Published online Mar 26, 2016. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v6.i1.87

Peer-review started: September 6, 2015

First decision: November 11, 2015

Revised: January 11, 2016

Accepted: February 16, 2016

Article in press: February 17, 2016

Published online: March 26, 2016

Processing time: 202 Days and 4.1 Hours

“Perivascular epithelioid cutaneous” cell tumors (PEComa) are a family of mesenchymal tumors with shared microscopic and immunohistochemical properties: They exhibit both smooth muscle cell and melanocytic differentiation. Non-neoplastic counterpart of PEComa’s cells are unknown, as well as the relationship between extracutaneous PEComa and primary cutaneous ones. We will review the clinical setting, histopathologic features, chromosomal abnormalities, differential diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous PEComa.

Core tip: We provide a comprehensive review of a rare neoplasm, cutaneous perivascular epithelioid cell tumor.

- Citation: Llamas-Velasco M, Requena L, Mentzel T. Cutaneous perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A review on an infrequent neoplasm. World J Methodol 2016; 6(1): 87-92

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v6/i1/87.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v6.i1.87

“Perivascular epithelioid cutaneous” cell tumors (PEComa) are a family of mesenchymal tumors with shared microscopic and immunohistochemical properties (they exhibit both smooth muscle cell and melanocytic differentiation)[1].

This term, PEComa, introduced by Zamboni et al[2], includes a group of tumors with distinctive perivascular epithelioid cells such as angyomiolipomas, lymphangiomyomatosis, clear cell sugar tumor of the lung and the so-called PEComa, that have been described in various organs and tissues, including the skin[3-13]. In any case, PEComa are exceedingly rare; have been described in the pancreas[2], pelvic cavity[14], uterus[15], prostate[16], urinary bladder[17], digestive tract[18], vulva[18], heart[18], trachea[19], lymph node[7], breast[20], bone[21] and soft tissues[22]. Moreover, tumors fitting the definition of PEComa have been reported under different names, including “clear cell myomelanocytic tumor”, “abdominopelvic sarcoma of perivascular epithelioid cells” and “primary extrapulmonary sugar tumor”[13].

First “legitimate” cutaneous PEComa was reported by Mentzel et al[9] as an abstract. After that, several other reports appeared, as well as the first series of cutaneous PEComa[9].

The most characteristic histopathologic feature of these neoplasms is that they are composed of epithelioid cells with a clear or granular cytoplasm that tend to be arranged in perivascular fashion[1].

Normal counterpart of PEComa’s cells is unknown, but there are several hypotheses including: (1) a differentiation line close to undifferentiated cells of the neural crest; (2) a myoblastic origin along with a molecular alteration that led to a melanogenesis activation; or (3) as a third option, a pericytic cell origin. Furthermore, the relationship between extracutaneous PEComa and primary cutaneous ones remains uncertain[23].

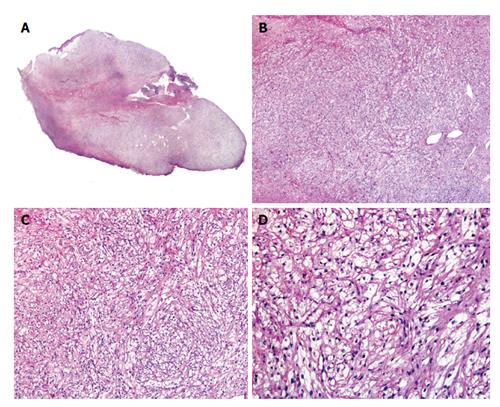

PEComa, as stated previously, are rare tumors, preferably located in subcutaneous soft tissues in the female genital tract or in the thorax (Figure 1). Cutaneous ones account for just 8% of cases, located mostly on the lower leg and, less commonly, on the forearm or the back. They usually behave in a benign fashion[8], although malignant examples have also been reported[7]. They typically appear in middle-aged adult females[24]. In our review of literature, we have found described 34 “legitimate” primary cutaneous PEComa[23]. Some of these neoplasms may be associated with tuberous sclerosis complex[4] but cutaneous lesions are mostly solitary lesions with no other associated anomalies[24].

Cutaneous PEComa presents usually as a well-demarcated dermal lesion that can extend to subcutis, composed of epithelioid cells with a large, clear or slightly granular cytoplasm and centrally located nuclei arranged in nested or trabecular pattern (Figure 2)[13]. These cells are usually arranged around the vessels, which in cutaneous PEComa are present as a rich network that may range from thin capillaries to hyalinized arterioles[7]. Up to 15% of PEComa present cords of neoplastic cells in a desmoplastic stroma[25]. PEComa’s cells can also become vacuolated. There have been descriptions of PEComa with presence of multinucleated giant cells and with some degree of nuclear pleomorphism, which have been named as symplastic PEComa[4]. Although pure spindle cell variants may be found, usually spindle cells are intermingled with the epithelioid cells and usually appear in the deeper areas of the neoplasm. Some PEComa may present with slightly pleomorphic multinucleated giant cells with few or no mitotic figures. The more characteristic feature of perivascular epithelioid cells in PEComa is their immunophenotype, which exhibits both smooth muscle cell and melanocytic markers. PEComa express melanocytic markers such as: (1) HBM45 [human melanoma black 45, the most sensitive (expressed in 100% of reported PEComa[8])]; (2) Melan A (72%); and (3) MiTF in most cases. They also express smooth muscle markers such as desmin (typically in a greater degree in cutaneous PEComa when compared with their visceral counterparts[24]); and smooth muscle actin (SMA), that may be the most sensitive marker within this group[4,26-28]. It is important to underline that up to 30% of visceral PEComa stain positive with S100 protein[4].

Pusiol et al[29] have recently published a case of a HMB-45 negative tumor that they have named PEComa. In our opinion: (1) microphotographs accompanying this paper are of insufficient quality; and (2) the authors only describe positivity for CD68 and NKI-C3 in neoplastic cells, with no information about immunohistochemical results for muscular markers, such as SMA and desmin; therefore, the diagnosis of PEComa for this case is doubtful[29].

PEComa are characteristically negative for epithelial markers despite their morphologic epithelioid features. Both types of cells, epithelioid and fusiform ones, may express CD1a and cyclin D1[30]. Ultrastructural studies showed that PEComa’s cells contain a large cytoplasm with microfilament bundles showing electron-dense condensations, numerous mitochondria and membrane-bound dense granules that match premelanosomas[12,26,27].

PEComa’s duality lets cells modulate their morphology and immunophenotype. Cases composed mainly of spindled cells usually show a strong expression of actin, but only focal expression of HMB45, whereas cases composed of clear cells usually show strong expression of HMB45 and actin is negative or only focally positive.

Finally, only a few malignant cutaneous PEComa have been reported[7,31]; one of them a scalp lesion that lately metastasized to a regional lymph node[7].

Criteria for diagnosis of “malignant PEComa” have been proposed by Folpe et al[4] (Table 1).

| Features | Definition |

| Tumor size greater than 5 cm | |

| Infiltrative growth pattern | Benign (none criteria) |

| High nuclear grade | Malignant (2 or more features) |

| Necrosis | Uncertain malignant potential (1) |

| Mitotic activity > 1/50 high power field | |

| Aggressive clinical behavior |

Recently, recurrent chromosomal alterations have been demonstrated in visceral PEComa. They are related to the genetic alterations of “tuberous sclerosis complex” [due to losses of TSC1 (9q34), TSC2 (16p13.3)], which seem to have a role in the regulation of the Rheb/mTOR/p70S6K pathway[12]. TSC1 is a tumor suppressor gene encoding for hamartin, which creates a complex with TSC2 protein (tuberin) thus with an important role in the mTORC1 pathway.

In the skin, chromosomal losses may be found[5], as well as alterations on chromosome 16p (TSC2); this has been previously reported in angiomyolipomas[5] and also in visceral PEComa, but to date has not been found in the cutaneous lesions, thus lacking evidence of a link between cutaneous PEComa and tuberous sclerosis complex[32]. In visceral PEComa these alterations produce a constitutive activation of the mTORC1 pathway[33]. Some soft tissue PEComa in patients without tuberous sclerosis complex are immunohistochemically positive for TFE3[34,35], but these findings have not yet been detected in cutaneous PEComa, a feature that suggests that the histogenesis of cutaneous PEComa might be different from the visceral ones[36].

Finally, a recent study of Charli-Joseph et al[23] using array-based comparative genomic hybridization and a complete immunohistochemical study in 8 cases of primary cutaneous PEComa did not find any chromosomal imbalances or initiating mutations. After their ample immunohistochemical study they have proposed a panel including MITF, NKIC3, SMA, desmin, bcl-1, cathepsin K and 4EB-protein 1 (4EBP1) as the ideal immunohistochemical panel for the evaluation of these neoplasms[23]. The most interesting immunohistochemical marker within this panel is 4EBP1, as it is a downstream target in the mTOR pathway[37], suggesting, when positive, an activation of the pathway independently of the mutational status of TSC1/TSC2[23].

Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor is now included within the PEComa group[9,38], as the previously described as clear cell dermatofibroma[39] although it was considered a different neoplasm for a while[10,40].

Cutaneous PEComa should be differentiated from xanthomatous lesions, granular cell tumors, myoepithelioma, cutaneous meningioma, epithelioid sarcoma, melanocytic neoplasms with balloon cell change, clear cell sarcoma, metastatic clear cell carcinomas (particularly renal cell carcinoma), dermal clear cell tumor and from gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Xanthomas may be a manifestation of hyperlipidemia; they are histopathologically characterized by a dermal collection of foamy histiocytes and thus they are positive for CD68, CD163 and, in some cases, for adipophilin[41].

Granular cell tumors cells are characterized by a prominent cytoplasm replete with eosinophilic, PAS positive, diastase-resistant granules immunohistochemically characterized for the expression of S-100 protein, PGP9.5, NKIC3, CD68, nerve growth factor receptor 75 and SOX10, which differs from the immunophenotype usually found in cutaneous PEComa; although both neoplasms share MITF-1 positivity the rare congenital granular cell tumors show also richly vascularized stroma[42,43]. In any case, to make the diagnosis even trickier, granular cell tumors may present clear-cell areas, usually as a focal finding, but sometimes occupying most of the tumor[44].

Myoepitheliomas are composed of polygonal shaped cells positive for EMA, calponin, AE1/AE3, SMA and desmin, and S100 protein; but negative for HMB-45, melan-A, tyrosinase and MITF[45].

Primary extracraneal meningioma often presents islands of clear cells and the distinction from cutaneous PEComa is usually straightforward, but as this tumor is typically EMA positive, with a variable positivity for S-100 protein and HMB45 negative, immunohistochemistry may be a useful tool in doubtful cases[46,47].

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant neoplasm characterized by polygonal cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm positive for high and low weight cytokeratins, EMA and vimentin; and negative for S-100 and HMB45[48]. Characteristically, the nuclei of neoplastic cells of epithelioid sarcoma show loss of expression on INI-1.

Melanocytic neoplasms with balloon cells usually present junctional nests and express S100 protein along with other melanocytic markers. Balloon cells are usually a focal finding, although some tumors may appear entirely composed of them[49]. Even when SMA may be positive in desmoplastic melanoma[50,51], the absence of S-100 protein staining and the positivity for SMA favor the diagnosis of PEComa. Recently, a case of pigmented PEComa with presence of focal melanin pigmentation and strong positivity for HMB-45 has been published and may represent a mimicker of melanoma[52].

Neoplastic cells of clear cell sarcoma often show an eosinophilic (rather than clear) cytoplasm and, in challenging cases, the detection of t(12;22)(q13;q12), with the resultant EWSR1-ATF1 fusion product, is diagnostic. Some peculiar cases of clear cell sarcoma-like tumor of the gastrointestinal tract presents EWSR1-CREB1 instead of the more commonly found EWSR1-ATF1, thus fluorescence in situ hybridization for EWSR1 gene rearrangement may be also useful[33].

Metastatic clear cell carcinomas express cytokeratins and PEComa is negative for them. Clear cell dermal mesenchymal tumor is usually located on the legs of adults, and histopathologically shows dermal sheets of oval to polygonal cells with abundant clear to slightly granular PAS-negative cytoplasm that is also positive for NKIC3, CD68 and vimentin, whereas melanocytic and muscular markers are consistently negative[53]. Some authors consider that this tumor is possibly associated with PEComa, but still remains considerated as a different entity based on the negativity for melanocytic markers[54]. Finally, Tomasini et al[55] published a peculiar neoplasm under the name of eruptive dermal clear cell desmoplastic mesenchymal tumor with perivascular myoid differentiation. This neoplasm showed multiple perivascular spindled to oval cells, intermingled with clear and granular cells as well as prominent desmoplasia, and a high degree of capillary vessels with hemangiopericytoma-like features[55]; this tumor was positive for h-caldesmon, SMA, CD13, CD68 and NKIC3[55].

Visceral PEComa do not express CD34 or c-kit, which is in contrast with GIST. Recently a case of cutaneous metastasis from an adrenal PEComa has been reported showing the same characteristics than a primary cutaneous PEComa, thus making necessary clinicopathologic correlation for a correct diagnosis as the patient presented with widespread metastatic disease[56].

As most PEComa are benign tumors, surgical removal is curative[1].

A recent review on PEComa located on head and neck suggests that they may be more aggressive, as one of the two malignant cutaneous PEComa and one soft tissue malignant PEComa[57] were in this location.

Besides surgery, drugs inhibiting the activation of mTOR, such as rapamycin, may be useful[58-62]. As patients with tuberous sclerosis have abnormalities in the TSC2 gene and that activates mTOR leading tumorogenesis, this explain why treatment with rapamycin seems to be useful in the treatment of renal angiomyolipomas and skin lesions of this syndrome, and may be also useful in a subset of PEComa with mTOR activation.

Symplastic PEComas portend an unknown biological behaviour[63].

P- Reviewer: Chen GS, Tüzün Y S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Requena L, Kutzner H. Cutaneous PEComa. Cutaneous Soft Tissue Tumors. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer 2015; . |

| 2. | Zamboni G, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zancanaro C, Faccioli G, Gilioli E, Pederzoli P, Bonetti F. Clear cell “sugar” tumor of the pancreas. A novel member of the family of lesions characterized by the presence of perivascular epithelioid cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:722-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. PEComa: what do we know so far? Histopathology. 2006;48:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 636] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pan CC, Jong YJ, Chai CY, Huang SH, Chen YJ. Comparative genomic hybridization study of perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: molecular genetic evidence of perivascular epithelioid cell tumor as a distinctive neoplasm. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:606-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mai KT, Belanger EC. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa) of the soft tissue. Pathology. 2006;38:415-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Calder KB, Schlauder S, Morgan MB. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (‘PEComa’): a case report and literature review of cutaneous/subcutaneous presentations. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:499-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liegl B, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Primary cutaneous PEComa: distinctive clear cell lesions of skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:608-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mentzel T, Reisshauer S, Rütten A, Hantschke M, Soares de Almeida LM, Kutzner H. Cutaneous clear cell myomelanocytic tumour: a new member of the growing family of perivascular epithelioid cell tumours (PEComas). Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of seven cases. Histopathology. 2005;46:498-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Saint Aubain Somerhausen N, Gomez Galdon M, Bouffioux B, Courtin C, Theunis A, Vogeleer MN, Myant N. Clear cell ‘sugar’ tumor (PEComa) of the skin: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:441-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tan J, Peach AH, Merchant W. PEComas of the skin: more common in the lower limb? Two case reports. Histopathology. 2007;51:135-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, Zamboni G, Bonetti F. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:119-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chaplin A, Conrad DM, Tatlidil C, Jollimore J, Walsh N, Covert A, Pasternak S. Primary cutaneous PEComa. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:310-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bonetti F, Martignoni G, Colato C, Manfrin E, Gambacorta M, Faleri M, Bacchi C, Sin VC, Wong NL, Coady M. Abdominopelvic sarcoma of perivascular epithelioid cells. Report of four cases in young women, one with tuberous sclerosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:563-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vang R, Kempson RL. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (‘PEComa’) of the uterus: a subset of HMB-45-positive epithelioid mesenchymal neoplasms with an uncertain relationship to pure smooth muscle tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pan CC, Yang AH, Chiang H. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor involving the prostate. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:E96-E98. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Pan CC, Yu IT, Yang AH, Chiang H. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the urinary bladder. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:689-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tazelaar HD, Batts KP, Srigley JR. Primary extrapulmonary sugar tumor (PEST): a report of four cases. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:615-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Küng M, Landa JF, Lubin J. Benign clear cell tumor (“sugar tumor”) of the trachea. Cancer. 1984;54:517-519. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Govender D, Sabaratnam RM, Essa AS. Clear cell ‘sugar’ tumor of the breast: another extrapulmonary site and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:670-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Insabato L, De Rosa G, Terracciano LM, Fazioli F, Di Santo F, Rosai J. Primary monotypic epithelioid angiomyolipoma of bone. Histopathology. 2002;40:286-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fukunaga M. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of soft tissue: case report with ultrastructural study. APMIS. 2004;112:98-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Charli-Joseph Y, Saggini A, Vemula S, Weier J, Mirza S, LeBoit PE. Primary cutaneous perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: a clinicopathological and molecular reappraisal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1127-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Walsh SN, Sangüeza OP. PEComas: a review with emphasis on cutaneous lesions. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2009;26:123-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Sclerosing PEComa: clinicopathologic analysis of a distinctive variant with a predilection for the retroperitoneum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:493-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bonetti F, Chiodera PL, Pea M, Martignoni G, Bosi F, Zamboni G, Mariuzzi GM. Transbronchial biopsy in lymphangiomyomatosis of the lung. HMB45 for diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:1092-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Weeks DA, Malott RL, Arnesen M, Zuppan C, Aitken D, Mierau G. Hepatic angiomyolipoma with striated granules and positivity with melanoma--specific antibody (HMB-45): a report of two cases. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1991;15:563-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sangüeza OP, Walsh SN, Sheehan DJ, Orland AF, Llombart B, Requena L. Cutaneous epithelioid angiomatous nodule: a case series and proposed classification. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:16-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pusiol T, Morichetti D, Zorzi MG, Dario S. HMB-45 negative clear cell perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the skin. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20:27-29. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Adachi Y, Horie Y, Kitamura Y, Nakamura H, Taniguchi Y, Miwa K, Fujioka S, Nishimura M, Hayashi K. CD1a expression in PEComas. Pathol Int. 2008;58:169-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Greveling K, Winnepenninckx VJ, Nagtzaam IF, Lacko M, Tuinder SM, de Jong JM, Kelleners-Smeets NW. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: a case report of a cutaneous tumor on the cheek of a male patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e262-e264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pan CC, Chung MY, Ng KF, Liu CY, Wang JS, Chai CY, Huang SH, Chen PC, Ho DM. Constant allelic alteration on chromosome 16p (TSC2 gene) in perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa): genetic evidence for the relationship of PEComa with angiomyolipoma. J Pathol. 2008;214:387-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fisher C. Unusual myoid, perivascular, and postradiation lesions, with emphasis on atypical vascular lesion, postradiation cutaneous angiosarcoma, myoepithelial tumors, myopericytoma, and perivascular epithelioid cell tumor. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:73-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tanaka M, Kato K, Gomi K, Matsumoto M, Kudo H, Shinkai M, Ohama Y, Kigasawa H, Tanaka Y. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor with SFPQ/PSF-TFE3 gene fusion in a patient with advanced neuroblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1416-1420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Argani P, Aulmann S, Illei PB, Netto GJ, Ro J, Cho HY, Dogan S, Ladanyi M, Martignoni G, Goldblum JR. A distinctive subset of PEComas harbors TFE3 gene fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1395-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Llamas-Velasco M, Mentzel T, Requena L, Palmedo G, Kasten R, Kutzner H. Cutaneous PEComa does not harbour TFE3 gene fusions: immunohistochemical and molecular study of 17 cases. Histopathology. 2013;63:122-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2185] [Cited by in RCA: 2295] [Article Influence: 127.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Folpe AL, McKenney JK, Li Z, Smith SJ, Weiss SW. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the thigh: report of a unique case. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:809-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zelger BW, Steiner H, Kutzner H. Clear cell dermatofibroma. Case report of an unusual fibrohistiocytic lesion. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:483-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Requena L, Kutzner H. Dermatofibroma. Cutaneous Soft Tissue Tumors. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer 2015; 5-32. |

| 41. | Ostler DA, Prieto VG, Reed JA, Deavers MT, Lazar AJ, Ivan D. Adipophilin expression in sebaceous tumors and other cutaneous lesions with clear cell histology: an immunohistochemical study of 117 cases. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:567-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | de la Monte SM, Radowsky M, Hood AF. Congenital granular-cell neoplasms. An unusual case report with ultrastructural findings and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:57-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Pérez-González YC, Pagura L, Llamas-Velasco M, Cortes-Lambea L, Kutzner H, Requena L. Primary cutaneous malignant granular cell tumor: an immunohistochemical study and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:334-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Zedek DC, Murphy BA, Shea CR, Hitchcock MG, Reutter JC, White WL. Cutaneous clear-cell granular cell tumors: the histologic description of an unusual variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:397-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial tumors of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 101 cases with evaluation of prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1183-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Brantsch KD, Metzler G, Maennlin S, Breuninger H. A meningioma of the scalp that might have developed from a rudimentary meningocele. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e792-e794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Theaker JM, Fletcher CD, Tudway AJ. Cutaneous heterotopic meningeal nodules. Histopathology. 1990;16:475-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Miettinen M, Fanburg-Smith JC, Virolainen M, Shmookler BM, Fetsch JF. Epithelioid sarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 112 classical and variant cases and a discussion of the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:934-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Aloi FG, Coverlizza S, Pippione M. Balloon cell melanoma: a report of two cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:230-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Carlson JA, Dickersin GR, Sober AJ, Barnhill RL. Desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. A clinicopathologic analysis of 28 cases. Cancer. 1995;75:478-494. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Riccioni L, Di Tommaso L, Collina G. Actin-rich desmoplastic malignant melanoma: report of three cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:537-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Navale P, Asgari M, Chen S. Pigmented perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the skin: first case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:866-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Lazar AJ, Fletcher CD. Distinctive dermal clear cell mesenchymal neoplasm: clinicopathologic analysis of five cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:273-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Ieremia E, Robson A. Cutaneous PEComa: a rare entity to consider in an unusual site. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:e198-e201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Tomasini C, Metze D, Osella-Abate S, Novelli M, Kutzner H. Eruptive dermal clear cell desmo-plastic mesenchymal tumors with perivascular myoid differentiation in a young boy. A clinical, histopathologic, immunohistochemical and electron microscopy study of 17 lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:123-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Wu J, Maki RG, Noroff JP, Silvers DN. Cutaneous metastasis of a perivascular epithelioid cell tumor. Cutis. 2014;93:E20-E21. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Lehman NL. Malignant PEComa of the skull base. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1230-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Cohen E. mTOR inhibitors. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2006;4:38-39. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Kenerson H, Dundon TA, Yeung RS. Effects of rapamycin in the Eker rat model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:67-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Lee L, Sudentas P, Donohue B, Asrican K, Worku A, Walker V, Sun Y, Schmidt K, Albert MS, El-Hashemite N. Efficacy of a rapamycin analog (CCI-779) and IFN-gamma in tuberous sclerosis mouse models. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;42:213-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Kenerson H, Folpe AL, Takayama TK, Yeung RS. Activation of the mTOR pathway in sporadic angiomyolipomas and other perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1361-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Paghdal KV, Schwartz RA. Sirolimus (rapamycin): from the soil of Easter Island to a bright future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:1046-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Yanai H, Matsuura H, Sonobe H, Shiozaki S, Kawabata K. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the jejunum. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:47-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |