Published online Jun 26, 2016. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v6.i2.171

Peer-review started: August 6, 2015

First decision: March 1, 2016

Revised: March 31, 2016

Accepted: April 21, 2016

Article in press: April 22, 2016

Published online: June 26, 2016

Processing time: 324 Days and 23.8 Hours

AIM: To define footwear outcomes following hallux valgus surgery, focusing on patient return to comfortable and heeled footwear and patterns of post-operative footwear selection.

METHODS: Surgical intervention is indicated for symptomatic cases of hallux valgus unresponsive to conservative methods, with favourable reported outcomes. The return to various types of footwear post-operatively is reflective of the degree of correction achieved, and corresponds to patient satisfaction. Patients are expected to return to comfortable footwear post-operatively without significant residual symptoms. Many female patients will additionally attempt to return to high-heeled, narrow toe box shoes. However, minimal evidence exists to guide their expectations. Sixty-five female hallux valgus patients that had undergone primary surgery between 2011 and 2013 were retrospectively identified using our hospital surgical database. Patients were reviewed using a footwear-specific outcome questionnaire at a mean 18.5 mo follow-up.

RESULTS: Eighty-six percent of patients were able to return to comfortable footwear post-operatively with minimal discomfort. Of those intending to resume wearing heeled footwear, 62% were able to do so, with 77% of these patients wearing these as or more frequently than pre-operatively. No significant difference was observed between pre- and post-operative heel size. Mean time to return to heeled footwear was 21.4 wk post-operation. Cosmetic outcomes were very high and did not adversely impact footwear selection.

CONCLUSION: We report high rates of return to both comfortable and heeled shoes in female patients following primary hallux valgus surgery. We observed an “all-or-none phenomenon” where patients rejected a return to heeled footwear unless able to tolerate them at the same frequency and heel size as pre-operatively. A minority of patients were unable to return to comfortable footwear post-operatively, which had adverse ramifications on their quality-of-life. We recommend that the importance of managing patient expectations through appropriate pre-operative counselling be emphasized in forefoot surgery.

Core tip: Footwear outcomes following primary hallux valgus surgery are favourable, with the majority of patients returning to comfortable footwear post-operatively with minimal to no discomfort. An additional cohort of female patients will attempt to return to heeled footwear. Nearly two-thirds of these patients tolerated heeled footwear post-operatively, the majority of these at the same heel size and frequency of use as pre-operative levels. Appropriate pre-operative counselling is imperative to achieving high patient satisfaction with footwear outcomes following hallux valgus surgery.

- Citation: Robinson C, Bhosale A, Pillai A. Footwear modification following hallux valgus surgery: The all-or-none phenomenon. World J Methodol 2016; 6(2): 171-180

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v6/i2/171.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v6.i2.171

Hallux valgus deformities (Figure 1) are one of the most common reported foot complaints, affecting greater than 35% of individuals 65+[1,2]. The prevalence is significantly higher in females and increases with advancing age[1,2]. The pathophysiology remains poorly defined, but current hypotheses implicate an interplay between genetic predisposition, initiating, and aggravating factors[2-4]. In females, the use of high-heeled narrow toe-box (HHNT) footwear (Figure 2), common in fashionable styles, has been identified as both an initiating and aggravating factor[3-5]. Patients reporting significant pain or functional impairment unresponsive to conservative methods (footwear modification, orthotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories) should be considered for joint-preserving surgical intervention (e.g., scarf ± akin osteotomy)[6-10]. The safety and efficacy of these procedures in the treatment of hallux valgus deformity is well described[6,8-13].

The return to comfortable footwear (e.g., trainers, flats, boots) is a fundamental aspect of post-operative rehabilitation and is closely related to overall patient satisfaction[8,11,14-16]. Patients are typically counselled to anticipate a period of post-operative swelling and discomfort proportional to the required degree of correction and the amount of soft tissue disruption. Previous reports suggest that patients should expect to return to comfortable footwear between 6 wk and 6 mo post-operatively, depending on operative and patient factors[6,7,11,17].

However, the evidence documenting footwear outcomes following hallux valgus surgery is limited. No studies have attempted comparison between age cohorts or procedure type. Minimal information exists on the rates of return and patterns of HHNT footwear use post-operatively. Many patients seek pre-operative information on the probability and timescales in returning to HHNT footwear. The provision of realistic, evidence-based pre-operative counselling is critical to adequately managing their expectations. The aim of our study is to determine the impact hallux valgus surgery has on patient footwear and assess the ability of female patients to return to comfortable and HHNT shoes post-operatively.

Our scientific hypothesis is that the vast majority of both working and retirement age patients will return to comfortable footwear with minimal residual symptoms. Additionally, a small cohort of patients will successfully return to wearing HHNT at pre-operative levels. The rates of return to HHNT footwear will be higher in working age patients, as will patient-reported rates of significant footwear restriction. Patients undergoing scarf procedure ± akin (alone) will have the lowest rates of post-operative footwear restriction.

Following approval from our institutional review board, we performed a retrospective review of our surgical database to identify female patients that had undergone corrective surgery for hallux valgus between January 1st, 2011 and June 28th, 2013. All patients aged 18+ operated on at our institution between these dates were included for participation in our study.

Sixty-five patients were reviewed at a mean time to follow-up of 18.5 mo (range: 6.9 to 35.9 mo). Mean patient age for our study population was 59.3 years. It is recognized that footwear selection and functional capacity varies considerably by patient age. In an attempt to identify differences between age cohorts, we segregated participants into two groups: Cohort A (18-64) - 42 individuals and cohort B (65+) - 23 individuals. While we recognized that overlap would exist in footwear selection between these cohorts, it was felt to be sufficient for rudimentary comparative analysis. In 2012, the average effective retirement age for United Kingdom females was reported to be 63.1 years by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development[18]. For the purposes of our study, 65 years was set as the cut-off between working and retired age cohorts. We additionally segregated patients by operation type, to assess its impact on footwear outcomes. Of the 65 patients, 20 underwent scarf ± akin osteotomy, 15 underwent scarf ± akin + additional joint fusion/correction and the remaining 30 were described to have undergone Lapidus tarsal-metatarsal (TMT) fusion.

A footwear-specific outcomes questionnaire was designed for the purposes of this study, in order to assess the impact that surgery had on the footwear selection of our patients (Table 1). This questionnaire was designed using elements specific to patient footwear from three validated functional scoring systems: The American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) Hallux/MTP/IP scale, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) Foot and Ankle Questionnaire, and the Manchester-Oxford Foot Questionnaire. We defined comfortable footwear as: Normal-fitting, non-prescription shoes with a heel size < 3 cm and a wide toe-box. The most common types of shoes included were trainers, flats, boots, and casual shoes. HHNT footwear was defined as: Tight-fitting shoes with a heel size ≤ 3 cm ± a narrow toe-box. Types included were pumps, wedges, platforms, slingbacks and stilettos.

| Patient study ID: | |||||||||

| Date of birth: | |||||||||

| Were you given information pre-operatively on what to expect regarding footwear following surgery? | |||||||||

| Yes/No - (Comments): | |||||||||

| What impact has foot surgery had on your choice of footwear? Are you still restricted in your footwear? | |||||||||

| Able to tolerate any footwear | |||||||||

| Able to tolerate only comfortable footwear | |||||||||

| Unable to tolerate normal, comfortable footwear | |||||||||

| (Comments): | |||||||||

| Did you wear high-heeled footwear (≥ 3cm) before your operation? Have you been able to wear these since? If so, when were you able to resume? | |||||||||

| Pre: Routine/occasional/never | Post: Routine/occasional/never | ||||||||

| (1) Heel size? | (1) Heel size? | ||||||||

| (2) Return time (in weeks): | |||||||||

| Did you desire to return to heeled footwear following your operation? | |||||||||

| Yes / No - (Comments): | |||||||||

| How would you rank the appearance of your feet pre-operatively? | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| (Comments): | |||||||||

| How would you rank the appearance of your feet post-operatively? | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| (Comments): | |||||||||

| Does the post-operative appearance (e.g., any scars or bumps) discourage you from wearing any types of footwear? | |||||||||

| Yes/No - (Comments): | |||||||||

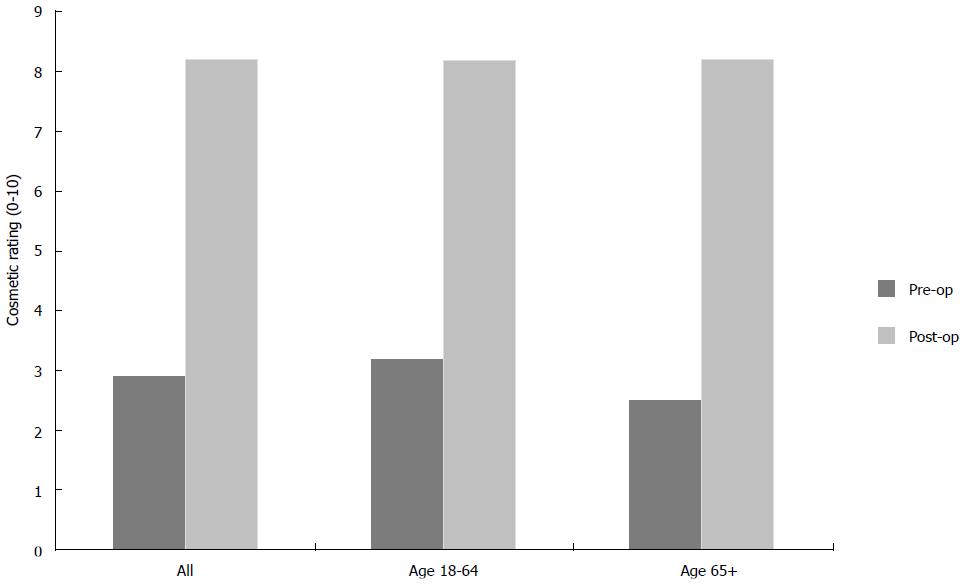

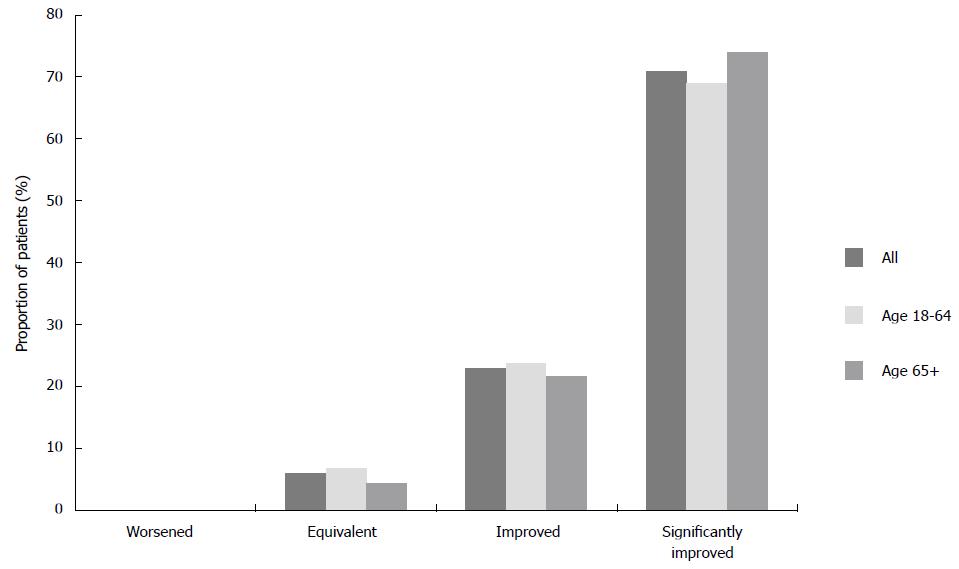

Patient-reported cosmetic appearance of the feet improved significantly following surgery, with 61 patients (93.8%) describing an improvement (Figure 3). No significant differences in cosmetic outcomes were found between cohort A (18-64) and cohort B (65+) individuals. No patients reported a worse post-operative cosmetic score. Further, 46 patients (70.8%) reported that their cosmetic appearance increased by ≥ 5 points on a 10-point global rating scale (Figure 4). Fifty-nine patients (90.7%) reported that the post-operative appearance of their feet did not adversely impact their footwear selection.

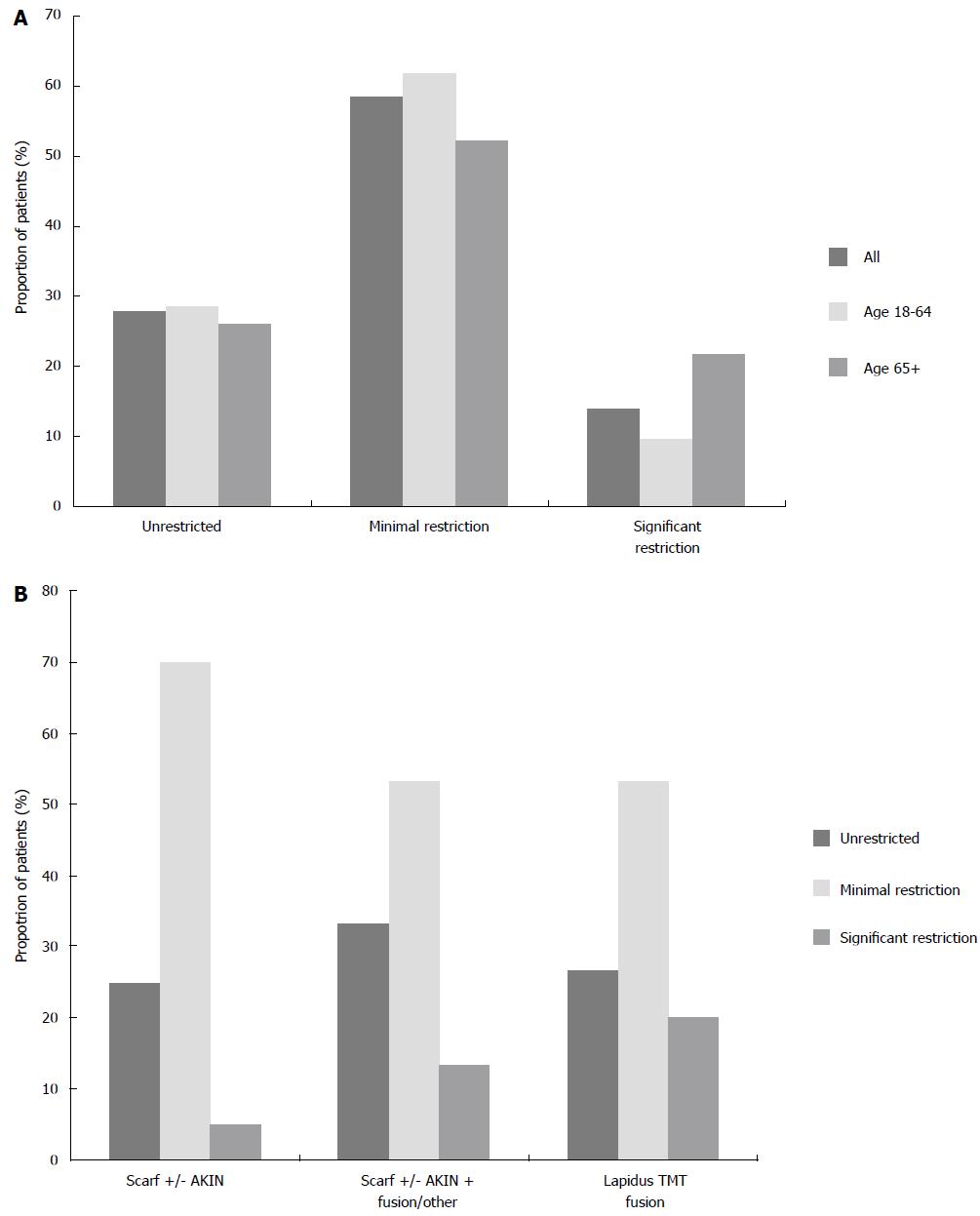

At follow-up, 38 patients (58.5%) reported minimal restriction (indicating the ability to wear comfortable shoes but difficulty with HHNT ones) (Figure 5A). A further 18 patients (27.7%) described being unrestricted in their footwear (indicating the ability to wear both comfortable as well as HHNT shoes without residual discomfort). Significant restriction (indicating the inability to wear normal, comfortable shoes without significant discomfort) was reported by 9 patients (13.9%). Those in retirement age cohort were twice as likely to report significant restriction in their footwear.

When compared by operation type, the lowest rates of significant restriction were observed following scarf ± akin operation alone - 1 patient (5%) (Figure 5B). Those that underwent scarf ± akin + additional toe fusion/correction and those that underwent Lapidus TMT fusion had higher rates of significant restriction - 2 patients (13.3%) and 6 patients (20%), respectively.

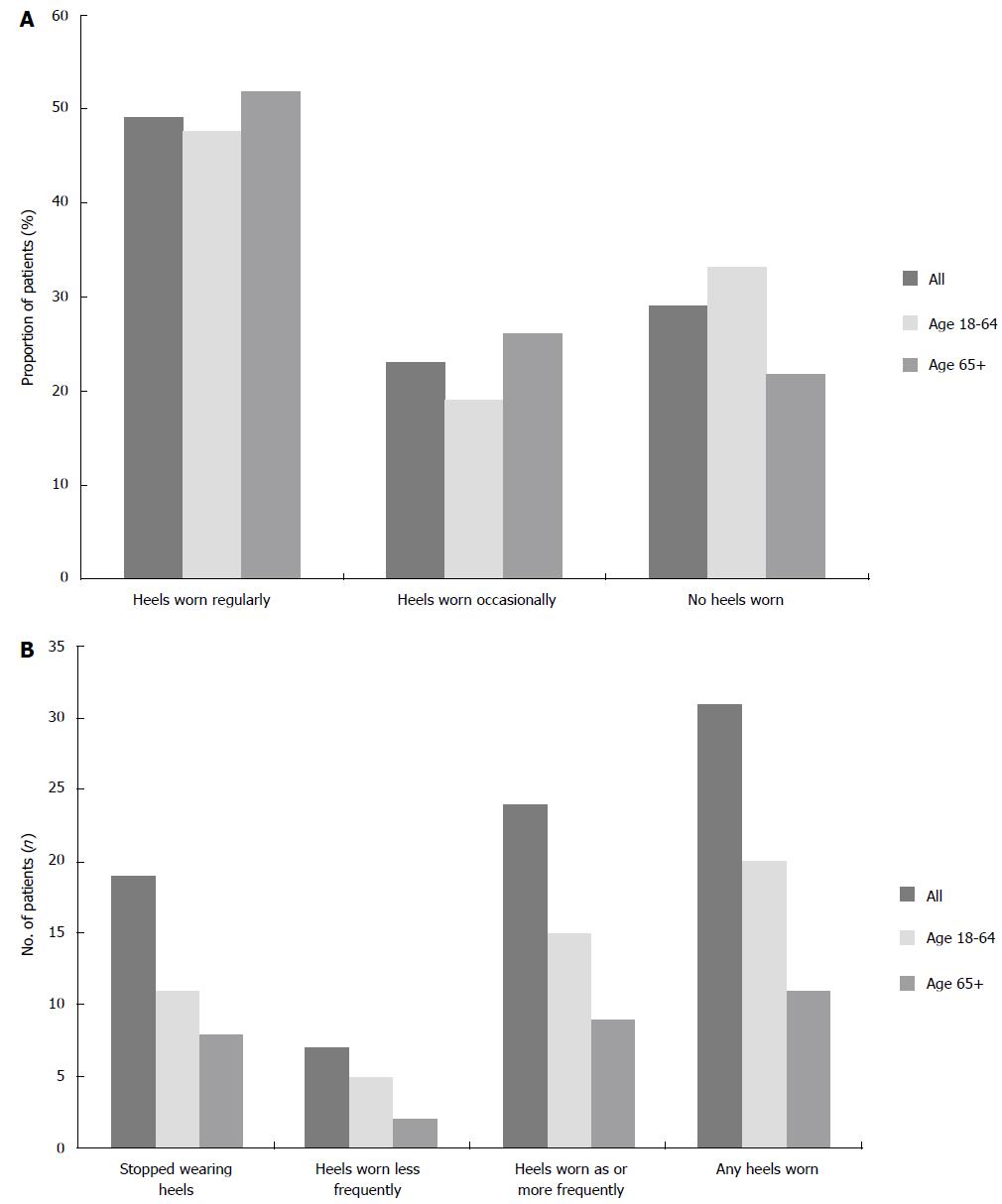

Only 19 patients (29.2%) reported minimal or no use of HHNT shoes directly before their surgery. This was related to discomfort over the medial bony prominence and/or metatarsalgia (Figure 6A). Interestingly, working age patients were less likely to have used heeled footwear pre-operatively (28 patients, 66.7%) than their retirement age counterparts (18 patients, 78.3%).

Fifty of our 65 participants (76.9%) expressed the desire to return to HHNT footwear post-operatively. Of these 50 patients, 31 (62%) reported that they had resumed use following the operation (Figure 6B). Additionally, 24 of these patients (77.4%) described use at equal or greater frequency than they had pre-operatively. Of the 19 patients that did not wear HHNT footwear pre-operatively, 4 (21.1%) began wearing them following their surgery. There was no significant difference in likelihood of patients returning to HHNT footwear post-operatively between working and retirement age cohorts.

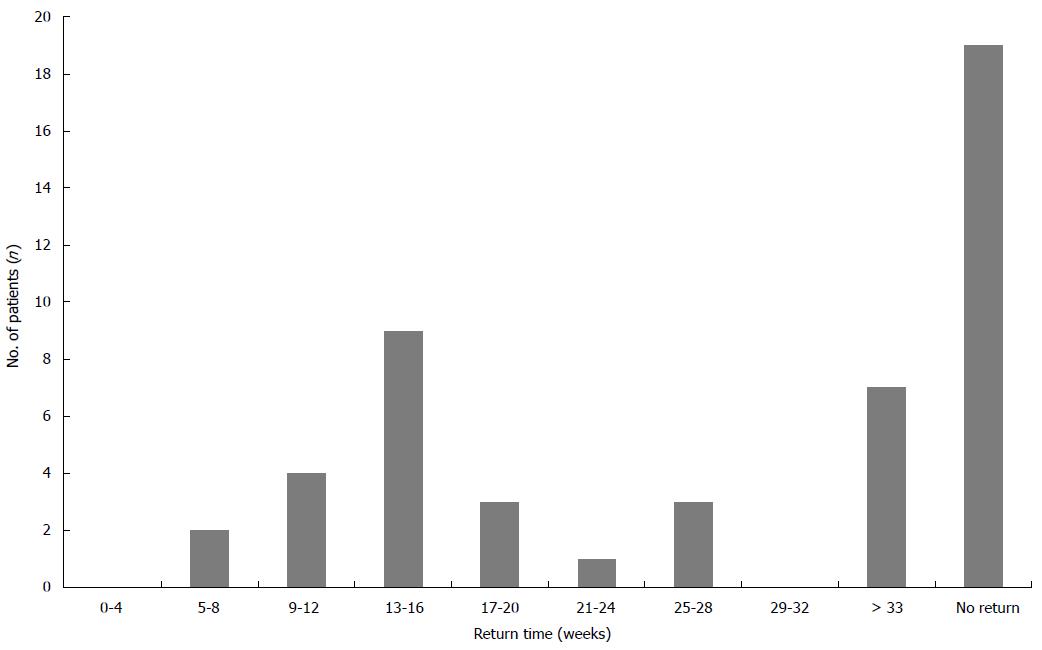

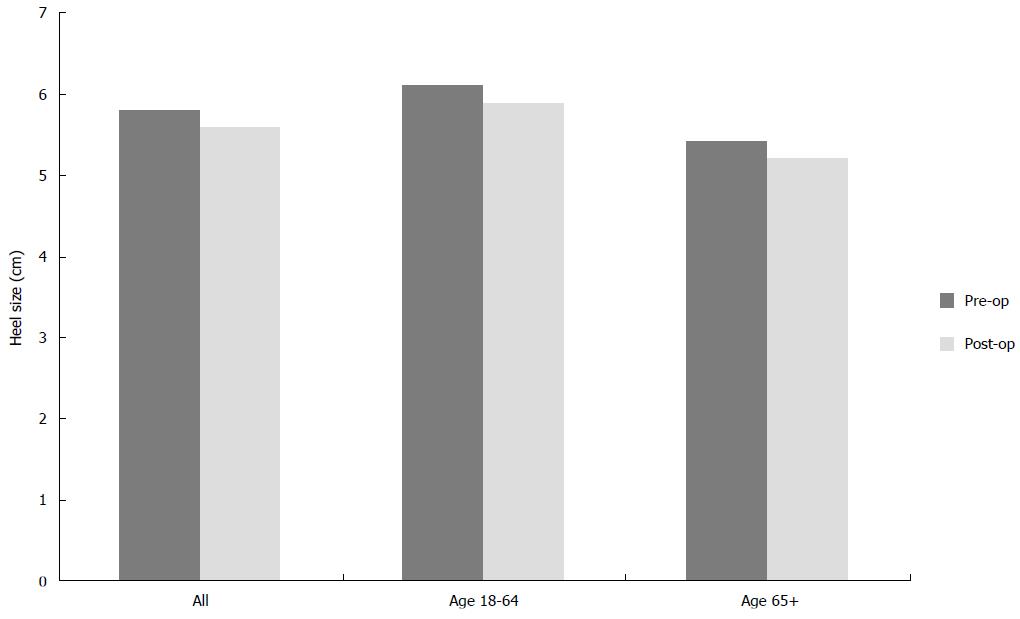

The mean time taken to return to HHNT footwear was 21.4 wk (range: 6 to 52) (Figure 7). Our retirement age cohort, however, took significantly less time to do so; 16.4 wk vs 24.1 wk (working age). Heel size remained constant following surgery and no significant difference was found pre- or post-operatively between age cohorts (Figure 8).

Footwear outcomes following hallux valgus surgery remains disputed within the literature. Adam et al[11] (2011) found an increase in AOFAS score from 61.5 pre-op to 90.3 post-op and reported that “patients returned to wearing dress shoes in 3.4 mo”. Dawson et al[15] (2007) reported that more than half of their patients expressed the importance of the ability to wear fashionable shoes with a heel > 3 cm post-operatively. At 12-mo follow-up, 62.9% were very pleased with the appearance of their foot, 72.5% were either very or fairly pleased with the range of shoes they could tolerate and 87.1% reported reduced foot pain. They found that the most critical variable to post-operative satisfaction in women was “the appearance of their foot” and that this was closely related to the “range of shoes that they were able to wear”. Thordarson et al[17] (2005) described that “postoperatively, most patients resumed fashionable or conventional shoes without an insert”. However, appraisal of their results showed that, despite overall improvement in the AAOS Foot and Ankle Core score, the standardized Shoe Comfort score remained 58.7 out of 100 at 24 mo follow-up.

Mann and Pfeffinger[19] (1991) were one of the first to report adverse footwear outcomes. They found that only 63.8% of patients were able to tolerate unrestricted footwear post-operatively. Torkki et al[9] (2001) described moderate to severe footwear restriction in 75% of their surgery cohort at 6-mo follow-up. Sixty-four point six percent continued to report these levels of restriction at 12-mo follow-up. Coetzee[16] (2003) reported unrestricted use of footwear at 12-mo follow-up in only 37% of their patients. Forty-two percent were restricted to trainers or comfortable shoes, many still reliant on orthotic inserts. Finally, Spruce et al[20] (2011) found that only 51% of participants achieved “minimally-important difference” in shoe change following surgery.

Tai et al[14] (2008) specifically focused on pre-operative patient expectations in hallux valgus surgery. They reported the ability to resume wearing normal shoes and dress shoes were ranked as the 3rd and 5th most important factors to patients, respectively, behind: (1) improved walking; and (2) reduced pain. Return to dress shoes was of greater importance to younger patients, whereas the return to comfortable shoes was ranked higher in those over age 40.

Our study demonstrated excellent post-operative cosmetic results (Figure 4). While cosmesis should not be regarded as an operative indication, improvement following surgery has been associated with high patient satisfaction and should be regarded as a desirable outcome[9,13,14].

We found that the majority of our patients were able to return to these comfortable shoes without residual discomfort, demonstrating satisfactory functional outcomes. Additionally, nearly one-third of our patients reported the ability to tolerate the unrestricted use of both comfortable and HHNT footwear, confirming the high functional capacity recovered by some patients (Figure 5A). However, 13.9% of study population reported marked difficulty wearing comfortable footwear at follow-up. These patients generally described themselves as limited to custom-built orthotic footwear or loose-fitting slippers. As anticipated, patients that had undergone additional correction procedures or fusions reported greater restriction in their post-operative footwear. Four times as many patients reported significant restriction following a Lapidus TMT fusion than following a joint-preserving scarf ± akin osteotomy alone (Figure 5B). Greater restriction in these patients is likely to correspond to increased soft tissue disruption and reduced functional mobility following surgery.

For working age patients, the impact of footwear modification on quality-of-life measures must be accounted for in pre-operative patient education. For the minority that remained significantly restricted in their footwear at follow-up, the professional and personal implications of such a limitation should not be understated. No patients in our study described an inability to return to work. However, many reported the need to modify their work environments and responsibilities for up to a year post-operatively. These observations highlight the clinical need for further investigation quantifying the impact of occupation on footwear outcomes.

In our series, the majority of patients intending to return to heeled footwear following surgery were able to do so. Further, 77.4% of these patients had increased or maintained the frequency of heel use from pre-operative levels (Figure 6B). Heel size was not found to have decreased significantly following surgery (Figure 8). These findings are suggestive of an “all-or-none phenomenon” in footwear modification following hallux valgus surgery, indicating that female patients are unlikely to resume wearing any heeled footwear until symptom resolution enables them to wear heels of the same height and frequency as they could pre-operatively.

The simplest explanation for these findings is that they are reflective of wardrobe choice, where patients choose to wear what is already available to them and are reluctant to change their footwear selection for financial or cosmetic reasons. While this undeniably plays a role in post-operative footwear modification, we suggest that the phenomenon demonstrates a more complex interaction between psychological denial of the disease state and dissatisfaction with less than complete functional recovery. Perceived fashion and societal pressures for the patient, while not always congruent with surgical outcome measures, are also likely to contribute to this finding.

As such, we suggest that our findings may misrepresent genuine functional limitation. A degree of the restriction reported is likely self-imposed by patients. This likely relates to the reluctance towards making a partial return to HHNT footwear or shifts in patient preference towards more comfortable styles. Some participants express reluctance to resume wearing heeled footwear over concerns about the possibility of disease recurrence. Many patients are aware of the association between HHNT footwear and hallux valgus deformity and this may contribute to avoidance of these footwear types as a prophylactic measure to reduce their risk of recurrence.

Following hallux valgus surgery, patients should be recommended to modify their footwear based on the residual symptoms they experience. Many patients, however, will desire to return to HHNT footwear post-operatively. There is no published evidence, at present, that the continued use of this footwear increases the risk of disease recurrence. However, the risk HHNT footwear use confers towards the development of primary hallux valgus deformity may apply equally to disease recurrence[4,21,22]. Finally, increasing heel size and smaller toe-boxes are likely to result in greater post-operative forefoot discomfort. It is therefore not advisable to recommend the frequent or prolonged use of HHNT footwear following surgery. It must, however, be accepted that for professional or personal reasons the majority of patients are likely to attempt to resume wearing HHNT footwear post-operatively. We recommend that the best approach is therefore to provide accurate and unbiased information about the likelihood of them being able to do so, as well as the potential risks involved.

Managing patient expectation and pre-operative education plays a pivotal role in outcomes following surgery to the foot and ankle. In practice, insufficient pre-operative information is likely to foster unrealistic expectations about post-operative footwear outcomes. In those patients requesting surgical intervention that are still able to achieve pain relief by footwear modification from HHNT to comfortable options, the primary focus should be to manage their symptoms non-operatively. This can be justified through reinforcement of the available evidence on post-operative footwear restriction and the operative risks involved. The results of our study should serve to enhance the pre-operative clinical advice provided to patients regarding their return to comfortable and HHNT footwear following primary hallux valgus surgery.

There are a number of limitations in our study design that affect the validity and reproducibility of the results. As a retrospective case series, there is significant potential for recall bias in patient-reported symptoms and footwear use. By excluding patients ≥ 3-year post-operation we limited maximum follow-up time in an attempt to minimize the risk of bias. A further limitation of this study was that it was conducted in a single orthopaedic unit in the United Kingdom. The generalisability of our findings is limited by geographic and cultural variation in surgical practice and patient footwear selection. We suggest that our findings can reasonably be extrapolated to other developed nations with similar patterns of footwear style and use.

We recommend an increased emphasis on pre-operative patient counselling; focused on the definition and clarification of the risks and benefits of surgery, particularly as they relate to footwear modification. Female patients should be discouraged from re-introducing footwear that reproduces symptoms or delays their post-operative rehabilitation. However, those that express the desire to return to heeled footwear for personal or professional reasons should be advised that the majority of women are able to resume wearing these post-operatively. While this may discourage a small proportion of patients from undergoing surgery, it is likely to improve overall patient satisfaction in those that ultimately do undergo operation intervention.

Surgical intervention is indicated for symptomatic cases of hallux valgus unresponsive to conservative methods, with favourable reported outcomes. The return to various types of footwear post-operatively is reflective of the degree of correction achieved, and corresponds to patient satisfaction. Patients are expected to return to comfortable footwear post-operatively without significant residual symptoms. Many female patients will additionally attempt to return to high-heeled, narrow toe box shoes. However, minimal evidence exists to guide their expectations.

Few publications address post-operative footwear modification following hallux valgus surgery. However, the topic is one that frequently inquired about by patients during pre-operative counselling. Footwear outcomes have been reported to hold a strong correlation with global patient satisfaction and this warrants further investigation.

The study focuses specifically on footwear modification following hallux valgus surgery, defining rates of return to comfortable and high-heeled narrow toe-box (HHNT) footwear and qualifying patterns of use. Additionally, the study is the first to stratify by age cohort and operation type.

The authors’ findings will help guide pre-operative patient counselling regarding footwear modification after hallux valgus surgery. This will enable clinicians to assist patients in setting realistic expectations over the end-points and timing of their functional recovery.

HHNT footwear was defined for the purposes of this study as: Tight-fitting shoes with a heel size ≤ 3 cm ± a narrow toe-box.

This is a well written study with straight forward methodology and results.

P- Reviewer: Baums MH, Robertson GA, SooHoo NF S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Nix S, Smith M, Vicenzino B. Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010;3:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Menz HB, Morris ME. Footwear characteristics and foot problems in older people. Gerontology. 2005;51:346-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nguyen US, Hillstrom HJ, Li W, Dufour AB, Kiel DP, Procter-Gray E, Gagnon MM, Hannan MT. Factors associated with hallux valgus in a population-based study of older women and men: the MOBILIZE Boston Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:41-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Perera AM, Mason L, Stephens MM. The pathogenesis of hallux valgus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:1650-1661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Coughlin MJ, Jones CP. Hallux valgus: demographics, etiology, and radiographic assessment. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:759-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Easley ME, Trnka HJ. Current concepts review: hallux valgus part II: operative treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:748-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wülker N, Mittag F. The treatment of hallux valgus. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:857-867; quiz 868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Robinson AH, Limbers JP. Modern concepts in the treatment of hallux valgus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1038-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Torkki M, Malmivaara A, Seitsalo S, Hoikka V, Laippala P, Paavolainen P. Surgery vs orthosis vs watchful waiting for hallux valgus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2474-2480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Thomas S, Barrington R. Hallux valgus. Current Orthopaedics. 2003;17:299-307. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Adam SP, Choung SC, Gu Y, O’Malley MJ. Outcomes after scarf osteotomy for treatment of adult hallux valgus deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:854-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lipscombe S, Molloy A, Sirikonda S, Hennessy MS. Scarf osteotomy for the correction of hallux valgus: midterm clinical outcome. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;47:273-277. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Coughlin MJ, Jones CP. Hallux valgus and first ray mobility. A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1887-1898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tai CC, Ridgeway S, Ramachandran M, Ng VA, Devic N, Singh D. Patient expectations for hallux valgus surgery. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2008;16:91-95. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Dawson J, Coffey J, Doll H, Lavis G, Sharp RJ, Cooke P, Jenkinson C. Factors associated with satisfaction with bunion surgery in women: A prospective study. Foot (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2007;17:119-125. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Coetzee JC. Scarf osteotomy for hallux valgus repair: the dark side. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:29-33. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Thordarson D, Ebramzadeh E, Moorthy M, Lee J, Rudicel S. Correlation of hallux valgus surgical outcome with AOFAS forefoot score and radiological parameters. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:122-127. [PubMed] |

| 18. | OECD Development. Statistics on average effective age and official age of retirement in OECD countries. [updated 2012 Oct 24]. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/ageingandemploymentpolicies-statisticsonaverageeffectiveageofretirement.htm. |

| 19. | Mann RA, Pfeffinger L. Hallux valgus repair. DuVries modified McBride procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(272): 213-218. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Spruce MC, Bowling FL, Metcalfe SA. A longitudinal study of hallux valgus surgical outcomes using a validated patient centred outcome measure. Foot (Edinb). 2011;21:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alvarez R, Haddad RJ, Gould N, Trevino S. The simple bunion: anatomy at the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe. Foot Ankle. 1984;4:229-240. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Deveci A, Firat A, Yilmaz S, Oken OF, Yildirim AO, Ucaner A, Bozkurt M. Short-term clinical and radiologic results of the scarf osteotomy: what factors contribute to recurrence? J Foot Ankle Surg. 2013;52:771-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |