Published online Sep 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.102477

Revised: January 11, 2025

Accepted: January 21, 2025

Published online: September 20, 2025

Processing time: 138 Days and 19.4 Hours

Emergency medical care is essential in preventing morbidity and mortality, especially when interventions are time-sensitive and require immediate access to supplies and trained personnel.

To assess the treatment rates of eye emergencies in Africa. Ocular emergencies are particularly delicate due to the eye’s intricate structure and the necessity for its refractive components to remain transparent.

This review examines the low treatment rates of eye emergencies in Africa, drawing on 96 records extracted from the PubMed database using predetermined search criteria.

The epidemiology of ocular injuries, as detailed in the studies, reveals significant relationships between the incidence and prevalence of eye injuries and factors such as age, gender, and occupation. The causes of eye emergencies range from accidents to gender-based violence and insect or animal attacks. Management approaches reported in the review include both surgical and non-surgical interventions, from medication to evisceration or enucleation of the eye. Preventive measures emphasize eye health education and the use of protective eyewear and facial protection. However, inadequate healthcare infrastructure and personnel, cultural and geographical barriers, and socioeconomic and behavioral factors hinder the effective prevention, service uptake, and management of eye emergencies.

The authors recommend developing eye health policies, enhancing community engagement, improving healthcare personnel training and retention, and increasing funding for eye care programs as solutions to address the low treatment rate of eye emergencies in Africa.

Core Tip: Eye emergencies in Africa are severely under-treated due to a combination of factors including inadequate healthcare infrastructure, shortage of trained personnel, and socio-economic and cultural barriers. This results in a high prevalence of preventable blindness. This study emphasizes the need for urgent policy reforms, increased funding, and community engagement to improve access to timely and effective eye care across the continent.

- Citation: Bale BI, Zeppieri M, Idogen OS, Okechukwu CI, Ojo OE, Femi DA, Lawal AA, Adedeji SJ, Manikavasagar P, Akingbola A, Aborode AT, Musa M. Seeing the unseen: The low treatment rate of eye emergencies in Africa. World J Methodol 2025; 15(3): 102477

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i3/102477.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.102477

Eye emergencies encompass a wide range of conditions that require immediate medical attention to prevent severe consequences, such as permanent vision loss[1]. These include acute infections like endophthalmitis and corneal ulcers, traumatic injuries such as open globe injuries and chemical burns, and sudden exacerbations of conditions like acute angle-closure glaucoma[1,2]. Timely and effective medical response is critical for these conditions, as they can rapidly worsen if not treated promptly. While eye emergencies are a global public health issue, their impact is particularly pronounced in low-resource settings, such as many regions in Africa[1].

In Africa, socio-economic barriers further exacerbate the challenge, making it difficult for many individuals, especially in rural areas, to access facilities capable of handling ocular emergencies[3]. The shortage of trained ophthalmologists and emergency eye care services worsens the situation, leading to low treatment rates for these critical conditions[4]. This inadequate response infrastructure contributes to a high prevalence of preventable blindness and underscores significant disparities in healthcare access and quality across the continent[5].

Addressing these challenges requires urgent investment in healthcare infrastructure, enhanced training for eye care professionals, and the establishment of surveillance systems to monitor the health situation[7,8]. Public health initiatives to raise awareness about the importance of eye care are also essential[9]. Therefore, this paper critically examines the current state of eye emergencies in Africa, exploring the causes, consequences, challenges, and potential solutions to improve outcomes in this critical area of health.

This scoping review was conducted to investigate the epidemiology, causes, and management strategies for eye emergencies in Africa, while also identifying barriers to effective treatment. The methodology was carefully designed to ensure a thorough and systematic approach to the selection of literature, extraction of data, and synthesis of findings.

A comprehensive search was performed using the PubMed database to identify studies relevant to ocular emergencies in Africa. The search strategy, summarized in Table 1 below involved using a combination of keywords, including “ocular emergency”, “eye injury”, “Africa” and related terms. The search method utilized Boolean operators and a variety of keywords, including 'ocular emergency', 'eye damage', 'Africa' and associated terms. Search phrases were amalgamated utilizing Boolean operators (e.g., 'AND', 'OR') to optimize the retrieval of pertinent articles. The search was confined to papers published between January 2014 and August 2024 in English, with full-text access. Inclusion criteria specifically targeted research that addressed the epidemiology, etiology, management approaches, and obstacles to the treatment of ocular emergencies in Africa. The search was deliberately limited to studies published between January 2014 and August 2024, ensuring that only the most recent and pertinent literature was considered for inclusion.

| Search component | Keywords/terms used |

| Ocular | “ocular”[All Fields] OR “oculars”[All Fields] |

| Emergency | “emerge”[All Fields] OR “emerged”[All Fields] OR “emergence”[All Fields] OR “emergences”[All Fields] OR “emergencies”[MeSH Terms] OR “emergencies”[All Fields] OR “emergency”[All Fields] OR “emergent”[All Fields] OR “emergently”[All Fields] OR “emergents”[All Fields] OR “emerges”[All Fields] OR “emerging”[All Fields] |

| Africa | “africa”[MeSH Terms] OR “africa”[All Fields] OR “africa s”[All Fields] OR “africas”[All Fields] |

| Date range | 2014: 2024[pdat] |

| Language, full text, relevance | Records filtered to exclude non-English language, no full text, and non-relevant articles. |

The data extraction form comprised fields for study characteristics (author, year, country, design), sample characteristics (size, demographics), types of ocular emergencies, causes, management options, and outcomes. Discrepancies among reviewers during research selection and data extraction were reconciled through consensus or by consulting a third reviewer. This method guaranteed impartiality and uniformity during the evaluation process. The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

The selection of studies was guided by clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria: (1) Studies that specifically focus on ocular emergencies within African countries; (2) Articles published in the English language; (3) Studies that report on the epidemiology, causes, management strategies, and barriers to the treatment of eye emergencies; and (4) Studies with full-text availability.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Studies published prior to 2014; (2) Articles that are not directly relevant to the topic, including those not conducted within the African context; (3) Non-English language studies and studies without accessible full texts; and (4) Editorials, commentaries, and letters were excluded to maintain a focus on original research contributions.

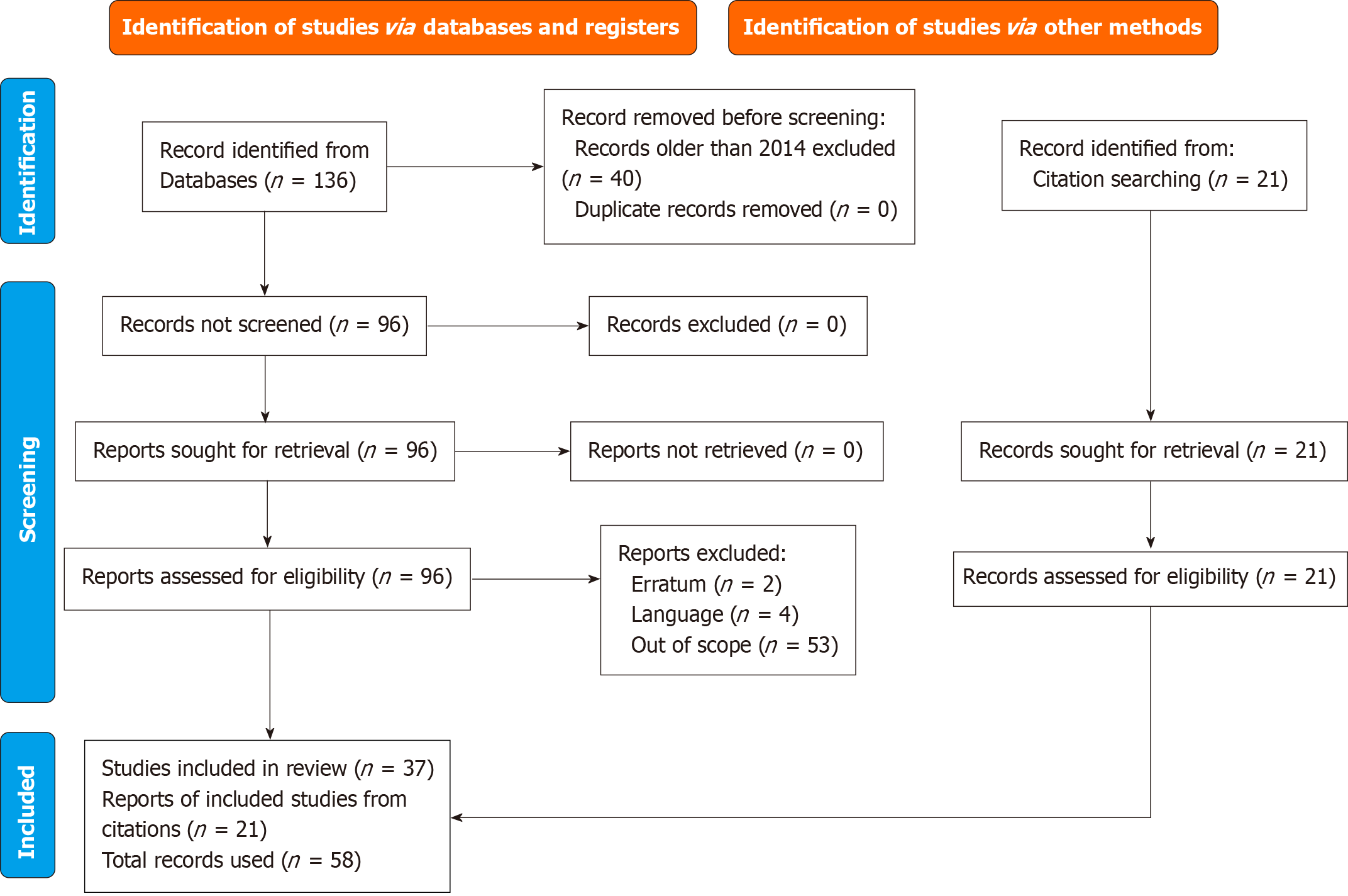

The initial search of the PubMed database yielded 136 records, encompassing a broad range of studies related to ocular emergencies across various African countries. Following this, a multi-stage filtering process was applied to ensure that only the most relevant and high-quality studies were included in the final review.

First, the records were filtered according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, which resulted in the exclusion of studies published before 2014, non-English language articles, and those that did not focus on the African context or eye emergencies. This initial filtering narrowed the list down to 96 records.

The remaining 96 studies were subjected to a rigorous screening process conducted independently by two reviewers. During this phase, the titles and abstracts of each study were meticulously reviewed to assess their relevance to the research objectives. Studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria were retained for full-text review. In cases where there was uncertainty or disagreement between the two reviewers regarding the inclusion of a study, the issue was discussed, and a third reviewer was consulted to reach a consensus. This collaborative approach ensured that the selection process was thorough and unbiased, ultimately leading to a final selection of studies that were deemed highly relevant and aligned with the research objectives. Although full-text availability was a criterion for inclusion to guarantee thorough data extraction, this requirement may have omitted significant studies accessible solely in abstract form.

Data from the selected studies were extracted using a standardized data extraction form. The form captured details such as study characteristics (author, year of publication, country, study design), population characteristics (sample size, demographics), types of eye emergencies reported, causes, management approaches, outcomes, and barriers to treatment. Two reviewers (Bale BI and Idogen OS) independently performed data extraction to ensure accuracy and consistency. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or with the involvement of a third reviewer (Musa M). Given the heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and outcomes reported, a narrative synthesis was conducted. The synthesis focused on summarizing the prevalence and types of eye emergencies, the causes identified, management approaches, and barriers to effective treatment. Findings were grouped by themes related to epidemiology, causes, management strategies, and factors contributing to low treatment rates.

A total of 136 records were extracted using the search algorithm from the PubMed database as shown in Figure 1 below. After limiting the publication spread to 10 years spanning 2014 to 2024, a total of 96 records were obtained. Two authors then rigorously examined each record for relevance, language and completeness. Two records were excluded as they were an erratum to published studies which were also not included while another four were excluded because they were not in the English language. A further 53 records were out of the scope of this paper, and so they were also excluded. The references in 37 studies obtained were examined for relevant records; and a total of 21 relevant studies were further obtained, amounting to the usage of a total of 58 studies in this review.

The factors affecting treatment rates for disease emergencies, such as maternal health and infectious diseases, and those for eye emergencies share common barriers but also exhibit unique challenges. Both categories are significantly hindered by inadequate healthcare infrastructure and a shortage of trained personnel. For instance, in Africa, maternal health and eye emergencies alike are often delayed due to insufficient emergency care services, limited availability of supplies, and long travel times to healthcare facilities in rural areas[10-12]. Additionally, socio-economic factors, such as poverty and cultural norms, play a pivotal role in reducing treatment uptake for both[13]. Gender-specific barriers, including women needing permission from male family members to seek care, exacerbate delays for maternal health emergencies and eye injuries in women[14].

Untreated ocular emergencies pose a significant threat to vision, with global estimates indicating that approximately 2.5 million people are affected by ocular injuries annually[13]. In affluent nations, ocular emergencies are generally addressed via robust healthcare systems featuring sufficient infrastructure, a high concentration of trained professionals, and readily available emergency services. In contrast, resource-constrained environments in Africa encounter substantial obstacles, such as insufficient healthcare facilities, restricted staff capacity, and socio-economic limitations. This significant differential highlights the necessity of resolving these gaps to enhance outcomes for ocular emergencies in Africa.

Men and young individuals represent a significant proportion of those experiencing eye injuries, with one-fifth of adults reported to be affected[14]. In Nigeria, ocular injuries are a significant concern, particularly in Southeastern regions where there is a 3.5% incidence rate of ocular trauma, primarily involving closed globe injuries (76%) caused by blunt objects (57%), affecting mainly young people aged 10 to 19 years[15]. Children are often affected by eye emergencies, with a prevalence rate of 7.93% for eye injuries, commonly presenting as eyelid scars (5.34%), eyebrow scars (2.10%), and canthal scars (0.32%)[16].

Certain professions also face higher risks of eye emergencies due to occupational hazards. For instance, a study by Douglas and Koroye-Egbe[17] found a high prevalence of ocular injuries among welders, with 43.4% experiencing injuries such as burns, foreign bodies, and cuts. Similarly, among carpenters, work-related eye injuries and complaints were reported at rates of 30.7% and 32.5%, respectively, often due to inadequate use of protective eyewear, highlighting a significant occupational health issue[18].

In other parts of West Africa, such as Ghana, the occurrence of ocular injury among cocoa farmers was found to be 11.3 per 1000 worker-years, with lost work time at a rate of 37.3 per 1000 worker-years, indicating a substantial occupational risk for this group[19]. In Côte d'Ivoire, epidemiological data indicates that ocular burns, a form of ocular trauma, constitute 11% of ocular injury cases, with chemical agents being the primary cause in 54% of these incidents[20]. This highlights significant regional risks associated with chemical exposures.

In Southern Africa, particularly in Zimbabwe, there was a high prevalence of open-globe injuries (71.2%) in Zimbabwe with blunt trauma (90%) being the most significant cause[21]. In Northern Cape South Africa, it was reported that 3.2% of acute ocular trauma in which mechanical trauma (blunt, sharp and extraocular foreign body) accounted for over 90% that primarily affect young men (86.3%), with injuries mostly occurring at home (47.9%)[22].

In Ethiopia, ocular trauma predominantly affects males (71.0%) and children (62.87%), with nearly equal prevalence of open globe injuries (47.07%) and closed globe injuries (47.74%). Corneal tears are the most frequent type of injury, accounting for 39.33% of cases[23]. Similarly, in Uganda, eye emergencies are most common among males aged 10 to 20 years, with open globe injuries comprising 72% of cases. The most frequent specific incident is the presence of corneal foreign bodies, occurring in 42% of cases[24].

Other significant eye emergencies in the region include retinal detachment and retinal vessel occlusion. A 2023 prospective study across multiple centers in Nigeria found 237 cases of retinal detachment, with tractional retinal detachment accounting for 25.7% of these cases[25]. Additionally, retinal vascular occlusion was identified in 0.9% of patients in Nigeria[26]. The prevalence of other eye emergencies is listed in Table 2[27-34].

| Ref. | Type of eye emergency (prevalence) | Study period | Sample size | Data sources | Study design | Country in Africa |

| Kyei et al[21] | Open globe injuries (71.2%). Blunt trauma causing open-globe injuries (90%). Penetrating Intraocular, and perforating injuries causing open-globe injuries (10%) | January 2017 to December 2021 (4 years) | 863 | Patients records | Retrospective cross-sectional | Zimbabwe |

| Bert et al[19] | Ocular trauma (25.7%) | 2 days | 556 | Questionnaire and ocular examination | Cross-sectional survey | Ghana |

| Douglas and Koroye-Egbe[17] | Ocular burns (42%). Foreign body injury to the eye (32%). Injuries caused by cuts to the eye (4%) | - | 212 | Ocular examination | Cross-sectional descriptive | Nigeria |

| Onyekwelu et al[18] | Superficial foreign body to the eye (88.6%). Chemical injury (8.6%). Nail injury to the eye (5.7%) | April 7, 2017 to May 15, 2017 (1 month) | 114 | Questionnaire, ocular examination and interview | Descriptive cross-sectional | Nigeria |

| Daoudi et al[27] | Preseptal cellulitis (85%). Orbital cellulitis (15%) | 2008 to 2014 (6 years) | 28 | Patient records | Retrospective cohort | Morocco |

| Ajayi et al[28] | Neovascular glaucoma (0.05%) | January 2015 to December 2019 (4 years) | 566 | Patient records | Retrospective cohort | Nigeria |

| Koki et al[29] | Ocular trauma (16.92%) | January 2008 to December 2014 (6 years) | 591 | Patient records | Retrospective cohort | Cameroon |

| Kibret and Bitew[30] | Fungal keratitis (45.1%) | September 2014 to August 2015 (11 months) | 153 | Clinical examination | Cross-sectional | Ethiopia |

| Haingomalala et al[31] | Serious ocular trauma (5.75%) | January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2011 (2 years) | 1267 | Patient records | Retrospective cohort | Madagascar |

| Damtie and Siraj[32] | Eye injury (7.7%) | 2019 | 300 | Questionnaire | Cross-sectional | Ethiopia |

| Baba et al[33] | Penetrating ocular injury (65.7%) | January 2006 to November 2013 (7 years) | 100 | Patient records | Retrospective cohort | Tunisia |

| Bastola et al[34] | Ocular trauma (1.94%) | September to November 2018 (3 months) | 280 | Clinical examination | Prospective observational | Eritrea |

The epidemiology of ocular emergencies in Africa indicates a significant prevalence among males, younger populations, and individuals employed in hazardous professions. Principal findings reveal considerable disparities in prevalence rates among areas

Accidents are a significant cause of eye emergencies in the African population, often occurring during social activities. Male children, in particular, are at higher risk of ocular trauma during play, with most incidents happening at home and commonly involving closed globe injuries from impacts with various objects such as canes, stones, broomsticks, wood, and fists[35]. A study in Cameroon identified fights as the most frequent cause of ocular trauma, accounting for nearly one-third of all cases, with punches being the predominant mechanism in 21.39% of these cases[36]. In Senegal, physical violence against women also contributes to ocular injuries[37]. Additionally, accidental events such as car crashes and gunshot wounds lead to ocular conditions requiring immediate medical attention[38].

Another form of environmental accident, though rare, is ocular Hymenoptera stings, which are considered an eye emergency due to the severe ocular complications they can cause when the eye is stung or comes into contact with venom from insects of the Hymenoptera order, such as bees, wasps, and ants[39]. Similarly, although rare, snake envenomation, a common public health concern in the savanna regions of West Africa, can cause immediate severe eye damage, inflammation, necrosis, and vision loss if not treated promptly, with potential systemic toxicity and infections necessitating emergency care[40].

Furthermore, ocular infections are a significant cause of eye emergencies, demanding immediate medical intervention to avert severe complications and potential vision loss. Bacteria are one of the causes of most ocular infections such as keratitis, corneal ulcer and endophthalmitis that are ocular emergencies[41]. Several significant factors have been identified as being associated with the prevalence of bacterial ocular infections. These factors include age, farming activities, a history of previous eye surgeries, and poor facial hygiene habits[42]. Similarly, open-globe injuries have been found to potentially result in endophthalmitis[44]. Corneal ulcers also often result from ocular trauma and lead to severe pain, potential corneal scarring, and risk of permanent vision loss if not treated promptly[45]. Moreover, fungal keratitis is one of the most challenging forms of infectious keratitis and is considered an eye emergency[46]. Like corneal ulcer, fungal keratitis can also be caused by ocular trauma[47]. A study by Fekih et al[48] reported that in 78.8% of fungal keratitis cases in Tunisia, fungal filaments were identified as the cause of infection, with Fusarium species being the most frequently isolated, found in 39.4% of the patients, especially those who had experienced ocular trauma. Similarly, parasitic keratitis, particularly caused by Acanthamoeba is another serious, though rare, corneal infection that can lead to emergency ocular injury, particularly among contact lens wearers in rural areas with low hygiene practices[49].

Occupational risks: Occupational hazards constitute a primary source of ocular emergencies, especially among welders, carpenters, and farmers, where insufficient utilization of protective eyewear intensifies the risk

Failure to use protective eyewear and inadequate ocular health and safety training are major contributors to the reported cases of ocular emergencies in Africa[50]. This issue is particularly pronounced among farmers and individuals involved in agricultural activities, who are frequently exposed to hazards such as trauma from farming equipment, contact with vegetable material, eye injuries from animal attacks, and spillage of sand into the eye[50]. While welders in sub-Saharan Africa generally exhibit good ocular protection practices, linked to on-the-job training, work experience, and a history of previous ocular injuries[51], mechanics often suffer from prevalent eye injuries due to not using protective devices, exposing them to hazards such as dust, engine oil, fire sparks, metal crusting, and battery acid[52]. A study in Ethiopia showed that the risk of occupational ocular injuries was seven times higher for workers who did not use protective eyewear and 2.22 times higher for those without health and safety training compared to those who received such training[53]. Furthermore, within work environments involving Africans, the most common ocular injuries included blunt trauma and incidents involving foreign bodies[54].

Healthcare infrastructure, human resources and policy: Government policies are essential in determining how resources are allocated to healthcare infrastructure, directly influencing the availability and quality of care. In African countries, healthcare is delivered across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, each offering varying degrees of service. Primary eye care services are particularly important, as they enable trained mid-level personnel to manage common eye emergencies, thereby reducing the burden on secondary and tertiary hospitals, as noted by Patel et al[6]. However, these primary services are often underdeveloped in many African nations, leaving gaps in early intervention for eye conditions. The lack of critical supplies, such as surgical instruments and medications, further hampers the effectiveness of treatment, as documented by research[55]. In response to these challenges, the World Health Organization (WHO) has made strides by introducing a “Primary Eye Care Training Manual” aimed at equipping healthcare workers with the skills needed to handle common eye emergencies. Furthermore, collaborative efforts between the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness and nursing colleges in East and South Africa have led to the expansion of primary eye care services across 12 additional countries, enhancing access to essential eye care at the primary health care level[56,57].

In addition, sub-Saharan Africa faces a shortage of eye health professionals, including ophthalmologists, optometrists, ophthalmic nurses, and allied personnel, with a particularly uneven distribution, leaving rural areas significantly underserved compared to urban areas[58]. Current challenges include inadequate working conditions (structural issues) and a lack of security prompting trained eye care professionals to work in the city or emigrate internationally[59].

In Africa, the density of ophthalmologists is alarmingly low, with roughly 2.5 ophthalmologists per million indi

Also, although many African countries have developed national eye health plans and fostered collaborations between non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector, there remains a significant disconnect at regional and district levels[60,61]. This lack of local engagement and representation results in insufficient healthcare infrastructure and human resources at the grassroots level, undermining the effectiveness of national strategies[62]. Without the active involvement of local entities in decision-making processes, there is a risk of misaligned priorities and inefficient use of resources, ultimately hampering efforts to improve eye health outcomes and address the needs of communities effectively[63].

People from poorer backgrounds rely on government services for eye care, and when these are not available, affordable and accessible this delays timely care, leading to long-term vision complications[64]. In remote regions, patients often face long travel times to reach adequately equipped facilities, leading to delays in treatment[65]. Moreover, high costs associated with medical consultations, treatments, and surgeries may prevent many individuals from seeking timely care for eye emergencies[66]. Even when services are subsidized, the cost of transportation to healthcare facilities can be prohibitive for low-income families[67].

Cultural and behavioral factors play a significant role in the low treatment rates of eye emergencies in Africa. One such factor is the additional barriers faced by women. In many African societies, women may lack financial autonomy, limiting their ability to pay for medical services[68]. Furthermore, cultural norms often require women to obtain permission from male family members before seeking medical care, which can delay or prevent access to timely treatment for eye emergencies[69]. These gender-specific barriers compound the overall challenges in accessing healthcare, contributing to the high prevalence of untreated eye conditions and resulting in greater risk of severe vision loss and other complications[70].

Individual impact: A person’s ability to carry out daily tasks is significantly impaired by vision loss, which results in a loss of independence[71]. Simple tasks such as reading, driving, and face recognition become challenging, drastically reducing the quality of life[72]. Untreated eye emergencies can have serious consequences on a person’s quality of life that can be severe and permanent[73]. Some of these emergencies include acute glaucoma, retinal detachment, severe eye infections, and traumatic eye injuries[74].

In Sub-Saharan Africa, trauma-induced orbito-oculoplastics diseases, if untreated, significantly harm individuals' psycho-social well-being, economic stability, educational achievements, quality of life, and pose a substantial threat to vision[75]. In cases of traumatic cataract it can lead to partial or total loss of vision[76]. Additionally, ocular trauma can result in the development of superficial corneal scars, which significantly impair vision by causing visual blur, glare, and reduced visual acuity, thereby affecting daily activities and overall quality of life[77].

In addition, untreated eye emergencies may result in persistent pain and discomfort. Acute angle-closure glaucoma, an eye emergency, is linked to excruciating eye discomfort and nausea[78]. Moreover, untreated infections can cause chronic inflammation and possibly spread to other body regions[79]. Untreated ocular syphilis, particularly prevalent among HIV-positive individuals, can cause severe eye conditions such as uveitis, retinitis, optic neuritis, and panuveitis, leading to sudden vision loss if not promptly addressed[80]. Psychological discomfort is frequently present alongside these physical symptoms. Anxiety and sadness might result from the pain and discomfort as well as the fear of permanent vision loss[81,82].

Public health and economic impact: On a larger scale, untreated eye emergencies represent a significant public health concern[83]. Ocular injury is a significant public health concern, particularly in low-resource cultures, as it is a primary cause of ocular morbidity and unilateral vision impairment[84]. Vision impairment and blindness substantially burden healthcare systems, increasing the need for specialized care, prolonged treatment, and potential complications, increasing the demand for healthcare professionals and facilities[85,86]. Individuals with untreated eye conditions often require more frequent medical visits and interventions, which puts additional strain on already limited healthcare resources, especially in low-income and underserved areas[87].

Vision impairment reduces workforce participation and productivity, impacting national economies[88]. Individuals who suffer from vision loss may find themselves unemployed or unable to make as much money. Good vision is necessary for many occupations, thus persons who lose their vision might face career limitations[89]. In addition to impacting the individual, this loss of income strains their families financially and makes them more dependent on welfare assistance[90].

In many regions of Africa, healthcare systems face numerous challenges, including limited resources, infrastructure, and access to specialized medical care. Access to treatment for eye emergencies varies significantly, with some ophthalmological services available, particularly in urban areas.

Over the past decade (2014–2024), trends in eye emergencies have shown significant strides in certain areas alongside persistent challenges. Awareness campaigns, particularly in urban centers, have improved due to enhanced public health initiatives and collaborations with NGOs, leading to greater recognition of eye health issues[91]. Urban areas have seen better access to basic care and advanced treatments, as highlighted by the establishment of primary eye care facilities and integration into primary health care systems in some African regions. However, rural areas still face barriers contributing to delayed treatment and higher rates of preventable blindness.

Surgical procedures, including corneal transplants and cataract surgeries, are essential in mitigating impaired vision resulting from ocular crises. Enhancing accessibility to these procedures, especially in rural regions, is crucial for alleviating the impact of vision impairment. Corneal transplantation is a surgical procedure that generally yields positive results. Unfortunately, in regions where subspecialty treatments like corneal transplants are not readily available, patients can develop serious complications which may result in blindness. A study in Malawi revealed that while many ocular trauma patients did not require surgical intervention, about one-third needed procedures such as corneal repair and cataract surgery[92]. Also, in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo, the management of ocular foreign bodies included either straightforward removal or removal with suturing for deeper foreign bodies, which successfully preserved visual acuity in the majority of patients[93].

In Lagos, Nigeria, a study found that ocular trauma was the most common indication for destructive eye surgeries, with evisceration being frequently performed due to trauma or infection, highlighting the significant impact of ocular trauma and the urgent need for advanced surgical options to prevent severe outcomes[94]. For the management of ocular or peri-ocular trauma, the majority of patients requiring urgent surgery to the peri-ocular region, the treatment landscape in South Africa involves a high demand for immediate and multi-disciplinary surgical care, encompassing specialties like ophthalmology, maxillofacial, plastic, otorhinolaryngology, and neurosurgery[95,96]. This underscores the complexity of the injuries, highlights the extensive nature of trauma and the necessity for a coordinated and comprehensive approach to treatment (such as orthopedic operations, laparotomies, and vascular procedures).

Furthermore, due to the unavailability of some technological diagnostic testing in Africa, it may delay access to treatment of eye emergencies that can result in visual impairment or even blindness. A study by Miller et al[97] found that African ophthalmologists specialized in ophthalmic trauma adopt a more conservative approach to managing open globe injuries, using computed tomography (CT) imaging selectively for specific indications like suspected intraocular foreign bodies, unlike their counterparts in North and South America who routinely obtain CT imaging for all suspected cases. In Liberia, the lack of magnetic resonance imaging in a resource-limited setting necessitated the use of CT scans (coronal and sagittal cuts with variable window width) to detect intra-orbital wooden foreign bodies, facilitating their surgical removal to relieve pain, treat infection, and prevent complications[98]. This suggests that there may be fewer resources, such as availability of advanced imaging equipment, which can impact the thoroughness and immediacy of the diagnosis and treatment. This can potentially lead to differences in outcomes and quality of care for patients with eye emergencies in Africa. One such occurrence was reported in a case of retrobulbar hematoma reported in Uganda. Retrobulbar hematoma, an uncommon emergency that can cause blindness, requires prompt surgical intervention and may be delayed due to unavailability of radiological evaluation, particularly in rural areas where patients often present late and lack access to radiological services, thereby necessitating emergency surgical decompression of the orbit[99].

Certain ocular infections are considered eye emergencies and require immediate medical attention to prevent complications and preserve vision. In the case of ocular infections like endophthalmitis and bacterial keratitis, prompt and intensive treatment with topical antibiotics is crucial[100]. Despite this, according to some studies conducted in South Africa, there is still inadequate scientific evidence to support the effectiveness and safety of adjunctive steroid use (systemic or topical) compared to antibiotics alone in the treatment of these conditions[101,102]. Unlike fungal keratitis, which commonly occurs among people living in rural communities and often has worse outcomes than bacterial keratitis, its early management with drug-based medical treatments has achieved good outcomes in Egypt despite the shortage of medical resources[103].

Chemical injuries due to toxins and other harmful substances are significant causes of eye emergencies, requiring prompt and effective management to prevent long-term damage and vision loss. Venom ophthalmia, resulting from ocular contact with snake venom from various species of spitting cobras in Africa, is a severe ocular chemical injury that necessitates immediate medical attention, including thorough irrigation, analgesics, antibiotics, antihistamines, and anti-inflammatory topical drugs[104]. Similar to a reported case of venom ophthalmia in South Africa, the initial management involves extensive irrigation, followed by the application of topical cycloplegics and antibiotics to prevent secondary infection, without requiring topical steroids or antivenom (topical or intravenous)[105].

Optic neuritis, however, less commonly documented than other causes, constitutes a significant etiology of ocular emergencies in Africa. The prevalence may be undervalued due to restricted diagnostic skills. Timely diagnosis and intervention are essential to avert permanent vision impairment.

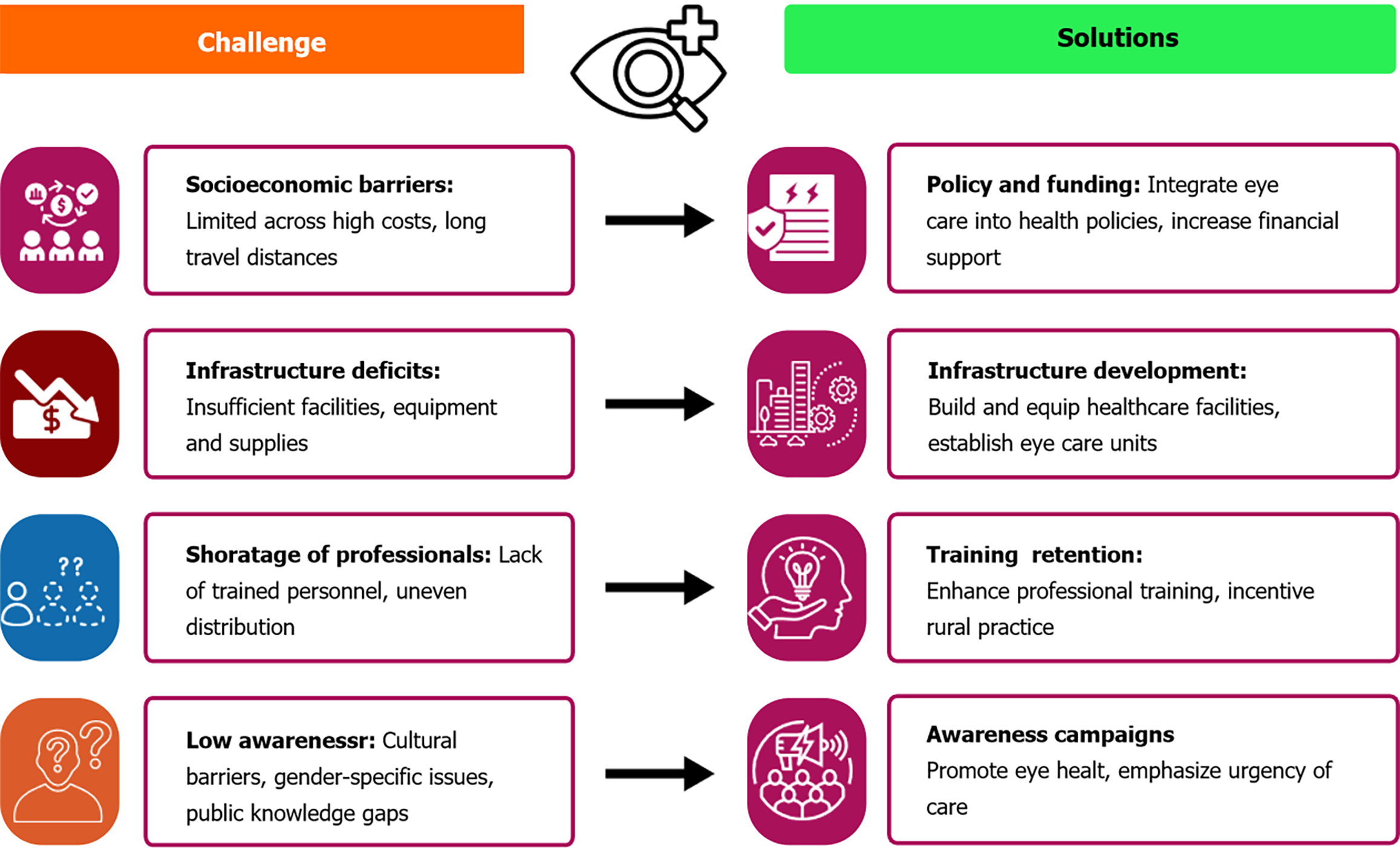

Resource limitations: Despite a strong commitment to managing eye emergencies effectively, African countries frequently encounter significant challenges due to limited financial and technical resources[106,107]. These constraints are a major impediment to the provision of high-quality eye care and the timely treatment of eye emergencies. Figure 2 summarizes the challenges and most appropriate solutions.

The financial constraints faced by many African countries significantly impact their ability to manage eye emergencies. Health budgets are often limited and must be stretched to cover a wide range of medical needs, leaving insufficient funds for eye care[108,109]. Eye care services, including routine examinations, emergency treatments, and surgical inter

In addition to financial constraints, African countries face significant technical challenges in managing eye emergencies. There is a critical shortage of trained ophthalmologists, optometrists, and other eye care professionals[113]. For instance, in Nigeria, the availability and regional distribution of oculoplastic surgical services are inadequate, largely due to insufficient training[114]. In addition, the training and retention of these specialists are hampered by inadequate educational facilities and opportunities for professional development[115]. Consequently, the few available specialists are often concentrated in urban centers, leaving rural areas underserved[116].

Logistical challenges are a significant barrier to effective interventions for eye emergencies in Africa. One of the primary logistical issues is the scarcity of transportation funds, which can delay or completely hinder patients from accessing medical facilities for necessary interventions[117]. In addition, the distribution of eye care facilities is uneven, with most specialized centers situated in urban areas[118]. This urban-rural disparity contributes to the challenges of accessing eye care services in rural regions and people would often have to travel long distances to reach specialized eye care centers[119]. This can be particularly challenging for elderly patients, those with disabilities, and families with limited financial means.

Awareness and knowledge regarding eye health issues are essential for the timely treatment of eye emergencies. When individuals are unaware of their conditions, they are less likely to seek appropriate care[120]. Furthermore, the sources from which patients obtain information about their conditions can impact their response to emergency eye cases[121]. This is such that even when individuals actively seek information, they may encounter a lack of reliable sources for accurate details about their eye conditions. For instance, a study in South Africa found that limited education on eye issues and the necessity for regular eye screenings among patients in a diabetic outpatient clinic affected their diagnosis and treatment[122].

Awareness of the importance of adhering to treatment plans is crucial for achieving effective medical outcomes[123]. This is significantly true for eye emergency cases. This lack of awareness can lead to poor compliance[124], as patients who do not perceive the benefits of following recommended care may neglect or discontinue it altogether. Similarly, unawareness of available facilities for managing eye emergencies can cause patients to seek alternative, and often less effective, treatments[125].

The demographic and geographic traits of the study population may restrict the applicability of the findings to wider populations." Although our results offer significant insights into low treatment rates of eye emergencies in Africa, one must exercise caution when generalizing these findings to communities with differing demographic, socioeconomic, or healthcare circumstances. This study's findings, especially within the African setting, highlight the necessity of customizing interventions to local conditions while evaluating their possible relevance to other worldwide locations.

Community engagement and education: Effective community engagement and education are essential components in addressing the low treatment rates of eye emergencies in Africa. Preventive strategies should prioritize promoting and teaching the use of eye protective gear, particularly for individuals involved in high-risk activities such as operating machinery, agriculture and participating in certain sports[126]. Educational campaigns can highlight the importance of protective eyewear in preventing eye injuries and related emergencies, thus reducing the incidence of such cases.

Moreover, there is a crucial need to emphasize the importance of seeking prompt medical attention in the event of eye emergencies[127]. Public health initiatives should focus on raising awareness about the symptoms and dangers of delayed treatment for eye injuries and infections[128]. By educating communities about the urgency of timely medical intervention, it is possible to mitigate the risk of severe complications and improve overall eye health outcomes[129].

To address the difficulties of ocular emergencies in Africa, it is imperative to implement people-centered eye care systems. These encompass community-oriented screening initiatives, the incorporation of ocular health into primary healthcare services, and the formation of referral networks to enhance access to specialized care. Furthermore, comprehensive monitoring frameworks, including real-time surveillance systems for ocular crises, can facilitate targeted treatments and resource distribution.

To address the low treatment rate of eye emergencies in Africa, enhancing healthcare infrastructure is paramount. This involves substantial investment in the construction and refurbishment of healthcare facilities for emergency care services[130]. Upgrading existing hospitals and clinics with state-of-the-art ophthalmic equipment and ensuring a steady supply of essential medical materials are crucial steps[131]. Furthermore, establishing specialized eye care units within these facilities can significantly improve the accessibility and quality of emergency eye care[132]. Ensuring that these infrastructures are evenly distributed across rural and urban areas will help bridge the gap in eye care services and provide timely treatment to those in need[133].

Training and retaining more eye care professionals, such as ophthalmologists, optometrists, and nurses, are also critical for improving the treatment rates of eye emergencies especially in rural areas[134,135]. Investment in professional development and continuing education programs can provide the necessary skills to manage eye emergencies effectively[136]. Furthermore, creating a robust referral system to ensure that patients can access specialized care promptly can significantly enhance the management of eye emergencies[137].

Partnerships with NGOs and the private sector can also play a crucial role in bridging resource gaps. Ensuring that local organizations are actively involved in planning and resource allocation can help bridge the gap between national strategies and grassroots needs[137]. The Gambia’s model exemplifies how effective partnerships and health system frameworks can address vision care challenges and serves as a potential blueprint for other African countries seeking to enhance their vision care systems[138]. Therefore, not only empowering local organizations but also integrating them into the decision-making processes can ensure that resources are used effectively and that services are aligned with community needs[139].

The WHO's data indicating a reduction in vision loss in the African Region is a positive advancement. This trend illustrates the effects of enhanced healthcare delivery, heightened awareness, and focused efforts like the WHO's Vision 2020 campaign[57]. Yet, awareness of eye care is insufficient in numerous areas of the African Region, with misunderstandings regarding the urgency of ocular emergencies leading to procrastination in obtaining treatment. Augmenting financial support for eye care initiatives is warranted due to the considerable burden of avoidable visual impairment and its socioeconomic repercussions. Targeted expenditures in eye care do not exclude financing for other diseases but rather address a significant deficiency in healthcare services.

Comprehensive health policies and advocacy are vital for improving healthcare across Africa[140]. Developing standardized frameworks and guiding principles will help countries better incorporate ocular health into their healthcare systems[141]. Especially in the area of financial integration, these policies should be thorough, including budgets, plans, and guidelines to tackle the issue of inadequate eye care treatment in the region[142]. Integrating comprehensive eye care into Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is also vital for improving public health outcomes and ensuring equitable access to vision care[143]. However, many UHC programs currently lack comprehensive coverage for eye health care, resulting in significant out-of-pocket expenses and limited access to specialized care, such as in eye emergencies[144]. Innovative financing mechanisms, such as health insurance schemes and community health funds, can also be explored as has been done in Ghana and South Africa[145,146]. This approach will promote equitable access to eye care services and improve overall health outcomes[137]. Therefore, the challenges and solutions to eye emergencies in Africa are summarized in Figure 2 below.

The drawback of this study lies in the possibility of residual confounding, as not all variables that potentially affect the observed relationships may have been evaluated or considered. Lifestyle factors or genetic predispositions, which were outside the purview of this investigation, may have influenced the outcomes. Subsequent study should endeavor to incorporate a broader array of variables to mitigate this constraint.

Also, the dependence on self-reported and secondary data for certain variables creates the potential for recall and misclassification biases. Recall bias may arise if people wrongly recollect past events, whereas misclassification bias could stem from inaccuracies in data entry or categorization. These biases may compromise the validity of the findings. We therefore suggest utilizing objective metrics or primary data acquisition may alleviate these constraints.

While the longitudinal design of this study offers a more robust foundation for inferring temporal relationships than cross-sectional studies, it does not definitively establish causality. Unmeasured variables and other biases intrinsic to observational studies may continue to affect the outcomes. Consequently, prudence is necessary in interpreting the data as causal, and experimental research is required to validate these connections.

This study discusses the critical and under-addressed issue of low treatment rates for eye emergencies in Africa, which significantly contributes to the high prevalence of preventable blindness across the continent. Eye emergencies require immediate medical attention to prevent severe outcomes, such as permanent vision loss. However, the ability to respond effectively to these emergencies is severely constrained by several factors unique to Africa. Socioeconomic barriers, particularly in rural regions, impede access to healthcare facilities equipped to handle ocular emergencies. The continent faces a significant shortage of trained eye care professionals, compounded by the uneven distribution of available specialists between the rural and urban regions, which further limits access to timely care. The epidemiology of eye emergencies in Africa reveals a worrying trend of increasing incidence, with young individuals, men, and those in high-risk occupations disproportionately affected. This study also notes that untreated eye emergencies can have devastating personal consequences, including a drastic reduction in quality of life, loss of independence, and long-term economic impacts. The challenges in managing these emergencies are exacerbated by inadequate healthcare infrastructure, lack of essential supplies, and insufficient training for healthcare workers at the primary care level. Our findings corroborate existing literature that underscores the significant deficiency of eye care experts in Africa and its effect on emergency care provision. This study emphasizes the necessity for policies that promote workforce development, encompassing the training and retention of eye care workers. The results underscore the necessity of incorporating eye care into primary healthcare systems to improve accessibility. These results ought to guide national health programs and international partnerships focused on mitigating preventable eyesight loss

Effective initiatives to enhance eye emergency care in Africa encompass the establishment of mobile eye clinics for remote populations, the incorporation of eye care within existing primary healthcare systems, and the implementation of specialized training programs for primary healthcare practitioners. Public awareness efforts, customized to local contexts, should be executed to inform populations about the significance of prompt medical attention for ocular emergencies. These programs necessitate collaborative efforts among governments, NGOs, and international organizations to guarantee sustainability and efficacy. This study calls for urgent action to address the low treatment rates of eye emergencies in Africa. This includes enhancing healthcare infrastructure, especially in rural areas, and improving the training and retention of eye care professionals. It also advocates for stronger community engagement and education to raise awareness about the importance of eye care and the need for timely medical intervention. Furthermore, the study emphasizes the necessity of policy reforms and increased funding to ensure that eye health is integrated into broader public health strategies and that resources are allocated effectively to prevent avoidable vision loss across the continent.

| 1. | Jairath N, Commiskey P, Kaplan A, Paulus YM. FLASH: A Novel Tool to Identify Vision-Threating Eye Emergencies. Int J Ophthalmic Res. 2020;6:336-343. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Murray D. Emergency management: angle-closure glaucoma. Community Eye Health. 2018;31:64. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Oluyemi F. Epidemiology of penetrating eye injury in ibadan: a 10-year hospital-based review. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2011;18:159-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kayoma DH, Oronsaye DA. Management of painful blind eye in Africa: A review. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2024;14:245-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Babalola OE. The peculiar challenges of blindness prevention in Nigeria: a review article. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2011;40:309-319. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Patel D, Gilbert S. Investment in human resources improves eye health for all. Community Eye Health. 2018;31:37-39. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Jones I. Delivering universal eye health coverage: a call for more and better eye health funding. Int Health. 2022;14:i6-i8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aborode AT, Hasan MM, Jain S, Okereke M, Adedeji OJ, Karra-Aly A, Fasawe AS. Impact of poor disease surveillance system on COVID-19 response in africa: Time to rethink and rebuilt. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;12:100841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xulu-Kasaba Z, Mashige K, Naidoo K. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Eye Health among Public Sector Eye Health Workers in South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Page MJ, Moher D, Brennan S, McKenzie JE. The PRISMATIC project: protocol for a research programme on novel methods to improve reporting and peer review of systematic reviews of health evidence. Syst Rev. 2023;12:196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Parmar UPS, Surico PL, Singh RB, Romano F, Salati C, Spadea L, Musa M, Gagliano C, Mori T, Zeppieri M. Artificial Intelligence (AI) for Early Diagnosis of Retinal Diseases. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dotse-Gborgbortsi W, Tatem AJ, Matthews Z, Alegana VA, Ofosu A, Wright JA. Quality of maternal healthcare and travel time influence birthing service utilisation in Ghanaian health facilities: a geographical analysis of routine health data. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e066792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Opara UC, Iheanacho PN, Li H, Petrucka P. Facilitating and limiting factors of cultural norms influencing use of maternal health services in primary health care facilities in Kogi State, Nigeria; a focused ethnographic research on Igala women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024;24:555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Greenspan JA, Chebet JJ, Mpembeni R, Mosha I, Mpunga M, Winch PJ, Killewo J, Baqui AH, McMahon SA. Men's roles in care seeking for maternal and newborn health: a qualitative study applying the three delays model to male involvement in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jac-Okereke CC, Jac-Okereke CA, Ezegwui IR, Umeh RE. Current pattern of ocular trauma as seen in tertiary institutions in south-eastern Nigeria. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21:420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Okpala NE, Umeh RE, Onwasigwe EN. Eye Injuries Among Primary School Children in Enugu, Nigeria: Rural vs Urban. Ophthalmol Eye Dis. 2015;7:13-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Douglas KE, Koroye-Egbe A. Prevalence of Ocular Injuries among Welders in Yenagoa, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Nig Hosp Pract. 2018;21:179044. |

| 18. | Onyekwelu OM, Aribaba OT, Musa KO, Idowu OO, Salami MO, Odiaka YN. Ocular morbidity and utilisation of protective eyewear among carpenters in Mushin local government, Lagos, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2019;26:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bert BK, Rekha H, Percy MK. Ocular injuries and eye care seeking patterns following injuries among cocoa farmers in Ghana. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16:255-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ko Man CE, Konan Manmi SMP, Agbohoun RP, Kouassi-Rebours C, Sowagnon YTC, N'da HC, Kouadio Kouao CR, N'guessan LC, Kouassi FX. [Ocular burns: epidemiological, clinical, therapeutic and evolutionary aspects at the Cocody University Hospital, Côte d'Ivoire]. Med Trop Sante Int. 2024;4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kyei S, Kwarteng MA, Asare FA, Jemitara M, Mtuwa CN. Ocular trauma among patients attending a tertiary teaching hospital in Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0292392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Stuart KV, Dold C, van der Westhuizen DP, de Vasconcelos S. The epidemiology of ocular trauma in the Northern Cape, South Africa. African Vision and Eye Health. 2022;81. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Alem KD, Arega DD, Weldegiorgis ST, Agaje BG, Tigneh EG. Profile of ocular trauma in patients presenting to the department of ophthalmology at Hawassa University: Retrospective study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mudondo M, Kitanda J. Prevalence, incidence and management practices of ophthalmic emergencies, A cross-sectional study in Jinja district referral hospitals. SJ-Ophthalmology. 2024;1:11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Nkanga DG, Agweye CT, Okonkwo ON, Ovienria W, Adenuga O, Akanbi T, Udoh ME, Oyekunle I, Ibanga AA; Collaborative Retina Research Network (CRRN), Study Report 1. Tractional Retinal Detachment: Prevalence and Causes in Nigerians. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2023;13:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Okonkwo ON, Adenuga OO, Nkanga D, Ovienria W, Ibanga A, Agweye CT, Oyekunle I, Akanbi T; Collaborative Retina Research Network Report II. Prevalence and systemic associations of retinal vascular occlusions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ann Afr Med. 2023;22:279-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Daoudi A, Ajdakar S, Rada N, Draiss G, Hajji I, Bouskraoui M. [Orbital and periorbital cellulitis in children. Epidemiological, clinical, therapeutic aspects and course]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2016;39:609-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ajayi I, Omotoye O, Ajite K, Abah E. Presentation, etiology and treatment outcome of neovascular glaucoma in Ekiti state, South Western Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21:1266-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Koki G, Helles G, Bilong Y, Biangoup P, Aboubakar H, Epée E, Bella AL, Ebana Mvogo C. [Characteristics of post-traumatic blindness at the Yaoundé Army Training, Application and Referral Hospital]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2018;41:540-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kibret T, Bitew A. Fungal keratitis in patients with corneal ulcer attending Minilik II Memorial Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Haingomalala Z, Randrianarisoa HL, Volamarina RF, Raobela L, Bernardin P, Andriantsoa V. [Serious ocular trauma in children: Retrospective study of 74 cases]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2016;39:e81-e82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Damtie D, Siraj A. The Prevalence of Occupational Injuries and Associated Risk Factors among Workers in Bahir Dar Textile Share Company, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health. 2020;2020:2875297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Baba A, Zbiba W, Korbi M, Mrabet A. [Epidemiology of open globe injuries in the Tunisian region of Cap Bon: Retrospective study of 100 cases]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2015;38:403-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bastola P, Ibrahim A, Michael D, Misghna H, Russom R, Polina Dahal, Ibrahim F. Patterns of ocular trauma and visual acuity outcomes in patients attending the National Eye Referral Hospital of Eritrea. JCMC. 2021;11:80-87. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Ugalahi MO, Adebusoye SO, Olusanya BA, Baiyeroju A. Ocular injuries in a paediatric population at a child eye health tertiary facility, Ibadan, Nigeria. Injury. 2023;54:917-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Koki G, Epée E, Omgbwa Eballe A, Ntyame E, Mbogos Nsoh C, Bella AL, Ebana Mvogo C. Ocular trauma in an urban Cameroonian setting: A study of 332 cases evaluated according to the Ocular Trauma Score. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2015;38:735-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Leye MMM, Ndiaye P, Ndiaye D, Seck I, Faye A, Tal Dia A. [Epidemiological, clinical and forensic physical violence against women in Tambacounda (Senegal)]. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2017;65:189-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Murray AD. An Approach to Some Aspects of Strabismus from Ocular and Orbital Trauma. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22:312-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rouatbi A, Chebbi A, Bouguila H. Hymenoptera insect stings: Ocular manifestations and management. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2019;42:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Katibi OS, Adepoju FG, Olorunsola BO, Ernest SK, Monsudi KF. Blindness and scalp haematoma in a child following a snakebite. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:1041-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Watson S, Cabrera-Aguas M, Khoo P. Common eye infections. Aust Prescr. 2018;41:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Teweldemedhin M, Saravanan M, Gebreyesus A, Gebreegziabiher D. Ocular bacterial infections at Quiha Ophthalmic Hospital, Northern Ethiopia: an evaluation according to the risk factors and the antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial isolates. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Haile Z, Mengist HM, Dilnessa T. Bacterial isolates, their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern, and associated factors of external ocular infections among patients attending eye clinic at Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0277230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Du Toit N, Mustak S, Cook C. Randomised controlled trial of prophylactic antibiotic treatment for the prevention of endophthalmitis after open globe injury at Groote Schuur Hospital. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101:862-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Abubakar UM, Lawan A, Muhammad I. Clinical pattern and antibiotic sensitivity of bacterial corneal ulcers in Kano, Northern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2018;17:151-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Bisen AC, Sanap SN, Agrawal S, Biswas A, Mishra A, Verma SK, Singh V, Bhatta RS. Etiopathology, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Fungal Keratitis. ACS Infect Dis. 2024;10:2356-2380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Zbiba W, Baba A, Bouayed E, Abdessalem N, Daldoul A. A 5-year retrospective review of fungal keratitis in the region of Cap Bon. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2016;39:843-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Fekih O, Haj Said O, Zgolli HM, Mabrouk S, Bakir K, Nacef L. Microbiologic profile of the mycosic absess on a reference center in Tunisia. Tunis Med. 2019;97:644-649. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Zbiba W, Abdesslem NB. Acanthamoeba keratitis: An emerging disease among microbial keratitis in the Cap Bon region of Tunisia. Exp Parasitol. 2018;192:42-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Boadi-Kusi SB, Hansraj R, Mashige KP, Ilechie AA. Factors associated with protective eyewear use among cocoa farmers in Ghana. Inj Prev. 2016;22:365-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Atalay YA, Gebeyehu NA, Gelaw KA. Systematic review and meta-analysis on prevalence, pattern, and factors associated with ocular protection practices among welders in sub-Saharan Africa. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1397578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Abu EK, Boadi-Kusi SB, Opuni PQ, Kyei S, Owusu-Ansah A, Darko-Takyi C. Ocular Health and Safety Assessment among Mechanics of the Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2016;11:78-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Mengistu HG, Alemu DS, Alimaw YA, Yibekal BT. Prevalence of Occupational Ocular Injury and Associated Factors Among Small-Scale Industry Workers in Gondar Town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2021;13:167-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Schwartz R, Goldstein M, Loewenstein A, Barak A. [Presentation of ocular problems among displaced persons from Sudan and Eritrea at the Tel Aviv medical center]. Harefuah. 2017;156:19-21. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Hsia RY, Mbembati NA, Macfarlane S, Kruk ME. Access to emergency and surgical care in sub-Saharan Africa: the infrastructure gap. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:234-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Nyabera K. Strengthening Eye Health in ECSA: Integrating Primary Eye Care into Primary Health Care. 2024. Available from: https://www.iapb.org/blog/strengthening-eye-health-in-ecsa-integrating-primary-eye-care-into-primary-health-care. |

| 57. | World Health Organization. Primary Eye Care training manual. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/primary-eye-care-training-manual. |

| 58. | LeBrun DG, Chackungal S, Chao TE, Knowlton LM, Linden AF, Notrica MR, Solis CV, McQueen KA. Prioritizing essential surgery and safe anesthesia for the Post-2015 Development Agenda: operative capacities of 78 district hospitals in 7 low- and middle-income countries. Surgery. 2014;155:365-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Sharma D, Cotton M. Overcoming the barriers between resource constraints and healthcare quality. Trop Doct. 2023;53:341-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Sukati VN, Moodley VR, Mashige KP. A situational analysis of eye care services in Swaziland. J Public Health Afr. 2018;9:892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Jolley E, Mafwiri M, Hunter J, Schmidt E. Integration of eye health into primary care services in Tanzania: a qualitative investigation of experiences in two districts. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Azevedo MJ. The State of Health System(s) in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. In: Historical Perspectives on the State of Health and Health Systems in Africa, Volume II. African Histories and Modernities. African Histories and Modernities. New York, United States: Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2017. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Buthelezi LM, van Staden D. Integrating eye health into policy: Evidence for health systems strengthening in KwaZulu-Natal. Afr Vision Eye Health. 2020;79. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Ntsoane MD, Oduntan OA. A review of factors influencing the utilization of eye care services. Afr Vision Eye Health. 2010;69. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Arunga S, Kintoki GM, Gichuhi S, Onyango J, Newton R, Leck A, Macleod D, Hu VH, Burton MJ. Delay Along the Care Seeking Journey of Patients with Microbial Keratitis in Uganda. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2019;26:311-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Alrasheed SH. A systemic review of barriers to accessing paediatric eye care services in African countries. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21:1887-1897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Gai MJ, Reddy V, Xu V, Noori NH, Demory Beckler M. Illuminating Perspectives: Navigating Eye Care Access in Sub-Saharan Africa Through the Social Determinants of Health. Cureus. 2024;16:e61841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Idris IB, Hamis AA, Bukhori ABM, Hoong DCC, Yusop H, Shaharuddin MA, Fauzi NAFA, Kandayah T. Women's autonomy in healthcare decision making: a systematic review. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23:643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Rono MMed HK, Macleod D, Bastawrous A, Wanjala E, Gichangi M, Burton MJ. Utilization of Secondary Eye Care Services in Western Kenya. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Omar F, McCluskey K, Mashayo E, Yong AC, Mulewa D, Graham C, Price-Sanchez C, Othman O, Graham R, Chan VF. Needs and views on eye health and women's empowerment and theory of change map: implication on the development of a women-targeted eyecare programme for older Zanzibari craftswomen. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2024;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Stevenson MR, Hart PM, Montgomery AM, McCulloch DW, Chakravarthy U. Reduced vision in older adults with age related macular degeneration interferes with ability to care for self and impairs role as carer. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1125-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Jammal HM, Khader Y, Kanaan SF, Al-Dwairi R, Mohidat H, Al-Omari R, Alqudah N, Saleh OA, Alshorman H, Al Bdour M. The Effect of Visual Impairment and Its Severity on Vision-Related and Health-Related Quality of Life in Jordan: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:3043-3056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Finger RP, Fenwick E, Marella M, Dirani M, Holz FG, Chiang PP, Lamoureux EL. The impact of vision impairment on vision-specific quality of life in Germany. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3613-3619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Emrani E, Haritoglou C. Ocular emergencies. MMW Fortschr Med. 2019;161:60-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Balogun BG, Adekoya BJ, Balogun MM, Ehikhamen OA. Orbito-oculoplastic diseases in lagos: a 4-year prospective study. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21:236-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Saa KB, Maneh N, Vonor K, Banla M, Sounouvou I, Alaglo K, Balo KP. Management and functional results of traumatic cataract in the central region of Togo. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Maghsoudlou P, Sood G, Gurnani B, Akhondi H. Cornea Transplantation. 2024 Feb 24. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Kahraman N, Durmaz O, Durna MM. Mirtazapine-induced acute angle closure. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63:539-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Teweldemedhin M, Gebreyesus H, Atsbaha AH, Asgedom SW, Saravanan M. Bacterial profile of ocular infections: a systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17:212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Mathew D, Smit D. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of ocular syphilis and neurosyphilis among individuals with and without HIV infection. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105:70-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Virgili G, Parravano M, Petri D, Maurutto E, Menchini F, Lanzetta P, Varano M, Mariotti SP, Cherubini A, Lucenteforte E. The Association between Vision Impairment and Depression: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies. J Clin Med. 2022;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Binder KW, Wrzesińska MA, Kocur J. Anxiety in persons with visual impairment. Psychiatr Pol. 2020;54:279-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Ezinne NE, Shittu O, Ekemiri KK, Kwarteng MA, Tagoh S, Ogbonna G, Mashige KP. Visual Impairment and Blindness among Patients at Nigeria Army Eye Centre, Bonny Cantonment Lagos, Nigeria. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Abu EK, Ocansey S, Gyamfi JA, Ntodie M, Morny EK. Epidemiology and visual outcomes of ocular injuries in a low resource country. Afr Health Sci. 2020;20:779-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Soboka JG, Teshome TT, Salamanca O, Calise A. Evaluating eye health care services progress towards VISION 2020 goals in Gurage Zone, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Jeon B, Koo H, Choi HK, Han E. The Impact of Visual Impairment on Healthcare Use among Four Medical Institution Types: A Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2023;64:455-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Hashemi H, Yekta A, Jafarzadehpur E, Doostdar A, Ostadimoghaddam H, Khabazkhoob M. The prevalence of visual impairment and blindness in underserved rural areas: a crucial issue for future. Eye (Lond). 2017;31:1221-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Frick KD, Foster A. The magnitude and cost of global blindness: an increasing problem that can be alleviated. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:471-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Chakravarthy U, Biundo E, Saka RO, Fasser C, Bourne R, Little JA. The Economic Impact of Blindness in Europe. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017;24:239-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Varma R, Wu J, Chong K, Azen SP, Hays RD; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Impact of severity and bilaterality of visual impairment on health-related quality of life. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1846-1853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Kiva Z, Wolvaardt JE. Assessing awareness and treatment knowledge of preventable blindness in rural and urban South African communities. S Afr Med J. 2024;114:e1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Zungu T, Mdala S, Manda C, Twabi HS, Kayange P. Characteristics and visual outcome of ocular trauma patients at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Malawi. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Maloba V, Nday F, Mwamba B, Tambwe H, Senda F, Ktanga L, Borasisi G. [Ocular foreign bodies: Epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects in Lubumbashi: About 98 cases]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2020;43:704-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |