Published online Mar 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i1.95985

Revised: August 7, 2024

Accepted: August 13, 2024

Published online: March 20, 2025

Processing time: 158 Days and 6.7 Hours

The benefits of regular physical activity are well known. Yet, few studies have examined the effectiveness of integrating physical activity (PA) into curricula within a post-secondary setting. To investigate the incorporation of PA into medical curriculum, we developed a series of optional exercise-based review sessions designed to reinforce musculoskeletal (MSK) anatomy course material. These synchronous sessions were co-taught by a group fitness instructor and an anatomy instructor. The fitness instructor would lead students through both strength and yoga style exercises, while the anatomy instructor asked questions about relevant anatomical structures related to course material previously covered. After the sessions, participants were asked to evaluate the classes on their self-reported exam preparedness in improving MSK anatomy knowledge, PA levels, and mental wellbeing. Thirty participants completed surveys; a majority agreed that the classes increased understanding of MSK concepts (90.0%) and activity levels (97.7%). Many (70.0%) felt that the classes helped reduce stress. The majority of respondents (90.0%) agreed that the classes contributed to increased feelings of social connectedness. Overall, medical students saw benefit in PA based interventions to supplement MSK course concepts. Along with increasing activity levels and promoting health behaviours, integrating PA into medical curriculum may improve comprehension of learning material, alleviate stress and foster social connectivity among medical students.

Core Tip: There is a paucity of evidence on the integration of physical activity (PA) with post-secondary curricula. The current study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of exercise-based review sessions in reinforcing musculoskeletal (MSK) anatomy course content. It was found that overall, medical students saw benefit in PA based interventions to increase understanding of MSK concepts, reduce stress and increase activity levels. Therefore, integrating PA into medical curricula may not only supplement learning, but also promote healthy behaviour and supplement both physical and mental wellbeing.

- Citation: Samarasinghe NR, Nagpal TS, Barbeau ML, Martin CM. Getting physical with medical education: Exercise based virtual anatomy review classes for medical students. World J Methodol 2025; 15(1): 95985

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i1/95985.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i1.95985

It is well-established that leading an active lifestyle is associated with physical and mental health benefits. Learning environments can promote movement behaviours through integrating physical activity into curricula[1]. Several studies have demonstrated successful strategies to encourage movement through integration of activity into core curriculum, such as mathematics and literature, which have also resulted in improved overall academic performance[1,2]. Most of the work advocating for active curricula has focused on younger learners, but these findings could extend to older student populations as well. Medical students, in particular, are at an increased risk of excessive sedentary behaviour and do not meet physical activity guidelines, spending a significant amount of time seated in academic settings[3].

The incorporation of physical activity (PA) learning strategies integrated with curricular content may encourage movement behaviours among medical students while simultaneously reinforcing related course concepts. This integration of learning strategies is supported by the Experiential Learning Theory, which when effectively integrated the learner is able to construct knowledge and meaning from real-life experiences[4,5]. The fundamental subject of anatomy is an opportune area to introduce exercise-based content delivery in medical curricula as certain anatomical concepts can be reinforced with movement and practical application. Bentley and Pang[6], developed a learning session that guided yoga practitioners through five yoga poses while simultaneously discussing the related bones and muscles of the lower extremity. After the session, 76.4% of the participants were able to apply the anatomical information they learned to their yoga practice. Similarly, McCulloch et al[7] found that integrating yoga and Pilates with anatomical instruction resulted in medical students increasing their anatomy comprehension, physical awareness, and relaxation and well-being.

The goal of this innovation was to develop a series of exercise-based review classes, that integrate musculoskeletal (MSK) curricular concepts to aid in preparation for anatomy examinations. We also aimed to explore the perceptions of participating undergraduate medical students to evaluate the impact of these physical activity-based review sessions on self-reported exam preparedness, activity levels, mental wellbeing, and social connectedness.

Three exercise-based review sessions were developed by a medical student certified as a healthy adult group fitness instructor in collaboration with anatomy instructors. Two sessions were circuit strength style sessions and the third was a yoga inspired session. All sessions targeted the entire body. Each circuit consisted of three exercises, which were performed twice. Each exercise, within the circuit, was timed or performed for 15 repetitions. During each session, students were guided through exercises by the instructor while the professor questioned them and discussed relevant MSK anatomical concepts. For example, one circuit consisted of squats, Romanian deadlifts, and standing lateral leg raise. During squats, the fitness instructor would cue a squat while describing the correct form and then when the students were performing their repetitions, the anatomy instructor would ask questions such as, which muscle is the prime mover, what type of contraction is the muscle performing, origins, insertions, and innervations. The yoga-style session allowed for a deeper dive into joint structures and the anatomy instructor questioned the students on passive and dynamic stabilizers of the joints being used during each pose. Examples of exercises and corresponding anatomy cues are outlined in Table 1.

| Class format | Exercise | Anatomy cues | ||

| Bodyweight resistance exercise | Reverse lunge | Muscle: This exercise should be felt in the quadriceps, but what other muscle groups are being activated? | ||

| Also working gluteal region, the hamstring group, and the medial compartment of thigh | ||||

| What are the three muscles that form the ‘glutes’? | ||||

| Gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus | ||||

| Innervation: What are they innervated by? | ||||

| Gluteus maximus: Inferior gluteal nerve | ||||

| Gluteus medius and minimus: Superior gluteal nerve | ||||

| Clinical correlate: What can result if gluteus medius and minimus lose their innervation? | ||||

| Trendelenburg gait/sign | ||||

| Bodyweight resistance exercise | Push ups | Muscle: What muscles are being used when performing this exercise? | ||

| Pectoralis and triceps muscle group | ||||

| Origin/ Insertion: Where do these muscles originate from and where do they insert? | ||||

| Pectoralis: Originates from the midline (sternum and clavicle) to attach at the humerus (pec. major) and coracoid process of scapula (pec. minor) | ||||

| Triceps: Originate on humerus and cross elbow joint to insert on olecranon process of ulna | ||||

| Exception: long head of triceps which originates from the infraglenoid tubercle of scapula and is the only one to cross the shoulder joint | ||||

| Innervation: What are they innervated by? | ||||

| Medial and lateral pectoral nerve (pectoralis) | ||||

| Radial nerve (triceps) | ||||

| Yoga | Warrior two | Muscle: What muscles are holding the arms up in abduction? | ||

| Deltoid and supraspinatus (first 15 degrees of abduction) | ||||

| Innervation: What nerves are they innervated by and what are the nerve roots: | ||||

| Deltoid: Axillary nerve | ||||

| Supraspinatus: Suprascapular nerve | ||||

| Roots: C5 and C6 | ||||

| Clinical correlate: What would be the result of a C5, C6 nerve root lesion? | ||||

| Waiter's tip position: Adduction, medial rotation, extension and pronation of arm | ||||

Second year medical students at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University were provided the opportunity to take part in optional exercise-based review sessions during their MSK block prior to their MSK anatomy examinations. In the first year, the review sessions were offered in-person, in a gym setting with weights. During the second offering, the exercises were modified to body-weight only exercises as the review sessions were offered online via Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, United States). The optional exercise review sessions were dispersed over a two-week period and were held following the completion of MSK anatomy coursework, including didactic lectures and laboratory sessions.

Exercise-based review session participants were invited to participate in a voluntary Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, United States) survey after the sessions were complete. To determine participants’ perceived physical activity levels, we asked students to indicate whether they were meeting Canadian adult physical activity guidelines of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week, if they normally noticed a change in their activity levels during exam times, and to rate the sessions on their effectiveness in improving activity levels[8]. To determine participants’ perceptions about the sessions as an MSK study tool, we asked participants to rate the classes on their effectiveness in enhancing understanding of MSK concepts. To determine participants’ perceptions about the sessions’ impact on their mental well-being, par

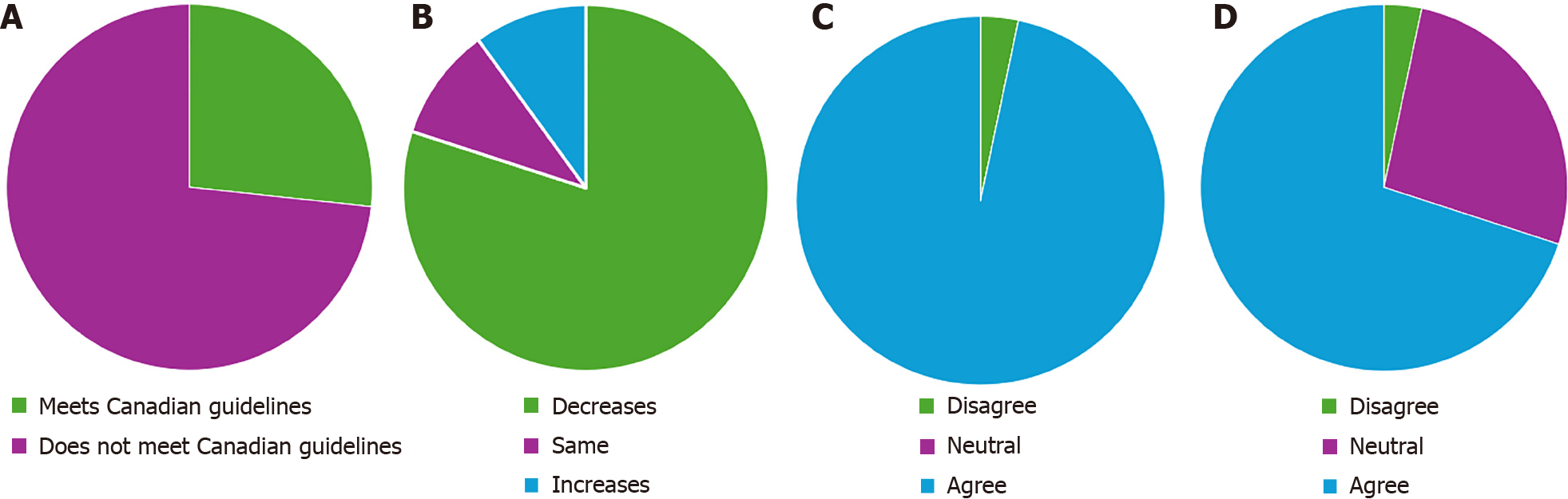

Thirty participants completed the surveys, of those, 13 participants (43.3%) attended only the virtual sessions; four (13.3%) attended only the in-person sessions; 13 (43.3%) attended both the in-person and virtual sessions. Of the 13 participants who had experience with both session formats (virtual and in-person), nine indicated a preference for in-person sessions (30.0%), one indicated equal preference for both (3.3%), while the remaining (n = 11, 10.0%) did not have a preference. Almost three quarters of participants (73.3%) reported that they did not regularly meet the recommended activity levels outlined in the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. Ninety percent of participants (n = 27) agreed that the exercise-based review classes increased their understanding of MSK concepts and helped with exam preparation (90.0%, n = 27). Most participants (96.6%, n = 29) agreed that the classes helped increase their activity level, while 70.0% (n = 21) reported agreement that the classes helped reduce their stress level (Figure 1). Ninety percent of participants (n = 27) agreed that the classes increased social connection among their peers. All participants (100%, n = 30) agreed that the classes were enjoyable and they would consider attending similar classes in the future. All items and frequency of responses are presented in Table 2.

| Survey item | Participant response (n = 30) | ||

| Activity level | Meets Canadian guidelines | Does not meet Canadian guidelines | |

| 8 (26.7) | 22 (73.3) | ||

| Change in activity level during exams | Decreases | Stays the same | Increases |

| 24 (80.0) | 3 (10.0) | 3 (10.0) | |

| Confidence in incorporating exercise counselling in your future practice | Not confident at all/Not very confident | Somewhat confident | Extremely confident/Very confident |

| 7 (23.3) | 18 (60.0) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Feedback on class participation and understanding of MSK concepts | |||

| Disagree | Neutral | Agree | |

| Participating improved my understanding of MSK course concepts | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.0) | 27 (90.0) |

| Classes helped me feel prepared for my MSK assessments | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.0) | 27 (90.0) |

| I feel more confident integrating MSK concepts in my future practice and daily physical activity | 2 (6.7) | 3 (10.0) | 25 (83.3) |

| Feedback on class participation and change in physical activity behaviours | |||

| Disagree | Neutral | Agree | |

| Attending class helped increase my activity level during exam period | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (96.7) |

| Attending class helped increase my motivation to be physically active | 1 (3.3) | 3 (10.0) | 26 (86.7) |

| I am more likely to try different exercise modalities after attending class | 3 (10.0) | 8 (26.7) | 19 (63.3) |

| Feedback on class participation and stress related to exams and pandemic response | |||

| Disagree | Neutral | Agree | |

| Attending classes helped reduce stress during exam period | 1 (3.3) | 8 (26.7) | 21 (70.0) |

| Attending classes helped with feeling connected to my classmates | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.0) | 27 (90.0) |

| Overall I enjoyed attending class | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (100.0) |

| I would consider attending similar classes in the future | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (100.0) |

Students who participated in online and in-person exercise sessions to review MSK concepts provided positive feedback, and overall, suggested that this is an effective way to increase activity levels and improve their perceived comprehension of course concepts. Our findings align with previous work, which found that the incorporation of exercise activities increased anatomy knowledge comprehension[6,7]. Previous work has attributed the combination of non-traditional learning environments and hands-on activities to the effectiveness of these interventions[7]. In particular, Kolb’s Theory of Experiential Learning offers an explanation to the success of activity-based learning sessions. This theory centres on a process where learners first grasp new knowledge and then transform that knowledge by applying it to their own experiences. Learning is described as a dynamic cycle comprised of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation[9]. Applying these concepts to our exercise-based review classes, students were first able to develop a concrete understanding of MSK anatomy through lectures and asynchronous content. Next, they reflected on the content and developed a conceptual framework during their in-person or virtual laboratories and through Socratic questioning of the anatomy concepts by their professors and teaching assistants during the sessions. Finally, during the exercise-based reviews, learners actively translated this knowledge and applied their understanding of nerve supply, muscles, and joints to movement of their own bodies. Thus, integration of exercise-based learning opportunities may be an effective way to implement active experimentation of anatomical knowledge.

Almost three quarters of participants (73.3%) reported that they did not regularly meet the recommended activity levels outlined in the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. This percentage increased through examination periods, with 80.0% of respondents reporting decreased activity levels during these times. These findings are similar to those reported by Blake et al[10] who, in a survey of medical students at a United Kingdom institution, found that most medical students did not meet physical activity guidelines, citing lack of time with study or placement schedules as perceived barriers to exercise. Incorporating physical activity into curricula could serve as a means to overcome these barriers and lead to change in physical activity behaviours of medical students. This is shown by our survey as 96.6% of participants reported that the exercise-based sessions helped to increase their physical activity levels during exams and 86.7% indicated an increased motivation to be physically active.

Decreased exercise is implicated in higher rates of depression and burnout among medical students, whereas increased physical activity is associated with enhanced coping mechanisms and overall mental well-being[11]. This was reflected in our findings, with 70.0% of participants endorsing that exercise-based learning helped reduce stress during examination their period. Similarly, 90.0% of respondents attributed class participation with an increased sense of connection to their classmates. As many medical programs are shifting to asynchronous delivery of content, the incorporation of exercise-based learning activities may help to foster community and build social connections between classmates in a more isolated learning environment.

Promoting exercise among medical students is especially important when considering their role in health advocacy as future physicians. It has been shown that personal physical activity practices of physicians influences their attitudes and recommendations of physical activity in clinical settings, resulting in active physicians providing more exercise counselling to their patients[12]. Incorporation of exercise-based learning sessions into medical curricula can enhance basic science knowledge and increase understanding of lifestyle medicine practices, which may lead to an increase in medical students’ confidence in counselling patients in exercise-based preventative medicine.

In conclusion, undergraduate medical students perceived exercise-based review sessions to be enjoyable, and found they increased their knowledge of core MSK concepts and exam preparedness. Additionally, integration of group physical activity into medical curricula can increase learner activity levels, which may result in alleviation of stress and promotion of socialization among students. Ideally exercise-based sessions should be integrated into the formal curriculum so all students benefit from the application of knowledge and review.

| 1. | Watson A, Timperio A, Brown H, Best K, Hesketh KD. Effect of classroom-based physical activity interventions on academic and physical activity outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Egger F, Benzing V, Conzelmann A, Schmidt M. Boost your brain, while having a break! The effects of long-term cognitively engaging physical activity breaks on children's executive functions and academic achievement. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fan LM, Collins A, Geng L, Li JM. Impact of unhealthy lifestyle on cardiorespiratory fitness and heart rate recovery of medical science students. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kolb DA. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall; 1984. |

| 5. | Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: transforming theory into practice. Med Teach. 2012;34:161-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bentley DC, Pang SC. Yoga asanas as an effective form of experiential learning when teaching musculoskeletal anatomy of the lower limb. Anat Sci Educ. 2012;5:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McCulloch C, Marango SP, Friedman ES, Laitman JT. Living AnatoME: Teaching and learning musculoskeletal anatomy through yoga and pilates. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3:279-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology. 24-Hour Movement Guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology. 2021 [cited September 18, 2023]. Available from: https://csepguidelines.ca/guidelines/adults-18-64/. |

| 9. | Kolb AY, Kolb DA. Experiential Learning Theory as a Guide for Experiential Educators in Higher Education. ELTHE. 2017;1:38. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Blake H, Stanulewicz N, Mcgill F. Predictors of physical activity and barriers to exercise in nursing and medical students. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73:917-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wolf MR, Rosenstock JB. Inadequate Sleep and Exercise Associated with Burnout and Depression Among Medical Students. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:174-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lobelo F, Duperly J, Frank E. Physical activity habits of doctors and medical students influence their counselling practices. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:89-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |