Published online Aug 26, 2016. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v4.i4.88

Peer-review started: February 25, 2016

First decision: April 11, 2016

Revised: May 22, 2016

Accepted: June 14, 2016

Article in press: June 16, 2016

Published online: August 26, 2016

Processing time: 184 Days and 5.3 Hours

To assess the effectiveness of Daikenchuto for patients with postoperative adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO).

A systematic search of PubMed (MEDLINE), CINAHL, the Cochrane Library and Ichushi Web was conducted, and the reference lists of review articles were hand-searched. The outcomes of interest were the incidence rate of surgery, the length of hospital days and mortality. The quality of the included studies, publication bias and between-study heterogeneity were also assessed.

Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and three retrospective cohort studies were selected for analysis. In the three RCTs, Daikenchuto significantly reduced the incidence of surgery (pOR = 0.13; 95%CI: 0.03-0.50). Similarly, Daikenchuto significantly reduced the incidence of surgery (pOR = 0.53; 95%CI: 0.32-0.87) in the three cohort studies. The length of hospital stay and mortality were not measured or described consistently.

The present meta-analysis demonstrates that administering Daikenchuto is associated with a lower incidence of surgery for patients with postoperative ASBO in the Japanese population. In order to better generalize these results, additional studies will be needed.

Core tip: Daikenchuto, a traditional herbal medicine, is commonly used by gastroenterologists for postoperative adhesive small bowel obstruction in Japan. However, the effectiveness of Daikenchuto has not been systemically investigated. The systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that Daikenchuto is associated with a lower incidence of surgery for patients with postoperative adhesive bowel obstruction in the Japanese population.

- Citation: Ukai T, Shikata S, Kassai R, Takemura Y. Daikenchuto for postoperative adhesive small bowel obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Meta-Anal 2016; 4(4): 88-94

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v4/i4/88.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v4.i4.88

Adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO) is a common complication for patients with a history of abdominal surgery. ASBO accounts for up to 6% of all surgical admissions and 60% to 70% of small bowel obstruction[1,2]. Conservative management is chosen for patients with no strangulation or peritonitis, patients who underwent surgery more than six weeks before ASBO, patients with partial ASBO and patients with signs of resolution on admission[3]. Conservative management is successful in 73% to 90% of patients[4,5], but approximately one-fifth of patients later require surgery.

Essential conservative management includes decompression using a long tube or nasogastric tube intubation and intravenous fluid supplementation. According to guidelines for ASBO[3], other supplementary non-operative management options include water-soluble contrast agent administration[6], oral therapy with magnesium oxide, Lactobacillus acidophilus and simethicone[7], and hyperbaric oxygen therapy[8]. Water-soluble contrast agent administration, in particular, has the diagnostic value of predicting the need for surgery while the procedure itself also has therapeutic value[9].

Daikenchuto, a traditional herbal medicine, is frequently used by gastroenterologists in Japan for patients with ASBO[10] as well as chronic constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease and paralytic ileus[11-14]. It comprises extract granules of processed ginger (kankyo), ginseng (ninjin) and zanthoxylum fruit (sansho). Basic research has shown several pharmacological mechanisms of Daikenchuto, including an increase in the blood flow of the intestinal tract, activation of intestinal motility, and prevention of bacterial translocation[15-17]. Recently, increasing evidence from clinical research has been accumulated[10]. However, while it is already widely used, no systematic analysis of the research has been conducted. The objective of this study was to examine the effectiveness of Daikenchuto in patients who developed postoperative ASBO.

A systematic review was conducted, and the results were described according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement[18].

We systematically searched MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, the Cochrane library and Ichushi Web, which is the largest medical article database in Japan, in November 2014. The MEDLINE search was conducted using the free-text words “Daikenchuto”, “Dai-kenchu-to”, “DKT” and “TJ-100”. A similar literature search was conducted in the other three databases. References of review articles were also hand-searched.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational studies with exposure and control groups; (2) the participants were patients who developed postoperative ASBO; (3) daikenchuto was administered enterally; and (4) the study was performed in humans. No restriction was placed on the language. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) observational studies without controls; (2) Daikenchuto was administered to prevent postoperative adhesive small bowel obstruction; and (3) experimental animal research studies.

The outcomes of interest were the incidence rate of surgery, the length of hospital stay, and mortality.

Two researchers (Ukai T and Shikata S) independently assessed the quality of each trial using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)[19] for RCTs and the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOQAS)[20] for observational studies. The CASP asks six questions regarding the quality of RCTs. The NOQAS consists of three domains: Selection, comparability and outcome; the quality is assessed by the number of stars, with each domain having a maximum of four stars, two stars and three stars, respectively. The extracted data included the first author, year of publication, country, number of participants allocated to each group, and dosage of Daikenchuto.

The meta-analysis was conducted using the software Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager (version 5.3). All statistical analyses were performed using the Mantel-Haenszel method[21], and the summary statistics were described with odds ratios (ORs). An OR less than one favored the intervention group, and the point estimate of the OR was considered statistically significant at the 0.05 level if the 95%CI did not include the value of one. A fixed-effects model was initially adapted for all outcome measures. We tested for homogeneity among the studies by calculating the I2 value. I2 can be calculated as I2 = 100% × (Q - df)/Q, where Q is Cochran’s heterogeneity statistic and df the degrees of freedom[22]. We defined I2 values of less than 25% as low heterogeneity, 25% to 50% as moderate heterogeneity and more than 50% as high heterogeneity[22]. If the hypothesis of homogeneity was rejected, a random-effects model was employed.

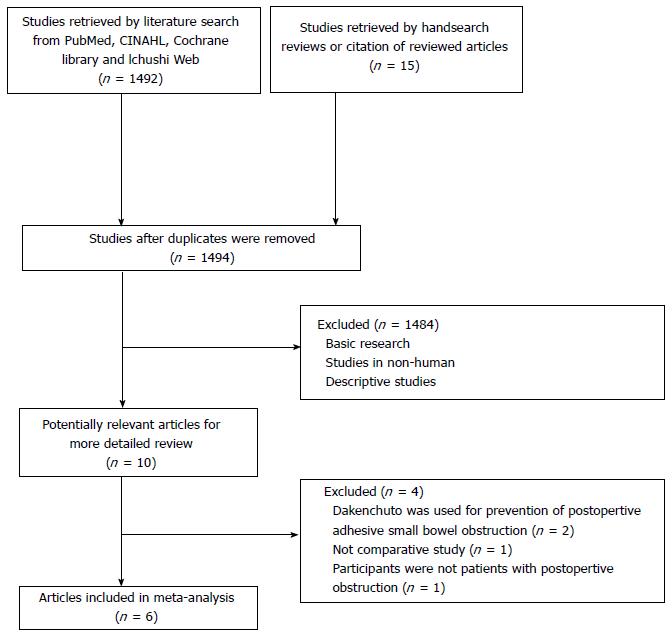

The search strategy yielded 1507 articles (Figure 1). After duplications were removed, we checked the title and abstract of the articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full texts of the remaining articles were read, and three RCTs[23-25] and three cohort studies[26-28] were chosen based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, the data were extracted from the studies (Table 1).

| Ref. | Year | Country | Study design | Dose (g) | No. of patients with Daikenchuto (surgery: No surgery) | No. of patients without Daikenchuto (surgery: No surgery) | OR (95%CI) |

| Oyabu et al[23] | 1995 | Japan | RCT | 15 | 1:27 | 5:20 | 0.15 (0.02-1.37) |

| Kubo et al[24] | 1995 | Japan | RCT | 15 | 1:17 | 2:10 | 0.29 (0.02-3.67) |

| Itohet al[25] | 2002 | Japan | RCT | 15 | 5:8 | 10:1 | 0.06 (0.01-0.65) |

| Moriwaki et al[26] | 1992 | Japan | Retrospective cohort | 15 | 1:23 | 49:154 | 0.14 (0.02-1.04) |

| Furukawa et al[27] | 1995 | Japan | Retrospective cohort | 7.5-15.0 | 6:20 | 26:49 | 0.57 (0.20-1.58) |

| Yasunaga et al[28] | 2011 | Japan | Retrospective cohort | Not mentioned | 20:124 | 28:116 | 0.67 (0.36-1.25) |

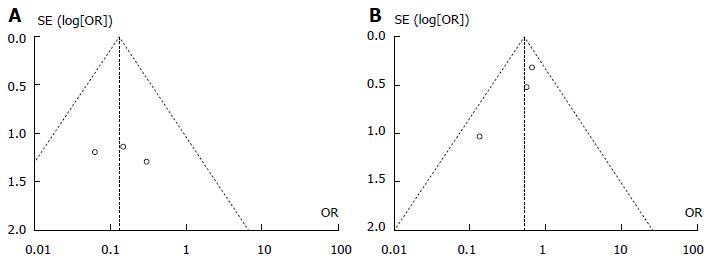

The publication year ranged from 1992 to 2011, and all research was conducted in Japan. All studies compared patients who were administered Daikenchuto with patients who were not administered Daikenchuto. The dosage of Daikenchuto was 15.0 g in four studies[23-26], 7.5-15.0 g in one study[27], and unreported in one study[28]. Daikenchuto was administered orally in one study[25], through a tube in three studies[23,24,28], or both in one study[26]. Participants were chosen regardless of the kind of abdominal surgical history in five studies[23-27], whereas only patients with a history of colorectal cancer were chosen in one study[28]. None of the included studies described the criteria of diagnosis of ASBO or pre-defined decision process for proceeding to surgery. The funnel plot of publication bias is shown in Figure 2.

Among the three RCTs, one was conducted at multiple hospitals[24], and the other two were conducted at one hospital[23,25]. In two RCTs[23,24], patients were randomly assigned using a concealed envelope, and in a third study[25], the method of assignment was not described. None of these articles mentioned the method of blinding. Patient follow-up continued until the obstruction was released and symptoms were relieved or until the patient underwent a surgery to remove the obstruction. In one trial[23], the reasons for the surgical intervention were retrospectively explained, but no explanation was provided in the other two studies[24,25]. An intention-to-treat analysis was not used in one study[24] (Table 2).

| Oyabu et al[23] | Kubo et al [24] | Itoh et al [25] | |

| 1 Was the assignment of patients to treatments randomized? | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 And if so, was the randomization list concealed (blinded or masked) to those deciding on patient eligibility for the study? | Y | Y | - |

| 3 Were all patients analysed in the groups to which they were randomized (was an “intention to treat” analysis used)? | Y | N | Y |

| 4 Were patients in the treatment and control groups similar with respect to known prognostic factors? | Y | Y | Y |

| 5 Were patients, clinicians and outcome assessors kept “blind” to which treatment was being received? | - | - | - |

| 6 Was follow-up complete? | Y | Y | Y |

Of the three retrospective cohort studies, one was conducted using a national inpatient database using propensity score analysis[28], and both the exposure and control groups were recruited at one or several hospitals in a community[26,27]. Regarding outcome domains, the criteria for the decisions to proceed to surgery for the ASBO were not described in any of the three studies (Table 3).

| Moriwaki et al[26] | Furukawa et al [27] | Yasunaga et al [28] | |

| Selection | |||

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Y | ||

| Selection of non-exposed cohort | Y | Y | Y |

| Ascertainment of exposure | Y | Y | Y |

| Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Y | Y | Y |

| Comparability | |||

| Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Y | Y | Y |

| Outcome | |||

| Assessment of outcome | |||

| Was follow-up long enough to occur | Y | Y | Y |

| Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | Y | Y | Y |

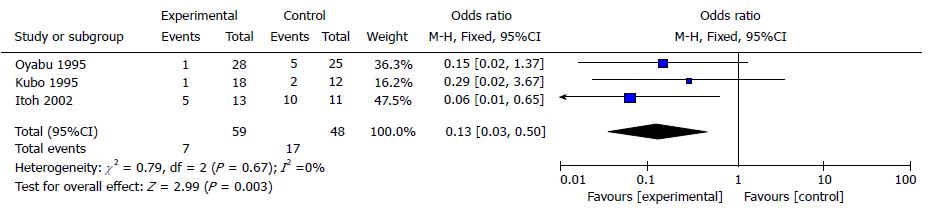

A total of 107 patients were included in the three RCTs (Figure 3). In the Daikenchuto group, seven of 59 (11.9%) patients eventually underwent surgery for the ASBO, whereas 17 of 48 (35.4%) patients underwent surgery in the control group. The overall OR was 0.13 (95%CI: 0.03-0.50), demonstrating statistical significance. There was no heterogeneity among the trials (I2 = 0%).

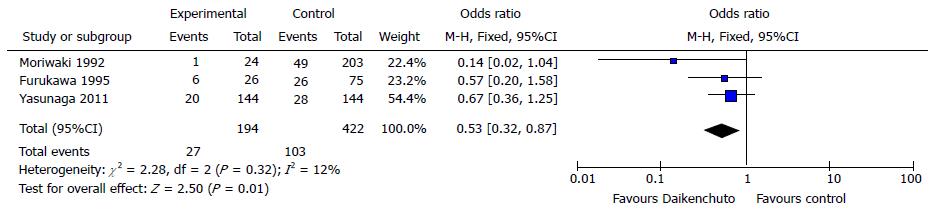

A total of 616 patients were included in the three cohort studies (Figure 4). The incidences of surgical intervention were 27 of 194 (13.9%) in the Daikenchuto group and 103 of 422 (24.4%) in the control group. The overall OR was 0.53 (95%CI: 0.32-0.87), also demonstrating statistical significance. There was low heterogeneity among the trials (I2 = 12%).

Mortality was described in the one cohort study with a total of 288 patients[28]. The number of deaths identified was four (2.8%) in the Daikenchuto group and two (1.4%) in the control group, and this difference was not found to be significant.

Length of hospital stay was described in two studies. One RCT[27] showed that the length of the hospital stay was 5.90 d shorter (95%CI: 4.77-7.03) in the Daikenchuto group. Also, one cohort study[28] showed statistical significance in favor of the Daikenchuto group using Kaplan-Meier methods and log-rank test (P = 0.018).

This systematic review provides evidence from three RCTs and three cohort studies conducted in Japan concerning the effectiveness of the traditional herbal medicine Daikenchuto in reducing the risk of surgery for patients with postoperative ASBO. From the synthesized results, ASBO patients who received Daikenchuto had a significantly lower risk of surgery. The study assessed RCTs and cohort studies individually, and they provided consistent results.

There are several treatment options recommended in guidelines for ASBO[3]. Among the options, water-soluble contrast agent administration is highly recommended because there is robust evidence for its efficacy both in predicting a need for surgery and for preventing surgery[9]. However, despite its established efficacy, 20.8% of ASBO patients treated this way proceed to surgery[9]. Daikenchuto has widely been used in Japan and has a low risk of side effects[29], and the cost is only 145.5 JPY (US$1.25) per day. From these perspectives, Daikenchuto could be used as part of initial non-operative management adjunct to water-soluble contrast administration. It is potentially useful for patients who have a high risk of anaphylactoid reaction to water-soluble contrast agent or patients who cannot tolerate surgery.

Traditional Japanese herbal medicine is known as Kampo medicine. Kampo medicine has its roots in traditional Chinese medicine and was introduced to Japan in the middle of the sixth century. The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has officially approved 212 types of Kampo medicines, and these medicines are covered by the National Health Insurance programme[30]. All certified medical doctors can prescribe both Western and Kampo medicines, and they choose the optimal one depending on the condition of the patients. Kampo medicine is referred to as an alternative medicine, but in practice, Japanese physicians use both Western medicine and Kampo medicine; in particular, Kampo medicine is commonly used for patients with medically unexplained symptoms that Western medicine often fails to solve[10]. The mechanism of the pharmacological effect is becoming clear, but more clinical research is needed before Kampo medicine will be widely adopted in other countries.

This study has several limitations. First, the included studies have methodological problems. None of included three RCTs described the blinding of clinicians and assessors. Also, none of the included studies described the criteria of decisions of proceeding to surgery. Since the decision to proceed to surgery can be subjective, there may be bias in this outcome statistic, especially when clinicians were not blinded.

Second, the reviewed studies were conducted in Japan using Japanese populations. In three studies[23,25,26], participants were recruited at one hospital. These facts pose the question of generalizability. Thus, additional evidence is needed from patients in other countries.

Finally, all studies included compared those patients who were administered Daikenchuto and who were not. We could not find studies that compared Daikenchuto and water-soluble contrast agent. Since administering water-soluble contrast agent is the standard of care, Daikenchuto and water-soluble contrast agent should be directly compared before it is applied to clinical practice.

The traditional herbal medicine Daikenchuto significantly reduces the risk of surgery for patients with postoperative ASBO in a Japanese population. In order to better generalize these results, additional studies incorporating a broader set of outcomes and an expanded population base will be needed.

We thank Alberto Gayle for his critical reading and language editing of the manuscript.

Adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO) is a common complication for patients with a history of abdominal surgery, and one fifth of them later require surgery. Daikenchuto, a traditional herbal medicine, is commonly used for postoperative adhesive small bowel obstruction, but the effectiveness of Dakenchuto in preventing surgery for patients with postoperative ASBO is not systemically assessed.

Evidence in traditional herbal medicine from clinical research, as well as basic research has increasingly been accumulated. However, the evidence is not systemically collected and integrated.

In the present study, the authors demonstrated the effectiveness of Daikenchuto for preventing patients by pooling results from randomized controlled trials and cohort studies. This is the first report of meta-analysis to assess the traditional herbal medicine, Daikenchuto.

The present study allows understanding the role of Daikenchuto for patients with postoperative ASBO to prevent surgery.

It is a very interesting paper and a new approach to manage the adhesive small bowel obstruction.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fortea-Sanchis C S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Parker MC, Ellis H, Moran BJ, Thompson JN, Wilson MS, Menzies D, McGuire A, Lower AM, Hawthorn RJ, O’Briena F. Postoperative adhesions: ten-year follow-up of 12,584 patients undergoing lower abdominal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:822-829; discussion 829-830. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Stanciu D, Menzies D. The magnitude of adhesion-related problems. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9 Suppl 2:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Galati M, Smerieri N, Biffl WL, Ansaloni L, Tugnoli G, Velmahos GC, Sartelli M, Bendinelli C. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2013 update of the evidence-based guidelines from the world society of emergency surgery ASBO working group. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seror D, Feigin E, Szold A, Allweis TM, Carmon M, Nissan S, Freund HR. How conservatively can postoperative small bowel obstruction be treated? Am J Surg. 1993;165:121-125; discussion 125-126. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Abbas SM, Bissett IP, Parry BR. Meta-analysis of oral water-soluble contrast agent in the management of adhesive small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2007;94:404-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen SC, Yen ZS, Lee CC, Liu YP, Chen WJ, Lai HS, Lin FY, Chen WJ. Nonsurgical management of partial adhesive small-bowel obstruction with oral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2005;173:1165-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ambiru S, Furuyama N, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Yoshidome H, Miyazaki M, Ochiai T. Effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on patients with adhesive intestinal obstruction associated with abdominal surgery who have failed to respond to more than 7 days of conservative treatment. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:491-495. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Branco BC, Barmparas G, Schnüriger B, Inaba K, Chan LS, Demetriades D. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic and therapeutic role of water-soluble contrast agent in adhesive small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2010;97:470-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tominaga K, Arakawa T. Kampo medicines for gastrointestinal tract disorders: a review of basic science and clinical evidence and their future application. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:452-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nakamura T, Sakai A, Isogami I, Noda K, Ueno K, Yano S. Abatement of morphine-induced slowing in gastrointestinal transit by Dai-kenchu-to, a traditional Japanese herbal medicine. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2002;88:217-221. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ohya T, Usui Y, Arii S, Iwai T, Susumu T. Effect of dai-kenchu-to on obstructive bowel disease in children. Am J Chin Med. 2003;31:129-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iwai N, Kume Y, Kimura O, Ono S, Aoi S, Tsuda T. Effects of herbal medicine Dai-Kenchu-to on anorectal function in children with severe constipation. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2007;17:115-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shimada M, Morine Y, Nagano H, Hatano E, Kaiho T, Miyazaki M, Kono T, Kamiyama T, Morita S, Sakamoto J. Effect of TU-100, a traditional Japanese medicine, administered after hepatic resection in patients with liver cancer: a multi-center, phase III trial (JFMC40-1001). Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:95-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kono T, Kanematsu T, Kitajima M. Exodus of Kampo, traditional Japanese medicine, from the complementary and alternative medicines: is it time yet? Surgery. 2009;146:837-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shibata C, Sasaki I, Naito H, Ueno T, Matsuno S. The herbal medicine Dai-Kenchu-Tou stimulates upper gut motility through cholinergic and 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptors in conscious dogs. Surgery. 1999;126:918-924. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yoshikawa K, Kurita N, Higashijima J, Miyatani T, Miyamoto H, Nishioka M, Shimada M. Kampo medicine “Dai-kenchu-to” prevents bacterial translocation in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1824-1831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65-W94. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Available from: http://www.csh.org.tw/into/medline/WORD.pdf. |

| 20. | Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/home.asp. |

| 21. | ManteL N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719-748. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46497] [Article Influence: 2113.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 23. | Oyabu H, Matsuda S, Kurisu S, Hatta K, Koyama T, Kita Y, Umeki M, Kihana E, Miyamoto K, Otaki Y. A randomized control trial for effectiveness of Daikenchuto in patinets with postoperative adhesive small bowel obstruction. Prog Med. 1995;15:1954-1958. |

| 24. | Kubo N, Uchida Y, Akiyoshi T, Miyahara M, Shibata Y, Nakano S. Effect of Daikenchuto on bowel obstruction. Prog Med. 1995;15:1962-1967. |

| 25. | Itoh T, Yamakawa J, Mai M, Yamaguchi N, Kanda T. The effect of the herbal medicine dai-kenchu-to on post-operative ileus. J Int Med Res. 2002;30:428-432. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Moriwaki Y, Yamamoto T, Katamura H, Sugiyama M. Clinical Resarch of the Effect of Dai-Kenchuto for Simple Intestinal Obstruction. Kampo Med. 1992;43:303-308. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Furukawa Y, Siga Y, Hanyu N, Hahimoto N, Mukai H, Nishikawa K, Aoki H. The effect of Daikenchuto on intestinal motility and on the treatment of postoperative bowel obstruction. Japanese J Gastroent Surg. 1995;28:956-960. |

| 28. | Yasunaga H, Miyata H, Horiguchi H, Kuwabara K, Hashimoto H, Matsuda S. Effect of the Japanese herbal kampo medicine dai-kenchu-to on postoperative adhesive small bowel obstruction requiring long-tube decompression: a propensity score analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:264289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Suzuki H, Inadomi JM, Hibi T. Japanese herbal medicine in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:688-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Okamoto H, Iyo M, Ueda K, Han C, Hirasaki Y, Namiki T. Yokukan-san: a review of the evidence for use of this Kampo herbal formula in dementia and psychiatric conditions. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1727-1742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |