Published online May 26, 2013. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v1.i1.27

Revised: April 16, 2013

Accepted: May 9, 2013

Published online: May 26, 2013

Processing time: 83 Days and 12.4 Hours

AIM: To summarize the evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the rehabilitation effects of recreational activities.

METHODS: Studies were eligible if they were RCTs. Studies included one treatment group in which recreational activity was applied. We searched the following databases from 1990 to May 31, 2012: MEDLINE via PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Ichushi-Web. We also searched all Cochrane Databases and Campbell Systematic Reviews up to May 31, 2012.

RESULTS: Eleven RCTs were identified, which included many kinds of target diseases and/or symptoms such as stroke, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, acquired brain injury, chronic non-malignant pain, adolescent obesity, high-risk pregnancy, and the frail elderly. Various intervention methods included gaming technology, music, dance, easy rider wheelchair biking, leisure education programs, and leisure tasks. The RCTs conducted have been of relatively low quality. A meta-analysis (pooled sample; n = 44, two RCTs) for balance ability using tests such as “Berg Balance Scale” and “Timed Up and Go Test” based on game intervention revealed no significant difference between interventions and controls. In all other interventions, there were one or more effects on psychological status, balance or motor function, and adherence as primary or secondary outcomes.

CONCLUSION: There is a potential for recreational activities to improve rehabilitation-related outcomes, particularly in psychological status, balance or motor function, and adherence.

Core tip: This is the first systematic review of the effectiveness of rehabilitation based on recreational activities. There is a potential for recreational activities to improve rehabilitation-related outcomes, particularly in psychological status (depression, mood, emotion, and power), balance or motor function, and adherence (feasibility and attendance). To most effectively assess the potential benefits of recreational activities for rehabilitation, it will be important for further research to utilize (1) randomized controlled trials methodology (person unit or cluster unit) when appropriate; (2) an intervention dose; (3) a description of adverse effects and withdrawals; and (4) the cost of recreational activities.

- Citation: Kamioka H, Tsutani K, Yamada M, Park H, Okuizumi H, Honda T, Okada S, Park SJ, Kitayuguchi J, Handa S, Mutoh Y. Effectiveness of rehabilitation based on recreational activities: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal 2013; 1(1): 27-46

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v1/i1/27.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v1.i1.27

Recreational activity is anything that is stimulating and rejuvenating for an individual. Some people may enjoy nature hikes, others may enjoy playing the guitar. The idea behind these activities is to expand the mind and body in a positive, healthy way. The best reason to take part in these activities is that they will slow the aging process by helping to lessen or eliminate stress[1]. A dictionary describes “recreation” as “the fact of people doing things for enjoyment, when they are not working”[2]. However, there are various views about what constitutes a recreational activity and there is no fixed consensus.

A systematic review (SR) of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) based on recreational and leisure activity reported some beneficial effects such as improvement in quality of life, as well as health-promoting, educational and therapeutic effects[3]. Three RCTs adopted for this review evaluated appreciation of performed music[4], entertainment using an easy rider wheelchair bike[5], and leisure tasks[6] as the intervention method. In the present study, we assumed that recreational activity is defined broadly as a physical activity with a strong element of pleasure or enjoyment.

Stroke is a disease that typically requires rehabilitation and has been described as a worldwide epidemic[7]. Many stroke patients suffer from sensory, motor and cognitive impairment as well as a reduced ability to perform self care and to participate in social and community activities[8]. Standardized repetitive task training has been shown to be effective in some aspects of rehabilitation, such as improving walking distance and speed[9]. Over the years, virtual reality (VR) and interactive video gaming (IVG) have emerged as new treatment approaches in stroke rehabilitation. In particular, commercial gaming consoles are being rapidly adopted in clinical and nursing settings. A recent SR of stroke rehabilitation studies reported that the use of VR and IVG may be beneficial in improving arm function and activities of daily living (ADL) function when compared with the same dose of conventional therapy, although there was insufficient evidence to reach a conclusion about the effect of VR and IVG on grip strength or gait speed[10].

The current study has shown that even a short duration of Wii play can provide an effective adjunct to standard rehabilitation for fall prevention, although a “Wii only” training approach is not being advocated[11]. The “enjoyment” factor is an important one that may aid adherence to training for rehabilitation[12].

Low back pain is also a disease that requires rehabilitation and is the most common reason for use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States[13]. A SR of RCTs into alternative therapy (i.e., spa and balneotherapy) targeting the relief of lower back pain reported that even though the data are scarce, there was encouraging evidence suggesting that these therapies may be effective[14].

Over the years, recreational activity and relaxation in a forest environment called “forest therapy” or “Shinrin-yoku” (forest-air bathing and forest-landscape watching, walking, etc.), have become a kind of climate therapy or nature therapy and are popular methods for many urban people with mentally stressful situations[15]. The fields of preventive and alternative medicine have also shown an interest in the therapeutic effects of forest therapy[16]. A study reported that forest environments may contribute to the maintenance of health and well-being by, for example reducing hostility and depression which are risk factors for coronary heart diseases, or by improving overall emotions, particularly among populations with poor mental health[17]. In addition, a recent study reported that forest bathing trips increase natural killer (NK) cell activity, which was mediated by increases in the number of NK cells and by the levels of intracellular anti-cancer proteins and phytoncides released from trees. The decreased production of stress hormones may also partially contribute to the increased NK cell activity[18].

It is well known in research design that evidence grading is highest for a SR with meta-analysis of RCTs. Although many studies have reported the rehabilitation effects of recreational activities, there is no SR of evidence based on RCTs. The objective of this review was to summarize the evidence from RCTs on the rehabilitation effects of recreational activities.

Types of studies: Studies were eligible if they were RCTs.

Types of participants: There was no restriction on patients.

Types of intervention and language: Studies included at least one treatment group in which recreation activity was applied. The definition of the recreational activity is complex, but, in this study, it describes a specific exercise item. Specifically, any kind of recreational activity (not only dynamic activities but also musical appreciation or playing, painting, hand-craft, etc.) was permitted and defined as an intervention. However, we excluded comprehensive exercise interventions such as walking, jogging, Tai chi, Yoga, stretching, and strength training. There was no restriction on the basis of language.

Types of outcome measures: We focused on rehabilitation effects. The World Health Organization states that rehabilitation of people with disabilities is a process aimed at enabling them to reach and maintain their optimal physical, sensory, intellectual, psychological and social functional levels[19]. Rehabilitation provides disabled people with the tools they need to attain independence and self-determination. In this study, beneficial outcome measures included cognitive function, physical function, and pain-relief. We did not specify secondary outcomes but instead estimated items as primary outcomes if an article treated them as rehabilitation effects.

Bibliographic database: We searched the following databases from 1990 to May 31, 2012: MEDLINE via PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Ichushi Web (in Japanese), and the Western Pacific Region Index Medicus (WPRIM). The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recommended uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals in 1993. We selected articles published (that included a protocol) since 1990, because it appeared that the ICMJE recommendation had been adopted by the relevant researchers and had strengthened the quality of reports.

We also searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Cochrane Reviews), the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (Other Reviews), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Clinical Trials or CENTRAL), the Cochrane Methodology Register (Methods Studies), the Health Technology Assessment Database (Technology Assessments), the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (Economic Evaluations), About The Cochrane Collaboration databases (Cochrane Groups) and Campbell Systematic Reviews (the Campbell Collaboration), and the All Cochrane all up to May 31, 2012.

All searches were performed by two specific searchers (hospital librarians) who were qualified in medical information handling, and who had sophisticated skills in the searching of clinical trials.

Search strategies: The special search strategies contained the elements and terms for MEDLINE, CINAHL, Web of Science, Ichushi Web, WPRIM, All Cochrane databases, and Campbell Collaboration (Table 1). Only keywords about interventions were used for the searches. First, titles and abstracts of identified published articles were reviewed in order to determine the relevance of the articles. Next, references in relevant studies and identified RCTs were screened.

| 1 MEDLINE |

| #1 Search “Recreation” [MeSH Major Topic] |

| #2 Search “Recreation Therapy” [MeSH Major Topic] |

| #3 Search “Rehabilitation” [MeSH Major Topic] |

| #4 Search “Treatment Outcome” [MeSH Terms] |

| #5 Search (#1) OR #2 |

| #6 Search (#3) OR #4 |

| #7 Search (#5) AND #6 |

| #8 Search (#5) AND #6 Filters: Publication date from 1990-01-01 to 2012-04-30 |

| #9 Search (#5) AND #6 Filters: Publication date from 1990-01-01 to 2012-04-30; Humans |

| #10 Search (#5) AND #6 Filters: Publication date from 1990-01-01 to 2012-04-30; Humans; Randomized Controlled Trial |

| 2 CINHAL |

| #1 TX recreation |

| #2 (MH “Recreation+”) OR (MH “Recreational Therapy”) |

| #3 #1 or #2 |

| #4 TX rehabilitation |

| #5 (MH “Rehabilitation+”) |

| #6 (MH “Treatment Outcomes+”) OR (MH “Outcome Assessment”) |

| #7 #4 or #5 or #6 |

| #8 #3 and #7 |

| #9 #3 and #7 |

| #10 #3 and #7 |

| #11 #3 and #7 |

| 3 Web of Science |

| #1 Recreation |

| #2 Leisure |

| #3 #1 OR #2 |

| #4 Rehabilitation |

| #5 “Quality of life” |

| #6 Outcome |

| #7 #4 OR #5 OR #6 |

| #8 #3 AND #7 |

| #9 Randomized OR randomised |

| #10 (#8 AND #9) AND Article time span = 1990-2012 |

| 4 Ichushi Web (Originally in Japanese) |

| #1 Recreation/TH or recreation/AL or recreational/AL or recreation/AL or Rikuryeshon/AL or recreation/AL |

| #2 Rehabilitation/HL or rehabilitation/AL or rehabilitation/ALAL |

| #3 #1 and #2 |

| #4 (#3) and (DT = 1990:2012 PT = original papers CK = person) |

| #5 (#4) and (RD = randomized controlled trials, quasi-randomized controlled trials, comparative studies) |

| #6 (#4) and (RD = randomized controlled trials) |

| 5 WPRIM |

| #1 recreation |

| 6 All Cochrane |

| #1 MeSH descriptor Recreation explode all trees |

| #2 (recreation): ti, ab, kw |

| #3 MeSH descriptor Rehabilitation explode all trees |

| #4 MeSH descriptor Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic explode all trees |

| #5 (Randomized controlled trial): ti, ab, kw |

| #6 (#1 OR #2) |

| #7 (#4 OR #5) |

| #8 (#3 AND #6 AND #7), from 1990 to 2012 |

| 7 Campbell Collaboration |

| #1 Recreation |

| 8 ICTRP |

| #1 Recreation |

| 9 Clinical Trials.gov |

| #1 Recreation OR recreational |

| 10 UMIN-CTR (Originally in Japanese) |

| #1 Recreation |

| 11 Japic CTI (Originally in Japanese) |

| #1 Recreation |

| 12 JMACCT CTR (Originally in Japanese) |

| #1 Recreation |

Registry checking: We searched the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), Clinical Trials.gov, the University Hospital Medical Information Network-Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR), the Japan Pharmaceutical Information Center-Clinical Trials Information (Japic CTI), and the Japan Medical Association-Center for Clinical Trials (JMACCT CTR), all up to May 31, 2012. ICTRP and the WHO Registry Network meet specific criteria for content, quality and validity, accessibility, unique identification, technical capacity and administration. Primary registries meet the requirements of the ICMJE. Clinical Trials.gov is a registry of federally and privately supported clinical trials conducted in the United States and around the world. UMIN-CTR, Japic CTI, and JMACCT CTR are registries of clinical trials conducted in Japan and around the world.

Handsearching, reference checking, etc.: We handsearched abstracts published on recreation activities in relevant journals in Japan. We checked the references of included studies for further relevant literature.

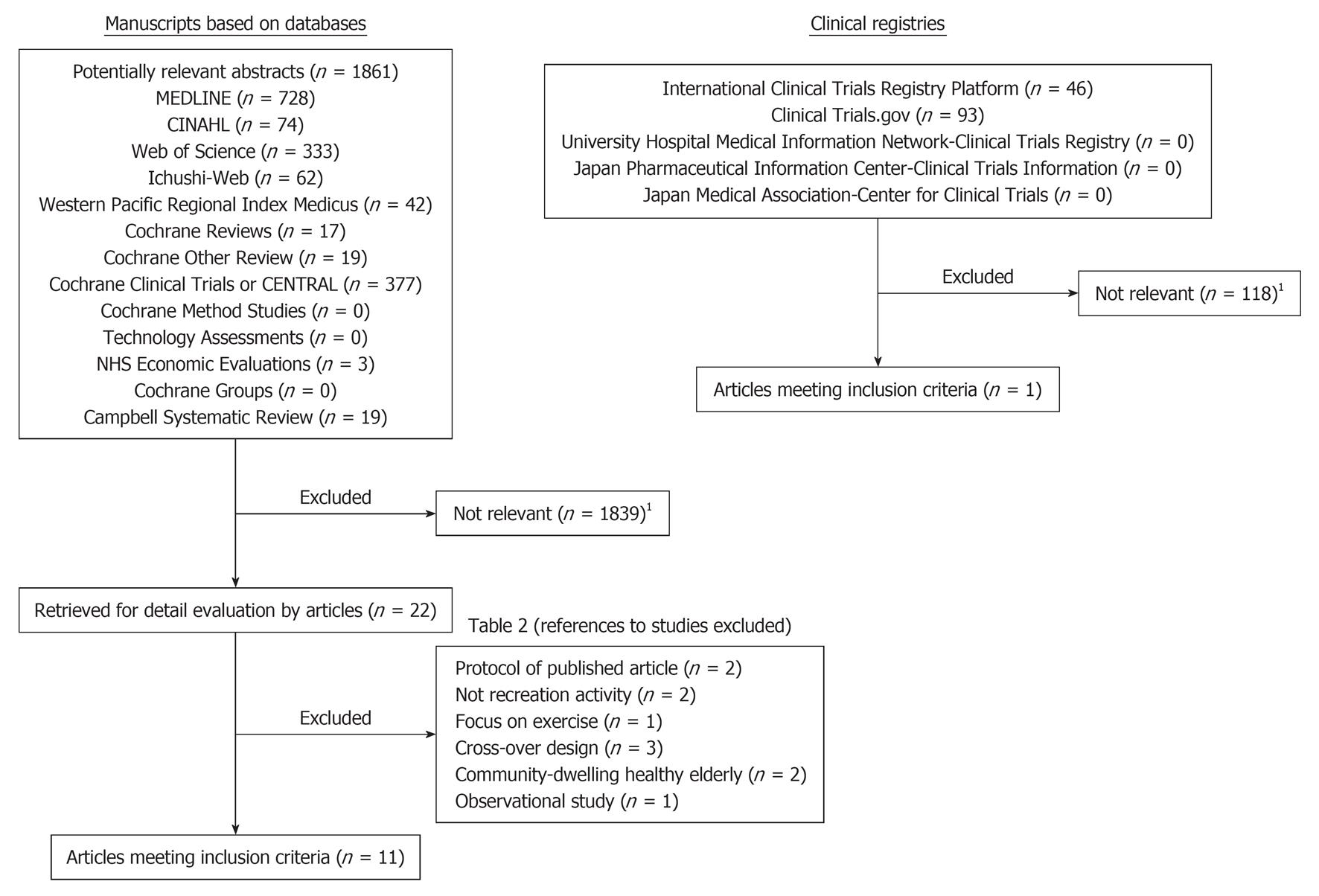

Selection of trials: In order to make the final selection of studies for the review, all criteria were applied independently by five authors (e.g., Honda T, Kitayuguchi J, Okada S, Park SJ) to the full text of articles that had passed the first eligibility screening (Figure 1). Disagreements and uncertainties were resolved by discussion with other authors (e.g., Mutoh Y, Okuizumi H, Park H).

Studies were selected when (1) the design was an RCT; and (2) one of the interventions was a form of recreational activity. Rehabilitation effects were used as a primary outcome measure. Trials that were excluded are presented with reasons for their exclusion (Table 2).

| Excusion No. | Ref. | Title | Reason of exclusion |

| 1 | Green et al[48] | Physiotherapy for patients with mobility problems more than 1 year after stroke: a randomised controlled trial | Not recreation activity |

| 2 | Kobayashi et al[49] | Effects of a fall prevention program on physiacal activities of elderly people living in a rural region: an interventional trial | Community-dwelling healthy elderly |

| 3 | Das et al[50] | The efficacy of playing a virtual reality game in modulating pain for children with acute burn injuries: A randomized controlled trial | Cross-over design |

| 4 | Hurwitz et al[51] | Effects of recreational physical activity and back exercises on low back pain and psychological distress: Findings from the UCLA low back pain study | Observational study |

| 5 | Matsuo[52] | The influence of the exercise using a video game on the physical function and brain activities | Cross-over design |

| 6 | Saposnik et al[53] | Effectiveness of virtual reality exercises in stroke rehabilitation: rationale, design, and protocol of a pilot randomized clinical trial assessing the Wii gaming system | Research protocol |

| 7 | Mitsumura et al[54] | Effect on physical and mental function of a group rhythm exercise for elderly persons certified under the less severe grades of long-term care insurance | Exercise training |

| 8 | Fraga et al[55] | Aerobic resistance, functional autonomy and quality of life of elderly women impacted by a recreation and walking program | Community-dwelling healthy elderly |

| 9 | Watanabe et al[56] | Effects of congnitive rehabilitation with computer training on neurophychological function in schizophrenia | Not recreation activity |

| 10 | Hsu et al[57] | A "Wii" bit of fun: The effects of adding Nintendo Wii Bowling to a standard exercise regimen for residents of long-term care with upper extremity dysfunction | Cross-over design |

| 11 | Kwok et al[58] | Evaluation of the Frails' Fall Efficacy by Comparing Treatments on reducing fall and fear of fall in moderately frail older adults: study protocol for a randomised control trial | Research protocol |

In order to ensure that variation was not caused by systematic errors in the study design or execution, seven review authors (Okuizumi H, Mutoh Y, Okada S, Park SJ, Honda T, Handa S, and Honda T) independently assessed the quality of articles. A full quality appraisal of these papers was made using the combined tool based on the “CONSORT 2010”[20] and the “CONSORT for non-pharmacological trials”[21], developed to assess the methodological quality of non-pharmacological RCTs. These checklists were not originally developed to use as a quality assessment instrument, but we used them because they are the most important tools related to the internal and external validity of trials.

Each item was scored as “present” (p), “absent” (a), “unclear or inadequately described” (), or “not applicable” (n/a). Depending on the study design, some items were not applicable. The “n/a” studies were excluded from calculation for quality assessment. We displayed the percentage of present description in all 47 checked items for the quality assessment of articles. Then, based on the percentage of risk of poor methodology and/or bias, each item was assigned to the following categories: good description (80%-100%), poor description (50%-79%), very poor description (0%-49%). Disagreements and uncertainties were resolved by discussion with other authors (e.g., Okuizumi H, Okada S and Kamioka H). Inter-rater reliability was calculated on a dichotomous scale using percentage agreement and Cohen’s κ coefficient (k).

Summary of studies and data extraction: Seven review authors (Okuizumi H, Mutoh Y, Okada S, Park SJ, Honda T, Handa S and Kamioka H) described the summary from each article based on the recommended structured abstracts[22,23].

The GRADE Working Group[24] reported that the balance between benefit and harm, quality of evidence, applicability, and the certainty of the baseline risk were all considered in judgments about the strength of recommendations. Adverse events, withdrawals, and cost for intervention were especially important information for researchers and users of clinical practice guidelines, and we have presented this information with the description of each article.

Pre-planned stratified analyses were: (1) trials comparing recreational activities with no treatment or waiting list controls; (2) trials comparing different types of general rehabilitation method [e.g., physical therapy, occupational therapy (OT), etc.]; and (3) trials comparing recreational activities with other intervention(s) (e.g., musical appreciation vs singing). We planned to express the results of each RCT, when possible, as relative risk with corresponding 95%CI for dichotomous data, and as standardized or weighted mean differences (SMD) with 95%CI for continuous data. However, heterogeneous results of studies that met inclusion criteria were not combined. All analyses were computed with the “R version 2.15.1”, a free software environment for statistical computing and graphics (URL:http://www.r-project.org/), which compiles and runs on a wide variety of UNIX platforms, Windows.

We submitted and registered our research protocol to the PROSPERO database (No. CRD42012002381)[25]. This is an international database of prospectively registered SRs in health and social care. Key features from the review protocol are recorded and maintained as a permanent record in PROSPERO. This will provide a comprehensive listing of SRs registered at inception, and enable comparison of reported review findings with what was planned in the protocol. PROSPERO is managed by CRD and funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research. Registration was recommended because it encourages full publication of the review’s findings and transparency in changes to methods that could bias findings[26].

The literature searches based on databases included 1861 potentially relevant articles (Figure 1). Abstracts from those articles were assessed and 22 papers were retrieved for further evaluation (checks for relevant literature). Eleven publications were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria (Table 2). Eleven studies[4-6,27-34] met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

The language of all eligible publications was English. Target diseases and/or symptoms (Table 3) were stroke,[6,29,33,34] depression[5], Parkinson’s disease[32], acquired brain injury[28], chronic non-malignant pain (CNMP)[4], adolescent obesity[31], high-risk pregnancy[30], and the frail elderly[27]. Intervention methods were gaming technology[27-29,31,33], music[4,30], dance[32], easy rider wheelchair biking[5], leisure education programs[34], and leisure tasks[6].

| Ref. | Szturm et al[27] | Gil-Gómez et al[28] | Saposnik et al[29] |

| Citation | Phys Ther 2011; 91: 1449-1462 | J Neuroeng Rehabil 2011; 8: 30 | Stroke 2010; 41: 1477-1484 |

| Title | Effects of an interactive computer game exercise regimen on balance impairment in frail community-dwelling older adults: a randomized controlled trial | Effectiveness of a Wii balance board-based system (eBaViR) for balance rehabilitation: a pilot randomized clinical trial in patients with ABI | Effectiveness of virtual reality using Wii gaming technology in stroke rehabilitation: a pilot randomized clinical trial and proof of principle |

| Aim/objective | To examine the feasibility and benefits of physical therapy based on a task-oriented approach delivered via an engaging, interactive video game paradigm. The intervention focused on performing targeted dynamic tasks, which included reactive balance controls and environmental interaction | To evaluate the efficacy of the eBaViR system as a rehabilitation tool for balance recovery in patients with ABI | To examine the feasibility and safety the VR Nintendo Wii gaming system (VRWii) compared with RT in facilitating motor function on the upper extremity required for activities of daily living among patients with subacute stroke receiving standard rehablitation |

| Setting/place | A geriatric day hospital (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) | Hospital NISA Valencia al Mar y Sevilla A ljarafe, Spain | Toronto Rehabilitation Institute |

| Participants | Thirty community-dwelling and ambulatory older adults. Inclusion Criteria; age: 65-85 yr, MMSE score > 24, English-speaking with the ability to understand the nature of the study and provide informed consent, independent in ambulatory functions, with or without an assistive device (cane or walker). without a disability and medical conditions (cancer, kidney disease, fracture, uncontrolled diabetes or seizure disorder, cardiovascular-related problems, stroke, multiple sclerosis, late-stage Parkinson disease, fainting, or dizzy spells) | Twenty participants. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age ≥ 16 yr and < 80 yr; (2) chronicity > 6 mo; (3) absence of cognitive impairment (MMSE > 23); (4) able to follow instructions; and (5) ability to walk 10 m indoors with or without technical orthopaedic aids | Participants (n = 22) who are 18 to 85 yr of age (mean age 61.3 yr) having a first-time ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke |

| Intervention | The control group received the typical rehabilitation program such as strengthening and balance exercise at the day hospital. The experimental group received a program of dynamic balance exercises coupled with computer-based video game play, using a center-of-pressure position signal as the computer mouse. The tasks were performed while standing on a fixed floor surface, with progression to a compliant sponge pad. Each group received 16 sessions, scheduled 2/wk, with 45 min | Each patient participated in a total of 20 1-h-sessions of rehabilitation and accomplished a minimum of 3 sessions and a maximum of 5 sessions per week. During control sessions, traditional rehabilitation exercises that focused on balance training were practiced either individually or in a group. The sessions of the trial group were programmed according to the three games of the system (Simon, Balloon Breaker and Air Hockey) with a system based on the eBaViR. The eBaViR using Nintendo system had a significant improvement in static and/or standing balance (BBS and Anterior Reaches Test) compared to patients who underwent traditional therapy. The patients reported having had fun during the treatment without suffering from cyber side effects, which implies additional motivation and adhesion level to the treatment | Participants received an intensive program consisting of 8 interventional sessions of 60 min each over a 14-d period. Intervention group conducted a virtual reality Wii gaming, and the control group did a RT such as card game |

| Main and secondary outcomes | BBS, TUG, ABC | BBS, Brunel Balance Assessment, and ART | Feasibility and safety were set as the main outcome, and the efficiency was a secondary outcome in this study |

| Randomisation | Group assignment codes were placed in envelopes and sealed. Each individual who agreed to enter the study randomly selected an envelope | The randomization schedule was computer generated using a basic random number generator | The randomization schedule was computer generated using a basic random number generator |

| Blinding/masking | Assessors were blinded to the participant group assignments. The participant names of the GaitRite data files were coded | Program specialsits and assessors were blinded to the patients group assignments | Only caregivers were blinded (single blinding) |

| Numbers randomised | Experimental group (n = 15) and Control group (n = 15) | Trial group (n = 10) and Control group (n = 10) | Virtual Reality Therapy (n = 11) and Recreation Therapy (n = 11) |

| Recruitment | Thirty community-dwelling and ambulatory older adults who were attending the Riverview Health Center Day Hospital for treatment of limitations were recruited to participate in this study | “Seventy-nine hemiparetic patients who had sustained an ABI and were attending a rehabilitation program were potential candidates for participation in this study” | 110 potential candidates were screened to participate in EVREST (the Effectiveness of Virtual Reality Excercises in Stroke Rehabiritation), and a total of 88 patients were excluded |

| Numbers analysed | Experimental group (n = 14) and Control group (n = 13) | Trial group (n = 9) and Control group (n = 8) | Virtual Reality Therapy (n = 10) and Recreation Therapy (n = 10) on the primary end point |

| Outcome | Finding demonstrated significant improvements in posttreatment balance performance scores for both group, and change scores were significantly greater in the experimental group compared with the control group (BBS; P = 0.001, ABC; P = 0.02). No significant treatment effect was observed in either group for the TUG or spatiotemporal gait variables | Patients using eBaViR had a significant improvement in static balance (P = 0.011 in BBS and P = 0.011 in ART) compared to patients who underwent traditional therapy. Regarding dynamic balance, the results showed significant improvement over time in all these measures, but no significant group effect or group-by-time interaction was detected for any of them, which suggest that both groups improved in the same way | Feasibility (time tolerance) and safety (intervention-related adverse event) did not show significant difference between groups. In contrast, the intervention group showed a significant improvement in mean motor function (Wolf Motor Function Test) compared to the control group (-7.4 s; 95%CI: -14.5--0.2) |

| Harm | No description | No adverse events | No adverse events |

| Conclusion | Dynamic balance exercises on fixed and compliant sponge surfaces were feasibly coupled to interactive video game-based exercise. This coupling, in turn, resulted in a greater improvement in dynamic standing balance control compared with the typical exercise program. However, there was no transfer of effect to gait function | The results suggest that eBaViR represents a safe and effective alternative to traditional treatment to improve static balance in the ABI population | Virtual reality Wii gaming technology represents a safe, feasible, and potentially effective alternative to facilitate rehabilitation therapy and promote motor recovery after stroke |

| Trial registration | Clinical Trials.gov (NCT01381237) | No registration | No description |

| Found | Grant from the Riverview Health Centre Foundation, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada: The Fund provided the space at their facility and access to their day hospital program clients for assessment and treatment of the control group | Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia Spain, Projects Consolider-C (SEJ2006-14301/PSIC), “CIBER of Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition, an initiative of ISCIII” and the Excellence Research Program PROMETEO | This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care through the Ontario Stroke System, administered by Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario |

| Cost of intervention | No description | No description | No description |

| Ref. | Bauer et al[30] | Adamo et al[31] | Hackney et al[32] |

| Citation | J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010; 19: 523-531 | Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2010; 35: 805-815 | J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 475-481 |

| Title | Alleviating distress during antepartum hospitalization: a randomized controlled trial of music and recreation therapy | Effects of interactive video game cycling on overweight and obese adolescent health | Effects of dance on movement control in PD: a comparison of Argentine tango and American ballroom |

| Aim/objective | To examine the efficacy of a single session music or recreation therapy intervention to reduce antepartum-related distress among women with high-risk pregnancies extended antepartum hospitalizations | To examine the efficacy of interactive video game stationary cycling (GameBike) in comparison with stationary cycling to music on adherence, energy expenditure measures, submaximal aerobic fitness, body composition, and cardiovascular disease risk markers in overweight and obese adolescents, using a randomized controlled trial design | To compare the effects of tango, waltz/foxtrot and no intervention on functional motor control in individuals with PD |

| Setting/place | Midwestern, suburban teaching hospital with a regional Perinatal Center with 26 private rooms on the antepartum unit | The Endocrinology clinic at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario | No description |

| Participants | Participants (n = 80) were hospitalized with various high-risk obstetric health issues, including preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, preeclampsia, and multiple gestations. They were all over the age of 18 (mean age 31 yr), between 24 and 38 wk of gestation | Thirty obese adolescents between ages of 12-17 yr | Fifty-eight participants with idiopathic PD participated. They were at least 40 yr of age, could stand for at least 30 min, and walk independently for ≥ 3 m with or without an assistive device |

| Intervention | Participants were received a 1-h music or recreation therapy intervention. Music therapists offered a range of interventions for patients, all within the current standards of care of these therapies, included music-facilitated relaxation, active music listening, song writing, music for bonding, and clinical improvisation. Recreation therapy interventions offered included adaptive leisure activities, creative arts, community resource education, and leisure awareness activities | In the experimental group (interactive video game cycling), participants (n = 15) were required to exercise on a GameBike interactive video gaming system that was interfaced with a Sony Play Station 2. Participants were allowed to select from variety of choices, video games to play while cycling and were permitted to switch games during the exercise session. In control group (stationary cycling to music), participants were allowed to listen to music of their choice via radio, CD, or personal music device. The instructions given participants and the general protocol for this condition was the same as for video game condition. The 10-wk program consisted of twice weekly sessions lasting a maximum of 60 min per session, respectively | The both dance classes were taught by the same instructor who was an experienced professional ballroom dance instructor and an American Council on Exercise certified personal trainer. Those in the dance groups attended 1-h classes twice a week, completing 20 lessons in 13 wk. Both genders spent equal time in leading and following dance roles. Healthy young volunteers, recruited from physical therapy, pre-physical therapy and pre-medical programs at Washington University and St. Louis University, served as dance partners for those with PD. Volunteers were educated about posture and gait problems associated with PD |

| Main and secondary outcomes | Antepartum Bedrest Emotional Impact Inventory Scores | Adherence, submaximal aerobic fitness (Peak workload,Time to exhaustion,Peak heart rate), exercise behaviour, body composition, and blood parameters | The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Motor Subscale 3 (UPDRS), BBS, TUG, 6MWT, FOG questionnaire, and forward and backward gait (gait velocity, stride length, and single support time) |

| Randomisation | The groups were assigned by the research coordinator (using a Random Numbers Statistical Table and opaque envelopes containing group membership) to an intervention condition (either a music or recreation therapy) or waitlist control condition | The randomization schedule was computer generated using a basic random number generator | Randomly selecting one of the 3 conditions from a hat |

| Blinding/masking | Only participants were blinded (single blinding) | No blinding | The first author was not blinded to group assignment. The evaluations were videotaped for a rater who was a specially trained physiotherapy student otherwise not involved in the study (blinded assessor). Participants were not informed of the study hypotheses |

| Numbers randomised | Music therapy group (n = 19), recreation therapy group (n = 19), and control group (n = 42) | Video game cycling (n = 15) and Music cycling (n = 15) | Waltz/foxtrot (n = 19), Tango (n = 19), and Control (n = 20) |

| Recruitment | Identified eligible patients through chart review and nursing report during 2003-2005. A total of 136 patients; once enrolled, however, 56 patients were unable to complete the study | Participants were recruited between May 2007 and January 2009 and the final subject assessment was completed in March 2009. A total of 150 families were screened through the Endocrinology clinic at the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario to determine Assessed for eligibility. Thirty families me the all inclusion criteria | Participates were recruited from the St. Louis community through advertisement at local support groups and local community events. Most were directly recruited via telephone from the Washington University Movement Disorders Center database |

| Numbers analysed | Music therapy group (n = 19), recreation therapy group (n = 19), and control group (n = 42) | Video game cycling (n = 13) and Music cycling (n = 13) | Waltz/foxtrot (n = 17), Tango (n = 14), and Control (n = 17) |

| Outcome | Significant association were found between the delivery of music and recreation therapy and reduction of antepartum-related distress in women hospitalized with high-risk pregnancies. These statistically significant reductions in distress persisted over a period of up to 48-72 h (each P < 0.05) | The music group had a higher rate of attendance compared with the video game group (92% vs 86%, P < 0.05). Time spent in minutes per session at vigorous intensity (80%-100% of predicted peak heart rate) (24.9 ± 20 min vs 13.7 ± 12.8 min, P < 0.05) and average distance (km) pedaled per session (12.5 ± 2.8 km vs 10.2 ± 2.2 km, P < 0.05) also favoured the music group. However, both interventions produced significant improvements in submaximal indicators of aerobic fitness as measured by a graded cycle ergometer protocol | Significant improvements were noted in tango and waltz/foxtrot on the BBS, 6MWT and backward stride length when compared with controls (P < 0.05). Control group worsened significantly with respect to disease severity, as measured by the UPDRS, and on time spent in single support during forward and backward walking |

| Harm | No description | No adverse events | No description |

| Conclusion | Single session music and recreation therapy interventions effectively alleviate antepartum-related distress among high-risk women experiencing antepartum hospitalization and should be considered as valuable additions to any comprehensive antepartum program | The results supported the superiority of cycling to music and indicated investing in the more expensive GameBike may not be worth the cost | Tango may target deficits associated with PD more than waltz/foxtrot, but both dances may benefit balance and locomotion |

| Trial registration | No description | Clinical Trials.gov (NCT00983970) | No description |

| Found | No description | The Canadian Diabetes Association | The American Parkinson’s Disease Association and NIH grant K01-048437 |

| Cost of intervention | No description | Participants and their families were reimbursed CAN$10 per visit to the laboratory for parking and transportation costs, and the participants were given a CAN$20 movie theatre gift certificate following trial completion | No description |

| Ref. | Yavuzer et al[33] | Desrosiers et al[34] | Siedliecki et al[4] |

| Citation | Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2008; 44: 237-244 | Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 1095-1100 | J Adv Nurs 2006; 54: 553-562 |

| Title | ‘’Playstation eyetoy games’’ improve upper extremity-related motor functioning in subacute stroke: a randomized controlled clinical trial | Effect of a home leisure education program after stroke: a randomized controlled trial | Effect of music on power, pain, depression and disability |

| Aim/objective | To evaluate the effects of “Playstation EyeToy games” on upper extremity motor recovery and upper extremity-related motor functioning of patients with subacute stroke | To evaluate the effect of a leisure education program on participation in and satisfaction with leisure activities (leisure-related outcomes), and well-being, depressive symptoms, and quality of life (primary outcomes) after stroke | To test the effect of music levels of power, pain, depression, and disability; to compare the effect of researcher-provided relaxing music choices with subject-preferred music, selected daily based on self-assessment; and to test the relationship between power and the combined dependent variable of pain, depression and disability |

| Setting/place | Twenty inpatients with hemiparesis after stroke in rehabilitation center from the general hospital, Turkey | Home and community | Pain clinics and chiropractic office in northeast Ohio, United States |

| Participants | Twenty hemiparetic inpatients with post-stroke. Eligible criteria: (1) first hemiparesis within 12 mo; (2) Brunnstrom stage 1-4 for upper extremity; and (3) no severe cognitive disorders | Sixty-two people (mean age 70 yr) with stroke | Participation of 60 African American and Caucasian people aged 21-65 yr (mean age 49.7 yr) with chronic non-malignant pain CNMP |

| Intervention | Both the intervention group and the control group participated in a conventional stroke rehabilitation program, 5 d a week, 2-5 h/d for 4 wk. The conventional program is patient-specific and consists of neurodevelopmental facilitation techniques, physiotherapy, OT, and speech therapy. For the same 4-wk of period, the EyeToy group received an additional 30 min of VR therapy program | The experimental participants (n = 33) received the leisure education program (leisure awareness, self-awareness, and competence development) at home once a week for 8 to 12 wk. The recreational therapist was responsible for the intervention whereas the occupational therapist acted as a consultant. The control participants (n = 29) were also visited by the recreation therapist but the topics discussed were unrelated to leisure (e.g., family, cooking, politics, news, everyday life) | Patterning Music (PM; subject-preferred music) group were asked to select upbeat, familiar, instrumental or vocal music to ease muscle tension and stiffness. Standard Music (SM; researcher-provided music) group were offered a choice of one 60-min relaxing instrumental music tape from a collection of five tapes (piano, jazz, orchestra, harp and synthesizer) used in several music and acute pain studies. Each group received their assigned intervention for 1-h a day for 7 consecutive days. Control group received standard care that did not include music intervention, and all participants kept a diary for 7 d |

| Main and secondary outcomes | Brunnstrom stages and FIM | Minutes of leisure activity per day, number of leisure activities, the Leisure Satisfaction Scale, the Individualized Leisure Profile, the GWBS, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, and the SA-SIP30 | Power (characterize power: awareness, choices, freedom, and a personal involvement in creating change), pain, depression, and disability |

| Randomisation | The randomization schedule was computer generated using a basic random number generator | The randomization schedule was computer generated using a basic random number generator | The random allocation sequence using the Min-8 program |

| Blinding/masking | Assessor was blinded to the group allocation of the subject. Patients and physical therapist were not blinded | Only assessor was blinded | No description |

| Numbers randomised | Intervention group (n = 10) and Control group (n = 10) | Experimental participants (n = 33) and Control participants (n = 29) | PM group (n = 18), SM group (n = 22), and Control group (n = 20) |

| Recruitment | “Inpatients with hemiparesis after stroke” | A total of 62 people entered the trial carried out in 2002 and 2003. Authors recruited them after a review of medical charts of people (n = 230) who were previously admitted with stroke to a rehabilitation or acute care facility up to 5 yr before the study | 64 patients with CNMP was recruited over a 24-mo period from 2001 to 2003 from pain clinics and a chiropractic office in northeast Ohio |

| Numbers analysed | Intervention group (n = 10) and Control group (n = 10) | Experimental participants (n = 29) and Control participants (n = 27) | PM group (n = 18), SM group (n = 22), and Control group (n = 20), |

| Outcome | The mean change score (95%CI) of the FIM self-care score [(5.5 (2.9-8.0) vs 1.8 (0.1-3.7), P = 0.018] showed significantly more improvement in the EyeToy group compared to the control group. No significant differences were found between the groups for the Brunnstrom stages for hand and upper extremity | There was a statistically significant difference in change scores between the groups for satisfaction with leisure with a mean difference of 11.9 points (95%CI: 4.2-19.5) and participation in active leisure with a mean difference of 14.0 min (95%CI: 3.2-24.9). There was also a statistically significant difference between groups for improvement in depressive symptoms with a mean difference of -7.2 (95%CI: -12.5--1.9). Differences between groups were not statistically significant on the SA-SIP30 (0.2; 95%CI: -1.3-1.8) and GWBS (2.2; 95%CI: -5.6-10.0) | The music groups had more power and less pain (P = 0.002), depression (P = 0.001) and disability (P = 0.024) than the control group, but there were no statistically significant differences between the two music interventions. The model predicting both a direct and indirect effect for music was supported |

| Harm | No adverse events | No description | No description |

| Conclusion | “Playstation EyeToy Games” combined with a conventional stroke rehabilitation program have a potential to enhance upper extremity-related motor functioning in subacute stroke patients | The results indicate the effectiveness of the leisure education program for improving participation in leisure activities, improving satisfaction with leisure and reducing depression in people with stroke | Nurses can help patients with CNMP identify and use music they enjoy as a self-administered complementary intervention to facilitate feelings of power, and to decrease perceptions of pain, depression and disability |

| Trial registration | No description | No description | No description |

| Found | No description | The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-49526) | The Frances Payne Bolton Alumni Association, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland Ohio; Sigma Theta Tau, Delta Omega Research Grant; NRSA (NINR; NIH#1F31nro7565) |

| Cost of intervention | No description | No description | No description |

| Ref. | Fitzsimmons[5] | Parker et al[6] | |

| Citation | J Gerontol Nurs 2001; 27: 14-23 | Clin Rehabil 2001; 15: 42-52 | |

| Title | Easy rider wheelchair biking. A nursing-recreation therapy clinical trial for the treatment of depression | A multicentre randomized controlled trial of leisure therapy and conventional occupational therapy after stroke. TOTAL Study Group. Trial of Occupational Therapy and Leisure | |

| Aim/objective | To determine if participation in a therapy biking program had an effect on the degree of depression in older adults living in a long-term facility in upstate New York | To evaluate the effects of leisure therapy and conventional OT on the mood, leisure participation and independence in ADL of stroke patients 6 and 12 mo after hospital discharge | |

| Setting/place | The New York State Home for Veterans (Veterans’ Home) | Five UK centres: Aintree Fazakerley Hospital, Bristol Southmead Hospital, Edinburgh Western General Hospital, Glasgow Royal Infirmary and Nottingham University Hospital | |

| Participants | Thirty-nine older adults (mean age 80 yr) with depression living a long-term facility | Four hundred and sixty-six stroke patients (mean age 72 yr) | |

| Intervention | Ease rider Program (Therapy program) intervention. The experimental groups received the therapeutic biking program for 1 h a day, 5 d a week, for 2 wk | Two treatment groups (ADL group and Lisure group) received OT interventions at home for up to 6 mo after recruitment. The protocol specified a minimum of 10 sessions lasting not less than 30 min each. The treatment goals set in the ADL group were in term of improving independence in self-care tasks and therefore treatment involved practising these task (such as preparing a meal or walking outdoor). For the leisure group, goals were set in term of leisure activity and so interventions included practising the leisure task as well as any ADL tasks necessary achieve the leisure objective. Control group received no OT treatment within the trial | |

| Main and secondary outcomes | The short-form Geriatric Depression Scale | For mood, the GHQ/For leisure activity, the Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire/For independence in ADL, the Nottingham Extended ADL Scale | |

| Randomisation | No description | The Collaborative Stroke Audit and Research telephone randomization service was used to allocate patients to one of three group: leisure, ADL and control | |

| Blinding/masking | No description | Only participants were blinded | |

| Numbers randomised | Treatment group (n = 20) and Control group (n = 20) | Leisure group (n = 153), ADL group (n = 156), and Control group (n = 157) | |

| Recruitment | The target population (n = 90) was residents with a diagnosis of or symptoms of depression in the New York State Home for Veterans | Recruitment was conducted at five UK centres: Aintree Fazakerley Hospital, Bristol Southmead Hospital, Edinburgh Western General Hospital, Glasgow Royal Infirmary and Nottingham University Hospital. 1750 patients was registered | |

| Numbers analysed | Treatment group (n = 19) and Control group (n = 20) | Leisure group (n = 113), ADL group (n = 106), and Control group (n = 112) | |

| Outcome | The control groups' GDS pretest means of 7.95 increased slightly at the posttest to 8.65, indicating a slight increase (+0.70) in depression. The treatment groups' pretest 7.68 decreased to 4.21 (-3.47) at the posttest, denoting a marked decrease in depression (P < 0.001) | At 6 mo and compared to the control group, those allocated to leisure therapy had nonsignificantly better GHQ scores (-1.2: 95%CI: -2.9-0.5), leisure scores (+0.7: 95%CI: -1.1-2.5) and Extended ADL scores (+0.4: 95%CI: -3.8-4.5): the ADL group had nonsignificantly better GHQ scores (-0.1: 95%CI: -1.8-1.7) and Extended ADL scores (-1.4: 95%CI: -2.9-5.6) and nonsignificantly worse leisure scores (-0.3: 95%CI: -2.1-1.6). The results at 12 mo were similar | |

| Harm | No adverse events | No description | |

| Conclusion | This study contributes to the body of knowledge of nursing regarding options for the treatment of depression in older adults, and is an encouraging that psychosocial interventions may be effective in reducing depression | In contrast to the findings of previous smaller trials, neither of the additional OT treatments showed a clear beneficial effect on mood, leisure activity or independence in ADL measured at 6 or 12 mo | |

| Trial registration | No description | No description | |

| Found | The NewYork State Dementia Research Grant 2000 | NHS Research and Development Programme | |

| Cost of intervention | The cost of a basic bike is approximately $3600 plus shiping | No description |

For gaming technology intervention, Szturm et al[27] reported that dynamic balance exercises on fixed and compliant sponge surfaces could be coupled to interactive video game-based tasks in frail community-dwelling older adults. Gil-Gómez et al[28] reported that virtual treatment with game exercises promotes improvement in the dynamic balance of patients with acquired brain injury. Saposnik et al[29] reported that VR Wii gaming technology represents a safe, feasible, and potentially effective alternative to facilitate rehabilitation therapy and promote motor recovery after stroke. Adamo et al[31] reported that cycling to music was superior to interactive video game cycling in promoting attendance and intensity of exercise expenditure for obese adolescent people, indicating that investment in the more expensive GameBike may not be worth the cost. Yavuzer et al[33] reported that Playstation EyeToy Games combined with a conventional stroke rehabilitation program have the potential to enhance upper extremity-related motor functioning in subacute stroke patients.

Siedliecki et al[4] reported that nurses could help patients with CNMP identify and use music they enjoy as a self-administered complementary intervention to facilitate feelings of power, and to decrease perceptions of pain, depression and disability. Bauer et al[30] reported that single session music and recreational therapy interventions effectively alleviate antepartum-related distress among high-risk women experiencing antepartum hospitalization and should be considered as valuable additions to any comprehensive antepartum program.

Concerning dance intervention, Hackney et al[32] reported that the tango may target deficits associated with Parkinson’s disease more than the waltz/foxtrot, but both dances may benefit balance and locomotion.

Fitzsimmons[5] reported that easy rider wheelchair biking contributed to the body of knowledge regarding options for the treatment of depression in older adults, and provided encouraging findings that psychosocial interventions might be effective in reducing depression.

Desrosiers et al[34] reported that the results for leisure education programs indicated their effectiveness in improving participation in leisure activities, improving satisfaction with leisure and reducing depression in people with stroke.

Parker et al[6] reported that additional OT treatments did not show a clear beneficial effect on mood, leisure activity or independence in ADL measured at 6 or 12 mo.

We evaluated 47 items from the CONSORT 2010 and the “CONSORT for non-pharmacological trials” checklists in more detail (Table 4). Inter-rater reliability metrics for the quality assessment indicated substantial agreement for all 517 items (percentage agreement 97% and k = 0.953).

| Paper Section/Topic | ID | CONSORT 2010; items | Checklist for reporting trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: items | Ref. | Present description1 | |||||||||||

| [27] | [28] | [29] | [30] | [31] | [32] | [33] | [34] | [4] | [5] | [6] | No/sum | Rate (%) | ||||

| Title and abstract | 1a | Identification as a randomised trial in the title | p | p | p | p | a | ? | p | p | a | a | p | 7/11 | 64 | |

| 1b | Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions (for specific guidance see CONSORT for abstracts) | n/a | n/a | p | p | p | p | p | p | ? | ? | p | 7/9 | 78 | ||

| In the abstract, description of the experimental treatment, comparator, care providers, centers, and blinding status | p | p | p | ? | ? | ? | ? | p | ? | ? | ? | 4/11 | 36 | |||

| Introduction | ||||||||||||||||

| Background and objectives | 2a | Scientific background and explanation of rationale | p | p | p | p | p | p | ? | p | p | p | p | 10/11 | 91 | |

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | 11/11 | 100 | ||

| Methods | ||||||||||||||||

| Trial design | 3a | Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial) including allocation ratio | p | ? | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | 10/11 | 91 | |

| 3b | Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility criteria), with reasons | p | p | ? | p | a | ? | p | a | a | a | a | 4/11 | 36 | ||

| Participants | 4a | Eligibility criteria for participants | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | 11/11 | 100 | |

| 4b | Settings and locations where the data were collected | When applicable, eligibility criteria for centers and those performing the interventions | p | ? | p | p | p | ? | p | p | p | p | p | 9/11 | 82 | |

| Interventions | 5 | The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered | Precise details of both the experimental treatment and comparator | p | p | p | p | ? | p | p | ? | p | p | p | 9/11 | 82 |

| Description of the different components of the interventions and, when applicable, descriptions of the procedure for tailoring the interventions to individual participants | a | a | p | p | a | p | a | a | p | p | p | 6/11 | 55 | |||

| Details of how the interventions were standardized | a | a | a | p | a | p | n/a | a | p | ? | p | 4/10 | 40 | |||

| Details of how adherence of care providers with the protocol was assessed or enhanced | a | ? | a | n/a | a | p | n/a | a | ? | ? | ? | 1/9 | 11 | |||

| Outcomes | 6a | Completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | ? | ? | p | 9/11 | 82 | |

| 6b | Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons | p | p | a | n/a | a | n/a | n/a | a | a | a | a | 2/8 | 25 | ||

| Sample size | 7a | how sample size was determined | p | p | a | ? | a | ? | p | a | a | p | p | 5/11 | 45 | |

| 7b | when applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines | p | a | a | n/a | a | n/a | ? | a | a | p | p | 3/9 | 33 | ||

| When applicable, details of whether and how the clustering by care providers or centers was addressed | p | a | a | n/a | a | n/a | ? | a | ? | ? | p | 2/9 | 22 | |||

| Randomisation: | ||||||||||||||||

| Sequence generation | 8a | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence | ? | p | ? | p | p | p | p | p | p | a | p | 8/11 | 73 | |

| 8b | Type of randomisation; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size) | n/a | n/a | p | n/a | ? | n/a | p | ? | a | a | a | 2/7 | 29 | ||

| When applicable, how care providers were allocated to each trial group | n/a | n/a | a | n/a | ? | n/a | a | ? | p | ? | p | 2/7 | 29 | |||

| Allocation concealment mechanism | 9 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned | a | a | p | p | ? | p | p | ? | p | a | p | 6/11 | 55 | |

| Implementation | 10 | Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions | a | a | p | p | ? | p | p | ? | a | a | p | 5/11 | 45 | |

| Details of the experimental treatment and comparator as they were implemented | a | a | p | p | ? | p | p | ? | p | ? | p | 6/11 | 55 | |||

| Blinding | 11a | If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how | p | p | p | p | a | p | p | p | a | a | a | 7/11 | 64 | |

| Whether or not those administering co-interventions were blinded to group assignment | ? | ? | a | ? | a | ? | a | ? | a | a | a | 0/11 | 0 | |||

| 11b | if relevant, description of the similarity of interventions | If blinded, method of blinding and description of the similarity of interventionist | ? | ? | a | p | a | p | a | a | a | a | a | 2/11 | 18 | |

| Statistical methods | 12a | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes | ? | ? | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | 9/11 | 82 | |

| 12b | Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses | a | a | n/a | n/a | a | n/a | p | a | p | a | p | 3/8 | 38 | ||

| when applicable, details of whether and how the clustering by care providers or centers was addressed | a | a | n/a | n/a | a | n/a | a | a | p | p | p | 3/8 | 38 | |||

| Results | ||||||||||||||||

| Participant flow (a diagram is strongly recommended) | 13a | For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analysed for the primary outcome | The number of care providers or centers performing the intervention in each group and the number of patients treated by each care provider or in each center | a | a | p | p | p | ? | p | p | p | p | p | 8/11 | 73 |

| 13b | For each group, losses and exclusions after randomisation, together with reasons | ? | ? | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | 9/11 | 82 | ||

| Recruitment | 14a | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up | ? | ? | p | ? | p | ? | p | p | p | p | p | 7/11 | 64 | |

| 14b | Why the trial ended or was stopped | ? | ? | p | n/a | p | n/a | p | p | p | a | p | 6/9 | 67 | ||

| Baseline data | 15 | A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | When applicable, a description of care providers (case volume, qualification, expertise, etc.) and centers (volume) in each group | p | p | p | p | a | p | p | a | a | a | p | 7/11 | 64 |

| Numbers analysed | 16 | For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | 11/11 | 100 | |

| Outcomes and estimation | 17a | For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval) | p | p | p | p | a | p | p | p | p | p | p | 10/11 | 91 | |

| 17b | For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended | ? | ? | p | n/a | a | n/a | a | a | a | a | a | 1/9 | 11 | ||

| Ancillary analyses | 18 | Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing prespecified from exploratory | a | a | n/a | n/a | a | n/a | n/a | a | p | a | a | 1/7 | 14 | |

| Harms | 19 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group (for specific guidance see CONSORT for harms) | a | p | a | ? | p | ? | p | a | a | a | a | 3/11 | 27 | |

| Discussion | ||||||||||||||||

| Limitations | 20 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses | p | p | p | p | a | p | p | p | p | p | a | 9/11 | 82 | |

| Generalisability | 21 | Generalisability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings | In addition, take into account the choice of the comparator, lack of or partial blinding, and unequal expertise of care provides or centers in each group | p | p | p | p | ? | p | ? | ? | p | a | a | 6/11 | 55 |

| Interpretation | 22 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | p | p | p | p | ? | p | p | ? | p | ? | p | 8/11 | 73 | |

| Generalizability (external validity) of the trial findings according to the intervention, comparators, patients, and care providers and centers involved in the trial | ? | ? | p | p | ? | ? | ? | ? | p | ? | ? | 3/11 | 27 | |||

| Other information | ||||||||||||||||

| Registration | 23 | Registration number and name of trial registry | p | a | ? | ? | p | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 2/11 | 18 | |

| Protocol | 24 | Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available | p | a | p | ? | a | ? | a | a | a | a | a | 2/11 | 18 | |

| Funding | 25 | Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders | p | ? | p | ? | a | p | p | p | p | p | p | 8/11 | 73 | |

This assessment evaluated the quality of how the main findings of the study were summarized in the written report. There was a remarkable lack of description in the studies of the methods, results, discussion, and other information in general. The items for which the description was lacking (very poor; < 50%) in many studies were as follows (present ratio; %): “in the abstract, description of the experimental treatment, comparator, care providers, centers, and blinding status” (36%); “important changes to methods after trial commencement” (36%); “details of how the interventions were standardized” (40%); “details of how adherence of care providers with the protocol was assessed or enhanced” (11%); “any changes to trial outcomes after the trial outcomes after the trial commenced” (25%); “how sample size was determined” (45%); “when applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines” (22%); “when applicable, details of whether and how the clustering by care providers or centers was addressed” (11%); “type of randomization” (29%); “when applicable, how care providers were allocated to each trial group” (29%); “who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to intervention” (45%); “whether or not those administering co-interventions were blinded to group assignment” (0%); “if blinded, method of blinding and description of the similarity of interventionist” (18%); “methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses” (38%); “when applicable, details of whether and how the clustering by care providers or centers was addressed” (38%); “for binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended” (11%); “results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing pre-specified from exploratory” (14%); “all important harmful or unintended effects in each group” (27%); “generalizability (external validity) of the trial findings according to the intervention, comparators, patients, and care providers and centers involved in the trial” (27%); “registration number and name of trial registry” (18%); and “where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available” (18%).

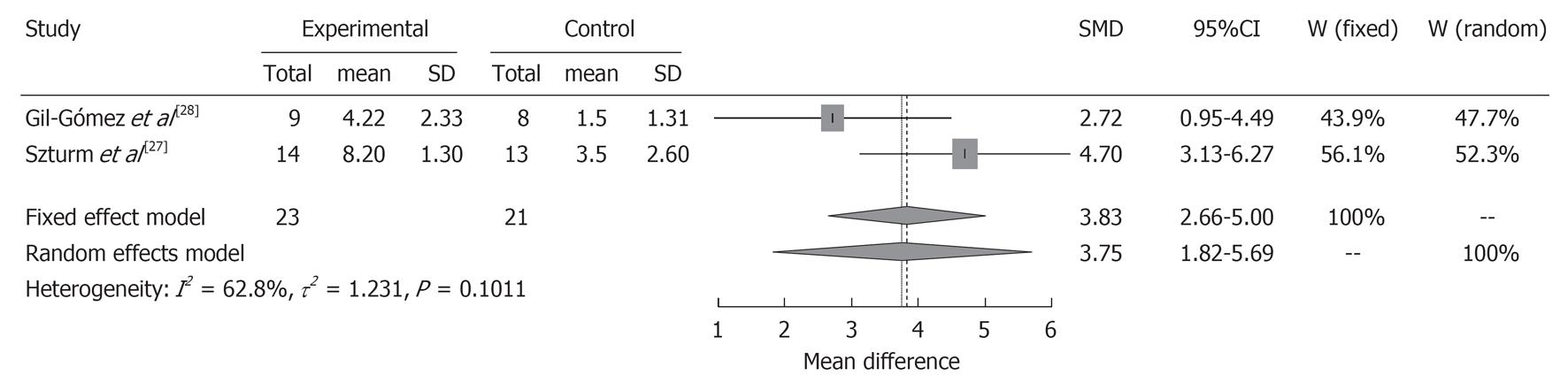

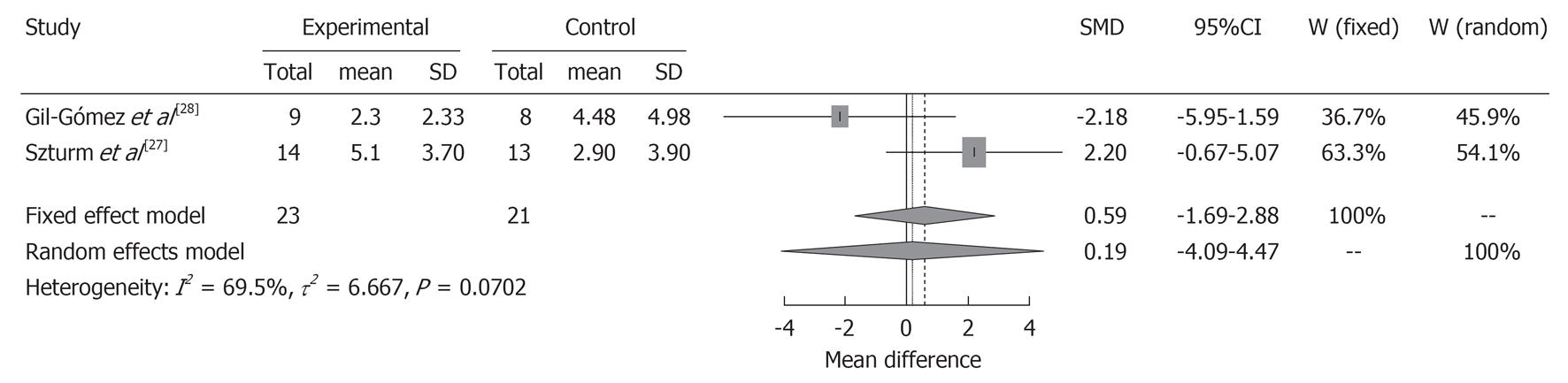

Results from RCTs with control groups[27,28] were pooled in a meta-analysis to establish the overall effect of balance ability interventions compared with no-interventions controls (Figures 2 and 3). For the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), the included interventions were sufficiently homogenous (I2 = 62.8%, P = 0.101), so the fixed effects model was used. This revealed a non-significant difference in balance ability favoring interventions over controls at the last reported assessment (SMD = 3.75; 95%CI: 1.82-5.69; n = 44). For the Timed “Up and Go” (TUG), the interventions were homogenous (I2 = 69.5%, P = 0.070), so the fixed effects model was also used. This revealed a no significant difference in balance ability favoring interventions over controls (SMD = 0.19; 95%CI: -4.09-4.47; n = 44). A funnel plot to assess publication bias was not generated as fewer than 10 interventions were included in the meta-analysis[35].

Five studies[5,28,29,31,33] reported no adverse events during all interventions but there were no descriptions of adverse events in the other studies (Table 3). Two studies[29,32] reported no withdrawals (dropouts), nine studies showed some dropouts because of mainly death, death in family, hospitalization, and injuries due to other causes. The reasons preventing patients from recreational activities were not shown.

Two studies[5,31] described the costs of intervention (Table 3). Adamo et al[31] showed parking and transportation costs, as well as movie theatre gift certificates following the trial completion. Fitzsimmons[5] showed the cost of an easy rider wheelchair bike. There was no information regarding costs of intervention in the other studies.

This is the first SR of the effectiveness of rehabilitation based on recreational activities. Eleven RCTs were identified, target diseases and/or symptoms included stroke, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, acquired brain injury, CNMP, adolescent obesity, high-risk pregnancy, and the frail elderly. The intervention methods included various approaches such as gaming technology, music, dance, easy rider wheelchair biking, leisure education programs, and leisure tasks. Primary or secondary outcomes were generally psychological status (depression, mood, emotion, and power), balance or motor function, and adherence (feasibility and attendance).

The trend over the past 10 years towards game interventions by VR is particularly interesting. Basically, sedentary screen time has been shown to be associated with obesity[36] as well as negative health outcomes such as premature death[37,38], independent of physical activity levels[39]. However, one strategy, the term “active video gaming” or “virtual gaming” has been used to describe games in which body movement is necessary or encouraged by the control scheme of each game. Typically, active games use a motion-sensing or motion-encouraging controller rather than a traditional handheld game pad controller. Lyons et al[40] reported that dance simulation and fitness games seemed to have the potential to produce moderate-intensity physical activity in physiological experiments. A recent SR[41] without meta-analysis, based on video games reported that there is potential for video games to improve health-related outcomes, particularly in the area of psychological and physical therapy. However, the included RCTs were of relatively low quality. A discussion, including a meta-analysis to clearly demonstrate an effect of the video game, was required.

For BBS and TUG as an indicator of balance ability, the interventions were not identical, but the results for both revealed no significant differences in balance ability between interventions and controls. One reason for this was that the pooled sample size was very small (two studies, 44 participants) and we could not, therefore, calculate and describe a funnel plot to assess publication bias. It may be difficult to recruit many patients as participants in rehabilitation studies, although studies (cluster- or multicenter-RCTs depending on the case) with sufficient numbers of subjects are necessary. The second problem may be that the dose-regimen, such as period and frequency of the interventions, was inadequate. The mental and physical burden on participants is increased when there is substantial intervention, although it is expected that the effect of balance ability would rise in a positive relationship with the quantity of intervention. Because a gradual increase in load with recovery is necessary in rehabilitation programs, it is easy to assign settings like “Level” or “Stage” for the game, such as first, second level, etc. Therefore, we also expect to understand correctly the results and detailed descriptions of “pragmatic trials”[42] as well as “explanatory trials” for the rehabilitation effects of game intervention.

In all other interventions, there wa at least one effect on psychological status, balance or motor function, and adherence as the primary or secondary outcomes. However, it was impossible to perform a meta-analysis and integrate the results since the main outcome measures and interventions were different. Therefore, we recognize the potential for recreational activities to improve rehabilitation effects, but could not provide conclusive evidence of these rehabilitation effects.

The CONSORT 2010 and the CONSORT for non-pharmacological trials checklists were not originally developed for use as quality assessment instruments, but we used them as such because they are the most important tools related to the internal and external validity of trials. There were serious problems with the conduct and reporting of the target studies. In particular, our review detected omissions in the following descriptions: methods used to generate the random allocation sequence, blinding, care provider, estimated effect size and its precision, harm, external validity, and trial registry with protocol. Descriptions of these items were lacking (very poor; < 50%) in many studies.

In the Cochrane Review, the eligibility criteria for a meta-analysis are strict, and for each article, heterogeneity and low quality of reporting must first be excluded. Because there was insufficient evidence in the studies of recreational intervention, due to poor methodological and reporting quality as well as heterogeneity, we are unable to offer any conclusions about the effects of rehabilitation by recreational intervention based on RCTs. Both the CONSORT 2010 and the CONSORT for non-pharmacological trials checklists are relatively new, but it was shown that the study protocol description and implementation for recreational studies could be subjected to these checklists.

The results of this study suggest that few RCTs have been conducted in this area, and that the RCTs conducted have been of relatively low quality. Table 5 shows the future research agenda for studies of the rehabilitation effect by recreational activity. There is potential for effects on psychological status, balance or motor function, and adherence, but the overall evidence remains unclear. Therefore, researchers should use the appropriate checklists for research design and intervention method, as this would lead to improvement in the quality of the study, and would contribute to the accumulation of evidence. Researchers should also present not only the efficacy data, but also description of any adverse events or harmful phenomena and withdrawals. Many studies in this review did not describe these factors.

| Overall evidence in the present | Research agenda |

| Structural description of papers based on the CONSORT 2010 and the CONSORT for nonpharmacological trials | |

| 1 Satisfactory description and methodology | |

| There is potential for effects such as psychological status, balance or motor function, and adherence but overall evidence remains unclear | (Method used to generate the random allocation sequence, blinding, care provider, estimated effect size and its precision, harm, external validity, and trial registry with protocol) |

| 2 Description of intervention dose (if pragmatic intervention) | |

| 3 Adequate sample size to perform a meta-analysis | |

| 4 Description of adverse effects (e.g., dizziness by watching screen) | |

| 5 Description of withdrawals | |

| 6 Description of cost (e.g., gaming equipment) | |

| 7 Development of the original check item in recreation activity |

A recent study[43] suggested that public health is moving toward the goal of implementing evidence based intervention. However, the feasibility of possible interventions and whether comprehensive and multilevel evaluations are needed to justify them must be determined. It is at least necessary to show the cost of such interventions. We must choose to introduce an interventional method based on its cost-benefit, cost-effectiveness, and cost-utility. In addition, recreational activities as intervention are unique and completely different than pharmacological or traditional rehabilitation methods. Therefore it may be necessary to add some original items such as herbal intervention[44], aquatic exercise[45], and balneotherapy[46] to the CONSORT checklist as alternative or complementary medicines.

This review had several strengths: (1) the methods and implementation registered high on the PROSPERO database; (2) it was a comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases with no data restrictions; (3) there were high agreement levels for quality assessment of articles; and (4) it involved detailed data extraction to allow for collecting all of an article’s content into a recommended structured abstract. The conduct and reporting of this review also aligned with the PRISMA statement[47] for transparent reporting of SRs and meta-analyses.

This review also had several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, although some selection criteria were common across studies, as described above, bias remained due to differences in eligibility for participation in each study. Secondly, publication bias was a limitation. Although there was no linguistic restriction in the eligibility criteria, we searched studies with only English and Japanese key words. In addition, this review reported on a relatively small and heterogeneous sample of studies. Moreover we could not follow standard procedures for estimating the effects of moderating variables. Finally, although we used an original definition of recreation activity because of the lack of a clear worldwide definition, our definition was not universal.

In conclusion, this comprehensive SR demonstrates that recreational activities may have the potential for improving rehabilitation in a wide variety of areas, and for a variety of patients and elderly people. To most effectively assess the potential benefits of recreational activities for rehabilitation, it will be important for further research to utilize (1) RCT methodology (person unit or cluster unit) when appropriate; (2) an intervention dose; (3) a description of adverse effects and withdrawals; and (4) the cost of recreation activities.

We would like to express our appreciation to Ms. Rie Higashino and Ms. Yoko Ikezaki (paperwork), Ms. Satoko Sayama and Ms. Mari Makishi (all searches of studies) for their assistance in this study.

Recreational activity is anything that is stimulating and rejuvenating for an individual. “Enjoyment” is an important factor that may aid adherence to training for rehabilitation.

Although many studies have reported the rehabilitation effects of recreational activities, there is no systematic review (SR) of the evidence based on randomized controlled trials.

This is the first SR of the effectiveness of rehabilitation based on recreational activities. There were serious problems with the conduct and reporting of the target studies. In particular, this review detected omissions in the following descriptions: methods used to generate the random allocation sequence, blinding, care provider, estimated effect size and its precision, harm, external validity, and trial registry with protocol. Descriptions of these items were lacking (very poor; < 50%) in many studies.

There is a potential for recreational activities to improve rehabilitation-related outcomes, particularly in psychological status (depression, mood, emotion, and power), balance or motor function, and adherence (feasibility and attendance).

For rehabilitation, the World Health Organization explains that rehabilitation of people with disabilities is a process aimed at enabling them to reach and maintain their optimal physical, sensory, intellectual, psychological and social functional levels. The definition of the recreational activity is complex but, in this study, it distinguishes the specific exercise item. Specifically, any kind of recreation activity (not only dynamic activities but also musical appreciation or play, painting, hand-craft, etc.) was permitted and defined as an intervention.

The authors have done an excellent job in presenting results, with a format different than that normally employed in works of meta-analysis. This did not include the usual estimates of effect size based on meta-analytical indicators but is likely that this did not lead to major complications, given the number of studies analyzed. It is a good descriptive work, very systematic and ordered.

P- Reviewer Guardia-Olmos J S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Pan W. Examples of Recreational Activities - Fun Things to Do. Available from: http://ezinearticles.com/Examples-of-Recreational-Activities---Fun-Things-to-Do&id=1566968. Accessed July 29, 2012. |

| 2. | Veal AJ. Research methods for leisure and tourism: a practical guide. London: Pearson Education 2006; . |