Published online Jan 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i1.110

Peer-review started: September 14, 2023

First decision: October 8, 2023

Revised: November 10, 2023

Accepted: November 15, 2023

Article in press: November 15, 2023

Published online: January 15, 2024

The incidence of gastric cancer remains high, and it is the sixth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. Oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography is a simple, non-invasive, and painless method for the diagnosis of gastric tumors.

To explore the diagnostic value of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the detection of gastric tumors.

The screening results based on oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and electronic gastroscopy were compared with those of the postoperative patholo

Among 42 patients with gastric tumors enrolled in the study, the diagnostic accordance rate was 95.2% for oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (n = 40) and 90.5% for electronic gastroscopy (n = 38) compared with postoperative pathological examination. The Kappa value of consistency test with pathological findings was 0.812 for oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and 0.718 for electronic gastroscopy, and there was no significant difference between them (P = 0.397). For the TNM staging of gastric tumors, the accuracy rate of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography was 81.9% for the overall T staging and 50%, 77.8%, 100%, and 100% for T1, T2, T3, and T4 staging, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity were both 100% for stages T3 and T4. The diagnostic accuracy rate of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography was 93.8%, 80%, 100%, and 100% for stages N0, N1-N3, M0, and M1, respectively.

The accordance rate of qualitative diagnosis by oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography is comparable to that of gastroscopy, and it could be used as the preferred method for the early screening of gastric tumors.

Core Tip: In this study, a total of 42 gastric tumor patients underwent both oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and gastroscopy. The diagnostic findings and the postoperative pathological examination results were compared to evaluate the diagnostic value of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the diagnosis of gastric tumors.

- Citation: Wang CY, Fan XJ, Wang FL, Ge YY, Cai Z, Wang W, Zhou XP, Du J, Dai DW. Clinical value of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in diagnosis of gastric tumors. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(1): 110-117

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i1/110.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i1.110

Gastric tumors, especially gastric cancer, is one of the most common gastrointestinal tumors worldwide[1]. The incidence of gastric cancer remains high, and it is the sixth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide[2], posing a great disease burden. Despite the high incidence of gastric cancer, the diagnosis of gastric tumors mainly depends on gastroscopy, and there are no suitable methods for large-scale screening[3]. As gastroscopy is invasive and may cause discomfort, it is refused by some patients[4]. Moreover, the efficacy of gastroscopy is relatively unsatisfactory, and it cannot meet the requirements of early screening of gastric cancer[5]. With the advancements of high-resolution color Doppler sonography and techniques of ultrasonography, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography has addressed the challenges associated with gastroscopy[6-9]. Between March 2020 and July 2022, a total of 42 gastric tumor patients undergoing oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and gastroscopy at Beijing Hospital were enrolled in this study. The diagnostic findings and postoperative pathological examination results were compared to evaluate the diagnostic value of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for gastric tumors.

In this study, data of 42 patients (25 males and 17 females) diagnosed with gastric tumors during clinic visits or hospitalization at Beijing Hospital between March 2020 and July 2022 were retrospectively analyzed. The mean age of these patients was 53.1 ± 17.2 years (range, 38 to 75 years). All the patients were admitted to the hospital for symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, weight loss, and abdominal dull pain. Patients incapable of food intake and those with gastrointestinal tract obstruction were excluded. The diagnosis in all the patients was performed using electronic gastroscopy and postoperative pathological findings were reported.

Diagnostic medical devices: Siemens Sequoia color Doppler ultrasound system was used in this study with frequencies of probe ranging from 3.5 to 5.0 MHz. The gastrointestinal contrast agent “Tianxia” was used, which has a sound velocity of 1545 m/s and pH of 6.24. Ultrasound can clearly reveal the structure of the stomach due to the difference in echo

Examination method: The patients were asked to avoid greasy food for 2 d before the examination and barium enema for 3 d before the examination, and have semi-liquid low-residue diet or light liquid diet the day before the examination. Thereafter, the patients were fasting after dinner the day before the examination to the morning of the day of the examination, and did not drink water for 12 h. The contrast agent was prepared in suspension according to the manufacturer’s instructions, thoroughly mixed and orally administered at a dose of 500 to 600 mL. The patients were placed in the supine position, and the solid organs in the abdominal cavity (including the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen, and bilateral kidneys) were routinely scanned. Then the patients were placed in the sitting position, the contrast agent was orally taken again, and ultrasound scanning was simultaneously performed. The patients were mainly placed in the sitting, supine, and right lateral positions, and the ultrasound probe was used for continuous scanning at the body surface along the gastric anatomical positions at the vertical and transverse sections. The gastric fundus was scanned in the left lateral position, while the gastric cardia, fundus, body, and antrum were scanned in the right lateral position. After a mass was detected, the position, size, morphology, mobility, and thickness of the gastric wall were carefully evaluated. The relationship of the mass with surrounding tissues, as well as other abnormalities such as the presence of obstruction, was observed, and color Doppler ultrasound was used to explore the blood flow in the mass. The lymphocyte expansion in the abdominal cavity and retroperitoneal area, metastases in organs, and presence of seroperitoneum were also observed, and computer image workstation was used to record the images.

Criteria for evaluation: After the gastric cavity is filled, the normal gastric wall shows five layers of structures of “high-low-high-low-high” echoes, respectively, which represents the echo of interface between the mucosal surface and gastric cavity, muscularis mucosa, submucosal layer, muscularis propria, serosal layer, and organs outside the mucosal layer. Gastric wall thickness is an important parameter for ultrasound diagnosis of gastric cancer[11]. In patients with gastric cancer, the manifestations mainly include thickening of low echo of the gastric wall, ulceration, mass formation, disturbance of the five layers, and interruption of the continuity[12]. In contrast, gastric ulcers usually show localized hypoechoic wall thickening, uneven or depressed mucosal surface, and hyperechoic lines on the mucosal surface, along with air retention at the bottom[13].

TNM represents the depth of tumor invasion to gastric wall, lymph node metastases, and distal metastases (UICC, 5th edition). Specifically, T1 indicates the tumor invading the mucus or submucosal layer; T2 indicates the tumor invading the muscular layer or subserosal layer; T3 indicates the tumor invading through the serosal layer but not invading the adjacent organs; and T4 indicates the tumor invading through the serosal layer into the adjacent organs. N0 indicates no lymph node metastasis; N1 indicates that the number of lymph nodes with metastases is 1 to 6; N2 indicates that the number of lymph nodes with metastases is 7 to 15; and N3 indicates that the number of lymph nodes with metastases is > 16. M0 indicates no distal metastasis, and M1 indicates the presence of distal metastases[14].

Evaluation method: Postoperative pathological findings were used as the gold standard for diagnosing gastric tumors. The accuracy of qualitative and quantitative evaluation of gastric tumors by oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and gastroscopy were compared. The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the TNM staging of gastric tumors were investigated, using postoperative pathological findings as the reference standard.

SPSS 25 software was used for statistical analyses. Measurement data, described as the mean and standard deviation, were compared by the paired t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The sensitivity of diagnosis refers to the percentage of patients with positive results of examination, and specificity of diagnosis refers to the percentage of patients with negative results of examination. Sign test was used for the statistical analysis of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of the diagnostic indicators. PPV is calcuclated as the number of true positive cases of certain indicator/total number of positive cases of the indicator. NPV is calcuclated as the number of true negative cases of certain indicator/total number of negative cases of the indicator.

In this study, the size of lesions detected by oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography was 1.0 to 7.2 cm. The increase of gastric wall thickness was 0.7 to 2.6 cm. The normal gastric wall structures disappeared. Most of the plica mucosa disappeared or became rigid, and the gastric cavity decreased. The lesions invaded the surrounding tissues along the layers of the gastric wall and the full-thickness of the gastric wall in some cases. The blood flow signal was relatively high in large gastric tumors, and the circuitous blood vessels could be easily displayed. The blood flow signals in stromal tumors were low and disperse.

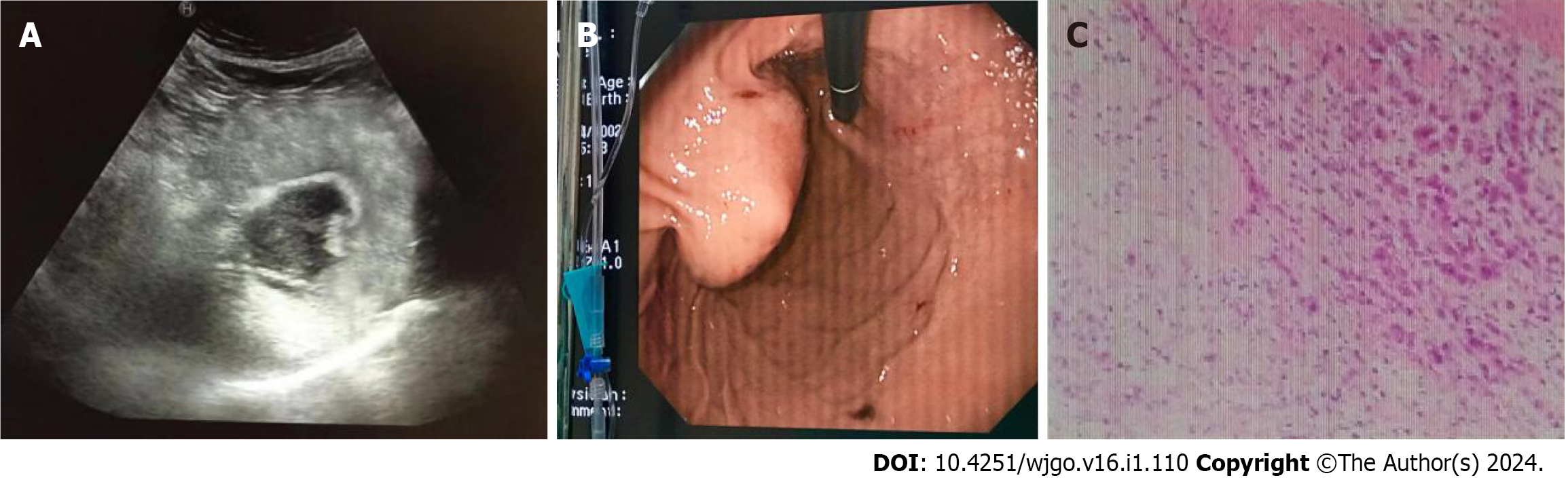

Gastric cancer was diagnosed in 40 patients (Figure 1), stromal tumors in two (Figure 2), and leiomyosarcoma in two using oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Compared with the postoperative pathological findings, the diagnosis accordance rate of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for gastric cancer was 95.2% (40/42), and Kappa value was 0.812 (P < 0.05). The accordance rate of electronic gastroscopy was 90.5% (38/42), and Kappa value was 0.718 (P < 0.05). The lesions in four patients were below the mucosa on gastroscopy and could not be displayed.

Compared with the postoperative pathological diagnostic results, the accordance rate of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for TNM staging (accuracy rate) was 95.0% (38/40), 95.0% (38/40), 100.0% (40/40), and 100.0% (40/40) for T1, T2, T3, and T4 tumors, respectively. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 100.0% (2/2), 94.7% (36/38), 50.0% (2/4), and 100.0% (36/36) for T1 stage, 77.8% (7/9), 100.0% (31/31), 100.0% (7/7), and 93.9% (31/33) for T2 stage, 100.0% (20/20), 100.0% (20/20), 100.0% (20/20), and 100.0% (20/20) for T3 stage, and 100.0% (9/9), 100.0% (31/31), 100.0% (9/9), and 100.0% (31/31) for T4 stage, respectively (Table 1). The accordance rate of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for NM staging was 95.0% (38/40) for N0 stage, 95.0% (38/40) for N1-N3 stages, 100.0% (40/40) for M0 stage, and 100.0% (40/40) for M1 stage (Table 2). Totally, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography detected 8 Lymph nodes with metastases (N1) in two patients, 41 Lymph nodes with metastases (N2) in four patients, and 37 Lymph nodes with metastases (N3) in two patients, most of which were at the gastric fundus or around the liver and great abdominal vessels. In addition, distal metastases (M1) were detected in the liver in four patients.

| Pathological staging | n | Ultrasound staging | ||

| T1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| T2 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 0 |

| T3 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| T4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pathological staging | n | Ultrasound staging | |||

| ON | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N1-N3 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| MO | 36 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 |

| M1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

In recent years, the incidence and death rates of stomach cancer have remained high[2]. The detection of gastric diseases is a major challenge for doctors. In China, more than 80% of gastric cancer patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage because they have no specific symptoms. Thus, the 5-year survival rate of gastric cancer is low[15]. Screening for gastric cancer allows for early diagnosis and treatment, which will improve patient survival rates[16]. Conventional gastroscopy is considered as the preferred method for diagnosing gastric tumors, which directly displays the lesions and can also perform biopsy under direct vision for pathological examinations[3]. The sensitivity and specificity of gastroscopy are relatively high. However, gastroscopy involves major trauma and requires general anesthesia to achieve painlessness, which will cause certain risks[5]. Therefore, many patients are unwilling to undergo gastroscopy, even though the disease has already progressed to middle or advanced stage at diagnosis, and thus they missed the best timing for the treatment of gastric tumors. Gastric cancer usually occurs in people over 50 years of age. However, gastroscopy is still poorly tolerated and adhered by the elderly due to objective and psychological factors such as age and physical condition[17]. With the advancements in high-resolution color Doppler sonography and techniques of ultrasonography, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography provides a new alternative for the detection of gastric tumors, which is easy to operate, safe, non-invasive, minimally invasive, and capable of displaying the size, morphology, internal structures, relationships with surrounding organs, and blood flow of gastric tumors from multiple aspects, angles, and layers. Previous studies have shown its value in gastric diseases[18-20]. Especially, it can help asymptomatic patients to detect gastric cancer and improve the early diagnosis and treatment[21]. For the tumor positioning in this study, the accordance rate was 95.2% (n = 40) for oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and 90.5% (n = 38) for electronic gastroscopy. However, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography cannot allow biopsy of lesion tissues, and is influenced by gastric emptying and contrast agent. Therefore, the differentiation between benign and malignant gastric tumors < 1 cm is relatively difficult in ultrasound examination. Although the diagnostic value of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for gastric tumors has been established[22], the most commonly used method in clinical practice is electronic gastroscopy, indicating clinicians’ insufficient understanding of the advantages of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the diagnosis of gastric tumors. Previous studies also have shown that oral ultrasonography is more accurate than conventional ultrasonography in detecting the site, size, number, and extent of gastric lesions, and is almost comparable to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in detecting small gastric lesions[23].

The normal gastric wall shows five layers of structures of “high-low-high-low-high” echoes on ultrasonogram, and the thickness of the gastric wall > 5 mm is considered abnormal. A gastric tumor originates from the mucosal layer and gradually spreads to the submucosal layer, muscular layer, and serosal layer, and finally leads to abnormal thickening of the gastric wall or grows toward the intra- or extra-gastric cavity, which provides a good basis for the T staging of tumors by sonography[12].

For the evaluation of gastric wall invasion depth, the accuracy rate of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography was 95.0%, 95.0%, 100.0%, and 100.0% for stage T1, T2, T3, and T4 gastric tumors, respectively. The accuracy rate for stages T1 and T2 tumors was the lowest, which could be associated with the non-specific lesion characteristics, and the unclear boundary between the mucosal layer and muscular layer induced by uneven gastric wall thickening. Ultrasound contrast agent could provide good acoustic window but could not eliminate the near field artifacts. The greater curvature in coronal oblique view is in the near field, and thus the evaluation of gastric wall invasion depth is difficult. However, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography has high accuracy for diagnosing stages T3 and T4 gastric tumors, and could be used as a reference by doctors for identifying suitable operation methods.

Due to the insidious onset of gastric tumors, their symptoms are atypical. Some of the patients have peripheral lymph node metastases, celiac and pelvic lymph node metastases, and liver metastases at diagnosis. The detection of metastatic lesions could influence the selection of treatment strategy and outcomes of operation. Oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography has specific manifestations for the diagnosis of gastric tumors, which could detect the damages of gastric wall structures early, evaluate the degree of invasion, and detect liver, celiac, and pelvic lymph node metastases more easily, and it has high diagnostic accordance rate with the qualitative diagnosis by postoperative pathological examinations[24]. In this study, the accuracy of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography was 95.0% for preoperative diagnosis of stage N0 gastric tumor, 95.0% for stages N1-N3 gastric tumor, and 100% for stages M0 and M1 gastric tumors. Gastroscopy could not evaluate the submucosal lesions, exophytic tumors, and metastases in organs in the abdominal cavity, while oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography has unique advantages, which could effectively overcome the limitations of gastroscopy[25]. Of the 42 patients with gastric tumors in this study, two had stromal tumors and two had gastric leiomyosarcoma that could not be visualized by gastroscopy, while oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography could clearly display and diagnose these tumors.

In summary, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography has several advantages compared to gastroscopy. It is simple, safe, and minimally invasive for detecting gastric tumors, and is suitable for feeble and sick patients who cannot tolerate gastroscopy. For patients with anemia or abdominal dull pain, as well as thin patients, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography can be the preferred method for screening gastric tumors. In addition to the staging of middle or advanced stage gastric cancer, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography can also detect the metastases in peripheral and distal organs, which cannot be achieved by gastroscopy. Therefore, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography can avoid unnecessary exploratory surgical laparotomy, and provide reliable evidence for diagnosis and treatment of gastric tumors in clinical practice. The combined application of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and electronic gastroscopy could improve the accuracy rate of the diagnosis of gastric tumors, provide more reliable evidence for the diagnosis, treatment, and outcome prediction of gastric tumors, and has guiding significance in clinical practice.

The incidence of gastric cancer remains high, and it is the sixth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. Oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography is a simple, non-invasive, and painless method for the diagnosis of gastric tumors.

The authors found that oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography can avoid unnecessary exploratory surgical laparotomy, and provide reliable evidence for diagnosis and treatment of gastric tumors in clinical practice.

This study aimed to explore the diagnostic value of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the detection of gastric tumors.

In this study, a total of 42 gastric tumor patients underwent both oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and gastroscopy. The screening results based on oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and electronic gastroscopy were compared with those of the postoperative pathological examination.

Among 42 patients with gastric tumors enrolled in the study, the diagnostic accordance rate was 95.2% for oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, and 90.5% for electronic gastroscopy compared with postoperative pathological examination. The Kappa value of consistency test with pathological findings was 0.812 for oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and 0.718 for electronic gastroscopy, and there was no significant difference between them.

In summary, oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography has several advantages compared to gastroscopy. It is simple, safe, and minimally invasive for detecting gastric tumors, and is suitable for feeble and sick patients who cannot tolerate gastroscopy. The accordance rate of qualitative diagnosis by oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography was comparable to that of gastroscopy, and it could be used as the preferred method for the early screening of gastric tumors.

The combined application of oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and electronic gastroscopy could improve the accuracy rate of the diagnosis of gastric tumors, provide more reliable evidence for the diagnosis, treatment, and outcome prediction of gastric tumors, and has guiding significance in clinical practice.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Seide SE, Germany; Siargkas A, United Kingdom S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Wang LA, Wei X, Li Q, Chen L. The prediction of survival of patients with gastric cancer with PD-L1 expression using contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:7327-7332. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50630] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45422] [Article Influence: 15140.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (47)] |

| 3. | Willis S, Truong S, Gribnitz S, Fass J, Schumpelick V. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the preoperative staging of gastric cancer: accuracy and impact on surgical therapy. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:951-954. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 110] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Badea R, Neciu C, Iancu C, Al Hajar N, Pojoga C, Botan E. The role of i.v. and oral contrast enhanced ultrasonography in the characterization of gastric tumors. A preliminary study. Med Ultrason. 2012;14:197-203. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Habermann CR, Weiss F, Riecken R, Honarpisheh H, Bohnacker S, Staedtler C, Dieckmann C, Schoder V, Adam G. Preoperative staging of gastric adenocarcinoma: comparison of helical CT and endoscopic US. Radiology. 2004;230:465-471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 204] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yu T, Wang X, Zhao Z, Liu F, Liu X, Zhao Y, Luo Y. Prediction of T stage in gastric carcinoma by enhanced CT and oral contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:184. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu Z, Guo J, Wang S, Zhao Y, Li J, Ren W, Tang S, Xie L, Huang Y, Sun S, Huang L. Evaluation of transabdominal ultrasound after oral administration of an echoic cellulose-based gastric ultrasound contrast agent for gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:932. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li S, Huang P, Wang Z, Chen J, Xu H, Wang L, Zhang Y, Mo G, Zhu J, Cosgrove D. Preoperative T staging of advanced gastric cancer using double contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33:E218-E224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yan C, Bao X, Shentu W, Chen J, Liu C, Ye Q, Wang L, Tan Y, Huang P. Preoperative Gross Classification of Gastric Adenocarcinoma: Comparison of Double Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound and Multi-Detector Row CT. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:1431-1440. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shi H, Yu XH, Guo XZ, Guo Y, Zhang H, Qian B, Wei ZR, Li L, Wang XC, Kong ZX. Double contrast-enhanced two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasonography for evaluation of gastric lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4136-4144. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Suk KT, Lim DW, Kim MY, Park DH, Kim KH, Kim JM, Kim JW, Kim HS, Kwon SO, Baik SK, Park SJ. Thickening of the gastric wall on transabdominal sonography: a sign of gastric cancer. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36:462-466. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Neciu C, Badea R, Chiorean L, Badea AF, Opincariu I. Oral and I.V. contrast enhanced ultrasonography of the digestive tract--a useful completion of the B-mode examination: a literature review and an exhaustive illustration through images. Med Ultrason. 2015;17:62-73. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu Z, Guo J, Wang S, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Li J, Ren W, Tang S, Xie L, Huang Y, Sun S, Huang L. Evaluation of Transabdominal Ultrasound with Oral Cellulose-Based Contrast Agent in the Detection and Surveillance of Gastric Ulcer. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:1364-1371. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sano T, Coit DG, Kim HH, Roviello F, Kassab P, Wittekind C, Yamamoto Y, Ohashi Y. Proposal of a new stage grouping of gastric cancer for TNM classification: International Gastric Cancer Association staging project. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:217-225. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 302] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang FH, Zhang XT, Li YF, Tang L, Qu XJ, Ying JE, Zhang J, Sun LY, Lin RB, Qiu H, Wang C, Qiu MZ, Cai MY, Wu Q, Liu H, Guan WL, Zhou AP, Zhang YJ, Liu TS, Bi F, Yuan XL, Rao SX, Xin Y, Sheng WQ, Xu HM, Li GX, Ji JF, Zhou ZW, Liang H, Zhang YQ, Jin J, Shen L, Li J, Xu RH. The Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO): Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer, 2021. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41:747-795. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 315] [Article Influence: 105.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Leung WK, Wu MS, Kakugawa Y, Kim JJ, Yeoh KG, Goh KL, Wu KC, Wu DC, Sollano J, Kachintorn U, Gotoda T, Lin JT, You WC, Ng EK, Sung JJ; Asia Pacific Working Group on Gastric Cancer. Screening for gastric cancer in Asia: current evidence and practice. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:279-287. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 578] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 642] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liu L, Lu DY, Cai JR, Zhang L. The value of oral contrast ultrasonography in the diagnosis of gastric cancer in elderly patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pei F, Liu Y, Zhang F, Li N, Huang D, Gu B. Cholecystoduodenal fistula: ultrasonographic diagnosis with oral gastrointestinal ultrasound contrast medium. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:561-564. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ishigami S, Yoshinaka H, Sakamoto F, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, Nakajo A, Matsumoto M, Okumura H, Hokita S, Aikou T. Preoperative assessment of the depth of early gastric cancer invasion by transabdominal ultrasound sonography (TUS): a comparison with endoscopic ultrasound sonography (EUS). Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1202-1205. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Polkowski M, Palucki J, Butruk E. Transabdominal ultrasound for visualizing gastric submucosal tumors diagnosed by endosonography: can surveillance be simplified? Endoscopy. 2002;34:979-983. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shen L, Zhou C, Liu L, Zhang L, Lu D, Cai J, Zhao L, Chu R, Zhou J, Zhang J. Application of oral contrast trans-abdominal ultrasonography for initial screening of gastric cancer in rural areas of China. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:918-923. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hyun JJ, Yeom SK, Shim E, Cha J, Choi I, Lee SH, Chung HH, Cha SH, Lee CH. Correlation Between Bile Reflux Gastritis and Biliary Excreted Contrast Media in the Stomach. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2017;41:696-701. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zheng XZ, Zhang LJ, Wu XP, Lu WM, Wu J, Tan XY. Oral Contrast-Enhanced Gastric Ultrasonography in the Assessment of Gastric Lesions: A Large-Scale Multicenter Study. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:37-47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tiao MM, Ko SF, Hsieh CS, Ng SH, Liang CD, Sheen-Chen SM, Chuang JH, Huang HY. Antral web associated with distal antral hypertrophy and prepyloric stenosis mimicking hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:609-611. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Eldredge TA, Myers JC, Kiroff GK, Shenfine J. Detecting Bile Reflux-the Enigma of Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28:559-566. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |