Published online Jun 28, 2020. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v8.i3.245

Peer-review started: February 13, 2020

First decision: February 26, 2020

Revised: May 15, 2020

Accepted: June 10, 2020

Article in press: June 10, 2020

Published online: June 28, 2020

Processing time: 144 Days and 19.9 Hours

Little information has been published on the risks of cigar smoking. Since 1990 cigar smoking has become more prevalent in the United States.

To summarise the evidence from the United States relating exclusive cigar smoking to risk of the major smoking-related diseases.

Literature searches detected studies carried out in the United States which estimated the risk of lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, stroke or overall circulatory disease in exclusive cigar smokers as compared to those who had never smoked any tobacco product. Papers were identified from reviews and detailed searches on MEDLINE. For each study, data were extracted onto a study database and a linked relative risk database. Relative risks and 95%CIs were extracted, or estimated, relating to current, former or ever exclusive cigar smokers, and meta-analysed using standard methods. Sensitivity analyses were conducted including or excluding results from studies that did not quite fit the full selection criteria (for example, a paper presenting combined results from five studies, where 86% of the population were in the United States).

The literature searches identified 17 relevant publications for lung cancer, four for COPD and 12 for heart disease, stroke and circulatory disease. These related to 11 studies for lung cancer, to four studies for COPD and to eight studies for heart disease, stroke or overall circulatory disease. As some studies provided results for more than one disease, the total number of studies considered was 13, with results from four of these used in sensitivity analyses. There was evidence of significant heterogeneity in some of the meta-analyses so the random-effects estimates are summarized below. As the results from the sensitivity analyses were generally very similar to those from the main analyses, and involved more data, only the sensitivity results are summarized below. For lung cancer, relative risks (95%CI) for current, former and ever smokers were respectively, 2.98 (2.08 to 4.26), 1.61 (1.23 to 2.09), and 2.22 (1.79 to 2.74) based on 6, 4 and 10 individual study estimates. For COPD, the corresponding estimates were 1.44 (1.16 to 1.77), 0.47 (0.02 to 9.88), and 0.86 (0.48 to 1.54) based on 4, 2 and 2 estimates. For ischaemic heart disease (IHD) the estimates were 1.11 (1.04 to 1.19), 1.26 (1.03 to 1.53) and 1.15 (1.08 to 1.23) based on 6, 3 and 4 estimates, while for stroke they were 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13), 1.08 (0.85 to 1.38), and 1.11 (0.95 to 1.31) based on 5, 3 and 4 estimates. For overall circulatory disease they were 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16), 1.11 (0.84 to 1.46), and 1.15 (1.06 to 1.26) based on 3, 3 and 4 estimates.

Exclusive cigar smoking is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer, and less so with COPD and IHD. The increases are lower than for cigarettes.

Core tip: Thirteen studies in the United States presented evidence relating exclusive cigar smoking to risk of lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and/or circulatory disease. Compared to never smokers, current exclusive cigar smoking increased risk of lung cancer about three-fold, COPD by about 40% and heart disease by about 10% but did not increase risk of stroke. These increases are much lower than those for cigarette smoking.

- Citation: Lee PN, Hamling JS, Thornton AJ. Exclusive cigar smoking in the United States and smoking-related diseases: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal 2020; 8(3): 245-264

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v8/i3/245.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v8.i3.245

There is extensive evidence on the relationship of cigarette smoking to health endpoints but far less evidence relating to cigar smoking. While some studies have reported results relating to dual use of cigars and pipes[1-4] or to cigar smoking in those who may also smoke other tobacco products[5], the health effects of exclusive cigar smoking have been less often reported. Comparing disease risk in cigar smokers who have never smoked other tobacco products with that in never smokers of any tobacco product avoids the problems of residual confounding by other smoking habits and of possible differences in cigar smoking habits (such as depth of inhalation[6]) in those who have ever smoked other tobacco products.

Exclusive cigar smoking is much less common than cigarette smoking so the population studied must be large enough to include enough exclusive cigar smokers for a useful risk assessment to be made. For this reason we have restricted attention to studies in the United States, a country not only with a large population, but one where cigar smoking is relatively common compared with other countries[7,8]. We also restrict attention to the major smoking-related diseases.

Published studies were included if they were carried out in the United States and reported the risk of lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or heart disease, stroke and/or overall circulatory disease, comparing exclusive cigar smokers (current, former or ever cigar smokers who never smoked other tobacco products) with never smokers of any tobacco (or a closely-related comparison group). The results considered were for overall lung cancer rather than lung cancer subtypes, and related to overall risk measures rather than dose response indices, although dose response results by amount smoked were also identified.

Searching for results on cigar smoking was complicated by the MEDLINE search term “cigar smoking” being available only from the start of 2018. Before then the only search term to include cigar smoking was “tobacco products”.

For lung cancer, the first step was to examine publications from a previous review relating lung cancer to various indices of smoking based on studies published during the 1900s[9]. Subsequently three different MEDLINE searches were conducted using terms such as (“cigar” or “cigars”), “United States” and “lung neoplasms”. This was followed by a fourth search that attempted to retrieve relevant papers that had not yet been indexed with MeSH terms on MEDLINE, this search not being lung cancer specific. A fifth search used wholly non-MeSH search terms, with the final stage being to look for relevant results in papers identified as relevant in the searches for COPD and for heart disease, stroke and circulatory diseases.

For COPD, the process started with three different MEDLINE searches using the terms “COPD” or “pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive” to identify the disease. The fourth search used the term “Smoking” rather than “Cigar”, while the fifth search used the MeSH terms “Smoking/mortality” or “Smoking/adverse effects”. The next step was to review the results from the fourth lung cancer search, while the final step was to look at papers identified as relevant in the searches for lung cancer and for heart disease, stroke and circulatory diseases.

For heart disease, stroke and circulatory diseases, the process started with four different MEDLINE searches using the disease terms “Heart disease”, “Stroke” or “Heart”. The next step was again to review the results from the fourth lung cancer search, while the final step was to look at relevant papers from the lung cancer and COPD searches.

Searching ended when no new data was found and all the papers referenced by reviews had been examined. Full details of the searches are given in Supplementary material.

The papers identified in the searches were reviewed for the studies they reported, and multiple publications reporting the same study were identified.

The source papers identified as providing relevant estimates were then considered for overlap of reporting. Where more than one of the source papers reported on the same study, the results may have been reported in different ways or for different lengths of follow-up, or have combined results from multiple studies.

For each paper identified as providing relevant results details were entered onto a study database and a linked relative risk (RR) database for the relevant disease.

The study database contained a record for each study describing the following aspects: A study name based on the published study name or on the name of the first author of the paper; study title; study design; sexes considered; age range and other details of the population studied; timing and length of follow-up; details of overlaps or links with other studies; number of cases; number of controls or subjects at risk; types of controls and matching factors used in case-control studies; and confounding variables considered.

The RR database holds the detailed results, typically containing multiple records for each study. Each record is linked to the relevant study via the study name, and holds details of a specific risk estimate. It records the type of estimate, its value and confidence interval, its source and other details such as the age range included in the estimate if this is different from the overall study age range. Some estimates were taken directly from the source paper. Others were derived using the details provided in the paper.

Where no RR estimate was given or a RR estimate was given without a confidence interval, information on the sample size and the number of deaths was used to estimate these. Estimates for separate independent subsets of the population such as age groups were combined using simple meta-analysis. Non-independent RRs using a common comparison group (e.g., never smokers) were combined using the Hamling method[10]. This method was used to combine RRs by number of cigars smoked per day and to combine RRs for former and current smokers to give an estimate for ever smokers. It was also used to estimate risk for overall circulatory disease when the study provided separate estimates for cerebrovascular disease and a broad definition of coronary heart disease, and to estimate overall stroke from separate risk estimates for ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. The International Classification of Disease codes used to define IHD, stroke and circulatory disease can be found at https://coder.aapc.com/icd-10-codes-range/110.

Each extract was carried out by one of the authors, the entered data and any additional calculations then being reported and checked by another of the authors, with problems discussed and amendments made until both agreed that the data entered were a true representation of the study data.

Dose-response data on risk by number of cigars smoked per day were also identified and are discussed below.

For each disease considered, fixed-effect and random-effects meta-analyses were conducted using the Fleiss and Gross method[11], with heterogeneity quantified by H, the ratio of the heterogeneity to its degrees of freedom, which is directly related to the I2 statistic[12] by the formula I2 = 100 (H-1)/H.

Whenever more than one paper provided equivalent results for a study, only one result was included in a meta-analysis. The selection of the result was based on four criteria: Prospective follow-up was given preference over cross-sectional analysis at baseline; the longest follow-up reported (for prospective studies); the widest age range reported; and finally the RR adjusted for the most confounding factors.

Some papers provided results for comparisons that did not exactly match our selection criteria. Where any were relevant to a meta-analysis, the analysis was performed excluding those results, and then including them in a sensitivity analysis.

The KAISER study[13] used a questionnaire that asked about the participant’s history of cigarette smoking and their current pipe and cigar smoking. Ever cigarette smokers were excluded from their analyses. It was, therefore, possible to identify participants who had never smoked cigarettes and who did not, at baseline, smoke cigars or a pipe. This is not completely equivalent to our requirement for the comparison group to be never smokers of any tobacco product. Also, the participants categorised as current cigar smokers may have included former pipe smokers. However, the study was large (1546 current cigar smokers and 16228 never cigarette smokers) and had a long follow-up (25-26 years) so justified inclusion in sensitivity analyses.

For the MALHOT study a pooled analysis of data from five large prospective studies was reported[14]. Of these studies, two (the Netherlands Cohort Study and the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study) were conducted outside the United States, while the other three (the VITamins And Lifestyle study, the NIH-AARP Diet and Health study and the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial) were conducted in the United States. However, the studies in the United States were larger and formed 85.7% of the total population reported, and the largest of the studies (NIH-AARP) followed up participants for a median of 15.5 years. The size of this pooled analysis, the large proportion of participants from the United States, the long follow-up in the largest study, and the lack of study-specific reports relating to cigar smoking for the studies pooled justified including the combined results in sensitivity analysis.

For the NHIS study, a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data[15] reports results for a definition of “Heart conditions” including angina, coronary heart disease, heart attack and other heart disease which is too broad for the results to be included in our main analysis of ischaemic heart disease (IHD). However, as the report considers data from four years’ surveys of this large, repeated, nationally representative study, and as no other source was found that reported IHD for this study, it was decided to include its results in sensitivity analysis.

Also for the NHIS study, an analysis of prospective findings from six years’ survey data with follow up for at least five years, the source publication[16] reports results for a broad definition of coronary heart disease which includes rheumatic fever, some hypertensive heart disease, IHD and some other heart disease. Though this definition is too broad to be included in our analyses of IHD, the paper also reports results for cerebrovascular disease (stroke), and taken together, the definitions of coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease were very close to our ideal definition of circulatory disease. We therefore combined the results for coronary heart disease and for cerebrovascular disease, and included the resulting estimates in the sensitivity analyses for overall circulatory disease.

The NLMS study[17] reported too broad a definition of cardiovascular disease, an ideal definition of stroke and a definition of circulatory disease that included all the relevant disease categories except diseases of the veins and other diseases of the circulatory system. The reported results for stroke were included in the main meta-analyses and the results for circulatory disease were included in sensitivity analysis only.

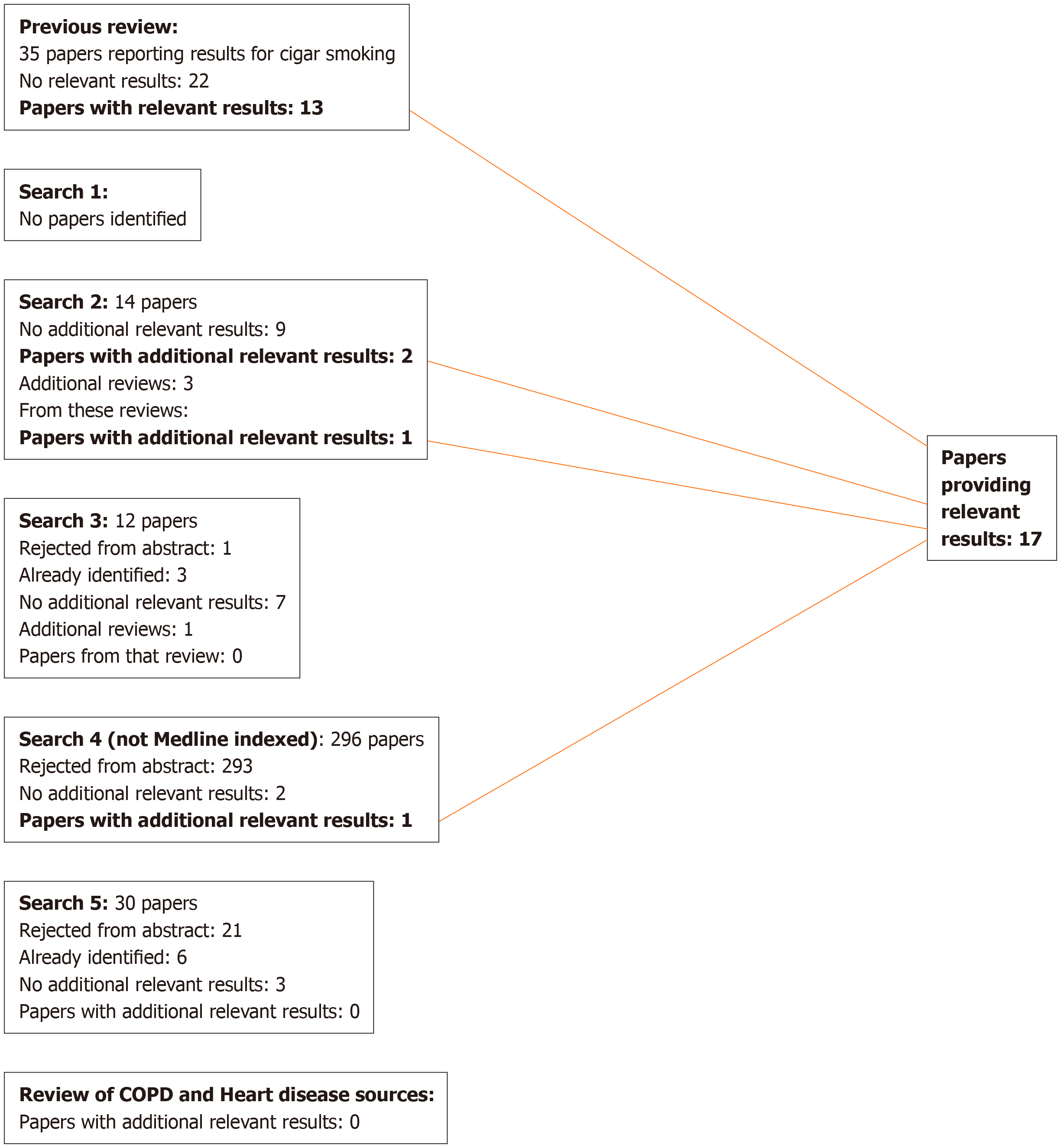

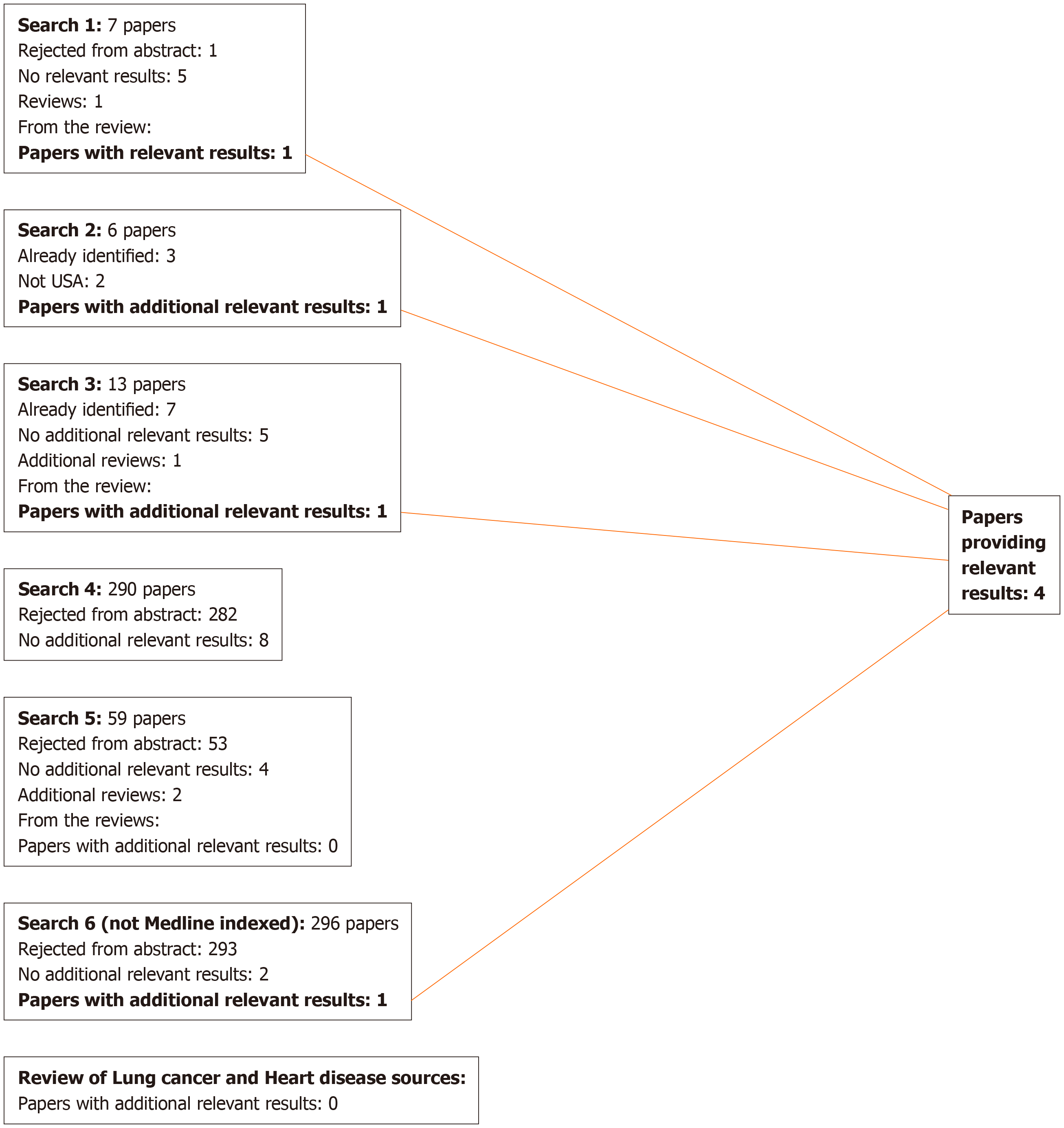

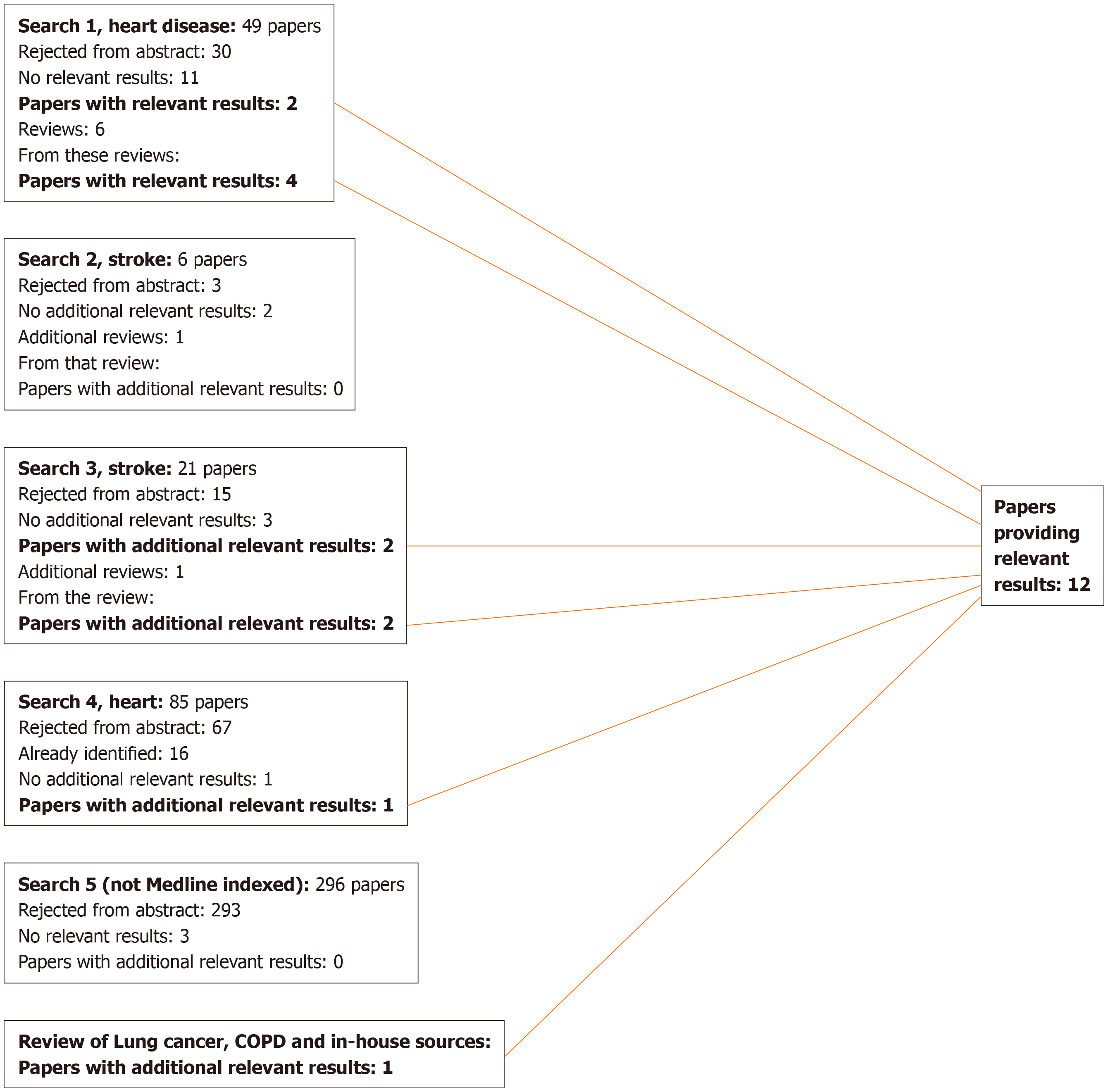

For lung cancer, 17 publications were identified that were relevant to the meta-analyses (including the sensitivity analyses), 13 from the previous review[9], three from additional searches, and one from reviews identified in the searches, as shown in Figure 1. Two of these[18,19] are by the same authors reporting the same study, the first giving overall study information and the second giving results by disease, so only the latter is cited in the analysis results. For COPD, four publications were identified (Figure 2), while for heart disease, stroke and circulatory disease 12 were found (Figure 3).

Table 1[13,14,17-31] (lung cancer), Table 2[13,17,23,27] (COPD), and Table 3[13,15-17,19,21,23,26-28,32,33] (heart disease, stroke and circulatory disease) present details on each study, including its name, the source publications, the study type, the years of follow-up, the study size, and the sexes and age groups considered. Results used in sensitivity analyses only are marked with an asterisk. Table 3 also includes details of the definition of heart disease, stroke and circulatory diseases.

| Study name2 | Data source | Study type | Years of follow-up3 | Sex | Age group | Study size4 |

| BOUCOT | Boucot et al[20], 1972 | P | 10 | M | 45+ | 6027 |

| CPS I | Hammond[21], 1966 | P | 4 | M | 35-84 | 4405585 |

| Hammond[22], 1972 | P | 6 | M | 35-84 | ||

| Shanks et al[23], 1998 | P | 13 | M | 35+ | ||

| CPS II | Jacobs et al[24], 1999 | P | 12 | M | 30+ | 5085766 |

| Shapiro et al[25], 2000 | P | 12 | M | 30+ | ||

| DORN (US veterans study) | Dorn[26], 1959 | P | 2 | M | 30+ | 2480467 |

| Kahn[27], 1966 | P | 8 | M | 35-84 | ||

| Rogot et al[28], 1980 | P | 16 | M | 31-84 | ||

| HAMMON | Hammond et al[18,19], 1958 | P | 3 | M | 50-69 | 187783 |

| KAISER | Iribarren et al[13], 1999 | P | 25 | M | 30-85 | 17774 |

| LEVIN | Levin[29], 1954 | C | - | M | 35+ | 2855 |

| MALHOT | Malhotra et al[14], 2017 | P | 15 | M | 55-62 | 5244408 |

| NLMS | Christensen et al[17], 2018 | P | 26 | C | 35-80 | 146529 |

| SADOWS | Sadowsky et al[30], 1953 | C | - | M | All | 2605 |

| WYNDE7 | Higgins et al[31], 1988 | C | - | M | 20-80 | 60339 |

| Study name2 | Data source | Study type | Years of follow-up3 | Sex | Age group | Study size4 | Disease data available and notes5 |

| CPS I | Hammond[21], 1966 | P | 4 | M | 35-84 | 4405586 | IHD: CHD (ICD-6 420); Stroke: -; Circ: - |

| Shanks et al[23], 1998 | P | 13 | M | 35+ | IHD: CHD; Stroke: CVD; Circ: - | ||

| CPS II | Jacobs et al[32], 1999 | P | 9 | M | 30+ | 508576 | IHD: CHD; Stroke: -; Circ: - |

| DORN (US veterans study) | Dorn[26], 1959 | P | 2 | M | 30+ | 2480466 | IHD: -; Stroke: -; Circ: Cardiovascular diseases (ICD-6 330-334, 400-468) |

| Kahn[27], 1966 | P | 8 | M | 35-84 | IHD: Arteriosclerotic (coronary) heart disease (ICD-6 420); Stroke: Cerebral vascular lesions (ICD-6 330-334); Circ: Total cardiovascular disease (ICD-6 330-334, 400-468) | ||

| Rogot et al[28], 1980 | P | 16 | M | 31-84 | IHD: CHD (ICD-6 420); Stroke: Stroke (ICD-6 330-334); Circ: Cardiovascular (ICD-6 330-334, 400-468) | ||

| HAMMON | Hammond et al[19], 1958 | P | 3 | M | 50-69 | 187783 | IHD: Coronary artery disease; Stroke: Cerebral vascular diseases; Circ: Heart and circulatory diseases (ICD-6 330-334, 400-468) |

| KAISER | Iribarren et al[13], 1999 | P | 25 | M | 30-85 | 17774 | IHD: CHD; Stroke: Ischaemic stroke and haemorrhagic stroke combined; Circ: - |

| KAUFMA | Kaufman et al[33], 1987 | C | - | M | 40-54 | 15067 | IHD: Non-fatal myocardial infarction; Stroke: -; Circ: - |

| NHIS | Inoue-Choi et al[16], 2019 | P | 17 | C | 18-95 | 71314 | IHD: - (“Coronary heart disease” used too broad a definition); Stroke: Cardiovascular disease (ICD-10 I60-I69); Circ: Combined “Coronary heart disease” and Stroke; this excludes some hypertensive disease, diseases of arteries and diseases of veins and other circulatory disease – included in sensitivity analysis only |

| Rostron et al[15], 20198 | X | - | C | 35+ | Not specified | IHD: Heart conditions; this includes angina, CHD, heart attack and other heart disease – included in sensitivity analysis only; Stroke: Stroke; Circ: - | |

| NLMS | Christensen et al[17], 2018 | P | 26 | C | 35-80 | 146529 | IHD: - (“Cardiovascular diseases” used too broad a definition); Stroke: Cerebrovascular disease (ICD-10 I60-I69); Circ: Circulatory disease (ICD-10 I00-I09, I20-I25, I26-I28, I29-I51, I60-I69, I70, I71, I72-I78); this definition excludes “Diseases of veins” and “Other circulatory diseases” (ICD-10 I80-I89) – included in sensitivity analysis only |

For lung cancer, the 17 publications relate to 11 studies, though two (KAISER, MALHOT) are only used in sensitivity analyses. Eight of the studies are of prospective design and three case-controls. Except for NLMS, which considers both sexes, all provide results only for males. The studies vary widely in size, with three involving over 400000 people, and four less than 10000.

For COPD, the four publications concern separate studies, though again KAISER is only used in sensitivity analyses. All the studies are prospective, with all except NLMS considering only males. All four of these studies also provide results for lung cancer. The study size in KAISER is much lower than in the other three studies.

For heart disease, stroke and circulatory disease, the 12 publications concern eight studies: Six prospective, one case-control and one reported both as a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data and using prospective follow-up. KAISER (all results), NHIS (prospective results for circulatory disease and cross-sectional results for ischaemic heart disease) and NMLS (results for circulatory disease) were only used in the sensitivity analyses. Most results were for men only, the exceptions being those from NHIS and NLMS that were for the sexes combined. As for lung cancer, the studies varied widely in size.

Overall, as many studies provided data for more than one disease, there were 13 studies, of which two only provided results for the sensitivity analyses and two others had some results restricted to sensitivity analyses.

The individual study RR estimates used are given in Table 4[13-17,19,20,22,23,25,27-33], with the results of the meta-analyses conducted summarised in Table 5. Unless otherwise stated references to combined estimates are to random-effects estimates, with 95%CI given in parentheses.

| Disease | Study name2 | Source | Exposure | Relative risk (95%CI) |

| Lung cancer | BOUCOT | [20] | Ever | 8.81 (0.45 to 170.58) |

| CPSI | [23] | Current | 3.30 (2.68 to 4.06) | |

| [22] | Ever | 2.11 (1.45 to 3.07) | ||

| CPSII | [25] | Current | 5.10 (4.00 to 6.60) | |

| [25] | Former | 1.60 (1.20 to 2.40) | ||

| [25] | Ever | 3.01 (2.42 to 3.74) | ||

| DORN | [28] | Current | 1.66 (1.18 to 2.34) | |

| [27] | Former | 1.02 (0.41 to 2.54) | ||

| [27] | Ever | 1.49 (0.97 to 2.27) | ||

| HAMMON | [19] | Ever | 1.02 (0.42 to 2.51) | |

| KAISER | [13] | Current3 | 2.14 (1.12 to 4.11) | |

| LEVIN | [29] | Ever | 1.41 (0.76 to 2.60) | |

| MALHOT | [14] | Ever3 | 2.73 (2.06 to 3.60) | |

| NLMS | [17] | Current | 3.26 (1.86 to 5.71) | |

| [17] | Former | 1.35 (0.70 to 2.61) | ||

| [17] | Ever | 2.04 (1.33 to 3.15) | ||

| SADOWS | [30] | Ever | 2.98 (1.06 to 8.33) | |

| WYNDE7 | [31] | Current | 3.15 (1.78 to 5.57) | |

| [31] | Former | 2.46 (1.27 to 4.77) | ||

| [31] | Ever | 2.83 (1.78 to 4.51) | ||

| COPD | CPSI | [23] | Current | 1.42 (0.96 to 2.03) |

| DORN | [27] | Current | 0.79 (0.31 to 2.03) | |

| [27] | Former | 1.38 (0.42 to 4.51) | ||

| [27] | Ever | 0.94 (0.43 to 2.04) | ||

| KAISER | [13] | Current3 | 1.45 (1.10 to 1.91) | |

| NLMS | [17] | Current | 2.44 (0.98 to 6.05) | |

| [17] | Former | 0.05 (0.00 to 3.19) | ||

| [17] | Ever | 0.77 (0.32 to 1.87) | ||

| IHD | CPSI | [23] | Current | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.11) |

| CPSII | [32] | Current | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.34) | |

| [32] | Former | 1.07 (0.93 to 1.24) | ||

| [32] | Ever | 1.09 (0.98 to 1.22) | ||

| DORN | [28] | Current | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.18) | |

| [27] | Former | 1.41 (1.25 to 1.60) | ||

| [27] | Ever | 1.13 (1.05 to 1.22) | ||

| HAMMON | [19] | Ever | 1.28 (1.13 to 1.44) | |

| KAISER | [13] | Current3 | 1.27 (1.12 to 1.45) | |

| KAUFMA | [33] | Current | 1.25 (0.58 to 2.67) | |

| NHIS | [15] | Current3 | 0.88 (0.61 to 1.27) | |

| [15] | Former3 | 1.33 (1.03 to 1.72) | ||

| [15] | Ever3 | 1.15 (0.93 to 1.41) | ||

| Stroke | CPSI | [23] | Current | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.06) |

| DORN | [28] | Current | 1.07 (0.95 to 1.21) | |

| [27] | Former | 1.14 (0.85 to 1.53) | ||

| [27] | Ever | 1.09 (0.93 to 1.29) | ||

| HAMMON | [19] | Ever | 1.33 (1.04 to 1.70) | |

| KAISER | [13] | Current3 | 1.08 (0.88 to 1.33) | |

| NHIS | [16] | Current | 1.60 (0.72 to 3.57) | |

| [16] | Former | 0.56 (0.20 to 1.57) | ||

| [16] | Ever | 0.94 (0.50 to 1.77) | ||

| NLMS | [17] | Current | 0.50 (0.21 to 1.22) | |

| [17] | Former | 1.08 (0.66 to 1.75) | ||

| [17] | Ever | 0.85 (0.55 to 1.30) | ||

| Circulatory disease | DORN | [28] | Current | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) |

| [27] | Former | 1.37 (1.24 to 1.52) | ||

| [27] | Ever | 1.13 (1.06 to 1.20) | ||

| HAMMON | [19] | Ever | 1.27 (1.15 to 1.40) | |

| NHIS | [16] | Current3 | 1.34 (0.88 to 2.06) | |

| [16] | Former3 | 0.75 (0.52 to 1.10) | ||

| [16] | Ever3 | 0.93 (0.70 to 1.24) | ||

| NLMS | [17] | Current3 | 1.11 (0.87 to 1.42) | |

| [17] | Former3 | 1.13 (0.93 to 1.38) | ||

| [17] | Ever3 | 1.12 (0.96 to 1.31) |

| Disease | Exposure | Number of studies | Relative risk (95%CI) fixed effect | Relative risk (95%CI) random effects | Heterogeneity I2(2) |

| Lung cancer | Current cigar smokers, excluding KAISER | 5 | 3.36 (2.93 to 3.84) | 3.12 (2.11 to 4.62) | 85.22 (P < 0.001) |

| Current cigar smokers, including KAISER | 6 | 3.29 (2.88 to 3.76) | 2.98 (2.08 to 4.26) | 82.65 (P < 0.001) | |

| Former cigar smokers | 4 | 1.61 (1.23 to 2.09) | 1.61 (1.23 to 2.09) | 0.00 (NS) | |

| Ever cigar smokers, excluding MALHOT | 9 | 2.35 (2.04 to 2.71) | 2.11 (1.64 to 2.72) | 54.77 (P < 0.05) | |

| Ever cigar smokers, including MALHOT | 10 | 2.43 (2.13 to 2.75) | 2.22 (1.79 to 2.74) | 51.51 (P < 0.05) | |

| COPD | Current cigar smokers, excluding KAISER | 3 | 1.42 (1.02 to 1.96) | 1.42 (0.89 to 2.26) | 29.95 (NS) |

| Current cigar smokers, including KAISER | 4 | 1.44 (1.16 to 1.77) | 1.44 (1.16 to 1.77) | 0.00 (NS) | |

| Former cigar smokers | 2 | 1.06 (0.34 to 3.31) | 0.47 (0.02 to 9.88) | 58.19 (NS) | |

| Ever cigar smokers | 2 | 0.86 (0.48 to 1.54) | 0.86 (0.48 to 1.54) | 0.00 (NS) | |

| IHD | Current cigar smokers, excluding NHIS and KAISER | 4 | 1.08 (1.04 to 1.13) | 1.08 (1.04 to 1.13) | 0.28 (NS) |

| Current cigar smokers, including NHIS and KAISER | 6 | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.14) | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.19) | 48.68 (P < 0.1) | |

| Former cigar smokers, excluding NHIS | 2 | 1.25 (1.14 to 1.38) | 1.23 (0.94 to 1.61) | 87.72 (P < 0.01) | |

| Former cigar smokers, including NHIS | 3 | 1.26 (1.16 to 1.38) | 1.26 (1.03 to 1.53) | 75.96 (P < 0.05) | |

| Ever cigar smokers, excluding NHIS | 3 | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.21) | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.26) | 51.96 (NS) | |

| Ever cigar smokers, including NHIS | 4 | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.21) | 1.15 (1.08 to 1.23) | 27.95 (NS) | |

| Stroke | Current cigar smokers, excluding KAISER | 4 | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.08) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.16) | 46.09 (NS) |

| Current cigar smokers, including KAISER | 5 | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.09) | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | 33.51 (NS) | |

| Former cigar smokers | 3 | 1.08 (0.85 to 1.38) | 1.08 (0.85 to 1.38) | 0.00 (NS) | |

| Ever cigar smokers | 4 | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.27) | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.31) | 21.80 (NS) | |

| Circulatory disease | Current cigar smokers, excluding NHIS and NLMS | 1 | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) | - | - |

| Current cigar smokers, including NHIS and NLMS | 3 | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) | 0.00 (NS) | |

| Former cigar smokers, excluding NHIS and NLMS | 1 | 1.37 (1.24 to 1.52) | - | - | |

| Former cigar smokers, including NHIS and NLMS | 3 | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.39) | 1.11 (0.84 to 1.46) | 81.92 (P < 0.01) | |

| Ever cigar smokers, excluding NHIS and NLMS | 2 | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.23) | 1.19 (1.06 to 1.33) | 72.63 (P < 0.1) | |

| Ever cigar smokers, including NHIS and NLMS | 4 | 1.15 (1.10 to 1.21) | 1.15 (1.06 to 1.26) | 51.29 (NS) |

For current smokers there was highly significant heterogeneity (P < 0.001) between the five estimates, which ranged from 1.66 (1.18 to 2.34) for DORN to 5.10 (4.00 to 6.60) for CPS II. The overall estimate was 3.12 (2.11 to 4.62). Including the result from study KAISER little affected the combined estimate, which became 2.98 (2.08 to 4.26).

The four results for former smokers showed no significant heterogeneity (at P < 0.1), and gave a somewhat lower estimate of 1.61 (1.23 to 2.09).

The nine results for ever smokers showed significant (P < 0.05) heterogeneity due to the high estimate from BOUCOT of 8.81. The rest of the estimates ranged from 1.02 to 3.01. The overall estimate was 2.11 (1.64 to 2.72). When the result from MALHOT was included, this became 2.22 (1.79 to 2.74).

None of the analyses showed significant heterogeneity, and there was very limited evidence of an association. Results were available from only four studies and for only two of these were results available for each of the exposures current, former and ever smokers (Table 4). This resulted in all the combined estimates being based on between two and four results. For current smokers the overall estimate was slightly raised at 1.42 (0.89 to 2.26) excluding KAISER and 1.44 (1.16 to 1.77) including KAISER, but no increase was seen for ever smokers 0.86 (0.48 to 1.54). For former smokers, the overall estimate of 0.47 had an extremely wide CI of 0.02 to 9.88, based on individual estimates of 0.05 (0.00 to 3.19) and 1.38 (0.42 to 4.51).

As is evident from Table 5, overall estimates generally only slightly exceeded 1.00, though some of those for IHD and circulatory disease, but not stroke, were significantly raised (at P < 0.05). There was also evidence of heterogeneity in some of the meta-analyses presented. Generally, the results from the sensitivity analyses were similar to those from the main analyses, so only the former set of results, which involve more studies, are considered below.

For ischaemic heart disease, the estimates were somewhat higher for former than current smokers, being 1.11 (1.04 to 1.19) for current smokers, 1.26 (1.03 to 1.53) for former smokers, and 1.15 (1.08 to 1.23) for ever smokers.

For stroke, the estimates were all closer to 1.00, but again somewhat higher for former than current smokers, being 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) for current smokers, 1.08 (0.85 to 1.38) for former smokers, and 1.11 (0.95 to 1.31) for ever smokers.

For overall circulatory disease, the three estimates were quite similar, being 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) for current smokers, 1.11 (0.84 to 1.46) for former smokers and 1.15 (1.06 to 1.26) for ever smokers.

Many studies did not provide data on risk by number of cigars smoked per day. Table 6[13,17,23,27,30,32,33] summarizes the limited data available from six studies, five of which provided data for ischaemic heart disease, four for lung cancer, and two for COPD. With the possible exception of the result for the SADOWS study, the data for lung cancer seemed consistent with an increasing risk with increasing amount smoked. The data for COPD and for ischaemic heart disease, however, did not consistently show any clear increase in risk with amount smoked.

| Study | Cigars per day | RR (95%CI) lung cancer | RR (95% CI) COPD | RR (95%CI) IHD | Adjustment factors |

| CPS I[23] | |||||

| 1-2 | 0.90 (0.54 to 1.66) | 1.39 (0.74 to 2.38) | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.07) | Age | |

| 3-4 | 2.36 (1.49 to 3.54) | 1.78 (0.89 to 3.18) | 1.06 (0.96 to 1.16) | ||

| 5+ | 3.40 (2.34 to 4.77) | 1.03 (0.37 to 2.23) | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.24) | ||

| CPS II[32] | |||||

| Age 30-74 years | 1 | 1.18 (0.76 to 1.82) | Age+2 | ||

| 2-3 | 1.43 (1.03 to 1.99) | ||||

| 4+ | 1.33 (0.95 to 1.86) | ||||

| Age 75+ years | 1 | 1.07 (0.64 to 1.78) | |||

| 2-3 | 0.72 (0.45 to 1.16) | ||||

| 4+ | 1.03 (0.70 to 1.51) | ||||

| DORN[27]3 | |||||

| Age 55-64 | < 5 | 0.64 (0.15 to 2.69) | 0.84 (0.70 to 1.01) | None | |

| 5+ | 3.74 (1.53 to 9.10) | 0.98 (0.78 to 1.24) | |||

| Age 65-74 | < 5 | 1.32 (0.65 to 2.69) | 1.07 (0.94 to 1.23) | ||

| 5+ | 1.83 (0.78 to 4.27) | 1.21 (1.02 to 1.45) | |||

| KAISER[13] | |||||

| < 5 | 1.57 (0.67 to 3.66) | 1.30 (0.93 to 1.81) | 1.20 (1.03 to 1.40) | Age+4 | |

| 5+ | 3.24 (1.01 to 10.40) | 2.25 (1.39 to 3.65) | 1.56 (1.21 to 2.01) | ||

| KAUFMAN[33] | |||||

| 1-4 | 0.90 (0.30 to 2.70) | Age+5 | |||

| 5+ | 1.70 (0.60 to 4.80) | ||||

| NLMS[17] | |||||

| < 1 | 0.74 (0.08 to 7.26) | Age+6 | |||

| 1+ | 4.18 (2.34 to 7.46) | ||||

| SADOW[30]7 | |||||

| 1 | 1.62 | None | |||

| 2 | 4.51 | ||||

| 3 | 4.38 | ||||

| 4+ | 2.54 | ||||

The meta-analysis results show some increase in risk among exclusive cigar smokers for each disease studied, except for stroke where all the risk estimates were close to 1. For current smoking the overall estimates in the sensitivity analyses were 2.98 for lung cancer, 1.44 for COPD and 1.11 for ischaemic heart disease. These are much lower than those associated with cigarette smoking: For the United States, estimates for current cigarette smokers[34] are 11.68 for lung cancer and 4.56 for COPD; for ischaemic heart disease[34] the current cigarette smoker estimate for age 65 to 74 is 1.70, with estimates for younger ages being higher. Even for heavy cigar smokers, the RRs shown in Table 6 are still generally lower than the estimates for overall cigarette smoking. For former smoking the estimates of 1.61 for lung cancer, 0.47 for COPD (though based on only two widely differing estimates) and 1.26 for ischaemic heart disease are again much lower than those for cigarette smoking. Similar results were observed for ever smoking.

There are some limitations with the data available for our analyses. Several of the studies were conducted some time ago. The numbers of exclusive cigar smokers participating in the studies were often quite low. Very few studies have reported results for exclusive cigar smokers. For many of these studies, cigar smoking is not the primary focus of the study. This suggests that there may be reporting bias, in that other studies may have had relevant data but did not report a non-significant finding for the study’s small number of cigar smokers.

There was a limited amount of dose-response data, and a lack of data on how risk varied by type of cigar smoked. No meta-analyses could be carried out by subgroups such as race and age and gender, as there was insufficient data. No study reported results for sex separately, so no analysis by sex could be done.

Nevertheless, the data provide fairly clear evidence that exclusive cigar smoking is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer, though less markedly than is the case for exclusive cigarette smoking. For COPD and ischaemic heart disease, the association is weaker, and is also less than that for cigarette smoking.

How do these results compare with previous estimates? It should be noted that no other review has provided meta-analysis estimates for exclusive cigar smokers in the United States, and that many of the previous reviews considered below were conducted many years ago.

The review of smoking and lung cancer[9] referred to under literature searches provided random effects meta-analysis estimates for lung cancer in current, former and ever exclusive cigar smokers of 4.67 (n = 15), 2.85 (n = 5) and 2.95 (n = 15) respectively, but these analyses were not restricted to studies in the United States. The risk estimates included in those analyses showed significant heterogeneity. A review by Wynder et al[35] considering the risk of lung cancer in pipe and cigar smokers noted that, in prospective studies in North America the mortality ratios were in the range 2 to 6. For retrospective studies, mostly conducted in Germany and Switzerland, “it appears that the risk of lung cancer is higher than that for such smokers in the United States”. This review suggested that these differences stemmed from different patterns of inhalation in the two regions. A similar review by Higgins et al[31], also considering pipe and cigar smokers, again suggested that risk estimates from prospective studies in North America are lower than those from case control studies in Europe. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9[23], reviewing data from CPS-I, stated that “Lung cancer mortality ratios increase with increasing number of cigars smoked per day and with increasing depth of inhalation. When depth of inhalation and number of cigars per day are examined together, depth of inhalation is more powerful in predicting lung cancer risk than number of cigars smoked per day.” The 1979 report by the Surgeon General[36] summarised the available evidence as “Several prospective epidemiological studies have demonstrated higher lung cancer mortality ratios for pipe and cigar smokers than for nonsmokers, but the risk of developing lung cancer for pipe and cigar smokers is less than for cigarette smokers”.

Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9[23] also reported estimates for COPD risk. It concluded that “The data taken as a whole support the conclusion that cigar smoking can cause COPD in smokers who inhale deeply”.

The same Monograph reviews coronary heart disease risk, concluding that “The studies of cigar smoking and coronary events present a pattern of slightly elevated rates among cigar smokers who smoke heavily or inhale deeply”. The Surgeon General’s 1983 report[37] states that “In general, the risk for coronary heart disease mortality of smoking pipes and cigars is substantially lower than the risk of smoking cigarettes. This is generally felt to be due to the tendency of pipe and cigar smokers not to inhale smoke into the lung”.

For risk of stroke, the Surgeon General’s 1983 report[37] cited results from the United States Veterans study[28] (which are included in this review), stating that “Mortality ratios for stroke were near unity for smokers of only cigars or pipes – l.07 and 0.99, respectively.” As noted for lung cancer, there may be differences in stroke risk estimates between studies in the United States and in Europe. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9[23] states “It is difficult to reconcile the results from the European studies and the CPS-I results. The CPS-I primary cigar data are primarily individuals who report that they do not inhale (78 percent), while inhalation information is not provided by the other studies. If inhalation rates are much higher in the European studies, this could explain some of the differences found in the RR of stroke between the two groups of studies.”

Generally, these results reach conclusions quite similar to ours, and suggest that the conclusions we have drawn from our review of the evidence from the United States may not necessarily apply to cigar smoking in Europe.

In conclusion, we find that exclusive cigar smoking is associated with a moderate increase in risk of lung cancer, and a smaller increased risk of COPD and IHD, and that these increases in risk are less than for cigarette smoking.

Many reviews have studied the relationship of smoking to lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease and stroke, but the effects on these diseases of cigar smoking, particularly exclusive cigar smoking, have rarely been considered.

As the United States is a country with a large population and a relatively high percentage of cigar smokers, we felt that insight into the effects of exclusive cigar smoking could usefully be gained from studies conducted there.

To carry out a systematic review of the relationship of exclusive cigar smoking to the four main smoking-related diseases in studies conducted in the United States.

Literature searches were conducted to identify studies in the United States that reported risk of lung cancer, COPD, heart-disease, stroke and/or overall circulatory disease comparing cigar smokers who had never smoked other tobacco products with those who had never smoked any tobacco. For each study identified as providing relevant results, data were recorded on study characteristics and on the appropriate relative risks (RRs) and 95%CIs relating to overall current, former and ever exclusive cigar use, and, for current smokers, by daily cigar consumption. RRs for a given smoking group and disease were combined using fixed-effect and random-effects meta-analyses.

Data were available on lung cancer from 11 studies, on COPD from four studies and on heart disease, stroke and circulatory disease from 10 studies. As RRs tended to be heterogeneous, random-effects estimates are given below. For current smoking overall RR estimates were 2.98 (95%CI: 2.08 to 4.26, based on n = 6 estimates) for lung cancer, 1.44 (1.16 to 1.77, n = 4) for COPD, 1.11 (1.04 to 1.19, n = 6) for ischaemic heart disease, 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13, n = 5) for stroke and 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16, n = 3) for overall circulatory disease. These RRs are much lower than those reported for the United States for exclusive cigarette smokers; 11.68 for lung cancer, 4.56 for COPD and at least 1.70, depending on age, for ischaemic heart disease. Even for heavy cigar smoking, RRs are generally lower than for overall cigarette smoking. RRs for former and for ever smoking were also much lower than for cigarette smoking.

Although our analyses were based on relatively few studies, some conducted some time ago, the results clearly show that exclusive cigar smoking is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer, though much less than is the case for exclusive cigarette smoking. For COPD and ischaemic heart disease the association is weaker, and also less than for cigarette smoking. No previous study has clarified the effects of exclusive cigarette smoking so clearly. Future research could extend results on exclusive cigar smoking to countries other than the United States, and compare risks of cigar smoking with those of using other nicotine products.

While our results show that exclusive cigar smoking is associated with risks of smoking-related diseases that are much lower than those associated with cigarettes smoking, little of the evidence comes from studies conducted in this millenium. Further large prospective studies are needed to collect more up-to-date results, and to clarify how risk varies by type of cigar smoked.

We thank Barbara Forey for assistance with the literature searching and study selection, and comments on drafts of the paper, and also John Fry and John Hamling for assistance with conduct of the meta-analyses. We also thank Yvonne Cooper and Diana Morris for typing the various drafts of the paper.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: OnoT, Ju SQ S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Wynder EL, Mabuchi K, Beattie EJ. The epidemiology of lung cancer. Recent trends. JAMA. 1970;213:2221-2228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Falk RT, Pickle LW, Fontham ET, Greenberg SD, Jacobs HL, Correa P, Fraumeni JF. Epidemiology of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1:339-344. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Sandler DP, Comstock GW, Helsing KJ, Shore DL. Deaths from all causes in non-smokers who lived with smokers. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:163-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chow WH, Schuman LM, McLaughlin JK, Bjelke E, Gridley G, Wacholder S, Chien HT, Blot WJ. A cohort study of tobacco use, diet, occupation, and lung cancer mortality. Cancer Causes Control. 1992;3:247-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Williams RR, Horm JW. Association of cancer sites with tobacco and alcohol consumption and socioeconomic status of patients: interview study from the Third National Cancer Survey. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;58:525-547. [PubMed] |

| 6. | National Cancer Institute. Cigars: health effects and trends. In: Shopland DR, Burns DM, Hoffmann D, Cummings KM, Amacher RH, editors. Smoking and Tobacco Control - Monograph No. 9. Bethesda: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 1998: 232. |

| 7. | Forey B, Hamling J, Lee P, Wald N. International Smoking Statistics. A collection of historical data from 30 economically developed countries. 2nd edition. London and Oxford: Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine and Oxford University Press, 2002: 854. |

| 8. | Forey B, Lee PN. New edition of International Smoking Statistics. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:471-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee PN, Forey BA, Coombs KJ. Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence in the 1900s relating smoking to lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hamling J, Lee P, Weitkunat R, Ambühl M. Facilitating meta-analyses by deriving relative effect and precision estimates for alternative comparisons from a set of estimates presented by exposure level or disease category. Stat Med. 2008;27:954-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fleiss JL, Gross AJ. Meta-analysis in epidemiology, with special reference to studies of the association between exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and lung cancer: a critique. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:127-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46560] [Article Influence: 2116.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Iribarren C, Tekawa IS, Sidney S, Friedman GD. Effect of cigar smoking on the risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer in men. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1773-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Malhotra J, Borron C, Freedman ND, Abnet CC, van den Brandt PA, White E, Milne RL, Giles GG, Boffetta P. Association between Cigar or Pipe Smoking and Cancer Risk in Men: A Pooled Analysis of Five Cohort Studies. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2017;10:704-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rostron BL, Corey CG, Gindi RM. Cigar smoking prevalence and morbidity among US adults, 2000-2015. Prev Med Rep. 2019;14:100821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Inoue-Choi M, Shiels MS, McNeel TS, Graubard BI, Hatsukami D, Freedman ND. Contemporary Associations of Exclusive Cigarette, Cigar, Pipe, and Smokeless Tobacco Use With Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3:pkz036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Christensen CH, Rostron B, Cosgrove C, Altekruse SF, Hartman AM, Gibson JT, Apelberg B, Inoue-Choi M, Freedman ND. Association of Cigarette, Cigar, and Pipe Use With Mortality Risk in the US Population. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:469-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hammond EC, Horn D. Smoking and death rates; report on forty-four months of follow-up of 187,783 men. I. Total mortality. J Am Med Assoc. 1958;166:1159-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hammond EC, Horn D. Smoking and death rates: report on forty-four months of follow-up of 187,783 men. 2. Death rates by cause. J Am Med Assoc. 1958;166:1294-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Boucot KR, Weiss W, Seidman H, Carnahan WJ, Cooper DA. The Philadelphia pulmonary neoplasm research project: basic risk factors of lung cancer in older men. Am J Epidemiol. 1972;95:4-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hammond EC. Smoking in relation to the death rates of one million men and women. In: Haenszel W. Epidemiological approaches to the study of cancer and other chronic diseases. Bethesda: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service National Cancer Institute, 1966: 127-204. |

| 22. | Hammond EC. Smoking habits and air pollution in relation to lung cancer. In: Lee HK. Environmental factors in respiratory diseases. New York: Academic Press Inc, 1972: 177-198. |

| 23. | Shanks TG, Burns D. Disease consequences of cigar smoking - Cigars: Health effects and trends. In: Shopland DR, Burns DM, Hoffmann D, Cummings KM, Amacher RH, editors. Smoking and Tobacco Control - Monograph No. 9. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 1998: 105-158. |

| 24. | Jacobs EJ, Shapiro JA and Thun MJ. Cigar smoking in men and risk of death from tobacco-related cancers. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:S71-S71. |

| 25. | Shapiro JA, Jacobs EJ, Thun MJ. Cigar smoking in men and risk of death from tobacco-related cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:333-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dorn HF. Tobacco consumption and mortality from cancer and other diseases. Public Health Rep. 1959;74:581-593. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Kahn HA. The Dorn study of smoking and mortality among U.S. veterans: report on eight and one-half years of observation. In: Haenszel W. Epidemiological approaches to the study of cancer and other chronic diseases. Bethesda: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service National Cancer Institute, 1966: 1-125. |

| 28. | Rogot E, Murray JL. Smoking and causes of death among U.S. veterans: 16 years of observation. Public Health Rep. 1980;95:213-222. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Levin ML. Etiology of lung cancer: present status. N Y State J Med. 1954;54:769-777. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Sadowsky DA, Gilliam AG, Cornfield J. The statistical association between smoking and carcinoma of the lung. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1953;13:1237-1258. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Higgins IT, Mahan CM, Wynder EL. Lung cancer among cigar and pipe smokers. Prev Med. 1988;17:116-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jacobs EJ, Thun MJ, Apicella LF. Cigar smoking and death from coronary heart disease in a prospective study of US men. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2413-2418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kaufman DW, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L, Shapiro S. Cigar and pipe smoking and myocardial infarction in young men. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;294:1315-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lee PN, Fry JS, Hamling JF, Sponsiello-Wang Z, Baker G, Weitkunat R. Estimating the effect of differing assumptions on the population health impact of introducing a Reduced Risk Tobacco Product in the USA. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;88:192-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wynder EL, Mabuchi K. Lung cancer among cigar and pipe smokers. Prev Med. 1972;1:529-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | US Surgeon General. Smoking and health - A report of the Surgeon General -DHEW Publication No. (PHS) 79-50066. Vol Rockville: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service, 1979: 1194. |

| 37. | US Surgeon General. The health consequences of smoking - Cardiovascular disease - A report of the Surgeon General - DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 84-50204. Vol Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 1983: 384. |