INTRODUCTION

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is one of the challenging situations in clinical practice due to its etiology, location, types of bleeding, and severity. It comprises of non-variceal and variceal bleeding[1,2]. In the past, there has been no significant change from time to time regarding the etiology of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB). Gastric ulcer (GU) and duodenal ulcer (DU) are still the main causes of acute NVUGIB, where hemorrhage and perforation are the major causes for mortality[3,4]. A recent large multicenter study showed that the bleeding etiology for NVUGIB was dominated by DU, followed by GU, whereas neoplasia was ranked as the fourth common cause of NVUGIB when compared to other non-malignant causes, such as Mallory-Weiss, esophagitis, and Dieulafoy’s lesion. Recurrent bleeding was found in 3.2% of patients, with a 4.5% mortality rate in 30 d. Standard endoscopic treatment, which consists of injection, thermal coagulation, hemoclips, and combination therapy, has shown a good bleeding control rate. However, endoscopic treatment failure was still found to be higher in patients with several predictors, such as in-hospital bleeding, hematemesis, renal failure, neoplasia, and liver cirrhosis[5]. Recently, there has been innovation management using endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for managing variceal bleeding as it can target the bleeding vessel much better than conventional endoscopic management[6]. Therefore, in this review, the role of EUS will be discussed further.

METHODS

We collected all articles which have been published on standard endoscopic management as well as endoscopic ultrasound guided management in UGIB through the Medline/PubMed databases. The keywords used were EUS-guided vascular therapy, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The purpose of this review was to elaborate the standard endoscopic management, limitations, new development or technique innovation, bleeding causes, and patient’s outcome.

ENDOSCOPIC MANAGEMENT FOR NON-VARICEAL UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Standard endoscopic hemostasis treatment for NVUGIB consists of drug injection (epinephrine, cyanoacrylate, and other sclerosing agents), thermal coagulation, mechanical method, as well as topical treatment[7]. Endoscopic findings and bleeding ulcer stratification based on Forrest class have been routinely used as a standard parameter for the decision of endoscopic treatment options. Based on the Forrest classification, active bleeding (classes IA and B) has a 55% rebleeding rate with a 11% mortality rate, followed by visible vessel (class IIA) with a 43% rebleeding rate and 11% mortality rate, adherent clot (class IIB) with a 22% rebleeding rate and 7% mortality rate, flat spot (class IIC) with a 10% rebleeding rate and 3% mortality rate, and clean base ulcer (class III) with a 5% rebleeding rate and 2% mortality rate[8]. A randomized controlled trial by Chau et al[9] looking at the role of epinephrine injection combined with heat probe coagulation therapy vs epinephrine injection combined with argon plasma coagulation treatment in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers showed no significant difference between the two combined methods in achieving successful hemostasis (95.9% vs 97.7%). This study mostly included patients with Forrest classes IB and IIA. However, the rebleeding rate from both of groups was still high (21.6% and 17.0%), and the hospital mortality was 6.2% and 5.7%, respectively. Another randomized controlled trial by Lo et al[10] showed that combined therapy using epinephrine injection with hemoclip therapy vs epinephrine injection alone was more effective in reducing the rebleeding rate (100% vs 33%, P = 0.02). In fact, no surgery was even required in the combination treatment group when compared to the single treatment group (P = 0.023). The use of clips in NVUGIB might be associated with less mucosal injury when compared to thermal therapy[11]. In 2010, a novel endoscopic method using electrocautery forceps alone or with combined method based on retrospective multicenter data from patients with nonmalignant gastroduodenal ulcer bleeding in Japan showed that the rate of successful bleeding control was achieved in 96.8% of peptic ulcer patients, and 100% of artificial ulcer patients. However, there were 12 patients with rebleeding, which consisted of seven (11.5%) peptic ulcer patients and five (7.6%) artificial ulcer patients. In the rebleeding management, only one patient needed repeat endoscopic hemostasis treatment, and one patient required surgery after undergoing combination treatment. However, this study has been limited by the patient’s selection bias as well as the endoscopist’s procedure skill[12]. Another innovation on endoscopic management on UGIB using a novel hemostatic powder (the “GRAPHE” registry), TC-325, showed that the immediate bleeding control effect was achieved by 96.5% of the patients; however, recurrent bleeding was found in 26.7% of patients at day 8 and 33.5% at day 30. Melena and pulsatile bleeding were the two most important factors for recurrent bleeding[13]. A large multicenter prospective study by Kawaguchi et al[14] showed that the most frequent cause of NVUGIB was gastric ulcer (GU; 69%), followed by DU (27%) and gastroduodenal ulcer (4%). The in-hospital 4-wk mortality rate was 5%, where two patients who died were associated with the bleeding itself. Patients with DU had a significantly higher mortality rate when compared to patients with GU (16% vs 4%, P = 0.014). In this study, 20 patients (8%) had unsuccessful endoscopic treatment. Other factors were comorbidities, the use of antithrombotic agent, and in-hospital onset. Based on the guideline recommendations from the international consensus group for NVUGIB management, it has been suggested that TC-325 can become a temporary treatment option with low evidence. This is due to its high rebleeding rates after 72 h and 1 wk. Endoscopic treatment, such as epinephrine injection, thermal coagulation, and clipping, is still considered as the main treatment. However, there was no significant difference in term of mortality rate even with combination therapy[15].

ENDOSCOPIC ULTRASOUND EVOLUTION AND INNOVATION IN MANAGING NON-VARICEAL UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

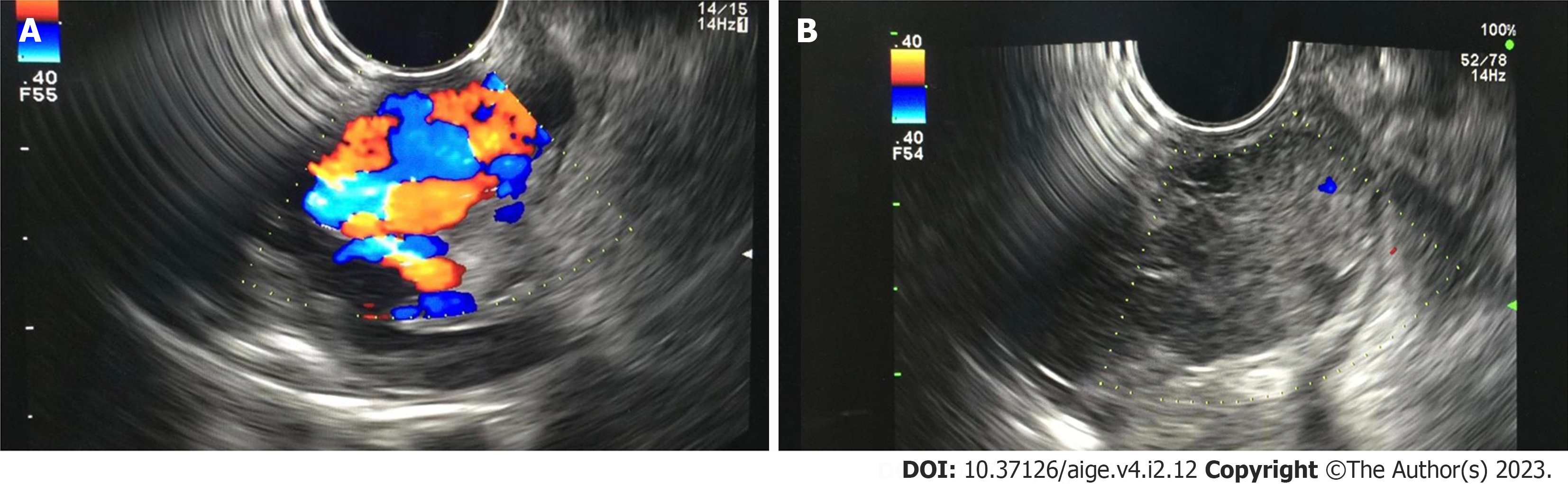

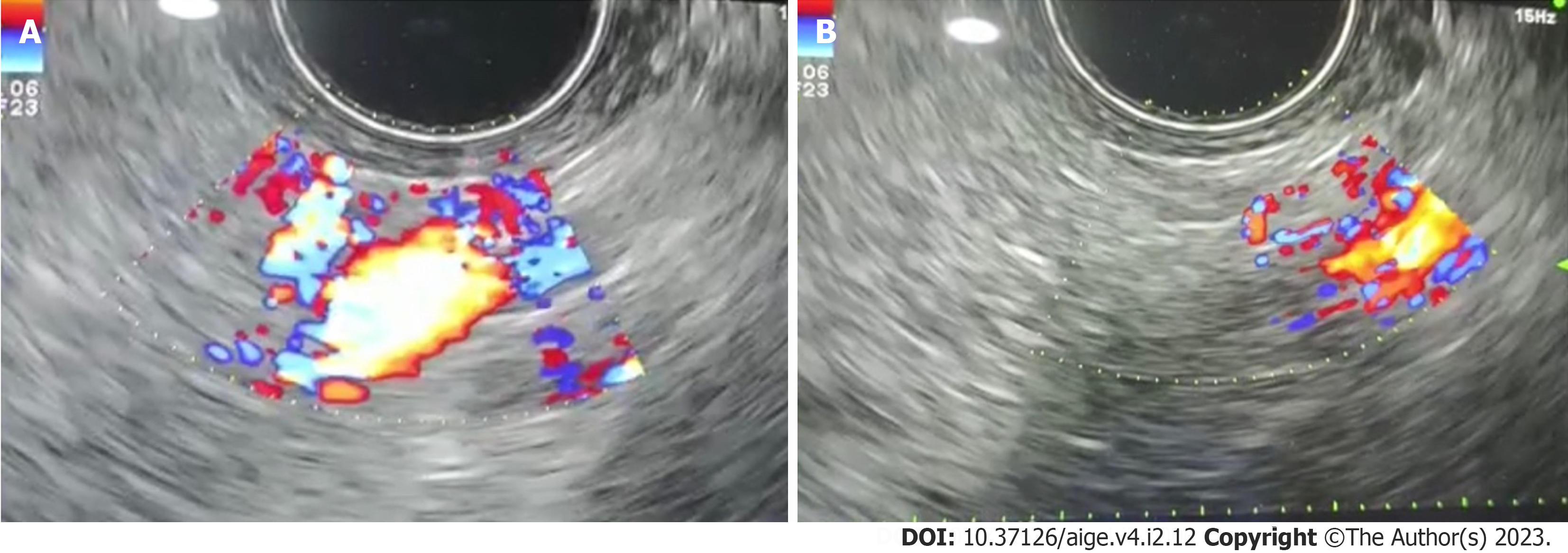

In the evolution of therapeutic EUS development, a pioneer study by Boustière et al[16] performed EUS in liver cirrhotic patients, where gastric varices could be identified and stratified much better than esophageal varices. All cases suspected with the presence of GV was confirmed by EUS examination. In 2000, Lee et al[17] published a study on EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection for bleeding GV showed that repeated injection under EUS guidance might improve patient survival as the recurrent bleeding incidence was decreased significantly when compared to on-demand treatment. Another small case series study by Romero-Castro et al[18] showed successful EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection for the perforating veins related to GV. These innovation studies also have been supported by a recent acute variceal bleeding case series study[19], which concluded that EUS can give accurate approach in varices treatment (Figure 1). In 2011, a study by Binmoeller et al[20] showed that EUS-guided transesophageal combined treatment using coil and cyanoacrylate for GV management achieved a success in all cases. The rebleeding was noted to be not associated with the variceal bleeding. This was followed and supported by a recent study published by Bick et al[21], where they showed that by using EUS, the GV can be covered in a larger number when compared to the standard endoscopic injection. In fact, the use of EUS for NVUGIB management also has been studied in the past; however, most of them were only case report studies[22]. The first well-known case series study was published in 1996, which described the use of EUS examination for Dieulafoy’s lesion evaluation and management. Three patients underwent sclerotherapy injection using 1% polidocanol under EUS guidance successfully without any adverse events[23]. This study was supported by other two case reports in patients who experienced bleeding due to Dieulafoy’s lesion. One case report described the treatment using thermal contact with 7F Bicap probe (Boston Scientific). This probe was passed through the EUS channel combined with 2.5 mL absolute alcohol, which resulted in deep mucosal thermal burn, thus reducing the amplitude of arterial wave form. Another case underwent endoscopic band ligation after EUS evaluation. There was no rebleeding after the first procedure in both cases[24,25]. In 2008, Levy et al[26] published a study on EUS-guided angiotherapy for refractory NVUGIB, which consisted of bleeding due to hemosuccus pancreaticus, Dieulafoy’s lesion, DU, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), and occult GI bleeding. In this case series study, absolute alcohol injection was performed for hemosuccus pancreaticus bleeding and Dieulafoy’s lesion, and cyanoacrylate injection for DU and GIST patients. All patients in this study did not have any rebleeding episodes, even after more than 12 mo. A larger case series study by Law et al[27] on the use of EUS-guided hemostasis treatment in patients with resistant non-variceal bleeding (GIST, colorectal vascular malformations, duodenal masses or polyps, Dieulafoy’s lesions, DUs, and rectally invasive prostate cancer), showed that the complete vascular cessation was achieved in 63% of patients and the flow decrease in 37% of patients. There were no adverse events observed after the procedure. No patients had rebleeding within 12 mo follow-up after the procedure. Two studies reported only bleeding due to pancreatic pseudoaneurysm. One study reported a patient with chronic pancreatitis and splenic vein thrombosis with portal hypertension, who underwent EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy for biliary tract stones. The late bleeding was due to the presence of pseudoaneurysm close to the pancreatic pseudocyst drainage area. The bleeding was controlled with n-butyl cyanoacrylate injection under EUS guidance. No recurrent bleeding was observed after the hemostatic procedure. The other case was a patient experiencing pseudoaneurysm induced by hemosuccus pancreaticus which has been confirmed by computed tomography angiography. This patient underwent EUS-guided coil embolization. No bleeding was recorded after more than a year[28,29]. The role of EUS-guided vascular therapy also has been reported in visceral pseudoaneurysm. The first case was reported by Lameris et al[30], where a thrombin-collagen compound was injected into pseudoaneurysm and the Doppler study revealed complete obliteration. No rebleeding occurred during 10 mo follow-up. Sharma et al[31] reported bleeding from visceral pseudoaneurysm due to acute pancreatitis, and it was successfully controlled by human thrombin injection. A recent single-blind study by Jensen et al[32] in 148 patients with severe NVUGIB who underwent endoscopic hemostasis under Doppler guidance showed that the rebleeding rate was significantly lower when compared to the control group (11.1% vs 26.3%, P = 0.0214). However, the use of EUS with Doppler guidance would give more accuracy and advantage to detect the bleeding source and manage severe NVUGIB due to possible poor visualization during standard endoscopic hemostasis procedure (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Gastric varices images before and after endoscopic ultrasound guided cyanoacrylate injection.

A: Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) image of large gastric varices; B: EUS image of gastric varices post cyanoacrylate injection. Endoscopy database Medistra Hospital, Jakarta.

Figure 2 Deep vascular bleeding source detection through endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and after EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection.

A: Deep vascular bleeding source detection based on endoscopic ultrasound (EUS); B: EUS image after cyanoacrylate injection to control the bleeding source. Endoscopy database Medistra Hospital, Jakarta.

CONCLUSION

NVUGIB is still a challenging situation where there are a variety of causes which sometimes cannot be detected through standard endoscopic examination. EUS has shown that it has an important role in managing UGIB, especially in NVUGIB. However, it still needs larger study before it can be recommended as the first-line approach in managing NVUGIB.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology & hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Indonesia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rodrigo L, Spain S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Cai YX