Published online Aug 26, 2017. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v5.i4.85

Peer-review started: February 12, 2017

First decision: March 8, 2017

Revised: May 3, 2017

Accepted: May 12, 2017

Article in press: May 15, 2017

Published online: August 26, 2017

Processing time: 208 Days and 18.6 Hours

To summarize the current consensus on the definition of remission and the endpoints employed in clinical trials.

A bibliogragraphic search was performed from 1946 to 2016 sing online databases (National Library of Medicine’s PubMed Central Medline, OVID SP MEDLINE, OVID EMBASE, the Cochrane Library and Conference Abstracts) with key words: (“ulcerative colitis”) AND (“ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity” OR “UCEIS”) AND (“remission”) as well as (“ulcerative colitis”) AND (“ulcerative colitis disease activity index”) OR “UCDAI” OR “UC disease activity index” OR “Sutherland index”) AND (“remission”).

The search returned 37 and 116 articles for the UCEIS and UCDAI respectively. For the UCEIS, 12 articles were cited in the final analysis of which 9 validation studies have been identified. Despite the UCEIS has been more extensively validated in all three aspects (validity, responsiveness and reliability), it has been little employed to monitor disease in randomised clinical trials. For the UCDAI, 37 articles were considered for the final analysis. Although the UCDAI is only partially validated, 29 randomised clinical trials were acknowledged to use the UCDAI to determine endpoints and disease remission, though no clear protocol was identified.

Although the UCEIS has been more widely validated than the UCDAI, it has not been reflected in the monitoring of disease activity in clinical trials. Conversely, the UCDAI has been used in numerous large clinical trials to define their endpoints and disease remission, however, it is challenging to determine the best possible outcomes due to a lack of homogeneity of the clinical trial protocols. Before determining a gold standard index, international agreement on remission is urgently needed to advance patient care.

Core tip: Despite the decades of discussion, disease remission for ulcerative colitis has yet to be fully defined. Instead, numerous indices that measure a large variety of endpoints had been developed, each claiming to be accurate and informative. This systematic review aimed to summarise the issues related to the uncertain definition of disease remissions in clinical trial studies by focusing on two indices ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity and ulcerative disease activity index. We recommend that an international consensus of remission should be sought before establishing a gold standard outcome measurement to untangle this confusion.

- Citation: Jitsumura M, Kokelaar RF, Harris DA. Remission endpoints in ulcerative colitis: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal 2017; 5(4): 85-102

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v5/i4/85.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v5.i4.85

How do we determine remission as an endpoint in ulcerative colitis (UC) clinical trials when we design a study? There is no universally agreed definition of remission as an endpoint in UC clinical trials as of date, despite much discussion and urge for the standardisation. Currently, it is chosen to reflect the purpose of the studies, rather than long-term clinical outcomes or controlling bothersome symptoms that patients often suffer from. Furthermore, a lack of homogeneity of the clinical trial protocols makes comparison of such studies more difficult to comprehend.

UC is a chronic relapsing-remitting inflammatory bowel disease, affecting mucosa of the large bowel. Patients with UC often present with debilitating symptoms such as abdominal pain and rectal bleeding. Although the aetiology of UC is believed to be multifactorial involving dysregulated immune system, intestinal mucosal disturbance and genetic predisposition, natural history of the disease is poorly understood[1]. There is no curative treatment at present, thus the aim of management is induction and maintenance of remission with immunosuppressive agents, permitting individuals to carry on their daily life. The failure of medical therapy or refractory disease often require colorectal surgery, and there is an increased risk of colorectal cancer[2].

Since the first disease activity outcome measurement was developed in 1955, the Truelove and Witts Index, numerous outcome measure instruments have been developed[3]. Not only has the number of these instruments been growing, but also the assessed disease components have been expanding. Traditionally, disease activity has been assessed by a clinical and symptom scoring system, with or without a combined endoscopic assessment. A recent review counted seventeen clinical disease activity indices which evaluate symptoms, of which eight do so without endoscopic or biomarker assessment[4]. The purpose of these disease activity indices is to provide an objective measurement of the disease activity by employing typical symptoms such as stool frequency and rectal bleeding. Endoscopic assessment is another dimension of the disease that is mandated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)[5] and at least thirty-one instruments were proposed[6]. Many of these endoscopic indices, such as Mayo score and ulcerative colitis disease activity index (UCDAI), evaluate the macroscopic appearance of large bowel, together with symptomatic disease activity. Recently, the prognostic potential of histological assessment in UC has been highlighted in several studies[7-9], although histological remission has yet to be proposed as a therapeutic endpoint for clinical trials or practice, twenty-six histological activity indices have been developed thus far. It is important to note that there is considerable disparity between visual endoscopic assessment and histological disease activity[9], although confusingly these terms are used interchangeably[9]. In addition to symptomatology, endoscopic, and histological scoring systems, radiological outcome instruments as well as new biochemical markers are an additional developing dimension of disease assessment[4].

In addition to these objective indices, we cannot neglect patient subjective outcome measurement tools and quality of life (QoL) questionnaires. The aim of these tools is to evaluate the patients’ emotional, social or professional well-being so that their ideas, concerns, and expectations can be a part of the objective medical decision-making process. Patients often have different expectations of treatment and remission from those of physicians, and symptoms used in established scoring tools may be of relatively little concerns to some individuals. Establishing an understanding of chronicity is also important in assessing a patient’s disease, especially when reconciling the long term treatment goals with a patients’ concerns regarding how quickly embarrassing, troublesome and physical symptoms can be resolved with minimal side effects[10]. Furthermore, we cannot underestimate the power of the internet and smartphone use in medicine; many patients often seek online diagnosis of their symptoms before they are formally assessed by a clinician, and may already be either well informed or misguided when discussing management. Patients often use “remission” and “flare-ups” informally to describe their disease activity without reference to formal assessments of such, and thus misunderstandings may occur when discussing assessment and treatment. A few self-reporting assessment tools (smartphone apps) are available, allowing patients to monitor their disease activity on daily basis in a more objective manner[11]. Whether these patient-reported measurement instruments show a good correlation with true disease activity by other measures appears to be almost irrelevant. Many patients with asymptomatic UC do not feel the need of continuing medications in the absence of discernible symptoms, especially when they give side effects, making the negotiation more challenging for clinicians. A good rapport and the ability to reach negotiated consensus with patients is an integral skill for clinicians managing complex UC patients.

The overall picture is that there are numerous indices that measure a large variety of endpoints, each claiming to be accurate and informative regarding one or other management goal. Confusingly, these indices share similar names or are often referred to by multiple names or abbreviations, such as the UCDAI which is also referred to as the Sutherland Index. Unfortunately, no single scoring system provides comprehensive assessment of disease activity, and the majority of these indices lack robust clinical validation. Most clinical trials, from which the scoring systems are derived, choose disease outcome measures and endpoints reflecting the purpose of the studies, rather than long-term clinical outcomes or real-world symptom control for patients. Furthermore, each clinical trial defines remission differently, making comparison between different trials difficult.

The consequence of the complexity in UC outcome measurements and the huge variety in competing scoring systems is that many patients with UC may receive suboptimal therapy and poor long-term disease control.

This systematic review will reassess and summarise the current consensus on the definition of remission and the endpoints employed in clinical trials by focusing on two most validated and well-used indices, the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) and UCDAI, in order to address the issues with the standardisation of clinical trial protocols.

The current target of disease remission endoscopically is mucosal healing although it has not been fully validated or no standardised definition of mucosal healing[12,13]. Yet, this appears to be the goal for many clinical practice as well as drug trials.

The recent draft guideline released by the FDA[5] states the ideal primary efficacy assessment instrument in clinical trials should consist of (1) a signs and symptoms assessment scale - best measured by a patient-reported outcome instrument. If not, an observer-reported outcome instrument; and (2) an endoscopic and histological assessment scale.

Thus, endoscopic assessment tools with comprehensive clinical symptom assessment components that come from patients would be a reasonable choice to argue remission and endpoints employed in clinical trials.

Amongst numerous endoscopic indices claiming to measure disease activity, the UCEIS is one of the most widely validated indices to date. It would be interesting to see any impact of the quality of validation for defining remission and endpoints compared with the index, such as the UCDAI, that has not been fully validated yet being widely employed in clinical trials. For these reasons, these two indices were chosen for this systematic review.

The UCEIS proposed by Travis et al[14] in 2012 is the only validated endoscopic index in ulcerative colitis to date[15]. It was developed to minimise variation in endoscopic assessment, thus it could be widely applied as a reliable outcome measure in clinical trials as well as clinical settings.

The first stage of development of the UCEIS demonstrated the significant inconsistency in endoscopic assessment amongst specialists by 10 specialists scoring the severity of UC using the Baron score[16] in colonoscopy videos. The greatest correlation was found in the “severe” level of the Baron score, demonstrating a 76% agreement, however, only 27% agreement was achieved for a normal mucosa (Baron score 0) and 37% agreement for moderate friability (Baron score 2).

The second part of the study further quantifies intra- and inter-observer variation on common descriptors on endoscopic assessments (Table 1). For intra-observer variation, 60 repeat pair assessment of 36 different videos were scored and assessed by κ statistics. For inter-observer variation, 30 new investigators were randomly allocated to score 25 videos, thus each video was assessed by 10-12 investigators.

| Descriptor | Likert scale anchor points | Intra-observer variation(a weighted k) | Inter-observer variation (a weighted k) |

| Vascular pattern | Normal (1) Patchy loss (3) Obliterated (5) | 0.61 | 0.42 |

| Mucosal erythema | None (1) | 0.43 | 0.35 |

| Light red (3) | |||

| Dark red (5) | |||

| Mucosal surface (Granularity) | Normal (1) | 0.45 | 0.34 |

| Granular (3) | |||

| Nodular (5) | |||

| Mucosal oedema | None (1) | 0.43 | 0.31 |

| Probable (3) | |||

| Definite (5) | |||

| Mucopus | None (1) | 0.47 | 0.4 |

| Some (3) | |||

| Lots (5) | |||

| Bleeding | None (1) | 0.57 | 0.37 |

| Mucosal (2) | |||

| Luminal mild (3) | |||

| Luminal moderate (4) | |||

| Luminal severe (5) | |||

| Incidental friability | None (1) | 0.49 | 0.4 |

| Mild (2) | |||

| Moderate (3) | |||

| Severe (4) | |||

| Very severe (5) | |||

| Contact friability | None (1) | 0.34 | 0.3 |

| Probable (3) | |||

| Definite (5) | |||

| Erosions and ulcers | None (1) | ||

| Erosions (2) | 0.65 | 0.45 | |

| Superficial ulcer (3) | |||

| Deep ulcer (4) | |||

| Extent of erosions or ulcers | None (1) | 0.6 | 0.42 |

| Limited (2) | |||

| Substantial (3) | |||

| Extensive (4) |

Both intra- and inter-observer variation showed good agreement to assess erosions and ulcers, vascular pattern and bleeding, which were subsequently chosen for descriptors of a newly developed endoscopic assessment tool, the UCEIS (Table 2).

| Descriptors | Likert Scale anchor point | Definition |

| Vascular pattern | 0: Normal 1: Patchy obliteration 2: Complete obliteration | Normal vascular pattern with arborisation of capillaries clearly defined, or with blurring or patchy loss of capillary margins Complete obliteration |

| Bleeding | 0: None 1: Mucosa 2: Luminal mild 3: Luminal moderate or severe | Some spots or streaks of coagulated blood on the surface of the mucosa Some free liquid blood in the lumen Frank blood in the lumen ahead of endoscope or visible oozing from a haemorrhagic mucosa |

| Erosions and Ulcers | 0: None 1: Erosions | None Tiny < 5 mm defects in the mucosa, of white or yellow colour with a flat edge |

| 2: Superficial ulcer | Larger > 5 mm defect in the mucosa, which are discrete fibrin-covered ulcers in comparison with erosions, but remain superficial | |

| 3: Deep ulcer | Deeper excavated defects in the mucosa, with a slightly raised edge |

The authors also proposes definition of remission using the UCEIS, which is when all three descriptors were level 1 (no visible bleeding or erosions or ulceration, but some blurring or loss of capillary margins with a recognisable vascular pattern is allowed).

The UCDAI (also called UC Disease Activity Index, and Sutherland Index) was introduced by Sutherland et al[17] to assess efficacy of 5-aminosalicylic acid enema in the treatment of distal UC in its randomized, double-blind clinical trial in 1987.

The index was used for objective assessment during this drug trial and considers four variables of UC - stool frequency, rectal bleeding, mucosal appearance and physician’s rating of disease activity (Table 3). Unlike the UCEIS, the UCDAI was developed without any validated study. Although the authors described that the index incorporates many of the subscales used by other investigators and demonstrated efficacy as an overall index and individual component subscale, they failed to demonstrate this with any form of statistical assessment. Furthermore, they also compared between the overall index and the physician’s global assessment by this drug trial study physician and concluded that the UCDAI demonstrates good correlation with the physician’s assessment (P = 0.0001). This conclusion fails to demonstrate objectivity although the authors’ fundamental aim of designing this index was to provide objective assessment.

| Variables | Score | Items |

| Stool frequency | 0 | Normal |

| 1 | 1-2 stools/d more than normal | |

| 2 | 3-4 stools/d more than normal | |

| 3 | > 4 stools/d more than normal | |

| Rectal bleeding | 0 | None |

| 1 | Streaks of blood | |

| 2 | Obvious blood | |

| 3 | Mostly blood | |

| Endoscopic appearance | 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Mild friability | |

| 2 | Moderate friability | |

| 3 | Exudation, spontaneous bleeding | |

| Physician global assessment | 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Mild | |

| 2 | Moderate | |

| 3 | Severe |

The UCEIS was developed based on components to minimise the variation identified in previous endoscopic assessment instruments. It has been validated from various angles at the time of designing, making it more reliable than traditional instruments. Conversely, the UCDAI was designed without any validated evidence to assess efficacy of a drug for treatment of UC. Yet, it has been widely used in numerous clinical trials for decades and even recommended by the FDA as one of the endoscopic assessment tools.

A systematic bibliographic search was performed between 10th and 14th November 2016 of the following online databases: OVID SP MEDLINE (1946 to present), OVID EMBASE (1974 to present), National Library of Medicine’s PubMed Central MEDLINE (1950 to present), the Cochrane Library, using the key heading-words strategy set below and the medial subject heading. The bibliographies of recovered systematic review, meta-analysis, and review articles were also searched for additional articles.

Each database was searched for the following headings: (1) Ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity: (“ulcerative colitis”) AND (“ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity” OR “UCEIS”) AND (“remission”); and (2) Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index: (“ulcerative colitis”) AND (“Ulcerative colitis disease activity index” OR “UC disease activity index” OR “UCDAI” OR “Sutherland index”) AND (“remission”)

Non-English articles, studies pertaining to paediatric subjects, and non-human subjects were excluded. Studies presenting data of patient populations already included in other publication (duplicates) were excluded. No abstract publications without subsequent full-text published data were used. Disagreements about inclusion were resolved in a consensus meeting.

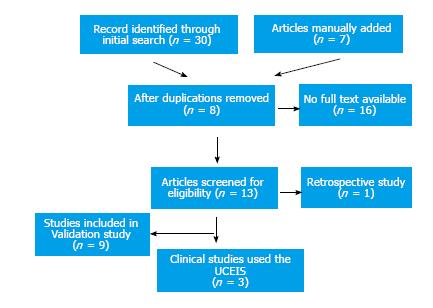

A total of 37 articles were returned using the initial search. After applying exclusion criteria and eliminating duplication, 12 articles screened for relevance and manual search of articles referenced in the retrieved articles was performed. Nine articles were included in the final analysis for validation assessment of UCEIS and 3 articles were evaluated for the UCEIS use in clinical trials (Figure 1).

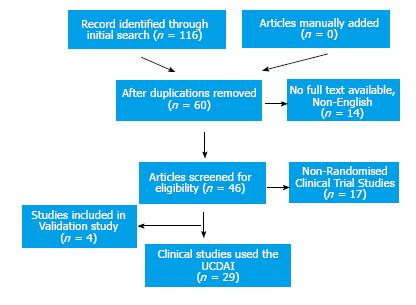

A total of 116 articles were returned using the initial search, which was down to 37 articles after considering exclusion criteria and duplication. Four articles were identified for the final analysis of validation assessment and 29 articles were included to evaluate defining remission and endpoints of clinical trials (Figure 2).

The definition of disease remission has not yet been validated or standardised. Inevitably, implementing clinical scoring tools based on a broad definition of remission results in inaccuracy of outcomes, and a reduction in the utility of a derived tool. The gold standard for disease activity in UC must be a diagnostic tool that truly quantifies the disease activity and can accurately assess and therefore guide future disease managements and outcome. A robust and standardised outcome measurement instrument is vital for clinical trials and establishment of medical therapy, although many instruments are not fully validated.

In this systematic review, validation of UCEIS and UCDAI studies were described by dividing into validity, reproducibility and responsiveness (Table 4).

| Ref. | Patient number | Outcomes | |

| UCEIS | |||

| Validity | Corte et al[18] | 89 | Correlation between UCEIS and outcomes The UCEIS score was directly proportional to requirement of rescue therapy UCEIS ≥ 5 was significantly linked to requiring colectomy 18/54 (33%) patients with UCEIS ≥ 5 compared to 3/33 (9%) with UCEIS ≤ 4 No definition of remission |

| Fernandes et al[19] | 108 | Prediction of outcomes in acute severe colitis UCEIS was applied to score of the rectum and sigmoid, seg-UCEIS Seg-UCEIS predicted to develop steroid-refractory disease and the likelihood of colectomy (seg-UCEIS = 14 had a 17 times higher risk of steroid-refractory disease and a 25 times higher risk of requiring colectomy) Every 1 point increase in the UCEIS or Seg-UCEIS increased the need of colectomy by 2.78 and 1.79 respectively Mayo score did not predict these No definition of remission | |

| Arai et al[20] | 285 | Reflection of true UC activity and remission The recurrence rate was directly proportional to the UCEIS score (5.0% for UCEIS = 0, 22.4% for UCEIS = 1, 27.0% for UCEIS = 2, 35.7% for UCEIS = 3, 75% for UCEIS = 4-5) The absence of bleeding and mucosal damage were independent factors for continued clinical remission UCEIS ranged from 0 to 5 when clinical remission, Mayo ≤ 1 UCEIS ≤ 1 for clinical remission, which showed sensitivity of 68% and specificity 57% The expected duration of recurrence is also prolonged when UCEIS ≤ 1 | |

| Kucharski et al[21] | 49 | Assessment of 9 endoscopic indices correlate well with (1) clinical indices; and (2) histological Geboes Index[22] The UCEIS showed the strongest correlation with the Geboes Index (the coefficient: 0.434 to 0.629) Recommends the UCEIS for the best overall correlations with both clinical and histological indices | |

| Responsiveness | Ikeya et al[23] | 41 | The ability to detect to change after Tacrolimus remission induction treatment for moderate to severe UC Although Mayo endoscopic score is easy to use, it does not distinguish depth of ulcers unlike UCEIS Despite UCEIS score improved from 7 to 4, Mayo endoscopic score remained at 3 (severe) An improvement of UCEIS ≥ 3 showed close correlation with clinical remission, colectomy-free and relapse free rates Proposed remission (score 0-1), mild (2-4), moderate (5-6), severe (7-8) UCEIS 1 in remission is only from vascular pattern |

| Menasci et al[24] | 80 | Comparison of the global UCEIS score from 5 segments and a traditional method of UCEIS score The regular method of the UCEIS is to score the most inflamed segment of the bowel This was compared with the sum of the score of five colonic segments A very good correlation (Spearman’s r = 0.86, P < 0.0001) for disease with UCEIS score ≤ 5 Less correlation (r = 0.48, P < 0.01) for disease with UCEIS > 5 | |

| Reliability | Travis et al[15] | Investigation of intra- and inter-observer consistency assessment 25 readers evaluated 28 videos including 4 duplicates to assess intra-reader reliability The intra and inter-reader reliability ratios for the UCEIS were 0.96 and 0.88 respectively The USCEI revealed a strong correlation with overall assessment of severity without being influenced by knowledge of clinical information No definition of remission | |

| Feagan et al[25] | 281 | The effect of centralized review of images on inter-observer variations Patients with UCDAI ≥ 2 were randomised to evaluate the efficacy of delayed mesalamine treatment (4.8 g/d for 10 wk) UCEIS was used as a part of inter-observer agreement study and showed interclass correlation coefficient of 0.83 amongst 7 central readers, which is superior to UCDAI | |

| Travis et al[26] | Clinical information influences UCEIS score 40 readers evaluated 28 of 44 videos No discrepancy between blinded and unblended readers Intra- and inter-reader variability demonstrated moderate to substantial agreement (κ = 0.47 to 0.74 and κ = 0.40 to 0.50 respectively) UCEIS correlated well with patient-reported symptoms - rectal bleeding, stool frequency and patient functional assessment (rank correlation = 0.76 to 0.82) | ||

| UCDAI | |||

| Validity | Higgins et al[27] | 66 | Finding endpoints in disease activity indices for remission and improvement in UC UCDAI < 2.5 for remission, which had a sensitivity and specificity of 0.82 and 0.89 Remission in this study was defined by patients |

| Poole et al[28] | 126 | Establish the relationship between the UCDAI and patient reported EQ-5D The UCDAI with or without endoscopy assessment demonstrated a good correlation with EQ-5D Endoscopy assessment may not link with the disease activity | |

| Kucharski et al[21] | 49 | Assessment of 9 endoscopic indices correlate well with (1) clinical indices; and (2) histological Geboes Index (22) The UCDAI showed strong correlations with all 9 endoscopic indices (the coefficient in a range of 0.712 to 0.790) The UCDAI showed the highest correlation amongst clinical activity indices with the Geoboes Index (the Spearman’s coefficient 0.478) Compared to UCEIS, the UCDAI is less correlated with the Geboes Index | |

| Reliability | Feagan et al[25] | 281 | The effect of centralized review of images on inter-observer variations Patients with UCDAI ≥ 2 were randomised to evaluate the efficacy of delayed mesalamine treatment (4.8 g/d for 10 wk) 31% of patients with UCDAI ≥ 2 enrolled in the RCT initially were considered ineligible by the central readers Inter-observer agreement amongst 7 central readers was good (interclass correlation coefficient: 0.78) |

Validity: The diagnostic and prognostic validity of an assessment tool is defined as evidence that variations in UC disease activity causally produce variations in the measurement outcomes. This must be demonstrated by qualitative assessment and evidence of indices measuring disease activity adequately and sufficient reflection of true disease. The development of these indices should be supported by a robust systematic review of literature. Statistical studies of agreement between the indices and disease activity should be assessed including sensitivity and specificity. Validity of the correlation between an index score and objective assessment score including clinical disease activity index scores or physician global assessment of severity should be measured. Although there are many indices have been proposed the degree of validity for these indices vary, and many indices are not fully validated. In this study, UCEIS and UCDAI, one of the best validated indices and most widely used indices in drug trials respectively, were studied for their evidence of validity.

The UCEIS is one of the well validated indices in many aspects. The authors have studied difficulties in standardisation of the disease activity indices and defining remission in systematic reviews as well as reviews of literature prior to the development of the UCEIS[29,30]. The authors attempted to develop an index that minimises this variation by validating variation in endoscopic assessment of disease activity, which was described in 2.1. The study also suggested remission might be defined as no obliteration of vascular pattern, no rectal bleeding and no erosion or ulceration, although this has not been fully validated.

Since the UCEIS was published in 2012, there are nine studies attempted to validate the UCEIS, of which four studies are focusing on validity.

Corte et al[18] validated whether the UCEIS predicts clinical outcomes of acute severe colitis. 98 Patients with the UCEIS score from 3 to 8 were included in this study. It showed when UCEIS ≥ 5, 33% (18/54) of acute colitis patients required colectomy 18/54 (33%) whereas only 9% (3/33) of patients with UCEIS ≤ 4 required surgical interventions. When the UCEIS score is above 7 at the time of admission, almost all patients required medical therapy more than hydrocortisone, such as infliximab or ciclosporin. It concluded that the higher UCEIS score is associated with higher requirement of rescue therapy, surgical intervention and readmission.

Fernandes et al[19] identified patients with poor response to optimal therapy with 108 patients who are defined as acute severe colitis based on the Truelove and Witts criteria (the score ≥ 2). All the patients received intravenous prednisolone 40-60 mg/d, methylprednisolone 60 mg or hydrocortisone 400 mg/d. Patients who had not responded to the initial therapy within 3 d received salvage therapy, and their UCEIS scores ranged from 2 to 8. The study also divided the UCEIS scoring system to segmental bowel - rectum and sigmoid, which demonstrated a strong correlation between higher UCEIS score and unfavourable outcomes especially the UCEIS-segmental score predicted refractoriness to steroid therapy. The UCEIS was significantly better at predicting clinical outcomes than the Mayo endoscopic sub-score.

Arai et al[20] attempted to foresee the prognosis of patients with UC who are in clinical remission. 285 patients who are in clinical remission (partial Mayo score of ≤ 1) were included in the study. The UCEIS score of these patients with clinical remission ranged from 0 to 5, of which 92% received a UCEIS score of 2 or 3. These scores are higher than a suggested score for clinical remission. The study demonstrated the recurrence risk is direct proportional to the UCEIS score - the recurrence rate of 5.0% for UCEIS = 0, 22.4% for UCEIS = 1, 27.0% for UCEIS = 2, 35.7% for UCEIS = 3, 75% for UCEIS = 4-5. The study also highlighted the absence of bleeding and mucosal damage being independent factors for clinical remission. The duration of recurrence was also significantly prolonged in patients with lower UCEIS score. The study presented validity of the UCEIS with its predictability of clinical outcomes. Furthermore, it suggests UCEIS ≤ 1 for clinical remission based on the direct correlation between the recurrence rate and the UCEIS, which showed sensitivity of 68% and specificity 57%.

Kucharski et al[21] assessed correlations between 9 endoscopic indices and 11 clinical activity indices. The author also assessed correlations between those endoscopic indices and the histological Geboes index[22]. Nine endoscopic indices used are Baron score[16], Powell-Tuck Score[31], Schroeder Score[32], UCDAI, Rachmilewitz Endoscopic Index[33], LÖtberg Score[34], Lemann Endoscopic Index[35], Feagan Score[36] and UCEIS. Eleven clinical activity indices are Truelove and Witts Severity Index[3], Powell-Tuck Index[31], Schroeder Score[32], UCDAI, Rachmilewitz Index[33], Lichtiger Index[37], Seo Score[38], Walmsley Index[39], Improvement Based on Individual Symptom Scores (IBOISS)[40], Feagan Score[36] and Montreal Classification of Severity of Ulcerative Colitis[41].

The correlations between clinical and endoscopic indices were evaluated using Spearman’s ranking correlation coefficient. The Rachmilewitz Index showed strong correlations with 5 clinical activity indices (UCDAI, Truelove and Witts, Schroeder Score, IBOISS and Feagan Index) with the correlation coefficient ranging in 0.710-0.788. The UCEIS also showed high correlations with the UCDAI, Schroeder Score, IBOISS and Feagan Index, the coefficient ranging from 0.722 to 0.761. When the correlations between clinical indices and the Geboes Index were assessed, all clinical indices showed low correlations, whereas all endoscopic indices showed better correlations with the histological Geboes Index. To evaluate correlations with endoscopic indices, all endoscopic indices were scored at four colonic segments right colon, transverse colon, left colon and rectum. The highest correlations were seen with the UCEIS at all four segments (the coefficient ranging from 0.434 to 0.629). The authors conclude that the UCEIS is the most effective endoscopic outcome measure instrument when considering correlations of both clinical and histological indices. In contrast, the UCDAI showed moderate correlations with rectal and transverse colonic segment with the Geboes Index with 0.651 and 0.534 respectively, though the correlations with other two segments were low with 0.428 for left colon and 0.459 for right colon.

Although the UCDAI has been widely used especially in multiple and large clinical trials, the study focused on validation of this index is much less compared to the UCEIS. The UCDAI was developed to assess the efficacy and safety of 5-aminosalicylic acid enema use for patients with UC[17]. The UCDAI claim to assess disease activity from four descriptors - stool frequency, rectal bleeding, mucosal appearance and physician’s global assessment of the disease. Although the description of each scoring system is simple to understand, it cannot avoid subjectivity without clear definition of each item. In particular, physician’s global assessment is far from being objective. Furthermore, the supposedly objective endoscopic assessment is scored based on severity of “friability”. Yet again, this friability without clear definition cannot avoid subjectivity, meaning it is exposed to greater inter- and intra-observer variability.

Higgins et al[27] defined objective end points in disease activity indices including UCDAI for remission and improvement in UC. This study was conducted on 66 patients with UC and their subjective dichotomous assessment of remission and regulatory remission were compared with the UCDAI. Regulatory remission was defined as (1) no more than grade I or II changes on a Feagan endoscopic score; and (2) absence of visible rectal bleeding in this study. It suggests the cut off point for clinical remission of the UCDAI is below 2.5, offering good statistical power - sensitivity and specificity is 0.82 and 0.89 for patient defined remission and 0.92 and 0.93 for regulatory remission. Patient-defined dichotomous end points may be over-simplification, however, as it is clinically significant outcomes that determines if therapies are perceived as beneficial by patients. Regardless of physicians’ objective assessment, patients with the disease are those that must agree with it in order to gain benefit in receiving therapies.

Poole et al[28] designed a new patient-reported disease assessment instrument, EuroQoI Five Dimensions Questionnaire (EQ-5D), for which the UCDAI was used to validate the instrument. Although validation of the UCDAI was not the aim of this study, the correlation between physician-rated and patient-rated instruments was elaborated. The study concluded that the abbreviated UCDAI (without endoscopic assessment component) and EQ-5D showed reasonable consistency when severity of the disease was measured in two randomised studies (PINCE[42] and PODIUM[43]). Goodness of fit was verified by the mean square error for mean predicted utility score. This showed patients in remission was 0.939, 0.944 and 0.940 mean utility units for estimated-PINCE, observed-PINCE and PODIUM.

Comparison of these two very different outcome measure instruments highlighted two incomparable benefits when they are chosen for clinical trials. The UCEIS is extensively validated and development of the index is based on robust studies, whereas the UCDAI is deigned based on expert opinion on the disease. However, the UCDAI is more widely used in clinical trials. This makes the choice of an index for future clinical trial studies more difficult when the clinical benefit was considered. In this systematic review, only two indices are compared. With current inconsistent use of measurement instruments and non-standardised definition of remission, the choice is almost impossible.

Responsiveness: Responsiveness is assessed in this systematic review as the ability to detect changes after a treatment that has known efficacy.

Ikeya et al[23] investigated true evaluation of UC severity and outcome after Tacrolimus remission induction therapy using the UCEIS as well as Mayo endoscopic subscore (Mayo ES) with 41 patients who are known to have moderate to severe disease.

In this study, clinical remission was defined as clinical activity index (CAI) ≤ 4 and a reduction of CAI score more than 4 was defined as clinical response. On the contrary, an increase of CAI score more than 4 was defined as relapse.

After 12 wk from the treatment, 31 patients (75.6%) successfully achieved clinical remission [defined as clinical activity index (CAI) ≤ 4] and 3 patients did not respond. Overall the UCEIS and Mayo ES showed close correlations, however, when the Mayo ES was 3, there was prominent discrepancy between the two indices. The UCEIS score equivalent to Mayo ES 3 ranged from 5 to 8 pre-treatments and 3 to 7 post-treatments. This was believed to be due to a lack of ability to distinguish characteristics of ulcers, vascular patterns or bleeding with the Mayo ES. For instance, ulcers and erosions often become smaller and shallower in the early phases of mucosal healing. Since the Mayo ES does not distinguish the size and depth of ulcers, it tends to stay with the same score, meaning the Mayo ES score is 3 for all types of ulcers. Furthermore, the Mayo ES combine all those macroscopic findings of ulcers, vascular pattern and bleeding into four different overall grades. This means if there are ulcerations of any shape, the Mayo ES score becomes 3, even if vascular pattern disturbance is resolved.

The study also demonstrated significantly better relapse-free and colectomy-free rates when the UCEIS score was improved by more than 3. In addition, improvement by a UCEIS score of more than 3 was strongly associated with achieving clinical remission group (23 out of 41 patients).

Menasci et al[24] evaluated to see whether the global score of the sum of 5 colonic segments (rectum, sigmoid, descending, transverse, and ascending colon), abbreviated as tU score, would alter the outcome score when it is compared with the regular method of UCEIS scoring, which is to score the most inflamed colonic segment. The two scores showed a good correlation with Spearman’s r = 0.86 and P value less than 0.0001 for less severe disease UCEIS ≤ 5. However, correlation is substantially decreased for severe disease (UCEIS > 5) with Spearman’s r = 0.48 and P < 0.01. Moreover, when these two scoring methods were applied to assess patients with a flare-up at 1 year, tU score was more sensitive than the regular UCEIS score with area under ROC curve = 0.688 ± 0.06 vs 0.60 ± 0.07 and P < 0.01. The tU score was also significantly higher when patients with and without a flare-up at 1 year were assessed, whereas the regular UCEIS score did not differ (25.3 ± 8.2 vs 20.1 ± 6, P < 0.005). This concluded that the evaluation of disease by full colonoscopy with multiple segments may provide the more accurate method to evaluate disease activity.

Overall, the study concluded that the UCEIS confirmed better responsiveness than the UCDAI, and it is superior to describe accurate endoscopic findings in patients with severe UC. This responsiveness can be crucial in clinical trials since duration of primary endpoints in many clinical trials is approximately 12 wk[44]. Thus, indices that allow to capture small but vital improvement that reflects on disease outcome is essential to clinical trials.

Reliability: Despite mucosal healing becoming the goal for management for UC, the most critical limitation of endoscopic assessment is its inherent intra- and inter-observer variations[6,45-47]. Reliability is evaluated with inter- and intra-observer reliability as well as internal consistency. The leading author of the UCEIS led another study to investigate reliability in different aspects.

The first study published in 2013 investigated intra- and inter-observation reliability[15]. Twenty-five readers from 14 countries were recruited in this study, who evaluated 28 videos. To quantify intra-observer reliability, 4 duplicated videos were included. For inter-observer reliability, all readers were trained to ensure consistent understanding and use of the scoring system. Internal consistency was measured using the Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, which was 0.863 for the overall UCEIS - bleeding 0.80, vascular pattern 0.83, and ulcers and erosions 0.79.

The study found that the intra and inter-observer reliability ratios for the UCEIS were 0.96 and 0.88 respectively. Intra-observer agreement static was calculated with kappa, which was 0.72, with individual descriptors ranging from 0.47 (for bleeding) to 0.87 (for vascular pattern). Inter-observer agreement statistic was slightly lower at 0.50, with individual descriptors ranging from 0.48 (bleeding) to 0.54 (vascular pattern). Additionally, these observer reliabilities were compared with readers who were given clinical information at the time of the video readings, which determined no apparent bias by clinical information.

To evaluate the impact of clinical information on UCEIS scores, the author also undertook another study in 2015[26]. The study invited 40 readers from various countries who were experienced with endoscopic assessment. Each reader was divided into two groups (with and without clinical information) and conducted evaluation of a random 28 from 44 videos, which had not been used in the previous study. Furthermore, 4 videos included misleading information in order to ensure disparity between endoscopic assessment and clinical information.

This study showed there is no impact of clinical information on mean UCEIS scores. They were almost identical whether readers had knowledge of patient’s clinical information and the median SD was 0.94 for blinded and 0.93 for unblinded. The SD was low for videos with severe disease.

Intra- and inter-observer agreement of the blinded and unblinded readers was also evaluated. Intra-observer agreements for bleeding and vascular pattern were very similar for the two groups, whereas that for erosions and ulcers just reached to statistical significance with kappa of 0.47 for blinded and 0.74 for unblinded.

The study also extended to compare the UCEIS with other indices and patient-reported symptom scoring systems. The full Mayo Clinic Score (MC)[32], partial MC (excluding endoscopic subscore)[48], patient-reported stool frequency and rectal bleeding subscore, patient functional assessment score and Feagan score were compared with the UCEIS as well as Feagan Score[36]. This showed the UCEIS is significantly superior to the Feagan Score including patient-reported symptom subscore. This implies that the UCEIS alone may be sufficient for outcome measurement in clinical trials.

The only inter-observer and central reader variations study on UCDAI also referred to UCEIS[25]. The authors investigated the role of central readers to minimise inter-observer variations, which may contribute to false responses to placebo in UC trials. They conducted a 10-wk randomised double-blinded placebo-controlled study on patients with UC who scored UCDAI ≥ 2.

Three hundreds and forty-three patients, who were initially assessed by site investigators, were enrolled to the randomised clinical trials. Clinical remission (UCDAI, stool frequency and bleeding scores of 0) was achieved by 30.0% of patients treated with mesalamine and 20.6% of those with placebo. However, when those 343 were re-assessed by 7 central-readers, 31% of those patients were in fact ineligible as they scored lower than 2. Furthermore, this altered the remission rate to 29.0% and 13.8% in the mesalamine and placebo groups respectively. In conclusion, this study suggests robust methodology for future clinical trials in UC to avoid misleading results.

The authors also extended the study to quantify the inter-observer variation amongst 7 central readers using UCDAI, UCEIS, Feagan score, visual analogue scale. Of those indices, UCEIS demonstrated the highest interclass correlation coefficient with 0.83 and UCDAI was 0.79. The authors concluded that this might be attributed to no friability assessment in UCEIS, which is the commonest source of disagreement between central and site readers in this study.

Definition of remission: Remission rates can vary by more than two-fold depending on the definition of remission used for data analysis[49]. In addition to uncertainty about standardisation of disease activity measurement, disease remission has also never been conclusively defined or validated. Defining disease remission should be the fundamental starting point of studying therapeutic efficacy and disease monitoring, before standardising how to measure disease activity.

Definitions of remission in UC vary depending on users, settings and the purpose of monitoring the disease activity. The definition of remission used in clinical practice and by the patient is often different from that used in clinical trials. Remission, clinical remission, complete remission, partial remission, clinical response, mucosal healing or remission, corticosteroid-free remission, registration remission are frequently employed terms used in clinical practice by healthcare professionals and patients, although these terms are used interchangeably and variably without strict definition, including in clinical trials.

Table 5 is a summary of definitions of remissions in UC defined by large regulatory bodies and guidelines. All guidelines mention remission to manage disease, however, few guidelines explicitly define remission. The American College of Gastroenterology is no exception, though it controversially states that, “practical therapeutic end point, endoscopic demonstration of mucosal healing is not usually necessary for a patient who achieves clinical remission”. The FDA recommends a primary endpoint of clinical remission, and clinical remission is defined as follows[5]: Rectal Bleeding subscore = 0: (1) Stool Frequency subscore = 0 (or stool frequency subscore 1 is considered if at least one point improvement in Stool Frequency subscore from baseline); and (2) Endoscopy subscore 0 on UCDAI.

| Guidelines | Definition |

| FDA[5] | Clinical remission Mayo score of ≤ 2 with no individual subscore > 1 Rectal Bleeding subscore = 0 Stool Frequency subscore = 0 (at least one point decrease in Stool Frequency subscore from baseline and achieved 1 is considered) Endoscopy subscore = (Mayo score: 0 or 1, UCDAI = 0) Clinical response Reduction in Mayo score ≥ 3 and ≥ 30% from baseline with Rectal Bleeding subscore ≤ 1 Corticosteroid-free remission Clinical remission in patients using oral corticosteroids at baseline who have discontinued them and are in clinical remission at the end of the study |

| World Gastroenterology Organisation | Clinical remission UCDAI ≤ 2 (2010 World Gastroenterology Organisation Practice Guideline)[50] Corticosteroid-free remission Decreasing the frequency and severity of recurrence and reliance on corticosteroids |

| International Organisation for the Study of IBD | End points = induction of remission = mucosal healing[12] The absence of friability, blood, erosions and ulcers in all visible segments No mention of clinical symptoms |

| American College of Gastroenterology | No clear definition[51] |

| British Society of Gastroenterology | No clear definition[52] |

| European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation | Remission[53] A complete resolution of symptoms and endoscopic mucosal healing Not been a fully validated definition of remission Suggest the best way forward is a combination of Stool Frequency ≤ 3 No rectal bleeding Normal or quiescence mucosa at endoscopy Clinical response Clinical and endoscopic response depending on the activity index Generally, a decrease in the activity index > 30% plus a decrease in the rectal bleeding and endoscopic subscores |

It also describes mucosal healing should not be supported from macroscopic appearance of the mucosa through endoscopy. However, the FDA further describes that there are no criteria for histological assessment of mucosal healing due to a lack of validated gold standard histological scoring systems.

The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) more realistically states in their guidelines for patients in UC that there is no fully validated definition of remission.

How indices are used in clinical trials and defining remission endpoints: Since there is no gold-standard outcome measurement instruments in UC, many clinical trials have employed instruments depending on its application. Classic disease activity measurement instruments have been recently challenged by the FDA because of the significant effect of their subjective components affecting reproducibility. Even the traditionally promoted indices used by the FDA (Mayo Score and UCDAI) contain physician global assessment, which is highly sensitive to bias. The FDA suggests the primary endpoint should be achieved by endoscopic as well as clinical outcome, however, the difficulty in this is that these symptoms do not necessarily occur simultaneously with symptom control, especially where stool frequency and abdominal pain are considered. Nevertheless, these symptoms affect patients’ quality of life. There are therefore further hurdles to overcome before standardisation of endpoint definition in UC[44].

In this systematic review, remission endpoints were investigated by studying the application of the UCEIS and UCDAI in clinical research and therapeutic trials (Tables 6 and 7). There are only three clinical research identified which applied the UCEIS for disease outcome measure and defined remission. Furthermore, only one randomised clinical trial has chosen the index for its outcome measurement instrument so far[54].

| Ref. | Year | Type of study | Drug/subject of study | Entry criteria | Primary endpoint | Secondary endpoint | Remission/clinical improvement | Length of study |

| Hartman et al[54] | 2016 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | AVX-470, oral | 36 patients with Mayo score 5-12 and Mayo ES ≥ 2 | Not set, but implies clinical response at week 4 | Not set | Remission was not defined. Clinical response Mayo reduction ≥ 3 | 4 wk |

| Lin et al[55] | 2015 | Prospective, multi-centre study | Faecal calprotectin | 52 patients with UC | N/A | N/A | Endoscopic remission: UCEIS < 3 | N/A |

| Magro et al[56] ACERTIVE study | 2016 | Cross-sectional multi-centre study | Faecal calprotectin/ lipocalin | 371 patients Mayo partial score < 2, montreal classification < 2 | Remission: UCEIS ≤ 1 Mucosal healing: Mayo ES = 0 |

| Ref. | Year | Drug | Entry criteria | Primary endpoint | Secondary endpoint | Remission/clinical improvement | Length of study |

| Randomised clinical trials - to induce remission | |||||||

| Mesalazine (5-ASA) | |||||||

| Marteau etal[58] | 2005 | Pentasa (PR + PO vs PO alone) | UCDAI: 3-8 | Remission at week 4 | Remission rate at week 8 Improvement at week 4 and 8 | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 Clinical improvement: A decrease of UCDAI ≥ 2 | 8 wk |

| D’Haens etal[59] | 2006 | SPD476 - MMX mesalazine | UCDAI: 4-10 + endoscopic score ≥1 PGA score ≤ 2 | Remission | Change in UCDAI, FS, histology at week 8 Change in symptoms | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 (with RB 0, SF ≤ 1 ) at week 8 | 8 wk |

| Sandborn etal[60] | 2007 | MMX Multi Matrix System mesalazine | UCDAI: 4-10 + endoscopic score ≥1 PGA score ≤ 2 | Clinical/endoscopic remission at 8 wk | Proportion of clinical improvement Proportion of patients as treatment failure Change in: RB, SF, FS | Clinical remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 Endoscopic remission: UCDAI endoscopic subscore ≤ 1 Clinical improvement: A decrease of UCDAI ≥ 3 Treatment failure: Unchanged or worsened UCDAI | 8 wk |

| Lichtenstein et al[61] | 2007 | SPD476 - MMX mesalazine OD vs BD | UCDAI: 4-10 | Clinical and endoscopic remission at week 8 | Comparison of remission rate at week 8 | Clinical remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 with RB/SF/EI = 0 | 8 wk |

| Kamm et al[62,63] MEZAVANT study | 2007 2009 | MEZAVANT MMX Mesalamine | Mild - mod UC: UCDAI 4-10 + endoscopic subscore ≥ 1, PGA ≤ 2 | Clinical + Endoscopic remission at week 8 | Clinical remission Clinical improvement Change in UCDAI | Clinical + endoscopic remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 + subscore RB/SF = 0, No mucosal friability + a ≥ 1 reduction in EI Clinical improvement: Decrease in UCDAI ≥ 3 | 8 wk |

| Ito et al[64] | 2010 | Asacol vs PentasaTime-dependent vs pH dependent Mesalamine | UCDAI: 3-8 and blood stool score ≥ 1 | To demonstrate Asacol over Pentasa AND the decrease in UCDAI | Macroscopic changes | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 2 and no blood diarrhoea Clinical improvement: UCDAI decreased by ≥ 2 | 8 wk |

| Hiwatashi etal[65] | 2010 | Mesalazine - dose study | UCDAI: 6-8 | Change in UCDAI at week 8 | Remission, improvement, efficacy | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 Efficacy: Decrease of UCDAI ≥ 2 | 8 wk |

| Flourié et al[66] MOTUS study | 2013 | Mesalazine, Pentasa OD or BD in total of 4 g/d | UCDAI: 3-8 | UCDAI ≤ 1 after 8 wk | Complete remission (UCDAI = 0) at 8 wk UCDAI decreased by ≥ 2 at 8 wk Clinical remission at week 4, 8, 12 Mucosal healing at 8 wk | Complete remission: UCDAI = 0 Endoscopic remission: UCDAI endoscopic subscore: 0 or 1 Clinical remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 | 12 wk |

| Probert et al[42] PINCE study | 2013 | Mesalazine (pentasa) enema | UCDAI: 3-8 | Remission rate (UCDAI < 2) at 4 wk | Remission rate at 8 wk, improvement at week 2, 4 and 8 Time to cessation of RB QoL (EQ-5D) | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 Clinical improvement: UCDAI decreased by ≥ 2 | 8 wk |

| Sun et al[67] | 2016 | Mesalazine (modified-release vs enteric-coated tablets) | UCDAI: 3-8 + bloody stool score > 1 | The decrease in UCDAI | Remission rate Efficacy rate | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 2 + bloody stool 0 Clinical improvement: A decrease of UCDAI ≥ 2 | 8 wk |

| Suzuki etal[68] | 2016 | pH dependent release mesalamine, asacol dose | UCDAI: 6 - 10 Rectal bleeding score ≥ 1 | Decrease in UCDAI | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 2 Rectal bleeding score: 0 Improvement UCDAI decreased by ≥ 2 | 8 wk | |

| Thiazole compounds | |||||||

| Mantzaris etal[69] | 2004 | Azathioprine alone (2.2 mg/kg) vs combination with olsalazine (0.5 g TID) | Steroid-dependent remission | Relapse rate | Time to relapse Time to discontinuation Severity of relapse | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 Relapse: New symptoms + UCDAI > 3 | 2 yr |

| Schreiber etal[70] | 2007 | Tetomilast - Thiazole compound | UCDAI: 4-11 | Clinical improvement: UCDAI decreased by ≥ 3 at 8 wk | Remission Clinical improvement at week 4 IBDQ-32 score Proportion of pts with improved Flexible Sigmoidscopy score Time to clinical improvement Time to remission | Clinical improvement: UCDAI decreased by ≥ 3 Remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 | 8 wk |

| Steroids | |||||||

| Travis et al[71] CORE II study | 2012 | Budesonide MMX | UCDAI: 4-10 | Clinical/endoscopic remission at week 8 | Clinical improvement Endoscopic improvement at week 8 | Clinical/endoscopic Remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 + RB/SF/EI = 0 Clinical improvement: A decrease of UCDAI ≥ 3 Endoscopic improvement: A decrease of EI ≥ 1 | 8 wk |

| Probiotics | |||||||

| Vernia etal[72] | 2000 | Sodium Butyrate | Mild-moderate UC | Remission or marked improvement | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 2 Positive response: Decrease of UCDAI ≥ 2 | 6 wk | |

| Mahmood etal[73] | 2005 | Human recombinant trefoil factor 3 enema | UCDAI: >3 | Remission at week 2 | Clinical significant improvement in clinical and histological scores at 2 and 4 wk | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 without RB Clinical improvement: A decrease of UCDAI >3 | 4 wk |

| Lichtenstein et al[74] | 2007 | Bowman-Birk inhibitor concentrate - soy extract with high protease inhibitor activity | UCDAI: 4-10 | Remission at week 8 | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 1 + no RB or SF Clinical improvement: UCDAI decrease ≥ 1 | ||

| Tursi et al[75] | 2009 | VSL #3 (probiotic) | UCDAI 3-8, endoscopic subscore ≥ 3 | Decrease in UCDAI of ≥ 50% | Activity of relapsing UC Remission Improvement Change in objective and subjective symptoms | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 2 | 8 wk |

| Sood et al[76] | 2009 | VSL #3 probiotic | UCDAI 3-9 with endoscopic subscore ≥ 2 | Clinical improvement at week 6 | Clinical remission | Clinical remission: UCDAI ≤ 2 Clinical improvement: A decrease UCDAI by 50% | 12 wk |

| Tamaki etal[77] | 2016 | Bifidobacterium longum 536 (probiotic) | UCDAI 3-9 | Change in UCDAI | Remission Improvement of Objective and subjective symptoms Endoscopic improvement in Mayo subscore | Remission: UCDAI ≤ 2 | 8 wk |

| Helminth therapy Garg etal[78] | 2014 | Helminth Trichuris suis ova | UCDAI of ≥ 4 | Clinical improvement | Clinical remission | Clinical improvement: Decrease in the UCDAI of ≥ 4 Clinical remission: UCDAI of ≤ 2 | 12 wk |

| Nicotine therapy | |||||||

| Ingram etal[79] | 2005 | Nicotine enema 6 mg/d | Confirmed UC with inflamed mucosa grade > 2 | Clinical remission | Improvement in the UCDAI | Clinical remission: UCDAI EI ≤ 1 and No RB for 1 wk | 6 wk |

| Randomised clinical trials - to maintain remission | |||||||

| Lichtenstein et al[80-82] and Zakko etal[83] | 2010 2012 2015 2016 | Mesalamine granules 1.5 g/d, OD | Previously achieved remission with steroids for > 1 mo and < 12 mo | Percentage of patients relapse-free at 6 mo | Mean changes from baseline at month 6 | Relapse: UCDAI RB ≥ 1 and EI ≥ 2 Remission: UCDAI RB = 0, EI < 2 | 6 mo |

| Bokemeyer et al[43] and Dignass etal[84] | 2009 2011 | Mesalazine, Pentasa OD or BD in total of 2 g/d | Clinical remission: UCDAI < 2 | To demonstrate OD is not inferior to BD | Time to relapse between 2 groups UC-DAI total and subscores between 2 groups | Remain in remission UCDAI ≤ 2 | 12 mo |

The trial was the first-in-human trial of AVX-470, which is a bovine-derived, orally-administered, anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) antibody, that works to intestinal mucosal tissue with minimal systematic effects. TNF is upregulated in the colonic mucosa in UC and believed to play a pathological role by loss of mucosal barrier integrity[57]. AVX-470 reduces levels of TNF protein in mice models, thus correcting immune dysregulation. In this study, the UCEIS was used to assess endoscopic response to treatment along with the total Mayo score and sub-scores.

This study successfully correlates between UCEIS scores and TNF immunohistochemistry scores at baseline. Further, it found that TNF staining was significantly reduced in proximal and distal segments of bowel, whereas the UCEIS changes were more apparent in proximal segments than distal ones. Although the study described achieving clinical remission, this was never defined.

The UCEIS was used for endoscopic assessment in a prospective study to quantify faecal calprotectin in patients with UC[55]. The authors used Quantum Blue Calprotectin High Range Rapid Test (Buhlmann laboratories AG, Schonenbuch, Switzerland) for faecal calprotectin measurement tools in this study. Interestingly, the authors defined endoscopic remission when the UCEIS < 3. They also concluded that faecal calprotectin and CRP were both well correlated with the UCEIS (the Spearman correlation coefficient is 0.696 and 0.581 respectively). Moreover, they concluded that when a cut-off faecal calprotectin of 191 μg/g is set, this could predict endoscopic remission and mucosal remission (UCEIS < 3) with 88% sensitivity and 75% specificity. However, when UCEIS < 1 clinical remission proposed by other authors[14,23] is applied, faecal calprotectin would be lower than 191 μg/g. This could lead to underestimate patients who should be treated.

The largest patient population study that used the UCEIS is a cross-sectional, multi-centre study, ACERTIVE study[56]. The aim of this study was to evaluate potential applications of biomarkers (faecal calprotectin and neutrophil gelatinase B-associated lipocalin) as disease activity measuring instrument in patients with asymptomatic UC. The UCEIS and Geboes index[22] were applied for macroscopic and microscopic assessment respectively. Nine percent of the asymptomatic patients had active disease with UCEIS > 2. Twenty-one percent of the asymptomatic patients presented with Geboes index > 3. One point fifteen percent and 5% of the patients presented with focal and diffuse basal plasmacytosis, respectively. Patients with asymptomatic disease indeed showed presence of macroscopic as well as microscopic disease. Furthermore, 50% of patients who scored a UCEIS < 2 and 15% of patients who were considered to have achieved mucosal healing (Mayo ES = 0) had diffuse basal plasmacytosis. These results support the previous published notion that macroscopic findings are not sufficient to define remission or endpoint[9].

Both biomarkers predicted mucosal healing as well as histological remission with satisfactory probability of 75%-93%. The authors proposed a cut-off figures of 150-250 μg/g for faecal calprotectin and 12 μg/g for lipocalin. This range of cut-off level for faecal calprotectin is due to the application of two faecal calprotectin measurement tools (Quantum Blue Calprotectin High Range Rapid Test and Automated Fluroimmunoassay-EliA Test) from stool samples. Although this proposed cut-off point for faecal calprotectin for clinical remission is a similar value with the Taiwan group[55], the defined remission show variance as the Taiwan group set UCEIS < 3 for remission whereas ACERTIVE study used UCEIS ≤ 1. Although it is only one score difference, this can be of significance for disease outcome. As Arai et al[20] concluded, the recurrence rate was directly proportional to the UCEIS score. The recurrence rate for UCEIS 1 disease is 22.4%, whereas UCEIS 2 disease increases to 27.0%. As the authors state validation of the proposed cut-off values is required before introducing them in clinical setting. Moreover, caution should be applied when introducing biomarkers especially when their intention is to replace endoscopic assessment.

Table 6 shows the summary of the randomised clinical trials that utilised the UCDAI for disease activity assessment, defining remission and endpoints. The studies were divided into introduction and maintenance of disease remission.

Most of the studies investigated the efficacy of introducing remission set clinical remission as UCDAI ≤ 1, however some studies defined as UCDAI ≤ 2 for remission. It appears that many studies have taken advantage of defining their own remission, clinical response and endpoints with the UCDAI as it is not clearly defined in previous guidelines. The studies with probiotics appear to choose higher remission cut-off point, which could interpret that it is undemanding to achieve clinical remission so that it would satisfy requirements of regulatory bodies such as the FDA. The previous validation study suggested UCDAI score < 2.5 for clinical remission[65], meaning UCDAI ≤ 2 is still within the range of remission.

Another point to note is that many studies have their own additional criteria with a specific patient-reported symptom scoring system to measure rectal bleeding and stool frequency to define remission or clinical response. This is likely attributed to the guideline published by the FDA, which encourages to assess patient-reported outcome measurement on rectal bleeding and stool frequency in addition to the macroscopic assessment with endoscopy as an endpoint for clinical trials. This is also reflected on their definition of clinical remission on Table 5.

If a more stringent primary endpoint is enforced the clinical utility of therapeutics may be harder to demonstrate, potentially limiting the number of agents available in the marketplace. Furthermore, drug development for UC faces bigger challenge due to the unknown natural history of UC, unpredictable relapse and remission patterns as well as response to medications with known efficacy. If the stringent remission and endpoint was forced by regulatory bodies, the pharmaceutical industry may choose drugs that have cheaper development cost.

Although the FDA supports the use of UCDAI for measuring primary endpoints, UCDAI has limitations. As it is highlighted in the previous section, one of the weakness is a lack of validation and vulnerability to observer bias. Adding inconsistent definition of remission and endpoint for each clinical trial hinders providing optimal management to patients with the disease.

Homogeneity of the clinical trials in UC has been discussed amongst experts for decades. Despite a desire for a single gold-standard disease activity index, the number of indices has been steadily increasing. Disease remission is yet to be fully defined, thus trial outcomes vary and limit the utility of these studies depending on the purpose of its clinical use. Most trials chose individual endpoints which are not necessarily clinically pertinent. Clinicians, on the other hand are constantly negotiating with patients to provide the best possible management for this chronic condition, regardless of an index score. This variation makes the comparison amongst clinical trials extremely difficult, hindering drug development.

So far, many review studies summarised and evaluated currently available indices on different assessments. The majority of these studies highlighted the wide variation of endpoints by different indices and emphasised the importance of having a gold-standard index to assess the efficacy of the interventions. This has led to development of more indices rather than choosing a gold-standard index, adding more choices and fuelling confusion amongst researchers and clinicians. This systematic review proposes to emphasise on a universal consensus on UC remission before developing any more indices. Futher more this systematic review would assist scientists and clinicians to have a better understanding of confusing definitions and disease activity indices that have been used interchangeably.

This systematic review was conducted to evaluate the definition and evidence for remission endpoints in ulcerative colitis from the point of view of two particular indices. The UCDAI has been widely used in clinical studies compared to the UCEIS. Although the UCEIS has been extensively validated, only one randomised clinical trial has employed the UCEIS as their outcome measurement instrument of date. The reason may be threefold. Firstly, other traditional disease activity measurement instruments have been widely used in previous clinical trials, making comparison with those trials more straightforward, although less robust. Secondary, if clinical trials were conducted for drug development, they would more likely choose the disease activity indices as recommended by regulatory bodies such as the FDA or equivalent. Finally, the UCEIS was recently developed thus there is no surprise that the number of clinical trials using this scoring system is still low.

The other two studies that used the UCEIS are not randomised clinical trials, though they demonstrated how multiple definitions of remission used in the evaluation of biomarker, calprotectin, to monitor disease activity could alter the outcomes. Without a universal definition of remission, researchers can freely define the UCEIS score for a remission endpoint, making evaluation of calprotectin use in clinical practice very difficult.

Furthermore, regulatory bodies such as the FDA recommend measuring endpoints in terms of clinical remission with particular indices, although they still do not convey the ideal length of clinical trial to achieve a primary endpoint or the duration of clinical remission before relapsing. This diversity of clinical protocols was also emphasised in this systematic review.

One of the criticisms for traditional outcome measurement instruments has been insufficient validation. The UCEIS has designed to overcome from this problem and to take a step forward for establishing a gold standard outcome measurement instrument. Yet, this systematic review highlighted that validation is not necessarily an issue for employing an outcome measurement instrument for clinical trials. Although we focused on developing new ideal indices, a new index may not be a solution to establish a gold standard outcome measurement instrument.

A lack of understanding in aetiology and natural history of ulcerative colitis may contribute to this confusion. In order to untangle this confusion, we recommend that an international consensus of remission should be sought as a matter of urgency before establishing a gold standard outcome measurement. Once a universal consensus for remission is reached and defined, establishing a gold-standard index, which can measure true symptoms and is transferable and meaningful to clinical practice, can be determined. That would lead to standardisation of clinical trial protocols for advancing patient care.

The current target of disease remission endoscopically is mucosal healing although it has not been fully validated or no standardised definition of mucosal healing. Yet, this appears to be the goal for many clinical practice as well as drug trials. The recent draft guideline released by the FDA states the ideal primary efficacy assessment instrument in clinical trials should consist of (1) a signs and symptoms assessment scale - best measured by a patient-reported outcome instrument. If not, an observer-reported outcome instrument; and (2) an endoscopic and histological assessment scale. Thus, endoscopic assessment tools with comprehensive clinical symptom assessment components that come from patients would be a reasonable choice to argue remission and endpoints employed in clinical trials.

The authors believe this has been mentioned everywhere in the paper that definition of ulcerative colitis endpoint has been introducing ambiguity especially when different clinical trial studies are compared. The authors also mentioned in the summary that a lack of understanding in aetiology and disease natural history may contribute to this confusion, which needs to be addressed in the future research.

The authors added to emphasize the differences from other similar studies.

The authors added “This systematic review would assist scientists and clinicians to have a better understanding of confusing definitions and disease activity indices that have been used interchangeably”.

This is a comprehensive review of remission endpoints in ulcerative colitis, the paper is well written and is very useful for both clinical practice and teaching purposes.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gurkan A, Lakatos P, Ribaldone DG S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2199] [Cited by in RCA: 2445] [Article Influence: 305.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Andrew RE, Messaris E. Update on medical and surgical options for patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis: What is new? World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:598-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2:1041-1048. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Walsh AJ, Bryant RV, Travis SP. Current best practice for disease activity assessment in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:567-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Samaan MA, Mosli MH, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, D' Haens GR, Dubcenco E, Baker KA, Levesque BG. A systematic review of the measurement of endoscopic healing in ulcerative colitis clinical trials: recommendations and implications for future research. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1465-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lichtenstein GR, Rutgeerts P. Importance of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:338-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Popp C, Stăniceanu F, Micu G, Nichita L, Cioplea M, Mateescu RB, Voiosu T, Sticlaru L. Evaluation of histologic features with potential prognostic value in ulcerative colitis. Rom J Intern Med. 2014;52:256-262. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bryant RV, Winer S, Travis SP, Riddell RH. Systematic review: histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Is 'complete' remission the new treatment paradigm? An IOIBD initiative. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1582-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gray JR, Leung E, Scales J. Treatment of ulcerative colitis from the patient's perspective: a survey of preferences and satisfaction with therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:1114-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Van Deen WK, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Parekh NK, Kane E, Zand A, DiNicola CA, Hall L, Inserra EK, Choi JM, Ha CY. Development and Validation of an Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Monitoring Index for Use With Mobile Health Technologies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1742-1750.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Geboes K, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Lémann M, Marteau P, Rutgeerts P, Schölmerich J. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 788] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61:1619-1635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 676] [Cited by in RCA: 654] [Article Influence: 50.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Travis SP, Schnell D, Krzeski P, Abreu MT, Altman DG, Colombel JF, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lémann M, Lichtenstein GR. Developing an instrument to assess the endoscopic severity of ulcerative colitis: the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS). Gut. 2012;61:535-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Travis SP, Schnell D, Krzeski P, Abreu MT, Altman DG, Colombel JF, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, Marteau PR. Reliability and initial validation of the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:987-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Baron JH, Connell AM, Lennard-Jones JE. VariationA between observers in describing mucosal appearances in proctocolitis. Br Med J. 1964;1:89-92. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Sutherland LR, Martin F, Greer S, Robinson M, Greenberger N, Saibil F, Martin T, Sparr J, Prokipchuk E, Borgen L. 5-Aminosalicylic acid enema in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis, proctosigmoiditis, and proctitis. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1894-1898. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Corte C, Fernandopulle N, Catuneanu AM, Burger D, Cesarini M, White L, Keshav S, Travis S. Association between the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) and outcomes in acute severe ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:376-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fernandes SR, Santos P, Miguel Moura C, Marques da Costa P, Carvalho JR, Isabel Valente A, Baldaia C, Rita Gonçalves A, Moura Santos P, Araújo-Correia L. The use of a segmental endoscopic score may improve the prediction of clinical outcomes in acute severe ulcerative colitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:697-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Arai M, Naganuma M, Sugimoto S, Kiyohara H, Ono K, Mori K, Saigusa K, Nanki K, Mutaguchi M, Mizuno S. The Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity is Useful to Predict Medium- to Long-Term Prognosis in Ulcerative Colitis Patients with Clinical Remission. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1303-1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kucharski M, Karczewski J, Mańkowska-Wierzbicka D, Karmelita-Katulska K, Grzymisławski M, Kaczmarek E, Iwanik K, Rzymski P, Swora-Cwynar E, Linke K. Applicability of endoscopic indices in the determination of disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:722-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Geboes K, Riddell R, Ost A, Jensfelt B, Persson T, Löfberg R. A reproducible grading scale for histological assessment of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2000;47:404-409. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Ikeya K, Hanai H, Sugimoto K, Osawa S, Kawasaki S, Iida T, Maruyama Y, Watanabe F. The Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity More Accurately Reflects Clinical Outcomes and Long-term Prognosis than the Mayo Endoscopic Score. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:286-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Menasci F, Pagnini C, Di Giulio E. Disease Extension Matters in Endoscopic Scores: UCEIS Calculated as a Sum of the Single Colonic Segments Performed Better than Regular UCEIS in Outpatients with Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:692-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D'Haens G, Pola S, McDonald JW, Rutgeerts P, Munkholm P, Mittmann U, King D, Wong CJ. The role of centralized reading of endoscopy in a randomized controlled trial of mesalamine for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:149-157.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |