Published online Sep 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.102688

Revised: December 31, 2024

Accepted: January 11, 2025

Published online: September 20, 2025

Processing time: 131 Days and 23.2 Hours

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive disease marked by degeneration of the lung’s blood vessels. As the disease progresses, the resistance to blood flow in the pulmonary arteries increases, putting a strain on the right side of the heart as it pumps blood through the lungs. PAH is characterized by changes in the structure of blood vessels and excessive cell growth. Untreated PAH leads to irreversible right-sided heart failure, often despite medical inter

Core Tip: Sotatercept is an activin receptor type IIA-Fc fusion protein that improve pulmonary artery pressure as well as cardiopulmonary function in pulmonary artery hypertension. It is administered as a subcutaneous injection every three weeks. There are three different pathways involve in pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Recently, a new pathway for pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension cellular proliferation has been discovered.

- Citation: Bajpai J, Saxena M, Pradhan A, Kant S. Sotatercept: A novel therapeutic approach for pulmonary arterial hypertension through transforming growth factor-β signaling modulation. World J Methodol 2025; 15(3): 102688

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i3/102688.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.102688

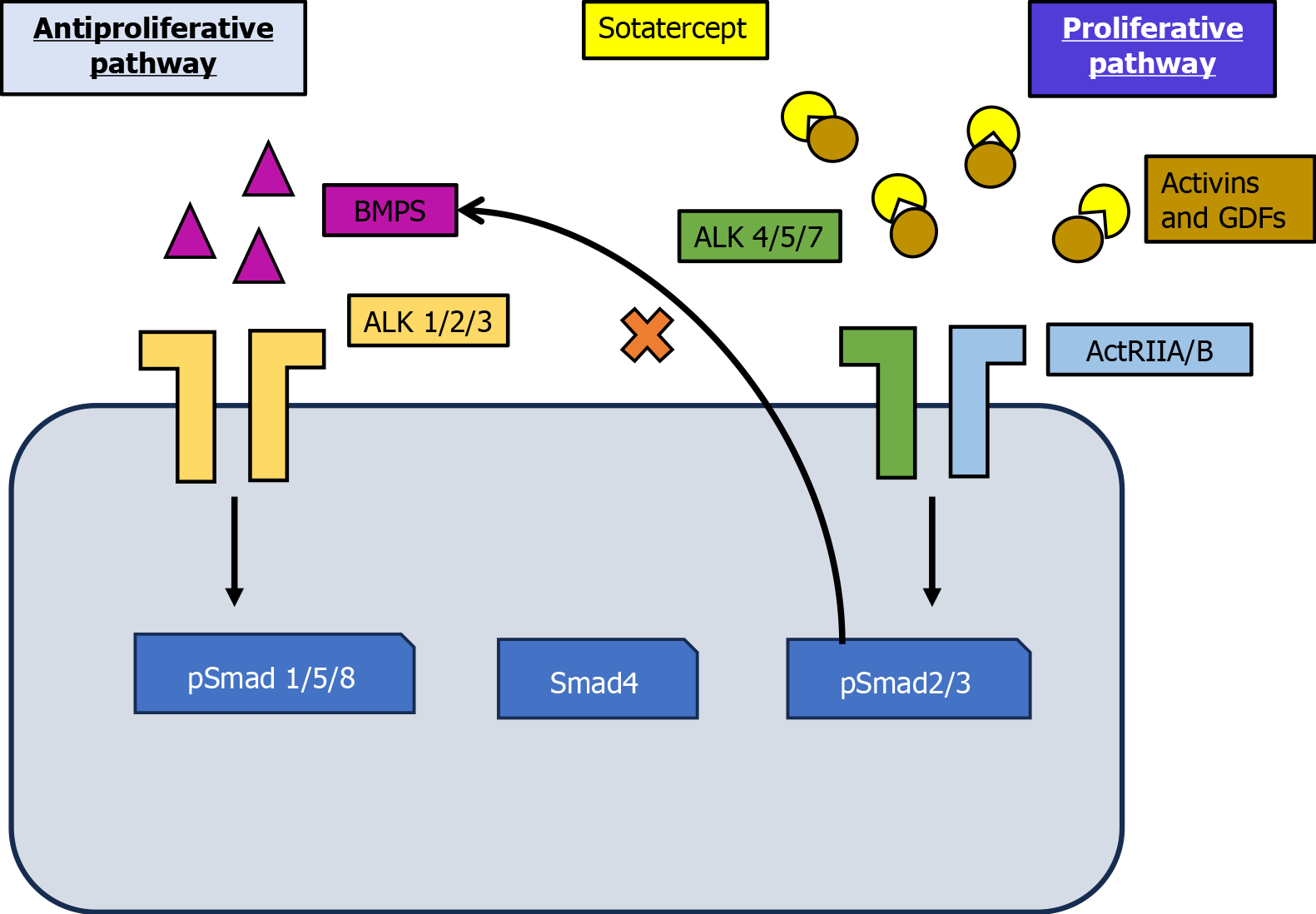

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) primarily stems from pulmonary vascular remodeling caused by an imbalance in pro- and anti-proliferative signaling pathways, leading to excessive vessel wall proliferation[1]. Impaired anti-proliferative bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II signaling in PAH allows uninhibited pro-proliferative activin signaling through activin receptor type 2A/B (ActRIIA/B)[2-4], resulting in excessive vessel wall (cell) proliferation. Existing treatment approaches for PAH primarily target three key pathways: The prostacyclin pathway using prostacyclin analogs, the endothelin pathway using endothelin receptor antagonists, and lastly the nitric oxide pathway using phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors or soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators[5-7]. While these therapies have improved symptoms and functional capacity, their ability to address the underlying vascular remodeling in PAH remains limited. Many patients fail to achieve low-risk status, and long-term survival remains poor, with a 50% 7-year survival rate post-diagnosis[7]. Moreover, these therapies primarily act as vasodilators and do not directly target the cellular and molecular mechanisms that cause disease progression. Sotatercept, a fusion protein, is believed to restore the balance between pro-proliferative and anti-proliferative signaling mediated by ActRIIA and bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II. It achieves this by binding to and sequestering specific ligands of the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily. In preclinical models of PAH, statins have demonstrated the ability to reverse pulmonary artery and right ventricle (RV) remodeling. The safety and therapeutic efficacy of sotatercept as an adjunct to baseline PAH treatment is currently being evaluated in a comprehensive clinical trial program.

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that sotatercept’s mechanism of action involves the modulation of pro- and anti-proliferative signaling pathways (Figure 1)[7]. Current PAH treatment recommendations emphasize a risk-adapted approach with combination medication therapies for the majority of patients[5,6]. With a poor 7-year survival rate after diagnosis, many patients fail to meet targeted treatment goals or achieve low-risk status, resulting in a poor long-term prognosis. Consequently, innovative therapies that directly address the underlying pathophysiology of PAH are essential to restore vascular wall homeostasis[7]. The TGF-β superfamily is central to the pathogenesis of PAH, regulating cellular proliferation and vascular remodeling. An imbalance in signaling in this superfamily contributes considerably to the vascular pathology observed in PAH. Specifically, excessive pro-proliferative drosophila mothers against decapentaplegic protein (Smad)2/3 signaling occurs alongside diminished antiproliferative Smad1/5/8 signaling, driving pathological vascular remodeling[8].

Activin-class ligands, including activin A, growth differentiation factor (GDF) 8, and GDF11, are key activators of the Smad2/3 signaling pathway. These ligands are considerably upregulated in the small pulmonary arteries of both experimental models and PAH patients[4]. Sotatercept, an Fc-fusion protein containing the extracellular domain of ActRIIA, sequesters activin-class ligands, thereby restoring the balance between Smad2/3 and Smad1/5/8 signaling. This rebalancing produces antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory effects on the pulmonary vasculature, reversing vascular remodeling and reducing pulmonary hypertension in preclinical models of PAH[9].

Moreover, studies have implicated activin receptor signaling in the abnormal remodeling of the RV, which is a critical indicator of prognosis in PAH[10]. In preclinical models of systemic pressure overload, ischemia, and aging, activin receptor signaling has been linked to detrimental RV remodeling[11]. By regulating this pathway, sotatercept could potentially mitigate RV dysfunction, as suggested by clinical trial observations of RV function improvements. Distinct from conventional vasodilator-based treatments that primarily focus on hemodynamic parameters, sotatercept’s capacity to address the underlying mechanisms of vascular and RV remodeling classifies it as a disease-modifying agent. The therapeutic application of engineered fusion proteins such as sotatercept has been extensively investigated owing to their ability to modulate crucial signaling pathways in diseases such as PAH[12]. These mechanistic insights provide a robust foundation for the therapeutic efficacy observed with sotatercept in clinical studies, even in patients receiving multiple background therapies[1].

As shown in Table 1, several clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of sotatercept in Pulmonary Hypertension.

| Study | Type of study | No. of patients | Dose | Primary end point | Adverse events | Serious adverse events | Outcome | Type of PAH | Background regimen |

| Pulsar | Phase 2 randomized, double-blind | 106 patients at 43 sites in 8 countries | 0.3 or 0.7 mg/kg-1 mg/kg | To compare the efficacy and safety of sotatercept vs placebo when added to standard of care | Thrombocytopenia was the most common; Hemoglobin increase in 1 patient (3%) in the sotatercept 0.3-mg group and in 7 patients (17%) in sotatercept 0.7-mg group but in no in the placebo group | 24% in 0.7 mg group | 162.2 dyn. sec. cm (-5) in the sotatercept 0.3-mg group and a decrease of 255.9 dyn. sec. cm (-5) in the sotatercept 0.7-mg group, as compared with a decrease of 16.4 dyn. sec. cm (-5) in placebo | Idiopathic (58%), heritable (14%), connective tissue disorder (17%), and drug induced (7%) | Prostacyclin infusion (39%), triple therapy (57%), double therapy (34%) |

| Pulsar open | Phase 2, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study | 106 participants | 0.3 mg/kg-1 mg/kg or 0.7 mg/kg-1mg/kg | Change from baseline to months 18-24 in PVR, as measured by RHC. Change from baseline to months 18-24 in 6MWD, WHO-FC, and NT-proBNP were secondary endpoints. The study protocol was amended in July 2020 with the third RHC to be performed at month 18 | TEAEs were reported in 102 (98.1%) participants, and 72 (69.2%) of these experienced TEAEs considered treatment-related | Serious TEAEs were reported in 32 (30.8%) participants. Five (4.8%) participants reported six serious TEAEs that were considered related to the study drug: Pyrexia, red blood cell increased, systemic lupus erythematosus, ischaemic stroke, pleural effusion and pulmonary hypertension | Statistically significant improvements occurred in all primary and secondary efficacy endpoints from baseline to months 18-24 | Idiopathic (58%), heritable (14%), connective tissue disorder (17%), and drug induced (7%) | Triple (56.7%) or double (36.1%) background PAH therapy, and more than a third (36%) were receiving prostacyclin infusion therapy |

| Stellar | Phase 3 randomized, double-blind | 323 underwent randomization (163 received sotatercept or 160 placebo at 91 sites in 21 countries | Starting dose of 0.3 mg/kg at visit 1 and was escalated to the target dose of 0.7 mg/kg at visit 2 (day 21, with a window of ± 3 days). Patients continued to receive a dose of 0.7 mg/kg for the duration of the trial | The change from baseline at week 24 in the 6MWD | 10% of the patients in either group during the 24-week treatment period. Epistaxis, dizziness, telangiectasia, in- creased hemoglobin levels, thrombocytopenia, and increased blood pressure were common adverse events | Serious adverse events occurred in 23 patients (14.1%) in the sotatercept group and 36 patients (22.5%) in the placebo group | Sotatercept and placebo groups the change from baseline at week 24 in the 6-minute walk distance was 40.8 m (0.001 < P) | Idiopathic (50.9%), heritable (21.5%), drug-induced (4.3%), connective-tissue disease-associated (17.8%), or after shunt correction (5.5%) | Monotherapy (5.5%), double therapy (34.4%), or triple therapy (60.1%) |

| Spectra | Phase 2 open label | 21 | Sotatercept 0.3 mg/kg | Change from baseline to week 24 in peak oxygen uptake | 16 (76%) | 3 (14%). Three serious TEAEs were reported (hematochezia, complication associated with central line, and fluid overload) | There was a significant improvement from baseline in peak oxygen uptake, with a mean change of 102.74 mL/min (95% CIs: 27.72-177.76; P = 0.0097) | Idiopathic (6%), heritable (4%). Associated with connetive tissue disorder (14%) | Prostacyclin infusion therapy (57%), double therapy (57%), triple therapy (43%) |

The safety and efficacy of sotatercept in individuals with PAH who were receiving background medication for pulmonary hypertension were investigated in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase 2 trial[1]. This trial consisted of a 24-week placebo-controlled treatment phase followed by an 18-month active medication extension period. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were classified as World Health Organization (WHO) functional class (FC) II or III and had confirmed PAH (group 1 of the latest WHO classification of pulmonary hypertension)[13]. The subtypes linked to portopulmonary disease, schistosomiasis, and human immunodeficiency virus infection were excluded. Three groups of eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive sotatercept at doses of 0.3, 0.7, or a placebo. Subcutaneous injections of sotatercept or placebo (saline) were administered every 21 days.

At week 24, the intention-to-treat analysis demonstrated a reduction in pulmonary vascular resistance from baseline in the 0.3 mg sotatercept group, with an even greater reduction in the 0.7 mg sotatercept group compared to the placebo group. The 0.7 mg sotatercept group experienced an approximately 35% reduction from baseline. The most common hematologic adverse events were thrombocytopenia and elevated hemoglobin levels. Sotatercept treatment has been shown to reduce pulmonary vascular resistance in patients receiving baseline monotherapy, double therapy, or triple therapy. The primary factor contributing to the reduction in pulmonary vascular resistance was the lower mean pulmonary artery pressure in the sotatercept groups compared to the placebo group. Additionally, the sotatercept group demonstrated concordant improvements from baseline in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels.

The study aimed to assess the safety and effectiveness of sotatercept in treating PAH. A total of 106 individuals with WHO FC II-III and WHO group 1 PAH were included. Sotatercept (0.3 mg/kg or 0.7 mg/kg) was added to the standard of care during a 24-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[14]. In the extension phase, patients receiving sotatercept continued their current dosage, while those on placebo were rerandomized to either 0.3 mg/kg or 0.7 mg/kg of sotatercept. The improvements observed in 6MWD, NT-proBNP, and WHO FC at 24 weeks compared to baseline were maintained when sotatercept treatment was continued for up to 48 weeks. Individuals who were rerandomized from placebo to sotatercept at 48 weeks rather than 24 weeks also experienced improvements in 6MWD, NT-proBNP, and WHO FC.

In phase 3 multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, eligible patients with PAH who were receiving stable background therapy and classified as WHO FC II or III were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous sotatercept every three weeks at a starting dose of 0.3 mg per kilogram of body weight (target dose: 0.7 mg per kilogram) or a placebo[15]. The primary outcome measure was the change in 6MWD from baseline at week 24. Patients with schistosomiasis, veno-occlusive disease, portopulmonary disease, and human immunodeficiency virus infection were excluded from the study. The primary outcome measure was the change in 6MWD from baseline at week 24. Secondary endpoints were ranked hierarchically. Multi-component improvement was calculated as the proportion of patients who met all three criteria at week 24 compared to baseline (i.e., an increase of at least 30 minutes in 6MWD, a decrease of at least 30% in NT-proBNP level, or maintenance or achievement of an NT-proBNP level of less than 300 pg per milliliter, or an improvement in WHO FC from III to II or I, or II to I, or II).

Out of the 434 patients screened for eligibility, 323 were randomized to receive sotatercept or placebo at 91 locations in 21 countries. Eligible patients were randomized (1:1) to receive a placebo (160 patients) or sotatercept (163 patients) in addition to their ongoing background therapy. The study population was relatively young, with a mean age of 47.9 years and a mean time from diagnosis of 8.8 years. Among the 323 patients randomized, 198 (61.3%) were receiving triple therapy, and 129 (39.5%) were receiving prostacyclin infusion therapy. During the 24-week treatment period, at least 10% of patients in both groups reported experiencing adverse events. Epistaxis, telangiectasia, and dizziness were more common in the sotatercept group than in the placebo group.

In the sotatercept group, 23 patients (14.1%) experienced serious adverse events, compared to 36 patients (22.5%) in the placebo group. Mean hemoglobin levels increased by approximately 1.3 g/dL in the sotatercept group and decreased by approximately 0.1 g/dL in the placebo group at week 24. Addition of sotatercept to background therapy with currently available medications for 24 weeks was found to improve exercise capacity as measured by 6MWD. Improvements were also observed in pulmonary vascular resistance, WHO FC, NT-proBNP levels, risk of death, and the physical impacts and cardiopulmonary and symptoms domain scores of the PAH-symptoms and impact quality-of-life instrument. Sotatercept was associated with an 84% reduced risk of death or nonfatal clinical deterioration events compared to placebo. The safety profile of sotatercept was consistent with findings from the phase 2 pulsar study. The study had several limitations, including the underrepresentation of minority groups, patients from outside North America and Europe, and patients with PAH associated with drugs and toxins, congenital heart disease, or connective tissue disease. According to study results, patients with PAH may experience a nearly three-fold increase in life expectancy when sotatercept is added to stable background therapy. This benefit may be accompanied by a reduction in the need for lung/heart-lung transplantation, intravenous prostacyclin, and PAH-related hospitalizations.

In the BELIEVE phase 2 trial, sotatercept was evaluated in patients with beta-thalassemia. Results showed that sotatercept considerably increased hemoglobin levels and reduced transfusion burden in patients with beta-thalassemia, suggesting a potential benefit in treating anemia in this patient population. Additionally, levastaruzent is being studied in a phase 3 trial called medalist (NCT02631070) in patients with very low-, low-, and intermediate-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Despite the discontinuation of sotatercept’s trials in β-thalassemia owing to its binding to activin A, sotatercept is the first-in-class agent to target TGF-β superfamily inhibition for the treatment of ineffective erythropoiesis. For patients with β-thalassemia, TGF-β superfamily inhibition may provide an alternative or adjunctive therapeutic approach[16]. In this study, sotatercept demonstrated safety and efficacy in patients with β-thalassemia. In a phase 2 study, sotatercept treatment was also found to increase hemoglobin levels and reduce transfusion requirements in anemic patients with lower-risk MDS[17]. These findings suggest that sotatercept may have a common underlying mechanism of action that ameliorates ineffective erythropoiesis across multiple disease states.

Sotatercept has been investigated in numerous clinical trials across various therapeutic areas, with a focus on its potential to treat conditions such as MDS, PAH, and others. In the commands trial, sotatercept was found to improve anemia and reduce the need for red blood cell transfusions in patients with lower-risk MDS. These findings suggest that sotatercept may be a promising therapeutic option for patients with MDS. The cherish trial demonstrated that sotatercept could improve iron overload markers and increase hemoglobin levels in patients with non-transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic option for this patient population. Collectively, these studies indicate that sotatercept holds promise for the treatment of various conditions characterized by anemia, impaired red blood cell production, and related complications.

The ongoing, open-label extension study, SOTERIA, is evaluating the long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of sotatercept when added to background therapy for the treatment of PAH in patients who have completed prior sotatercept studies without premature discontinuation[18]. SPECTRA is a phase 2, open-label trial evaluating the change in peak oxygen consumption during exercise in adult PAH patients[19]. Similarly, MOONBEAM and CADENCE are ongoing phase 2 trials investigating the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of sotatercept, as well as its role in reducing pulmonary vascular resistance, respectively[20-22]. The hyperion and zenith trials are randomized, controlled phase 3 studies evaluating the effect of sotatercept on time to clinical worsening or first morbidity or mortality events[20].

The clinical translation of sotatercept for PAH faces several challenges that need to be addressed to ensure its effective implementation. One considerable hurdle lies in the high cost of biological therapies. Sotatercept, as a complex biologic, may carry a substantial price tag, particularly in resource-constrained settings. This could limit access to the drug for patients in low- and middle-income countries where healthcare resources are often limited. Overcoming this challenge will require exploring cost-effective manufacturing methods and advocating for policy changes that can improve affordability and accessibility, thus ensuring broader availability for those in need. Another challenge lies in managing the potential side effects associated with sotatercept. Despite its promising effects in reversing vascular remodeling, clinical trials have reported adverse events, including thrombocytopenia and elevated hemoglobin levels. These side effects require careful monitoring and effective management strategies to ensure patient safety. Establishing standardized protocols for patient monitoring, encompassing strategies for early detection and intervention, will be crucial to minimizing risks and optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

Ultimately, the successful clinical implementation of sotatercept depends on its integration into existing healthcare frameworks. This entails timely and accurate diagnosis of PAH, providing adequate training for clinicians on its use, and incorporating sotatercept into established treatment protocols. Ensuring that healthcare systems possess the necessary infrastructure to effectively manage these novel treatment options is paramount to maximizing their benefits and improving patient outcomes. Addressing these barriers will be essential to fully realize the transformative potential of sotatercept in the treatment of PAH.

A noteworthy limitation of this study lies in the exclusion of metabolites with insufficient single nucleotide polymorphisms, an approach adopted to maintain statistical rigor and minimize the risk of false-positive associations. However, this approach may have inadvertently limited the ability to identify novel metabolite-gene associations, especially for metabolites that are understudied or lack sufficient genetic data. Future studies should consider alternative approaches, such as imputation-based methods or integrating multi-omics datasets, to improve the analysis of these metabolites. Because sotatercept, an activin signaling inhibitor, is the first medication to target a completely new pathway in nearly two decades, its inclusion in the therapeutic arsenal has considerably raised expectations. Ongoing long-term research will be critical to further understanding the drug’s overall benefits and safety profile.

Sotatercept, a novel therapeutic approach, targets the underlying pathophysiology of PAH by addressing the imbalance between pro- and anti-proliferative signaling pathways. This innovative mechanism of action sets it apart from conventional therapies, offering a new avenue for the management of PAH. Clinical trials, including pulsar, stellar, and others, have substantiated sotatercept’s efficacy in considerably reducing pulmonary vascular resistance, enhancing exercise capacity, and positively influencing key biomarkers such as NT-proBNP. Notably, its safety profile has remained consistent across studies; however, ongoing monitoring of long-term effects is warranted.

Sotatercept shows promise in enhancing patient outcomes when added to background PAH therapy. Ongoing trials, such as SOTERIA, MOONBEAM, and CADENCE, in the open-label long-term follow-up study to evaluate the effects of sotatercept in PAH treatment will offer further insights into its long-term efficacy and safety. Sotatercept’s unique mechanism of action offers a promising new direction in PAH treatment, potentially extending survival, reducing morbidity, and improving the quality of life for patients who continue to face poor prognoses despite current treatment options. However, it is important to note that much of the genetic and mechanistic data informing these advances primarily come from genome-wide association studies performed in European populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other populations and underscores the need for more diverse and representative datasets in PAH research. Addressing these gaps is crucial to ensuring that novel therapeutics such as sotatercept are broadly applicable and effective across diverse patient populations. Future research should focus on elucidating the sotatercept’s role in various PAH subgroups and exploring the potential of combination therapies to optimize outcomes. In essence, sotatercept is poised to become a key component of PAH management, addressing unmet medical needs and offering hope for patients battling this challenging condition.

| 1. | Humbert M, McLaughlin V, Gibbs JSR, Gomberg-Maitland M, Hoeper MM, Preston IR, Souza R, Waxman A, Escribano Subias P, Feldman J, Meyer G, Montani D, Olsson KM, Manimaran S, Barnes J, Linde PG, de Oliveira Pena J, Badesch DB; PULSAR Trial Investigators. Sotatercept for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1204-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 82.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tielemans B, Delcroix M, Belge C, Quarck R. TGFβ and BMPRII signalling pathways in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24:703-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Morrell NW, Aldred MA, Chung WK, Elliott CG, Nichols WC, Soubrier F, Trembath RC, Loyd JE. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yung LM, Yang P, Joshi S, Augur ZM, Kim SSJ, Bocobo GA, Dinter T, Troncone L, Chen PS, McNeil ME, Southwood M, Poli de Frias S, Knopf J, Rosas IO, Sako D, Pearsall RS, Quisel JD, Li G, Kumar R, Yu PB. ACTRIIA-Fc rebalances activin/GDF versus BMP signaling in pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaaz5660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bisserier M, Pradhan N, Hadri L. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches to pulmonary hypertension. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020;21:163-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mayeux JD, Pan IZ, Dechand J, Jacobs JA, Jones TL, McKellar SH, Beck E, Hatton ND, Ryan JJ. Management of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2021;15:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | 7 Sitbon O, Gomberg-Maitland M, Granton J, Lewis MI, Mathai SC, Rainisio M, Stockbridge NL, Wilkins MR, Zamanian RT, Rubin LJ. Clinical trial design and new therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Andre P, Joshi SR, Briscoe SD, Alexander MJ, Li G, Kumar R. Therapeutic Approaches for Treating Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension by Correcting Imbalanced TGF-β Superfamily Signaling. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:814222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | 9 Joshi SR, Liu J, Bloom T, Karaca Atabay E, Kuo TH, Lee M, Belcheva E, Spaits M, Grenha R, Maguire MC, Frost JL, Wang K, Briscoe SD, Alexander MJ, Herrin BR, Castonguay R, Pearsall RS, Andre P, Yu PB, Kumar R, Li G. Sotatercept analog suppresses inflammation to reverse experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci Rep. 2022;12:7803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Prisco SZ, Thenappan T, Prins KW. Treatment Targets for Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5:1244-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Magga J, Vainio L, Kilpiö T, Hulmi JJ, Taponen S, Lin R, Räsänen M, Szabó Z, Gao E, Rahtu-Korpela L, Alakoski T, Ulvila J, Laitinen M, Pasternack A, Koch WJ, Alitalo K, Kivelä R, Ritvos O, Kerkelä R. Systemic Blockade of ACVR2B Ligands Protects Myocardium from Acute Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Mol Ther. 2019;27:600-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen Y, Feng H, Chen L, Zhou W, Zhou S. Construction of homologous branched oligomer megamolecules based on linker-directed protein assembly. Soft Matter. 2024;20:6889-6893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | 13 Pitre T, Su J, Cui S, Scanlan R, Chiang C, Husnudinov R, Khalid MF, Khan N, Leung G, Mikhail D, Saadat P, Shahid S, Mah J, Mielniczuk L, Zeraatkar D, Mehta S. Medications for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31:220036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Humbert M, McLaughlin V, Gibbs JSR, Gomberg-Maitland M, Hoeper MM, Preston IR, Souza R, Waxman AB, Ghofrani HA, Escribano Subias P, Feldman J, Meyer G, Montani D, Olsson KM, Manimaran S, de Oliveira Pena J, Badesch DB. Sotatercept for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: PULSAR open-label extension. Eur Respir J. 2023;61:2201347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hoeper MM, Badesch DB, Ghofrani HA, Gibbs JSR, Gomberg-Maitland M, McLaughlin VV, Preston IR, Souza R, Waxman AB, Grünig E, Kopeć G, Meyer G, Olsson KM, Rosenkranz S, Xu Y, Miller B, Fowler M, Butler J, Koglin J, de Oliveira Pena J, Humbert M; STELLAR Trial Investigators. Phase 3 Trial of Sotatercept for Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1478-1490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 158.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cappellini MD, Porter J, Origa R, Forni GL, Voskaridou E, Galactéros F, Taher AT, Arlet JB, Ribeil JA, Garbowski M, Graziadei G, Brouzes C, Semeraro M, Laadem A, Miteva D, Zou J, Sung V, Zinger T, Attie KM, Hermine O. Sotatercept, a novel transforming growth factor β ligand trap, improves anemia in β-thalassemia: a phase II, open-label, dose-finding study. Haematologica. 2019;104:477-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Komrokji R, Garcia-Manero G, Ades L, Prebet T, Steensma DP, Jurcic JG, Sekeres MA, Berdeja J, Savona MR, Beyne-Rauzy O, Stamatoullas A, DeZern AE, Delaunay J, Borthakur G, Rifkin R, Boyd TE, Laadem A, Vo B, Zhang J, Puccio-Pick M, Attie KM, Fenaux P, List AF. Sotatercept with long-term extension for the treatment of anaemia in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a phase 2, dose-ranging trial. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e63-e72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. |

|

| 19. | Waxman AB, Systrom DM, Manimaran S, de Oliveira Pena J, Lu J, Rischard FP. SPECTRA Phase 2b Study: Impact of Sotatercept on Exercise Tolerance and Right Ventricular Function in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circ Heart Fail. 2024;17:e011227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Torbic H, Tonelli AR. Sotatercept for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in the Inpatient Setting. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2024;29:10742484231225310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Auth R, Klinger JR. Emerging pharmacotherapies for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2023;32:1025-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pradhan A, Tyagi R, Sharma P, Bajpai J, Kant S. Shifting Paradigms in the Management of Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur Cardiol. 2024;19:e25. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |