Published online Dec 26, 2015. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v3.i6.284

Peer-review started: June 11, 2015

First decision: August 4, 2015

Revised: September 29, 2015

Accepted: October 23, 2015

Article in press: October 27, 2015

Published online: December 26, 2015

Processing time: 198 Days and 11.2 Hours

AIM: To compare the effect of antireflux surgery with medicine in treating gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients using meta- analysis.

METHODS: MEDLINE, Embase and the Cochrane Library were searched. We only included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the effect of surgical intervention with medical therapy for GERD. Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.2 and STATA 12.0 software. RevMan 5.2 was used to assess the risk of bias and calculate the pooled effect size, while Stata 12.0 was used to evaluate publication bias and for sensitivity analysis. We evaluated the primary outcomes with GERD-/health-related quality of life in short (one to three years) and long (three to twelve years) periods of follow-up. Secondary outcomes evaluated were DeMeester scores and the percentage of time that pH < 4 to evaluate the degree of acid exposure.

RESULTS: This meta-analysis included 7 studies with 1972 patients. It showed a positive effect of antireflux surgery compared with medical treatment in terms of health-related quality of life [standardized mean difference (SMD) = 0.18; 95%CI: 0.01 to 0.34] and GERD-related quality of life (SMD = 0.35; 95%CI: 0.11 to 0.59). We also conducted the subgroup analyses based on follow-up periods and found that surgery remained more effective than medicine over the short to medium follow-up time, but the advantage of antireflux surgery probably not maintained for long time. GERD-related quality of life in the surgical group was significantly higher than medical group for the < 3 years follow-up (SMD = 0.45; 95%CI: 0.23 to 0.66); the difference was not statistically significant when the follow-up time was ≥ 3 years (SMD = 0.30; 95%CI: -0.10 to 0.69). Meta-analysis showed a statistically significant difference between the surgical group and medical group in the percentage of time that pH < 4 (SMD = 0.38; 95%CI: 0.14 to 0.61). Meta-analysis indicated a positive effect of antireflux surgery compared with medical treatment concerning DeMeester scores (SMD = 0.32; 95%CI: 0.00 to 0.65).

CONCLUSION: Although both were effective, in some respects surgical intervention was more effective than medical therapy to treat GERD when follow-up time was up to three years.

Core tip: The advantage of our study is its systematic approach to identifying all randomized controlled trials comparing surgical intervention with medical therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). We conducted the subgroup analyses based on follow-up periods and concluded that antireflux surgery may in some ways be more effective than medicine over short to medium follow-up periods, but its effect declined over time. We also completed analyses for the percentage of time pH < 4 and DeMeester scores. Both analyses favored surgery over medical treatment. However, long-term studies are still required to determine whether surgical intervention is better than medicine in treating GERD patients.

- Citation: Jiang Y, Cui WX, Wang Y, Heng D, Tan JC, Lin L. Antireflux surgery vs medical treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease: A meta-analysis. World J Meta-Anal 2015; 3(6): 284-294

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v3/i6/284.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v3.i6.284

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a highly prevalent chronic disease of the digestive system[1,2], which is resulted from the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. The disease is chronic and relapsing that can lead to a marked reduction in patients’ health-related quality of life[3].

There are two available treatments for patients to choose: medical treatment and antireflux surgery. The medical treatment of GERD usually involves long-term administration of antacid agents; proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are now the mainstay of pharmacological treatment[4]. Although PPIs are effective in the treatment of GERD, some patients (4%) continue to experience abnormal acid reflux according to 24-h pH testing in some studies[5], and up to 37% experience a relapse of symptoms during a 5-year follow-up period[6]. With these treatments, the risks of hip fracture and enteric infections are increased[7].

Antireflux surgery is an alternative to medical therapy, but has traditionally been reserved for patients with persistent symptoms despite medication[8]. Since the introduction of the laparoscopic nissen fundoplication (LNF) procedure in the early 1990s, the operation has been found to be effective and is now widely applied throughout the world[9]. In some studies fundoplication produced a therapy of reflux symptoms in up to 90% of patients. A Cochrane review from 2010 suggested that laparoscopic fundoplication surgery was more effective than medical treatment for GERD in the short follow-up period[10]. However, some risk may come along with surgery, and the long-term benefits of it remained uncertain. Since then, several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing medicine with surgery over a longer period of time have been accomplished. The present meta-analysis aimed to systematically summarize and quantify the effects of antireflux surgery and medical treatment for GERD in RCTs on health-related quality of life and GERD-related quality of life.

To identify all relevant studies, computerized searches of MEDLINE (January 1966-April 2015), Embase (January 1980-April 2015), and the Cochrane Library (January 1970-April 2015) were performed regardless of language. All relevant RCTs comparing antireflux surgery (open or laparoscopic) with medical treatment (PPIs or H2RAs) for patients with GERD were identified. In addition, reference lists in selected papers were searched manually. We also contacted authors to obtain additional data.

Two reviewers independently screened the retrieved database files and the full texts of potentially eligible studies for relevance. We used different combinations of the keywords: “GERD”“antireflux surgery, open surgery, laparoscopic fundoplication, Nissen fundoplication” and “medical treatment, PPIs, antacid, histamine receptor antagonists”. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Studies were eligible if they met the following criteria: RCTs; included individuals with GERD (over 14 years of age), whether subjectively or objectively defined, who were judged to be suitable for either medical and/or surgical management; investigated currently used laparoscopic or open antireflux surgery techniques; investigated PPIs and histamine receptor antagonists (H2RAs) as comparative medical treatment for GERD; and reported health-related quality of life with PGWBI, EQ-5D or SF-36, GERD-related quality of life with GI well-being score, REFLUX quality-of life-score, GRESS, GSRS or GRACI scores, GERD-related symptoms and adverse events.

Studies were excluded for the following criteria: Age below 14 years old; duplicate publication; language other than English; not a RCT; unable to extract data from the original literature; no reporting of relevant outcomes; no comparison of surgical with medical intervention; reporting on short-term outcomes or reporting on endoscopic fundoplication.

One of the primary measurements was the standardized mean differences (SMDs) of patients’ health-related quality of life. Another primary indicator was the SMDs of patients’ GERD-related quality of life. Secondary outcomes included DeMeester scores and the percentage of time that pH < 4 to evaluate the degree of acid exposure.

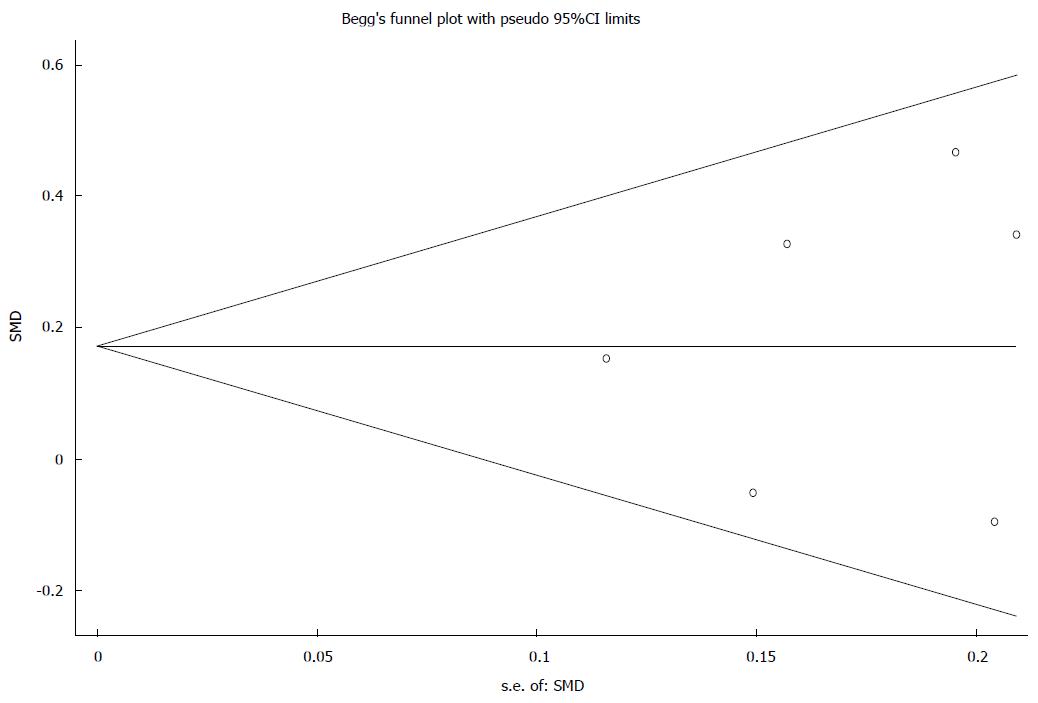

From each article, we extracted the details of authors, year of publication, country of origin, study population, sex, inclusion and exclusion criteria, type of medication, type of surgery, length of follow-up, and outcomes mentioned above independently in each arm. We assessed the risk of bias for each included study at the level of the selected outcomes. We applied Begg’s test to evaluate publication bias risk in our study[11].

Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.2 and STATA 12.0 software. RevMan 5.2 was used to assess the risk of bias and calculate the pooled effect size, while Stata 12.0 was used to assess publication bias and for sensitivity analysis.

SMDs were calculated for continuous data. Considering the different types of scores the included studies used for reporting health- or GERD-related quality of life, we calculated SMDs for pooling effect size of outcomes. The SMD was calculated by dividing the mean difference in each trial by the standard deviation. An SMD greater than 0 corresponded to a favorable effect of the surgical intervention compared with medical management; While an SMD less than 0 meant a negative effect of surgery. In some questionnaires in which higher scores equaled lower GERD-related quality of life (GSRS, GRACI, GRESS), the mean values were multiplied by -1 before calculation of the SMD. Likewise, higher DeMeester scores and the percentage of time that pH < 4 indicate worse acid control, so these two items were calculated in the same way as described above.

Outcome measures were quantitatively summarized, so we used the I2 index to analyze heterogeneity. I2 < 25% indicated that there was low heterogeneity and a fixed effect model was applied to pool effect size. If the I2 value was > 25% and < 50%, it suggested that there was moderate heterogeneity. When I2 was > 50%, it showed that there was significant heterogeneity[12]. To achieve more conservative results, a random effect model was applied in the last two situations[13]. Furthermore, subgroup analyses were performed. To identify sources of significant heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis was applied by removing individual study from the data set followed by analysis of the effect of their removal on the overall results.

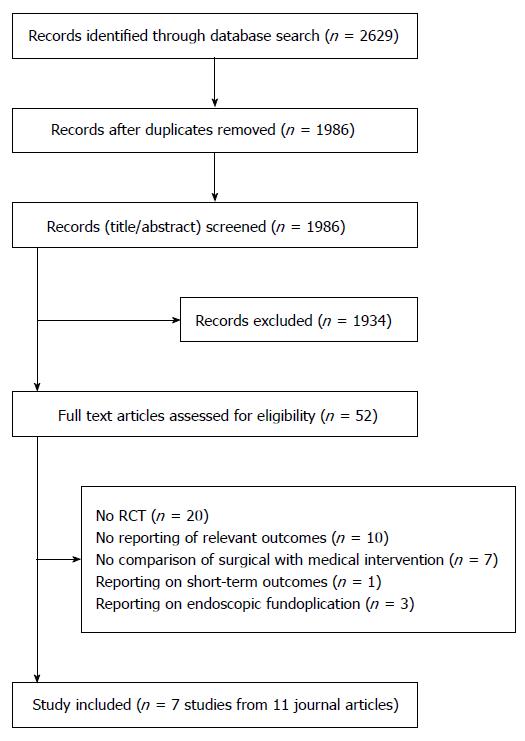

From a total of 1763 records, 11 journal articles reporting 7 studies (n = 1972) were qualified for the criteria and included in this meta-analysis[6,14-23] (Figure 1).

The 7 studies were respectively completed in the United Kingdom (3), Canada (1), and the United States (1), with multicenter investigations in 11 European countries (2) (Table 1). The studies were conducted on adults (mean age range 42-58 years across studies). All but one study[19,20] included more males than females (female/male ratio 1:0.7-1:3). The follow-up period ranged from 1-12 years in the 11 included articles. Among them, three had a follow-up period of 1 year[14,16,19], two had three years of follow-up[20,22], and the remaining studies had a follow-up period longer than 3 years. The studies included one 3-arm study and six 2-arm studies; five of them evaluated the effects of laparoscopic antireflux surgery[14-17,19,20,22,23] while two evaluated open surgery[6,18,21]. The GERD criteria in the included studies ranged from mild symptoms[22,23] to complicated GERD (Table 2). In all but one study, PPIs were used. In two studies, the response to PPI treatment was an inclusion criterion[6,18]. Participation in two additional studies required treatment with PPI for at least 1 year[17,19].

| Ref. | Group | No. of patients randomized | Mean age (yr) | Female/male | Mean follow-up years | No. of patients at follow-up | Country |

| Mahon et al[14] | LNF | 109 | 48 | 1:1.9 | 1 | 106 | United Kingdom |

| PPIs | 108 | 47 | 1:2.6 | 97 | |||

| Mehta et al[15] | LNF | 91 | 47 | 1:2.0 | 6.9 | 91 | United Kingdom |

| PPIs | 92 | 47 | 1:2.5 | 38 | |||

| Grant et al[16] | LF | 178 | 46.7 | 1:1.9 | 1 | 145 | United Kingdom |

| Best medical management(mainly PPIs) | 179 | 45.9 | 1:2.2 | 154 | |||

| Grant et al[17] | LF | 178 | 46.7 | 1:1.9 | 5 | 127 | United Kingdom |

| Best medical management(mainly PPIs) | 179 | 45.9 | 1:2.2 | 119 | |||

| Lundell et al[6] | Open antireflux surgery | 155 | 51 | 1:3.2 | 5 | 79 | Sweden |

| omeprazole | 155 | 55 | 1:3.0 | 104 | |||

| Lundell et al[18] | Open antireflux surgery | 155 | 51 | 1:3.2 | 12 | 53 | Sweden |

| omeprazole | 155 | 55 | 1:3.0 | 71 | |||

| Anvari et al[19] | LNF | 52 | 42.9 | 1:0.7 | 1 | 48 | Canada |

| PPIs | 52 | 42.1 | 1:1 | 48 | |||

| Anvari et al[20] | LNF | 52 | 42.9 | 1:0.7 | 3 | 49 | Canada |

| PPIs | 52 | 42.1 | 1:1 | 44 | |||

| Spechler et al[21] | Open Nissen fundoplication | 82 | 58 | NR | 9.1 | 38 | United States |

| Antacid and ranitidin | 77 | 58 | NR | 10.6 | 91 | ||

| Lundell et al[22] | Laparoscopic antireflux surgery | 288 | 44.8 | 1:2.2 | 3 | 204 | 11 European countries |

| Esomeprazole | 266 | 45.4 | 1:3.0 | 208 | |||

| Galmiche et al[23] | Laparoscopic antireflux surgery | 288 | 44.8 | 1:2.2 | 5 | 180 | 11 European countries |

| Esomeprazole | 266 | 45.4 | 1:3.0 | 192 |

| Ref. | Inclusion criteria | Relevant outcomes |

| Mahon et al[14] | Symptoms of GERD for at least 6 mo and pathologic reflux | PGWBI, GI well-being score, DeMeester score, pH testing |

| Mehta et al[15] | Symptoms of GERD for at least 6 mo and pathologic reflux pathologic reflux | DeMeester symptom score |

| Grant et al[16,17] | Symptoms of GERD requiring maintenance treatment with PPI (or other) for at least 12 mo, pathologic reflux | REFLUX quality-of life-score, EQ-5D, SF-36 |

| Lundell et al[6,18] | Chronic GERD with concomitant esophagitis and response to omeprazole | PGWBI, GSRS |

| Anvari et al[19,20] | Chronic GERD, PPI for at least 1 yr, pathologic reflux, symptom control | GERSS, 24 h pH monitoring, EQ-5D |

| Spechler et al[21] | Complicated GERD(abnormal acid reflux at least 1 of the 4 disorders: Barrett esophagus, peptic esophageal ulcer, peptic esophageal stricture, or erosive esophagitis) | GRACI scores, 24 h pH monitoring, SF-36 |

| Lundell et al[22] and Galmiche et al[23] | Chronic GERD, assessed through endoscopy, 24 h pH-metry and response to esomeprazole. Esophagitis no more than LA grade B, GERD symptoms no more than mild | GSRS |

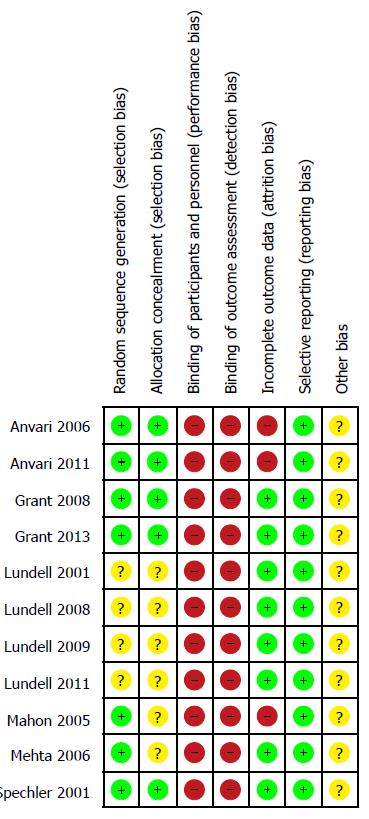

The results of the risk of bias assessment are presented in Table 3. The sequence generation for randomization was adequate in all but two studies[6,18,22,23]. Concealment of group allocation was not clear in four[6,14,15,18,22,23]. Healthcare providers and patients were not blinded in any study. Observer bias could not be excluded because none of the studies reported blinded outcome assessment. Four studies used intention-to-treat analysis to avoid attrition bias[6,15-18,21-23].

| Ref. | Sequence generation adequate | Allocation concealed | Blinding | Intention-to-treat analysis performed | Exact data available | |

| Patients | Healthcare providers | |||||

| Mahon et al[14] | Yes | Unclear | No | No | No | Yes |

| Mehta et al[15] | Yes | Unclear | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Grant et al[16,17] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Lundell et al[6,18] | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Anvari et al[19,20] | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Spechler et al[21] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Lundell et al[22] and Galmiche et al[23] | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Yes | Yes |

In the 7 studies, the individuals were analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized. Across these trials, the percentage of patients not analyzed ranged from 6% to 42% in the medical group and from 0% to 34% in the surgical group. Two studies[14,19,20] did not address the missing continuous outcome data appropriately. Figure 2 shows the summary of the risk of bias assessment for each study.

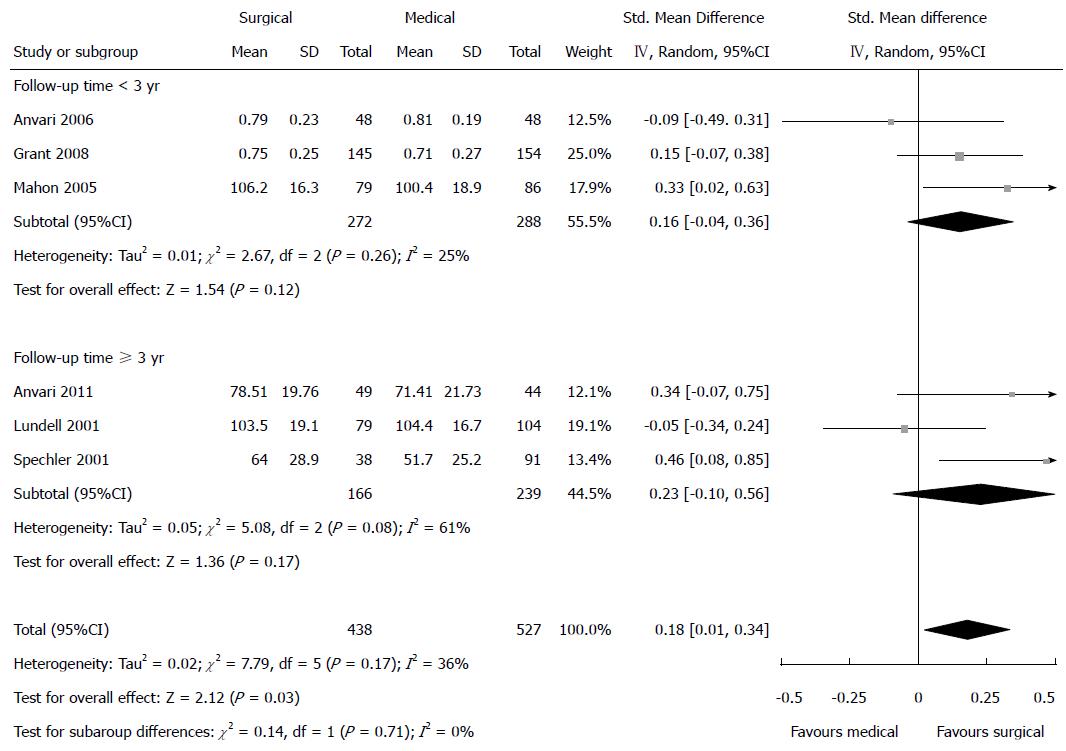

Health-related quality of life was reported in five studies. Four of them reported higher health-related quality of life in the surgical group than in the medical group, with the differences being statistically significant in 2 studies. One reported a slightly negative effect of surgery on health-related quality of life[6]. Meta-analysis favored antireflux surgery over medical treatment concerning health-related quality of life (SMD = 0.18; 95%CI: 0.01 to 0.34), with no significant heterogeneity observed (I2 = 36%; P = 0.17) (Figure 3). It is obvious that the general well-being of patients who received antireflux surgery improved.

Subgroup analyses: Health-related quality of life was reported to be higher in the surgical group than in the medical group when the follow-up period was < 3 years; but this was not significantly different (SMD = 0.16; 95%CI: -0.04 to 0.36) with no obvious heterogeneity observed (I2 = 25%; P = 0.26). Likewise, no significant difference was found between the surgical and medical group when the follow-up period was ≥ 3 years (SMD = 0.23; 95%CI: -0.10 to 0.56); in this situation the heterogeneity was high (I2 = 61%; P = 0.08) (Figure 3).

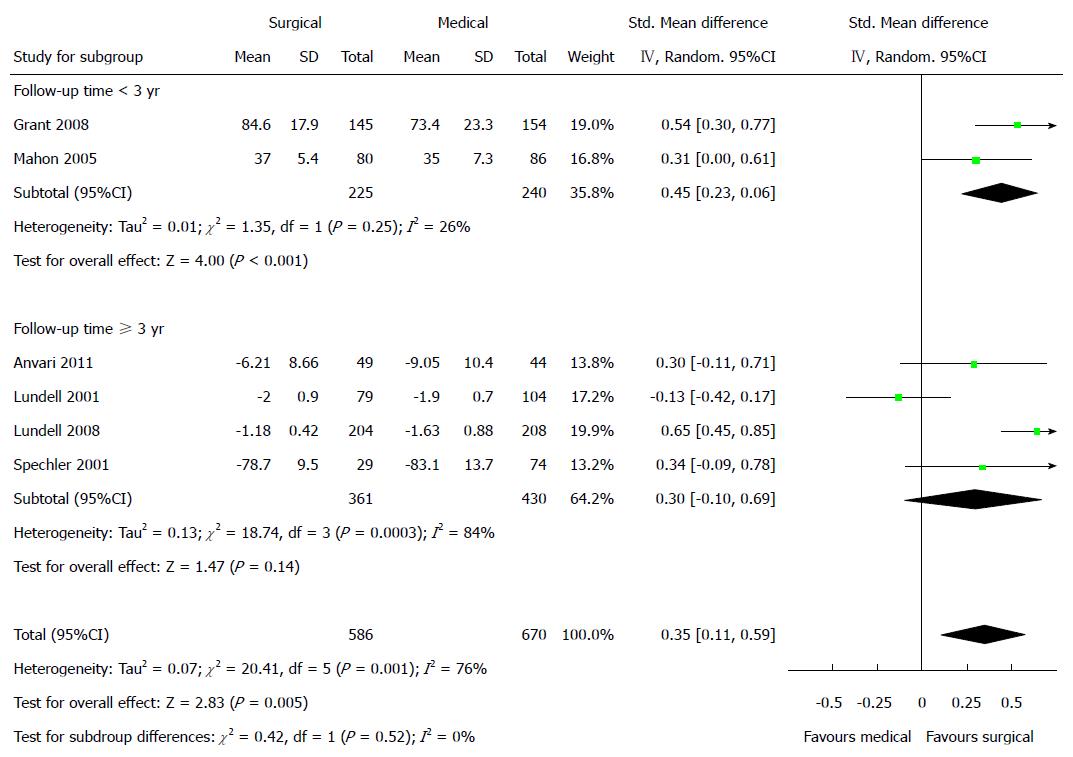

GERD-related quality of life was reported in six studies. All of them reported higher GERD-related quality of life in the surgical group than in the medical group and the differences were statistically significant in 2 studies. Meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in the two groups (SMD = 0.35; 95%CI: 0.11 to 0.59), but the heterogeneity was high (I2 = 76.0%; P = 0.001) (Figure 4). GERD-related quality of life was found to improve more in the patients who underwent surgery.

Subgroup analyses: GERD-related quality of life was significantly different between the surgical and medical groups when the follow-up period was < 3 years (SMD = 0.45; 95%CI: 0.23 to 0.66), with no significant heterogeneity observed (I2 = 26.0%; P = 0.25). The difference was not as significant when the follow-up period was ≥ 3 years (SMD = 0.30; 95%CI: -0.10 to 0.69) with significant heterogeneity observed (I2 = 84.0%; P < 0.001) (Figure 4).

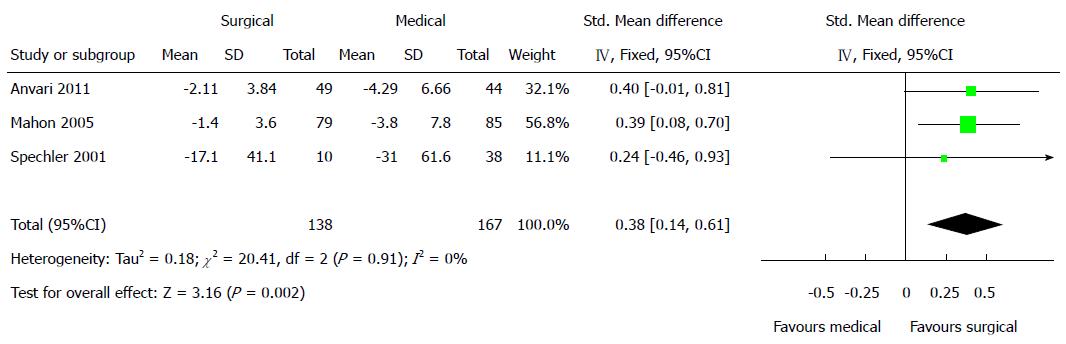

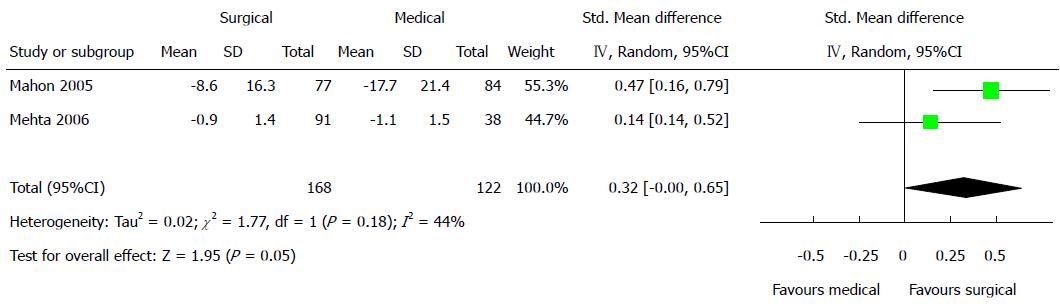

The percentage of time that pH < 4 was reported in three studies[14,19,21]. All of them reported a higher percentage of time that pH < 4 in the medical group, with one being statistically significant. Meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in this parameter (SMD = 0.38; 95%CI: 0.14 to 0.61) with no heterogeneity observed (I2 = 0%; P = 0.91) (Figure 5). It showed that antireflux surgery was better than medical treatment in controlling pH. DeMeester scores were reported in two studies[14,15]. Both of them reported lower DeMeester scores in the surgical group than in the medical group. Meta-analysis showed a better effect of antireflux surgery than medical treatment on DeMeester scores (SMD = 0.32; 95%CI: 0.00 to 0.65), the heterogeneity was not significant (I2 = 44%; P = 0.18) (Figure 6). This outcome showed the positive role of antireflux surgery in alleviating acid exposure.

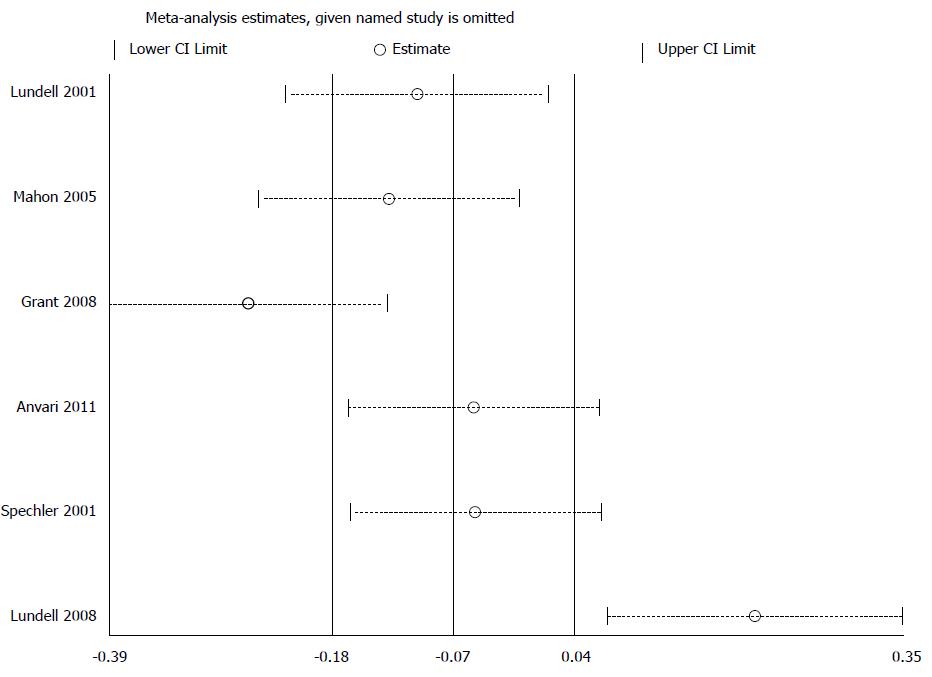

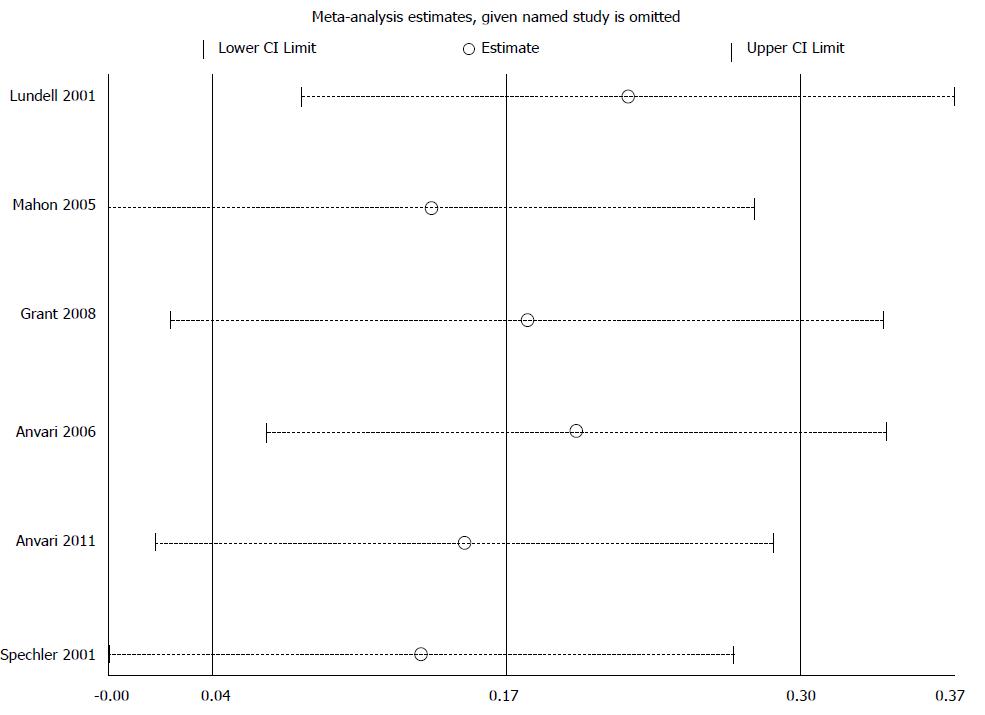

To assess whether a single study could influence the main results, we excluded each study individually to evaluate its influence on the pooled effect size and the heterogeneity of the main results. When analyzing GERD-related quality of life, exclusion of the study of Grant et al[16] and Lundell et al[22] resulted in a loss of the statistical significance of the pooled SMD (Figure 7). Removing any individual study from the data set did not substantially influence the general health-related quality of life (Figure 8).

Funnel plot was used to assess the outcome of health-related quality of life. The P-value calculated by Begg’s test was 0.707, indicating no serious publication bias (Figure 9). However, given that the number of studies was limited, publication bias was judged as not clear[24].

This meta-analysis indicates that antireflux surgery may be more effective than medical therapy for GERD in improving health-related quality of life and GERD-related quality of life when the follow-up period was < 3 years. Antireflux surgery could also result in a lower percentage of time that pH < 4 and lower DeMeester scores.

The difference in the GERD-related quality of life is obvious for one to three years, but it declines over time. The difference was not significant in the health-related quality of life between the surgical and medical group over longer time. Therefore, the long-term sustainability of the surgical benefits is still unclear.

No perioperative or surgery-associated deaths have been reported during the follow-up period. However, one study observed a decrease in survival among the patients randomized to surgery[21], while another reported more deaths attributed to cardiac causes in the medical group[18]. The complication of dysphagia may increase after fundoplication as well, and the symptoms associated with antireflux surgery like bloating, inability to belch or vomit, and abdominal fullness were conflicting.

The advantage of this meta-analysis is its comprehensive method to identifying all RCTs comparing antireflux surgery with medical treatment for GERD. The outcome of health-related quality of life proved to be robust through a variety of sensitivity analyses.

We also conducted analyses for the percentage of time that pH < 4 and DeMeester scores. Both analyses favored surgery over medical treatment. This might indicate that the main symptoms of GERD (heartburn and regurgitation) were less frequent after surgical intervention than medical management.

Through subgroup analyses, antireflux surgery in some ways may be more effective than medicine over short to medium follow-up time, but its effect declined over time. A published meta-analysis comparing surgery with medical management using PPI or H2 receptor antagonists[25] concluded that surgical treatment is more effective than medical management, and that surgery may be considered as a treatment alternative to long-term medical therapy. However, the review did not perform subgroup analyses based on follow-up time. We did not find evidence that the advantage of antireflux surgery in effectiveness remained for long time. Because large majority of GERD patients do not experience erosive disease, given the possible adverse events associated with antireflux surgery, it should be considered only in selected GERD patients.

There are also some limitations in our study. The pooled effect sizes were just based on 7 studies. In addition, the methodological quality of 4 studies was judged as unclear allocation concealment. Two trials did not report their recruitment strategy adequately, making it possible that only a certain subgroup of the eligible patient population was included in these studies[6,18,22,23].

Our main results were based on questionnaires, which are sometimes affected by subjective factors. We could not obtain subjective values such as 24 h - pH testing, LES, and endoscopic results. The inclusion criteria of GERD in our included studies varied from mild symptoms to complicated GERD, making us unable to analyze subgroups based on the severity of GERD. Nor could we analyze GERD-related symptoms or patient satisfaction because the methods each study used were different.

Long-term acid suppression may result in some complications[26,27]. However, nowadays no specific serious adverse events have been judged to be attributable to acid suppressive treatment alone. This might be because the follow-up period was insufficient, and therefore, we couldn’t draw any conclusion concerning adverse events except for the longer period.

In two of the included studies, only PPI responders were enrolled. Due to the limited data on PPI responders and patients who initially were partially or completely refractory to PPI therapy, we presented no results stratified by it. Nevertheless, these poor responders were a heterogeneous group with lots of underlying reasons for their non-responsiveness to acid suppressive therapy[28]. The most common reason was the absence of actual reflux disease, with symptoms resulting from non-reflux conditions.

Surgery also appears to be a relatively safe option if performed by an experienced surgeon. There were few cases of intraoperative morbidity and postoperative complications reported in the studies. Recently, surgical therapy has become a option for long-term treatment in GERD patients, which is generally not recommended for patients resistant to PPI therapy[29]. In contrast, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence does not suggest surgery to the patients with persistent GERD as the routine management[30].

The outcomes of our study apply to a general population of GERD individuals over 14 years of age. In the 7 studies, the proportion of females ranged from 25% to 59%. No information was available on body mass index. The results might be different for specific subgroups.

In summary, this meta-analysis shows comprehensive evidence that open or laparoscopic antireflux surgery might be more effective than medical treatment for GERD in terms of GERD - and health-related quality of life, especially for 3 years of follow-up with GERD-related quality of life. However, the advantage of antireflux surgery in effectiveness may not remain for long time. In addition, the differences in long term adverse events between surgery and medical management remain unclear. Overall, we conclude that for most GERD patients, medical treatment may be the first choice, and that surgical intervention should be considered only after critical evaluation by experienced doctors. Further studies are warranted on this topic.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a highly prevalent chronic disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. The main treatments for GERD include medical treatment and antireflux surgery. However, the effect of medical treatment and antireflux surgery on GERD symptoms remains unclear.

Current treatment options for GERD include medical treatment and antireflux surgery. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing pharmaceutical treatment with surgery over a longer term have been completed. Worldwide research is directed at treatment options that maximize safety and effectiveness.

In the present study, the authors analyzed the effect of antireflux surgery and medical treatment for GERD by pooling results from different RCTs. They conducted subgroup analyses to investigate GERD and health-related quality of life to systematically and comprehensively evaluate the effect of the two treatments.

The present meta-analysis allows comprehensive understanding of the roles of antireflux surgery and medical treatment for GERD.

It is a good job, up to date results of medical and surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux.

P- Reviewer: Lara FJP, Skrypnyk IN S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 2. | Orlando RC. Reflux esophagitis: overview. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1995;210:36-37. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, Jones M, Kahrilas PJ, Rentz AM, Sonnenberg A, Stanghellini V, Stewart WF, Tack J. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:543-552. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-328; quiz 329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1136] [Cited by in RCA: 1120] [Article Influence: 93.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gerson LB, Boparai V, Ullah N, Triadafilopoulos G. Oesophageal and gastric pH profiles in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s oesophagus treated with proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:637-643. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, Pedersen SA, Liedman B, Hatlebakk JG, Julkonen R, Levander K, Carlsson J, Lamm M. Continued (5-year) followup of a randomized clinical study comparing antireflux surgery and omeprazole in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:172-179; discussion 172-179. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Khalili H, Huang ES, Jacobson BC, Camargo CA, Feskanich D, Chan AT. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of hip fracture in relation to dietary and lifestyle factors: a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Guidelines for surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Surg Endosc. 1998;12:186-188. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Zacharoulis D, O’Boyle CJ, Sedman PC, Brough WA, Royston CM. Laparoscopic fundoplication: a 10-year learning curve. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1662-1670. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Wileman SM, McCann S, Grant AM, Krukowski ZH, Bruce J. Medical versus surgical management for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;17:CD003243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088-1101. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [PubMed] |

| 13. | DerSimonian R, Levine RJ. Resolving discrepancies between a meta-analysis and a subsequent large controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:664-670. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Mahon D, Rhodes M, Decadt B, Hindmarsh A, Lowndes R, Beckingham I, Koo B, Newcombe RG. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication compared with proton-pump inhibitors for treatment of chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux. Br J Surg. 2005;92:695-699. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Mehta S, Bennett J, Mahon D, Rhodes M. Prospective trial of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitor therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: Seven-year follow-up. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1312-1316; discussion 1316-1317. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Grant AM, Wileman SM, Ramsay CR, Mowat NA, Krukowski ZH, Heading RC, Thursz MR, Campbell MK. Minimal access surgery compared with medical management for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: UK collaborative randomised trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Grant AM, Cotton SC, Boachie C, Ramsay CR, Krukowski ZH, Heading RC, Campbell MK. Minimal access surgery compared with medical management for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: five year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial (REFLUX). BMJ. 2013;346:f1908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, Hatlebakk JG, Wallin L, Engström C, Julkunen R, Montgomery M, Malm A, Lind T. Comparison of outcomes twelve years after antireflux surgery or omeprazole maintenance therapy for reflux esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1292-1298; quiz 1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, Armstrong D, Goeree R, Ungar W, Goldsmith C. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease: One-year follow-up. Surg Innov. 2006;13:238-249. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, Armstrong D, Goeree R, Ungar W, Goldsmith C. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for the treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): 3-year outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2547-2554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, Goyal RK, Hirano I, Ramirez F, Raufman JP, Sampliner R, Schnell T, Sontag S. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2331-2338. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Lundell L, Attwood S, Ell C, Fiocca R, Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Lind T, Junghard O. Comparing laparoscopic antireflux surgery with esomeprazole in the management of patients with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a 3-year interim analysis of the LOTUS trial. Gut. 2008;57:1207-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, Ell C, Fiocca R, Eklund S, Långström G, Lind T, Lundell L. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305:1969-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context, second edition. London: BMJ Books 2001; . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Rickenbacher N, Kötter T, Kochen MM, Scherer M, Blozik E. Fundoplication versus medical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:143-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Moayyedi P, Cranney A. Hip fracture and proton pump inhibitor therapy: balancing the evidence for benefit and harm. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2428-2431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lodato F, Azzaroli F, Turco L, Mazzella N, Buonfiglioli F, Zoli M, Mazzella G. Adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:193-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zaninotto G, Attwood SE. Surgical management of refractory gastro-oesophageal reflux. Br J Surg. 2010;97:139-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lundell L. Borderline indications and selection of gastroesophageal reflux disease patients: ‘Is surgery better than medical therapy’? Dig Dis. 2014;32:152-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | North of England Dyspepsia Guideline Development Group (UK). Dyspepsia: managing dyspepsia in adults in primary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance 2004; . [PubMed] |