Published online Feb 26, 2015. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v3.i1.36

Peer-review started: May 23, 2014

First decision: July 10, 2014

Revised: October 30, 2014

Accepted: November 17, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

Published online: February 26, 2015

Processing time: 245 Days and 2.4 Hours

AIM: To assess the efficacy and safety of antithrombotic drugs (antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs) compared to no antithrombotic treatment or placebo in patients with heart failure (HF) and sinus rhythm.

METHODS: We searched Medline and Cochrane Library for randomized controlled trials evaluating antithrombotic treatment and no antithrombotic treatment in patients with HF and sinus rhythm. Risk ratio (RR) and 95%CIs were estimated performing meta-analysis with random effects method.

RESULTS: Two studies met the inclusion criteria: Heart failure Long-term Antithrombotic Study and Warfarin/Aspirin Study in Heart failure, with 336 patients and mean follow-up 1.8-2.25 years. Stroke risk was not reduced by acetylsalicylic acid (RR = 1.18, 95%CI: 0.17-8.15), oral anticoagulation (RR = 0.30, 95%CI: 0.03-2.65) or overall antithrombotic drugs (RR = 0.52, 95%CI: 0.10-2.74). Acetylsalicylic acid showed a significant increased risk of worsening HF (RR = 1.78, 95%CI: 1.08-2.92), while oral anticoagulation had no impact in this outcome (RR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.61-1.75). Overall antithrombotic drugs showed a significant risk increase of major bleeding (RR = 6.99, 95%CI: 0.89-54.64).

CONCLUSION: Best available evidence does not support the routine use of antithrombotic drugs in patients with HF and sinus rhythm. These drugs, particularly oral anticoagulation has the hazard of increase significantly major bleeding risk.

Core tip: In patients with atrial fibrillation, chronic heart failure (CHF) increases thromboembolic risk and oral anticoagulation is essential to decrease the risk of thromboembolic complications. Evidence suggests a positive association between CHF, impaired hemostasis and thromboembolic events. Whether antithrombotic drugs should be recommended for these patients (in sinus rhythm) is still debated. We looked for the best available evidence and we found 2 studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria. We performed a meta-analysis of antithrombotic drugs vs placebo and strengthened that antithrombotic drugs do not decrease the risk of stroke (fatal or non-fatal) and increase the risk of major bleeding.

- Citation: Caldeira D, Cruz I, Calé R, Martins C, Pereira H, Ferreira JJ, Pinto FJ, Costa J. Antithrombotic treatment in chronic heart failure and sinus rhythm: Systematic review. World J Meta-Anal 2015; 3(1): 36-42

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v3/i1/36.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v3.i1.36

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is an increasingly prevalent cardiovascular disease with significant associated morbidity and mortality[1]. CHF constitutes a significant economic burden[2,3], which is expected to increase over the next decades due to increasing prevalence of associated diseases and risk factors as well as population aging. Former observational studies suggest a positive association between CHF, impaired hemostasis and thromboembolic events[4,5]. In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), CHF increases thromboembolic risk and oral anticoagulation is the cornerstone of AF treatment aiming to decrease the risk of thromboembolic complications[6]. The results from the WARCEF trial (Warfarin vs Aspirin in Reduced Cardiac Ejection Fraction) has highlighted the role of antithrombotic treatment in patients with CHF and sinus rhythm[7]. There were no differences between warfarin and acetylsalicylic acid in the primary outcome (time to the first event in a composite end point of ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, or death from any cause). However, warfarin was associated with fewer stroke events (2.5% vs 4.7%) but also with a higher rate of major bleeding events (5.8% vs 2.7%). The clinical interpretation of these findings was that the choice between warfarin and aspirin should be made on the basis of the individual patient[8].

Previous systematic reviews with meta-analyses comparing oral anticoagulation (namely warfarin) and acetylsalicylic acid in patients with CHF and sinus rhythm reached conclusions overlapping those from the WARCEF study[9-13].

Although much effort have been done comparing and discussing the relative effectiveness of oral anticoagulation vs acetylsalicylic acid in patients with CHF and sinus rhythm, significantly less is known about the true efficacy of the overall antithrombotic treatment. Therefore, we aimed to perform a systematic review to better estimate the true clinical benefit of antithrombotic treatments (oral anticoagulation or antiplatelet drugs) against placebo, standard care or no treatment, in patients with CHF and sinus rhythm.

This work followed PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses promoted by the EQUATOR network[14].

We have searched for all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating patients with CHF and sinus rhythm treated with oral antithrombotic therapy or control. We considered for antithrombotic treatments both oral anticoagulants (such as vitamin K antagonists, like warfarin, acenocoumarol or phenprocoumon) and antiplatelet drugs [such as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), clopidogrel or ticlopidine]. We allowed controls under placebo, standard care or no antithrombotic treatment. Studies had to report clinical and/or echocardiographic features for the enrolled CHF patients, such as impaired left ventricle ejection fraction or shortening fraction.

Medline and Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) databases were searched from inception to November 2013 for eligible studies. The search strategy details are available at the Online Supplementary Material. We considered all studies irrespective of language. References of obtained studies were also comprehensively searched and cross-checked to identify possible missing studies.

Citations obtained from electronic search were independently screened by two authors, followed by full-text assessment of potentially eligible studies for inclusion in accordance with previously mentioned criteria.

Primary outcome was stroke (fatal or non-fatal). Secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, worsening heart failure (HF), major bleeding and a composite of major adverse clinical events, defined as the combination of mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction and HF.

We extracted detailed data about demographics, comorbidities, interventions, follow-up and outcomes. Data extraction and data entry into software was double-checked. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

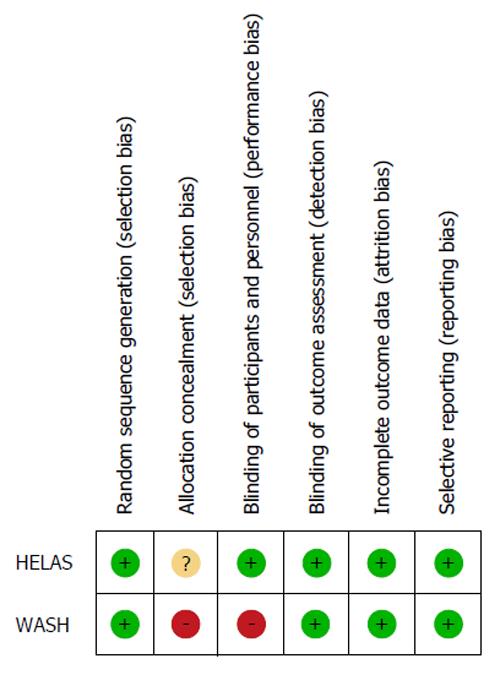

Quality of reporting was analysed by using a qualitative classification according to risk of bias (high, unclear or low risk), adapted from Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool[15]. Studies were not excluded based on quality of reporting.

Outcomes data were summarized as frequencies. Statistical analyses were performed using the RevMan version 5.2.6 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012) to derive forest plots with pooled estimates of risk ratios (RR) and their 95%CI. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with χ2 test and quantified with Higgins I2 test[16]. Pooled results estimates were based on the random or fixed effects model according to the existence (I2≥ 50%) or not (I2 < 50%) of significant heterogeneity[17]. Publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots symmetry and Peters’ regression tests[18,19]. Pooled results were evaluated for the overall antithrombotic treatment, as well separately for antiplatelet and anticoagulation groups.

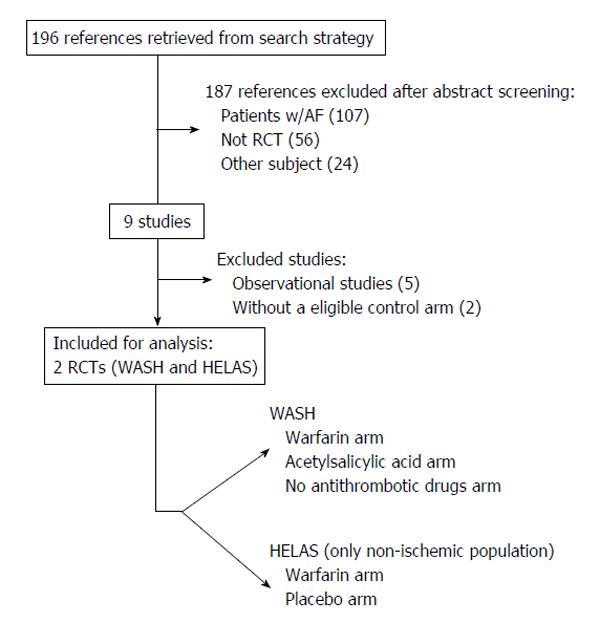

After title and abstract screening of citations obtained in Medline and Cochrane Library, 196 citations were retrieved. One-hundred and eighty seven studies did not meet inclusion criteria through initial assessment: 107 included AF patients; 56 studies were not randomized and 24 did not address the pretended topic (either different population and/or other interventions).

The remaining 9 studies were fully-evaluated, of which 7 were further excluded: 5 were observational studies, and 2 RCTs did not include a placebo, standard care or no antithrombotic treatment arm (WARCEF and WATCH trials)[5,20]. Therefore, 2 RCTs were eligible for the purpose of this systematic review[21,22]. The search of reference lists of review articles and included studies failed to identify any additional eligible study[23-27]. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of studies’ selection.

Studies Warfarin/Aspirin Study in Heart failure (WASH) and Heart failure Long-term Antithrombotic Study (HELAS) met the outlined inclusion criteria[21,22].

WASH study was an open-label RCT with blinded endpoint assessment, published in 2004. WASH enrolled 254 patients (80 warfarin; 80 ASA; 94 no anti-thrombotic treatment) with CHF and sinus rhythm and followed them for a mean period of 2.25 years. About 60% had CHF of ischemic etiology, 75% of the patients were male, mean age was 63 years old, and 30% were in New York Heart Association class III/VI. About 34% of the patients had hypertension, and 20% had diabetes. In terms of echocardiography mean parameters, patients had a fractional shortening of 15% and a left-ventricular end-diastolic diameter of 66 mm. Regarding treatments, the daily dosage of acetylsalicylic acid was 300 mg and international normalized ratio (INR) target for warfarin-treated patients was 2.5 (range 2-3). Primary outcome was the composite of all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal stroke[21].

HELAS study was published in 2006 and included two comparisons: warfarin vs acetylsalicylic acid in patients with CHF of ischemic etiology (not evaluated in this review due to absence of a placebo/no treatment control arm); and warfarin vs placebo in 82 patients (38 vs 44) with dilated non-ischemic CHF in sinus rhythm. Study’s mean follow was 1.8 years. Most of the patients were male and mean age was 55 years. Hypertension was present in 25% of the patients, and diabetes in 11%. No significant differences were noticed in the main baseline characteristics. Echocardiographic features of these patients were remarkable for a baseline ejection fraction of 28%, left ventricle end-systolic diameter of 58 mm and end-diastolic diameter of 70 mm. Target INR for warfarin treatment was 2-3. Primary outcome was the composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, peripheral or pulmonary embolism, hospitalisation, or HF worsening[22].

Quality of reporting assessment is available in Figure 2. The main methodological flaws were the open-label design of WASH and the unknown method of allocation concealment in HELAS.

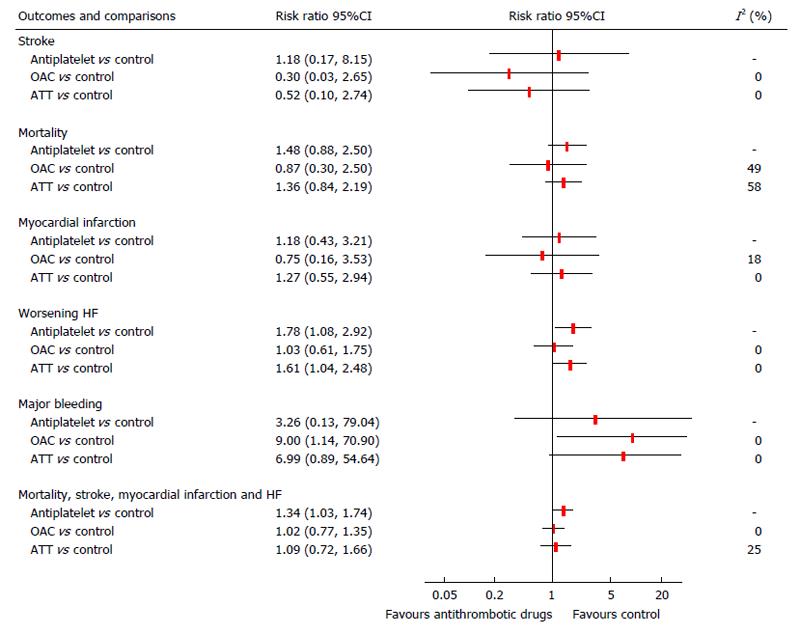

Meta-analysis was performed for the following comparisons: antiplatelet drugs vs control, anticoagulant drugs vs control, and antithrombotic drugs (antiplatelet plus anticoagulant drugs) vs control.

While anticoagulation vs control data was derived from both WASH and HELAS studies[21,22], WASH study was the only that provided data for antiplatelet (acetylsalicylic acid) vs placebo[21]. For quantitative evaluation of overall antithrombotic treatment in this population, we considered both oral anticoagulation and antiplatelet from WASH study as a single arm and efficacy was directly obtained from WASH study[21].

Antithrombotic drugs did not reduce stroke risk against placebo or no treatment, with RR = 1.18 (95%CI: 0.17-8.15) for antiplatelet drugs, RR = 0.30 (95%CI: 0.03-2.65) for anticoagulants, and RR = 0.52 (95%CI: 0.10-2.74) for overall antithrombotic drugs.

Antithrombotic drugs showed an increased risk of CHF worsening (RR = 1.61, 95%CI: 1.04-2.48), mainly due to the single antiplatelet drug studied, acetylsalicylic acid, which had RR = 1.78 (95%CI: 1.08-2.92), while oral anticoagulants were not different from controls (RR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.61-1.75).

Warfarin showed a significant increased risk of major bleeding (RR = 9.00, 95%CI: 1.14-70.90) and acetylsalicylic acid showed a non-significant trend (RR = 3.26, 95%CI: 0.13-79.04). The RR for overall major bleeding risk with antithrombotic drugs was 6.99 (95%CI: 0.89-54.64).

None of the antithrombotic drugs or overall antithrombotic treatment showed reduction of mortality and myocardial infarction risk in patients with systolic HF and sinus rhythm.

Antiplatelet drug/acetylsalicylic acid, but not warfarin, showed increased risk of the composite outcome of mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction, and worsening HF, most probably due to the increased risk of CHF worsening. Statistical heterogeneity was present in the evaluation of mortality when comparing antithrombotic drugs with control (I2 = 58%). Figure 3 shows the pooled results. Publication bias was not evaluated due to the scarcity of studies[28].

Our main findings were the lack of proven efficacy of antithrombotic treatments, in patients with systolic HF and sinus rhythm, in the risk reduction of clinically important outcomes such as stroke, mortality and myocardial infarction; moreover, warfarin is associated to a significant 9-fold increased risk of major bleeding; and acetylsalicylic acid was associated with increased risk of CHF worsening.

The spotlight of this theme looks for Warfarin vs Acetylsalicylic acid comparison. By conducting this systematic review, the authors aimed to move back to the original problem and ask the question of whether antithrombotic treatments are, in the first place, effective in the treatment of CHF with sinus rhythm. If we accept that RCTs are the unique type of clinical studies that can prove causality with a reasonable margin of error, our results show that these interventions still have to prove their efficacy in this population, knowing that they owe an important bleeding risk. Furthermore, our attempt to perform a bayesian mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis, with data from clopidogrel arm from WATCH study[20], and warfarin vs acetylsalicylic acid presented in multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses, failed due to high inconsistency in the statistical analysis of the network (data not shown). Although this inconsistence strongly compromises the results of such exercise, it is worth to report that placebo had a high probability of being the best treatment option. This reinforces the need of further trials to elucidate whether these interventions do/do not interfere with the prognosis, rather than have contradictory signs.

Accordingly, the 2012 consensus document of the HF Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis corroborates our conclusions[29]. This consensus document stated that warfarin and acetylsalicylic acid should not be routinely used for thromboprophylaxis in patients with systolic HF and sinus rhythm, in the absence of concomitant comorbidities with clear indications for anticoagulation (e.g., AF) or acetylsalicylic acid (e.g., documented coronary artery disease).

Safety concerns regarding acetylsalicylic acid and HF (in patients with previously optimized background therapy with drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) were previously mentioned[30-32]. However if we consider warfarin as a “negative control”, the pooled rates of HF worsening (after the WARCEF trial) were similar between acetylsalicylic acid and warfarin[7].

Along this century, antithrombotic treatment has gone forward in many therapeutic indications, but in patients with systolic HF and sinus rhythm the evidence to determine the prognostic importance of antithrombotic treatment (individually or globally) remained stationary and unsatisfactory for those who have to deal with CHF patients with sinus rhythm.

This systematic review with meta-analysis has limitations attributed to included studies and analysis method.

As for included studies, WASH study had an open-label design; the control arm of this study was a no-antithrombotic treatment group (i.e., not a placebo controlled trial), and included 7% of patients with AF that could not be excluded in the analyses. Furthermore the dosage of acetylsalicylic acid used in this trial was considerably higher than recommended[33].

Both studies had different proportions of HF etiologies. Although it can be important, particularly in ischemic HF cases where acetylsalicylic acid may play recognized prognostic role, here we aimed evaluate the thrombotic and embolic risk of patients with clinically important left ventricle impairment.

Major bleeding definitions were not common along the included trials. Worsening HF was defined by the investigator in WASH and no definition was provided in HELAS.

Periods of unrecognized paroxysmal AF could have biased of results. However it would bias favouring the antithrombotic drugs, which did not occur.

In conclusions, current evidence does not support the routine use of antithrombotic drugs (anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs) for thromboprophylaxis in patients with systolic HF and sinus rhythm, as it carries a well known and documented bleeding risk without proven benefits compared to placebo or no antithrombotic treatment.

Joaquim J Ferreira had speaker and consultant fees with GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, TEVA, Lundbeck, Solvay, Abbott, Bial, Merck-Serono, Grunenthal, and Merck Sharp and Dohme. Fausto J Pinto had consultant and speaker fees with Astra Zeneca, Bayer and Boehringer Ingelheim. The referred companies were not directly or indirectly in this work.

In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), chronic heart failure (CHF) increases thromboembolic risk and oral anticoagulation is essential to decrease the risk of thromboembolic complications. Evidence suggests a positive association between CHF, impaired hemostasis and thromboembolic events. Whether antithrombotic drugs have an prognosis impact in patients with CHF in sinus rhythm (i.e., without history of AF) is still very debated.

Anticoagulation has been established as the gold standard treatment of stroke and embolism prevention in AF. The WARCEF trial did not show differences between warfarin and acetylsalicylic acid concerning major cardiovascular events in patients with CHF and sinus rhythm. Warfarin reduced the risk of ischemic stroke in this trial. However the efficacy of any of these drugs compared should be evaluated before drawing any conclusions and recommendations.

Based on the best available evidence (2 randomized controlled trials Warfarin/Aspirin Study in Heart failure and Heart failure Long-term Antithrombotic Study), this systematic review emphasizes the lack of efficacy of any antithrombotic drugs (individually or pooled together) in patients with CHF and sinus rhythm. In addition should be considered that these drugs increase significantly the risk of major bleeding.

Warfarin and acetylsalicylic acid should not be routinely used for thromboprophylaxis in patients with systolic HF and sinus rhythm, in the absence of concomitant comorbidities with clear indications for anticoagulation (e.g., AF) or acetylsalicylic acid (e.g., documented coronary artery disease).

A systematic review and meta-analysis of two studies addressing antithrombotic drugs in patients with CHF and sinus rhythm. The manuscript is well written and adds new points to the discussion of anticoagulation.

P- Reviewer: Aronow WS, Rauch B, Skobel E S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart. 2007;93:1137-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1124] [Cited by in RCA: 1270] [Article Influence: 70.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xuan J, Duong PT, Russo PA, Lacey MJ, Wong B. The economic burden of congestive heart failure in a managed care population. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:693-700. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Braunschweig F, Cowie MR, Auricchio A. What are the costs of heart failure? Europace. 2011;13 Suppl 2:ii13-ii17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hays AG, Sacco RL, Rundek T, Sciacca RR, Jin Z, Liu R, Homma S, Di Tullio MR. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction and the risk of ischemic stroke in a multiethnic population. Stroke. 2006;37:1715-1719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Loh E, Sutton MS, Wun CC, Rouleau JL, Flaker GC, Gottlieb SS, Lamas GA, Moyé LA, Goldhaber SZ, Pfeffer MA. Ventricular dysfunction and the risk of stroke after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:251-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines-CPG; Document Reviewers. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation--developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2012;14:1385-1413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 881] [Cited by in RCA: 967] [Article Influence: 74.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Homma S, Thompson JL, Pullicino PM, Levin B, Freudenberger RS, Teerlink JR, Ammon SE, Graham S, Sacco RL, Mann DL. Warfarin and aspirin in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1859-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shah S, Parra D, Rosenstein R. Warfarin versus aspirin in heart failure and sinus rhythm. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:771; author reply 772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hopper I, Skiba M, Krum H. Updated meta-analysis on antithrombotic therapy in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:69-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kumar G, Goyal MK. Warfarin versus aspirin for prevention of stroke in heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:1279-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee M, Saver JL, Hong KS, Wu HC, Ovbiagele B. Risk-benefit profile of warfarin versus aspirin in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm: a meta-analysis. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:287-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rengo G, Pagano G, Squizzato A, Moja L, Femminella GD, de Lucia C, Komici K, Parisi V, Savarese G, Ferrara N. Oral anticoagulation therapy in heart failure patients in sinus rhythm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e52952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liew AY, Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, O’ Donnell M, Hart RG. Efficacy and safety of warfarin vs antiplatelet therapy in patients with systolic heart failure and sinus rhythm: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:199-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18665] [Cited by in RCA: 17544] [Article Influence: 1096.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration 2011; Available from: http:// www.cochrane-handbook.org. |

| 16. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46553] [Article Influence: 2116.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:820-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1858] [Cited by in RCA: 1996] [Article Influence: 71.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in RCA: 2643] [Article Influence: 110.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:676-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1326] [Cited by in RCA: 1560] [Article Influence: 82.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Massie BM, Collins JF, Ammon SE, Armstrong PW, Cleland JG, Ezekowitz M, Jafri SM, Krol WF, O’Connor CM, Schulman KA. Randomized trial of warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with chronic heart failure: the Warfarin and Antiplatelet Therapy in Chronic Heart Failure (WATCH) trial. Circulation. 2009;119:1616-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cleland JG, Findlay I, Jafri S, Sutton G, Falk R, Bulpitt C, Prentice C, Ford I, Trainer A, Poole-Wilson PA. The Warfarin/Aspirin Study in Heart failure (WASH): a randomized trial comparing antithrombotic strategies for patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2004;148:157-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cokkinos DV, Haralabopoulos GC, Kostis JB, Toutouzas PK; HELAS investigators. Efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in chronic heart failure: the HELAS study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:428-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lip GY, Gibbs CR. Antiplatelet agents versus control or anticoagulation for heart failure in sinus rhythm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;CD003333. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Sirajuddin RA, Miller AB, Geraci SA. Anticoagulation in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and sinus rhythm: a critical literature review. J Card Fail. 2002;8:48-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lip GY, Gibbs CR. Anticoagulation for heart failure in sinus rhythm: a Cochrane systematic review. QJM. 2002;95:451-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lip GY, Gibbs CR. Antiplatelet agents versus control or anticoagulation for heart failure in sinus rhythm: a Cochrane systematic review. QJM. 2002;95:461-468. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Lip GY, Wrigley BJ, Pisters R. Anticoagulation versus placebo for heart failure in sinus rhythm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD003336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D (editors). Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention. Version 5.1.0. [Updated 2011; March]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 Available from: http//www.cochrane-handbook.org. |

| 29. | Lip GY, Ponikowski P, Andreotti F, Anker SD, Filippatos G, Homma S, Morais J, Pullicino P, Rasmussen LH, Marin F. Thrombo-embolism and antithrombotic therapy for heart failure in sinus rhythm. A joint consensus document from the ESC Heart Failure Association and the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:681-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cleland JG, Bulpitt CJ, Falk RH, Findlay IN, Oakley CM, Murray G, Poole-Wilson PA, Prentice CR, Sutton GC. Is aspirin safe for patients with heart failure? Br Heart J. 1995;74:215-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ahmed A. Interaction between aspirin and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: should they be used together in older adults with heart failure? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1293-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Teo KK, Yusuf S, Pfeffer M, Torp-Pedersen C, Kober L, Hall A, Pogue J, Latini R, Collins R; ACE Inhibitors Collaborative Group. Effects of long-term treatment with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors in the presence or absence of aspirin: a systematic review. Lancet. 2002;360:1037-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Campbell CL, Smyth S, Montalescot G, Steinhubl SR. Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297:2018-2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |