Published online May 26, 2013. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v1.i1.10

Revised: March 20, 2013

Accepted: April 9, 2013

Published online: May 26, 2013

Processing time: 93 Days and 23.6 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the benefits of low-volume polyethylene glycol (PEG) with ascorbic acid compared to full-dose PEG for colonoscopy preparation.

METHODS: MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, PubMed, and recent abstracts from major conferences were searched (January 2012). Only randomized-controlled trials on adult subjects comparing low-volume PEG (2 L) with ascorbic acid vs full-dose PEG (3 or 4 L) were included. Meta-analysis for the efficacy of low-volume PEG with ascorbic acid and full-dose PEG were analyzed by calculating pooled estimates of number of satisfactory bowel preparations as well as adverse patient events (abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting). Separate analyses were performed for each main outcome by using OR with fixed and random effects models. Heterogeneity was assessed by calculating the I2 measure of inconsistency. RevMan 5.1 was utilized for statistical analysis.

RESULTS: The initial search identified 242 articles and trials. Nine studies (n = 2911) met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed for this meta-analysis with mean age range from 53.0 to 59.6 years. All studies were randomized controlled trials on adult patients comparing large-volume PEG solutions (3 or 4 L) with low-volume PEG solutions and ascorbic acid. No statistically significant difference was noted between low-volume PEG with ascorbic acid and full-dose PEG for number of satisfactory bowel preparations (OR 1.07, 95%CI: 0.86-1.33, P = 0.56). No statistically significant difference was noted between low-volume PEG with ascorbic acid and full-dose PEG for abdominal pain (OR 1.09, 95%CI: 0.81-1.48, P = 0.56), nausea (OR 0.70, 95%CI: 0.49-1.00, P = 0.05), or vomiting (OR 0.99, 95%CI: 0.78-1.26, P = 0.95). No publication bias was noted.

CONCLUSION: Low-volume PEG with the addition of ascorbic acid demonstrates no statistically significant difference to full-dose PEG for satisfactory bowel preparation and side-effects.

Core tip: Optimal visualization of the colon during colonoscopy requires adequate bowel preparation that is effective and tolerable to the patient. Low-volume polyethylene glycol (PEG) preparation coupled with ascorbic acid has been utilized to enhance patient tolerability without affecting the quality of bowel preparation. This meta-analysis shows that bowel preparation with low-volume PEG with ascorbic acid does not differ from full-dose PEG for quality of bowel preparation or patient tolerability.

- Citation: Godfrey JD, Clark RE, Choudhary A, Ashraf I, Matteson ML, Puli SR, Bechtold ML. Ascorbic acid and low-volume polyethylene glycol for bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy: A meta-analysis. World J Meta-Anal 2013; 1(1): 10-15

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v1/i1/10.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v1.i1.10

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third-leading cause of cancer and second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States[1]. In 2012, it is estimated that 143460 new cases of CRC will be diagnosed and 51690 deaths will occur secondary to this disease[1]. Given these estimations, it has become increasingly important to screen for and prevent CRC, ideally detecting the disease in an early stage. Colonoscopy has become a widely available screening test for both preventing and detecting CRC and has been recommended as the preferred CRC prevention test by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG)[2]. Furthermore, colonoscopy is an important tool in the work-up and management of various other conditions including inflammatory bowel disease, lower-gastrointestinal bleeding, and diarrhea[3-6].

To provide optimal visualization of the colonic mucosa during exam, colonoscopy is dependent on an adequate bowel preparation[7,8]. In order to accomplish this, patients are asked to drink, at times, large volumes of colon preparation solutions[9-11]. This large amount of oral intake prior to a colonoscopy can lead to patient discomfort, nausea, vomiting, and poor patient compliance, which, in turn, leads to a poor colon preparation and increased potential for missed lesions and need for repeat colonoscopy[12-14].

Several bowel cleansing preparations have been developed and used over the years. One of the most common preparations is polyethylene glycol (PEG) which was introduced in 1980[15]. The use of PEG generally requires the ingestion of a large volume of solution (usually 4 L). Several studies have investigated the utility of a low-volume PEG solution (2-3 L) with the addition of adjunct therapy such as a laxative or additive[16-18]. More specifically, some studies have compared a standard PEG preparation to a low-volume PEG preparation coupled with ascorbic acid, acting as an osmotic laxative[19-27]. The low-volume of PEG solution used in these studies has been theorized to decrease patient side-effects and improve patient compliance, resulting in a higher quality of bowel preparation. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to compare low-volume PEG solution with ascorbic acid to standard volume PEG solution for bowel preparation for colonoscopy.

All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on adult patients comparing large-volume PEG solutions (3 or 4 L) with low-volume PEG solutions and ascorbic acid were included in our analysis.

A three-stage search method was utilized to maximize search results. First, a comprehensive search was performed in MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, PubMed in January 2012. Second, references of the retrieved articles and reviews were manually searched for any additional articles. Third, a manual search of abstracts submitted to the Digestive Disease Week and the ACG national meetings was performed from 2003-2011. All articles were searched irrespective of language, publication status (articles or abstracts), or results. The search terms used were PEG and ascorbic acid. Only randomized-controlled trials on adult subjects that compared low-volume PEG (2 L) with ascorbic acid vs full-dose PEG (3 or 4 L) were included. Standard forms were used to extract data by two independent reviewers. Each study was evaluated by a Jadad score[28] and criteria based on Jüni et al[29] to assess the quality of the study.

A meta-analysis was performed comparing the efficacy of low-volume PEG with ascorbic acid and full-dose PEG by calculating pooled estimates of number of satisfactory bowel preparations as well as adverse patient events including abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Separate analyses were performed for each main outcome by using OR with fixed and random effects models which was considered significant if P < 0.05 and 95%CI does not include 1. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed by calculating I² measure of inconsistency which was considered significant if P < 0.10 or I2 > 50%. If heterogeneity was statistically significant, a study elimination analysis was utilized to examine for heterogeneity when certain studies were excluded from the analysis. RevMan 5.1 was utilized for statistical analysis. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plots.

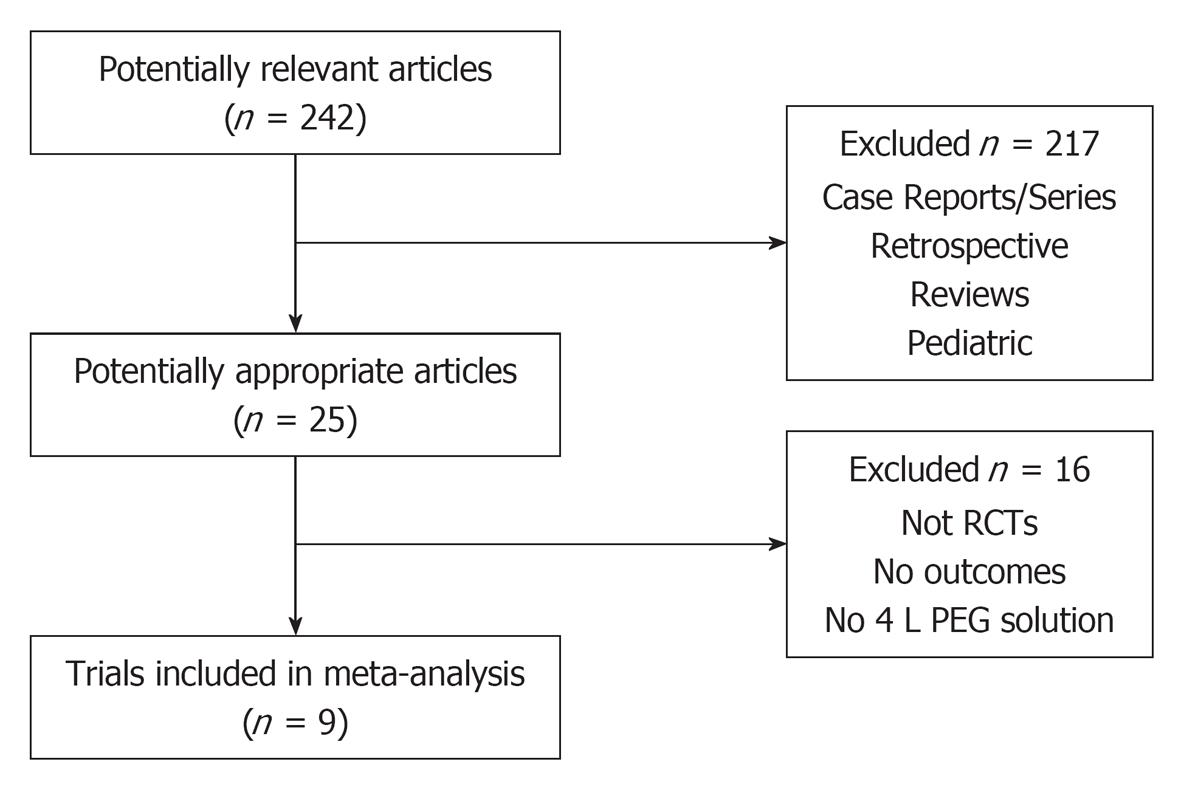

The initial search identified 242 articles and trials (Figure 1). Nine studies satisfied the inclusion criteria (n = 2911) with a mean age range from 53.0 to 59.6 years. Table 1 shows a summary of the details for each study including the low-volume and full-dose preparations. All studies used 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid vs 3 or 4 L PEG solutions.

| Author | Type of study | Blinding | Location | No. of patients | Low-volume bowel preparation | Full-dose bowel preparation | Jadad Score |

| Clark et al[27] 2007 | RCT Abstract | Single | Not specified | 294 | 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid | 4 L PEG | 1 |

| Ell et al[24] 2008 | RCT | Single | Germany | 308 | 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid | 4 L PEG | 3 |

| Lee et al[26] 2008 | RCT Abstract | Single | Not specified | 56 | 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid | 4 L PEG | 1 |

| Corporaal et al[22] 2010 | RCT | Single | Netherlands | 307 | 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid | 4 L PEG | 2 |

| Marmo et al[23] 2010 | RCT | Single | Italy | 433 | 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid | 4 L PEG | 3 |

| Pontone et al[19] 2011 | RCT | Single | Italy | 130 | 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid | 4 L PEG with Simethicone | 3 |

| Jansen et al[21] 2011 | RCT | Single | Netherlands | 370 | 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid +/- Simethicone | 4 L PEG +/- Simethicone | 3 |

| González-Méndez et al[25] 2011 | RCT Abstract | Single | Spain | 681 | 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid + Bisacodyl | 3 L PEG + Bisacodyl | 1 |

| Valiante et al[20] 2012 | RCT | Single | Italy | 332 | 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid | 4 L PEG | 3 |

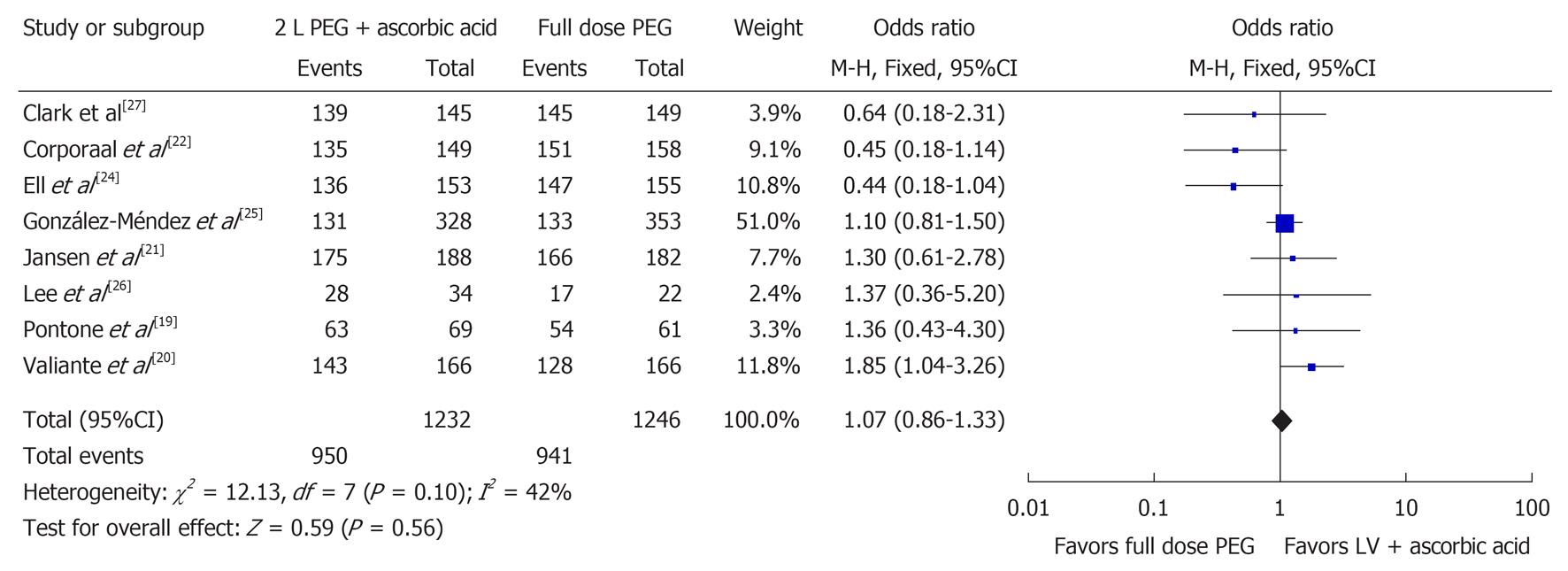

Eight studies examined the number of satisfactory bowel preparations (n = 2478)[19-22,24-27]. Among these 2478 patients, it was found that 1891 had a satisfactory bowel preparation with 950 in the 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid group and 941 in the full-dose PEG group. No statistically significant difference between the two groups was found when evaluating for satisfactory bowel preparation (OR 1.07, 95%CI: 0.86-1.33, P = 0.56). Figure 2 shows the Forest plot for satisfactory bowel preparations. No statistically significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 42%, P = 0.10).

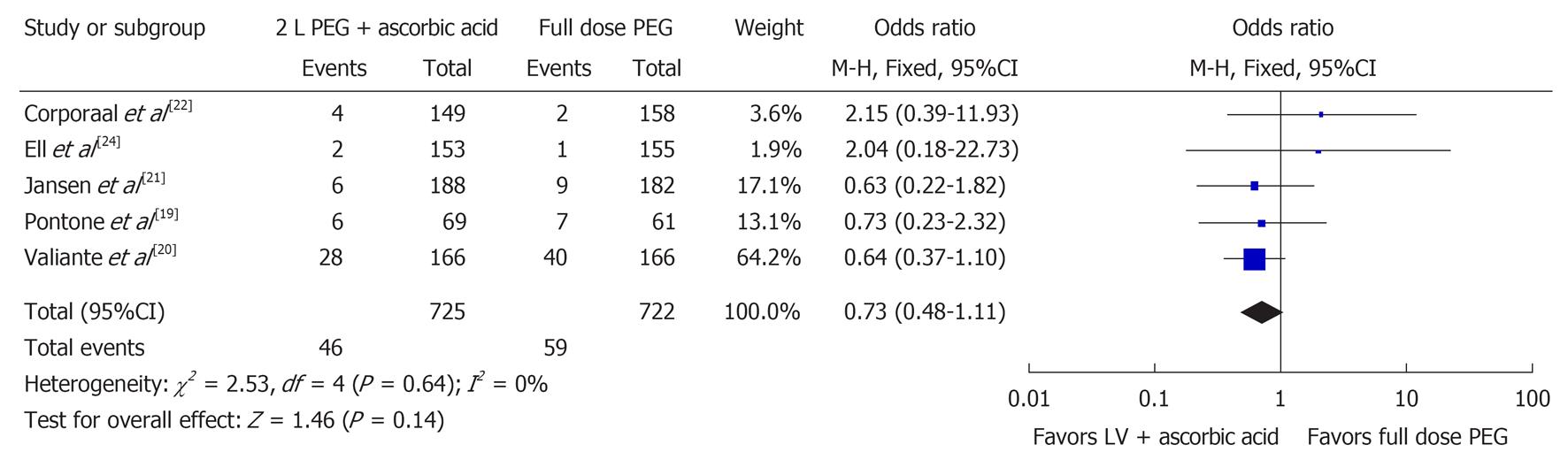

Five studies examined the number of poor bowel preparations (n = 1447)[19-22,24]. Figure 3 shows the Forest plot for these results. There was no significant difference for poor bowel preparation (OR 0.73, 95%CI: 0.48-1.11, P = 0.14) between the two groups. No significant heterogeneity was noted in the poor bowel preparation group (I2 = 0%, P = 0.64).

Gastrointestinal side effects including abdominal pain[19-24] (n = 1880), nausea[19,20,22-24] (n = 1510), and vomiting[19,20,22-25] (n = 2191) were analyzed. No statistically significant difference was found for abdominal pain (OR 1.09, 95%CI: 0.81-1.48, P = 0.56) or vomiting (OR 0.99, 95%CI: 0.78-1.26, P = 0.95) (Table 2). A trend was noted for less nausea in the 2 L with ascorbic acid as compared to full-dose PEG; however, no statistical significance was reached (OR 0.70, 95%CI: 0.49-1.00, P = 0.05).

| Side effect | OR | 95%CI | P-value | Significance |

| Abdominal pain | 1.09 | 0.81-1.48 | 0.56 | NS |

| Nausea | 0.70 | 0.49-1.00 | 0.05 | NS |

| Vomiting | 0.99 | 0.78-1.26 | 0.95 | NS |

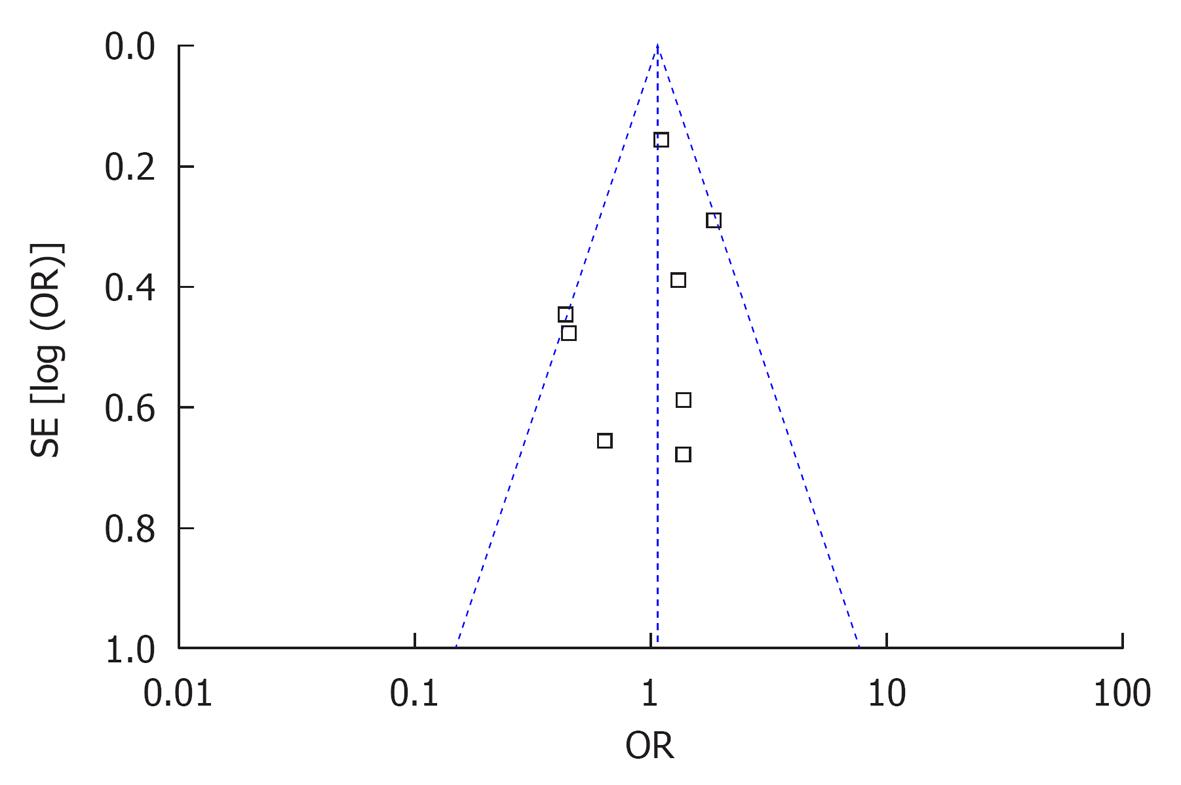

No statistically significant publication bias was noted (Figure 4).

Colonoscopy is a widely available and highly useful diagnostic tool for evaluating colonic and terminal ileal disease. Its success largely depends on an adequate bowel preparation to allow a thorough examination of the colonic and ileal mucosa. Various bowel preparations have been developed over the years under the premise that an ideal bowel preparation is one that is palatable to the patient, effective in cleansing quality, relatively small in volume, and tolerated well by patients with minimal adverse gastrointestinal symptoms.

One of the most commonly used bowel preparations has been 4 L of PEG solution. While effective, it requires the patient to consume a large amount of volume over a short period of time, resulting in some that are unable to tolerate the preparation. Due to this large volume, several recent studies, including a meta-analysis, have evaluated the effectiveness of administering the PEG solution in a split-dose with half given the evening before and half given the morning of the procedure[30]. While this study showed an improvement in bowel cleansing and decrease in some gastrointestinal side effects, patients still need to consume 4 L of PEG solution. Other studies have used lower-volume 2 L PEG solutions with various adjuncts including senna, bisacodyl, or magnesium citrate. These studies showed an improvement in tolerability but suggested a decrease in efficacy[16-18]. More recently, several studies have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness and tolerability of a low-volume 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid as compared to full-dose 4 L PEG. These studies suggested that the reduced volume solution is effective in bowel cleansing but may not offer any advantages in reducing potential gastrointestinal side-effects.

Our meta-analysis was conducted to clarify the overall effects of a low-volume 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid compared to full-dose 4 L PEG solution. Only RCTs in adult patients were evaluated and used in this study. Based on our findings, low-volume PEG with ascorbic acid was equally effective in producing a satisfactory bowel preparation during colonoscopy, suggesting this to be a reasonable alternative to full-dose 4 L PEG solution with comparable bowel cleansing properties. However, patients receiving the low-volume 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid showed a similar pattern in gastrointestinal side effects including abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting when compared to full-dose 4 L PEG solution, offering no overt advantage. One possible explanation for this is that patients receiving the 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid are required to consume an additional 500 mL of clear liquids after each 1 L of solution, totaling 3 L of liquid volume consumed during this preparation. One could argue that this still requires patients to ingest a moderate-to-large amount of fluid during a short period of time.

The strengths of our meta-analysis include the use of RCTs in various populations and end-points that are significant to clinical practice. This also represents the first meta-analysis performed on this subject. However, a few limitations to this meta-analysis do exist. First, uniformity between the studies in using only 2 L PEG with ascorbic acid and full-dose PEG solution was not consistent among all studies. González-Méndez et al[25] used a 3 L PEG solution rather than the typical 4 L PEG solution. This could alter the results as patients ingested an equal volume of liquid (3 L) in both groups. However, if this study was eliminated, the overall results were similar (Satisfactory prep: OR 1.04, 95%CI: 0.75-1.43, P = 0.82). Additionally, a few studies utilized other adjuncts such as bisacodyl[25] and simethicone[19,21]. Given that simethicone is not a laxative, its addition in these studies likely had little impact on the quality of bowel cleansing. However, although bisacodyl is a laxative, it was given to both arms of the study, negating its overall effect. Second, a limited number of studies were used in this meta-analysis; however, all studies to-date were included in this meta-analysis using an extensive search protocol. Third, the quality of the studies was not ideal. As in most bowel preparation studies, it is very difficult to blind the patient. Therefore, these RCT’s were single-blinded to the colonoscopist, which is the optimal format for these studies. Also, three of the studies were abstracts with no data regarding method of randomization or blinding, leading to a lower Jadad score. However, these abstract studies were single-blinded randomized trials and due to word limits on abstracts, may not have presented their randomization and blinding techniques, which does not make them any less quality than other bowel prep studies. Finally, slightly different bowel prep rating systems were utilized among studies. However, all studies specifically defined satisfactory or unsatisfactory bowel preparations based upon their specific scale.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis found that a low-volume 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid administered for bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy provided equal bowel cleansing when compared to a full-dose 4 L PEG solution. However, the reduced volume of the 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid did not provide any benefit when comparing gastrointestinal side-effects including abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Therefore, the low-volume 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid can be considered as an appropriate and equally effective bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy but does not appear to offer any advantage over the traditional 4 L PEG solution. Further studies are required to compare the 2 L with ascorbic acid to the newer 4 L split-dose bowel preparation.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Colonoscopy has become a widely available screening test for both preventing and detecting CRC. However, colonoscopy requires an adequate bowel preparation for complete visualization which may induce unwanted side effects and patient discomfort.

Several studies have compared the standard bowel preparation of 4 L polyethylene glycol (PEG) to a 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid. This study is a meta-analysis comparing the above mentioned bowel preparations with regards to adequacy of the bowel preparation as well as patient side-effects during ingestion of the bowel preparation.

This is the first meta-analysis comparing 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid to 4 L PEG solution. We found that the 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid provided equal bowel cleansing when compared to a full-dose 4 L PEG solution. However, the reduced volume of the 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid did not provide any benefit when comparing gastrointestinal side-effects including abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting.

The low-volume 2 L PEG solution with ascorbic acid can be considered as an appropriate and equally effective bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy but does not appear to offer any advantage over the traditional 4 L PEG solution.

PEG is a common bowel cleansing solution that was first introduced in 1980. Standard bowel preparation using PEG typically involves ingestion of 4 L of solution prior to colonoscopy.

This is an interesting study, and a well written paper.

P- Reviewers George A, Nafiye U, Sobhonslidsuk A S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in RCA: 8967] [Article Influence: 689.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 981] [Cited by in RCA: 1059] [Article Influence: 66.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Giardiello FM, Gurbuz AK, Bayless TM, Goodman SN, Yardley JH. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: survival in patients with and without colorectal cancer symptoms. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1996;2:6-10. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Laine L, Shah A. Randomized trial of urgent vs. elective colonoscopy in patients hospitalized with lower GI bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2636-2641; quiz 2642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schusselé Filliettaz S, Juillerat P, Burnand B, Arditi C, Windsor A, Beglinger C, Dubois RW, Peytremann-Bridevaux I, Pittet V, Gonvers JJ. Appropriateness of colonoscopy in Europe (EPAGE II). Chronic diarrhea and known inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2009;41:218-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Temmerman F, Baert F. Collagenous and lymphocytic colitis: systematic review and update of the literature. Dig Dis. 2009;27 Suppl 1:137-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Parente F, Marino B, Crosta C. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy in the era of mass screening for colo-rectal cancer: a practical approach. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Swaroop VS, Larson MV. Colonoscopy as a screening test for colorectal cancer in average-risk individuals. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:951-956. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lichtenstein G. Bowel preparations for colonoscopy: a review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:27-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Barkun A, Chiba N, Enns R, Marcon M, Natsheh S, Pham C, Sadowski D, Vanner S. Commonly used preparations for colonoscopy: efficacy, tolerability, and safety--a Canadian Association of Gastroenterology position paper. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:699-710. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khalid-de Bakker CA, Jonkers DM, Hameeteman W, de Ridder RJ, Masclee AA, Stockbrügger RW. Opportunistic screening of hospital staff using primary colonoscopy: participation, discomfort and willingness to repeat the procedure. Digestion. 2011;84:281-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jung B, Lannerstad O, Påhlman L, Arodell M, Unosson M, Nilsson E. Preoperative mechanical preparation of the colon: the patient’s experience. BMC Surg. 2007;7:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | DiPalma JA, Brady CE, Pierson WP. Colon cleansing: acceptance by older patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:652-655. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Davis GR, Santa Ana CA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Development of a lavage solution associated with minimal water and electrolyte absorption or secretion. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:991-995. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hookey LC, Depew WT, Vanner SJ. Combined low volume polyethylene glycol solution plus stimulant laxatives versus standard volume polyethylene glycol solution: a prospective, randomized study of colon cleansing before colonoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:101-105. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sharma VK, Chockalingham SK, Ugheoke EA, Kapur A, Ling PH, Vasudeva R, Howden CW. Prospective, randomized, controlled comparison of the use of polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution in four-liter versus two-liter volumes and pretreatment with either magnesium citrate or bisacodyl for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | DiPalma JA, Wolff BG, Meagher A, Cleveland Mv. Comparison of reduced volume versus four liters sulfate-free electrolyte lavage solutions for colonoscopy colon cleansing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2187-2191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Pontone S, Angelini R, Standoli M, Patrizi G, Culasso F, Pontone P, Redler A. Low-volume plus ascorbic acid vs high-volume plus simethicone bowel preparation before colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4689-4695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Valiante F, Pontone S, Hassan C, Bellumat A, De Bona M, Zullo A, de Francesco V, De Boni M. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a new 2-L PEG solution plus ascorbic acid vs 4-L PEG for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:224-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Jansen SV, Goedhard JG, Winkens B, van Deursen CT. Preparation before colonoscopy: a randomized controlled trial comparing different regimes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:897-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Corporaal S, Kleibeuker JH, Koornstra JJ. Low-volume PEG plus ascorbic acid versus high-volume PEG as bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1380-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Marmo R, Rotondano G, Riccio G, Marone A, Bianco MA, Stroppa I, Caruso A, Pandolfo N, Sansone S, Gregorio E. Effective bowel cleansing before colonoscopy: a randomized study of split-dosage versus non-split dosage regimens of high-volume versus low-volume polyethylene glycol solutions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:313-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ell C, Fischbach W, Bronisch HJ, Dertinger S, Layer P, Rünzi M, Schneider T, Kachel G, Grüger J, Köllinger M. Randomized trial of low-volume PEG solution versus standard PEG + electrolytes for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:883-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | González-Méndez Y, Alarcón-Fernández O, Romero-García R, Adrián-De-Ganzo Z, Alonso-Abreu I, Carrillo-Palau M, Quintero E, Jiménez-Sosa A. Comparison of colon cleansing with two liters of polyethylen glycol-ascorbic acid versus three liters of polyethylen glycol-electrolyte: A prospective and randomized study [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:AB424. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Lee BC, Moyes DA, Mcloughlin JC, Lim PL. The efficacy, acceptability and safety of the new 2L polyethylene glycol + electrolytes + ascorbic acid (PEG + E + ASC) vs the 4L polyethylene glycol 3350 + electrolytes (PEG + E) in patients undergoing elective colonoscopies in a UK teaching hospital [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:AB290-AB291. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Clark L, Gruss HJ, Kloess HR, Dugue C, Geraint M, Halphen M, Marsh S. Better efficacy of a new 2 litre bowel cleansing preparation in the ascending colon [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:AB262. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12275] [Cited by in RCA: 12866] [Article Influence: 443.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2379] [Cited by in RCA: 2160] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kilgore TW, Abdinoor AA, Szary NM, Schowengerdt SW, Yust JB, Choudhary A, Matteson ML, Puli SR, Marshall JB, Bechtold ML. Bowel preparation with split-dose polyethylene glycol before colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1240-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |