Published online May 26, 2014. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v2.i2.42

Revised: January 18, 2014

Accepted: March 3, 2014

Published online: May 26, 2014

Processing time: 208 Days and 22.5 Hours

AIM: To reviewed the literature and evaluated the scope and timing of the application of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)/endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) and cholecystectomy.

METHODS: A pooled odds ratio (OR) and a pooled mean difference with the 95%CI were used to assess the enumeration data of included studies. A pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) and a pooled mean difference with the 95%CI were used to assess the measurement data of included studies. Statistical heterogeneity was tested with the χ2 test. According to forest plots, heterogeneity was not significant, so the fixed effect model was adopted. The significance of the pooled OR was determined by the Z test and statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

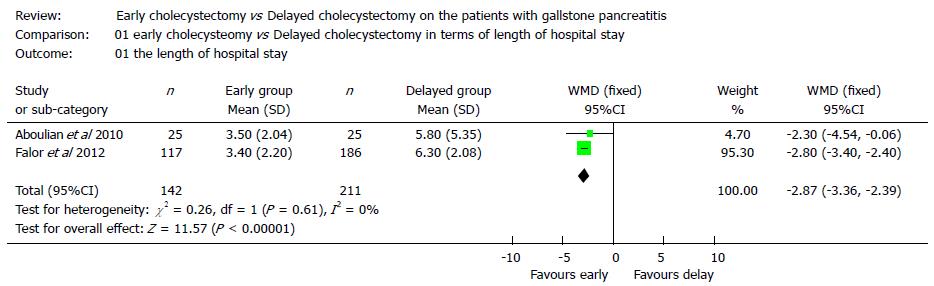

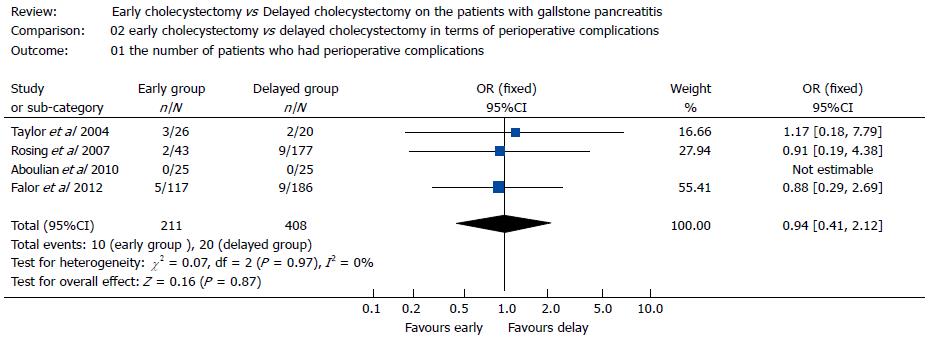

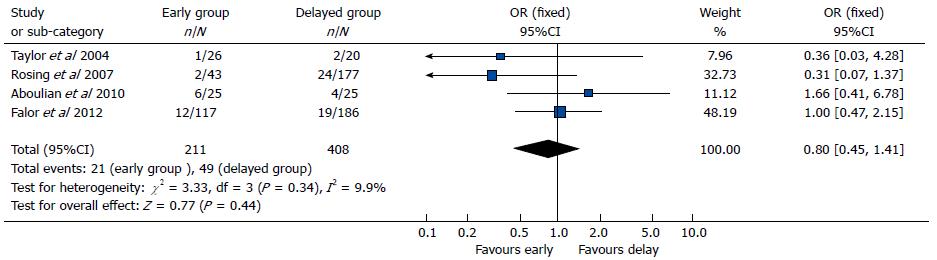

RESULTS: Data were collected from two studies (353 patients, 142 in the early cholecystectomy group and 211 in the delayed cholecystectomy group) regarding the length of hospital stay [The WMD was -2.87 (95%CI: -3.36--2.39, P < 0.01). Data were collected from four studies (618 patients, 211 in the early cholecystectomy group and 408 in the delayed cholecystectomy group) regarding perioperative complications (OR = 0.94, 95%CI: 0.41-2.12, P > 0.05). Data were collected from four studies (618 patients, 211 in the early cholecystectomy group and 408 in the delayed cholecystectomy group) on the number of patients who underwent ERCP± ES postoperatively (OR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.45-1.41, P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Cholecystectomy offers better protection than ES against further bouts of pancreatitis in patients with gallstone pancreatitis, although ES is an acceptable alternative.

Core tip: In this study we reviewed the literature and evaluated the scope and timing of the application of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)/endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) and cholecystectomy. We also carried out a meta-analysis regarding the timing of cholecystectomy and found that early cholecystectomy administered to patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis could reduce the length of hospital stay with no increase in perioperative complications or the incidence of postoperative ERCP ± ES.

- Citation: Hu C, Shen SQ, Chen ZB. Treatment strategy for gallstone pancreatitis and the timing of cholecystectomy. World J Meta-Anal 2014; 2(2): 42-48

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v2/i2/42.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v2.i2.42

Acute pancreatitis is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality[1]. In fact, approximately 20% of patients with acute pancreatitis will present a severe disease course, with a 10%-30% mortality rate[2]. The most common causes of acute pancreatitis include gallstones and alcohol abuse which together account for more than 80% of cases, and gallstones alone cause 30%-75% of cases[3,4]. Apart from these two main causes, hyperlipidemia, medication use, hypercalcemia, trauma, familial pancreatitis, and other rare origins also can lead to pancreatitis[5].

The theories of pathogenesis of gallstone pancreatitis (GSP) are still controversial now. The common channel theory proposes that a stone lodged at the ampulla of Vater creates a common channel between the bile and pancreatic ducts, which allows bile reflux into the pancreatic duct (PD) and subsequent activation of pancreatic enzymes[6]. In contrast, the duodenal reflux theory postulates that the passage of biliary stones creates incompetence of the sphincter of Oddi, which results in the reflux of duodenal contents into the PD and subsequently leads to the activation of pancreatic proenzymes and the development of pancreatitis[7]. The third prominent theory is the obstruction theory, which holds that a gallstone or inflammation with edema consequent to gallstone passage may impact or transiently obstruct the common bile duct (CBD) and PD at the level of the ampulla of Vater, which leads to extravasation of digestive enzymes into the gland parenchyma[8]. Recently, many studies have reported that inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, interleukins (IL-6 and IL-8), platelet activating factor, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), also play an important role in the systemic complications of acute pancreatitis[9,10].

Most of the patients with gallstone pancreatitis demonstrate mild to moderate clinical disease, and some can recover with conservative management. The conservative management of gallstone pancreatitis includes bowel rest, fluid resuscitation, total parenteral nutrition or enteral nutrition, and parenteral analgesia, which is similar to the management approach for any form of pancreatitis. However, in contrast to other forms of pancreatitis, for instance, gallstone pancreatitis often requires surgery. According to the pathogenesis of gallstone pancreatitis, we know that removing the gallstones and resolving the obstruction of CBD and PD is the key point for management, although the optimal method for removing the gallstones and resolving the obstruction remains controversial. In particular, the application and timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)/endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) or cholecystectomy remain the subject of current debate.

To assess the method and timing of surgical treatment for gallstone pancreatitis, we searched the relevant literature from the Cochrane Library and the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases up to september 20th, 2013. The search strategy included the following MESH terms: “gallstone pancreatitis” and “endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography” and “cholecystectomy”.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study population: patients with mild gallstone acute pancreatitis (less than 3 Ranson criteria); (2) intervention: ERCP with or without ES vs cholecystectomy; (3) outcome measures: the length of hospital stay, the incidence of perioperative complication and the mortality; and (4) study design: randomized controlled trial. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with severe gallstone pancreatitis (3 or more Ranson criteria); (2) pancreatitis from other causes; (3) suspected concomitant acute cholangitis; and (4) articles reporting non-comparative studies.

For statistical analysis, Review Manager (RevMan) software Version 4.2 was used (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). A pooled odds ratio (OR) and a pooled mean difference with the 95%CI were used to assess the enumeration data of included studies. A pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) and a pooled mean difference with the 95%CI were used to assess the measurement data of included studies. Statistical heterogeneity was tested with the χ2 test. According to forest plots, heterogeneity was not significant, so the fixed effect model was adopted. The significance of the pooled OR was determined by the Z test and statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

We found no randomized controlled trial or retrospective study concerning the application of ERCP with or without ES vs cholecystectomy. Therefore, we reviewed the previously published literature for studies evaluating ERCP/ES and cholecystectomy and then assessed the scope of the application of ERCP/ES and cholecystectomy.

Four studies showing that early cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis may decrease hospital stay without increasing morbidity or mortality were identified; among these studies, 1 was a randomized controlled trial study and 3 were retrospective studies. All of these studies were single-center studies, and their main characteristics are listed in Table 1. Based on these 4 studies, we carried out a meta-analysis regarding the timing of cholecystectomy in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis.

| Ref. | Group | POT | No. of patients | LOS | ERCP ± ES postoperative | Compli-cations |

| Aboulian et al[44], 2010 | Early | 35.1 | 25 | 3.5 ± 2.04 | 6 | 0 |

| Delayed | 77.8 | 25 | 5.8 ± 5.35 | 4 | 0 | |

| Rosing et al[42], 2007 | Early | 48 | 43 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Delayed | 120 | 177 | 7 | 24 | 9 | |

| Taylor et al[43], 2004 | Early | 43.2 | 26 | 3.5 | 6 (1) | 3 |

| Delayed | 55.2 | 20 | 4.7 | 7 (2) | 2 | |

| Falor et al[45], 2012 | Early | < 48 | 117 | 3.4 ± 2.20 | 19 (12) | 5 |

| Delayed | > 48 | 186 | 6.3 ± 2.08 | 51 (19) | 9 |

Length of hospital stay: Data were collected from two studies (353 patients, 142 in the early cholecystectomy group and 211 in the delayed cholecystectomy group) regarding the length of hospital stay (LOS). The overall meta-analysis (Figure 1) indicated that early cholecystectomy for the patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis could significantly decrease the LOS compared with delayed cholecystectomy; the WMD was -2.87, (95%CI: -3.36--2.39, P < 0.01).

Perioperative complications: Data were collected from four studies (618 patients, 211 in the early cholecystectomy group and 408 in the delayed cholecystectomy group) regarding perioperative complications. The overall meta-analysis (Figure 2) showed that the effect of early cholecystectomy on perioperative complications in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis was inconclusive (OR = 0.94, 95%CI: 0.41-2.12, P > 0.05).

Postoperative ERCP ± ES: Data were collected from four studies (618 patients, 211 in the early cholecystectomy group and 408 in the delayed cholecystectomy group) on the number of patients who underwent ERCP± ES postoperatively. The overall meta-analysis (Figure 3) indicated that the effect of early cholecystectomy on the number of patients who underwent ERCP ± ES postoperatively was also inconclusive (OR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.45-1.41, P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

ERCP/ES is one of the most technically challenging endoscopic procedures performed by gastroenterologists and surgeons with special training. This approach is well suited for the evaluation of diseases of the bile ducts and pancreas. However, it has been reported that the rate of complications due to ERCP ranges from 5% to 7%, with pancreatitis and bleeding as the most common complications[11-14]. Moreover, death directly related to the procedure occurs in approximately 0.4% of cases in large prospective studies[13,14]. Therefore, many surgeons do not advocate for use ERCP/ES as the preferred treatment strategy for gallstone pancreatitis. A meta-analysis conducted by Uy et al[15] showed a trend that the mortality of patients receiving early ERCP with or without sphincterotomy in the setting of acute gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis was higher than that of patients who received conservative management (RR = 1.92, 95%CI: 0.86-4.32 P = 0.11). A study conducted by Sees et al[16] also suggested that in patients with mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis, preoperative ERCP/ES led to a higher rate of postoperative pancreatitis and an increased length of hospitalization, especially in patients with choledocholithiasis. In addition, numerous other studies have also shown that in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis who received early ERCP/ES presented more severe complications and did not benefit from the procedure[17-19].

Although ERCP/ES has limitations related due to potential morbidity and mortality, ERCP/ES also has its incomparable advantage. For example, a recent large-sample retrospective cohort study conducted by Hwang et al[20] analyzed the risk of developing recurrent gallstone pancreatitis in patients who never received a cholecystectomy. In this study, a total of 1119 patients were identified, including 802 who received no intervention and 317 who received ERCP. After a median follow-up of 2.3 years, the risk of recurrent pancreatitis was 8.2% and 17.1% in patients who received ERCP and those who received no intervention, respectively (P < 0.001). The median time to recurrence was also longer in the ERCP group(11.3 vs 10.1 mo), and the recurrence rates at 1, 2 and 5 years in the ERCP group were all lower than those in the non-intervention group (5.2%, 7.4%, 11.1% vs 11.3%, 16.1%, 22.7%). These results suggested that ERCP could mitigate the risk of recurrent pancreatitis and should be considered during initial hospitalization if cholecystectomy was not performed. Kaw et al[21] also found that the recurrence of pancreatitis after ERCP with ES alone for the treatment of gallstone pancreatitis was rare and the complication rate, as well as the rate of serious complications, was higher in comparison to cholecystectomy but not significant. Also recently, the most acceptable range for the use of ERCP was shown to be in high-risk surgical patients and the elderly[22-25], as cholecystectomy may lead to a higher rate of morbidity and mortality in these patients. Another condition for which ERCP/ES is recommended is severe gallstone pancreatitis, and it is reported that up to 25% of patients with gallstone pancreatitis experienced severe pancreatitis[6]. In addition to intensive care monitoring for the management of associated systemic complications, most of these patients are initially managed with ERCP and ES if common bile duct stones are found. Moreover, surgery is delayed for approximately 3 wk because numerous studies have shown that early cholecystectomy is associated with increased morbidity and mortality[10,26-28]. There are also other conditions that may benefit from ERCP/ES, such as cholangitis or obstructive jaundice associated with gallstone pancreatitis[29,30].

The United Kingdom guidelines for the management of gallstone pancreatitis published by the British Society of Gastroenterology in 1998[31] and 2005[32] suggest that all patients with mild GSP should be offered definitive treatment, i.e., cholecystectomy, if they are fit for surgery. Several studies have also reported that cholecystectomy can reduce the risk of recurrence or further attack for patients with GSP[33-36]. Moreover, cholecystectomy is a lower-risk procedure, and the biliary complications attributable to gallstones in the gallbladder, such as cholecystitis, are avoided[37]. Therefore, for the treatment of GSP, it is generally agreed that all patients with acute GSP who are sufficiently fit should undergo cholecystectomy.

Recent reports have also presented controversial findings regarding the timing of surgery. According to several experts cholecystectomy for GSP can be delayed from the inciting pancreatitis. In their opinion, postponing cholecystectomy 6-8 wk may reduce the acute inflammation and decrease the technical difficulty of cholecystectomy and possibly lower the conversion rate[38]. However, in the last decade, the standard timing for cholecystectomy has supported earlier intervention. For example, a large-sample (8631 patients) observational study in 2009 divided study patients into four groups according to the treatment policy: cholecystectomy during index stay (group 1); cholecystectomy within 30 d of index admission (group 2); sphincterotomy, but not cholecystectomy within 30 d of index admission (group 3); and neither cholecystectomy nor sphincterotomy within 30 d of index admission (group 4). The results showed that group 1 required a slightly longer length of stay in the hospital compared to group 2, although these patients had had much fewer readmissions for biliary complications. Similar to the study mentioned above, several observational studies have supported the use of doing cholecystectomy within 2 wk of index admission to prevent gallstone pancreatitis recurrence[39,40].

Some studies have even suggested that 2 wk after index admission is too long to wait, as patients presented with unacceptably high rates for recurrence of gallstone pancreatitis. For example, Ito et al[41], found that even following the guidelines that performing cholecystectomy within 2 wk of index admission (according to the guidelines), there remained a 33% rate of biliary related complications including a 13% recurrence rate for pancreatitis rate. As a result, so some experts have suggested that cholecystectomy should be performed within 48 h of admission for mild gallstone pancreatitis before serum pancreatic enzymes are normal and before abdominal pain has completely resolved. Indeed, some retrospective studies have confirmed that early cholecystectomy can shorten the length of hospital stay with no increase in complications or mortality or technical difficulty[42-45].

The timing of cholecystectomy in patients with severe pancreatitis is different from that in patients with mild disease, as the former patients often have contraindications to surgery due to various physiologic derangements or the inflammatory response associated with severe pancreatitis. Thus, the treatment strategy for these patients is early ERCP/ES and cholecystectomy is delayed until the signs of lung injury and systemic disturbance have resolved, generally between 3 and 4 wk.Various studies have shown less controversy over the timing of cholecystectomy for these patients.

Our present meta-analysis also obtained the conclusion that early cholecystectomy in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis could reduce the length of hospital stay with no increase in perioperative complications or the incidence of postoperative ERCP ± ES. However, there were some limitations to our meta-analysis. First, only four studies were included in our study, of which only one study was a randomized controlled trial and the other three were retrospective studies. Second, individual patient data were not used. Third, the publication bias may have been present because the quantity of the studies included was so small. Therefore, to confirm that early cholecystectomy is indeed both superior to delayed cholecystectomy and safe, a multicenter randomized controlled trial is needed.

In conclusion, cholecystectomy offers better protection than ES against further bouts of pancreatitis in patients with GSP, although ES is an acceptable alternative. Patients with mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis should receive cholecystectomy during index admission, although patients with more severe disease will require early ERCP/ES and cholecystectomy should therefore be delayed, depending on the clinical circumstances. For patients at a patients have high risk for surgery or the elderly, ERCP and ES should represent first-choice treatments.

Acute pancreatitis is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. Approximately 30%-75% of cases are caused by gallstones and the management of gallstone pancreatitis remains challenging.

The role and timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)/endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) and cholecystectomy in the management of gallstone pancreatitis have been a subject of much debate in recent years.

In this study the authors reviewed the literature and evaluated the scope and timing of the application of ERCP/ES and cholecystectomy. The authors also carried out a meta-analysis regarding the timing of cholecystectomy and found that early cholecystectomy administered to patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis could reduce the length of hospital stay with no increase in perioperative complications or the incidence of postpoerative ERCP ± ES.

For patients at a patients have high risk for surgery or the elderly, ERCP and ES should represent first-choice treatments.

Hu et al evaluated the management of gallstone pancreatitis. They demonstrated that cholecystectomy offers better protection than ES against further bouts of pancreatitis in patients with gallstone pancreatitis, but ES is an acceptable alternative. Patients with mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis should have cholecystectomy during index admission, but patients with more severe disease will require early ERCP/ES and cholecystectomy should be delayed, depending on the clinical circumstances. If patients have high risk of surgery or the elderly, ERCP and ES is the first choice.

P- Reviewers: Biondi-Zoccai G, Cui WP, Messori A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Mitchell RM, Byrne MF, Baillie J. Pancreatitis. Lancet. 2003;361:1447-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Whitcomb DC. Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2142-2150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Steer ML. Classification and pathogenesis of pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am. 1989;69:467-480. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Agrawal S, Jonnalagadda S. Gallstones, from gallbladder to gut. Management options for diverse complications. Postgrad Med. 2000;108:143-146, 149-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sakorafas GH, Tsiotou AG. Etiology and pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis: current concepts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:343-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Frakes JT. Biliary pancreatitis: a review. Emphasizing appropriate endoscopic intervention. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:97-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McCutcheon AD. Gallstone pancreatitis. Lancet. 1988;2:166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Senninger N, Moody FG, Coelho JC, Van Buren DH. The role of biliary obstruction in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis in the opossum. Surgery. 1986;99:688-693. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kusske AM, Rongione AJ, Reber HA. Cytokines and acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:639-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mergener K, Baillie J. Endoscopic treatment for acute biliary pancreatitis. When and in whom? Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1999;28:601-613, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mallery JS, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, Goldstein JL, Hirota WK, Jacobson BC, Leighton JA, Raddawi HM, Varg JJ, Waring JP. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:633-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2036] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, De Bernardin M, Ederle A, Fina P, Fratton A. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Uy MC, Daez ML, Sy PP, Banez VP, Espinosa WZ, Talingdan-Te MC. Early ERCP in acute gallstone pancreatitis without cholangitis: a meta-analysis. JOP. 2009;10:299-305. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Sees DW, Martin RR. Comparison of preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and laparoscopic cholecystectomy with operative management of gallstone pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;174:719-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fölsch UR, Nitsche R, Lüdtke R, Hilgers RA, Creutzfeldt W. Early ERCP and papillotomy compared with conservative treatment for acute biliary pancreatitis. The German Study Group on Acute Biliary Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chang L, Lo S, Stabile BE, Lewis RJ, Toosie K, de Virgilio C. Preoperative versus postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2000;231:82-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Himal HS. Preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is not necessary in mild gallstone pancreatitis. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:782-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hwang SS, Li BH, Haigh PI. Gallstone pancreatitis without cholecystectomy. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:867-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kaw M, Al-Antably Y, Kaw P. Management of gallstone pancreatitis: cholecystectomy or ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:61-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pezzilli R. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in acute biliary pancreatitis: A question of anesthesiological risk. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;1:17-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Trust MD, Sheffield KM, Boyd CA, Benarroch-Gampel J, Zhang D, Townsend CM, Riall TS. Gallstone pancreatitis in older patients: Are we operating enough? Surgery. 2011;150:515-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Welbourn CR, Beckly DE, Eyre-Brook IA. Endoscopic sphincterotomy without cholecystectomy for gall stone pancreatitis. Gut. 1995;37:119-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bignell M, Dearing M, Hindmarsh A, Rhodes M. ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES): a safe and definitive management of gallstone pancreatitis with the gallbladder left in situ. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2205-2210. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Tang E, Stain SC, Tang G, Froes E, Berne TV. Timing of laparoscopic surgery in gallstone pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1995;130:496-499; discussion 496-500. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL, London NJ, Bailey IA, James D, Fossard DP. Controlled trial of urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic sphincterotomy versus conservative treatment for acute pancreatitis due to gallstones. Lancet. 1988;2:979-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in RCA: 470] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fan ST, Lai EC, Mok FP, Lo CM, Zheng SS, Wong J. Early treatment of acute biliary pancreatitis by endoscopic papillotomy. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:228-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 542] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Byrne MF. Gallstone pancreatitis--who really needs an ERCP? Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:15-17. [PubMed] |

| 30. | West DM, Adrales GL, Schwartz RW. Current diagnosis and management of gallstone pancreatitis. Curr Surg. 2002;59:296-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | United Kingdom guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 1998;42 Suppl 2:S1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 3:iii1-iii9. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Moreau JA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, DiMagno EP. Gallstone pancreatitis and the effect of cholecystectomy: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:466-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Judkins SE, Moore EE, Witt JE, Barnett CC, Biffl WL, Burlew CC, Johnson JL. Surgeons provide definitive care to patients with gallstone pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2011;202:673-677; discussion 677-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Frei GJ, Frei VT, Thirlby RC, McClelland RN. Biliary pancreatitis: clinical presentation and surgical management. Am J Surg. 1986;151:170-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | El-Dhuwaib Y, Deakin M, David GG, Durkin D, Corless DJ, Slavin JP. Definitive management of gallstone pancreatitis in England. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94:402-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sandzén B, Haapamäki MM, Nilsson E, Stenlund HC, Oman M. Cholecystectomy and sphincterotomy in patients with mild acute biliary pancreatitis in Sweden 1988 - 2003: a nationwide register study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Tate JJ, Lau WY, Li AK. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1994;81:720-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | McCullough LK, Sutherland FR, Preshaw R, Kim S. Gallstone pancreatitis: does discharge and readmission for cholecystectomy affect outcome? HPB (Oxford). 2003;5:96-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Monkhouse SJ, Court EL, Dash I, Coombs NJ. Two-week target for laparoscopic cholecystectomy following gallstone pancreatitis is achievable and cost neutral. Br J Surg. 2009;96:751-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ito K, Ito H, Whang EE. Timing of cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis: do the data support current guidelines? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:2164-2170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Rosing DK, de Virgilio C, Yaghoubian A, Putnam BA, El Masry M, Kaji A, Stabile BE. Early cholecystectomy for mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis shortens hospital stay. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:762-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Taylor E, Wong C. The optimal timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in mild gallstone pancreatitis. Am Surg. 2004;70:971-975. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Aboulian A, Chan T, Yaghoubian A, Kaji AH, Putnam B, Neville A, Stabile BE, de Virgilio C. Early cholecystectomy safely decreases hospital stay in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:615-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Falor AE, de Virgilio C, Stabile BE, Kaji AH, Caton A, Kokubun BA, Schmit PJ, Thompson JE, Saltzman DJ. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis: time for a paradigm shift. Arch Surg. 2012;147:1031-1035. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |