INTRODUCTION

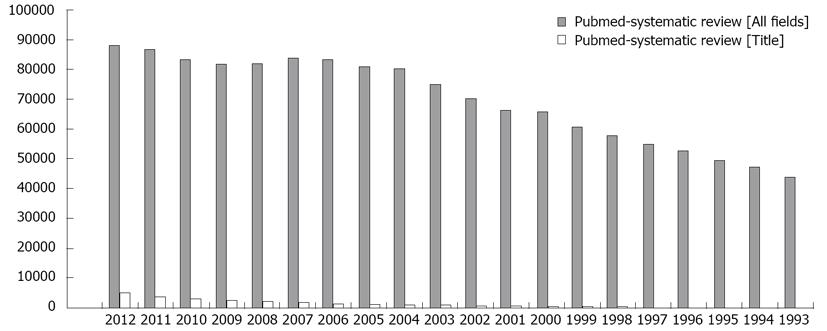

Nowadays, there is an increasing trend in the number of systematic reviews over time (Figure 1). This phenomenon is primarily because well-conducted systematic reviews can provide the best-quality research evidence for clinicians by combining the results of all available data. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement, an updated version of Quality of Reporting of Meta-analysis statement published in 1999[1], has been recently developed to improve the quality of reporting systematic reviews[2]. More recently, an international registry of systematic review protocols is being established by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination to further increase the transparency of the review process and outcomes[3]. In spite of these methodological advances, little attention has been paid for the issue regarding how to find duplicates in systematic reviews. On the basis of the survey and systematic reviews by our team and others, this review primarily aims to outline the prevalence, significance, and classification of duplicates, and to describe the method regarding how to find duplicates in a systematic review.

Figure 1 Trend in the publication of systematic reviews over time.

PREVALENCE

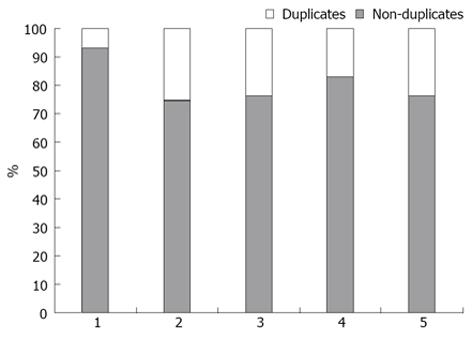

In this section, the prevalence of duplicates reported in four systematic reviews conducted by our team using more than three databases is summarized[4-7] (Figure 2). The reason why only the literature search results from our published papers are primarily reviewed is primarily because of the reliability and accuracy of data regarding the duplicates in our systematic reviews. Additionally, other systematic reviews using only one database are not analyzed[8-11]. Overall, the prevalence of duplicates ranges from 7% to 25% among the three different databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library).

Figure 2 The prevalence of duplicates reported in four systematic reviews conducted by our team.

1: Qi JGH (2013); 2: Bai JGH (2013); 3: Qi AJM (2013); 4: Qi PlosOne (2013) PVT; 5: Qi PlosOne (2013) BCS.

On the other hand, several investigators have evaluated the duplicate publication in different journals or specialties. Arrivé et al[12] searched 362 original research articles published in Radiology during 2001, but only two redundant publications were found among these articles. Durani also found that only less than 1% of articles had some degree of redundancy in British Journal of Plastic Surgery and Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery during 2000[13]. By comparison, Schein and Paladugu screened 660 original articles published in the journals Surgery, The British Journal of Surgery and Archives of Surgery during 1998 and found that about 14% of these papers had some potential form of a redundant publication[14]. Recently, our systematic analysis demonstrated a relatively high prevalence of covert duplicate publications among articles on Budd-Chiari syndrome in China (10%, 184/1914)[6]. Notably, we also found a significantly higher prevalence of covert duplicate publications in Science Citation Index journals, compared to Chinese language journals.

SIGNIFICANCE

The most detrimental effect of duplicates on the systematic review is to introduce the potential bias and to influence the reliability of the conclusion. In a case study by Tramèr et al[15], all published randomized controlled trials, which compared the prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy between ondansetron and placebo, no treatment, or other antiemetics on nausea and vomiting after general anesthesia, were retrieved by searching Medline, EMBASE, and Biological Abstracts databases. The investigators found a high prevalence of duplicate papers (17% of randomized controlled trials and 28% of patient data were duplicated). More importantly, if duplicated data were included into the meta-analysis, the antiemetic efficacy of ondansetron would be overestimated by 23%. In addition, covert duplicate publications can cause some serious harm in routine clinical practice[16,17], such as violation of the ethics of scientific publications and inflation of medical knowledge.

CLASSIFICATION

Several different classifications or patterns of duplicates have been proposed.

First, a traditional grading system includes three types of redundant publications, as follows: (1) dual publication (identical material, methods, and conclusions); (2) potentially dual (almost identical material, methods, and conclusions); and (3) salami slicing (suspected study represents a part of, continuation of, or partial repetition of the index article)[14]. This grading system has been widely used by journal editors and peer reviewers to identify the redundant publications[14].

Second, a Switzerland group has recently identified six different patterns of duplicate publications by analyzing 56 systematic reviews in anesthesia and analgesia[18]. According to the samples and outcomes, they include: (1) identical samples and identical outcomes; (2) same as 1 but several duplicates assembled; (3) identical samples and different outcomes; (4) increasing samples and identical outcomes; (5) decreasing samples and identical outcomes; and (6) different samples and different outcomes. Systematic review authors should be encouraged to use this classification to unearth duplications and make them public.

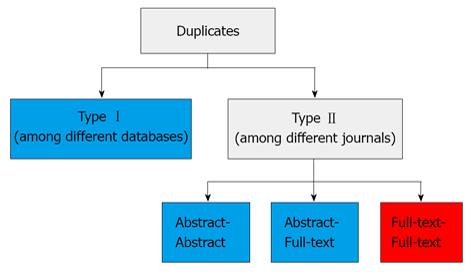

Finally, more recently, our group has further divided the duplicates into two main types by analyzing the literature regarding portal vein thrombosis and Budd-Chiari syndrome in systematic reviews[7] (Figure 3). Type I duplicates would be considered, if one paper was simultaneously recorded in one database twice or more times or in two or three databases[7]. Type II duplicates would be considered, if one study was published in different journals or issues[7]. The simple classification is primarily dependent on the origin of redundant publications (different databases or different journals). Certainly, the type I duplicates are reasonable. In addition, according to the type of publication, type II duplicates are further classified as Abstract-Abstract, Abstract-Full text and Full text-Full text[7]. The first two types are often permitted, but the last type is unethical and considered as redundant publication.

Figure 3 Classification of duplicates proposed by our team.

Types of duplicates signed by blue are often permitted, but types of duplicates signed by red are unethical.

HOW TO FIND DUPLICATES?

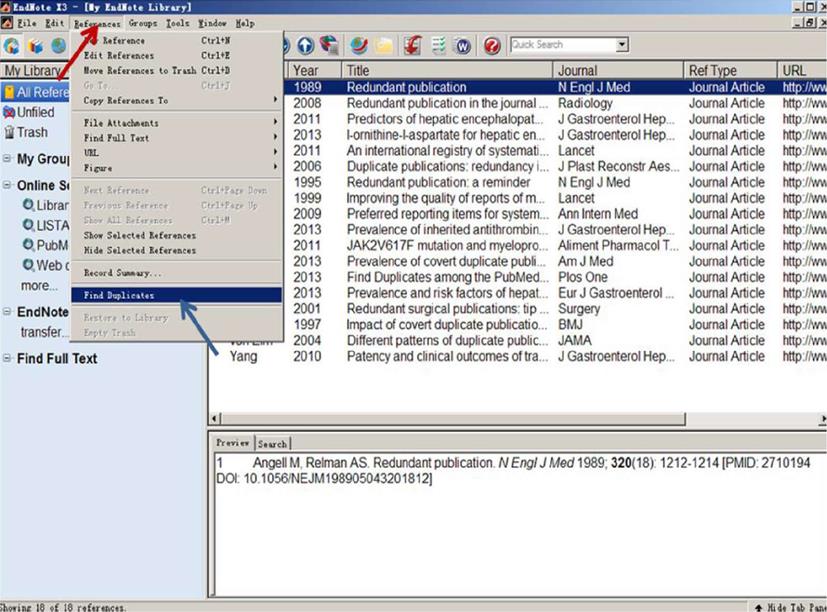

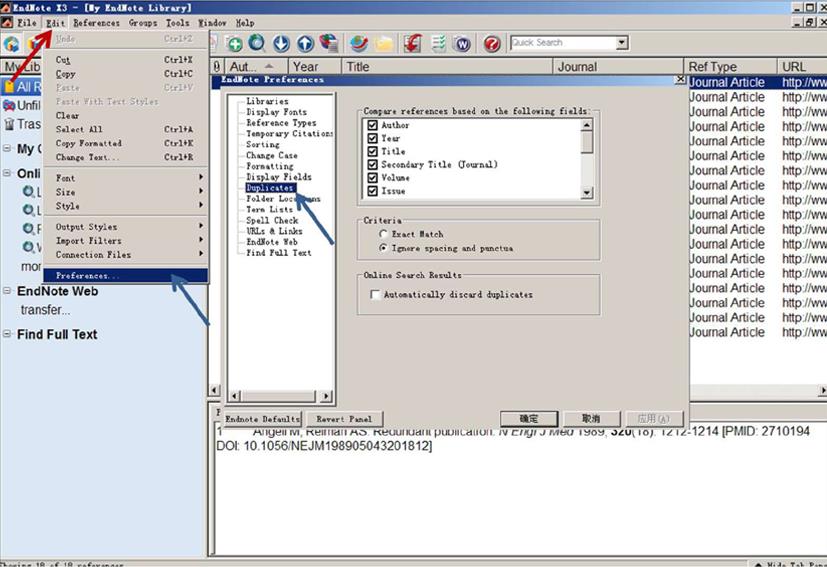

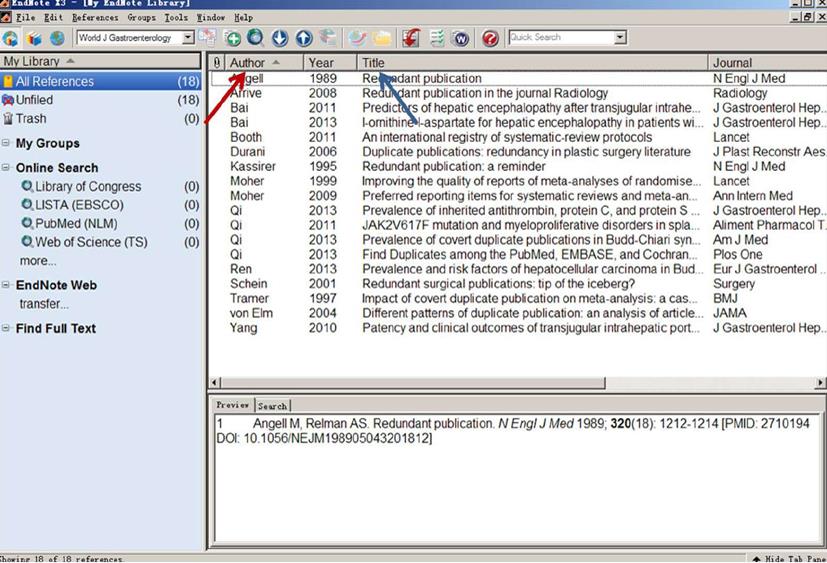

Although it is a critical issue to find duplicates, no consensus regarding how to find duplicates has been reached yet. In an analysis of previous systematic reviews, the investigators described a decision tree to mutually identify the patterns of duplicate publications, but did not introduce any methods to find duplicates[18]. Our group attempted to design a pragmatic strategy of combining auto- and hand-searching duplicates in systematic reviews. Briefly, this strategy includes two main steps as follows[7]. First, the review authors can use “Find Duplicates” command on the “References” menu to automatically identify the duplicates in the Endnote library (Figure 4). Notably, before auto-searching duplicates, the “Preferences” command on the “Edit” menu could be used to edit the characteristics of duplicates (Figure 5). Additionally, all identified duplicates should be confirmed by review authors. Second, the remaining literatures are ordered according to the first author’s name and title (Figure 6). Review authors can mutually identify the duplicates by the same author and title. Certainly, further confirmation of accuracy of these duplicates should be necessary. Additionally, we have to acknowledge that not all duplicates would be found by the above-mentioned method, especially when the first authors and titles are different between two potential duplicate papers. Thus, further improvement of this method to find duplicates should be warranted.

Figure 4 Use of “Find Duplicates” command under the “References” menu.

Red arrow indicates the “References” menu. Blue arrow indicates the “Find Duplicates” command.

Figure 5 Use of the “Preferences” command under the “Edit” menu.

Red arrow indicates the “Edit” menu. Blue arrow indicates the “Preferences” and “Duplicates” commands.

Figure 6 Ordering the literatures according to the first author’s name and title.

Red arrow indicates that literatures are ordered according to the author’s name. Blue arrow indicates that literatures are ordered according to the title.

CONCLUSION

As we have known, literature search results are often variable across different databases, thereby potentially leading to heterogeneous conclusions. Therefore, it has been recommended that multiple databases should be adopted to search the relevant literatures in a systematic review[19]. In this case, further work is very necessary to find duplicates among different databases. However, few systematic reviews reported the detailed information regarding how to find duplicates. A preliminary method to find duplicates is established, but its usefulness and convenience need to be further confirmed.

P- Reviewers: Eslick GD, Sun ZH S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Lu YJ