].

A 16-wk motivational interviewing intervention, in addition to a behavioral weight control program, for obese female patients in the United States significantly improved treatment adherence through higher attendance at group meetings, increased diary entries, better blood glucose monitoring, and the outcome of HbA1c levels[32].

A motivational interviewing intervention, in addition to an 18-mo weight management program, for overweight and uncontrolled female patients in the United States significantly improved treatment adherence through higher attendance at group meetings and increased diary entries, as well as the outcomes of weight loss and HbA1c levels[33].

A three-month motivational interviewing intervention in Taiwan that involved a 45- to 60-min interview, in addition to hospital-based educational sessions and the hospital’s support group for diabetes patients, significantly improved patients’ self-management, self-efficacy, QoL, and HbA1c levels[34].

A 13-wk motivational interviewing-based eating behavior modification program for obese patients in Thailand significantly improved the practice of healthy eating, HbA1c levels, and BMI[35].

A six-month motivational interviewing intervention with 30-min monthly sessions focusing on behavior change in an outpatient clinic after discharge for hospitalized patients with poor long-term glycemic control in China significantly improved the practice of self-management and the outcome of homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance scores[36].

A motivational interviewing intervention for African American adults in the United States significantly increased the odds of participants adhering to recommended physical activity level (66.7% vs 38.8%) and significantly decreased glucose levels and BMI[37].

Motivation on outcomes: Studies have reported that motivation had a positive impact on the outcomes of individuals with type 2 diabetes[38,39].

A motivational interviewing intervention and a cognitive behavioral group training intervention each consisting of four 90-min sessions in Iran significantly lowered the mean BMI[38].

A two-year motivational interviewing-based behavior change counseling program for high-risk patients in the United States significantly improved blood pressure[39].

The empirical literature illustrates the beneficial impacts of interventions involving self-management education, health coaching, and motivational interviewing for diverse type 2 diabetes patients. This review contributes to the understanding of the KMAP-O framework and how it can guide the care management of patients with type 2 diabetes. It will allow the tailoring of interventions to be more effective through knowledge enhancement, increased motivation, attitudinal changes, and improved preventive practice to reduce the progression of type 2 diabetes and comorbidities. To ensure the effectiveness of such interventions, outcome tracking can be conducted through longitudinal observations of patients and their knowledge, motivation levels, attitude, practice, and outcomes.

Multiple clinical symptoms such as low plasma adiponectin[40], obesity and sarcopenia[41], and defective fat oxidation capacity[42] are linked with type 2 diabetes. Thus, clinical interventions should be designed carefully through causal specifications of the etiology of type 2 diabetes. Obesity is considered a leading cause for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. It is concluded that diabetes care should not only pay attention to clinical symptoms or etiologies associated with diabetes, but also consider behavioral factors that could either impede or facilitate patient adherence and self-care management of a controllable chronic condition. Furthermore, the efficacy of health promotional strategies, using the KMAP-O framework, can be demonstrated by carefully designed and executed clinical trial studies that are augmented with health information technology[43].

This manuscript summarized the relevance of behavioral components of health education that can improve diabetes care. Type 2 diabetes is considered an ambulatory care sensitive condition. Proper implementation of care management strategies can prevent unnecessary hospital admissions and readmissions.

This manuscript introduced a comprehensive model grounded by behavioral and social science theories through a careful review of the scientific literature and document relevant strategies for implementing diabetes education and achieving diabetes control.

This manuscript articulated the potential causal mechanisms for enhancing preventive practice and improving patient care outcomes of type 2 diabetes.

This manuscript suggested plausible causal links between health educational intervention and patient care outcomes mediated by behavioral factors such as knowledge, motivation, attitude, and practice relevant to diabetes care.

This manuscript is a literature review on impacts of interventions involving self-management education, health coaching, and motivational interviewing for diverse type 2 diabetes patients.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hssan MMA, Sanal MG S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Working to reverse the US epidemic ([accessed 2016 Aug 8]). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/diabetes.htm. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Types of diabetes. National Institutes of Health (Published February 2014. [accessed. 2016;Aug 11]) Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/types. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | American Diabetes Association. The cost of diabetes (Last Reviewed October 21, 2013. Last Edited June 22, 2015. [accessed. 2016;Aug 11]) Available from: http://www.diabetes.org/advocacy/news-events/cost-of-diabetes.html. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Badran IG. Knowledge, attitude and practice the three pillars of excellence and wisdom: A place in the medical profession. East Mediterr Health J. 1995;1:8-16. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Wan TTH, Rav-Marathe K, Marathe S. A systematic review on the KAP-O framework for diabetes education and research. Med Res Arch. 2016;3. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25:54-67. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7242] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2797] [Article Influence: 116.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Eagly AH, Chaiken S. The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Soc Cogn. 2007;25:582-602. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 453] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, Haas LB, Hosey GM, Jensen B, Maryniuk M, Peyrot M, Piette JD, Reader D. National Standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 Suppl 1:S89-S96. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 112] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:926-943. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 474] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 512] [Article Influence: 64.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Haas L, Maryniuk M, Beck J, Cox CE, Duker P, Edwards L, Fisher EB, Hanson L, Kent D, Kolb L. National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2393-2401. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wolever RQ, Dreusicke M, Fikkan J, Hawkins TV, Yeung S, Wakefield J, Duda L, Flowers P, Cook C, Skinner E. Integrative health coaching for patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:629-639. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 200] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Wayne N, Perez DF, Kaplan DM, Ritvo P. Health Coaching Reduces HbA1c in Type 2 Diabetic Patients From a Lower-Socioeconomic Status Community: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 137] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Huffman M. Health coaching: a new and exciting technique to enhance patient self-management and improve outcomes. Home Healthc Nurse. 2007;25:271-274; quiz 275-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ekong G, Kavookjian J. Motivational interviewing and outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:944-952. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 110] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Baradaran HR, Knill-Jones RP, Wallia S, Rodgers A. A controlled trial of the effectiveness of a diabetes education programme in a multi-ethnic community in Glasgow [ISRCTN28317455]. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:134. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Adepu R, Rasheed A, Nagavi BG. Effect of patient counseling on quality of life in type-2 diabetes mellitus patients in two selected South Indian community pharmacies: A study. Indian J Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2007;69:519-524. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Malathy R, Narmadha M, Ramesh S, Alvin JM, Dinesh BN. Effect of a diabetes counseling programme on knowledge, attitude and practice among diabetic patients in Erode district of South India. J Young Pharm. 2011;3:65-72. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1159-1171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1160] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1119] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:561-587. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1299] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1197] [Article Influence: 52.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hogue VW, Babamoto KS, Jackson TB, Cohen LB, Laitinen DL. Pooled results of community pharmacy-based diabetes education programs in underserved communities. Diabetes Spectr. 2003;16:129-133. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Clarke A. Effects of routine education on people newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. European Diabetes Nursing. 2009;6:88-94. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rav-Marathe K, Wan TTH, Marathe S. The effect of health education on clinical and self-reported outcomes of diabetes in a medical practice. J Integr Des Process Sci. 2016;20:45-63. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | van der Wulp I, de Leeuw JR, Gorter KJ, Rutten GE. Effectiveness of peer-led self-management coaching for patients recently diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2012;29:e390-e397. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Varney JE, Weiland TJ, Inder WJ, Jelinek GA. Effect of hospital-based telephone coaching on glycaemic control and adherence to management guidelines in type 2 diabetes, a randomised controlled trial. Intern Med J. 2014;44:890-897. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cinar AB, Schou L. The role of self-efficacy in health coaching and health education for patients with type 2 diabetes. Int Dent J. 2014;64:155-163. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cho JH, Kwon HS, Kim HS, Oh JA, Yoon KH. Effects on diabetes management of a health-care provider mediated, remote coaching system via a PDA-type glucometer and the Internet. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:365-370. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Thom DH, Ghorob A, Hessler D, De Vore D, Chen E, Bodenheimer TA. Impact of peer health coaching on glycemic control in low-income patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2007;11:137-144. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 214] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Borch-Johnsen K, Christensen B. General practitioners trained in motivational interviewing can positively affect the attitude to behaviour change in people with type 2 diabetes. One year follow-up of an RCT, ADDITION Denmark. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27:172-179. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Clark M, Hampson SE, Avery L, Simpson R. Effects of a tailored lifestyle self-management intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes. Br J Health Psychol. 2004;9:365-379. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Brug J, Spikmans F, Aartsen C, Breedveld B, Bes R, Fereira I. Training dietitians in basic motivational interviewing skills results in changes in their counseling style and in lower saturated fat intakes in their patients. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39:8-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Osborn CY, Amico KR, Cruz N, O’Connell AA, Perez-Escamilla R, Kalichman SC, Wolf SA, Fisher JD. A brief culturally tailored intervention for Puerto Ricans with type 2 diabetes. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37:849-862. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Smith DE, Heckemeyer CM, Kratt PP, Mason DA. Motivational interviewing to improve adherence to a behavioral weight-control program for older obese women with NIDDM. A pilot study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:52-54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 249] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | West DS, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1081-1087. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 240] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chen SM, Creedy D, Lin HS, Wollin J. Effects of motivational interviewing intervention on self-management, psychological and glycemic outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:637-644. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wattanakorn K, Deenan A, Puapan S, Kraenzle Schneider J. Effects of an eating behaviour modification program on thai people with diabetes and obesity: A randomised clinical trial. Pacific Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2013;17:356-370. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Li M, Li T, Shi BY, Gao CX. Impact of motivational interviewing on the quality of life and its related factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with poor long-term glycemic control. IJNSS. 2014;1:250-254. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chlebowy DO, El-Mallakh P, Myers J, Kubiak N, Cloud R, Wall MP. Motivational interviewing to improve diabetes outcomes in African Americans adults with diabetes. West J Nurs Res. 2015;37:566-580. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Pourisharif H, Babapour J, Zamani R, Besharat MA, Mehryar AH, Rajab A. The effectiveness of motivational interviewing in improving health outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5:1580-1584. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Gabbay RA, Añel-Tiangco RM, Dellasega C, Mauger DT, Adelman A, Van Horn DH. Diabetes nurse case management and motivational interviewing for change (DYNAMIC): results of a 2-year randomized controlled pragmatic trial. J Diabetes. 2013;5:349-357. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, Tataranni PA. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1930-1935. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1862] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1927] [Article Influence: 83.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Han TS, Wu FC, Lean ME. Obesity and weight management in the elderly: a focus on men. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27:509-525. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Golay A, Ybarra J. Link between obesity and type 2 diabetes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19:649-663. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 167] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Rav-Marathe K, Wan TTH, Marathe S. The effect of health education on clinical and self-reported outcomes of diabetes in a medical practice. J Integrated Design Process Sci. 2016;20:45-64. [Cited in This Article: ] |