Published online Jun 26, 2016. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v4.i3.63

Peer-review started: April 6, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Revised: May 20, 2016

Accepted: June 1, 2016

Article in press: June 3, 2016

Published online: June 26, 2016

Processing time: 74 Days and 21.3 Hours

AIM: To analyze the consistency of a potential involvement of the bacterium infection in the asthma disease.

METHODS: A systematic literature search of the terms “Helicobacter pylori” (H. pylori) associated to “asthma” using PubMed, Scopus and the Cochrane Library Central was performed. Reference lists from published articles were also employed. Titles of these publications and their abstracts were scanned in order to eliminate duplicates and irrelevant articles. The criteria of inclusion of the studies were: Original studies; the H. pylori diagnostic method has been declared; all ranges of age have been included in our study; a definitive diagnosis of asthma has been reported.

RESULTS: We selected 14 articles in which the association between the two conditions was addressed. In 7 studies the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the asthma population and in the control population was made explicit. There was heterogeneity between the studies (Cohran’s Q = 0.02). The H. pylori infection in the asthma population resulted 33.6% (518 of 1542), while in the control population resulted 37.6% (2746 of 7310) (relative risk of H. pylori infection in the asthma population = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.72-1.05, P = 0.015, random effects model). Instead, considering the more virulent strains, the majority of studies showed an inverse relationship between the prevalence of H. pylori infection and asthma.

CONCLUSION: In our meta-analysis the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the asthma population resulted not statistically significant lower than in control population (P = 0.15). Instead, considering the more virulent strains, the majority of studies showed an inverse relationship between the prevalence of H. pylori infection and asthma.

Core tip: The relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and asthma is an important issue, since it could influence the choice of treatment. In our meta-analysis the prevalence of the infection in the asthma population resulted not statistically significant lower than in control population.

- Citation: Ribaldone DG, Fagoonee S, Colombini J, Saracco G, Astegiano M, Pellicano R. Helicobacter pylori infection and asthma: Is there a direct or an inverse association? A meta-analysis. World J Meta-Anal 2016; 4(3): 63-68

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v4/i3/63.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v4.i3.63

Asthma is a common respiratory disease, manifested by inflammatory and obstructive processes, secondary to multiple stimuli[1].

The etiology of asthma remains largely unclear. In the latest decades the prevalence of allergic asthma increased in children[2]. The reason is unknown. Changes in personal or maternal smoking habits, types of dwelling, adaptation to Western dietary habits, less infections, as a consequence of vaccinations, decreased family size and hygiene[3], air pollution, work exposure or changed microbiota due to occidental style of life[4] might be possible causes[5]. Some infectious agents, that affect specific organs, can also cause systemic diseases. Hence, it has been postulated that infections drive the differentiation of T helper (Th) cells to the Th1 subtype with resulting suppression of the Th2 subtype, involved in IgE-mediated allergy[3,6]. However, the theory that some infections in early childhood may prevent atopic sensitization (the “hygiene hypothesis”)[7] is hotly debated[8].

The Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a gram-negative, spiral shape, mobile, microaerophilic bacillus[9] that we can find in all over the world[10]. The H. pylori infection is chronic and the humans are infected in the first 10 years of age, especially in children living in family with a low socio-economic status. In the latest two decades links between H. pylori infection and extragastric manifestations have been reported[11]. The diseases in which a possible role of H. pylori has been hypnotized are cardiovascular diseases, hepatic diseases, skin diseases, rheumatologic diseases, blood diseases, etc[12,13].

The present review attempts to highlight the data regarding a potential link between H. pylori and asthma[14].

PRISMA statement guidelines were followed for conducting and reporting meta-analysis data[15]. PICOS scheme was followed for reporting inclusion criteria.

A MEDLINE, Scopus and the Cochrane Library Central query “Helicobacter pylori” or “Helicobacter” and “asthma” was performed. Reference lists from published articles were also employed. Titles of these publications and their abstracts were scanned in order to eliminate duplicates and irrelevant articles. The last access was dated March 12, 2016. Articles not in English were read by a specific native speaker.

The criteria of inclusion of the studies were: (1) original studies; (2) the H. pylori diagnostic method has been declared; (3) all ranges of age have been included in our study; and (4) a definitive diagnosis of asthma has been reported.

Two authors (Fagoonee S and Colombini J) independently reviewed the literature search results and selected relevant studies. The full-text studies were assessed by the two authors to determine whether the inclusion criteria were met[16].

The quality of each study was defined on the basis of the following criteria: (1) selection of patients and controls; (2) methods used to diagnose H. pylori infection; (3) diagnostic method of respiratory disease; (4) type of statistical analyses performed; and (5) adjustment for confounding factors. Data abstraction and an estimate of the quality were performed independently by all the authors, who compared the results and then reached a consensus. Assessment was not blind to names and origins of the authors or publications.

A meta-analysis has been performed of the studies in which the percentage of H. pylori infection in the asthma population and in the control population was made explicit.

When heterogeneity was present the random effects model was preferred to the fixed effects model. Cohran’s Q was used to test the heterogeneity and a P value < 0.1 was used as a cut-off for significance.

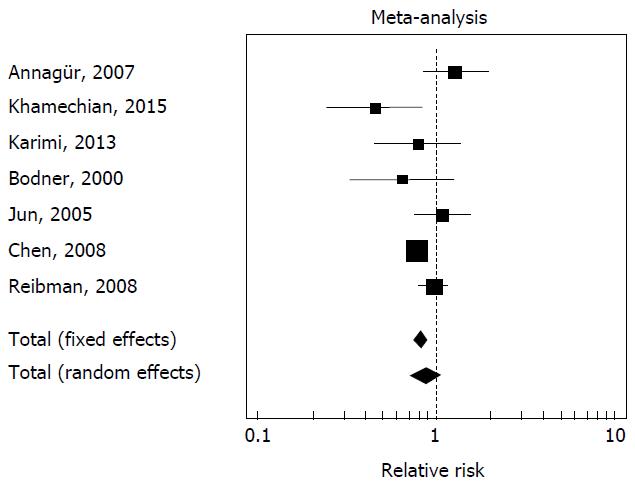

The results of the different studies, with 95%CI, and the overall effect with 95%CI, were illustrated in a forest plot graph; the pooled effects have been represented using a diamond.

A Freeman-Tukey transformation was used to calculate the weighted summary “proportion”. The Mantel-Haenszel method was used for calculating the weighted pooled “relative risk”. Statistical analyses were conducted using Med Calc® version 14.8.1 software. The statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

The search identified 169 publications. We read the abstracts of all articles and selected the 14 original papers where the inclusion criteria were met.

Pediatric population: Five studies included children with diagnosed asthma (Table 1) and in one study was described children with wheezing but not with a clear diagnosis of asthma: (1) in a monocentric, sample size: 115 participants (79 cases), follow-up: 24 mo, case-control study (quality: 3/5) on a pediatric population, the authors found no positive correlation between IgM and IgG antibodies to H. pylori and acute exacerbation or stable asthma (P = 0.494 and P = 0.227 respectively)[17]; (2) in a monocentric, sample size: 6959 participants (578 cases), follow-up: 24 mo, observational study, performed using the 13C-urea breath test (UBT) (quality: 5/5), an inverse association between H. pylori and pediatric asthma was found (OR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.66-0.94). In this case, a diagnosis was searched in the medical records, thus minimizing familial biases[18]; (3) in a monocentric[19], sample size: 300 participants (38 cases), observational study, performed using biopsy samples (quality: 4/5), an inverse association between H. pylori and pediatric asthma was demonstrated (P < 0.005).

| Ref. | Method for assessing H. pylori infection | Association | No. of asthmatic/No. of control | Age | Quality |

| Annagür et al[17] | Serological | Seropositivity was similar in acute exacerbations and stable asthmatics | 79/36 | 5-15 | 3/5 |

| Zevit et al[18] | 13C-urea breath test | Inverse association between H. pylori and pediatric asthma | 578/6381 | 5-18 | 5/5 |

| Khamechian et al[19] | Biopsy samples | Inverse association between H. pylori and pediatric asthma | 36/264 | 5-18 | 4/5 |

| Karimi et al[20] | 13C-urea breath test | Similar prevalence in cases and controls | 98/98 | < 18 | 2/5 |

| den Hollander et al[4] | Serological | Positive association between H. pylori CagA- and pediatric asthma | 3062/0 | 6 | 3/5 |

These results were not confirmed by two monocentric studies: (4) an Iranian study[20], sample size: 196 participants, follow-up: 13 mo, cross-sectional study (quality: 2/5) performed in 98 asthmatic Iranian children, that found a similar H. pylori prevalence in cases and controls; and (5) an European study[4], sample size: 3797, prospective (quality: 3/5) performed in 3062 children, was found an association between H. pylori and risk of asthma (OR = 1.75, 95%CI: 1.07-2.87); children infected by CagA- H. pylori strain had an increased risk of asthma (OR = 2.11, 95%CI: 1.23-3.60), while those affected by a CagA-positive strains were not (OR = 0.94, 95%CI: 0.32-2.79).

Moreover, a lower H. pylori infection rate in children with wheezing was found in Dutch children who participated in the allergy cohort study[21].

Adult population: Nine selected studies included adults (Table 2). All were conducted using serology to demonstrate H. pylori infection.

| Ref. | Method for assessing H. pylori infection | Association | No. of asthmatic/No. of control | Age | Quality |

| Bodner et al[3] | Serological | Seropositivity was similar in cases and controls | 19/190 | 39-45 | 3/5 |

| Tsang et al[22] | Serological | Seropositivity was similar in cases and controls | 90/97 | 42.6 ± 16 | 2/5 |

| Jun et al[14] | Serological | Seropositivity was similar in cases and controls (also for CagA) | 46/48 | 51.2 ± 12.4 | 2/5 |

| Chen et al[23] | Serological | H. pylori+ CagA+ were less likely to have ever been diagnosed as having asthma | 525/7058 | Adults | 3/5 |

| Chen et al[24] | Serological | Statistical significance only in age 3-13 yr | 946/6466 | ≥ 3 | 3/5 |

| Reibma et al[25] | Serological | H. pylori+ CagA+ were less likely to have ever been diagnosed as having asthma | 318/208 | 18-64 | 3/5 |

| Shiotani et al[26] | Serological | Seropositivity was similar in cases and controls | 6/771 | New university students | 2/3 |

| Fullerton et al[27] | Serological | Seropositivity was similar in cases and controls | 62/151 | 44.6 ± 13.5 | 3/5 |

| Lim et al[28] | Serological | Statistical significance only in age < 40 yr | 359/14673 | 18-91 | 3/5 |

Two studies: (1) one performed in Scotland[3] (monocentric, sample size: 219 participants, 19 cases), follow-up: 360 mo, survey study) (quality: 3/5); (2) another in Hong Kong[22] (monocentric, sample size: 187 participants (90 cases), follow-up: 12 mo, observational study) (quality: 2/5), indicated that exposures to H. pylori was not linked with the development of asthma in adulthood; (3) in a Japanese group of hospitalized patients, Jun et al[14] (monocentric, sample size: 94 participants, 46 cases, follow-up: 13 mo, case-control study) (quality: 2/5) did not find difference in anti-H. pylori IgG seropositivity and in CagA IgG seropositivity between asthmatics and controls (socioeconomically-matched); (4) Chen et al[23] (follow-up: 72 mo, survey study) (quality: 3/5) included 7663 participants in which information on demographics and medical history of asthma was collected using in-person interviews and valid serologic testing for H. pylori. In patients infected with H. pylori-CagA+ strains the prevalence of asthma were lower compared to uninfected subjects. Colonization by H. pylori-CagA+ strains was inversely related to having had asthma only in patients with an age of 42 year of more younger and was also find an inverse association between childhood asthma and CagA+ status; (5) similar results were found by the same authors in a following study[24] (sample size: 7412 participants, 946 cases, survey study) (quality: 3/5). They analyzed several subclasses of ages and included only subjects in the younger subclass: H. pylori infection seemed to be a protective factor against current or past asthma (OR = 0.49, 95%CI: 0.3-0.8); (6) another group (monocentric, sample size: 526 participants, 318 cases, case-control study) (quality: 3/5) reported findings supporting data on the inverse association[25]. Only after adjustment for socio-economic status there was an inverse association between asthma and CagA+ status (OR = 0.63, 95%CI: 0.41-0.98); (7) in a Japanese study[26] monocentric, sample size: 777 participants (6 cases), follow-up: 12 mo, observational cross-sectional study (quality: 2/5), newly enrolled university students with bronchial asthma, 24-year-old or younger, were all H. pylori negative; (8) no association between H. pylori seropositivity and asthma was found in an United Kingdom monocentric, sample size: 213 participants (62 cases), follow-up: 108 mo, cross-sectional study (quality 3/5) (OR = 1.09, 95%CI: 0.77-1.54)[27]; and (9) a monocentric, retrospective Korean study[28] (quality 3/5) enrolled subjects aged ≥ 18 years who had health surveillance checkups, including the serum anti-H. pylori IgG level. This large scale study demonstrated an inverse relationship between H. pylori infection and asthma among adults < 40 years old.

In seven of the fourteen studies[3,14,17,19,20,24,25] has been reported both the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the asthma population and in the control population. There is heterogeneity between the studies (Cohran’s Q = 0.02). The prevalence of H. pylori infection in the asthma population resulted 33.6% (518 of 1542), while the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the control population resulted 37.6% (2746 of 7310) (relative risk of H. pylori infection in the asthma population = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.72-1.05, P = 0.15, random effects model), difference not statistically significant. The forest plot is illustrated in Figure 1.

In animal models, experimental infection with H. pylori during the neonatal period induced a protective effect against asthma[29].

In case of gastric colonization by H. pylori-CagA+ strains, mucosal Tregs are higher in number, and mucosal levels of the immunomodulatory cytokine IL-10 may be higher compared to the case of colonization by H. pylori-CagA- strains[30-38].

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) could by a trigger to asthma symptoms[39]. Microaspiration of the gastric contents into the lung damages the bronchial mucosa, which results in mucosal inflammation and bronchial hyper-responsiveness. Diffuse gastric atrophy, a consequence of H. pylori infection, especially CagA+ strains, is a protective factor against GERD[40]. Part of the lower prevalence of asthma in people affected by H. pylori infection could be justified by the lower prevalence of GERD in this patients and not by an immunologic shift to an Th2 phenotype.

Considering the available studies on the potential association between H. pylori and asthma, sources of heterogeneity can be identified.

Focusing on sample size, negative results obtained in the various studies, when a limited number of patients was examined, must be considered with caution for the possible risk of statistical ß error[41]. Another critical issue, on this matter, is represented by the fact that included populations are heterogeneous and this may have important repercussions: The differences observed could be due to an inadequate selection of the control group.

Methods for assessing H. pylori infection vary in sensitivity and specificity, which may result in misclassification of exposure to the bacteria. Focusing on methodologies employed, some may indicate a previous contact with the microorganism (serological tests) while others an infection under way (UBT, histology). Both kinds are useful when studying long-term processes in which the microorganism could have been the primum movens and its disappearance does not change the illness story. On the contrary, if its role in an acute attack is studied, it is more appropriate to search for the active infection.

In summary, in our meta-analysis a sample of 8852 subjects are included and the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the asthma population resulted not statistically significant lower than in control population (relative risk = 0.87, P = 0.15).

The potential association between H. pylori infection and the reduction of risk of asthma development is an important issue in medicine, since it could influence the choice of bacterial treatment. The presence of H. pylori might be beneficial in childhood (decreasing risk of allergic diseases) but more deleterious later in life (increasing the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma).

Further prospective longitudinal studies with UBT for diagnosis of H. pylori are needed to prove a link between the lower prevalence of H. pylori infection and higher incidence of asthma.

Asthma is a common respiratory disease, manifested by inflammatory and obstructive processes, secondary to multiple stimuli. The etiology of asthma remains largely unclear. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a chronic one, generally acquired during childhood, and associated with lower socio-economic status.

In the latest two decades, several studies have reported potential links between chronic H. pylori infection and a variety of extragastric manifestations. These include ischemic heart disease, liver diseases, skin diseases, rheumatic diseases, blood disorders, and others.

The present review attempts to highlight the data regarding a potential correlation between H. pylori infection and asthma.

The potential association between H. pylori infection and the reduction of risk of asthma development is an important issue in medicine, since it could influence the choice of bacterial treatment.

This is a well written meta-analysis paper concerning the elucidation of a potential involvement of H. pylori infection in the pathogenesis of asthma based on analysis of 14 papers selected from 169 publications.

P- Reviewer: Abadi ATB, Nakajima N, Slomiany BL, Tosetti C, Tovey FI, Vorobjova T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Bell MC, Busse WW. Severe asthma: an expanding and mounting clinical challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:110-121; quiz 122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Omran M, Russell G. Continuing increase in respiratory symptoms and atopy in Aberdeen schoolchildren. BMJ. 1996;312:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bodner C, Anderson WJ, Reid TS, Godden DJ. Childhood exposure to infection and risk of adult onset wheeze and atopy. Thorax. 2000;55:383-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | den Hollander WJ, Sonnenschein-van der Voort AM, Holster IL, de Jongste JC, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Perez-Perez GI, Moll HA, Blaser MJ, Duijts L. Helicobacter pylori in children with asthmatic conditions at school age, and their mothers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Matricardi PM, Rosmini F, Ferrigno L, Nisini R, Rapicetta M, Chionne P, Stroffolini T, Pasquini P, D’Amelio R. Cross sectional retrospective study of prevalence of atopy among Italian military students with antibodies against hepatitis A virus. BMJ. 1997;314:999-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Romagnani S. Human TH1 and TH2 subsets: regulation of differentiation and role in protection and immunopathology. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1992;98:279-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Roussos A, Philippou N, Gourgoulianis KI. Helicobacter pylori infection and respiratory diseases: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:5-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Thomas JE, Dale A, Harding M, Coward WA, Cole TJ, Weaver LT. Helicobacter pylori colonization in early life. Pediatr Res. 1999;45:218-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Durazzo M, Rosina F, Premoli A, Morello E, Fagoonee S, Innarella R, Solerio E, Pellicano R, Rizzetto M. Lack of association between seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and primary biliary cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3179-3181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marietti M, Gasbarrini A, Saracco G, Pellicano R. Helicobacter pylori infection and diabetes mellitus: the 2013 state of art. Panminerva Med. 2013;55:277-281. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Pellicano R, Franceschi F, Saracco G, Fagoonee S, Roccarina D, Gasbarrini A. Helicobacters and extragastric diseases. Helicobacter. 2009;14 Suppl 1:58-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jun ZJ, Lei Y, Shimizu Y, Dobashi K, Mori M. Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in patients with mild asthma. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005;207:287-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11206] [Cited by in RCA: 11036] [Article Influence: 689.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Miao XP, Li JS, Ouyang Q, Hu RW, Zhang Y, Li HY. Tolerability of selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors used for the treatment of rheumatological manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:CD007744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Annagür A, Kendirli SG, Yilmaz M, Altintas DU, Inal A. Is there any relationship between asthma and asthma attack in children and atypical bacterial infections; Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Helicobacter pylori. J Trop Pediatr. 2007;53:313-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zevit N, Balicer RD, Cohen HA, Karsh D, Niv Y, Shamir R. Inverse association between Helicobacter pylori and pediatric asthma in a high-prevalence population. Helicobacter. 2012;17:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Khamechian T, Movahedian AH, Ebrahimi Eskandari G, Heidarzadeh Arani M, Mohammadi A. Evaluation of the Correlation Between Childhood Asthma and Helicobacter pylori in Kashan. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2015;8:e17842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Karimi A, Fakhimi-Derakhshan K, Imanzadeh F, Rezaei M, Cavoshzadeh Z, Maham S. Helicobacter pylori infection and pediatric asthma. Iran J Microbiol. 2013;5:132-135. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Holster IL, Vila AM, Caudri D, den Hoed CM, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, de Jongste JC, Kuipers EJ. The impact of Helicobacter pylori on atopic disorders in childhood. Helicobacter. 2012;17:232-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tsang KW, Lam WK, Chan KN, Hu W, Wu A, Kwok E, Zheng L, Wong BC, Lam SK. Helicobacter pylori sero-prevalence in asthma. Respir Med. 2000;94:756-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Inverse associations of Helicobacter pylori with asthma and allergy. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:821-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori colonization is inversely associated with childhood asthma. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:553-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Reibman J, Marmor M, Filner J, Fernandez-Beros ME, Rogers L, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Asthma is inversely associated with Helicobacter pylori status in an urban population. PLoS One. 2008;3:e4060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shiotani A, Miyanishi T, Kamada T, Haruma K. Helicobacter pylori infection and allergic diseases: epidemiological study in Japanese university students. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e29-e33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fullerton D, Britton JR, Lewis SA, Pavord ID, McKeever TM, Fogarty AW. Helicobacter pylori and lung function, asthma, atopy and allergic disease--a population-based cross-sectional study in adults. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:419-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lim JH, Kim N, Lim SH, Kwon JW, Shin CM, Chang YS, Kim JS, Jung HC, Cho SH. Inverse Relationship Between Helicobacter Pylori Infection and Asthma Among Adults Younger than 40 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Arnold IC, Dehzad N, Reuter S, Martin H, Becher B, Taube C, Müller A. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents allergic asthma in mouse models through the induction of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3088-3093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F, Gasbarrini G, Pola P. Extraintestinal pathology associated with Helicobacter infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:231-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Codolo G, Mazzi P, Amedei A, Del Prete G, Berton G, D’Elios MM, de Bernard M. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori down-modulates Th2 inflammation in ovalbumin-induced allergic asthma. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2355-2363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Amedei A, Cappon A, Codolo G, Cabrelle A, Polenghi A, Benagiano M, Tasca E, Azzurri A, D’Elios MM, Del Prete G. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori promotes Th1 immune responses. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1092-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | D’Elios MM, Amedei A, Cappon A, Del Prete G, de Bernard M. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori (HP-NAP) as an immune modulating agent. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:157-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, Timans JC, Xu Y, Hunte B, Vega F, Yu N, Wang J, Singh K. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity. 2000;13:715-725. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Robinson K, Kenefeck R, Pidgeon EL, Shakib S, Patel S, Polson RJ, Zaitoun AM, Atherton JC. Helicobacter pylori-induced peptic ulcer disease is associated with inadequate regulatory T cell responses. Gut. 2008;57:1375-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Oertli M, Müller A. Helicobacter pylori targets dendritic cells to induce immune tolerance, promote persistence and confer protection against allergic asthma. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:566-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Maldonado RA, von Andrian UH. How tolerogenic dendritic cells induce regulatory T cells. Adv Immunol. 2010;108:111-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Harris PR, Wright SW, Serrano C, Riera F, Duarte I, Torres J, Peña A, Rollán A, Viviani P, Guiraldes E. Helicobacter pylori gastritis in children is associated with a regulatory T-cell response. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:491-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kahrilas PJ, Smith JA, Dicpinigaitis PV. A causal relationship between cough and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been established: a pro/con debate. Lung. 2014;192:39-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Vicari JJ, Peek RM, Falk GW, Goldblum JR, Easley KA, Schnell J, Perez-Perez GI, Halter SA, Rice TW, Blaser MJ. The seroprevalence of cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains in the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:50-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |