INTRODUCTION

Frailty refers to the difficulty in maintaining homeostatic balance when responding to stressors, resulting from a decline in physiological reserves that often accompanies aging. Aging is associated with biological changes at the cellular level in most tissues and organs, an increase in chronic diseases, and a consequent decline in physiological and functional reserve, predisposing individuals to frailty[1]. This reduced capacity increases the risk of adverse health outcomes, such as falls, hospitalization, disability, placement in care facilities, and mortality, when faced with both external and internal challenges[2]. Contrary to common belief, not all elderly individuals are frail; only 3% to 7% of those aged 65 to 75 are considered frail, and this percentage increases to 32% in individuals over 90 years of age. Advanced age, a history of cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cerebrovascular disease are established risk factors for frailty[3]. While comorbidity, frailty, and disability often coexist among older adults, these conditions represent distinct concepts. Disability refers to difficulties in performing daily living activities or mobility, which do not necessarily impact organ systems. Frailty and disability are closely related; however, it is imperative to acknowledge that they are fundamentally different conditions. Recognizing this distinction is essential for effective intervention and support[4].

FRAILTY MODELS AND SCREENING

Frailty models can be classified into three main categories: The physical frailty phenotype, the deficit accumulation model (also known as the frailty index), and mixed physical and psychosocial models. In the physical frailty model, frailty is defined by the presence of three or more of the following criteria: Exhaustion, reduced muscle strength, weight loss, low walking speed, and low physical activity[2]. The deficit accumulation model focuses on the documentation of multimorbidity and counts the total number of deficits across various areas, such as physical function and cognition[5]. This model includes various assessments that evaluate different conditions, such as clinical findings, symptoms, chronic diseases, disabilities, and abnormal laboratory tests. The number of variables assessed can vary. A higher number of deficits suggests a greater degree of frailty. Since this model relies on a computer-based database program for evaluation, it requires an application-based assessment. This approach depends on either self-reported or clinically recorded deficits, which may introduce the potential for measurement bias[6]. The Canadian research team later developed the Clinical Frailty Scale, which is more practical for daily use and has demonstrated validity. In this scale, one of nine categories is selected based on a thorough geriatric assessment of the patient's clinical status[7]. Additionally, there are other screening tools that integrate psychosocial aspects of patients with physical parameters. The Edmonton FRAIL scale, Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI), and Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI) are tools used to assess frailty in the older adults, addressing physical, cognitive, and social aspects[8]. Research indicates that cognitive functions are often affected in frail individuals. The relationship between physical frailty and cognitive dysfunction is emphasized in many studies. A large-scale study involving 22952 patients showed that the prevalence of dementia in frail patients was 40%, whereas in non-frail patients, this rate was 11%[9]. Therefore, cognitive assessment should be performed on all frail patients. In 2013, criteria for diagnosing cognitive frailty were established, identifying it as the coexistence of physical frailty and mild cognitive impairment in patients who do not have a dementia diagnosis[10]. It is believed that similar pathophysiological factors exist between cognitive dysfunction and frailty. The most important factors include oxidative damage, vascular pathologies, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, nutritional habits, and genetic factors[11].

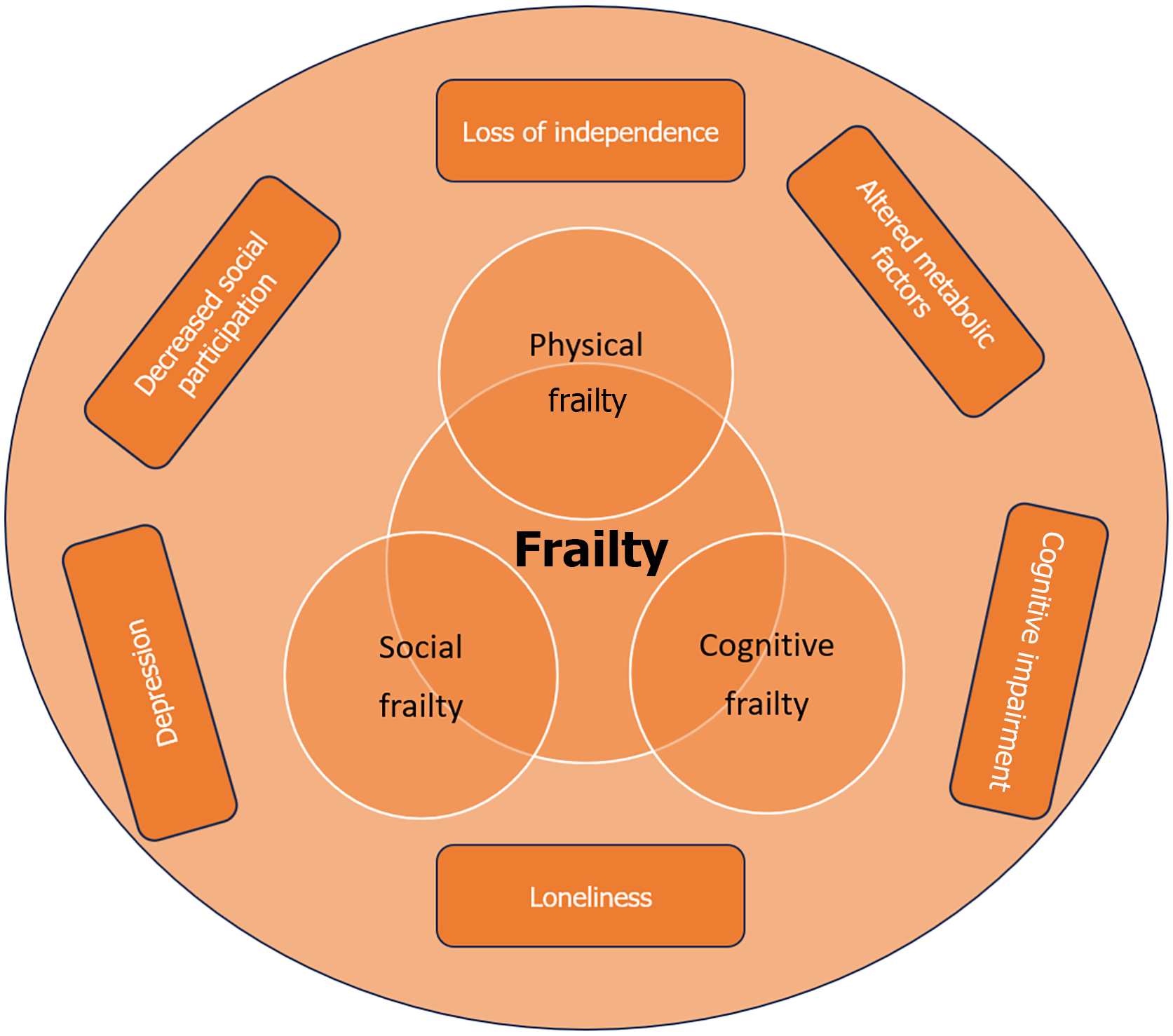

Frailty makes it challenging for individuals to perform daily activities and increases their need for social support. Physical frailty is the most commonly studied subtype of frailty, and numerous studies have demonstrated its predictive value for disability, hospitalization, and mortality[2,12,13]. In recent years, social frailty has emerged as a growing area of interest in the field of geriatric research. Research has shown that a lack of psychosocial support, often found alongside physical frailty, is more closely associated with negative health outcomes[14]. Social frailty is defined as the gradual loss of ability or resources needed to engage in social activities that fulfill basic social needs[15]. Social frailty in the older population should be considered a significant public health issue due to common social challenges faced by older individuals, such as family relationships, social exclusion and isolation, and financial difficulties[14]. The shift from an active lifestyle to a more sedentary one, along with a decrease in social activities, can lead older adults to feel increasingly isolated from their communities. The recent coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic exacerbated this isolation, particularly affecting seniors and increasing social frailty. Importantly, the social support received by older individuals is closely linked to both physical and cognitive frailty. There is a bidirectional relationship between social and physical frailty. Studies have shown that limited social interaction or a reduction in social connections can lead to a decline in physical activity and physical function[16-18]. Social frailty worsens physical frailty by limiting access to resources, reducing mobility, and leading to worse nutritional status and functional decline. Physical frailty reinforces social frailty by restricting independence, increasing isolation, and diminishing involvement in social activities[19]. A lack of social fulfillment and exhaustion may be linked to depression and slower gait speed, which can lead to further reduced social engagement. Conversely, difficulties in self-management are associated with cognitive function and can result in physical weakness, often leading to more limited physical and social activity[15]. A study has shown that low gait speed and low muscle strength, which are criteria of physical frailty, are independent risk factors for social decline[20]. In this regard, interventions focused on maintaining walking capacity and muscle strength could play a crucial role in the prevention of social frailty. Therefore, physical and social frailty should be evaluated holistically. The relationship between social, physical and cognitive frailty illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The relationship between physical, social and cognitive frailty.

CLINICAL IMPLEMENTATION

Frailty screening is recommended to all persons older than 70 years[3]. Frailty assessment tools differ in their focus, methodology, and clinical applicability. The Edmonton FRAIL scale and TFI are multidimensional tools that evaluate physical, psychological, and social domains, making them valuable in community and outpatient settings, although they rely on subjective reporting[21]. In contrast, the Physical Frailty Phenotype (Fried Criteria) focuses solely on physical markers, such as grip strength and gait speed, and is considered the gold standard for frailty research; however, it overlooks psychosocial factors. The Clinical Frailty Scale, a rapid clinician-rated tool, categorizes frailty based on functional dependence and comorbidities, making it practical for hospitals and emergency triage[22]. A study evaluating six frailty screening tools among nearly 1200 community-dwelling older adults compared these tools with a comprehensive geriatric assessment. The screening tools included the physical frailty index, FRAIL scale, Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, and three multidimensional tools: The TFI, GFI, and Comprehensive Frailty Assessment Instrument. All six tools demonstrated high specificity, with rates ranging from 81.1% to 98.7%. Among these, the three multidimensional tools (TFI, GFI, and Comprehensive Frailty Assessment Instrument) showed higher sensitivity[23]. Although there are various screening suggestions for frailty, it is recommended to assess gait speed using the 4-meter walking test due to its high sensitivity in the primary care settings. A walking speed of < 0.8 m/second and for the timed get-up-and-go test of 10 seconds are indicative of frailty[24]. Additionally, a score of 3 or higher on the PRISMA-7 questionnaire, which assesses the patient’s social, physical, and demographic characteristics, is considered an indicator of frailty[25]. The referral of patients for further evaluation is essential, as the frailty status can be modified or even reversed because it is dynamic process. A comprehensive geriatric assessment is the preferred holistic approach to define patients’ frailty status, enabling us to manage frailty through a personalized patient-centered plan that includes the prevention of polypharmacy, nutritional support, and a physical exercise program focused on flexibility, balance, strength, and endurance.

With the advancement of technology in recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) based applications may be useful for frailty screening in different settings[26]. AI-based applications may be beneficial for screening large populations and for the development of decision-making algorithms. In patients without cognitive impairment, self-administered scales can be utilized. Moreover, AI-driven programs may be developed to provide exercise recommendations, medication reminders, and notifications to local authorities for nutritional support in cases where patients require social assistance. As an example, virtual reality has become widely used in post-stroke cognitive rehabilitation, as well as in training for balance and gait abilities[27,28]. One benefit is that advancements in information technology may alleviate social isolation, which results from reduced human interaction and promote closer connections through remote communication[28].

Frailty prevention necessitates an interdisciplinary approach, and evidence suggests that multi-component interventions delivered by a multidisciplinary team, including geriatricians, physiotherapists, nurses, and nutritionists, effectively reduce frailty and contribute to the preservation of physical function[29,30].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, frailty is a significant geriatric syndrome encompassing physical, cognitive, and social dimensions, and it can be screened by assessing gait speed in older patients. Despite the numerous frailty guidelines published to date, there remains no consensus on its definition, screening, and diagnosis. AI-based frailty prediction models and AI-based approaches show promise in identifying frail patients and managing their care.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: European Geriatric Medicine Society.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Türkiye

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade C

Novelty: Grade A, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Oprea VD; Zhou XC S-Editor: Bai Y L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG