Published online Feb 26, 2017. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v5.i1.1

Peer-review started: July 25, 2016

First decision: September 29, 2016

Revised: October 15, 2016

Accepted: December 13, 2016

Article in press: December 14, 2016

Published online: February 26, 2017

Processing time: 220 Days and 11.5 Hours

To investigate by meta-analytic study and systematic review, advantages of colonic stent placement in comparison with emergency surgery.

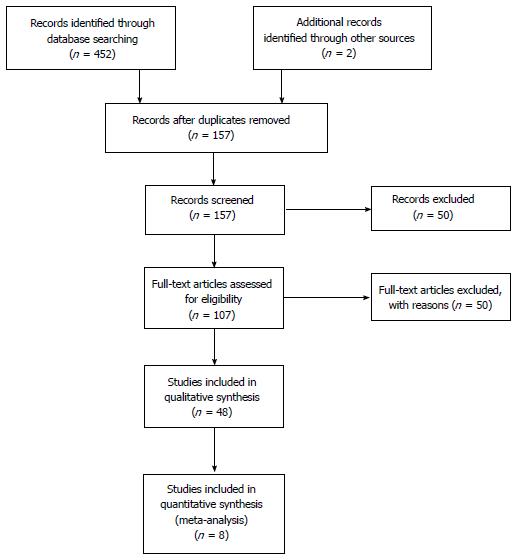

We conducted an extensive literature search by PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase and the Cochrane Libraries. We searched for all the papers in English published till February 2016, by applying combinations of the following terms: Obstructive colon cancer, colon cancer in emergency, colorectal stenting, emergency surgery for colorectal cancer, guidelines for obstructive colorectal cancer, stenting vs emergency surgery in the treatment of obstructive colorectal cancer, self-expanding metallic stents, stenting as bridge to surgery. The study was designed following the Prisma Statement. By our search, we identified 452 studies, and 57 potentially relevant studies in full-text were reviewed by 2 investigators; ultimately, 9 randomized controlled trials were considered for meta-analysis and all the others were considered for systematic review.

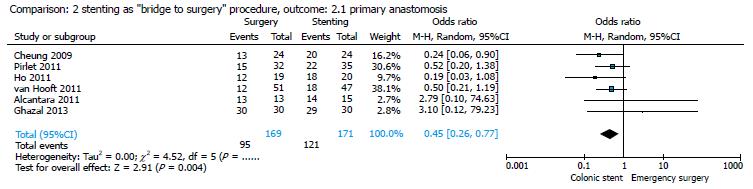

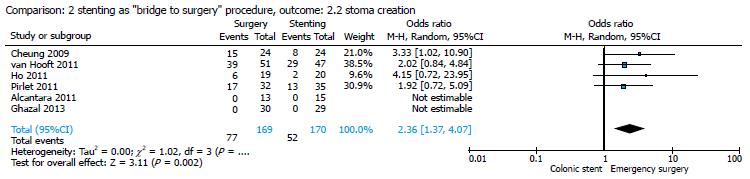

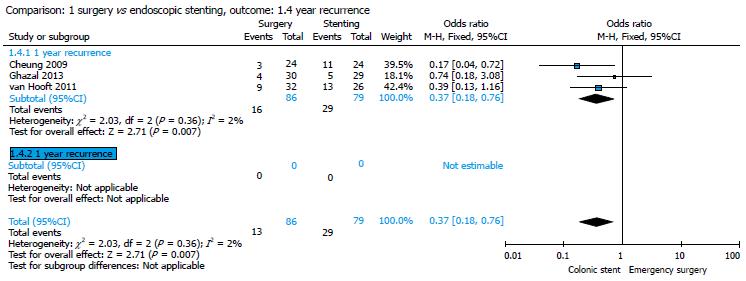

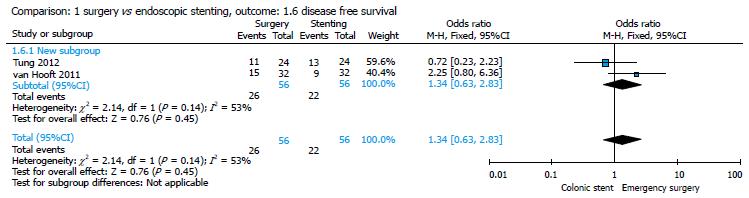

In the meta-analysis, by comparing colonic stenting (CS) as bridge to surgery and emergency surgery, the pooled analysis showed no significant difference between the two techniques in terms of mortality [odds ratio (OR) = 0.91], morbidity (OR = 2.38) or permanent stoma rate (OR = 1.67); primary anastomosis was more frequent in the stent group (OR = 0.45; P = 0.004) and stoma creation was more frequent in the emergency surgery group (OR = 2.36; P = 0.002). No statistical difference was found in disease-free survival and overall survival. The pooled analysis showed a significant difference between the colonic stent and emergency surgery groups (OR = 0.37), with a significantly higher 1-year recurrence rate in the stent group (P = 0.007).

CS improves primary anastomosis rate with significantly high 1-year follow-up recurrence and no statistical difference in terms of disease-free survival and overall survival.

Core tip: The management of patients presenting with acute large bowel obstruction caused by left-sided colorectal cancer is still debated. Recently published conflicting results regarding colonic stenting and its oncological outcome, not allowing the emergency surgeon to consider this therapeutic option, with the aim to convert an urgent situation into an elective one and to decrease the stoma creation rate. We decided to carry out a meta-analysis of all the available randomized controlled trials comparing colonic stenting vs surgical decompression to investigate the real advantage of self-expandable metallic stent placement and its oncological safety.

- Citation: De Simone B, Catena F, Coccolini F, Di Saverio S, Sartelli M, Heyer A, De Angelis N, De Angelis GL, Ansaloni L. Preoperative colonic stents vs emergency surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: Meta-analysis with systematic review of the literature. World J Meta-Anal 2017; 5(1): 1-13

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v5/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v5.i1.1

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a common malignant condition in Western countries; approximately 10%-30% of patients affected present with acute large bowel obstruction (ALBO) requiring urgent decompression. CRC presenting with obstruction is associated with increasing age, lower socioeconomic status, more advanced disease and considerably increased hospital morbidity and mortality[1]. Treatment options include resection of the obstructing tumor with primary anastomosis, proximal diversion, or insertion of a self-expandable metal stent (SEMS).

Emergency surgery (ES) for acute colonic obstruction is associated with a significant risk of mortality and morbidity and with a high percentage of stoma creation[2].

About 70% of all large bowel obstructions occur in left-sided lesions and there is still no consensus about the emergency management of the obstructed left colon cancer. Colonic stenting (CS) has been suggested as an alternative to surgery, as a bridge to surgery (BTS), as allowing time for a preoperative evaluation, as a means to improve the patient’s medical condition, and as a means to facilitate bowel decompression; it also has a palliative purpose in patients considered non-operable because of advanced neoplastic disease.

Since Dohmoto et al[3] described the use of SEMS in patients with non-resectable or metastatic rectal cancer and Tejero et al[4] published their experience of metallic stent placement in 2 patients with colonic obstruction as BTS, several studies have demonstrated that endoscopic stenting, followed by elective surgery with optimal timing (within 5-7 d)[5,6], increases the primary anastomosis rate in patients with obstructive left-sided lesion. Lately, many studies have reported conflicting results from comparison of SEMS as BTS and ES, in terms of safety, morbidity, disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS), and medium- and long-term oncological outcomes.

According to the current literature, colon perforation after SEMS placement occurs in 3.8% to 6.9% of patients treated[7], resulting in seeding of neoplastic cells in the abdominal cavity; colonic perforation after stent can be classified as: (1) immediate or delayed (technical problems are frequently responsible for immediate perforation; stent quality is an important factor affecting delayed perforation; patients in whom a SEMS was placed at the recto-sigmoid junction are at high risk of delayed perforation); (2) free, associated with fecal peritonitis, or silent (microperforation)[8].

Almost 70% of colon perforations occur in the first week after stenting and they could have a negative effect on long term survival, especially in patients whose disease is potentially curable. Maruthachalam et al[9] first reported that endoscopic insertion of colonic stents results in increased levels of CK20 mRNA in the peripheral circulation. Malgras et al[10] showed an increased metastatic process and shorter survival time in a mouse model of colonic cancer treated with SEMS.

We decided to comprehensively review the current literature and to carry out a meta-analysis of the last randomized controlled trials (RCT) published, with the aim to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CS as BTS vs ES.

We conducted an extensive literature search of the PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase and the Cochrane Library databases. We searched for all the papers in English published till February 2016 by applying combinations of the following terms: Obstructive colon cancer, colon cancer in emergency, colorectal stenting, ES for colorectal cancer, guidelines for obstructive colorectal cancer, stenting vs ES in the treatment of obstructive colorectal cancer, SEMS, stenting as BTS.

We considered for our analysis all systematic reviews, RCT, large case series, original case reports, meta-analyses, retrospective and prospective comparative studies.

The study was designed following the Prisma Statement[11].

All the collected studies, as full manuscripts, were reviewed and selected applying the following inclusion criteria: (1) RCT; (2) retrospective studies; (3) prospective studies; and (4) case matched studies, comparing CS as BTS vs ES in the treatment of the left colon obstruction caused by adenocarcinoma.

We excluded from analysis, studies evaluating stenting for benign stenosis and for right colon cancer, primary and secondary stenting in patients with advanced neoplastic disease and/or for patients who received chemotherapy with palliative treatment, and colon stenting for extrinsic tumor compression.

Two investigators, following selection criteria established before the literature search was initiated, extracted the following data from the RCT included in the meta-analysis: First name author and year of publication, country of origin, study design, whether it was a single or multicenter study, total number of patients included and number of subjects in each group (colonic stent and ES group), sex and age of patients. Clinical variables were: Tumor site, type of stent used and modality of insertion, type of surgery after stent insertion, type of surgery in emergency, data on technical and clinical success (defined as successful stent placement across the stricture and its deployment and adequate bowel decompression (within 48-72 h) from stent insertion without need for re-intervention), stenting-related complications (bleeding, stent obstruction, stent migration, bowel perforation) and elective surgery-related complications.

Primary outcomes reported for the two techniques were: Short term morbidity, in-hospital mortality, permanent stoma creation, primary anastomosis and stoma creation rate, 1-year recurrence rate, OS and DFS.

Study quality was assessed by evaluating randomization, generation of allocation sequence and allocation concealment, blinding, description of follow-up, definition of outcome measures, adequate power for clinically significant effect size, intention-to-treat analysis and baseline assessment of treatment group characteristics, according to the quality criteria suggested for RCT by Jüni et al[12].

Data analysis was performed with RevMan 5.3 software (Cochrane collaboration). The outcomes of meta-analysis were morbidity and mortality rates, permanent stoma rate, primary anastomosis and temporary stoma creation rates, 1-year recurrence rate, DFS and OS rates. The Odds ratio (OR) was used to compare the different outcomes for ES and endoscopic stenting in the groups analyzed. The P values and 95%CI were provided for all outcomes. Forest plots for all the outcomes were constructed. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

By our search, we identified 452 studies, including 57 potentially relevant studies in full-text that were reviewed by 2 investigators. Eight RCT (Table 1) were considered for meta-analysis. Eight meta-analyses and systematic reviews, 4 reviews of the literature, 17 retrospective comparative studies, 11 prospective comparative studies, 1 experimental study and 5 international guidelines were included in our comprehensive review of the literature (Figure 1).

| Ref. | Format | Country | Type of study | CS/ES | Etiology of obstruction | Site of obstruction | Colonic stent | Emergency surgery | Elective surgicaltreatment |

| van Hooft et al[16], 2008 | FT | Netherlands | MLC | 11/10 | OLCC | RS: 16 DC: 6 | Endoscopic-fluoroscopic placement of Boston Scientific WallFlex | Open or laparoscopic palliative resection or fecal diversion | None |

| Cheung et al[18], 2009 | FT | China | MNC | 24/24 | OLCC | Between the splenic flexure and the RSJ | Endoscopic-fluoroscopic placement of Boston Scientific Wallstent | Hartmann’s procedure; primary anastomosis after subtotal or total colectomy or segmental colectomy with on-table lavage according to the operators’ judgment | Elective laparoscopic-assisted colectomy |

| Alcántara et al[22], 2011 | FT | Spain | MNC | 15/13 | OLCC | SF: 6 DC: 3 Sigma: 15 RSJ: 3 Rectum sup: 1 | NA | Retrowash (Intermark Medical Interventions Ltd, Bromley, Kent, United Kingdom), a retrograde variation of the traditional anterograde lavage | Colectomy with PA: 14 HP: 1 |

| Pirlet et al[20], 2011 | FT | France | MLC | 35/32 | OLCC: 60 benign Stenosis: 3 NA: 7 | RSJ: 15 Sigma: 33 DC: 8 SF: 3 NA: 1 (10 drop-out) | Endoscopic-fluoroscopic placement of Bard nitinol uncovered self-expanding stents (Voisins le Bretonneux, France) | One-stage procedure: 14 Two-stage surgery: 8 Three-stage surgery: 2 | Colectomy with PA |

| van Hooft et al[15,16], 2011 | FT | Netherlands | MLC | 47/51 | NA | NA | Endoscopic-fluoroscopic placement of Wallstent and WallFlex colonic stents (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) | Treatment according to conventional standards | NA |

| Cheung et al[13], 2012 | FT | South Korea | MLC | 58/62 | OLCC | Ascending colon: 10 Transverse: 9 DC: 14 Sigma: 65 Rectum: 25 | Taewoong D-type uncovered stent; Boston scientific WallFlex stent fluoroscopy placement with through the scope or over the wire method | Palliative intent: 58 BTS: 65 | |

| Ghazal et al[19], 2012 | FT | Egypt | MNC | 30/30 | OLCC | RSJ: 12-10 Sigma: 14-17 DC: 4-3 | Endoscopic placement under fluoroscopic guidance | Total abdominal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis by laparotomy | Left hemicolectomy or anterior resection |

| Tung et al[17], 2012 | FT | China | MNC | 24/24 | OLCC | NA | Endoscopic-fluoroscopic placement of Boston Scientific Wallstent | NA | LR |

Four RCT were published between January 2012 and February 2016: (1) Cheung et al[13] carried out a randomized multicenter (12 university Korean hospitals involved) prospective study on 123 patients with malignant colonic obstruction treated by stenting, 58 of them with palliative intent and 65 as BTS, to determine and compare the clinical outcome and safety of the Taewoong D-type uncovered stent (Taewoong Medical Co., Gimpo, South Korea) and the Boston Scientific WallFlex stent (Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, MA, United States); (2) Sloothaak et al[14] reported oncological data of the Dutch Stent-In 2 RCT[15,16] stopped prematurely in March 2010 because the clinical stent or procedure-related perforation rate was 13% and occult perforations were revealed in a further 10% of the resected specimens; follow-up time for this study was mean 45 mo for the ES group (32 patients) and 41 mo for the colonic stent as BTS (26 patients); (3) Tung et al[17] reported long-term follow-up (32 mo for the open surgery group and 65 mo for the endo-laparoscopic group) data of the RCT conducted by Cheung et al[18] with the aim to compare the endo-laparoscopic approach and open surgery in the treatment of obstructing left-sided colon cancer[17]; and (4) Ghazal et al[19] conducted a RCT to compare the procedures of endoscopic stenting followed by elective colectomy vs total abdominal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis in the management of acute obstructed carcinoma of the left colon[19].

Data from 8 RCT[15-22] were analyzed with a total of 361 patients: 182 who received CS as BTS and 179 who underwent surgery in emergency. The location of the tumor was well indicated in all the RCT (transverse colon; splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectosigmoid).

Different colonic stents were used across the studies: Van Hooft et al[15,16] used both the Boston Scientific WallFlex and Wallstent; Cheung et al[18] used the Boston Scientific Wallstent; Pirlet et al[20] used the Bard nitinol uncovered stent; Ho et al[21] used the Boston Scientific WallFlex, while Alcántara et al[22] and Ghazal et al[19] did not indicate the type of stent used.

The stent placement was performed by an experienced endoscopist and/or radiologist in the studies of Cheung et al[13], van Hooft et al[15], Pirlet et al[20] and Alcántara et al[22]. Ho et al[21] reported that the stent was inserted by an endoscopist or endoscopist-surgeon. Ghazal et al[19] did not reported this information.

The colonic stent group was surgically treated by elective colic resection with 1-stage technique, by laparoscopic approach[17,18], laparotomy or Hartmann’s procedures. In the ES group, the surgical technique employed was decided by the surgeon, case by case. All the patients in the ES group of the Ghazal et al[19] study had undergone total abdominal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis.

A sensitivity analysis using random vs fixed-effect models for all the outcomes showed a limited difference between the OR and the corresponding 95%CI. Statistical tests confirmed the presence of between-study heterogeneity; therefore, a random-effects model was utilized for the statistical analysis.

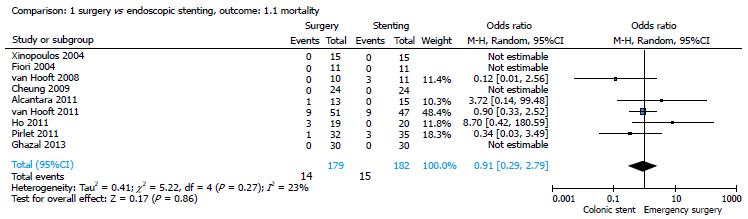

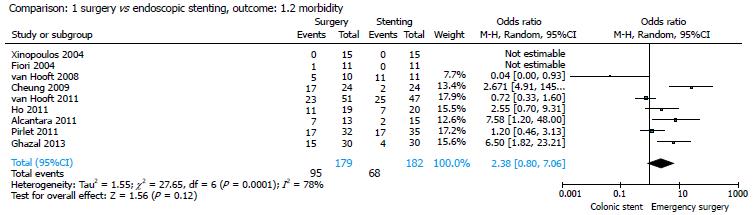

All studies provided data on mortality[14-22]. There were 14/179 (7.82%) deaths in the surgery group and 15/182 (8.2%) deaths in the stent group; the pooled analysis showed no significant differences between the two strategies (OR = 0.91; 95%CI: 0.29-2.79) (Figure 2). All the studies considered reported medical and surgical complications in the two groups of patients. The morbidity rate was 37.36% (68/182) in the stent group and 53.07% (95/179) in the surgical group and, also for this parameter, the pooled analysis showed no significant differences between the two strategies (OR = 2.38; 95%CI: 0.80-7.06) (Figure 3).

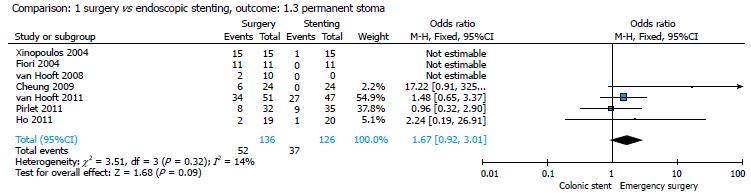

Only 5 studies were considered for this parameter (16-20). The permanent stoma rate was 37/126 (29.36%) in the stent group and 52/136 (38.23%) in the surgical group; the pooled analysis showed no significant differences between the two groups (P = 0.09) (Figure 4), with an OR of 1.67 (95%CI: 0.92-3.01).

By comparing ES and CS in studies that analyzed the use of stenting as a BTS procedure[14,16,17,19,20,22], the pooled analysis showed that primary anastomosis was significantly frequent in the stent group (121/171, 70.76%) as compared to the surgical group (95/169, 56.21%; Figure 5), with an OR of 0.45 (95%CI: 0.26-0.77; P = 0.004), and that the stoma creation was more frequent in the surgical group (77/169, 45.56%) as compared to the stent group (52/170, 30.58%; Figure 6), with an OR of 2.36 (95%CI: 1.37-4.07; P = 0.002).

Only 3 studies were considered[16,20,22] for this parameter. One-year recurrence rate was 18.60% (16/86) in the surgery group and 36.70% (29/79) in the stent group, with an OR of 0.37 (95%CI: 0.18-0.76). The pooled analysis showed a significant difference between the two groups with a significant higher 1-year recurrence rate in the stent group (P = 0.007) (Figure 7).

Two studies reported data about DFS[20,21]; the statistical analysis showed a higher DFS in the surgery group (26/56, 46.42%) as compared to the stent group (22/56, 39.28%) with no significant difference in the pooled analysis (P = 0.45) and an OR of 1.34 (95%CI: 0.63-2.83) (Figure 8).

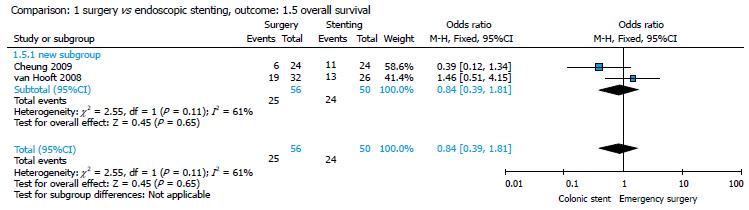

Cheung et al[18] and van Hooft et al[16] reported data about OS; the pooled analysis showed no significant difference between the two groups (ES group: 25/56, 44.64% vs stent group: 24/50, 48%; P = 0.65) and an OR of 0.84 (95%CI: 0.39-1.81) (Figure 9).

ALBO presents a challenge to any surgeon. Distended unprepared bowel, patient dehydration, advanced disease and frequent need for surgery out of hours, often at night, are all factors that predispose the patient to complications. Its surgical management is still debated and includes: (1) primary resection and anastomosis (1-stage procedure), which prevents the confection of a loop colostomy but presents the risk of anastomotic leakage; (2) Hartmann’s procedure, which prevents anastomotic leakage but needs a second operation to reverse the colostomy; (3) the 3-stage procedure (decompressive colostomy-colic resection-colostomy closure); (4) subtotal or total colectomy with/without primary anastomosis, which is indicated in diastatic colon perforation or synchronous right colonic cancer; and (5) temporary or definitive loop colostomy/ileostomy, in case of important bowel dilatation proximal to obstruction, advanced neoplastic disease or peritoneal carcinomatosis[1,2].

Many available studies reported the increasing number of surgical procedures involving the creation of a diverting or permanent stoma and this seems to increase with age, decreasing the quality of life of patients[23,24].

The “ideal” operation is the elective one. The immediate colic resection with primary anastomosis represents the gold standard in patients with low risk. A temporary de-functioning colostomy or ileostomy could be proposed to patients with an intermediate anesthetic risk. In high-risk cases, advanced obstruction, simultaneous colonic perforation, metastatic or locally advanced disease, Hartmann’s operation should be preferred. Colonic stents represent the best option when skills are available[2].

CS as BTS seems to provide a good alternative therapeutic option to convert an emergency clinical situation into a more elective one.

SEMS placement can be associated with complications, such as perforation, migration, tumor in-growth, stool impaction, bleeding and pain.

The perforation rate ranged from 0% to 83% and the overall risk of perforation was about 5%, which is a relatively low risk, but the mortality rate of patients with perforations was 16%[8].

Van Hooft et al[15,16] reported 6/47 stent-related perforations and Pirlet et al[20] reported 2 stent perforations and 8 silent perforations in 30 patients randomized to CS as BTS.

The endoscopist’s experience, the type of colic obstruction (partial or complete), the type of stent and the insertion technique are fundamental to reach CS technical and clinical success[25].

CS is more likely to be successful in shorter, malignant strictures with less angulation, distal to the obstruction[26].

Geraghty et al[27] reported that technical success and good outcome for the emergency management of malignant left colon obstruction (MLBO) by SEMS insertion is higher for experienced operators who had performed more than 10 procedures, using the through-the-scope endoscopy technique.

Gianotti et al[28], evaluating prospectively short- and long-term results from CS as BTS, showed a benefit for the CS group compared to ES group and concluded that this results from the experience of the endoscopist and the relatively low rate of complete colonic obstructions included in the study.

Mehmood et al[29] reported that CS can be performed by an endoscopist without radiologist support if adequately trained, with good outcomes, highlighting the central role of the endoscopist.

SEMS can be divided into two types: Uncovered and (fully and partially) covered. Tumor in-growth occurs often with uncovered SEMS, and migration occurs often with covered SEMS[30].

Selection of the appropriate stent is very important for outcomes, considering material, design, diameter, length, radial force, flexibility, foreshortening ratio and delivery system, but there is no evidence to indicate which stent type is superior.

Cheung et al[13] recently conducted a multi-center, randomized, prospective, comparative study aimed to compare the efficacy and complication rates of the D-type colonic stent with those of the WallFlex stent; both stents were uncovered, with different radial and axial force, to reduce the excessive pressure on the ends, which could result in contact with the normal mucosa of the colon, increasing risk of perforation. Perforation occurred in 5/58 patients treated with colonic stent, including 4 with the WallFlex stent and 1 with the D-type stent, but the difference was not statistically significant[13].

van Halsema et al[7], in their meta-analysis, noted that of the 9 most frequently used stent types, the WallFlex, Comvi, and Niti-S D-type had a higher perforation rate (> 10%). A lower perforation rate (< 5%) was found for the Hanarostent and the Niti-S covered stents. Risk factors for perforation include benign etiology of the stricture and chemotherapy with bevacizumab, as confirmed by others studies[7,31-33].

Many studies were proposed to investigate the advantages and disadvantages of CS compared to ES in the management of acute colorectal obstruction. Data confirmed short-term safety and efficacy of SEMS placement as BTS. The conflicting data reported recently by 3 RCT, stopped prematurely, have opened the debate on the efficacy and safety of the use of SEMS to treat potentially curable patients presenting with MLBO[15,20,22].

Van Hooft et al[15,16] did not observe clinical advantages of CS as compared to ES. During their RCT, an interim analysis showed an increase in absolute risk of 30-d morbidity in the CS group as well as a high perforation rate (13%). In this trial, the ES group had an increased stoma rate after initial intervention (75% in ES vs 51% in CS), but a reduced frequency of stoma-related problems (1.9% in ES vs 10.6% in CS). The differences in the stoma rate disappeared at last follow-up (67% in ES vs 57% in CS) due to the high leakage rate of primary anastomosis in the stent group.

Pirlet et al[20] failed to demonstrate that CS significantly decreased the need for a stoma, compared to ES. No significant difference was noted regarding the stoma rate, but the high number of stent-related adverse events (6.6% of perforations) and the low technical success rate for stent insertion (47%) led to premature closure of the trial[20].

In contrast, Alcántara et al[22] closed their study prematurely because of high morbidity, in particular the high incidence of anastomotic leakage in the ES group (30.7% in ES with intraoperative colonic lavage vs 0% in patients having CS)[22].

Since the publication of these data, several meta-analyses were designed to investigate the superiority of the use of CS as BTS compared with ES alone in the treatment of potentially curable patients presenting with MLBO.

Cennamo et al[34] confirmed that in patients with ALBO, stent placement improves primary anastomosis without decreasing mortality and morbidity rates.

Zhang et al[35] reported that stent placement as BTS did not adversely affect mortality and long-term survival.

Cirocchi et al[36] analyzed data from about 197 patients, 97 of them treated with CS, to assess the effectiveness of CS used as BTS in the management of MLBO. The authors showed that when used as BTS, CS improves the primary anastomosis rate (64.9% vs 55% respectively for CS and ES groups; P = 0.003) and decreases the overall stoma rate (45.3% vs 62% respectively for the CS and ES groups; P = 0.02)[36].

De Ceglie et al[37] showed that CS offers advantages over ES in terms of increase in primary anastomosis, successful primary anastomosis and reduction of stoma creation, infections and other morbidities; no significant statistical difference was found between CS and ES in terms of length of hospitalization, preoperative mortality and long-term survival.

Huang et al[25] analyzed data from 7 RCT comparing CS and ES and reported that, compared with the ES group, the CS group achieved significantly more favorable rates of permanent stoma, primary anastomosis, wound infection and overall complications; no significant difference was found between the two groups for anastomotic leakage, mortality or intra-abdominal infection.

Results of our meta-analysis confirmed that in the group of patients treated with CS as BTS, primary anastomosis is significantly more frequent, as stoma creation rate is significantly higher in the ES group. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in permanent stoma rate (Figures 4-6).

The negative long-term oncological outcomes of SEMS insertion have to be proven and are still debated after the data reported by Maruthachalam et al[9] and Malgras et al[10]. Surely, the enforced radial dilatation by SEMS suggests the possibility of increased risk of perforation and tumor manipulation that can induce dissemination of cancer cells into the peritoneal cavity.

Matsuda et al[38] conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate long-term outcomes of colonic stent insertion followed by surgery for ALBO. The authors included 11 studies for analysis, with a total of 1136 patients, of whom 432 (38%) underwent CS as BTS and 704 (62%) underwent ES. OS, DFS and recurrence did not differ significantly between the CS as BTS and ES groups.

Kavanagh et al[39] conducted an observational comparative study to evaluate medium-term oncological outcomes of CS as BTS and ES with an intention to treat analysis. Data showed no difference in cancer-specific and all-cause mortality between both groups; there were 3 cancer-related deaths in the CS group and 4 in the ES group. Median follow-up (mo) in the CS and ES group was 27.4 (range: 1-81) and 26[39]. Disease recurrence occurred in 4 patients in the CS group and 6 patients in the ES group; sites of recurrence in the CS were local/peritoneal in 2 patients and liver in 2 patients. Both local recurrences occurred in patients who had undergone R1 resections. In the ES group, there was 1 local/liver, 2 peritoneal, and 3 liver recurrences. The local recurrence occurred in a single patient who had a R1 resection. Kavanagh et al[39] reported the histological evidence of clinically silent tumor microperforations in 3 patients in the CS group (13%), in comparison with 2 (7%) tumor microperforations in the ES group; this suggested an occasional occurrence in the absence of stent deployment.

Gorissen et al[40] reported that SEMS was associated with an increased local recurrence rate in patients aged ≤ 75 years. In younger patients treated with CS, a significantly higher local recurrence rate was observed at the end of the follow-up (32% vs 8%; P = 0.038). Of 20 local recurrences, 12 were diffusely peritoneal, 5 were at the large bowel anastomosis/side wall, 2 were ovarian and 1 was on the small bowel.

Sloothaak et al[14] reported data about disease recurrence, DFS, disease-specific survival and OS for patients involved in the Dutch Stent-In 2 trial[14-16]. Fifty-eight patients were included in the analysis. Median follow-up was 4 mo and 41 mo in the ES and CS groups respectively. Loco-regional or distant disease recurrence developed in 9/32 patients in the ES group and 13/26 in the CS group. DFS was worst after a stent-related perforation. The OS rate was 50% for patients with a stent-related perforation and was worse than the rate of 62% in patients without stent-related perforation[14].

Sabbagh et al[41] retrospectively analyzed data from 48 patients in the CS group and 39 in the ES group, using a propensity score to correct for selection bias. The authors reported worse OS and DFS for patients with MLBO with SEMS insertion, compared with ES. In the overall population, OS (P = 0.001) and 5-year OS (P = 0.0003) were significantly lower in the CS group than in the ES group, and 5-year cancer-specific mortality was significantly higher in the CS group (P = 0.02). Five-year DFS, recurrence rate, and mean time to recurrence were better in the ES group (no statistically significant difference). For patients with no metastases or perforations at hospital admission, OS (P = 0.003) and 5-year OS (30% vs 67%, respectively, P = 0.001) were significantly lower in the CS group than in the ES group[41]. The same authors wanted to explain these data by analyzing pathological specimens from the CS and the ES groups in a case-matched analysis (with the groups matched for the T stage). A total of 84 patients were included in the study (50 in the CS group). Twenty-five patients in the CS group were matched with 25 patients of the surgery-only group. Tumor ulceration (P = 0.0001), peri-tumor ulceration (P = 0.0001), perineural invasion (P = 0.008) and lymph node invasion (P = 0.005) were significantly more frequent in the CS group. In a multivariate analysis of the CS group, T4 status and tumor size were significant risk factors for microscopic perforation, perineural invasion and lymph node invasion[42].

Knight et al[43] decided to carry out a retrospective cohort study to determine if preoperative stenting adversely affects long-term survival. The single-center study compared a group of patients having preoperative stenting (group A) with a group of patients having elective surgery for Dukes' B and C cancer, excluding mid and low rectal tumors (group B). The 30-d mortality rates for groups A and B were 6.7% (1 patient) and 5.7% (5 patients) respectively. The 5-year survival rates were 60% and 58% respectively, with a P-value of 0.96. Knight et al[43] concluded that patients undergoing CS as BTS have the same long-term survival as those undergoing elective surgery.

Park et al[44] retrospectively analyzed data from 67 patients who had undergone SEMS placement as BTS and 35 patients treated by ES, to compare surgical and oncologic outcomes of the groups. The CS group had a higher laparoscopic resection rate (67.2% vs 31.4%, P = 0.001) with a lower conversion rate (4.3% vs 35.3%, P = 0.003). The rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis, recurrence-free and OS were not significantly different between the two groups[44].

Kim et al[45] also carried out a retrospective analysis of data from 43 patients who had undergone radical resection after preoperative CS and 48 who had undergone ES with curative intent to compare short- and long-term outcomes between the two groups. The 5-year DFS and 5-year OS rates were not significantly different between the CS and ES groups[45].

Our meta-analysis showed that 16/86 (18.60%) patients in the ES group and 29/79 (36.70%) patients in the CS group presented with a recurrence at the 1-year follow-up, with a statistically significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.007) (Figure 7). No statistically significant difference was found in terms of DFS and OS between the groups (Figures 8 and 9).

Considering the available data, the emergency surgeon is not allowed to treat with SEMS potentially curable patients presenting with obstructing left-sided colon cancer.

The World Society of Emergency Surgeons, after a consensus conference, stated that colonic stents represent a valuable option both for palliation and as a bridge to elective surgery, when skills are available, to treat patients presenting with obstructing left-sided colon cancer and no signs of perforations. High clinical and technical expertise is mandatory to obtain good results; consequently, the group suggests that SEMS should be used as a bridge to elective surgery in referral center hospitals with specific expertise, in selected patients, and that CS should be preferred to colostomy for palliation in patients not treated with bevacizumab-based therapy, since this technique is associated with similar mortality/morbidity rates and shorter hospital stay, compared to surgery, avoiding the high healthcare costs related to stoma[2,32].

The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy does not recommend SEMS placement as a standard treatment of symptomatic MLBO. It can, however, be considered for patients with potentially curable ALBO at high risk of postoperative mortality (American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status ≥ III and/or age > 70 years) as an alternative to ES. Moreover, it is recommended as the preferred treatment for palliation, except in patients treated or considered for treatment with anti-angiogenic drugs, such as bevacizumab[46].

The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma conditionally recommended CS (if available) as initial therapy for MLBO, because stent use was associated with decreased mortality and morbidity rates[47].

The Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends CS as BTS in order to avoid high morbidity related to ES, above all in patients with unresectable CRC, because SEMS placement can relieve symptoms, improve quality of life and allow chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for palliation[48].

In conclusion, CS improves primary anastomosis rate, with a low stoma creation in comparison with ES. At 1-year follow-up, the recurrence rate is higher in patients treated with stent, with no statistical difference in terms of DFS and OS. CS is a therapeutic option to take into consideration, when skills are adequate, to treat patients unfit for surgery with palliative intent and considering the high healthcare costs related to stoma.

Considering the available data about oncological outcome of CS, surgery is the only treatment to offer young patients presenting with a potentially curable acute colorectal obstruction.

Colonic stenting seems to be a good therapeutic option to convert an urgent situation into an elective one. Recently published conflicting results about oncological safety of this technique, used as a bridge to surgery, vs emergency surgery, do not allow for surgeons to treat potentially curable patients presenting with large bowel obstruction with stenting.

Emergency surgery has high morbidity and mortality rates still. The use of colonic stenting in the management of patients presenting with large bowel obstruction can help to decrease morbidity and mortality, delaying surgery. The problem is that colonic stenting can potentially determinate the spreading of tumor cells, but no available data can confirm that it can affect disease-free survival and overall survival rates.

In the present study, the authors demonstrated that colonic stenting improves primary anastomosis rate, with a low stoma creation. At 1-year follow-up, the recurrence rate is higher in patients treated with stent, with no statistical difference in terms of disease-free survival and overall survival.

Colonic stenting is a therapeutic option to take into consideration, when skills are adequate, to treat patients unfit for surgery, with palliative intent, considering the high healthcare costs related to stoma. Considering the available data about oncological outcome of stunting in emergency, surgery is the only treatment to offer young patients presenting with a potentially curable acute colorectal obstruction.

This meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing colonic stenting vs emergency surgery in the management of left large bowel obstruction and the systematic review of all the other available studies adds useful information for practice and research.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): B

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ayscue JM S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | De Simone B, Catena F. Emergency Surgery for Colorectal Cancer in Patients Aged Over 90 Years: Review of the Recent Literature. J Tumor. 2015;4:349-353 Available from: http: //www.ghrnet.org/index.php/JT/article/view/1589. |

| 2. | Ansaloni L, Andersson RE, Bazzoli F, Catena F, Cennamo V, Di Saverio S, Fuccio L, Jeekel H, Leppäniemi A, Moore E. Guidelenines in the management of obstructing cancer of the left colon: consensus conference of the world society of emergency surgery (WSES) and peritoneum and surgery (PnS) society. World J Emerg Surg. 2010;5:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dohmoto M, Hünerbein M, Schlag PM. Application of rectal stents for palliation of obstructing rectosigmoid cancer. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:758-761. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Tejero E, Fernández-Lobato R, Mainar A, Montes C, Pinto I, Fernández L, Jorge E, Lozano R. Initial results of a new procedure for treatment of malignant obstruction of the left colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:432-436. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Abdussamet Bozkurt M, Gonenc M, Kapan S, Kocatasş A, Temizgönül B, Alis H. Colonic stent as bridge to surgery in patients with obstructive left-sided colon cancer. JSLS. 2014;18:pii: e2014.0016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sirikurnpiboon S, Awapittaya B, Jivapaisarnpong P, Rattanachu-ek T, Wannaprasert J, Panpimarnmas S. Bridging metallic stent placement in acute obstructed left sided malignant colorectal cancer: optimal time for surgery. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97 Suppl 11:S81-S86. [PubMed] |

| 7. | van Halsema EE, van Hooft JE, Small AJ, Baron TH, García-Cano J, Cheon JH, Lee MS, Kwon SH, Mucci-Hennekinne S, Fockens P. Perforation in colorectal stenting: a meta-analysis and a search for risk factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:970-982.e7; quiz 983.e2, 983.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim EJ, Kim YJ. Stents for colorectal obstruction: Past, present, and future. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:842-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Maruthachalam K, Lash GE, Shenton BK, Horgan AF. Tumour cell dissemination following endoscopic stent insertion. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1151-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malgras B, Brullé L, Lo Dico R, El Marjou F, Robine S, Therwath A, Pocard M. Insertion of a Stent in Obstructive Colon Cancer Can Induce a Metastatic Process in an Experimental Murine Model. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S1475-S1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9207] [Cited by in RCA: 8015] [Article Influence: 534.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42-46. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Cheung DY, Kim JY, Hong SP, Jung MK, Ye BD, Kim SG, Kim JH, Lee KM, Kim KH, Baik GH. Outcome and safety of self-expandable metallic stents for malignant colon obstruction: a Korean multicenter randomized prospective study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3106-3113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sloothaak DA, van den Berg MW, Dijkgraaf MG, Fockens P, Tanis PJ, van Hooft JE, Bemelman WA. Oncological outcome of malignant colonic obstruction in the Dutch Stent-In 2 trial. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1751-1757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van Hooft JE, Fockens P, Marinelli AW, Timmer R, van Berkel AM, Bossuyt PM, Bemelman WA. Early closure of a multicenter randomized clinical trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgery for stage IV left-sided colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 2008;40:184-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van Hooft JE, Bemelman WA, Oldenburg B, Marinelli AW, Lutke Holzik MF, Grubben MJ, Sprangers MA, Dijkgraaf MG, Fockens P. Colonic stenting versus emergency surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:344-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tung KL, Cheung HY, Ng LW, Chung CC, Li MK. Endo-laparoscopic approach versus conventional open surgery in the treatment of obstructing left-sided colon cancer: long-term follow-up of a randomized trial. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2013;6:78-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cheung HY, Chung CC, Tsang WW, Wong JC, Yau KK, Li MK. Endolaparoscopic approach vs conventional open surgery in the treatment of obstructing left-sided colon cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1127-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ghazal AH, El-Shazly WG, Bessa SS, El-Riwini MT, Hussein AM. Colonic endolumenal stenting devices and elective surgery versus emergency subtotal/total colectomy in the management of malignant obstructed left colon carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1123-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pirlet IA, Slim K, Kwiatkowski F, Michot F, Millat BL. Emergency preoperative stenting versus surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1814-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ho KS, Quah HM, Lim JF, Tang CL, Eu KW. Endoscopic stenting and elective surgery versus emergency surgery for left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a prospective randomized trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:355-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Alcántara M, Serra-Aracil X, Falcó J, Mora L, Bombardó J, Navarro S. Prospective, controlled, randomized study of intraoperative colonic lavage versus stent placement in obstructive left-sided colonic cancer. World J Surg. 2011;35:1904-1910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Anaraki F, Vafaie M, Behboo R, Maghsoodi N, Esmaeilpour S, Safaee A. Quality of life outcomes in patients living with stoma. Indian J Palliat Care. 2012;18:176-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wong SK, Young PY, Widder S, Khadaroo RG. A descriptive survey study on the effect of age on quality of life following stoma surgery. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2013;59:16-23. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Huang X, Lv B, Zhang S, Meng L. Preoperative colonic stents versus emergency surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:584-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Boyle DJ, Thorn C, Saini A, Elton C, Atkin GK, Mitchell IC, Lotzof K, Marcus A, Mathur P. Predictive factors for successful colonic stenting in acute large-bowel obstruction: a 15-year cohort analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:358-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Geraghty J, Sarkar S, Cox T, Lal S, Willert R, Ramesh J, Bodger K, Carlson GL. Management of large bowel obstruction with self-expanding metal stents. A multicentre retrospective study of factors determining outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:476-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gianotti L, Tamini N, Nespoli L, Rota M, Bolzonaro E, Frego R, Redaelli A, Antolini L, Ardito A, Nespoli A. A prospective evaluation of short-term and long-term results from colonic stenting for palliation or as a bridge to elective operation versus immediate surgery for large-bowel obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:832-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mehmood RK, Parker J, Kirkbride P, Ahmed S, Akbar F, Qasem E, Zeeshan M, Jehangir E. Outcomes after stenting for malignant large bowel obstruction without radiologist support. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6309-6313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kim BC, Han KS, Hong CW, Sohn DK, Park JW, Park SC, Kim SY, Baek JY, Choi HS, Chang HJ. Clinical outcomes of palliative self-expanding metallic stents in patients with malignant colorectal obstruction. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:258-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cetinkaya E, Dogrul AB, Tirnaksiz MB. Role of self expandable stents in management of colorectal cancers. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Mutri V, Minardi ME, Eusebi LH, Ceroni L, Laterza L, Ansaloni L, Pinna AD, Salfi N. Does stent placement for advanced colon cancer increase the risk of perforation during bevacizumab-based therapy? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1174-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Imbulgoda A, MacLean A, Heine J, Drolet S, Vickers MM. Colonic perforation with intraluminal stents and bevacizumab in advanced colorectal cancer: retrospective case series and literature review. Can J Surg. 2015;58:167-171. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Cennamo V, Luigiano C, Coccolini F, Fabbri C, Bassi M, De Caro G, Ceroni L, Maimone A, Ravelli P, Ansaloni L. Meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing endoscopic stenting and surgical decompression for colorectal cancer obstruction. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:855-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhang Y, Shi J, Shi B, Song CY, Xie WF, Chen YX. Self-expanding metallic stent as a bridge to surgery versus emergency surgery for obstructive colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:110-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cirocchi R, Farinella E, Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Listorti C, Boselli C, Parisi A, Noya G, Sagar J. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic colonic stenting as a bridge to surgery in the management of intestinal obstruction due to left colon and rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. 2013;22:14-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | De Ceglie A, Filiberti R, Baron TH, Ceppi M, Conio M. A meta-analysis of endoscopic stenting as bridge to surgery versus emergency surgery for left-sided colorectal cancer obstruction. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:387-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Matsuda A, Miyashita M, Matsumoto S, Matsutani T, Sakurazawa N, Takahashi G, Kishi T, Uchida E. Comparison of long-term outcomes of colonic stent as “bridge to surgery” and emergency surgery for malignant large-bowel obstruction: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:497-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kavanagh DO, Nolan B, Judge C, Hyland JM, Mulcahy HE, O’Connell PR, Winter DC, Doherty GA. A comparative study of short- and medium-term outcomes comparing emergent surgery and stenting as a bridge to surgery in patients with acute malignant colonic obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:433-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Gorissen KJ, Tuynman JB, Fryer E, Wang L, Uberoi R, Jones OM, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. Local recurrence after stenting for obstructing left-sided colonic cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1805-1809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sabbagh C, Browet F, Diouf M, Cosse C, Brehant O, Bartoli E, Mauvais F, Chauffert B, Dupas JL, Nguyen-Khac E. Is stenting as “a bridge to surgery” an oncologically safe strategy for the management of acute, left-sided, malignant, colonic obstruction? A comparative study with a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;258:107-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sabbagh C, Chatelain D, Trouillet N, Mauvais F, Bendjaballah S, Browet F, Regimbeau JM. Does use of a metallic colon stent as a bridge to surgery modify the pathology data in patients with colonic obstruction? A case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3622-3631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Knight AL, Trompetas V, Saunders MP, Anderson HJ. Does stenting of left-sided colorectal cancer as a “bridge to surgery” adversely affect oncological outcomes? A comparison with non-obstructing elective left-sided colonic resections. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1509-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Park SJ, Lee KY, Kwon SH, Lee SH. Stenting as a Bridge to Surgery for Obstructive Colon Cancer: Does It Have Surgical Merit or Oncologic Demerit? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:842-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kim HJ, Huh JW, Kang WS, Kim CH, Lim SW, Joo YE, Kim HR, Kim YJ. Oncologic safety of stent as bridge to surgery compared to emergency radical surgery for left-sided colorectal cancer obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3121-3128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | van Hooft JE, van Halsema EE, Vanbiervliet G, Beets-Tan RG, DeWitt JM, Donnellan F, Dumonceau JM, Glynne-Jones RG, Hassan C, Jiménez-Perez J. Self-expandable metal stents for obstructing colonic and extracolonic cancer: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2014;46:990-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ferrada P, Patel MB, Poylin V, Bruns BR, Leichtle SW, Wydo S, Sultan S, Haut ER, Robinson B. Surgery or stenting for colonic obstruction: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:659-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Lee KJ, Kim SW, Kim TI, Lee JH, Lee BI, Keum B, Cheung DY, Yang CH. Evidence-based recommendations on colorectal stenting: a report from the stent study group of the korean society of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:355-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |