Published online Mar 18, 2025. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v13.i1.101226

Revised: January 30, 2025

Accepted: February 27, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2025

Processing time: 186 Days and 19.1 Hours

Chronic pouchitis remains a significant and prevalent complication following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis.

To identify potential risk factors for the development of chronic pouchitis.

Predictors of chronic pouchitis were investigated through a systematic review and meta-analysis. A comprehensive search of the Medline, EMBASE, and PubMed databases was undertaken to identify relevant studies published up to October 2023. Meta-analytic procedures employed random-effects models for the combi

Eleven studies with a total of 3722 patients, comprising 513 with chronic pouchitis and 3209 patients without, were included in the final analysis. Extraintestinal manifestation [odds ratio (OR) = 2.11, 95% confidence intervals (CI): 1.53-2.91, P < 0.001, I2 = 0%], specifically primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) (OR = 3.69, 95%CI: 1.40-9.21, P = 0.01, I2 = 48%), and extensive colitis (OR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.23-3.11, P = 0.00, I2 = 31%) were associated with an increased risk of chronic pouchitis. Other factors, including gender, smoking status, family history of inflammatory bowel disease and ileal pouch anal anastomosis surgical indication were not significantly associated with chronic pouchitis.

Extraintestinal manifestations, PSC and extensive colitis are associated with the development of chronic pouchitis. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive pre-operative assessment and tailored post operative management strategies.

Core Tip: Pouchitis is the most frequent complication after ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) surgery. This condition can significantly impact a person's quality of life, leading to social isolation. Identifying the risk factors of chronic pouchitis could lead to more personalized patient care, better preoperative counselling, and potential interventions to reduce the risk of chronic pouchitis in patients undergoing IPAA surgery for ulcerative colitis in the future and improve long-term outcomes.

- Citation: Khoo E, Gilmore R, Griffin A, Holtmann G, Begun J. Risk factors associated with the development of chronic pouchitis following ileal-pouch anal anastomosis surgery for ulcerative colitis. World J Meta-Anal 2025; 13(1): 101226

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v13/i1/101226.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v13.i1.101226

Ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) surgery is frequently performed in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) who have medically refractory disease, acute severe colitis, or histologically confirmed dysplasia. These conditions represent serious complications of UC that often require surgical intervention. While IPAA provides a valuable option for many patients, the fact that the 10-year colectomy rate of patients with UC has been reported as approximately 10%-30% in Western countries underscores several important points[1]. It highlights the potential for disease progression despite available treatments, the need for ongoing research into more effective therapies, and the importance of close monitoring and follow-up for UC patients. The preferred procedure for these conditions is a total proctocolectomy followed by surgical IPAA creation, but this statistic emphasizes that even with this procedure, some patients may still experience challenges post resection.

The most commonly reported complication following IPAA surgery is pouchitis, which can develop in up to 70% of patients within 5 years of surgery[2]. Pouchitis is diagnosed by active symptoms of pouch dysfunction and endoscopic evidence of inflammatory activity[3]. Antibiotics effectively control inflammation and symptoms for most pouchitis patients in the short term[4]. However, up to 30% of these patients develop chronic pouchitis, which may be responsive or resistant to antibiotics[5-7]. These conditions are termed “chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis” and “chronic anti

Treatment of chronic antibiotic-refractory and antibiotic-dependent pouchitis remains challenging due to a lack of evidence guiding therapeutic decisions. A systematic review and meta-analysis of existing literature of real-world expe

The paucity of high-quality studies to date indicates an unmet therapeutic need in the management of chronic pouchitis. Hence, identifying risk factors for chronic pouchitis is crucial for categorizing clinical profiles and predicting disease progression. Early recognition, even prior to IPAA surgery, is important to allow for interventions, such as counselling, risk assessment and postoperative management. These measures are crucial to enhance long-term patient outcomes and prevent complications.

Multiple risk factors for the development of chronic pouchitis have been investigated, including smoking history, male gender, extensive colitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and indication of IPAA surgery[11]. These risk factors were often derived from cohort or case-control studies. The risk factors reported in the literature have been inconsistent and sometimes contradictory. While systematic reviews and meta-analyses have focused on serological markers, microbiota, and extraintestinal manifestations as risk factors for the development of chronic pouchitis, none have evaluated the consistency of the previously reported clinical predictive risk factors which focused specifically on chronic pouchitis[12-14].

The aim of this study is to assess factors, including demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as pathology-based variables, for the development of chronic pouchitis after IPAA surgery in patients with UC. Our meta-analysis offers a more comprehensive and statistically robust assessment of these risk factors compared to previously published individual cohort or case-control studies. Identifying the risk factors of chronic pouchitis could inform more personalised patient management strategies, improve preoperative counselling, and potentially guide interventions to mitigate the risk of chronic pouchitis in patients undergoing IPAA surgery for UC in the future and improve long-term outcomes.

A systematic literature search of the Medline, EMBASE and PubMed databases was conducted to identify relevant articles published up to October 2023. Studies assessing the risk factors for the development of chronic pouchitis were searched using the Medical Subject Headings terms ‘ulcerative colitis’ and ‘pouchitis’, or ‘IPAA’, along with ‘risk factors’, ‘predictor’, ‘prevalence’ or ‘incidence’. The titles and abstracts of the identified studies were independently reviewed by two authors (Khoo E and Gilmore R) to exclude those that did not address the research questions of interest. Each study was assessed for relevance based on predefined inclusion criteria, which included factors such as study design, population, and the specific risk factors examined. Any discrepancies between the authors' assessments were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer if necessary (Begun J). The full text of the remaining articles was then read in full to determine if they contained relevant information pertaining to the risk factors for the development of chronic pouchitis. This comprehensive review process ensured that only studies with pertinent data were included in the final analysis.

The studies included in this meta-analysis were observational cohort studies and case control studies, that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Adult patients (aged 18 and older) who underwent IPAA surgery for UC; (2) Developed chronic pouchitis, either chronic antibiotic refractory pouchitis and/or chronic antibiotic responsive pouchitis; and (3) Provision of raw data or unadjusted odds ratio (OR) with either standard errors or confidence intervals (CI). Articles were excluded from the analysis if they focused on pediatric or other specific populations, lacked raw data or unadjusted odd ratios, or were unable to separate data for patients with Crohn’s disease of the pouch or acute pouchitis from patients with chronic pouchitis. When multiple publications from the same population were available, only data from the most recent and comprehensive report were included in the analysis to avoid duplication and ensure data integrity.

Data extraction was conducted by author (Khoo E) and independently verified by author (Griffin A) to ensure accuracy and minimize bias. Any disagreements between the two authors were resolved by consulting a third independent reviewer (Begun J). Once the data extraction was agreed upon, the final data was compiled in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States) format for statistical analysis.

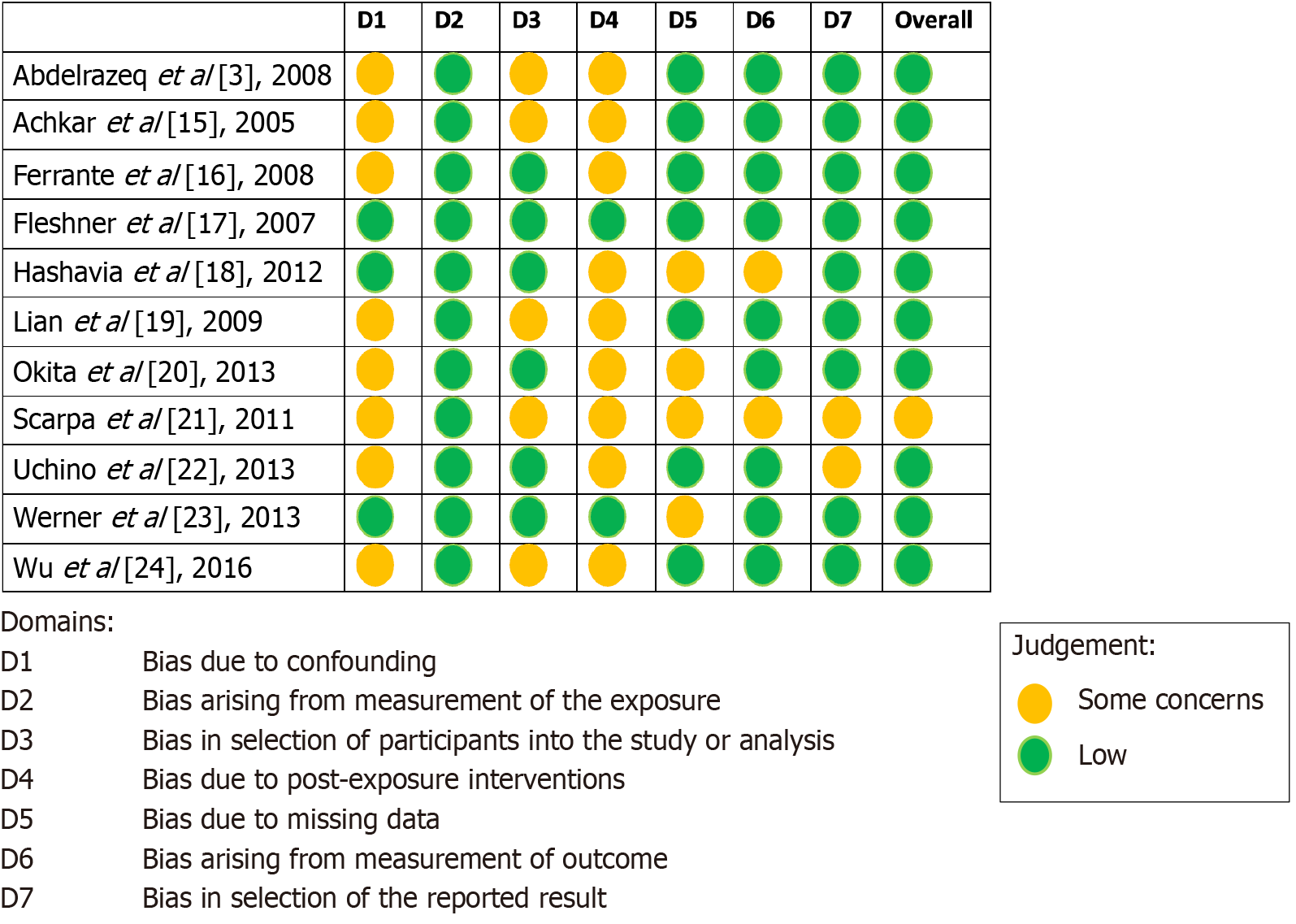

The Risk of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies of Exposure Effects (ROBINS-E) tool was employed to evaluate the risk of bias of each study. ROBINS-E assesses seven domains of bias including confounding, measurement of the exposure, selection of participants, post exposure interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes and selection of reported results. The risk of bias assessment was conducted independently by two authors (Khoo E and Gilmore R). Any conflicts were resolved by reaching a consensus, with reference to the original article when necessary.

All predictors of interest were binary categorical. The OR and 95%CI for chronic pouchitis with reference to non-chronic pouchitis (combined normal pouch and acute pouchitis) was calculated for each predictor separately for each study using 2 × 2 tables obtained from the included studies. If raw data in the form of 2 × 2 tables were not available but univariable OR and either 95%CI or standard errors were available, then the latter were used. Estimates were combined using a random effects model to calculate the pooled effect for each predictor. A weighted average effect size was calculated, with weights inversely proportional to the sum of the within-study and between-study variance. The restricted maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the variance. Forest plots including individual study effect size and CI as well as the pooled effect size and CI are presented for each predictor of interest. Between-study heterogeneity was estimated using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variability across studies due to heterogeneity. An I2 > 50% is considered high and suggests that a substantial portion of the variability in effect size is due to differences between studies. Statistical analysis was completed using Stata v17.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, United States) and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout inferential analysis.

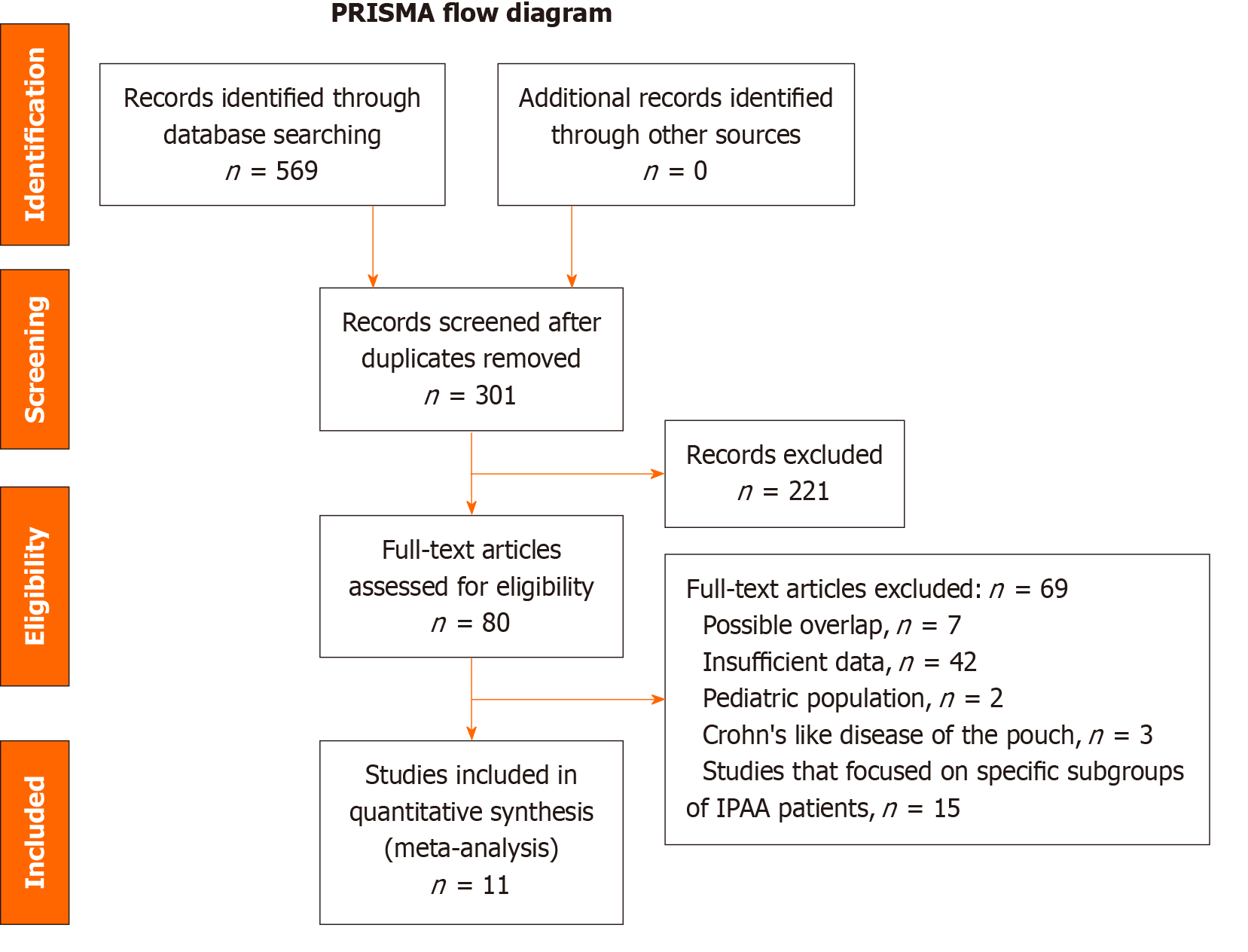

A total of 569 citations were identified from the database search. Duplicate articles, those studies that focused on specific subgroups of IPAA patients, and those with insufficient data were excluded. The flow diagram illustrating the studies excluded from this analysis is shown in Figure 1. Eleven articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. The final analysis included 3722 patients who underwent IPAA surgery. Among them, 3209 patients had either a normal pouch or acute pouchitis, while 513 had developed chronic pouchitis. The cohort with Crohn’s like disease of the pouch was excluded. The majority of the studies (10 out of 11) were conducted at single centres. All pouch cases were identified retrospectively, with some (7 out of 11) followed up prospectively. The baseline characteristics, including the study period, sample size, number of patients who developed chronic pouchitis, and the definition of chronic pouchitis, are summarized in Table 1[3,15-24].

| Ref. | Population | Number of IPAA | Normal pouch1 | Chronic pouchitis | Follow up period after IPAA | Definition of chronic pouchitis |

| Abdelrazeq et al[3], 2008 | York Hospital, Huddersfield Royal Infirmary, Derby Hospitals–prospective | 198 | 134 (68) | 29 (15) | Mean 64 months (range: 12-180 months) | Presence of active symptoms continuously for more than 4 weeks despite full dose of standard therapy or required more than 2 weeks of therapy every month for three consecutive months to achieve symptomatic control |

| Achkar et al[15], 2005 | Cleveland Clinic Foundation–prospective case control study | 120 | 40 (33) | 40 (33) | Mean 5.2 years | Presence of 4 or more episodes of pouchitis per year, or active symptoms lasting continuously for more than 4 weeks despite antibiotic therapy, or chronic antibiotic or anti-inflammatory therapy to control symptoms of pouchitis |

| Ferrante et al[16], 2008 | University Hospital Gasthuisberg–retrospective | 173 | 92 (53) | 33 (19) | Median 6.5 years (range: 34-9.9 years) | Presence of active symptoms lasted for more than 4 weeks, despite standard therapy |

| Fleshner et al[17], 2007 | Cedars-Sinar Medical Centre–prospective | 186 | 127 (68) | 23 (12) | Median 24 months (range: 3-117 months) | Required continuous antibiotic treatment for symptom relief or did not respond to antibiotic treatment |

| Hashavia et al[18], 2012 | Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Centre– prospective | 201 | - | 63 (31) | Mean 107 months | Presence of at least 4 weeks of persistent symptoms and dependent on prolonged therapy of more than two different antibiotics, or those who did not respond to antibiotics |

| Lian et al[19], 2009 | Cleveland Clinic Foundation–retrospective | 251 | 35 (14) | 29 (12) | - | Failed to respond to a 2-4 weeks course of a single antibiotic, or required therapy over 4 weeks with 2 antibiotics |

| Okita et al[20], 2013 | Mie University–retrospective | 231 | 165 (71) | 31 (13) | Median 1882.5 days (range: 31-4465 days) | Required long-term, continuous antibiotic therapy to maintain remission, or relapsing episodes (> 3 per year), or failed to respond to antibiotics |

| Scarpa et al[21], 2011 | University of Padova–prospective | 32 | - | 6 (19) | Median 23 months | No response to first line antibiotic therapy and required continuous antibiotic treatment for symptom relief or had a treatment resistant form |

| Uchino et al[22], 2013 | Hyogo College of Medicine–retrospective | 772 | 695 (90) | 29 (4) | Median 5.67 years (range: 152-10.81 years) | Failed to respond to a 4-week course of a single antibiotic, requiring prolonged therapy for ≥ 4 weeks with ≥ 2 antibiotics or topical corticosteroid therapy |

| Werner et al[23], 2013 | Tel Aviv Medical Centre–prospective | 36 | 10 (28) | 13 (36) | Follow up period was not mentioned | Required antibiotic or anti-inflammatory therapy for at least 4 weeks, or patients having more than 5 flares of pouchitis per year |

| Wu et al[24], 2016 | Cleveland Clinic Pouch Centre–prospective | 1564 | 181 (12) | 217 (14) | Median 9 years (range: 4-14 years) | Symptoms lasted for 4 weeks or more and failed to respond to a 4-week course of single antibiotic therapy |

Among the eleven studies, the size of the study populations varied significantly, ranging from 36 participants in the study by Werner et al[23] to 1564 participants in the study by Wu et al[24]. Most of these studies reported similar proportions of patients with chronic pouchitis as have been previously reported, with rates ranging from 11.5% to 31.3%[5]. However, there were notable exceptions: (1) Uchino et al[22]; and (2) Werner et al[23]. Uchino et al[22] reported a low incidence of chronic pouchitis at just 4%, with 90% of patients having a normal pouch. In contrast, Werner et al[23] reported a significantly higher incidence of chronic pouchitis at 36%, with only 10% of patients having a normal pouch. It is important to note that Werner et al[23] did not specify the study duration or follow-up period.

Each study was assessed for risk of bias using ROBINS-E tool, as shown in Figure 2[3,15-24]. None of the studies were found to have a high risk of bias; one out of eleven studies (Scarpa et al[21]) had a moderate risk, and the rest had a low overall risk of bias. The most common bias identified were bias due to confounding and bias due to post-exposure interventions.

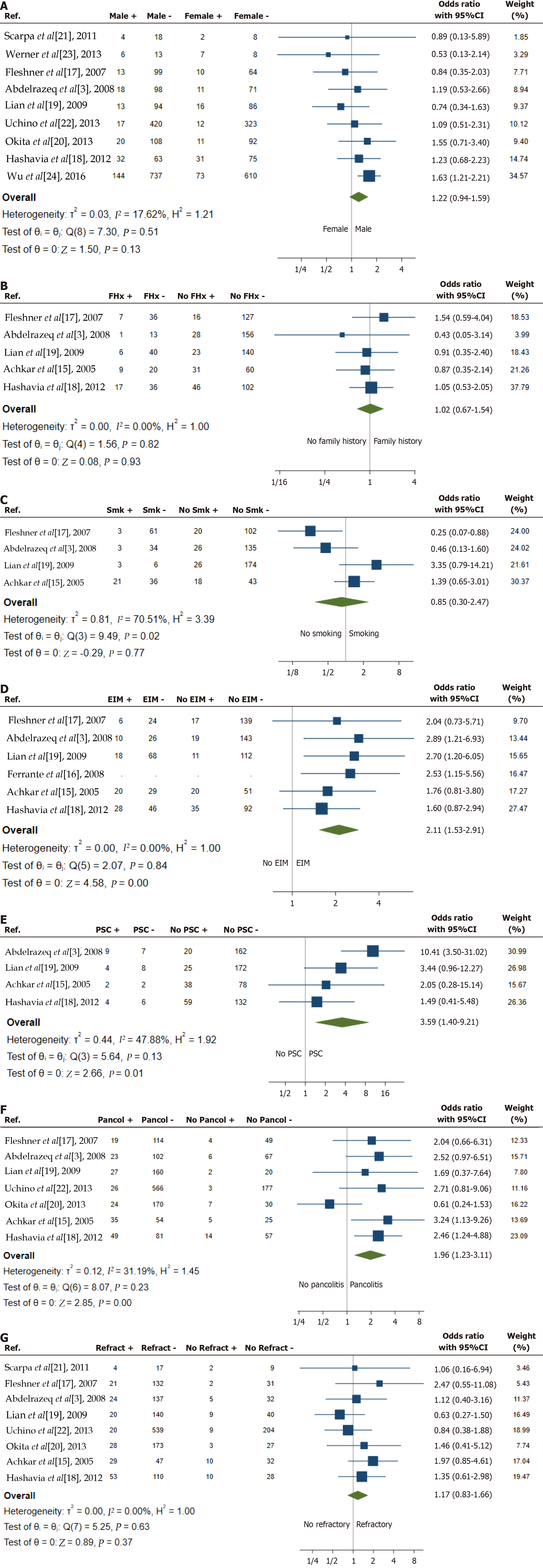

Baseline patient characteristics including male gender, family history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and smoking status were the most described risk factors for development of pouchitis (Figure 3A-C)[3,15,17-24]. Male gender was reported as a variable in nine of the studies. While the odds of chronic pouchitis tended to be higher in males, results were inconsistent and this difference did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.22, 95%CI: 0.94-1.59, P = 0.13, I2 = 18%). A family history of IBD was reported in five studies. The analysis indicated that the odds of developing chronic pouchitis were not significantly associated with a family history of IBD (OR = 1.02, 95%CI: 0.67-1.54, P = 0.93, I2 = 0%). Smoking status, comparing current smokers and ex-smokers to those who had never smoked, was described in four studies. The OR was 0.85 with a 95%CI of 0.30-2.47, favouring smoking as a potential protective factor for chronic pouchitis. However, the P value was not significant (P = 0.77) and there was high heterogeneity (I2 = 71%, P = 0.02), with two studies suggesting that chronic pouchitis is more likely in non-smokers, and two studies indicating it is more likely in smokers (combined active and former smokers). This high heterogeneity means that the combined estimate is of limited value.

Immune-related extraintestinal manifestations[25], including joint conditions (sacroiliitis, ankylosing spondylitis and peripheral arthritis), PSC, eye conditions (episcleritis and uveitis) and skin conditions (pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum) were described in six studies (Figure 3D and E)[3,15-19]. The odds of chronic pouchitis were higher in individuals with extra-intestinal manifestations (OR = 2.11, 95%CI: 1.53-2.91, P < 0.001), and this finding was consistent across all six included studies (I2 = 0%). PSC, in particular, was found to have the highest OR among all risk factors analysed. The OR for chronic pouchitis in individuals with PSC was 3.59, with a 95%CI of 1.40-9.21 (P = 0.01). Although all four included studies showed an increase in the risk of chronic pouchitis, there was heterogeneity in the magnitude of the effect (I2 = 48%).

Distribution of colitis prior to surgery was reported in seven studies (Figure 3F)[3,15,17-20,22]. The odds of chronic pouchitis were higher in people with pancolitis (OR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.23-3.11, P < 0.001, I2 = 31%). While a single study found lower odds of chronic pouchitis in individuals with pancolitis, this did not reach statistical significance. This discrepancy could be due to chance or differences in population or methodology. The indication for IPAA surgery [refractory disease compared with other indications (acute severe colitis, colonic dysplasia or cancer)] was described in eight studies (Figure 3G)[3,15,17-22]. The odds of chronic pouchitis (OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 0.83-1.66, P = 0.37, I2 = 0%) were not significantly associated with the indication for surgery.

One study suggested that pre-operative use of biologic agents might be associated with a lower risk of chronic pouchitis, although this finding was not statistically significant (OR = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.05-3.00, P = 0.361). Another study reported a possible association between post-operative infection and chronic pouchitis, but this finding was also not statistically significant (OR = 1.41, 95%CI: 0.45-4.46, P = 0.56). Due to the limited number of studies investigating these factors, a meta-analysis could not be performed.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to evaluate risk factors associated with the development of chronic antibiotic-dependent and antibiotic-refractory pouchitis in patients who underwent IPAA surgery for UC. Eleven studies, comprising a total of 3722 patients, met the inclusion criteria for the final analysis. Within this cohort, 513 patients (13.8%) developed chronic pouchitis, while 3209 patients (86.2%) did not. The latter group comprised patients with a normal pouch and those with acute pouchitis or a history of acute pouchitis; cases resembling Crohn's disease of the pouch were excluded.

Our study corroborates previous findings that extraintestinal manifestations, specifically PSC, are risk factors for chronic pouchitis. This aligns with Hata et al[14], who reported an association between both extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) and PSC with overall pouchitis, particularly chronic pouchitis. Similarly, Penna et al[26] observed a cumulative pouchitis risk of 79% in UC patients with PSC, compared to 46% in those without PSC over a ten-year post-IPAA follow up. Additionally, we identified extensive colitis as a pre-operative risk factor for chronic pouchitis, suggesting disease severity may influence its development. In contrast, extraintestinal manifestations, including PSC, and pancolitis did not impact the risk of Crohn's disease of the pouch (CDP)[27].

Other factors, such as male gender and refractory UC as a surgical indication, demonstrated a non-significant trend towards increased chronic pouchitis risk. Family history of IBD did not alter the risk. While smoking may increase acute pouchitis incidence[28], the exposure to cigarette smoking, whether active or former, exhibited a protective trend against chronic pouchitis in two out of four of the studies, albeit non-significant with high heterogeneity between studies. In comparison, Fadel et al[27] reported that smoking and family history of IBD were associated with CDP development. A surgical indication of dysplasia or colon cancer was protective against CDP[27], suggesting distinct pathogenic mecha

The precise mechanisms underlying chronic pouchitis remain elusive. However, accumulating evidence suggests that certain serological markers, microbial dysbiosis and genetic polymorphisms may contribute to its development. This condition represents a dysregulated mucosal immune response to intestinal microbiome. High titres of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and the presence of microsomal antibody are positively associated with chronic pouchitis[12,29]. Elevated serum immunoglobulin G 4 (IgG4) levels and an increased number of IgG4 expressing plasma cell of more than 10 per high power field within pouch biopsies, have also been identified as risk factors for chronic pouchitis, independent of autoimmune serological markers, when compared to non-chronic pouchitis cohort[29]. Microbiota studies have suggested that mucosal toll like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 expression, as well as increased levels of mucosa associated Clostridium spp, are associated with chronic pouchitis[21]. Carrier trait analysis revealed that the presence of TLR9-1237C and CD14-260T alleles simultaneously occurs significantly higher in patients with chronic pouchitis[21]. Haplotyping of TLR9 has shown that a C allele at TLR9-1237 and an A allele at TLR9+2848 are more frequently observed in patients with chronic pouchitis[30]. These features collectively suggest that a dysregulated immune response to commensal bacteria may predispose individuals to chronic pouchitis. Furthermore, these combined markers could potentially be used to identify a subgroup of IPAA patients at increased risk of developing chronic pouchitis.

Pre-operative predictive factors for chronic pouchitis remain inconclusive. Several studies have investigated the association between different types of pre-operative therapies and chronic pouchitis development, but no significant association has been established. While Okita et al[20] suggested a potential risk factor for chronic pouchitis associated with high pre-operative steroid doses (accumulative dose of 500 mg or more per month), the overall effect of pre-operative steroid use on the risk of chronic pouchitis remains uncertain. Similarly, the role of pre-operative immunomodulators and biologic therapies in chronic pouchitis development is unclear. While some studies have suggested a potential link, others have found no association. For example, Esckilsen et al[31] reported a possible increased risk with vedo

Post-operative factors were also examined as potential predictors of chronic pouchitis. Studies found that complications following surgery, particularly anastomotic leaks or separations, were linked to a higher risk of developing chronic pouchitis[32]. However, the exact relationship between these complications and chronic pouchitis remains ambiguous. Some experts suggest that patients with anastomotic complications, especially those with additional risk factors, might benefit from preventive treatments for chronic pouchitis. Additionally, imaging evidence revealed that excess fat around the pouch, including mesenteric, visceral, and subcutaneous fat, was strongly associated with chronic pouchitis[33]. Researchers proposed that this fat accumulation might reflect ongoing inflammation and could potentially disrupt blood flow to the pouch, making it a valuable indicator of future pouch health. In contrast, post-operative use of immunomodulators or biologic therapies[34], as well as factors like anal pressure and soiling[31], were not found to increase the risk of chronic pouchitis.

The strengths of our study include the well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria with a large sample size of chronic pouchitis patients. The overall risk of bias was also deemed low in the eleven included studies. Unfortunately, numerous articles meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded due to incomplete raw datasets. Also, the studies exhibited a substantial range in study population characteristics and follow up duration that range from median of 23 months to 9 years, contributing to heterogeneity across the studies. All these limitations contribute to overall study’s validity, generalizability and the strength of its findings.

This study identified extraintestinal manifestations, particularly PSC, and extensive colitis as the strongest predictors of chronic pouchitis development in UC patients undergoing IPAA surgery. Conversely, gender, smoking history and IPAA surgical indication did not significantly influence chronic pouchitis incidence. Given the association between these factors and chronic pouchitis, prospective studies are warranted to further elucidate their pathophysiological mechanisms and inform potential targeted interventions. By unravelling these pathways, we can develop targeted and earlier interventions to prevent or treat chronic pouchitis in high-risk patients.

Key risk factors for chronic pouchitis: (1) PSC: This chronic biliary condition, which commonly occurs alongside UC, increases the risk of chronic pouchitis after IPAA surgery; (2) EIMs of IBD: These are symptoms of IBD that occur outside the intestines, such as joint pain (arthritis), skin problems (erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum), and eye inflammation (uveitis). Having a history of EIMs can increase the risk of chronic pouchitis; and (3) Extensive colitis or pancolitis: The distribution of colitis could reflect the severity of disease and increase the risk of chronic pouchitis after IPAA sur

Importance of identifying risk factors: (1) Patient counselling: Healthcare providers can counsel patients about their individual risk of developing pouchitis after IPAA surgery; (2) Early detection and intervention: Patients with risk factors can be monitored more closely for signs of pouchitis, allowing for early intervention and potentially preventing the development of chronic pouchitis; and (3) Research: Further research into these risk factors can help to better understand the causes of pouchitis and develop more effective prevention and treatment strategies.

| 1. | Akiyama S, Rai V, Rubin DT. Pouchitis in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Intest Res. 2021;19:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fazio VW, Kiran RP, Remzi FH, Coffey JC, Heneghan HM, Kirat HT, Manilich E, Shen B, Martin ST. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis: analysis of outcome and quality of life in 3707 patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257:679-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abdelrazeq AS, Kandiyil N, Botterill ID, Lund JN, Reynolds JR, Holdsworth PJ, Leveson SH. Predictors for acute and chronic pouchitis following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:805-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, Ardizzone S, Armuzzi A, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Burisch J, Gecse KB, Hart AL, Hindryckx P, Langner C, Limdi JK, Pellino G, Zagórowicz E, Raine T, Harbord M, Rieder F; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, Diagnosis, Extra-intestinal Manifestations, Pregnancy, Cancer Surveillance, Surgery, and Ileo-anal Pouch Disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1446] [Cited by in RCA: 1298] [Article Influence: 162.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bresteau C, Amiot A, Kirchgesner J, de'Angelis N, Lefevre JH, Bouhnik Y, Panis Y, Beaugerie L, Allez M, Brouquet A, Carbonnel F, Meyer A. Chronic pouchitis and Crohn's disease of the pouch after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: Incidence and risk factors. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:1128-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dalal RL, Shen B, Schwartz DA. Management of Pouchitis and Other Common Complications of the Pouch. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:989-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bär F, Kühbacher T, Dietrich NA, Krause T, Stallmach A, Teich N, Schreiber S, Walldorf J, Schmelz R, Büning C, Fellermann K, Büning J, Helwig U; German IBD Study Group. Vedolizumab in the treatment of chronic, antibiotic-dependent or refractory pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:581-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Madiba TE, Bartolo DC. Pouchitis following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: incidence and therapeutic outcome. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2001;46:334-337. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Khoo E, Lee A, Neeman T, An YK, Begun J. Comprehensive systematic review and pooled analysis of real-world studies evaluating immunomodulator and biologic therapies for chronic pouchitis treatment. JGH Open. 2023;7:899-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Travis S, Silverberg MS, Danese S, Gionchetti P, Löwenberg M, Jairath V, Feagan BG, Bressler B, Ferrante M, Hart A, Lindner D, Escher A, Jones S, Shen B; EARNEST Study Group. Vedolizumab for the Treatment of Chronic Pouchitis. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1191-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shen B, Achkar JP, Connor JT, Ormsby AH, Remzi FH, Bevins CL, Brzezinski A, Bambrick ML, Fazio VW, Lashner BA. Modified pouchitis disease activity index: a simplified approach to the diagnosis of pouchitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:748-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Singh S, Sharma PK, Loftus EV Jr, Pardi DS. Meta-analysis: serological markers and the risk of acute and chronic pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:867-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Angriman I, Scarpa M, Castagliuolo I. Relationship between pouch microbiota and pouchitis following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9665-9674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hata K, Okada S, Shinagawa T, Toshiaki T, Kawai K, Nozawa H. Meta-analysis of the association of extraintestinal manifestations with the development of pouchitis in patients with ulcerative colitis. BJS Open. 2019;3:436-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Achkar JP, Al-Haddad M, Lashner B, Remzi FH, Brzezinski A, Shen B, Khandwala F, Fazio V. Differentiating risk factors for acute and chronic pouchitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:60-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ferrante M, Declerck S, De Hertogh G, Van Assche G, Geboes K, Rutgeerts P, Penninckx F, Vermeire S, D'Hoore A. Outcome after proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:20-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fleshner P, Ippoliti A, Dubinsky M, Ognibene S, Vasiliauskas E, Chelly M, Mei L, Papadakis KA, Landers C, Targan S. A prospective multivariate analysis of clinical factors associated with pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:952-958; quiz 887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hashavia E, Dotan I, Rabau M, Klausner JM, Halpern Z, Tulchinsky H. Risk factors for chronic pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a prospective cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1365-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lian L, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Hammel J, Remzi FH, Shen B. Evaluation of association between precolectomy thrombocytosis and the occurrence of inflammatory pouch disorders. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1912-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Okita Y, Araki T, Tanaka K, Hashimoto K, Kondo S, Kawamura M, Koike Y, Otake K, Fujikawa H, Inoue M, Ohi M, Inoue Y, Uchida K, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M. Predictive factors for development of chronic pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis. Digestion. 2013;88:101-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Scarpa M, Grillo A, Pozza A, Faggian D, Ruffolo C, Scarpa M, D'Incà R, Plebani M, Sturniolo GC, Castagliuolo I, Angriman I. TLR2 and TLR4 up-regulation and colonization of the ileal mucosa by Clostridiaceae spp. in chronic/relapsing pouchitis. J Surg Res. 2011;169:e145-e154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Matsuoka H, Bando T, Takesue Y, Tomita N. Clinical features and management of pouchitis in Japanese ulcerative colitis patients. Surg Today. 2013;43:1049-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Werner L, Sturm A, Roggenbuck D, Yahav L, Zion T, Meirowithz E, Ofer A, Guzner-Gur H, Tulchinsky H, Dotan I. Antibodies against glycoprotein 2 are novel markers of intestinal inflammation in patients with an ileal pouch. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e522-e532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wu XR, Ashburn J, Remzi FH, Li Y, Fass H, Shen B. Male Gender Is Associated with a High Risk for Chronic Antibiotic-Refractory Pouchitis and Ileal Pouch Anastomotic Sinus. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:631-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mathis KL, Dozois EJ, Larson DW, Cima RR, Sarmiento JM, Wolff BG, Heimbach JK, Pemberton JH. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and liver transplantation for ulcerative colitis complicated by primary sclerosing cholangitis. Br J Surg. 2008;95:882-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Penna C, Dozois R, Tremaine W, Sandborn W, LaRusso N, Schleck C, Ilstrup D. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis occurs with increased frequency in patients with associated primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 1996;38:234-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fadel MG, Geropoulos G, Warren OJ, Mills SC, Tekkis PP, Celentano V, Kontovounisios C. Risks Factors Associated with the Development of Crohn's Disease After Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis for Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:1537-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fleshner P, Ippoliti A, Dubinsky M, Vasiliauskas E, Mei L, Papadakis KA, Rotter JI, Landers C, Targan S. Both preoperative perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and anti-CBir1 expression in ulcerative colitis patients influence pouchitis development after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:561-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Seril DN, Yao Q, Lashner BA, Shen B. Autoimmune features are associated with chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:110-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lammers KM, Ouburg S, Morré SA, Crusius JB, Gionchett P, Rizzello F, Morselli C, Caramelli E, Conte R, Poggioli G, Campieri M, Peña AS. Combined carriership of TLR9-1237C and CD14-260T alleles enhances the risk of developing chronic relapsing pouchitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7323-7329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Esckilsen S, Kochar B, Weaver KN, Herfarth HH, Barnes EL. Very Early Pouchitis Is Associated with an Increased Likelihood of Chronic Inflammatory Conditions of the Pouch. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:3139-3147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Koike Y, Uchida K, Inoue M, Nagano Y, Kondo S, Matsushita K, Okita Y, Toiyama Y, Araki T, Kusunoki M. Early first episode of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for pediatric ulcerative colitis is a risk factor for development of chronic pouchitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1788-1793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hoda KM, Collins JF, Knigge KL, Deveney KE. Predictors of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a retrospective review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:554-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Gao XH, Yu GY, Khan F, Li JQ, Stocchi L, Hull TL, Shen B. Greater Peripouch Fat Area on CT Image Is Associated with Chronic Pouchitis and Pouch Failure in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:3660-3671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |