Published online Sep 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.101837

Revised: November 3, 2024

Accepted: November 19, 2024

Published online: September 20, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 7.6 Hours

Severe dengue children with critical complications have been attributed to high mortality rates, varying from approximately 1% to over 20%. To date, there is a lack of data on machine-learning-based algorithms for predicting the risk of in-hospital mortality in children with dengue shock syndrome (DSS).

To develop machine-learning models to estimate the risk of death in hospitalized children with DSS.

This single-center retrospective study was conducted at tertiary Children’s Hospital No. 2 in Viet Nam, between 2013 and 2022. The primary outcome was the in-hospital mortality rate in children with DSS admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Nine significant features were predetermined for further analysis using machine learning models. An oversampling method was used to enhance the model performance. Supervised models, including logistic regression, Naïve Bayes, Random Forest (RF), K-nearest neighbors, Decision Tree and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), were employed to develop predictive models. The Shapley Additive Explanation was used to determine the degree of contribution of the features.

In total, 1278 PICU-admitted children with complete data were included in the analysis. The median patient age was 8.1 years (interquartile range: 5.4-10.7). Thirty-nine patients (3%) died. The RF and XGboost models de

We developed robust machine learning-based models to estimate the risk of death in hospitalized children with DSS. The study findings are applicable to the design of management schemes to enhance survival outcomes of patients with DSS.

Core Tip: The in-hospital mortality rate of children with dengue shock syndrome (DSS) at a large tertiary pediatric hospital in Viet Nam was 3%. The supervised models showed good predictive value. In particular, the Random Forest and Extreme Gradient Boost models demonstrated the highest model performance. The supervised machine learning model showed that the nine most important predictive variables included younger age, presence of underlying diseases, severe transaminitis, critical bleeding, platelet transfusion requirement, elevated international normalized ratio and blood lactate levels, and high vasoactive inotropic score (> 30). Identification of mortality predictors in patients with DSS will help optimize management protocols to enhance survival outcomes.

- Citation: Vo LT, Vu T, Pham TN, Trinh TH, Nguyen TT. Machine learning-based models for prediction of in-hospital mortality in patients with dengue shock syndrome. World J Methodol 2025; 15(3): 101837

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i3/101837.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.101837

Dengue has posed a huge disease burden in tropical and subtropical countries, particularly Southeast Asia, South Asia, and South America, with its incidence increasing by 85.5% from 1990 to 2019 worldwide[1]. Dengue-associated severe complications have been attributed to increasing mortality rates, varying from 1% to > 20%[2,3]. Common severe dengue-related complications among hospitalized children include dengue shock syndrome (DSS), severe bleeding, acute liver failure, huge plasma leakage, and respiratory failure[4-7]. To date, many prognostic models for dengue-related death have been reported in adult cohorts; however, there are insufficient data on the pediatric population in this regard[8-12]. In addition, several published prognostic models to estimate the risk of death among hospitalized dengue children are restricted by the relatively limited sample size and the lack of robust statistical methods to determine the predictive model effect[3,4]. Notably, we recently reported a cohort of 492 hospitalized children with DSS to predict fatality; however, this study was restricted by the limited number of fatal outcomes (n = 26 deaths, 5.3%)[3]. Another prospective study cohort showed more important predictors of death in children with severe dengue; however, the study was limited by the small sample size of 78 pediatric patients included in the final analysis[4]. Recently, machine learning methods, with their high performance in prediction and classification, have achieved significant advances and applicability in a multitude of medical fields, particularly tropical diseases[13-15]. We aimed to use machine learning to identify the strong predictors of mortality among hospitalized children with DSS. Determining the predictors of death will aid in optimizing the prognosis and management protocols of hospitalized children with DSS to enhance survival outcomes.

This single-center retrospective cohort study, the Viet Nam Dengue-Infected Study, was conducted at Children’s Hospital No. 2 in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. This study included all pediatric patients admitted with DSS between 2013 and 2022. Data were collected from patient records to ensure the comprehensive coverage of clinical and laboratory variables relevant to patient outcomes. The inclusion criteria were age < 18 years, laboratory-confirmed dengue infection, and the presence of DSS[2]. The exclusion criteria were a lack of serological confirmation of dengue infection and missing data for covariables of interest (≥ 50%).

The main outcome was the in-hospital mortality rate in pediatric intensive care unit (PICU)-admitted children with DSS. Candidate predictors were predetermined based on clinical knowledge, disease pathogenesis, and medical literature, including patient age, underlying diseases on admission, systolic shock index, critical bleeding, severe transaminitis, international normalized ratio (INR), peak hematocrit (%), platelet cell count, platelet transfusion requirement, blood lactate, serum creatinine, cumulative fluid infused from referral hospitals and within 24 h PICU admission, colloid to crystalloid fluid infusion ratio, and vasoactive inotropic score (VIS).

The dataset was gathered from hospital medical records, originally comprising 1278 observations and 81 variables, and was classified into the following major categories:

Demographic data: Patient’s age, gender, and accompanied underlying diseases.

Clinical data: Day of onset of dengue shock, severity of dengue shock, severe bleeding, platelet transfusion, respiratory rate, systolic shock index, VIS, cumulative amount of fluid infused from the referral hospital and during 24 h of PICU admission, and colloid-to-crystalloid fluid infusion ratio.

Laboratory data: Hematological parameters, liver enzyme levels, and biomarkers indicating organ dysfunction.

Handling missing data: Missing data patterns were examined using the naniar, rms, VIM, and dlookr packages in R. Visualizations, such as missing data patterns, Pareto charts, and hierarchical clustering, were utilized to manipulate missing values. Variables with more than 50% missing data were excluded from the analysis. Missing data imputation was performed using Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) method. The MICE algorithm was performed with predictive mean matching, generating five imputed datasets with 50 iterations each.

Data cleaning and transformation: Categorical variables were converted into factors. Binary variables were converted into numeric (0/1) formats. Outliers and irrelevant categories were removed where applicable.

Feature selection: A predefined set of clinical and laboratory covariables was preselected using clinical knowledge, the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), and stepwise selection using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) method. To prevent overfitting by selecting a combination of predetermined features, we prudently manipulated the penalizing coefficient (lambda) from the LASSO regression in balance with the AIC method.

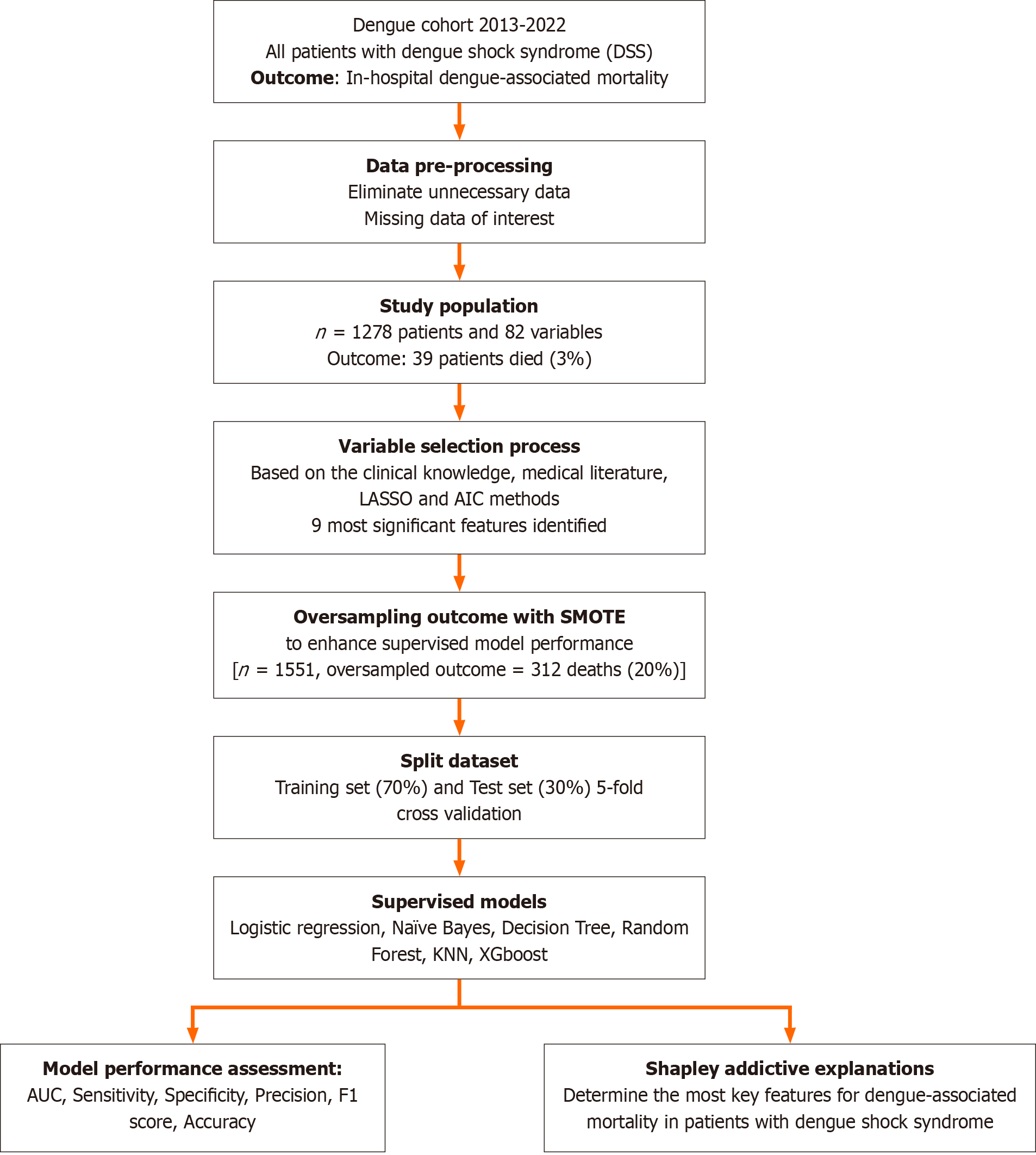

All steps in the predictive model development are described in Figure 1. The original dataset was first oversampled using the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) to address the mortality outcome imbalance[16]. After oversampling, the dataset was split into training (70%) and testing (30%) sets.

Supervised models were implemented, including logistic regression, Random Forest, Naive Bayes, Decision Tree, K-nearest neighbors (KNN) and Extreme Gradient Boost (XGBoost). The models were trained using 5-fold cross-validation to optimize the performance metrics. The hyperparameters were tuned using grid search to identify the optimal settings for each model. Performance metrics, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, area under the curve (AUC), and F1-score, were calculated with 95% confidence intervals for the test set using bootstrapping techniques.

Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) analysis was used to interpret the contribution of each feature to model predictions. The SHAP values provide insights into the contribution of each feature to the model's predictions. SHAP summary and dependence plots were generated to visualize the importance of individual features and their interactions with the outcome.

All study analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.2) with packages including tidyverse, compare Groups, rms, naniar, VIM, dlookr, missRanger, glmnet, caret, xgboost, SHAP forxgboost, ggplot2, and cutpointr. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Between 2013 and 2022, approximately 2000 children with DSS were admitted to the PICU, of whom 1278 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. Of these, 39 patients (3%) died in-hospital, whereas the remaining 1239 patients (97%) survived. Baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The non-survivors were generally younger and had a higher prevalence of underlying diseases. The occurrence of DSS was observed earlier in non-survivors, with a median duration of four days after the onset of fever. Patients who did not survive experienced greater disease severity, with a significantly higher proportion of patients developing decom

| Characteristics | Non-survivor (n = 39) | Survivors (n = 1239) | P value |

| Age (years) | 7 (5-10) | 8.1 (5.4-10.7) | 0.16 |

| Female sex | 18 (46) | 601 (49) | 0.77 |

| Underlying diseases | 7 (18) | 73 (6) | < 0.01 |

| Day of occurrence of dengue shock since onset of fever (days) | 4 (4-5) | 5 (4-5) | 0.09 |

| Grading of DSS | |||

| Compensated DSS | 11 (28) | 1143 (92) | < 0.001 |

| Decompensated DSS | 28 (72) | 96 (8) | |

| Severe bleeding | 29 (74) | 66 (5.3) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 30 (24-40) | 25 (22-30) | < 0.001 |

| Systolic shock index (bpm/mmHg) | 1.47 (1.33-1.88) | 1.3 (1.11-1.5) | < 0.01 |

| White blood cell count (× 109/L) | 7.15 (3.86-12.9) | 4.74 (3.36-6.7) | 0.93 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.8 (11.5-15.1) | 14.9 (13.5-16.1) | 0.01 |

| Peak hematocrit (%) | 46 (42-52) | 48 (45-51) | 0.07 |

| Nadir hematocrit (%) | 33 (29-34) | 38 (35-41) | 0.001 |

| Platelet cell count (× 109/L) | 25 (14-42.4) | 36 (23-55) | 0.21 |

| Platelet transfusion | 34 (87) | 129 (10.4) | < 0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 2219 (572-4458) | 148 (86-314) | < 0.001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 724 (324-1670) | 63 (34-149) | < 0.001 |

| Severe transaminitis | 25 (64) | 105 (9) | < 0.001 |

| International normalized ratio | 2.52 (1.83-3.57) | 1.21 (1.1-1.47) | < 0.001 |

| Blood lactate (mmol/L) | 7.2 (3.1-13) | 2.3 (1.6-3.1) | < 0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mmol/L) | 65 (56-111) | 51 (44-59) | 0.001 |

| Cumulative fluid infused from referral hospitals and 24 h of PICU admission (mL/kg) | 301 (220-393) | 133 (104-176) | < 0.001 |

| Ratio of colloid-to-crystalloid infusion | 6.0 (1.7-9.1) | 0.7 (0-2.0) | < 0.001 |

| Vasoactive inotropic score during first 24 h | 60 (40-165) | 0 (0-15) | < 0.001 |

| Vasoactive inotropic score > 30 | 30 (79) | 17 (13) | < 0.001 |

As presented in Table 2, in the multivariable logistic regression, the full predefined model showed significant clinical predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with DSS, including accompanying underlying diseases, severe bleeding, high INR, platelet transfusion requirement, elevated blood lactate and serum creatinine levels, larger volume of fluid infusion from referral hospitals and 24 h of PICU admission, and a high VIS (> 30). No significant interactions were found between the covariates. Multivariable analyses from the LASSO and AIC methods generated results similar to those from the full predefined model. However, the LASSO penalized underlying diseases as insignificant variables in the final model, whereas the AIC preserved this covariate in the final model. Although both LASSO and AIC models disregarded age variables, we retained this covariate in the final prognostic models based on its clinical importance in disease pathogenesis and the medical literature.

| Candidate predictors | Full model1 | Reduced model 12 | Reduced model 23 | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.85 (0.71-1.02) | 0.09 | 0.93 (0.8-1.08) | 0.32 | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) | 0.39 |

| Underlying diseases | 5.14 (1.22-21.7) | 0.03 | 4.1 (1.02-16.3) | 0.04 | ||

| Systolic shock index (mmHg/bpm) | 0.46 (0.08-2.48) | 0.36 | ||||

| Severe bleeding | 4.28 (1.37-13.4) | 0.01 | 3.38 (1.19-9.57) | 0.02 | 3.38 (1.2-9.58) | 0.02 |

| Severe transaminitis | 1.16 (0.4-3.38) | 0.78 | ||||

| International normalized ratio | 1.56 (1.12-2.17) | < 0.01 | 1.45 (1.05-1.99) | 0.02 | 1.47 (1.07-2.01) | 0.01 |

| Peak hematocrit (%) | 1.08 (1.0-1.16) | 0.05 | ||||

| Platelet counts (< 20 × 10 9/L) | 0.95 (0.32-2.85) | 0.92 | ||||

| Platelet transfusion | 4.48 (1.11-18.1) | 0.03 | 4.1 (1.07-15.7) | 0.03 | 4.89 (1.27-18.9) | 0.02 |

| Blood lactate (mmol/L) | 1.2 (1.02-1.41) | 0.03 | 1.2 (1.04-1.39) | 0.01 | 1.19 (1.03-1.37) | 0.02 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 1.02 (1.0-1.03) | 0.01 | 1.01 (1-1.03) | 0.09 | 1.01 (1.0-1.03) | 0.06 |

| Log-2 Cumulative fluid infused from referral hospitals and within 24 h-PICU admission (mL/kg)4 | 2.76 (1.25-6.1) | 0.01 | 3.69 (1.95-7.0) | < 0.001 | 3.61 (1.88-6.91) | < 0.001 |

| Colloid to crystalloid fluid infusion ratio | 1.07 (0.98-1.17) | 0.15 | ||||

| Vasoactive inotropic score (> 30) | 9.58 (2.36-39) | < 0.01 | 4.78 (1.49-15.4) | < 0.01 | 4.59 (1.42-14.8) | 0.01 |

Table 3 summarizes the performance parameters of various supervised machine learning models employed to estimate the risk of in-hospital mortality in patients with DSS. The logistic regression model achieved an AUC of 0.92 (95%CI: 0.90-0.94), with a sensitivity of 0.99, low specificity of 0.50, precision of 0.98, F1 score of 0.61, and an accuracy of 0.97. The Naïve Bayes model further revealed an AUC of 0.86 (95%CI: 0.70-1), sensitivity 0.91, specificity 0.82, precision 0.83, F1 score 0.87, and an accuracy of 0.86. The Random Forest model demonstrated high performance with an AUC of 0.86 (95%CI: 0.69-1), sensitivity 0.82, specificity 0.91, precision 0.90, F1 score and accuracy of 0.86. In addition, the KNN model yielded almost similar results to the Random Forest model. The Decision Tree model exhibited an AUC of 0.77 (95%CI: 0.59-0.94), sensitivity 0.82, specificity 0.73, precision 0.75, F1 score 0.78, and an accuracy of 0.77. Finally, the XGBoost model also performed well, with an AUC of 0.86 (95%CI: 0.71-1), sensitivity 0.82, specificity 0.91, precision 0.90, F1 score and an accuracy of 0.86. Considering the performance of all these models, the Random Forest, KNN, and XGBoost models demonstrated the highest performance across multiple metrics, indicating their strong predictive capabilities.

| Models | AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision | F1 score | Accuracy |

| Logistic regression | 0.92 (0.90-0.94) | 0.99 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 0.61 | 0.97 |

| Naïve Bayes | 0.86 (0.70-1) | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| Random forest | 0.86 (0.69-1) | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| KNN | 0.86 (0.71-1) | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Decision tree | 0.77 (0.59-0.94) | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| XGBoost | 0.86 (0.71-1) | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

Table 4 summarizes the performance of the supervised machine learning models in predicting the in-hospital mortality in DSS patients when oversampling with SMOTE was employed. Overall, all supervised models using the SMOTE method showed superior performance compared to the models without SMOTE applicability. The XGBoost model demonstrated excellent performance compared with the other models.

| Models | AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision | F1 score | Accuracy |

| Logistic regression | 0.93 (0.89-0.97) | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.93 |

| Naïve Bayes | 0.94 (0.91-0.97) | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.94 |

| Random forest | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.97 |

| KNN | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.90 |

| Decision tree | 0.95 (0.92-0.98) | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.96 |

| XGBoost | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.96 |

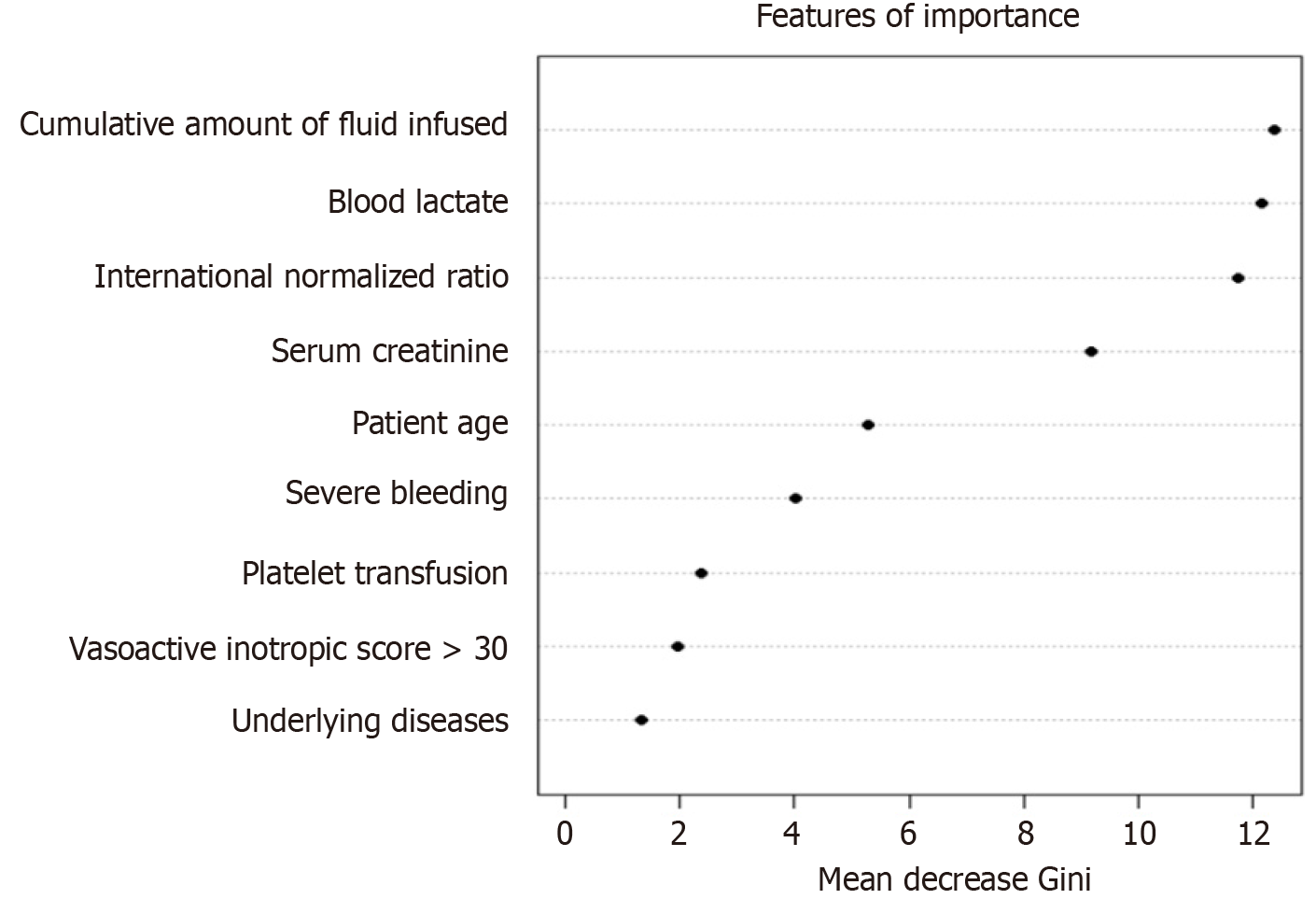

As presented in Figure 2, the oversampled random-forest model showed the most significant features (ranked by the Gini score), including the cumulative amount of fluid infused from the referral hospital and during the 24 h of admission, blood lactate, INR, and serum creatinine. Other important features included younger age, female patients, severe bleeding, low platelet count requiring platelet transfusion, a high VIS score, and underlying diseases.

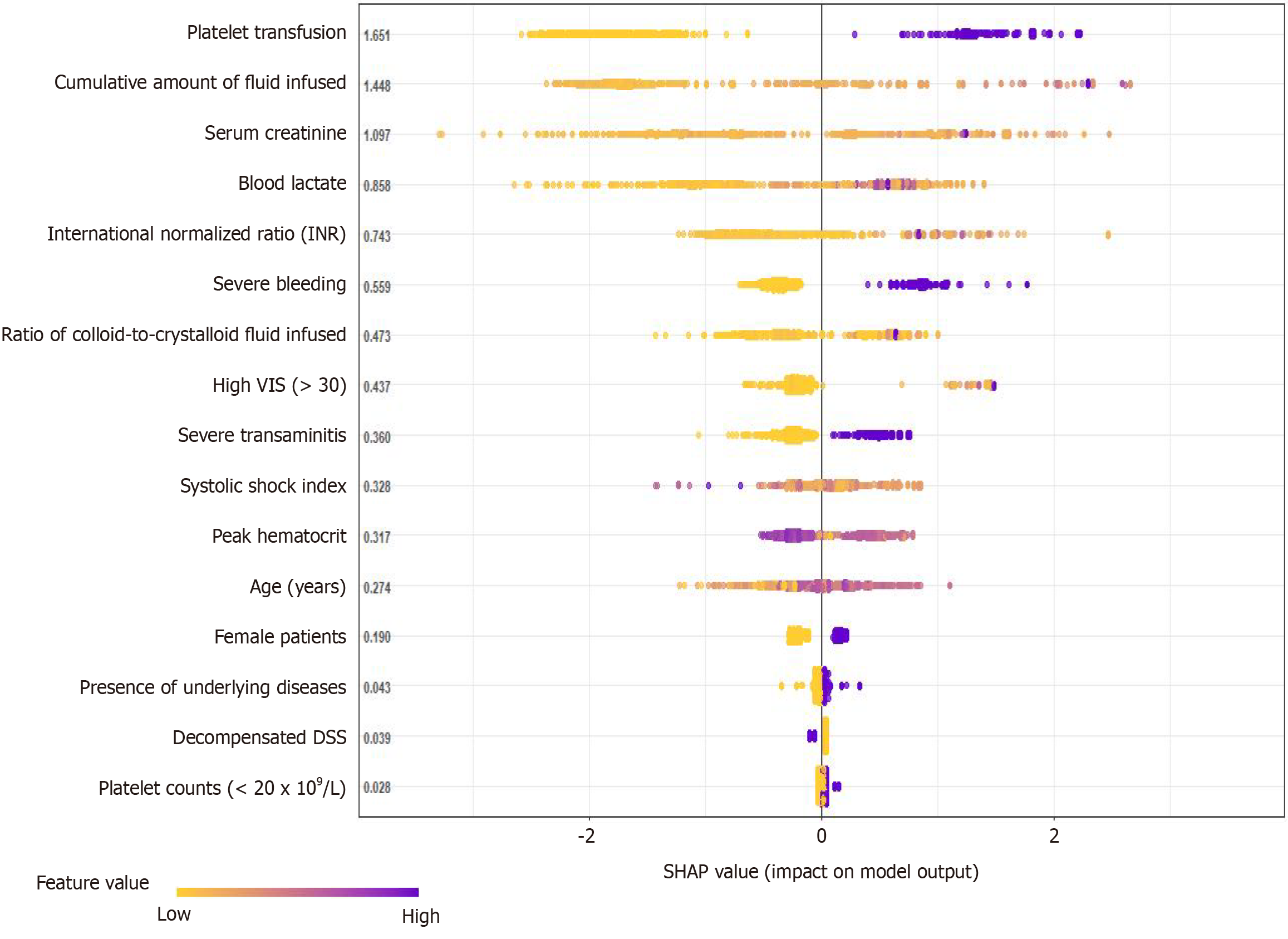

The SHAP model identified key variables contributing to the risk of fatality in children with severe dengue who were admitted to the PICU. The SHAP plot highlights the most important predictors contributing to the risk of death in hospitalized children with DSS, as presented in Figure 3. Among predetermined covariates, platelet transfusion had the highest SHAP value, making it the most important predictor of mortality. The cumulative amount of fluid infusion was also a major contributing factor. A larger volume of intravenous infusion and more colloids than crystalloid fluid administration were highly associated with an increased risk of mortality. Elevated serum creatinine and lactate levels were significant predictors of mortality. Critical hepatic injury, high INR, and severe bleeding highly predicted mortality in patients with DSS. A high systolic shock index and VIS (> 30) were substantial contributors to the mortality risk, reflecting the hemodynamic instability of patients. Peak hematocrit levels were highlighted as a relevant factor, while demographic variables, such as age and sex also played a role in predicting mortality, with older age surprisingly showing a protective effect in contrast to the younger population. The presence of underlying diseases, decompensated DSS, and platelet counts (< 20 × 109/L) had lower SHAP values, indicating that they were less influential than other variables.

Severe DSS significantly increases the risk of mortality among hospitalized children by up to 20%. Therefore, identifying prognostic factors associated with mortality in patients with DSS is imperative to optimize the allocation of medical resources, enhance monitoring capabilities, and prioritize treatment strategies to improve patient survival rates.

This study aimed to construct and validate predictive models for assessing the mortality risk in pediatric patients diagnosed with DSS. By analyzing data from 1278 patients, we identified 39 fatalities, corresponding to a mortality rate of 3%. Key variables incorporated into the final predictive model included severe bleeding, INR, platelet transfusion requirement, blood lactate levels, serum creatinine, cumulative intravenous fluid infusion from referral hospitals and within the first 24 h of PICU admission, and a VIS exceeding 30. These predictors exhibited robust predictive power for mortality risk, thereby offering valuable insights into the clinical management and prognosis improvement in patients with DSS. Our findings are consistent with the existing literature on the mortality risk factors for severe DSS. Each variable was carefully predetermined based on the pathophysiological relevance of the disease and corroborated with previous studies. Notably, our study distinguished itself by employing advanced machine learning techniques, such as Random Forest and XGBoost, to validate the reliability of the model. In this study, severe bleeding was demonstrated to be a critical prognostic factor, which is consistent with previous studies[17,18]. The INR, reflecting coagulation dys

To date, there are scant data on the prognostic value of estimating the risk of in-hospital death among pediatric patients. A small prospective cohort (n = 78 children with severe dengue) revealed significant clinical predictors of mortality among hospitalized children, including increased blood lactate levels, VIS, and positive fluid balance[4]. In addition, we recently developed a conventional statistical model to predict the in-hospital mortality in 492 PICU-admitted children with DSS. We also showed prognosticators for mortality in DSS children, including critical bleeding, high volume of fluid infusion, elevated blood lactate and increased VIS (> 30) during the first 24 h of PICU admission[3]. However, the study was restricted by its retrospective design, high rate of missing data for biochemistry tests, and small number of fatal outcomes (n = 26 deaths, 5.3%). The limitations of the inadequate sample size in the aforementioned studies cannot be manipulated by the conventional statistical analysis. A similar issue was observed in the current study, as there were 39 deaths (3%) among the sample size of 1278 children with DSS. To address this issue, we implemented the SMOTE. This approach effectively mitigated data imbalance and enhanced the model performance beyond that achieved by conventional statistical methods. After adjustment with the SMOTE, all supervised machine learning models showed a dramatic improvement in the performance metrics, and the XGBoost model demonstrated the best performance in predicting the risk of mortality.

Considering its simplicity, conventional statistical modelling has gained wide popularity among researchers. However, it requires a priori assumptions, a refined set of clinically important variables consistent with the underlying biological mechanisms, an adequate sample size to ensure study power, and an appropriate number of outcomes compared to the total predictors in the predictive models[20]. However, machine learning models are abstract to interpret, with or without a priori assumptions and oversampling techniques for limited outcome events. Notably, machine learning modelling has a weakness in that it is prone to overfitting. Hence, we integrated the two methods of conventional and machine learning analyses to maximize the strength of both techniques in our study. We based the AIC and LASSO methods on a predetermined set of features, and these conventional methods helped minimize overfitting, which is commonly associated with machine learning. Oversampling with the SMOTE significantly enhanced the study power and model performance metrics.

The XGBoost-based SHAP model was developed to evaluate the importance of SHAP values and the magnitude of the impact of each clinical predictor. Notably, the most significant predictors of in-hospital mortality among DSS patients were platelet transfusion requirement, critical bleeding, severe coagulation disorder and transaminitis, high VIS (> 30), large volume of fluid infused with more colloids than crystalloids, kidney failure, and high serum lactate levels. These prognostic factors had high-ranking SHAP values, reflecting their greater significance in the mortality prediction model for DSS. Furthermore, the SHAP model also revealed that other covariables, including demographic factors (age and sex), underlying diseases, and severity of dengue shock, were less important in the final prognostic model, as indicated by the small and narrow magnitudes of the SHAP values. Therefore, the SHAP model provides a transparent interpretation of how each variable affects the overall model's decisions, offering a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between the predictors and mortality risk. Interventions targeting the clinical predictors of high weight, as mentioned above, can significantly improve the survival outcomes of children with DSS.

This study has several significant implications for clinical practice. First, these machine learning-based predictive models can potentially transform the prognosis and management of hospitalized children with DSS. In particular, the XGBoost model had the highest predictive accuracy, identifying critical factors including younger age, female sex, underlying diseases, severe transaminitis, critical bleeding, low platelet counts necessitating transfusion, high INR, elevated blood lactate and serum creatinine levels, a large volume of resuscitation fluid, and a VIS > 30. Second, this result can be manipulated to design therapeutic schemes based on modifiable factors such as platelet transfusion, judicious administration of infused fluid and vasopressors, and management of critical transaminases. Third, a risk-scoring system can be developed based on the identified predictors from supervised and SHAP models to classify high- and low-risk mortality groups. This will aid clinicians in early recognition and assessment of the disease severity among hospitalized children with DSS. Therefore, interventions targeting these predictors can significantly improve the survival outcomes of children with DSS.

However, this study had certain limitations. First, as this was a single-center retrospective study, the generalizability of the findings to other treatment centers or diverse patient populations may be limited. Second, despite employing sophisticated techniques to process data and mitigate imbalances, missing or incomplete data might have had an impact on the analysis. Finally, there was variability in treatment standards during the study period from 2013 to 2022. In our study, the study population included children presenting with DSS, which has been well reported as the most common complication of severe dengue and is attributed to a high mortality rate (up to 20%)[2]. Thus, the study findings can be externally validated in WHO-reported regions with the highest dengue-related burdens, particularly South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia[1,2]. External validation across different dengue-endemic regions will increase the validity and generalizability of the model developed in this study.

We developed robust machine-learning-based models to estimate the risk of mortality in hospitalized children with DSS. The study findings can be manipulated to optimize the prognosis and management of children with severe dengue and enhance patient survival outcomes.

We are grateful to the patients and administrative staff, for their support with this study.

| 1. | Yang X, Quam MBM, Zhang T, Sang S. Global burden for dengue and the evolving pattern in the past 30 years. J Travel Med. 2021;28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control: New Edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009– . [PubMed] |

| 3. | Nguyen Tat T, Vo Hoang-Thien N, Nguyen Tat D, Nguyen PH, Ho LT, Doan DH, Phan DT, Duong YN, Nguyen TH, Nguyen TK, Dinh HT, Dinh TT, Pham AT, Do Chau V, Trinh TH, Vo Thanh L. Prognostic values of serum lactate-to-bicarbonate ratio and lactate for predicting 28-day in-hospital mortality in children with dengue shock syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e38000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Sachdev A, Pathak D, Gupta N, Simalti A, Gupta D, Gupta S, Chugh P. Early Predictors of Mortality in Children with Severe Dengue Fever: A Prospective Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40:797-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Laoprasopwattana K, Khantee P, Saelim K, Geater A. Mortality Rates of Severe Dengue Viral Infection Before and After Implementation of a Revised Guideline for Severe Dengue. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vo LT, Do VC, Trinh TH, Vu T, Nguyen TT. Combined Therapeutic Plasma Exchange and Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy in Children With Dengue-Associated Acute Liver Failure and Shock Syndrome: Single-Center Cohort From Vietnam. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2023;24:818-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Preeprem N, Phumeetham S. Paediatric dengue shock syndrome and acute respiratory failure: a single-centre retrospective study. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2022;6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Amâncio FF, Heringer TP, de Oliveira Cda C, Fassy LB, de Carvalho FB, Oliveira DP, de Oliveira CD, Botoni FO, Magalhães Fdo C, Lambertucci JR, Carneiro M. Clinical Profiles and Factors Associated with Death in Adults with Dengue Admitted to Intensive Care Units, Minas Gerais, Brazil. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pinto RC, Castro DB, Albuquerque BC, Sampaio Vde S, Passos RA, Costa CF, Sadahiro M, Braga JU. Mortality Predictors in Patients with Severe Dengue in the State of Amazonas, Brazil. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mallhi TH, Khan AH, Sarriff A, Adnan AS, Khan YH. Determinants of mortality and prolonged hospital stay among dengue patients attending tertiary care hospital: a cross-sectional retrospective analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Huy BV, Hoa LNM, Thuy DT, Van Kinh N, Ngan TTD, Duyet LV, Hung NT, Minh NNQ, Truong NT, Chau NVV. Epidemiological and Clinical Features of Dengue Infection in Adults in the 2017 Outbreak in Vietnam. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:3085827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kaur G, Kumar V, Puri S, Tyagi R, Singh A, Kaur H. Predictors of dengue-related mortality in young adults in a tertiary care centre in North India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:694-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sarker IH. Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions. SN Comput Sci. 2021;2:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 751] [Article Influence: 187.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sippy R, Farrell DF, Lichtenstein DA, Nightingale R, Harris MA, Toth J, Hantztidiamantis P, Usher N, Cueva Aponte C, Barzallo Aguilar J, Puthumana A, Lupone CD, Endy T, Ryan SJ, Stewart Ibarra AM. Severity Index for Suspected Arbovirus (SISA): Machine learning for accurate prediction of hospitalization in subjects suspected of arboviral infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0007969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Huang SW, Tsai HP, Hung SJ, Ko WC, Wang JR. Assessing the risk of dengue severity using demographic information and laboratory test results with machine learning. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dablain D, Krawczyk B, Chawla NV. DeepSMOTE: Fusing Deep Learning and SMOTE for Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34:6390-6404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yuan K, Chen Y, Zhong M, Lin Y, Liu L. Risk and predictive factors for severe dengue infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0267186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sangkaew S, Ming D, Boonyasiri A, Honeyford K, Kalayanarooj S, Yacoub S, Dorigatti I, Holmes A. Risk predictors of progression to severe disease during the febrile phase of dengue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:1014-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Md-Sani SS, Md-Noor J, Han WH, Gan SP, Rani NS, Tan HL, Rathakrishnan K, A-Shariffuddin MA, Abd-Rahman M. Prediction of mortality in severe dengue cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rajula HSR, Verlato G, Manchia M, Antonucci N, Fanos V. Comparison of Conventional Statistical Methods with Machine Learning in Medicine: Diagnosis, Drug Development, and Treatment. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |