Published online Sep 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.100459

Revised: January 13, 2025

Accepted: January 23, 2025

Published online: September 20, 2025

Processing time: 201 Days and 13.8 Hours

Systematic review focuses on the visual patient avatar (VPA) technology, a tool designed to enhance situational awareness in anesthesia by transforming tra

To explore how VPA can improve perceptual performance, reduce cognitive load, and increase user acceptance, potentially leading to better patient outcomes.

The review is based on 14 studies conducted between 2018 and 2023 in five different hospitals across Europe.

These studies demonstrate that VPA allows clinicians to perceive and recall vital signs more efficiently than conventional monitoring methods. The technology’s intuitive design helps reduce cognitive workload, indicating less mental effort required for patient monitoring. Users’ feedback on VPA was generally positive, highlighting its potential to enhance monitoring and decision-making in high-stress environments. However, some users noted the need for further develop

Review concludes that VPA technology represents a significant advancement in patient monitoring, promoting better situational awareness and potentially improving safety in perioperative care.

Core Tip: This systematic review examines the use of visual patient avatar technology to enhance perception, integration, and interpretation of medical data. Grounded in psychological and neuroscientific principles, the technology transforms information into intuitive shapes, colors, and animations, providing a clear advantage over traditional numerical formats. By simplifying complex data, it reduces cognitive workload, improves diagnostic accuracy, and bolsters clinical confidence. This innovative approach underscores the potential of visual representations in medical practice, fostering more efficient and effective decision-making processes for healthcare professionals.

- Citation: Tramontana A, Rulli M, Falegnami A, Bilotta F. Visual avatar to increase situational awareness in anaesthesia: Systematic review of recent evidence. World J Methodol 2025; 15(3): 100459

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i3/100459.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.100459

Visual patient avatar (VPA) is a computer derived representation of physiological variables that transforms traditional numerical data from patient monitors into intuitive visual displays using colors, shapes, and animations[1]. This tool can enhance situational awareness (SA), which is defined as the capacity to maintain an accurate internal representation of events in the environment and is considered an essential prerequisite for effective decision-making[2]. Innovation could allow anesthesiologist to quickly grasp patient conditions at a glance, improving, promoting and implementing their ability to monitor and respond to changes without constantly focusing on numerical displays and ultimately contribute to improve SA[1,2]. Over 80% of adverse events in anaesthesia stem from a deficiency in SA, with the first level of SA, as defined by Endsley, representing the largest proportion (42%). For instance, in the context of anaesthesia, this level involves recognizing the status and dynamics of the patient’s vital signs on the monitor[3]. Improving safety in anae

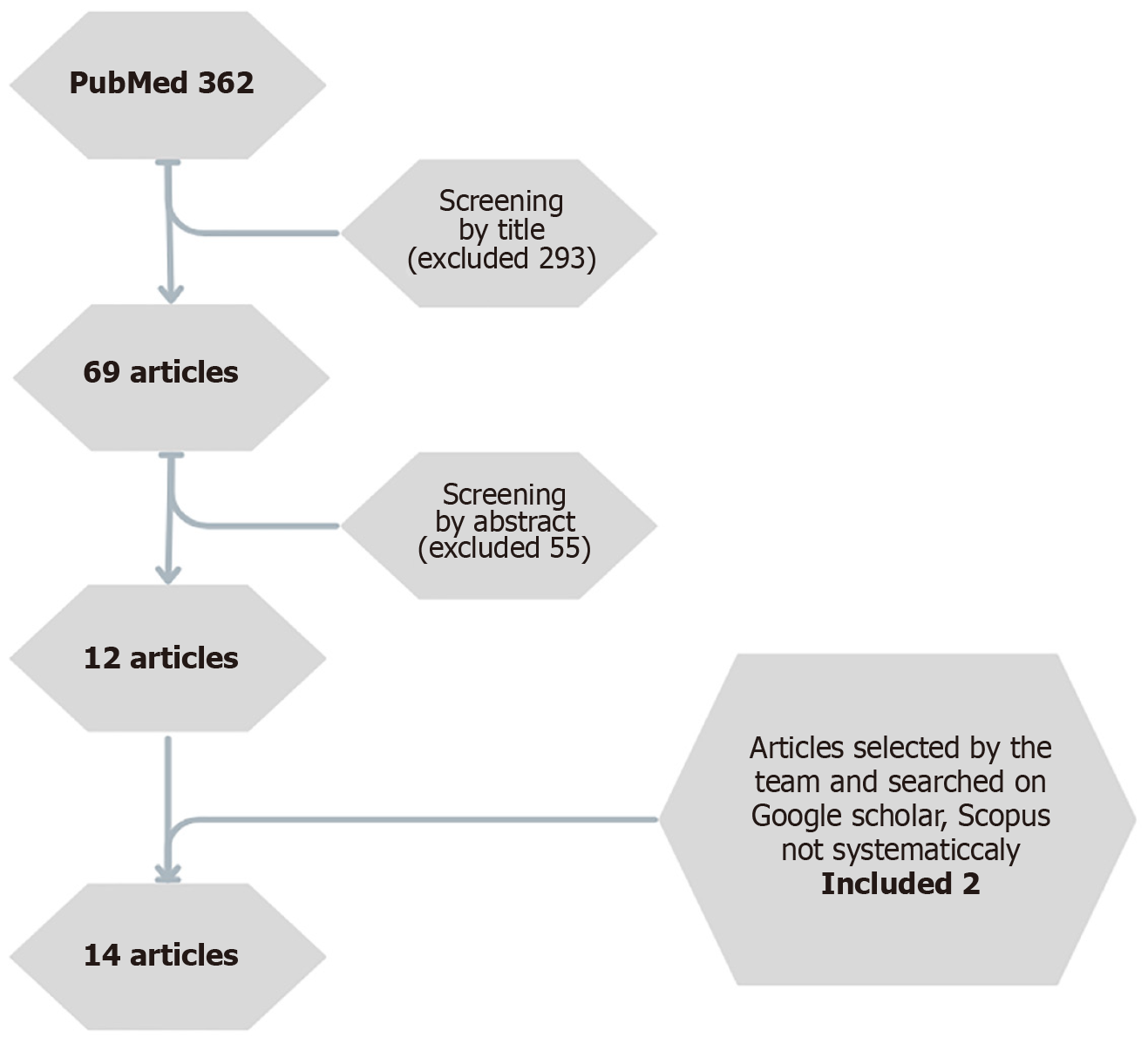

This systematic review is based on recent studies extracted by literature search in PubMed and retrieving selected evidence from Google scholar and Scopus. The PubMed for all types of articles using Medical Subject Headings terms, Boolean tools, and keywords for the topic of interest, such as “situational,” “situation”, “awareness,” “anesthesia” and “anaesthesia”, separately and in combination. All data were analyzed using a PRISMA 2009 checklist statement protocol as a guarantee of a complete and transparent data’s report. Full-text peer-reviewed randomized controlled trials, case-control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies and reviews that were published from January 1, 1975 to August 1, 2024, which investigated the updates of the VPA to improving, promoting and implementing their ability to monitor and respond to changes without constantly focusing on numerical displays were considered eligible. Articles published in languages other than English, animal studies, grey literature, and articles which do not include anaesthesia environment or adult patients were excluded. Literature search led to retrieve 362 articles screened by title, by abstract and by the full text (Figure 1). Out of these 12 articles were selected as eligible for this systematic review. At the end of this screening, also the literature on Scopus and Google scholar was searched to find related articles that were not spotted in PubMed.

A total of 14 articles were selected as appropriate for the present systematic review (Table 1). These studies address 3 principal aspects of the role of VPA in clinical practice: Perceptual performance, cognitive load, and user acceptance and integration. These prospective studies were conducted between December 2018 and December 2023 in five different hospitals across Switzerland[5-18], Germany[6,7,9], and Spain[6,7,9]. The participants consisted of volunteer medical staff, including anesthesiologists and nurses. Approximately 50% of the participants were women, with ages ranging from 30 years to 37 years and work experience spanning approximately 4 years to 8 years[5-18]. As this was the first time implementing this VPA in simulated practice using various technologies, the researchers deemed it necessary to conduct preliminary educational sessions, followed by off-site training. Furthermore, a video and reference materials were provided to each physician via the hospital’s intranet[5-7,9,15-18]. VPA technology is capable of displaying various parameters, including pulse rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, electrocardiogram ST-segment, central venous pressure, respiratory rate, tidal volume, expiratory carbon dioxide concentration, body temperature, brain activity, and neuromuscular relaxation[5].

Data were collected using an open questionnaire and a quiz administered via iSurvey on an iPad (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, United Sates). The data obtained were analyzed using a six-phase thematic analysis for the open-ended responses, employing the Harvest Your Data tool (Wellington, New Zealand)[5,6]. The quiz and demographic data were processed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation), and translations were facilitated by DeepL (DeepL SE, Cologne, Germany)[5,6,15]. Some studies also utilized eye-tracking technology, such as the Gazepoint GP3 (Gazept, Vancouver, BC, Canada)[10,14,18] or the Pupil Invisible mobile eye-tracking device (Pupil Labs GmbH)[10], to assess clinicians’ ability to retrieve and remember data. The resulting data provided enhanced insights into the underlying analytical pathways by offering information on spatial and temporal measurements, gaze coordinates, dwell times on areas of interest (AOI), as well as saccades and fixations. These data were analyzed using Gazepoint Professional Analysis software (Gazept, Vancouver, BC, Canada) or Pupil Player for eye-tracking data analysis (Pupil Labs GmbH)[6,10,14,18]. Additionally, some tests were conducted using a Google Glass headset (Alphabet Inc.)[18]. In all the referenced papers, tests were conducted to evaluate the participants’ ability to rapidly comprehend situations and process additional information presented on a visual avatar monitor compared to a standard monitor[5-18]. The results demonstrated statistical significance, with a P value of < 0.05[6,9].

In 13 of 14 articles are reported evidenced related to the impact of implementing in clinical practice VPA on Perceptual Performance[5-10,12-18]. The thirteen articles reviewed claim that the VPA exhibits favorable usability characteristics, including rapid identification of underlying problems, excellent visibility of vital parameters from a distance, and valuable additional support, especially for beginners, compared to traditional displays. Participants also appreciated the appealing graphic design of the VPA and emphasized its intuitive nature[5-10,12-18]. Participants were required to categorize data as “too low”, “too high”, or “normal” and remember the placement and location of installations in a patient[5,6]. The distribution of fixations and dwell time did not show statistically significant differences between the screen modes (avatar-only vs conventional monitor and split-screen). The monitoring modes also did not reveal significant differences in fixation and dwell time concerning variables such as profession, work experience, and scenario sequence.

The scenarios significantly influenced fixation and dwell time on the monitor, with participants showing greater attention during the myocardial infarction scenario. Better task performance was associated with a reduction in fixations and dwell time on the monitor, suggesting an inverse relationship between performance efficiency and the visual attention required. Participants had fewer fixations and spent less time on the avatar portion of the screen compared to the conventional part, indicating a difference in the mode of visualization[10]. In conventional monitoring, the time spent on AOIs for installations ranged from 2.13 seconds to 2.51 seconds, while for VPA-intensive care unit, the time distribution was more balanced, with no AOI viewed for an excessively long time[6].

Analysis of variance tests for time spent on alarms across cases indicated no statistically significant differences (P = 0.193). However, a greater amount of time was spent on alarms in instances involving yellow and red alerts (P = 0.018, moderate evidence). In conventional monitoring, more time was spent on installation areas, while the VPA exhibited a more balanced distribution of time across AOIs[6]. Other studies emphasize the need for further development of the VPA monitor into a subsequent model, known as VPA-intensive care unit, incorporating features identified by users in previous studies as essential[9]. Among the most notable features that need further improvements are: Enhancements in graphic design, improved accuracy in presenting displayed information, refinements in system-user interface[9].

The typically displayed information includes the following parameters: Pulse contour cardiac output catheter, intracranial pressur sensor, neuromuscular relaxation, central venous line, ST segment, arterial line, urinary catheter, peripheral venous line, tube functionality, brain activity, etCO2, brain activity sensor, central venous pressure, temperature, peak inspiratory pressure, SpO2, FiO2, respiratory rate, cardiac index, electrocardiogram/pulse rate, tidal volume, and mean arterial blood pressure[6,9]. Controlled studies show that anesthesia providers using VPA technology were able to perceive and recall more vital signs correctly compared to traditional monitoring methods. For instance, in 10-second scenarios, providers identified a median of 11 vital signs using the avatar, compared to 7 with conventional monitors, indicating that the avatar-based system allows for more efficient information processing in high-pressure situations[5].

The study established the hypothesis that split-screen monitoring is non-inferior to conventional monitoring in terms of performance on critical tasks during anesthesia emergency scenarios. Furthermore, the use of the avatar enhanced the likelihood of verbalizing the cause of the emergency compared to conventional monitoring. The results indicate that this technology can serve as a safe and situational-awareness-focused supplement to conventional monitoring. However, the user’s greater familiarity with conventional monitoring, as opposed to their limited experience with the avatar, may act as a significant confounding factor, potentially underestimating the true impact of the avatar[9,10].

In one study was used the Paced Auditory Serial Addition test, the test, which involves arithmetic tasks, simulates distraction by requiring participants to listen to and sum up numbers presented every 2 seconds[16]. This task necessitates various cognitive resources and ensures identical test conditions for all participants, evidenced no significant difference between the two types of monitoring and viewing times[16].

In 13 of 14 articles are reported evidenced related to the impact of implementing in clinical practice VPA on cognitive load[5-10,12-18]. The second chapter delves into the capacity of this technology to reduce cognitive load, a topic of significant interest within the scientific community. Notably, this technology has demonstrated a reduction in perceived workload among anesthesia providers. In one study, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index, a recognized measure of cognitive workload, was significantly lower when using avatar-based monitoring compared to traditional methods. This finding suggests that the VPA can help alleviate the mental effort required to monitor patients, potentially leading to fewer errors and faster decision-making[5-10,12-18]. It is important to note that, with the advancement of technology, the increasing volume of data necessitates complex systems for integration and visualization to effectively reduce cognitive load[5]. In fact, 80% of errors during perioperative treatment are attributed to reduced SA caused by cognitive overload[5]. Avatar-based monitoring reduces perceived workload, particularly when the duration of monitor observation is brief[15,16].

In 7 of 14 articles are reported evidenced related to the impact of implementing in clinical practice VPA on perceptual performance[8,11,13,14,16-18]. Following the implementation of the VPA in clinical settings, anesthesia providers reported that it significantly enhanced their ability to monitor patients and make timely decisions, thanks to the quick overview and rapid problem identification facilitated by the avatar technology. Despite some initial resistance and the need for adjustments to accommodate individual preferences, the overall reception was positive, suggesting a high potential for broader adoption in clinical practice[8,11,13,14,16-18].

The limitations of the VPA include the need for further development to enhance visualization designs, particularly by implementing user-customizable thresholds or aligning them with predefined audible alarm limits. The potential solutions suggested by study participants, such as improvements in visualization design, should be further explored and refined to enhance the effectiveness and usability of the VPA[11,13,14]. Additionally, due to the data integration involved, there are instances where accurately conveying the situation can be challenging because of data volume reduction. These efforts have sparked a new interest not only in advancing scientific knowledge but also in integrating these advancements into clinical practice. To monitor user acceptance, significant attention has been devoted to reflexivity, which in these studies is categorized into personal, methodological, and contextual reflexivity[8,18].

Positive feedback focused on the design, intuitiveness, time-saving features, and clarity in visualizing patient devices. Negative feedback included concerns about sensory overload, the need for more familiarity, and incomplete information. Key areas for improvement included usability, visibility, and the need for customizable alarm thresholds. Further development is necessary to enhance the effectiveness and usability of the VPA, particularly in its visualization designs and data integration[8,16].

This systematic review originally summarizes recent evidence related to simulate training of VPA in anesthesia to promote SA, which demonstrates that implementing VPA technology in anesthesia can enhance perceptual performance, reduce cognitive load, and increase user acceptance, thereby improving the safety and effectiveness of anaesthetic practices. As a matter of fact, 80% of participants reported that distractions occur frequently during their daily work in the operating theatre[8,11,13,14,16,18].

SA consists of three stages: Perception, comprehension, and projection, and is crucial for informed decision-making[14,18]. Many technological advances use and implement the SA’s stages to significantly improve patient care in perioperative and critical settings[5]. According to cognitive load theory, humans are incapable of processing massive amounts of data for long periods of time due to the limited capacity of working memory. Working memory can usually manage 5 items to 9 items at a time. Typically manages between 5 items and 9 items at a time. When working memory is over

Dual-processing theory established that human thinking and visual information processing are divided into two complementary systems: The associative system (System 1) and the reasoning system (System 2). System 1 enables rapid, instinctive decision-making that does not rely on working memory and is primarily influenced by emotions and intuitive judgments. In contrast, System 2 governs slower, more deliberate, and rational decision, predominantly regulated by the frontal cortex. These two systems operate concurrently, integrating to form a cohesive perception of visual information. However, current state-of-the-art monitors that rely on waveforms are not optimized to support quick and confident interpretation with minimal cognitive effort[9].

So, human brain is capable of rapidly detecting color, motion, and shape, seamlessly integrating this information to form associations. These principles can provide a foundation for designing user-centered patient monitoring technologies that enhance SA and optimize sensory perception. In contrast, the traditional single-sensor, single-indicator model, which presents information in isolation, may impose a greater cognitive burden on the user[8].

Several distinctive features of conventional representation contribute to this issue: Individuals can only process numbers sequentially; the displayed numbers represent low-level data that is only indirectly relevant to the task; many of the numbers shown fall within similar ranges (e.g., pulse rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation); and individuals can retain only 7 digits, plus or minus 2, in their short-term memory at a time[18]. Conversely, the human brain can rapidly detect color, motion, and shape, integrating these cues to form associations. These principles can inform the design of user-centered patient monitoring technologies that enhance SA and optimize sensory perception, such as the VPA evaluated in these studies[8]. Comparing the results of this review on Philips VPA with previous research is possible to demonstrate that visualization technologies improve clinicians’ SA, diagnostic confidence, and reduce workload, but is possible to demonstrate, also, the limitations of these studies. In fact, there are other examples of technologies of visualization in the literature that are not included in these studies (Table 2).

| Name | Company | Characteristics |

| Alert Watch | AlertWatch, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, United States | Multifunction decision - supporting systems for intraoperative anesthetic care, obstetric care, and remote monitoring |

| Dynamic lung | Hamilton Medical AG, Bonaduz, Switzerland | Respiratory monitoring data from ventilators in an animated anatomical lung image |

| Hemo-sight | Mindray Medical International Limited, Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China | Advanced hemodynamic monitoring |

| Pulmo-sight | Mindray Medical International Limited, Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China | Anatomical lung image with a bronchial tree and trachea to visualize respiratory parameters |

| Physiology screen | Edwards Lifesciences Corp., Irvine, CA, United States | Advanced hemodynamic monitoring |

| Alarm status visualizer | Masimo Corp., Irvine, CA, United States | Colored-visual alarm indicators on a three - dimensional anatomical image |

| ROTEM sigma | Werfen Inc., Barcelona, Spain | Graphical and visual interpretation of rotational thromboelastometry |

| Visual blood | University of Zurich, Switzerland | Visualization of arterial blood gas analyses |

Literature search did not include databases other than PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, which might have excluded relevant studies published elsewhere. However, the final article selection was carefully made, offering a balanced representation of the evidence. Most studies were conducted in controlled simulated environments, which may limit the applicability of the results to real clinical settings or other specialties. The participant group was voluntary and non-randomized, and some studies had a significant amount of missing data. Even though, the implications for clinical practice are significant. VPA technology represents a major advancement in patient monitoring, providing a more intuitive and effective way for clinicians to maintain SA and manage cognitive load during critical procedures, but not one of these studies has been done during clinical practice. Even though, the evidence suggests that adopting this technology can improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce clinical errors, and increase user satisfaction, indicating a high potential for broader integration into clinical practice. Maybe for now, as a safe addition to patient monitoring could be consider implementing a combination of avatar and conventional monitoring in a split-screen layout.

The chapter on integration and user acceptance was, in our opinion, the most interesting and original, as it has sparked less debate within the scientific community. We place significant importance on this chapter due to our team’s longstanding interest in and sensitivity to the ergonomics and clinical integration of new technologies in anesthesia. Additionally, as highlighted in studies on the “cockpit” environment, the rapid integration and acceptance by clinical operators underscore the importance of ergonomics and usability of new technologies in healthcare settings. Future studies, appropriately design, should evaluate the impact in clinical practice. The present review can design the future research protocol.

This systematic review on the VPA technology facilitates perception, integration, and interpretation, according to psychological and neuroscientific foundations, integrated the information in shapes, colors, and animations, compared to traditional formats like numbers, reducing workload and enhancing diagnostic confidence. The technology is not only straightforward to learn but also proves particularly valuable in high-cognitive load environments, where it enhances SA and supports swift, accurate decision-making. In fact, Eye-tracking studies affirm that the design of visual patient enhances visual perception, enabling users to process vital information more effectively across their entire visual field. This comprehensive approach ensures that critical data is conveyed with clarity and speed, making it an invaluable tool in clinical settings where time and precision are of the essence. In conclusion, presented results suggest a promising role of VPA in improving SA ultimately leading to increased perioperative safety.

| 1. | Gaba DM, Howard SK, Small SD. Situation awareness in anesthesiology. Hum Factors. 1995;37:20-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Weller JM, Mahajan R, Fahey-Williams K, Webster CS. Teamwork matters: team situation awareness to build high-performing healthcare teams, a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2024;132:771-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 3. | Endsley MR. Designing for Situation Awareness. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2004. |

| 4. | Neves S, Soto RG. Distraction in the OR: Bells and Whistles on Silent Mode. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2019;57:62-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hunn CA, Lunkiewicz J, Noethiger CB, Tscholl DW, Gasciauskaite G. Qualitative Exploration of Anesthesia Providers' Perceptions Regarding Philips Visual Patient Avatar in Clinical Practice. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024;11:323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 6. | Viautour J, Naegeli L, Braun J, Bergauer L, Roche TR, Tscholl DW, Akbas S. The Visual Patient Avatar ICU Facilitates Information Transfer of Written Information by Visualization: A Multicenter Comparative Eye-Tracking Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:3432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 7. | Lunkiewicz J, Gasciauskaite G, Roche TR, Akbas S, Nöthiger CB, Ganter MT, Meybohm P, Hottenrott S, Zacharowski K, Raimann FJ, Rivas E, López-Baamonde M, Beller EA, Tscholl DW, Bergauer L. User Perceptions of Avatar-Based Patient Monitoring for Intensive Care Units: An International Exploratory Sequential Mixed-Methods Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:3391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 8. | Gasciauskaite G, Lunkiewicz J, Roche TR, Spahn DR, Nöthiger CB, Tscholl DW. Human-centered visualization technologies for patient monitoring are the future: a narrative review. Crit Care. 2023;27:254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 9. | Bergauer L, Braun J, Roche TR, Meybohm P, Hottenrott S, Zacharowski K, Raimann FJ, Rivas E, López-Baamonde M, Ganter MT, Nöthiger CB, Spahn DR, Tscholl DW, Akbas S. Avatar-based patient monitoring improves information transfer, diagnostic confidence and reduces perceived workload in intensive care units: computer-based, multicentre comparison study. Sci Rep. 2023;13:5908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ljubenovic A, Said S, Braun J, Grande B, Kolbe M, Spahn DR, Nöthiger CB, Tscholl DW, Roche TR. Visual Attention of Anesthesia Providers in Simulated Anesthesia Emergencies Using Conventional Number-Based and Avatar-Based Patient Monitoring: Prospective Eye-Tracking Study. JMIR Serious Games. 2022;10:e35642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wetli DJ, Bergauer L, Nöthiger CB, Roche TR, Spahn DR, Tscholl DW, Said S. Improving Visual-Patient-Avatar Design Prior to Its Clinical Release: A Mixed Qualitative and Quantitative Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Roche TR, Said S, Braun J, Maas EJC, Machado C, Grande B, Kolbe M, Spahn DR, Nöthiger CB, Tscholl DW. Avatar-based patient monitoring in critical anaesthesia events: a randomised high-fidelity simulation study. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:1046-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tscholl DW, Rössler J, Said S, Kaserer A, Spahn DR, Nöthiger CB. Situation Awareness-Oriented Patient Monitoring with Visual Patient Technology: A Qualitative Review of the Primary Research. Sensors (Basel). 2020;20:2112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tscholl DW, Rössler J, Handschin L, Seifert B, Spahn DR, Nöthiger CB. The Mechanisms Responsible for Improved Information Transfer in Avatar-Based Patient Monitoring: Multicenter Comparative Eye-Tracking Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e15070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Garot O, Rössler J, Pfarr J, Ganter MT, Spahn DR, Nöthiger CB, Tscholl DW. Avatar-based versus conventional vital sign display in a central monitor for monitoring multiple patients: a multicenter computer-based laboratory study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pfarr J, Ganter MT, Spahn DR, Noethiger CB, Tscholl DW. Effects of a standardized distraction on caregivers' perceptive performance with avatar-based and conventional patient monitoring: a multicenter comparative study. J Clin Monit Comput. 2020;34:1369-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tscholl DW, Handschin L, Neubauer P, Weiss M, Seifert B, Spahn DR, Noethiger CB. Using an animated patient avatar to improve perception of vital sign information by anaesthesia professionals. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:662-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pfarr J, Ganter MT, Spahn DR, Noethiger CB, Tscholl DW. Avatar-Based Patient Monitoring With Peripheral Vision: A Multicenter Comparative Eye-Tracking Study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e13041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |