Published online Sep 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.100903

Revised: October 24, 2024

Accepted: November 25, 2024

Published online: September 20, 2025

Processing time: 181 Days and 14.4 Hours

Knowledge-based systems (KBS) are software applications based on a knowledge database and an inference engine. Various experimental KBS for computer-assisted medical diagnosis and treatment were started to be used since 70s (VisualDx, GIDEON, DXPlain, CADUCEUS, Internist-I, Mycin etc.).

To present in detail the “Electronic Pediatrician (EPed)”, a medical non-machine learning artificial intelligence (nml-AI) KBS in its prototype version created by the corresponding author (with database written in Romanian) that offers a physio

EPed specifically focuses on the physiopathological reasoning of pediatric clinical cases. EPed has currently reached its prototype version 2.0, being able to diagnose 302 physiopathological macro-links (briefly named “clusters”) and 269 pediatric diseases: Some examples of diagnosis and a previous testing of EPed on a group of 34 patients are also presented in this paper.

The prototype EPed can currently diagnose 269 pediatric infectious and non-infectious diseases (based on 302 clusters), including the most frequent respira

EPed is the first and only physiopathology-based nml-AI KBS focused on general pediatrics and is the first and only pediatric Romanian KBS addressed to medical professionals. Furthermore, EPed is the first and only nml-AI KBS that offers not only both a physiopathology-based differential and positive disease diagnosis, but also identifies possible physiopathological “clusters” that may explain the signs and symptoms of any child-patient and may help treating that patient physiopathologically (until a final diagnosis is found), thus encouraging and developing the physiopathological reasoning of any clinician.

Core Tip: Electronic Pediatrician (EPed) is the first and only physiopathology-based non-machine learning artificial intelligence (nml-AI) knowledge-based system (KBS) focused on general pediatrics and is the first and only Romanian pediatric KBS addressed to medical professionals. Furthermore, EPed is the first and only nml-AI KBS that offers not only both a physiopathology-based differential and positive disease diagnosis, but also identifies possible physiopathological “clusters” that may explain the signs and symptoms of any child-patient and may help treating that patient physiopathologically (until a final diagnosis is found), thus encouraging and developing the physiopathological reasoning of any clinician.

- Citation: Drăgoi AL, Nemeș RM. “Electronic Pediatrician”, a non-machine learning prototype artificial intelligence software for pediatric computer-assisted pathophysiologic diagnosis ― general presentation. World J Methodol 2025; 15(3): 100903

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i3/100903.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.100903

Knowledge-based systems (KBS) are software with 2 pivotal components: (1) A knowledge (data-)base (KB); and (2) An inference engine (which deduces new information based on that KB)[1-3].

Medical expert systems (MES)[4] are artificial intelligence (AI)-based KBS[5-7] which emulate human experts and can be used as important adjuvants in clinical decision making[8].

However, because MES are mainly based on if–then rules, they are hard to build and maintain, thus quite expensive. Some examples of MES are: VisualDx (focused on dermatology), GIDEON & Mycin (both focused on infectious diseases), DXplain[9-12], CADUCEUS, Internist-I (all focused on internal medicine) etc[13,14].

The here-proposed software application “Electronic Pediatrician (EPed)” (built as a prototype by the corresponding author of this article) is a non-machine learning AI (nml-AI) KBS, a much cheaper alternative for MES, with other two main advantages: (1) EPed is the first nml-AI KBS written in Romanian and focused on general pediatrics; and (2) EPed is the first and only physiopathology-based nml-AI KBS that offers both a list of possible diseases for any proposed child-patient and a list of possible pathophysiological “clusters” that may explain the set of clinical and paraclinical signs of that child-patient (and thus help treating the patients physiopathologically until a specific disease diagnosis is obtained) encouraging and developing the physiopathological reasoning of any clinician (thus having potential pedagogical importance in the future, including a helpful resource in orientating the anamnesis and the clinical exam). This EPed prototype was also tested on a group of selected patients treated in the Children’s Infectious Diseases Ward of The Emergency County Hospital Târgoviște (Romania).

The “cluster” concept (used by EPed) is defined as any morphological and/or functional anomaly (macroscopic or microscopic) that produces at least one non-trivial clinical or paraclinical sign (or symptom) and can be a physiopathological macro-link in the physiopathogenic chain of one or more diseases or syndromes. This “cluster” concept is much wider and flexible than a “syndrome” because it contains all the clinical and paraclinical signs of a specific physiopathological process: For example, the “pharyngitis” cluster is defined as “an acute or chronic infectious/non-infectious inflammation of the pharynx” plus all the non-trivial clinical and paraclinical signs generated by this inflammation; the same for laryngitis, epiglottitis, sinusitis etc.

EPed uses 7 major types of clusters [each having a relatively specific clinico-paraclinical picture (CPP)], which can be regarded as modules of "healthy" physiopathological clinical reasoning of any medical professional: (1) Syndromes that can also have the role of physiopathological macro-links in various diseases, for example: Respiratory functional syndrome, central neuron syndrome, peripheral neuron syndrome, etc.; (2) Inflammation of various tissues, anatomical structures, organs, etc., for example: "pharyngitis" (defined as acute/chronic infectious/non-infectious inflammation of the pharynx), "laryngitis" (defined as acute/chronic infectious/non-infectious inflammation of the larynx), etc.; (3) Deformities (including cracks/ruptures) of tissues, anatomical structures and organs, etc., for example: Left ventricular hypertrophy, right ventricular hypertrophy, etc.; (4) Various functional imbalances, for example: Left systolic ventricular failure, left diastolic ventricular failure, etc.; (5) Various metabolic/homeostatic imbalances, for example: Metabolic acidosis, respiratory acidosis, hypoxia, hypoxemia, etc.; (6) Changes in lab parameters (e.g. hypernatremia, hyperkalemia, direct/total hyperbilirubinemia) that also produce at least one non-trivial sign/symptom (different from the name of the cluster): For example, hypernatremia also produces non-trivial clinical signs (e.g. convulsions), etc.; and (7) Various genetic abnormalities (each with a certain CPP), for example: Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome), mutations of the dystrophin gene (muscular dystrophies Duchenne, Becker) etc.

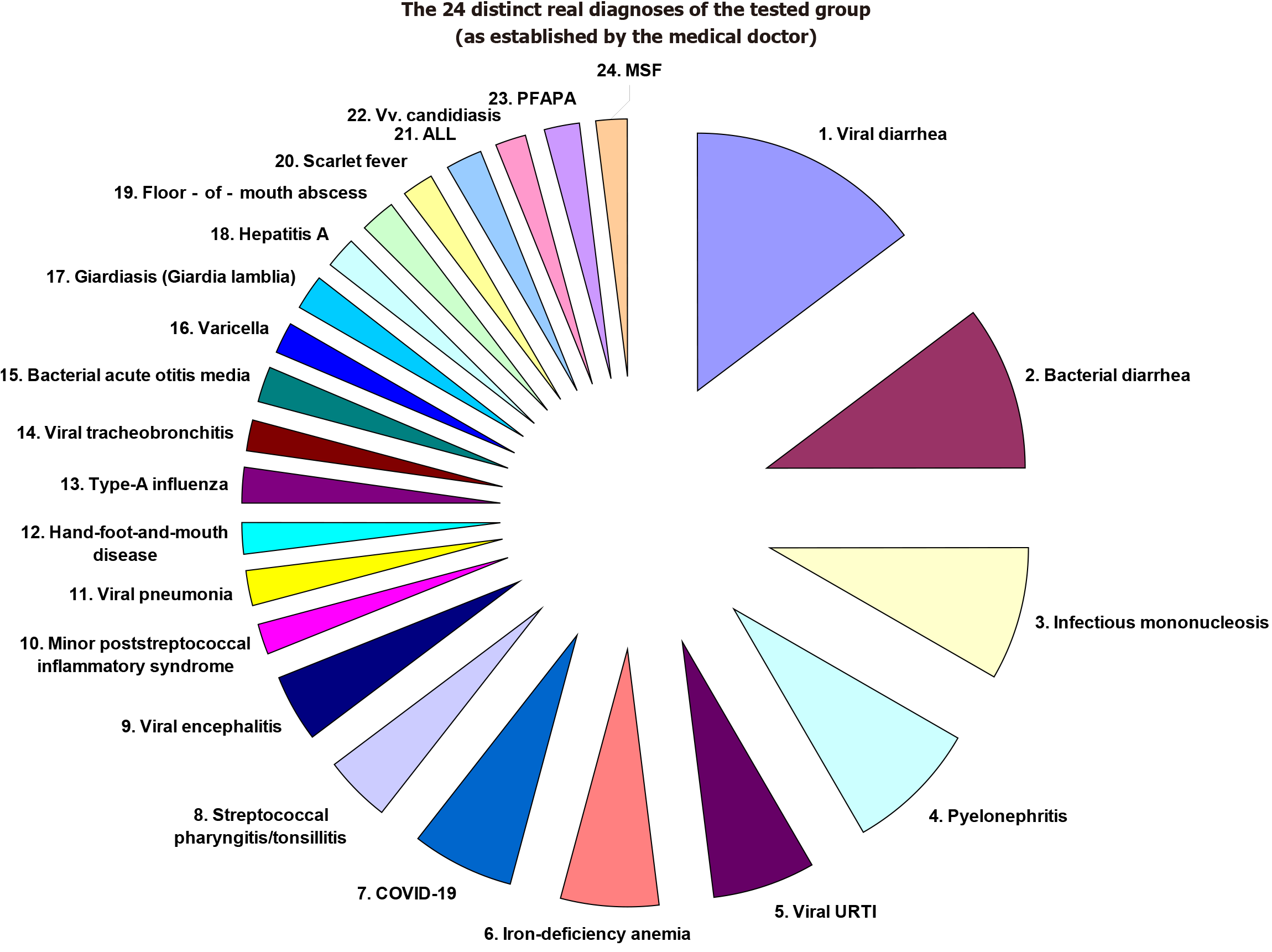

For example, acute viral hepatitis A (VHA) is described in EPed by a specific set of clusters: (1) Viremia (predefined by EPed as the presence of the Hepatovirus A in the bloodstream); (2) Hepatitis (predefined by EPed as the non-specific global inflammation of the liver); (3) Hepatocytolysis (predefined by EPed as the necrosis of hepatocytes); (4) Intrahepatic cholestasis; (5) Extrahepatic cholestasis (that may sometimes complicate VHA); (6) Biological/systemic inflammatory syndrome (predefined by EPed as the increase in serum levels of the main inflammatory markers); (7) Cholecystitis (predefined by EPed as the nespecific inflammation of the biliary vesicle that may sometimes appear in VHA); (8) Cholangitis (that may sometimes complicate VHA); and (9) Gastritis (predefined by EPed as the inflammation of the gastric mucosa that may sometimes appear in VHA). Note: (1) The “cluster” concept can be regarded as a “vertical synapse” between various biochemical (microscopic) sub-processes of any disease (the pathophysiological micro-links of that disease) and the (macroscopic) clinical signs and symptoms of a patient. EPed essentially tries to create a common and unifying physiopathological language between several pediatric subspecialties (and not only!) by using this “cluster” concept as a unifying binder with a central role in the general algorithm of diagnosis and treatment proposed by EPed; (2) EPed primarily uses clusters to ultra-concisely describe diseases and to generate a physiopathology-based complex/combined differential diagnosis on N clinical/paraclinical signs (CPS)/symptoms simultaneously, an advantage impossible to be accomplished by any medical/pediatric manual: Furthermore, the physiopathological foundation of this complex differential diagnosis is not found in any other software of computer-assisted medical diagnosis; and (3) Moreover, EPed also has a promising performance in establishing a pediatric positive diagnosis, as we have already shown in a recent article in which we’ve tested EPed on 34 child-patients with 24 distinct real diagnoses established by the medical doctor[15] (Table 1; Figure 1).

| The real diagnoses of the tested group (as established by the medical doctor) | The number of tested cases per each real diagnosis (also in percents from the n = 34 patients in total) (%) | The indexed cases tested for each diagnosis in part |

| Viral diarrhea (rotavirus, norovirus, SARS-CoV2, adenovirus) | 7 (21) | Cases No. 4, 5, 6, 14, 17, 19, 25 |

| Bacterial diarrhea (Clostridium, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shigella) | 5 (15) | Cases No. 1, 5, 7, 14, 15, 18 |

| Infectious mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus and/or citomegalovirus) | 4 (12) | Cases No. 2, 23, 27, 34 |

| Pyelonephritis (ESBL-neg./pos. E. coli) | 4 (12) | Cases No. 4, 24, 29, 30 |

| Viral URTI (adenovirus) | 3 (9) | Cases No. 8, 25, 30 |

| Iron-deficiency anemia | 3 (9) | Cases No. 8, 15, 29 |

| COVID-19 (both respiratory and digestive forms of COVID-19) | 3 (9%) | Cases No. 10, 16, 19 |

| Streptococcal pharyngitis/tonsillitis | 2 (6) | Cases No. 3, 33 |

| Viral encephalitis (varicella-zoster virus) | 2 (6) | Cases No. 12, 22 |

| Minor poststreptococcal inflammatory syndrome | 1 (3) | Case No. 4 |

| Viral pneumonia | 1 (3) | Case No. 6 |

| Hand-foot-and-mouth disease | 1 (3) | Case No. 8 |

| Type-A influenza | 1 (3) | Case No. 9 |

| Viral tracheobronchitis | 1 (3) | Case No. 11 |

| Bacterial acute otitis media | 1 (3) | Case No. 11 |

| Varicella | 1 (3) | Case No. 12 |

| Giardiasis (Giardia lamblia) | 1 (3) | Case No. 13 |

| Hepatitis A | 1 (3) | Case No. 20 |

| Floor-of-mouth abscess (sublingual gland abscess) | 1 (3) | Case No. 21 |

| Scarlet fever | 1 (3) | Case No. 26 |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | 1 (3) | Case No. 28 |

| Vulvovaginal (Vv.) candidiasis | 1 (3) | Case No. 30 |

| Marshall syndrome (PFAPA) | 1 (3) | Case No. 31 |

| Mediterranean spotted fever (Rickettsia conorii) (confirmed by pos. IgM anti-Rickettsia conorri) | 1 (3) | Case No. 32 |

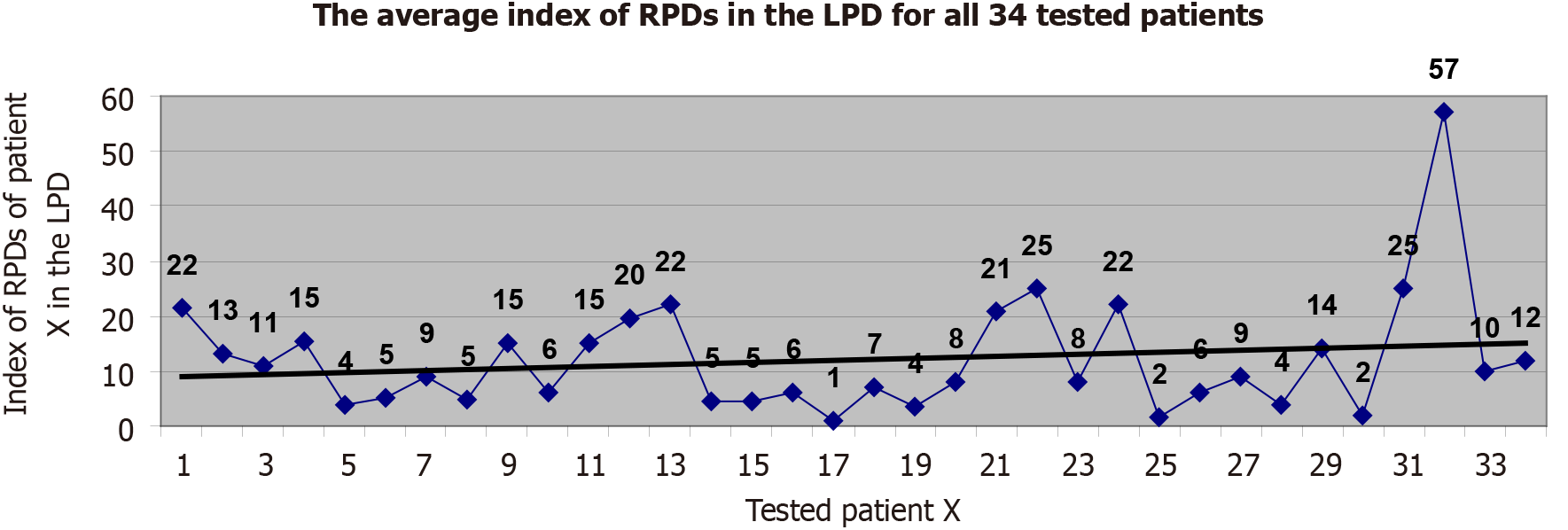

The real positive-diagnoses (established by the medical doctor for each tested child-patient in part) were found to occupy an average list-index of 12 (varying from 1 to 57) in the list of possible disease-diagnoses proposed by EPed for each input case in part, which is an acceptable performance of medical positive diagnostic performance for a prototype version (Figure 2).

Furthermore, in 2025, we plan to retrospectively test the positive-diagnosis performance of EPed on at least 1000 Romanian child-patients from at least one major Romanian hospital, with a total of at least 200-250 distinct diagnoses.

The 2-steps diagnosis accomplished by EPed: EPed uses an original 2-steps physiopathology-based differential diagnostic algorithm: (1) Finding all possible clusters that may explain the set of clinical and paraclinical signs of a child-patient; and (2) Finding all possible diseases containing those previously found possible clusters. Important note. EPed uses a newly-proposed universal diagnostic algorithm based on Occam's razor (the parsimony principle) also combined with the relative incidence (RI) of diseases.

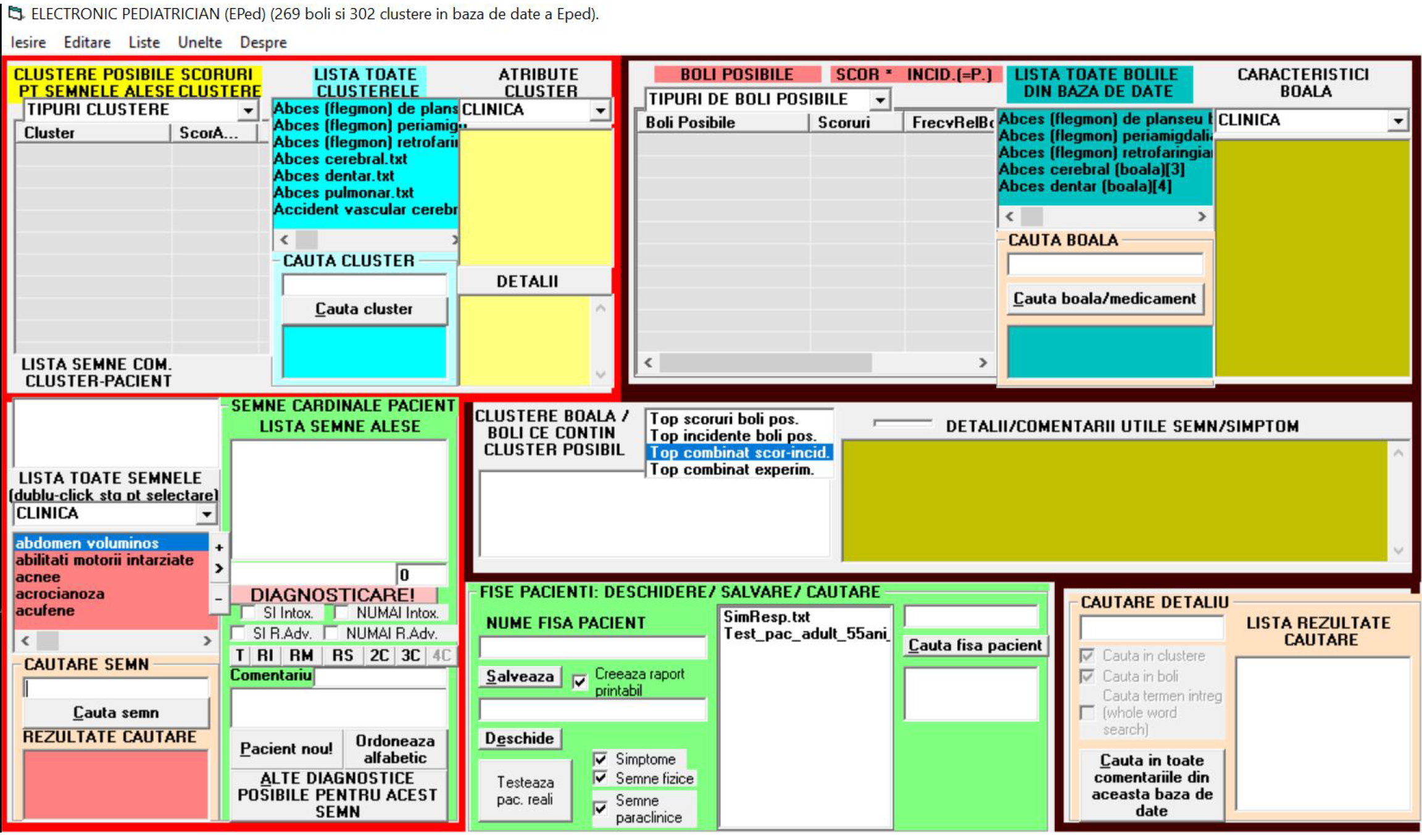

The structure of EPed: As a nml-AI KBS, EPed has 2 major components: (1) A medical knowledge database (composed of text files describing clusters and diseases respectively) and (2) A processing engine (which analyzes any child-patient and offers lists of possible clusters and diseases for that child-patient).

The interface of EPed: EPed has an interface window (IW) with 2 main sections: (1) (The lower-half of IW) by which the user can rapidly gather (by using predefined lists of terms) all the clinical and paraclinical signs of a child-patient; and (2) (The upper-half of IW) containing the lists of possible clusters and diseases proposed by EPed for that child-patient (Figure 3).

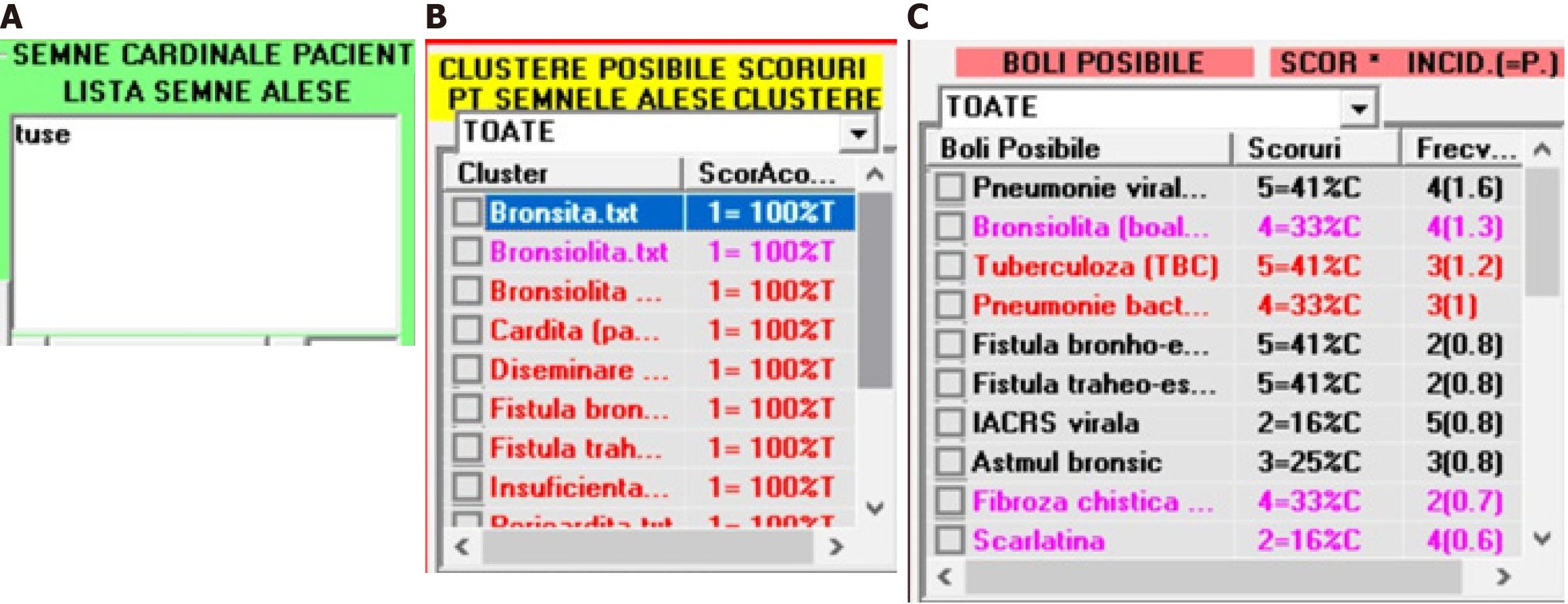

The steps of using EPed are listed next: (1) The user adds any CPS to a distinct list dedicated to the CPP of a child-patient. See the next figure in which the user has added the “cough” symptom (“tuse” in Romanian) to the list dedicated to CPP (Figure 4A); and (2) After all CPS (gathered from a patient) are added in the CPP-list, EPed automatically analyzes that CPP-list and finds all possible clusters (Figure 4B) and diseases (diseases that contain at least one of the possible clusters). This 2nd step has two sub-steps: (1) For each possible cluster, EPed calculates a coverage score (CS) which measures the percent in which that CPP-list is explainable by that possible cluster found; and (2) EPed then generates a list of possible diseases (LPD) that may explain at least one cluster from the list of possible clusters (LPC). For each disease (from LPD), 3 types of scores are calculated and assigned to that disease: (1) The RI of that specific disease (1 = very rare; 2 = rare; 3 = medium incidence; 4 = frequent; 5 = very frequent); (2) A cluster CS (CCS) measuring the percent of LPC that can be explained by each possible disease in part; and (3) A combined score of any (possible) disease CSD = RI*CCS (Figure 4C).

This section of the paper offers an example of a simulation based on a processed respiratory CPP: EPed generates both an LPC and LPD for this given respiratory CPP (Table 2).

| A respiratory CPP example | The possible clusters that may partially or integrally explain the given respiratory CPP (%) | The possible diseases that may explain the possible clusters found by EPed |

| This CPP example contains these 7 listed signs (which are simultaneously processed as a single CPP | EPed has found many possible clusters that may partially explain the given respiratory CPP (the percent in parentheses represents the degree by which that specific cluster theoretically/potentially explains the given CPP | EPed has found many possible diseases that may explain the possible clusters found by EPed |

| Cough (“tuse”) | Systemic (biological) inflammatory syndrome (57%) | Tuberculosis (CSD = 1.1) |

| Fever (“febra”) | Systemic dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (42%) | Viral pneumonia (CSD = 1.1) |

| Wheezing (“wheezing”) | Broncho-esophageal fistula (42%) | Bacterial pneumonia (CSD = 1) |

| Increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (“VSH crescut”) | Tracheo-esophageal fistula (42%) | COVID-19 (CSD = 0.9) |

| Thrombocytopenia (“trombocitopenie”) | Bronchiolitis (a cluster defined by EPed as an inflammation of bronchioli) (28%) | Scarlet fever (CSD = 0.9) |

| Neutrophilia (“neutrofilie”) | Bronchiolitis obliterans (28%) | Acute viral diarrhea (CSD = 0.8) |

| Monocytosis (“monocitoza”) | Respiratory failure (28%) | Viral URTI (CSD = 0.8) |

| Pericarditis (28%) | Bronchiolitis (CSD = 0.6) | |

| Functional respiratory syndrome of obstructive type (28%) | Measles (CSD = 0.5) | |

| Dehydration (28%) | Influenza (CSD = 0.5) | |

| Pleurisy (28%) | Congenital broncho-esophageal fistula (disease) (CSD = 0.5) | |

| Alveolar pneumonia (28%) | Congenital tracheo-esophageal fistula (disease) (CSD = 0.5) | |

| Interstitial pneumonia (28%) | Bacterial URTI (CSD = 0.4) | |

| Bronchitis (14%) | Infectious mononucleosis with EBV or/and CMV (CSD = 0.4) | |

| Carditis (pancarditis) (14%) | Cystic fibrosis (CSD = 0.4) | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (14%) | Bacterial epiglottitis (CSD = 0.3) | |

| Rhinitis (a cluster defined by EPed as an inflammation of the nasal mucosa) (14%) | Viral laryngeal tracheitis (CSD = 0.2) | |

| Adenoiditis (a cluster defined by EPed as an inflammation of the nasal adenoids) (14%) | Periamygdalian abscess (phlegmon) (CSD = 0.2) | |

| Bacteremia (14%) | Cervical adenoflegmon (CSD = 0.2) | |

| Cholangitis (14%) | Asthma (CSD = 0.2) | |

| Endocarditis (14%) | Gastroesophageal reflux disease (CSD = 0.1) | |

| […] | Hiatal hernia (CSD = 0.1) | |

| Pyelonephritis (14%) | etc. | |

| Sepsis (14%) | ||

| Toxic bacterial syndrome (14%) | ||

| SIRS (14%) | ||

| CNS tuberculoma (14%) | ||

| Viremia (14%) | ||

| Hypersplenism (14%) | ||

| Vasculitis (14%) | ||

| etc. |

EPed is the first and only nml-AI KBS for "hybrid" (pediatric) physiopathological and disease medical diagnosis in Romania and worldwide. Although not a MES, EPed is very versatile.

The entire EPed prototype (including its unpacked database containing 302 clusters and 269 diseases) takes less than 3Mb on any USB memory stick or hard-disk, which makes it very practical, portable and RAM&ROM-memory efficient.

EPed is very efficient in its speed of input, because any CPS can be rapidly searched (even by using a word fragment!) in a pre-generated list of all CPSs from the database of EPed: In takes maximum 5 seconds to find any sign in the database, so that it takes about 30 seconds to input a set of 6 CPSs gathered from the patient, even in the emergency room.

EPed is very efficient in its speed of listing all the possible clusters and diseases, because it pre-loads its entire database in the RAM memory of any computer (with minimal RAM and ROM resources): In 2-3 seconds EPed identifies all possible clusters and diseases plus all the pseudo-probabilistic scores that serve in its 3 types of listings (by various scores or combination of scores).

The speed of input and computing of EPed is comparable to any online medical symptom checker. However, its focus on physiopathological clusters (by using a simple and robust nml-AI architecture), makes EPed much more versatile than any other symptom checker, because it intelligently and causally links CPSs to diseases not directly, but via clusters (which are causal medical concepts much more general and flexible than classical syndromes). The costs of periodically expanding and updating EPed (including its database) are exponentially lower than any medical AI diagnostic system, with EPed being much more energy-efficient than AI systems which are quite expensive and notorious for their huge energy expenditure and need for large human resources in their development. Furthermore, EPed doesn’t “hallucinate” as AI systems do. EPed can be also easily adapted in the future for Android phones/tablets and also for online use. EPed can be easily adapted and improved over time by using minimal human resource.

This prototype EPed was also preliminarily tested on real child-patients by comparing the EPed-proposed list of possible diseases with the list of all diagnoses of the child-patient at discharge (as established by a real MD)[15].

EPed may be used not only by students, interns and MD pediatricians but also by any other medical professional from any other (medical) specialty close to pediatrics (or interested in it): General practitioners, infectionists etc. EPed can also be regarded as a potential pedagogical tool usable in training future medical students and resident physicians by developing their physiopathological reasoning and differential diagnosis skills.

Many thanks (for all the encouragements and critical views!) to my Ph.D. supervisor, prof. dr. Roxana-Maria Nemeș, a well-known and very appreciated Romanian pneumologist, pediatrician and researcher.

| 1. | Sowa JF. Knowledge Representation: Logical, Philosophical, and Computational Foundations (1st ed.). Available from: https://books.google.ro/books/about/Knowledge_Representation.html?id=dohQAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y. |

| 2. | Lenert MC, Walsh CG, Miller RA. Discovering hidden knowledge through auditing clinical diagnostic knowledge bases. J Biomed Inform. 2018;84:75-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (101)] |

| 3. | O'Shea JS. Computer-assisted pediatric diagnosis. Am J Dis Child. 1975;129:199-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Johnson KB, Feldman MJ. Medical informatics and pediatrics. Decision-support systems. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:1371-1380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liang H, Tsui BY, Ni H, Valentim CCS, Baxter SL, Liu G, Cai W, Kermany DS, Sun X, Chen J, He L, Zhu J, Tian P, Shao H, Zheng L, Hou R, Hewett S, Li G, Liang P, Zang X, Zhang Z, Pan L, Cai H, Ling R, Li S, Cui Y, Tang S, Ye H, Huang X, He W, Liang W, Zhang Q, Jiang J, Yu W, Gao J, Ou W, Deng Y, Hou Q, Wang B, Yao C, Liang Y, Zhang S, Duan Y, Zhang R, Gibson S, Zhang CL, Li O, Zhang ED, Karin G, Nguyen N, Wu X, Wen C, Xu J, Xu W, Wang B, Wang W, Li J, Pizzato B, Bao C, Xiang D, He W, He S, Zhou Y, Haw W, Goldbaum M, Tremoulet A, Hsu CN, Carter H, Zhu L, Zhang K, Xia H. Evaluation and accurate diagnoses of pediatric diseases using artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25:433-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li YW, Liu F, Zhang TN, Xu F, Gao YC, Wu T. Artificial intelligence in pediatrics. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:358-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li Y, Zhang T, Yang Y, Gao Y. Artificial intelligence-aided decision support in paediatrics clinical diagnosis: development and future prospects. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520945141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jackson P. Introduction to Expert Systems (book, 3rd ed, 1998). Addison Wesley. Available from: https://books.google.ro/books/about/Introduction_to_Expert_Systems.html?id=9rJQAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y. |

| 10. | London S. DXplain: a Web-based diagnostic decision support system for medical students. Med Ref Serv Q. 1998;17:17-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Elkin PL, Liebow M, Bauer BA, Chaliki S, Wahner-Roedler D, Bundrick J, Lee M, Brown SH, Froehling D, Bailey K, Famiglietti K, Kim R, Hoffer E, Feldman M, Barnett GO. The introduction of a diagnostic decision support system (DXplain™) into the workflow of a teaching hospital service can decrease the cost of service for diagnostically challenging Diagnostic Related Groups (DRGs). Int J Med Inform. 2010;79:772-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Martinez-Franco AI, Sanchez-Mendiola M, Mazon-Ramirez JJ, Hernandez-Torres I, Rivero-Lopez C, Spicer T, Martinez-Gonzalez A. Diagnostic accuracy in Family Medicine residents using a clinical decision support system (DXplain): a randomized-controlled trial. Diagnosis (Berl). 2018;5:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bond WF, Schwartz LM, Weaver KR, Levick D, Giuliano M, Graber ML. Differential diagnosis generators: an evaluation of currently available computer programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:213-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Berner ES, Jackson JR, Algina J. Relationships among performance scores of four diagnostic decision support systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:208-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Drăgoi AL, Nemeș RM. The "Electronic Pediatrician (EPed®)" - A clinically tested prototype software for computer-assisted pathophysiologic diagnosis and treatment of ill children. Int J Med Inform. 2023;178:105169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |