Published online Jun 30, 2019. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v7.i6.269

Peer-review started: March 20, 2019

First decision: May 16, 2019

Revised: June 7, 2019

Accepted: June 16, 2019

Article in press: June 17, 2019

Published online: June 30, 2019

Processing time: 103 Days and 14 Hours

Multivisceral resections (MVR) are often necessary to reach clear resections margins but are associated with relevant morbidity and mortality. Factors associated with favorable oncologic outcomes and elevated morbidity rates are not clearly defined.

To systematically review the literature on oncologic long-term outcomes and morbidity and mortality in cancer surgery a systematic review of the literature was performed.

PubMed was searched for relevant articles (published from 2000 to 2018). Retrieved abstracts were independently screened for relevance and data were extracted from selected studies by two researchers.

Included were 37 studies with 3112 patients receiving MVR for colorectal cancer (1095 for colon cancer, 1357 for rectal cancer, and in 660 patients origin was not specified). The most common resected organs were the small intestine, bladder and reproductive organs. Median postoperative morbidity rate was 37.9% (range: 7% to 76.6%) and median postoperative mortality rate was 1.3% (range: 0% to 10%). The median conversion rate for laparoscopic MVR was 7.9% (range: 4.5% to 33%). The median blood loss was lower after laparoscopic MVR compared to the open approach (60 mL vs 638 mL). Lymph-node harvest after laparoscopic MVR was comparable. Report on survival rates was heterogeneous, but the 5-year overall-survival rate ranged from 36.7% to 90%, being worst in recurrent rectal cancer patients with a median 5-year overall survival of 23%. R0 -resection, primary disease setting and no lymph-node or lymphovascular involvement were the strongest predictors for long-term survival. The presence of true malignant adhesions was not exclusively associated with poorer prognosis.

Included were 16 studies with 1.600 patients receiving MVR for gastric cancer. The rate of morbidity ranged from 11.8% to 59.8%, and the main postoperative complications were pancreatic fistulas and pancreatitis, anastomotic leakage, cardiopulmonary events and post-operative bleedings. Total mortality was between 0% and 13.6% with an R0 -resection achieved in 38.4% to 100% of patients. Patients after R0 resection had 5-year overall survival rates of 24.1% to 37.8%.

MVR provides, in a selected subset of patients, the possibility for good long-term results with acceptable morbidity rates. Unlikelihood of achieving R0 -status, lymphovascular- and lymph -node involvement, recurrent disease setting and the presence of metastatic disease should be regarded as relative contraindications for MVR.

Core tip: Multivisceral resections constitute a huge challenge for an interdisciplinary team. Proper patient selection, combined perioperative systemic treatment and en-bloc resection of adherent organs can provide acceptable morbidity-, mortality- and long-term survival rates.

- Citation: Nadiradze G, Yurttas C, Königsrainer A, Horvath P. Significance of multivisceral resections in oncologic surgery: A systematic review of the literature. World J Meta-Anal 2019; 7(6): 269-289

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v7/i6/269.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v7.i6.269

Patients with locally advanced primary and recurrent cancers constitute a challenge for the interdisciplinary treatment team because the only chance for cure and prolonged survival is complete resection of the tumor with clear margins. Invasion of adjacent organs occurs in 10%-20% of patients suffering from colorectal cancer and gastric cancer. The prerequisite for long- and short-term results is completeness of surgical resection. This aggressive surgical concept is accompanied by pre- and postoperative systemic treatment schedules, consisting of chemotherapy, radio-therapy and chemoradiotherapy. Due to the lack of sufficient and reliable pre-operative data the decision in favor of multivisceral resections (MVR) is often made intraoperatively. MVR is defined as the en-bloc resection of the tumor and the adjacent organs including reproductive organs and organs of the urinary tract. MVR should therefore always be taken into account if macroscopic complete resection is achievable. Adherence of the primary or recurrent tumor to adjacent structures does not necessarily predict true malignant invasion. Winter et al[1] stated that up to two-third of cases are postoperatively classified as inflammatory adhesions rather than true malignant invasion. Furthermore, lysis of adhesions or separation of the adjacent organ from the tumor dramatically increases the risk of recurrence and should be avoided. The significance of palliative MVR for patients with obstruction, fistula and pain is not clearly defined but the data presented in this review suggest that non-curative MVR does not improve patient outcome. Leijssen et al[2] showed that patients with a T4 -tumor not undergoing MVR had a poorer outcome regarding overall-, disease-free-, and cancer-specific survival. The indication in favor of MVR for patients with metastatic disease is also common in the current literature but the true benefit of MVR for stage IV disease is unclear.

This review aims to systematically evaluate the current literature on outcomes following MVR for colorectal and gastric cancer and for patients undergoing MVR and HIPEC for peritoneal metastasis of gastrointestinal, especially colorectal, origin.

A systematic review was conducted with reference to the PRISMA statement and the current methodological literature[3,4]. Electronic medical literature databases were screened for appropriate publications from 2000 to 2018. Databases were searched using the following terms: “multivisceral” AND “colon cancer”, “multivisceral” AND “rectal cancer”, “multivisceral” AND “gastric cancer”, “multivisceral AND “cytoreductive surgery”, and “multivisceral” AND “hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy”. Comments and case reports were excluded. Furthermore, pub-lications that did not report performance of MVR, morbidity and mortality rates, oncologic outcome and publications that included unspecified cancer types were also not included in this systematic review.

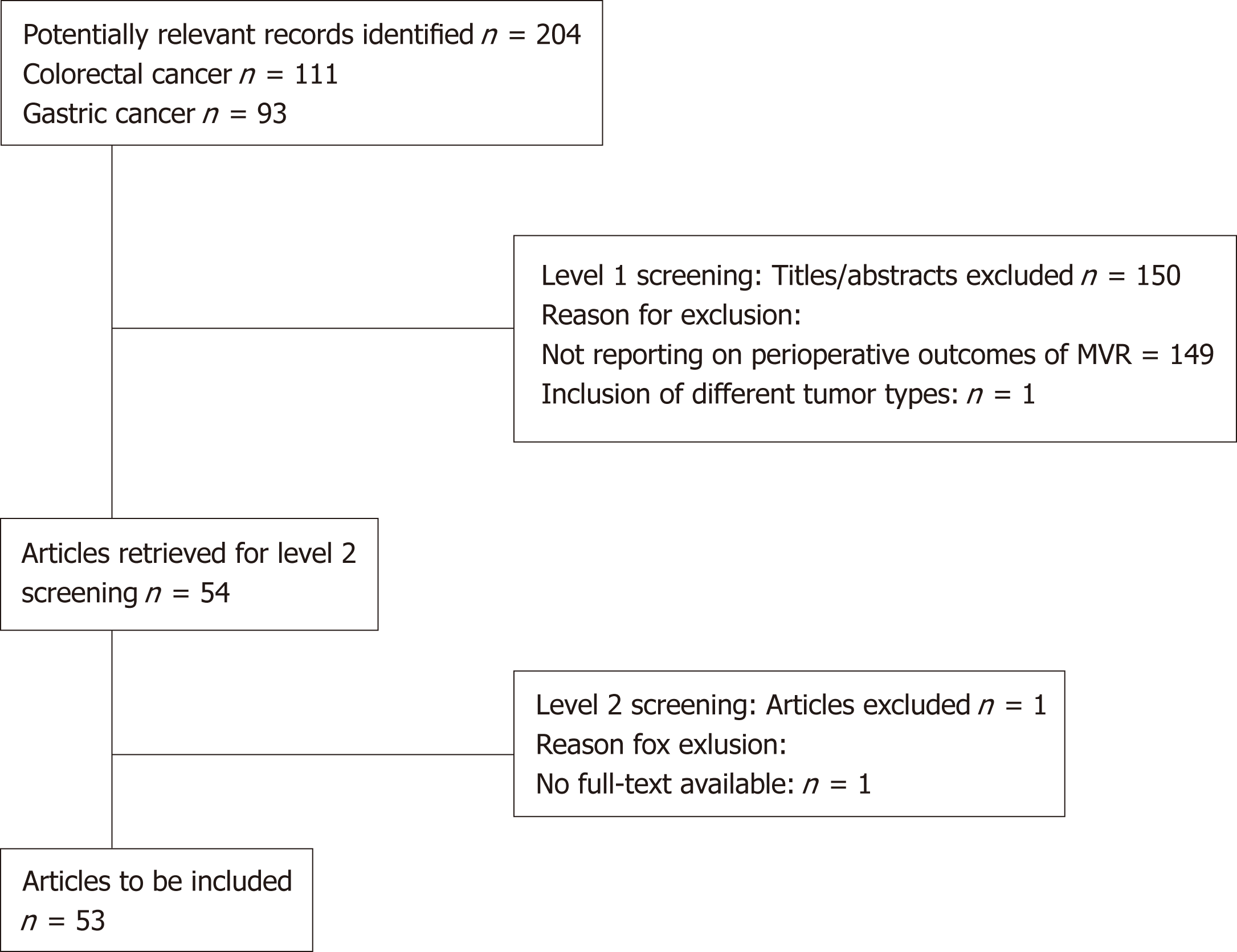

For the search terms “multivisceral” AND “colon cancer” and “multivisceral” AND “rectal cancer” 211 records were provided. After the abstracts were screened (level 1 screening) independently by two reviewers 165 publications excluded (Figure 1).

For the search terms “multivisceral” AND “gastric cancer” 93 records were provided. After the abstracts were screened (level 1 screening) independently by two reviewers 71 publications excluded.

After level 2 screening, 37 publications for “Multivisceral resection for colon cancer and rectal cancer”, 16 publications for “Multivisceral resection for gastric cancer and 3 publications for “Multivisceral resections with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemo-therapy” were included.

MVR were defined as resection of more than two organs.

MVR for colon cancer and rectal cancer (n = 37).

After full-text screening 37 studies were selected that met the inclusion criteria. Of these 37 included studies, 36 were retrospective.

In total 3112 patients underwent MVR for colon and rectal cancer (1095 for colon cancer, 1357 for rectal cancer and in 660 patient’s origin of primary tumor was not specified (Table 1). Of the 36 studies ten included patients with recurrent colon and rectal cancer. The remainder dealt only with primary colon and rectal cancer. Included studies were published after 1999 to the present time and all but one was retrospective. In total five publications presented patient- and treatment-related data after minimally-invasive MVR. The decision for or against suspected MVR, according to preoperative imaging modalities like CT, MRI, EUS and PET-CT, was made intraoperatively. Every verified adhesion of the primary tumor to adjacent structures was classified as a cT4b -situation. All but seven publications did not report the true pT4b -rate. There were 17 studies that included patient with Stage IV disease. Another seven studies did not specify whether or not patients with metastatic disease were included.

| Study/Yr | n | Disease | Site |

| Cukier et al[24], 2012 | 33 | Primary | Colon |

| Hallet et al[20], 2014 | 15 | Recurrent | Colon |

| Kumamoto et al[15], 2017 | 118 | Primary | Colon |

| Leijssen et al[2], 2018 | 103 | Primary | Colon |

| López-Cano et al[49], 2010 | 113 | Primary | Colon |

| Rosander et al[7], 2018 | 121 | Primary | Colon |

| Takahashi et al[12], 2017 | 84 | Primary | Colon |

| Tei et al[23], 2018 | 29 | Primary | Colon |

| Chen et al[6], 2011 | 287; Colon (152); Rectum (135) | Primary recurrent | Colorectal |

| Eveno et al[58], 2014 | 152; Colon (81); Rectum (71) | Primary | Colorectal |

| Fujisawa et al[29], 2002 | 35; Colon (19); Rectum (17) | Primary recurrent | Colorectal |

| Hoffmann et al[21], 2012 | 78; Colon (52); Rectum (26) | Primary | Colorectal |

| Gezen et al[18], 2012 | 90; Colon (43); Rectum (47) | Primary | Colorectal |

| Kim et al[17], 2012 | 54; Colon (32); Rectum (22) | Primary | Colorectal |

| Laurence et al[56], 2017 | 660; Colon/Rectum not specified | Primary | Colorectal |

| Lehnert et al[8], 2002 | 201; Colon (139); Rectum (62) | Primary | Colorectal |

| Li et al[16], 2011 | 72; Colon (28); Rectum (44) | Primary | Colorectal |

| Park et al[53], 2011 | 54; Colon (23); Rectum (31) | Primary | Colorectal |

| Rizzuto et al[57], 2016 | 22; Colon (16); Rectum (6) | Primary | Colorectal |

| Winter et al[1], 2007 | 63; Colon (46); Rectum (17) | Primary | Colorectal |

| Bannura et al[55], 2006 | 30 | Primary | Rectal |

| Crawshaw et al[25], 2015 | 61 | Primary recurrent | Rectal |

| Derici et al[48], 2008 | 57 | Primary | Rectal |

| Dinaux et al[50], 2018 | 29 | Primary | Rectal |

| Dosokey et al[30], 2017 | 34 | Primary | Rectal |

| Gannon et al[28], 2007 | 72 | Primary recurrent | Rectal |

| Harris et al[19], 2011 | 42 | Primary | Rectal |

| Ishiguro et al[54], 2009 | 93 | Primary | Rectal |

| Mañas et al[13], 2014 | 30 | Primary | Rectal |

| Nielsen et al[9], 2012 | 90 | Primary recurrent | Rectal |

| Pellino et al[14], 2018 | 82 | Primary | Rectal |

| Rottoli et al[10], 2017 | 46 | Primary recurrent | Rectal |

| Sanfilippo et al[51], 2001 | 32 | Primary | Rectal |

| Shin et al[22], 2016 | 22 | Primary | Rectal |

| Smith et al[47], 2012 | 124 | Primary | Rectal |

| Vermaas et al[11], 2007 | 35 | Primary recurrent | Rectal |

In the event of adhesion of adjacent structures to the primary tumor, these adhesions should definitely not be separated intraoperatively. For the surgeon it is not possible to distinguish between inflammatory and malignant adhesions. Hunter et al[5] showed that patients with adherent colon cancer and lysis of adhesion, had a local recurrence rate of 69% and a 5-year overall survival rate of only 23%. Of the included studies, 30 publications report the histopathologically confirmed malignant invasion rate. The true pT4b -rate varied from 23% to 77%. Three publications performed multivariate analysis in order to determine whether true malignant invasion into adjacent structures is of predictive value for overall- and progression-free survival[6-8]. Rosander et al[7] and Lehnert et al[8] did not find malignant invasion to be a predictive factor in multivariate analysis. Rosander et al[7] found female sex, adjuvant che-motherapy, low tumor stage and R0-resection to be associated with better overall survival. On the other hand, Lehnert et al[8] found intraoperative blood loss, age older than 64 years and UICC stage to be predictive. Contrary to the aforementioned results Chen et al[6] found adhesion pattern (inflammatory vs malignant) to be highly sig-nificantly associated with reduced overall survival for both, colon and rectal cancer patients.

Concerning resection status, 27 studies report R0 rates, ranging from 65% to 100%. In the vast majority of publications R0 vs R1 -status was of significant prognostic impact (Table 2). Data show a trend towards decreased R0 -rates in patients un-dergoing MVR for recurrent cancers, especially rectal cancer. Nielsen et al[9], Rottoli et al[10] and Vermaas et al[11] reported resection status in primary and recurrent rectal cancers and showed decreased R0 -rates for recurrent rectal cancer without being sta-tistically significant (66% vs 38%; 71% vs 56% and 82% vs 58%).

| Study | Resection margin (R0 vs R1) | Local and distant recurrence | Most common resected organs | Lymph node involvement | Age | Blood loss(mL) | Pre-operative (Chemo)-radiation | Complications (AI;SSI;IAA) (Re-OP) | Prognostic factors/con-clusions |

| Cukier et al[24] | R0: 100% | LR: 6%; DR: 18% | Small bowel (56%); Bladder/ Ureter (54%) | N0: 79% N1: 21% | 64 | NR | RCTX:100% | 6%; 18%; NR (9%) | No statistical difference in terms of disease-free survival when analyzing subgroups stratified by nodal-status ypN0 vs ypN1: (P = 0.29) |

| Hallet et al[20] | R0: 87% | LR: 13%; DR: 13% | Colon (87%) Small bowel (47%) Bladder (40%) | N0: 70% N1: 30% | 60.2 | 1500 | RCTX:100% | NR | Neoadjuvant RCTX for recurrent colon cancer is feasible; no addition of toxicity (radiation plus MVR) |

| Kumamoto et al[15] | R0: 95% | LR: R0: 1.8% R1: 66.7%; DR: NR | Small bowel (14%) Bladder (12%) Colorectum (11%) | N0: 62% N1: 28% N2: 10% | 64 | 48 | CTX: 4.4% | (0.8%; 2.5%; 0.8%) (0%) | R1-resection and N+ status predictors of poor prognosis Laparoscopic approach: Feasible, low conversion, low R1-rate |

| Leijssen et al[2] | R0: 89% | LR: 14.5%; DR: 10.9% | Small intestine (31%); Reproductive organs (9%); Bladder (7%) | NR | 69 | NR | NR | (1.8%; 3.6%; NR) (2%) | Patients with T4-cancer not undergoing MVR had a significantly poorer outcome regarding overall-, disease-free and cancer-specific survival |

| López-Cano et al[49] | R0: 85% | LR: 23%; DR: 19% | Small intestine (42%) Oophorectomy (28%) Bladder (19%) | N0: 35% N1: 32% N2: 34% | 71 | NR | 0% | (NR; 10%; NR) (8%) | Poorly differentiated tumors and stage IV were associated with a poor survival; significant predictors of disease progression: Venous invasion (RR 2.34) and four or more positive lymph nodes (RR 3.99) |

| Rosander et al[7] | R0: 93% | LR: R0: 7% R1: 33% DR: 14% | Bowel (45%) Ovaries (24%) Bladder (partial/total): 22%/19% Uterus/Vagina (17%) | N0: 71% N1: 19% N2: 10% | 67 | NR | CTX: 27% RT: 1% RCTX: 5% | (8%; 7%; 7%) (14%) | Female sex, low tumor stage, and adjuvant CTX, and N - but not tumor infiltration per se, were independently associated with better overall survival |

| Takahashi et al[12] | R0: 96% | LR: 2% | Bowel (38%); Uterus/Ovaries (5%); Bladder (11%) | NR | 68.5- 71.5 | Lap. completion: 50; Conversion: 366; Lap overall: 57.5; open: 321 | CTX: open: 25% lap: 6% | (4%; NR; NR) (NR) | Overall- and disease-free survival (multivariate) was shorter in the males; operative approach did not affect overall- and disease-free survival |

| Tei et al[23] | R0: 93%-100% | LR: NR; DR: 24% | Small intestine (38%); Bladder (17%); Ovaries (14%) | N0: 48% N1: 24% N2: 28% | 70 | 60-220 | NR | (3%; 17%; 10%) (3%) | S-MVR and M-MVR do not differ significantly in terms of blood loss, operative time and number of harvested lymph nodes. No difference in occurrence of complications |

| Chen et al[6] | NR | NR | Colon cancer: small bowel (40%); Rectal cancer: Bladder (36%) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Multivariate analysis showed that adhesion pattern was independently associated with overall survival among both colon (P = 0.00001) and rectal (P = 0.0002) cancer patients |

| Eveno et al[58] | R0: 90% | NR | Vagina (25%); Small bowel (23%); Bladder (20%); Ovaries/Uter-us (each 19%) | N0: 55% N1: 25% N2: 19% | 63 | NR | RT: 8%; CT: 2%; RCTX: 27% | (3%, 4%; NR) (9%) | Patients with resection of multiple organs had a better survival rate than patients with single organ resection (P = 0.0469) |

| Fujisawa et al[29] | NR | NR | Bladder (partial/total): 54%/34% | NR | 59 | NR | 0% | NR | Complication rate was higher in pat; undergoing cystectomy vs partial cystectomy (58.3% vs 10.5%) |

| Hoffmann et al[21] | R0: 95% | LR: 2% | 53%: 1 add. Organ 27%: 2 add; organs | NR | 69 | NR | RCTX (rectal): 35% | (9%; 9%; NR) (19%) | No significant differences in overall survial: Colon vs rectal cancer (P = 0839); lap vs open (P = 0.610); emergency vs planned (P = 0.674), pN0 vs pN1 (P = 0.658) |

| Gezen et al[18] | R0: 91% | NR | Ovaries: 27%; Bladder: 26%; Small bowel: 21%; Uterus: 19% | NR | 59 | 450 (non-MVR: 250) | NR | (2%; 3%; 1%) (2%) | MVR do not alter the rates of sphincter-saving procedures, morbidity and 30-d mortality |

| Kim et al[17] | R0: 71% | LR: 7.7% (lap) and 27.3% (open) P = 0.144) DR: 15.4% (lap) vs 45.5% (open) P = 0.091) | Small bowel: 10%; Bladder: 10%; Seminal vesicle: 13%; Prostate: 6% | NR | 68 | lap: 269; open: 638 | RCTX: 50% of rectal cancer patients | (12%; 8%; NR) (NR) | No adverse long-term oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic MVR were observed |

| Laurence et al[56] | NR | NR | NR | NR | 64 | NR | RT: 62% | NR | Female gender, tumor grade 2, MVR were significant protective factors of mortality |

| Lehnert et al[8] | R0: 65% R1: 9% R2: 26% | LR: 7% DR: 13% Both: 4% | Small bowel: 29%; Bladder: 24%; Uterus: 13% | NR | 64 | < 1000 mL: 37%; 1000-2000 mL: 13%; > 2000 mL: 10% | RT/CT/RCTX: 40% of R0 resected patients | (5%; 9%; 1%) | Intraoperative blood loss, age older than 64 and UICC stage but not histologic tumor infiltration vs inflammation were prognostic factors |

| Li et al[16] | NR | LR at 5 years: 15% DR: 14% | Bladder (partial/total): 56%/19% | NR | 67 | Partial cystectomy: 0; Urologic reconstruction: 1700 | 0% | (19%; 25; 6%) (4%) | Negative prognostic factors: Age older than 70 years; receiving palliative resection and not involvement of the bladder dome |

| Park et al[53] | NR | NR | Small bowel: 24%; Ovary: 17%; Bladder 14% | NR | 64 | NR | NR | (6%; 11%; 9%) (NR) | MVR was associated with a two times higher complications rate compared to standard resections |

| Rizzuto et al[57] | R0: 91% | NR | Small bowel: 36%; Bladder: 27%; Vagina/Uterus/Ovaries: Each 22% | N0: 50% N+: 50% | 62 | NR | RCTX: 28% | (11%; 14%; 5%) (NR) | Patients with rectal cancer and occlusive disease had worse prognosis |

| Winter et al[1] | R0: 89% | LR: 14% | Bladder (partial): 84% | N0: 65% N1: 35% | 63 | NR | RCTX: 37% | (3%; NR; NR) (NR) | Bladder reconstruction is achievable in most patients; margin- and node-negative patients benefit the most |

| Banamura et al[56] | NR | LR: 13%; DR. 23%: Both: 20% | APR: 30%; PPE: 70% | NR | 57 | NR | RCTX: 20% | (3%; 27%; NR) (NR) | PPE showed prolonged operative time, higher postoperative complications, a trend towards a poor prognosis in recurrence and survival |

| Crawshaw et al[25] | R0: 87% | LR: 16% | Bladder: 49%; Vagina: 38%; Prostate: 31%; Uterus: 31%; Ovaries: 20%; Small bowel: 10% | NR | 62 | 800 | RCTX: 90% | (NR; 7%; 12%) (NR) | Sphincter perseveration did not affect oncologic outcomes |

| Derici et al[48] | R0: 75% | LR: 18% | Adnexa: 47%; Uterus: 32%; Bladder: 30% | NR | 60 | NR | RCTX: 51% | (7%; 19%; NR) (NR) | Lymph node status pN0 (P = 0.007) and R0 resection (P = 0.005) were independently significant factors in the multivariate analysis for overall survival |

| Dinaux et al[50] | R0: 100% | LR. 3%; DR: 21% | Bladder: 28%; Prostate: 21%; Ovaries: 20%; Uterus: 20% | NR | 55 | NR | CTX. 100%; RCTX: 97% | (3%; 14%; 3%) (NR) | Chance of overall mortality significantly increased for patients; who underwent MVR, for administra-tion of adjuvant CTX, for Pn+ and ypN+ status |

| Dosokey et al[30] | NR | LR. 3% DR: 11% | Vagina: 50%; Prostate: 30%; Bladder: 33% | NR | 66 | 549 | CTX: 97% RT: 92% | (16%; NR; NR) (NR) | Patients with APR only had a longer 5 yr overall survival and a longer disease-free survival compared to patients undergoing MVR |

| Gannon et al[28] | R0: 90% | Primary: LR: 9%, LR + DR: 13%, DR: 22%; Recurrent: LR: 4%, LR + DR: 48%, DR:15% | TPE: 47% SLE: 47% PPE: 33% | NR | 52 | NR | RCTX: 85% | (NR; 4%; 11%) (4%) | A significant difference in 5-yr disease-free survival was found between primary and recurrent tumors (52% vs 13%, P < 0.01) |

| Harris et al[19] | R0: 93% | LR: 7% | Bladder+ Prostate: 55% Uterus: 24% | N0: 52% N1: 29% N2: 17% N3: 2% | 62 | NR | RCTX: 74% | (5%; 5%; 21%) (20%) | Association with worse overall survival in multivariate analysis: Metastatic disease, pT4N1 stage, vascular invasion |

| Ishiguro et al[54] | R0: 98% | LR: 9% DR: 25% | Uterus+ Bladder+ Rectum: 89% | N0: 57% N+: 43% | 55 | NR | RCTX: 14% | (4%; 23%; 8%) (9%) | Patients with positive lateral pelvic lymph node had a higher probability to recur and a decreased 5-yr over all survival |

| Mañas et al[13] | R0: 73% | LR: 37% DR: 35% | Uterus/Ovaries (each): 53%; Vagina; 27%; Seminal vesicle: 23% | N0: 40% N1: 27% N2: 34% | 68 | NR | RCTX: 20% | (13%; 53%; 10%) (NR) | Multivariate analysis showed that nodal involvement was independent predictor of poor survival (> 4 pos; nodes RR: 9.06 (P = 0.006) |

| Nielsen et al[9] | Primary:R0: 66% Recurrent: R0: 38% | NR | TPE with sacrectomy: 22% | NR | 63 | NR | RT: 65% | (4%; 20%; 7%) (NR) | There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between primary and recurrent disease when comparing R0 resections |

| Pellino et al[14] | R0: 77% | LR: 16% DR: 22% | Not clearly specified | N0: 13% N1: 29% N2: 43% | 62 | NR | RT: 54% | (NR; 37%; 10%) (10%) | Perioperative complications were independent predictors of shorter survival (HR 3.53) |

| Rottoli et al[10] | Primary: R0 71%, Recurrent: R0: 56% | Primary: LR: 18% DR: 29% Both: 7%; Recurrent: LR: 22% DR: 33% Both: 17% | Sacrectomy: Primary: 18% Recurrent: 22%) | N0: 41% N1: 15% N2: 37% | 57 | Primary: 600 Recurrent: 750 | 65% (not specified) | NR | The long-term disease-free survival of patients undergoing pelvic exenteration is significantly worse when the procedure is performed for recurrent rectal cancer, regardless of the tumor involvement of the resection margins |

| Sanfilippo et al[51] | NR | LR: 20% DR: 44% | Vagina: 66%; Bladder/Prostate: 14%; Bladder/Vagina: 6%; Vagi-na/Uterus/O-varies: 6% | N0: 72% N1: 9% N2: 9% | 55 | NR | RCTX: 100% | (NR; 19%; 6%) (9%) | No significant association with pelvic control rate and age, sex, cN-stage, tumor distance from the anal verge, clinical tumor length, tumor circumference, tumor mobility, obstruction, grade, neoadjuvant CTX, and MVR |

| Shin et al[22] | R0: 100% | LR: 4% | Prostate: 36%; Vagina: 23%; Small bowel: 14%; Bladder wall: 14% | N0: 41% N1: 46% N2: 14% | 54 | 225 | RCTX: 82% | (NR; 17%; 17%) (13%) | Robotic MVR including resection of lateral pelvic lymph nodes is feasible with acceptable morbidity and no conversion |

| Smith et al[47] | R0: 85% | LR: 19% | Vagina: 52%; Uterus: 23%; Bladder: 11% | N0: 60% N+: 40% | 63 | NR | RCTX: 73% RT: 2% | (6%; 19%; 6%) (at least 1%) | 5-yr overall survival in stage I-III: Tumor category (T3-4 vs T0-2: HR 2.80), Node category (N1-2 vs N0: HR 1.75), Involved resection margin: HR = 2.19), lymphovascu-lar invasion (L0 vs L1: HR 1.56) |

| Vermaas et al[11] | Primary:R0: 82%; Recurrent: R0: 58% | LR at 5-yr: Primary: 12%; Recurrent: 40% | TPE: 83% TPE an sacral bone: 11%; TPE with coccygeal bone: 6% | N0: 37% N1: 6% N2: 6% | 58 | NR | RT: 97% | (NR; 26%; NR) (9%) | Patients with recurrent rectal cancers have a higher rate of complications, a high distant metastasis rate and a poor overall survival |

There was heterogeneity in reporting total complication rate, degree of complications and specification of different complications, so that the focus was set on com-plications, which were reported in the vast majority of publications. The post-operative morbidity rates ranged from 7%[12] to 76.6%[13]. Only one study reported that the occurrence of perioperative complications was an independent predictor of shorter overall survival (HR 3.53)[14].

Anastomotic insufficiency: Twelve studies did not report occurrence of anastomotic insufficiency (AI). The remainder reported AI-rates ranging from 0.8%[15] to 19%[16]. There was no structured report on management of AI in the studies included.

Surgical site infection: Surgical site infections (SSI) were one of the most common complications ranging from 2.5%[15] to 53%[13]. The differentiation into superficial and deep SSI was inconsistently used in the studies included. Kumamoto et al[15] reported the lowest rate of SSI including 118 patients undergoing minimally-invasive MVR. The other studies, looking at minimal-invasive MVR, reported SSI -rates ranging from 12%-17%. The study by Kim et al[17] found no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of SSI between the open and the minimally-invasive group.

Intraabdominal abscess: Intraabdominal abscess (IAA) formation was not reported in 17 studies. The remainder reported IAA rates ranging from 1%[18] to 21%[19]. Documentation of IAA management was again inconsistently reported in the in-cluded studies.

Re-operation: The rate of necessary surgical re-intervention was again not reported in 17 studies. In the remaining studies the re-operation rate ranged from 0%[14] to 20%[19].

Mortality: In total 15 studies reported mortality rates of 0% and the median mortality rate was 1.3%. The highest reported perioperative mortality rate, namely 10% was reported in the study by Manas et al[13].

Table 3 shows overall (OS)- and disease-free survival (DFS) rates and depicts factors associated with decreased OS and DFS after MVR for rectal and colon cancers. 5-year OS rate ranged from 36.7%[13] to 90%[20], but the proportion of included patients with metastatic disease differed between those two studies (20% vs 0%).

| Study | Follow-up (mo) | Morbidity (%) | Mortality (%) | Survival1 | Stage IV disease (%) | True pT4b (%) |

| Cukier et al[24] | 36 | 36 | 0 | 3-yr OS: 85.9%; 3-yr DFS: 73.7% | 0 | 67 |

| Hallet et al[20] | 54 | 33.3 | 0 | 90%; 5-yr DFS: 63.5% | 0 | 50 |

| Kumamoto et al[15] | 32 | 17.8 | 0.8 | 87% | 12 | 45 |

| Leijssen et al[2] | 48.5 | 25 | 0 | 5-yr OS (pT3): 63%; 5-yr OS (pT4): 70% | 0 | 24 |

| López-Cano et al[49] | 74.9 | 47.8 | 7.1 | 48%; 5-yr DFS: 46.3 mo | 20 | 65 |

| Rosander et al[7] | 28 | 37% (≥ Grade III) | 5 | 60.8% for the infiltration group; 86.9% for the inflammation group | 0 | 63 |

| Takahashi et al[12] | 48.4 | LAP: 7 OPEN: 36 | 0 | 3-ys OS (open): 79.8%; (lap): 92.8% | 25 | 50 |

| Tei et al[23] | 34 | 37.9 | 0 | 3-yr OS Stage II-III (S-MVR/M-MVR): 81.8%/80.0% 3-yr DFS Stage II-III (S-MVR/M-MVR: 58.3%/70.0% | 28 | 34 |

| Chen et al[6] | NR | 11.5 | NR | 59% (Colon/inflammation) 39% (Colon/invasion) 63% (Rectum/inflammation); 42% (Rectum/invasion) | 54 | 55 |

| Eveno et al[58] | 48 | 12 | 1.3 | 77%; 3-yr OS (without stage IV disease): 89%; 5-yr DFS: 58% | 13 | 65 |

| Fujisawa et al[29] | 42 (mean) | NR | NR | 3-yr OS (colon/bladder sparing): 90%; (colon/nonsparing): 67%; 3 yr OS (rectal/bladder sparing): 50%; (rectal/nonsparing): 67% | NR | NR |

| Hoffmann et al[21] | NR | 34.6 | 7.7 | 55% (if curative) | 49 | 63 |

| Gezen et al[18] | 25 (mean) | 24.4 | 4.4 | 69.4% | 12 | 34 |

| Kim et al[17] | 35/40 (mean) | LAP: 21 OPEN: 44 | 0 | LAP: 60.5%; OPEN 48% | 33 | 44 |

| Laurence et al[56] | NR | NR | NR | 52.7% | 3 | NR |

| Lehnert et al[8] | 71 | 33 | 7.5 | 51% | 5 | 50 |

| Li et al[16] | 64.3 | 61 | 5.6 | 50%; 59%: if curative | 21 | 47 |

| Park et al[53] | NR | 35.2 | 3.1 | 58% | 0 | 44 |

| Rizzuto et al[57] | NR | 55 | 0 | 3-yr OS (non-occlusive): 58.4%; (occlusive): 33.3% | 0 | 77 |

| Winter et al[1] | 84 | 18 | 1.5 | 57%; 61% (R0); 17% (R1) 77% (R0, N0); 28% (R0, N+) | NR | 54 |

| Banmura et al[56] | 32 | 50 | 0 | Local recurrence rate: 30% | 33 | 63 |

| Crawshaw et al[25] | 27.8 | 57.4 | 0 | 49.2%; 5-yr DFS: 45.3% | 0 | 39 |

| Derici et al[48] | 40.4 (mean) | 38.6 | 3.5 | 49%; 3-yr OS: 81.6% | 0 | 58 |

| Dinaux et al[50] | 38.2 | 72.4 | 0 | OS: 45 mo | 0 | 24 |

| Dosokey et al[30] | 32 (mean) | 39 | 0 | 67%; 5-yr DFS: 79% | 0 | NR |

| Gannon et al[28] | 40 | 43 | 0 | 48%; Primary: 65% Recurrent: 22%; 5-yr DFS. 38%; Primary: 52% Recurrent: 13% | NR | NR |

| Harris et al[19] | 30 | 50 | 0 | 5-yr OS (R0): 48%; R1/R2: 33% | 14 | 52 |

| Ishiguro et al[54] | 40 | 39.8 | 2.2 | 52%; 5-yr DFS: 46% | NR | 49 |

| Mañas et al[13] | 28.8 | 76.6 | 10 | 36.7% | 20 | 67 |

| Nielsen et al[9] | 12 | 51 | 2.2 | 5-yr OS (primary): 46%; (recurrent):17% | 0 | NR |

| Pellino et al[14] | NR | 54.9 | 2.4 | 67% | NR | 70 |

| Rottoli et al[10] | 32.5/56.6 | 33 Primary: 32% Recurrent: 33% | 4 | 5-yr DFS (primary): 46% (recurrent): 24% | NR | NR |

| Sanfilippo et al[51] | NR | 25 | NR | 4-yr OS: 69% | 0 | 44 |

| Shin et al[22] | 30 | 41.7 | 0 | 80% | 27 | 23 |

| Smith et al[47] | NR | 47.6 | 0.8 | 53.3%; M0: 59% | 20 | 44 |

| Vermaas et al[11] | 28 (mean) | 69; Primary: 61; Recurrent: 83 | 3 | 52% (primary); 3-yr OS (recurrent): 32% | NR | 43 |

Local and distant recurrences: The local control rate expressed by the local recurrence rate were reported in 27 publications and ranged from 1.8% to 66.7%[15]. The aforementioned study and Rosander et al[7] showed higher rates of local recurrences after R1 -resection. Distant recurrence rates varied from 10.9%[2] to 45.5%[17]. Patients with metastatic disease, receiving MVR, were also included in the vast majority of publications and the rate of patients with Stage-IV disease varied from 0% to 49%[21].

Laparoscopic vs open surgery: Five publications focused on the perioperative und long-term results of minimally-invasive (laparoscopic and/or robotic) MVR (Table 4). Completeness of surgical resection was not impaired by minimally-invasive MVR and the included studies showed no reduction in lymph -node harvest as compared to open surgery. The conversion rate to open surgery varied from 4.5%[22] to 33%[23]. The most common reasons for conversion were involvement of the small intestine, intraperitoneal adhesions and the need for urologic reconstructive procedures. The minimally-invasive approach offered a reduced length of stay, significantly reduced blood loss but prolonged operative time.

| Study | Resection margin (R0 vs R1) | Lymph-node harvest (n) | Conversion rate | Reason for conversion | Blood loss (mL) | Operative time (min) | LOS (d) |

| Kumamoto et al[15] | R0: 95% | 26 | 6.8% | Excessive tumor fixation (n = 4); Suspicion of invasion to the duodenum (n = 2); Intraperitoneal adhesion (n = 2) | 49 | 254 | 11 |

| Takahashi et al[12] | R0: 96% | 34 Open: 33 | 12% | The conversion rate was highest in cases involving the urinary tract (40%) | 50; Open: 321 | 279; Open: 255 | 14; Open: 22.5 |

| Tei et al[23] | R0: S-MVR: 100%; M-MVR: 93% | S-MVR: 30; M-MVR: 25 | S-MVR M-MVR: 14%; M-MVR Open: 33% | Small intestine involvement | S-MVR: 60; M-MVR: 220 | S-MVR: 222; M-MVR: 255 | S-MVR: 11; M-MVR: 18 |

| Kim et al[17] | R0: 71% | 34; Open: 40 | 7.9% | NR | 268; Open: 637 | 330; Open: 257 | 21.9; Open: 21 |

| Shin et al[22] | R0: 100% | 20 | 4.5% | Unable to tolerate Trendelenburg position and intraperitoneal adhesions | 225 | 421 | 4.5 |

The number of patients receiving any kind of preoperative therapy, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy and combined chemoradiotherapy, was mentioned in 31 studies. Preoperative chemotherapy was received by 129 (4%) patients, 591 (19%) patients underwent preoperative radiotherapy and 423 (14%) patients were given preoperative combined chemoradiotherapy. Two studies reported on applications of chemoradiotherapy in primary and recurrent colon cancers[20,24]. Cukier et al[24] reported that perioperative complication rates were not negatively impacted by chemoradiotherapy. The same results were obtained by Hallet et al[20] who stated that the addition of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy prior to MVR for recurrent adherent colon cancer did not elevate toxicity-or complication rates.

Six studies reported on patients receiving intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) [11,22,24-27]. All studies exclusively included patients with primary and or recurrent rectal cancer. Indications for application of IORT were a minimal circumferential free resection margin equal to or less than 2 mm in the study from Vermaas et al[11] and the concern for close and/or involved radial margins in the study by Gannon et al[28] Only 12 patients in the study by Vermaas et al[11] received IORT but no improvement in overall survival was seen.

In total seven publications included primary as well as recurrent rectal can-cers[6,9-11,26,28,29]. The studies by Gannon et al[28] Nielsen et al[9] and Vermaas et al[11] included 197 patients and only Gannon et al[28] reported that the disease setting was the only significant prognostic factor in favor of primary rectal cancers. This is in line with the results published by Rottoli et al[10] who also found the recurrent disease setting to be a negative prognostic factor.

MVR for gastric cancer (n = 16).

A total of 93 articles were identified using the aforementioned search algorithm (Figure 1). After full-text screening 16 studies were selected that met the inclusion criteria.

We identified 16 studies published between 1998 and 2019 describing MVR for a total of 1600 patients with locally advanced gastric cancer (Table 5). One publication reported patient- and treatment-related data after minimally-invasive MVR, whereas the other authors either performed open surgery or did not mention whether an open or laparoscopic approach was chosen[31]. The decision for or against suspected MVR, according to preoperative imaging modalities like CT, MRI, EUS and PET-CT, was made intraoperatively. Every verified adhesion of the primary tumor to adjacent structures was classified as a cT4b -situation. Together with a gastrectomy, mainly surrounding organs like spleen, pancreas or colon were resected. More rarely, the gallbladder or parts of the small bowel or the liver had to be removed.

| Study | Resection margin (R0 vs R1) | Most common resected organs | Lymph node involvement | Age | Blood transfusion | Complications (AI) (Re-OP) | Other prognostic factors |

| Carboni et al[39], 2005 | R0 61.5%; R1 27.7%; R2 10.8% | Spleen: 48%; Pancreas: 43%; Colon: 25% | 86.2% | 61 | NR | (1.5%) (1.5%) | Lymph-node involvement and metastatic disease |

| Colen et al[37], 2004 | NR | Spleen: 62%; Pancreas 57%; Colon: 24% | NR | 67.5 | NR | 0% (NR) | NR |

| D'Amato et al[38], 2004 | R0: 69% | Pancreas: 62%; Colon: 12% | NR | NR | NR | (0%) (NR) | NR |

| Jeong et al[43], 2009 | R0: 78.3%; R+: 21.7% | Spleen: 47%; Pancreas: 61%; Colon: 24% | N+: 90.1% | 59 | NR | (6.7%) (11%) | Lymph-node and lymphovascular involvement |

| Kim et al[35], 2009 | R0: 43%; R1: 15%; R2: 74% | Spleen: 38%; Pancreas: 29%; Colon: 56% | NR | NR | NR | (2.9%) (0%) | histologic type, M stage, peritoneal metastasis, curability and treatment groups |

| Martin et al[36], 2002 | R0: 100% | Spleen: 67%; Pancreas: 19%; Colon: 6%; Liver: 4% Gallbladder: 7% | N0: 35% N+: 65% | 66 | NR | (NR) (NR) | Lymph-node involvement and > pT3 |

| Oñate-Ocaña et al[32], 2008 | R0: 58.1%; R1: 18.9%; R2: 23% | Spleen: 68%; Pancreas: 26%; Colon: 12%; Liver: 9% | NR | NR | NR | (NR) (NR) | NR |

| Ozer et al[44], 2009 | NR | Pancreas: 54%; Colon: 32%; Liver: 18% | NR | 58 | NR | (8.9%) (NR) | Advanced age, lymph node involvement, and resection of more than 1 additional organ were significant prognostic factors for survival. |

| Persiani et al[46], 2008 | R0: 320; R1: 39; R2: 29% | Spleen: 84%; Pancreas: 25%; Colon: 10% | NR | 63.4 | NR | (NR) (NR) | Splenectomy, D2 lymphadenectomy, and age greater than 64 yr were the only factors predictive of overall morbidity |

| Shchepotin et al[33], 1998 | NR | Spleen: 43%; Pancreas: 69%; Colon: 45% Liver: 29% | N+: 38.8% | NR | NR | (3.7%) (NR) | NR |

| Isozaki et al[45], 2000 | NR | Pancreas + Spleen: 36%; Pancreatoduodenectomy: 7% | N0 = 13%; N1 = 36%; N2 = 25%; N3 = 12% | NR | NR | (NR) (NR) | Location of the tumor, lymph node metastasis, histological depth of invasion, and extent of lymph node dissection |

| Molina et al[40], 2019 | R0: 94% | Pancreas (49%); Spleen (34%) Liver (29%). | N+: 80% | 64,5 | NR | (NR) (NR) | Lymph-node involvement and R1-status |

| Mita et al[42], 2017 | R0: 82.5%; R1: 17.5% | Spleen 29.1%; Pancreas: 46.6%; Colon: 13.6%; Liver: 11.7% | N+: 84.5% | 70 | NR | (NR) (NR) | Resection status |

| Vladov et al[38], 2015 | R0: 75% | Spleen: 76.7%; Pancreas:40%; Colon: 18.3%; Liver 15% | NR | NR | NR | (NR) (NR) | NR |

| Tran et al[31], 2015 | R1: 15.5 | Spleen: 48%; Pancreas:27% Liver 14% Colon: 13% | N0: 34.5% | 64 | NR | (11.5%) (13.8%) | MVR with pancreatectomy, was significantly associated with decreased survival, along with T-stage, N stage, perineural invasion, and |

| Pacelli et al[34], 2013 | R0: 38.4% | Pancreas 46; Colon 43 | N+: 89.3% | NR | NR | (7%) (NR) | Lymph-node involvement and incomplete resection |

Prior clinically suspected T4-tumor was confirmed in 14%[32]-89.0%[33] of histo-pathological samples. Involvement of lymph nodes was described in 38.8%[33]-89.3%[34]) of patients.

The rate of morbidity ranged from 11.8%[35] to 59.8%[31] of patients who underwent gastrectomy and MVR (Table 6). Main postoperative complications were pancreatic fistulas and pancreatitis, anastomotic leakage, cardiopulmonary events and post-operative bleedings. Total mortality lay between 0%[35] and 13.6%[33]. R0-resections were achieved in 38.4%[34]-100%[36] of patients.

| Study | n | Follow-up (mo) | Morbidity (%) | Mortality (%) | Survival | Stage IV (%) | True pT4b (%) |

| Carboni et al[39], 2005 | 65 | 13 | 27.7 | 12.3 | OS: 21.8 mo | 46 | 80 |

| Colen et al[37], 2004 | 21 | NR | 39 | 10 | OS: 30 mo | NR | 38 |

| D'Amato et al[38], 2004 | 52 | NR | 34.6 | 1.9 | OS: 31 mo | NR | NR |

| Jeong et al[43], 2009 | 71 | 17.6 | 26.8 | NR | 3-yr OS: 36.4% | 76 | 63 |

| Kim et al[35], 2009 | 34 | NR | 11.8 | 0 | OS: 37.8 mo | 38 | NR |

| Martin et al[36], 2002 | 268 | NR | 39.2 | NR | OS: 63 mo | NR | 21 |

| Oñate-Ocaña et al[32], 2008 | 74 | NR | 26.9 | NR | OS: 30.5 mo | NR | 14-38 |

| Ozer et al[44], 2009 | 56 | 10.8 | 37.5 | 12.5 | 3-yr OS: 53.3% | 62 | 66 |

| Persiani et al[46], 2008 | 51 | NR | 16.2 | 2.3 | NR | 79 | 19.6 |

| Shchepotin et al[33], 1998 | 353 | NR | 31.2 | 13.6 | 5-yr OS: 25% | NR | 89.0 |

| Isozaki et al[45], 2000 | 86 | NR | NR | NR | 5-yr OS: 35% | NR | 53 |

| Molina et al[40], 2019 | 35 | 31 | 46 | 3 | 5-yr OS. 34% | NR | 40 |

| Mita et al[42], 2017 | 103 | 23.0 | 37.9 | 1.0 | 3-yr OS: 42.1% | 0 | 57 |

| Vladov et al[38], 2015 | 60 | NR | 28.3 | 6.7 | 5-yr OS: 24.1% | NR | 70 |

| Tran et al[31], 2015 | 159 | NR | 59.8 | 4.3 | 5-yr OS: MVR with pancreatectomy: 20%; MVR without: 36% | 0 | 67 |

| Pacelli et al[34], 2013 | 112 | 18.7 | 33.9 | 3,6 | 5-yr OS: 27.2% | NR | 88 |

Anastomotic insufficiency: Ten studies did not report the occurrence of anastomotic insufficiency (AI). The remainder reported AI -rates ranging from 0%[37,38] to 19.4%[31]. There was no structured report on management of AI in the studies included.

Re-operation: The rate of re-operation was only mentioned in 4 publications and ranged from 0%[37,38] to 13.8%[31].

Patients after R0 resection had 5 year overall survival rates of 24.1%[38] to 37.8%[35]. In the multivariate analysis, mostly incomplete resection status[34,39-42] as well as lymph node involvement[31,34,36,39,40,42-45] were found to be negative prognostic factors for survival. Further negative prognostic factors were metastasized stage[35,39], advanced age[44] the number of resected organs[31,42,44,46], no adjuvant chemotherapy[31] and white race[31].

MVR for locally advanced and adherent colorectal and gastric cancers seems to be a feasible approach that is associated with an acceptable morbidity - and mortality -rate and in a subset of patients good oncologic long-term results can be ob-tained[15,20,25,42,44,47]. Due to the reduced sensitivity and specificity of preoperative imaging for prediction of true malignant adhesion, the decision in favor of performing MVR is made intraoperatively in the vast majority of cases[1]. It is virtually impossible for the surgeon to differentiate between inflammatory and true malignant adhesions, so that every adherence to the tumor must be considered malignant and the appropriate operative strategy has to be applied. Data on intraoperative lysis of ad-hesions to the primary tumor, which were proven malignant by histopathological examination, revealed devastating overall survival rates and high local recurrence rates (Hunter et al[5]). In this review the true pT4b -rate varied from 23% to 77% and data on the impact of malignant invasion are heterogeneous with two studies[7,8] reporting no impact on overall-survival if malignant adhesions were detected and one study reporting the opposite[6]. It seems it is not the presence of proven malignant infiltration into adherent adjacent organs but the presence other tumor- and treatment-associated factors that are of prognostic importance. This review emphasized the importance of microscopic complete surgical resection, as one of the most predictive factors for overall- and recurrence-free survival[15,48]. These results are further highlighted by the results presented by Nielsen et al[9] comparing primary and recurrent rectal cancers. The authors stated that no statistically significant difference in overall survival was seen regarding the disease setting when comparing R0-resections. The remaining studies dealing with primary versus recurrent rectal cancer found the disease setting to be of significant prognostic impact[10,28]. Patient selection for MVR in the recurrent disease setting should be made on a case-by-case basis, because achievement of R0 -resection in these patients can also produce acceptable long-term results. The intraoperative assessment of truly preventing an R1 -resection is virtually not possible, but nevertheless palliative MVR should not be performed as shown by the data from Leijssen et al[2]. Authors reported for patients with proven T4 -cancers not undergoing MVR the highest local recurrence rate, namely 21.5% (compared to patients undergoing MVR: 14.5%) and the worst 5-year OS-and DFS rates (46.3% vs 52.7% vs 70% and 74.1%, respectively).

Apart from the completeness of surgical resection factors like lymph -node and lymphovascular involvement seem to be predictive for survival. López-Cano et al[49], Smith et al[47] and Harris et al[19] showed that lymphatic spread was associated with worse prognosis. Cukier et al[24] and Dinaux et al[50] discussed the significance of the ypN -stage. Cukier et al[24] reported no statistical difference in terms of DFS when comparing ypN0 and ypN1 patients. Contrarily, Dinaux et al[50] showed that ypN+ status was significantly associated with overall mortality. Hoffmann et al[21] found no difference in terms of OS for pN0 versus pN1 patients after MVR for primary co-lorectal cancers.

The role of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemo- (radio-) therapy in short- and long-term results was hardly assessable due to the heterogeneity of data provided. The study by Sanfilippo et al[26] showed no significant association between application of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and local pelvic control rate. Dinaux et al[50] even found the performance of adjuvant chemotherapy to be significantly associated with overall mortality.

The significance of minimally-invasive MVR was highlighted in a couple of studies (Table 4). The laparoscopic approach for standard -resections for colon - and gastric cancer has already become accepted with low morbidity rates and comparable oncologic long-term results. The acceptance of laparoscopic or robotic MVR is low but the minimally-invasive approach seems to harbor some advantages over the open approach. Table 4 sums up the most important studies, highlighting the fact that minimally-invasive MVR is associated with a reduced operative time, reduced blood loss and transfusion requirement. The conversion rates were low by a comparable lymph-node harvest. Prior to scheduling patients for minimal-invasive MVR, relative contraindications like excessive small bowel- and urologic tract involvement should receive attention.

Our analysis of the so far published results of MVR for patients with locally advanced gastric cancer shows 5-year survival rates of 24.1%-37.8% for patients with an R0-resection, while the rate of morbidity was 11.8% to 59.8% and the rate of mortality 0-15%. The authors of these studies therefore consider MVR for locally advanced gastric cancer to be a potentially beneficial procedure, especially if there is a possibility of curative resection.

Comparable results can also be found for MVR of other abdominal tumor entities such as neuroendocrine tumors or gastrointestinal stroma tumors[51]. Similar ap-proaches were also investigated for locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal cancer. With the acceptance of higher rates of morbidity and longer operating times MVR for locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma may lead to a long -term survival comparable to that for standard resections of the pancreas[52].

In conclusion, the main limitation of this review is the mainly retrospective studies included and the heterogeneity in reporting short- and long-term outcomes. Nevertheless, MVR for primary cancers are of significant importance in oncologic surgery providing acceptable morbidity- and mortality rates with good long-term survival for selected patients. Negative selection criteria are incomplete surgical resection, recurrent rectal cancer, and lymph-node and lymphovascular involvement. Stage-IV disease should be regarded as a relative contraindication for MVR.

Multivisceral resections (MVR) still constitute a challenge for the interdisciplinary team. The indications to perform MVR are not clearly defined.

Motivation was generated by the fact that there are no recommendations regarding MVR.

In order to define indications and factors associated with beneficial oncologic outcomes and reduced perioperative morbidity and mortality this systematic review was conducted.

We performed a PubMed-search from 2000 to 2018 including articles reporting on MVR in pa-tients with colon-, rectal- and gastric cancer.

Available data shows that MVR from locally advanced colorectal and gastric cancer is a feasible option which is associated with acceptable morbidity- and mortality-rates. Oncologic outcome is favorable when clear resection margins can be obtained.

Patients who are clinically fit and preoperative imaging does not reveal obvious contraindication for radical surgery, the option of MVR should not be abandoned. Clear resection margins are the main goal of aggressive surgical approach.

Perspectives are to evaluate more patient- and treatmenspecific parameters in order to define more clearly patients who are likely to benefit from this approach.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kitai C S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Winter DC, Walsh R, Lee G, Kiely D, O'Riordain MG, O'Sullivan GC. Local involvement of the urinary bladder in primary colorectal cancer: outcome with en-bloc resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Leijssen LGJ, Dinaux AM, Amri R, Kunitake H, Bordeianou LG, Berger DL. The Impact of a Multivisceral Resection and Adjuvant Therapy in Locally Advanced Colon Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:357-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13930] [Cited by in RCA: 13302] [Article Influence: 831.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Borowski DW, Bradburn DM, Mills SJ, Bharathan B, Wilson RG, Ratcliffe AA, Kelly SB; Northern Region Colorectal Cancer Audit Group (NORCCAG). Volume-outcome analysis of colorectal cancer-related outcomes. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1416-1430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hunter JA, Ryan JA, Schultz P. En bloc resection of colon cancer adherent to other organs. Am J Surg. 1987;154:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Chen YG, Liu YL, Jiang SX, Wang XS. Adhesion pattern and prognosis studies of T4N0M0 colorectal cancer following en bloc multivisceral resection: evaluation of T4 subclassification. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;59:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rosander E, Nordenvall C, Sjövall A, Hjern F, Holm T. Management and Outcome After Multivisceral Resections in Patients with Locally Advanced Primary Colon Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:454-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lehnert T, Methner M, Pollok A, Schaible A, Hinz U, Herfarth C. Multivisceral resection for locally advanced primary colon and rectal cancer: an analysis of prognostic factors in 201 patients. Ann Surg. 2002;235:217-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nielsen MB, Rasmussen PC, Lindegaard JC, Laurberg S. A 10-year experience of total pelvic exenteration for primary advanced and locally recurrent rectal cancer based on a prospective database. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1076-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rottoli M, Vallicelli C, Boschi L, Poggioli G. Outcomes of pelvic exenteration for recurrent and primary locally advanced rectal cancer. Int J Surg. 2017;48:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vermaas M, Ferenschild FT, Verhoef C, Nuyttens JJ, Marinelli AW, Wiggers T, Kirkels WJ, Eggermont AM, de Wilt JH. Total pelvic exenteration for primary locally advanced and locally recurrent rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:452-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Takahashi R, Hasegawa S, Hirai K, Hisamori S, Hida K, Kawada K, Sakai Y. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic multivisceral resection for surgical T4b colon cancers: Retrospective analyses. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2017;10:154-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mañas MJ, Espín E, López-Cano M, Vallribera F, Armengol-Carrasco M. Multivisceral Resection for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Prognostic Factors Influencing Outcome. Scand J Surg. 2015;104:154-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pellino G, Biondo S, Codina Cazador A, Enríquez-Navascues JM, Espín-Basany E, Roig-Vila JV, García-Granero E; Rectal Cancer Project. Pelvic exenterations for primary rectal cancer: Analysis from a 10-year national prospective database. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:5144-5153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kumamoto T, Toda S, Matoba S, Moriyama J, Hanaoka Y, Tomizawa K, Sawada T, Kuroyanagi H. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic Multivisceral Resection for Clinically Suspected T4 Colon Cancer. World J Surg. 2017;41:2153-2159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li JC, Chong CC, Ng SS, Yiu RY, Lee JF, Leung KL. En bloc urinary bladder resection for locally advanced colorectal cancer: a 17-year experience. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1169-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim KY, Hwang DW, Park YK, Lee HS. A single surgeon's experience with 54 consecutive cases of multivisceral resection for locally advanced primary colorectal cancer: can the laparoscopic approach be performed safely? Surg Endosc. 2012;26:493-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gezen C, Kement M, Altuntas YE, Okkabaz N, Seker M, Vural S, Gumus M, Oncel M. Results after multivisceral resections of locally advanced colorectal cancers: an analysis on clinical and pathological t4 tumors. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Harris DA, Davies M, Lucas MG, Drew P, Carr ND, Beynon J; Swansea Pelvic Oncology Group. Multivisceral resection for primary locally advanced rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2011;98:582-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hallet J, Zih FS, Lemke M, Milot L, Smith AJ, Wong CS. Neo-adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and multivisceral resection to optimize R0 resection of locally recurrent adherent colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:706-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hoffmann M, Phillips C, Oevermann E, Killaitis C, Roblick UJ, Hildebrand P, Buerk CG, Wolken H, Kujath P, Schloericke E, Bruch HP. Multivisceral and standard resections in colorectal cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:75-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shin US, Nancy You Y, Nguyen AT, Bednarski BK, Messick C, Maru DM, Dean EM, Nguyen ST, Hu CY, Chang GJ. Oncologic Outcomes of Extended Robotic Resection for Rectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2249-2257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tei M, Otsuka M, Suzuki Y, Kishi K, Tanemura M, Akamatsu H. Safety and feasibility of single-port laparoscopic multivisceral resection for locally advanced left colon cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:10091-10097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cukier M, Smith AJ, Milot L, Chu W, Chung H, Fenech D, Herschorn S, Ko Y, Rowsell C, Soliman H, Ung YC, Wong CS. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and multivisceral resection for primary locally advanced adherent colon cancer: a single institution experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:677-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Crawshaw BP, Augestad KM, Keller DS, Nobel T, Swendseid B, Champagne BJ, Stein SL, Delaney CP, Reynolds HL. Multivisceral resection for advanced rectal cancer: outcomes and experience at a single institution. Am J Surg. 2015;209:526-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sanfilippo NJ, Crane CH, Skibber J, Feig B, Abbruzzese JL, Curley S, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Hoff P, Wolff RA, Brown TD, Cleary K, Wong A, Phan T, Janjan NA. T4 rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiation to the posterior pelvis followed by multivisceral resection: patterns of failure and limitations of treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:176-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vladov N, Lukanova TS, Trichkov Ts, Takorov I, Mihaylov V, Vasilevski I, Odiseeva E. MULTIVISCERAL RESECTIONS FOR GASTRIC CANCER. Khirurgiia (Sofiia). 2015;81:116-122. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Gannon CJ, Zager JS, Chang GJ, Feig BW, Wood CG, Skibber JM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA. Pelvic exenteration affords safe and durable treatment for locally advanced rectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1870-1877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fujisawa M, Nakamura T, Ohno M, Miyazaki J, Arakawa S, Haraguchi T, Yamanaka N, Yao A, Matsumoto O, Kuroda Y, Kamidono S. Surgical management of the urinary tract in patients with locally advanced colorectal cancer. Urology. 2002;60:983-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dosokey EMG, Brady JT, Neupane R, Jabir MA, Stein SL, Reynolds HL, Delaney CP, Steele SR. Do patients requiring a multivisceral resection for rectal cancer have worse oncologic outcomes than patients undergoing only abdominoperineal resection? Am J Surg. 2017;214:416-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tran TB, Worhunsky DJ, Norton JA, Squires MH, Jin LX, Spolverato G, Votanopoulos KI, Schmidt C, Weber S, Bloomston M, Cho CS, Levine EA, Fields RC, Pawlik TM, Maithel SK, Poultsides GA. Multivisceral Resection for Gastric Cancer: Results from the US Gastric Cancer Collaborative. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S840-S847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Oñate-Ocaña LF, Becker M, Carrillo JF, Aiello-Crocifoglio V, Gallardo-Rincón D, Brom-Valladares R, Herrera-Goepfert R, Ochoa-Carrillo F, Beltrán-Ortega A. Selection of best candidates for multiorgan resection among patients with T4 gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:336-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shchepotin IB, Chorny VA, Nauta RJ, Shabahang M, Buras RR, Evans SR. Extended surgical resection in T4 gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 1998;175:123-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pacelli F, Cusumano G, Rosa F, Marrelli D, Dicosmo M, Cipollari C, Marchet A, Scaringi S, Rausei S, di Leo A, Roviello F, de Manzoni G, Nitti D, Tonelli F, Doglietto GB; Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer. Multivisceral resection for locally advanced gastric cancer: an Italian multicenter observational study. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:353-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kim JH, Jang YJ, Park SS, Park SH, Kim SJ, Mok YJ, Kim CS. Surgical outcomes and prognostic factors for T4 gastric cancers. Asian J Surg. 2009;32:198-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | RC 2nd, Jaques DP, Brennan MF, Karpeh M. Extended local resection for advanced gastric cancer: increased survival versus increased morbidity. Ann Surg. 2002;236:159-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Colen KL, Marcus SG, Newman E, Berman RS, Yee H, Hiotis SP. Multiorgan resection for gastric cancer: intraoperative and computed tomography assessment of locally advanced disease is inaccurate. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:899-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | D'Amato A, Santella S, Cristaldi M, Gentili V, Pronio A, Montesani C. The role of extended total gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:609-612. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Carboni F, Lepiane P, Santoro R, Lorusso R, Mancini P, Sperduti I, Carlini M, Santoro E. Extended multiorgan resection for T4 gastric carcinoma: 25-year experience. J Surg Oncol. 2005;90:95-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Molina JC, Al-Hinai A, Gosseling-Tardif A, Bouchard P, Spicer J, Mulder D, Mueller CL, Ferri LE. Multivisceral Resection for Locally Advanced Gastric and Gastroesophageal Junction Cancers-11-Year Experience at a High-Volume North American Center. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Fujiwara T, Hizuta A, Iwagaki H, Matsuno T, Hamada M, Tanaka N, Orita K. Appendiceal mucocele with concomitant colonic cancer. Report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:232-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mita K, Ito H, Katsube T, Tsuboi A, Yamazaki N, Asakawa H, Hayashi T, Fujino K. Prognostic Factors Affecting Survival After Multivisceral Resection in Patients with Clinical T4b Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:1993-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Jeong O, Choi WY, Park YK. Appropriate selection of patients for combined organ resection in cases of gastric carcinoma invading adjacent organs. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ozer I, Bostanci EB, Orug T, Ozogul YB, Ulas M, Ercan M, Kece C, Atalay F, Akoglu M. Surgical outcomes and survival after multiorgan resection for locally advanced gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2009;198:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Isozaki H, Tanaka N, Tanigawa N, Okajima K. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced gastric cancer with macroscopic invasion to adjacent organs treated with radical surgery. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:202-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Persiani R, Antonacci V, Biondi A, Rausei S, La Greca A, Zoccali M, Ciccoritti L, D'Ugo D. Determinants of surgical morbidity in gastric cancer treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:13-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Smith JD, Nash GM, Weiser MR, Temple LK, Guillem JG, Paty PB. Multivisceral resections for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1137-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Derici H, Unalp HR, Kamer E, Bozdag AD, Tansug T, Nazli O, Kara C. Multivisceral resections for locally advanced rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:453-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | López-Cano M, Mañas MJ, Hermosilla E, Espín E. Multivisceral resection for colon cancer: analysis of prognostic factors. Dig Surg. 2010;27:238-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Dinaux AM, Leijssen LGJ, Bordeianou LG, Kunitake H, Berger DL. Effects of local multivisceral resection for clinically locally advanced rectal cancer on long-term outcomes. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117:1323-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Hasselgren K, Sandström P, Gasslander T, Björnsson B. Multivisceral Resection in Patients with Advanced Abdominal Tumors. Scand J Surg. 2016;105:147-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 52. | Hartwig W, Hackert T, Hinz U, Hassenpflug M, Strobel O, Büchler MW, Werner J. Multivisceral resection for pancreatic malignancies: risk-analysis and long-term outcome. Ann Surg. 2009;250:81-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Park S, Lee YS. Analysis of the prognostic effectiveness of a multivisceral resection for locally advanced colorectal cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2011;27:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Ishiguro S, Akasu T, Fujita S, Yamamoto S, Kusters M, Moriya Y. Pelvic exenteration for clinical T4 rectal cancer: oncologic outcome in 93 patients at a single institution over a 30-year period. Surgery. 2009;145:189-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Bannura GC, Barrera AE, Cumsille MA, Contreras JP, Melo CL, Soto DC, Mansilla JE. Posterior pelvic exenteration for primary rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:309-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Laurence G, Ahuja V, Bell T, Grim R, Ahuja N. Locally advanced primary recto-sigmoid cancers: Improved survival with multivisceral resection. Am J Surg. 2017;214:432-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Rizzuto A, Palaia I, Vescio G, Serra R, Malanga D, Sacco R. Multivisceral resection for occlusive colorectal cancer: Is it justified? Int J Surg. 2016;33 Suppl 1:S142-S147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Eveno C, Lefevre JH, Svrcek M, Bennis M, Chafai N, Tiret E, Parc Y. Oncologic results after multivisceral resection of clinical T4 tumors. Surgery. 2014;156:669-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |