Published online Sep 20, 2024. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v14.i3.92932

Revised: April 24, 2024

Accepted: May 7, 2024

Published online: September 20, 2024

Processing time: 134 Days and 5.8 Hours

Violence against healthcare workers (HCWs) in the Caribbean continues to prevail yet remains underreported. Our aim is to determine the cause, traits, and consequences of violence on HCWs in the Caribbean.

To determine the cause, traits, and consequences of violence on HCWs in the Caribbean.

This research adopted an online cross-sectional survey approach, spanning over eight weeks (between June 6th and August 9th, 2022). The survey was generated using Research Electronic Data Capture forms and followed a snow

The survey was completed by 225 HCWs. Females comprised 61%. Over 51% of respondents belonged to the 21 to 35 age group. Dominica (n = 61), Haiti (n = 50), and Grenada (n = 31) had the most responses. Most HCWs (49%) worked for government academic institutions, followed by community hospitals (23%). Medical students (32%), followed by attending physicians (22%), and others (16%) comprised the most common cadre of respondents. About 39% of the participants reported experiencing violence themselves, and 18% reported violence against colleague(s). Verbal violence (48%), emotional abuse (24%), and physical misconduct (14%) were the most common types of violence. Nearly 63% of respondents identified patients or their relatives as the most frequent aggressors. Univariate logistic regression analyses demonstrated that female gender (OR = 2.08; 95%CI: 1.16-3.76, P = 0.014) and higher frequency of night shifts (OR = 2.22; 95%CI: 1.08-4.58, P = 0.030) were associated with significantly higher odds of experiencing violence. More than 50% of HCWs felt less motivated and had decreased job satisfaction post-violent conduct.

A large proportion of HCWS in the Caribbean are exposed to violence, yet the phenomenon remains underreported. As a result, HCWs’ job satisfaction has diminished.

Core Tip: The ViSHWaS-Caribbean study followed the guiding principles from the ViSHWaS global study to identify the probable risk factors, characteristics, and outcomes of violence on Caribbean healthcare workers (HCWs). The results were in line with previous studies carried out worldwide and showed that a large proportion of Caribbean HCWs were exposed to violence, leading to job dissatisfaction. The solution to this problem would be to conduct longitudinal analysis/research. Stakeholders should enact regulatory changes to lessen this dispute, and social activities are necessary to strengthen the bonds between HCWs and the communities they serve.

- Citation: Hadmon R, Pierre DM, Banga A, Clerville JW, Mautong H, Akinsanya P, Gupta RD, Soliman S, Hunjah TM, Hunjah BA, Hamza H, Qasba RK, Nawaz FA, Surani S, Kashyap R. Violence study of healthcare workers and systems in the Caribbean: ViSHWaS-Caribbean study. World J Methodol 2024; 14(3): 92932

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v14/i3/92932.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v14.i3.92932

Healthcare workers (HCWs) face an increased risk of violence worldwide, as per the Pan American Health Organization[1]. However, workplace violence (WPV) in healthcare remains largely tolerated, underreported, and ignored[2]. Although the definition of WPV varies between organizations, nonetheless, it is generally agreed to be both physical and non-physical, inclusive of physical assault, verbal abuse, bullying, intimidation, sexual harassment, and any threatening disruptive behavior at the workplace[3]. According to the World Health Organization, about 62% of HCWs have experi

Numerous studies have been done to quantify the problem, describing the incidence, prevalence, and impact of WPV among HCWs[5,6]. Such studies have led to reforms in regional guidelines and task forces to mitigate the effect of this widespread quagmire[7,8]. However, the paucity of similar studies in developing countries, including those in the Caribbean, creates a vacuum in measures to understand violence against HCWs, its impact on the healthcare sector, and possible mitigation strategies in these regions as well as on a global scale. Thus, the Violence in HCWs and Systems (Vishwas) study was conducted in 110 countries, including countries that make up the Caribbean Islands, to evaluate the global frequency, cause, and outcomes of violence in the healthcare sector field[9].

A 2016 cross-sectional study in Barbados reported that 63% of the nursing and physician respondents experienced at least one episode of violence within one year of the study, with verbal abuse (63%) reported as the most common form, followed by bullying (19%), and sexual harassment (7%)[10]. Patients were reported as the main perpetrators of the violence. Female gender and nurses were more likely to experience violence compared to males and physicians[10]. A single-center study on lateral violence among nurses in a Jamaican hospital reported exposure to lateral violence in 96% of respondents, with 7% rating the exposure as moderate to severe. Respondents stated that lateral violence created a hostile workplace environment, with half of the nurses surveyed sharing an intent to resign[11]. In 2022, two physicians were abducted in Haiti, allegedly due to gang violence, leading to the closure of four hospitals in Haiti in a protest against the increasing vulnerability of HCWs in the country[12]. Though the numbers reported by the few studies conducted in the Caribbean seem egregious, it is essential to note that violence against HCWs remains underreported. Moreover, the few studies conducted in Caribbean countries either focused on one subset of HCWs (e.g., nurses) or were limited to one institution.

This ViSHWaS-Caribbean is a cross-sectional study that aims to understand the risk factors, characteristics, and impact of violence experienced by HCWs in the Caribbean and identify the causal agents and mitigation strategies.

A detailed, step-by-step description of our research methodology is provided in our previous works[9,13]. An overview of the ViSHWaS-Caribbean cross-sectional study methodology is provided in the following sections.

A cross-sectional survey-based observational study was designed to investigate the burden of HCW-related violence in the Caribbean. The study was part of the ViSHWaS global study[9]. The online survey was generated using Research Electronic Data Capture forms.

The ViSHWaS-Caribbean study utilized the core competencies of the Global Remote Research Scholar Program in human subject-based research, global team dynamics, and data collection, analysis, and interpretation and expanded upon the field. The investigators comprised of a core team and country/regional collaborators. The core team met bimonthly to track the progress and discuss strategies to improve participant recruitment.

To maximize the number of responses, a "hub and spoke model" of team building was implemented[14]. A snowball sampling technique was utilized to disseminate the survey through in-person meetings, text messages, emails, and various social media platforms, including LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and X, between June 6th and August 9th, 2022[13].

Various promotional YouTube videos were recorded to achieve a larger viewership, and Spanish and Arabic voice translations of the survey were recorded to cater to a larger audience. Following an eight-week period, 225 unique responses from seven Caribbean countries were collected and later analyzed.

The study adopted a convenience sampling methodology for selecting potential participants from Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago (Figure 1).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Categorical variables, such as the burden of violence and its impact on HCWs, were estimated using percentages. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata software (version 17.0SE, StataCorp). We used simple and multiple logistic regressions for our univariate and multivariate analysis, respectively, to determine potential WPV predictors. The impact of major (independent) and secondary factors on the likelihood of HCW violence was investigated using univariate models. Multivariate-adjusted models were created concurrently to account for the confounding variables. The models' collinearity was introduced by the years of experience and age of the HCWs. Removing the years of experience from the modified models was the solution. Lastly, we used a χ2 test to evaluate the relationships between the gender of HCWs and the four distinct violence subtypes. Regardless of statistical significance, all relevant variables were considered for the multivariate model. A P-value < 0.05 was significant.

The ViSHWaS study was granted an exemption from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Various subsets of the ViSHWaS manuscript[9] have been accepted and published as abstracts for presentation at several regional and international conferences, and in preprints.

Out of a total of 225 HCWs, 61% were females, 51% were in the age category of 26-36, and about 44.4% were mixed race (Table 1). Among the seven Caribbean countries (n = 225), most participants came from Dominica (27.1%), followed by Haiti (22.2%), Grenada (13.8%) Dominican Republic (13.8%), Cuba (11.6%), Trinidad and Tobago (6.2%), and lastly Jamaica (5.3%) (Figure 1). Physicians in training formed 46.7% of the respondents, 21.8% were attending physicians, and 15.6% belonged to “others.” Approximately 68% of participants had > 2 years of healthcare work experience. More than half of the respondents worked in government institutions (academic: 48.9%; non-academic: 7.6%), while 22.7% worked in community hospitals, and 11.5% of participants worked in private settings (Table 1).

| Demographics | n = 225 | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 81 | 36.0 |

| Female | 137 | 60.9 |

| Transgender | 0 | 0.0 |

| Gender variant/non-confirming | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other/prefer not to disclose | 7 | 3.1 |

| Skipped | 0 | 0.0 |

| Age (yr) | ||

| 18-25 | 42 | 18.7 |

| 26-35 | 115 | 51.1 |

| 36-45 | 53 | 23.6 |

| 46-55 | 11 | 4.9 |

| 56-65 | 4 | 1.8 |

| 65+ | 0 | 0.0 |

| Skipped | 0 | 0.0 |

| United States-African American | 13 | 5.8 |

| United States-Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.4 |

| Black-African | 65 | 28.9 |

| South Asian | 1 | 0.4 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 81 | 36.0 |

| Mixed race | 17 | 7.6 |

| Other | 42 | 18.7 |

| Skipped | 5 | 2.2 |

| Type of institution | ||

| Government academic | 110 | 48.9 |

| Government-non-academic | 17 | 7.6 |

| Private academic | 21 | 9.3 |

| Private non-academic | 5 | 2.2 |

| Community hospital | 51 | 22.7 |

| Military hospital | 1 | 0.4 |

| Mission/non-profit hospital | 8 | 3.6 |

| Other | 9 | 4.0 |

| Skipped | 3 | 1.3 |

| Years of experience | ||

| < 1 | 16 | 7.1 |

| 1 to 2 | 54 | 24.0 |

| 2 to 5 | 64 | 28.4 |

| 6 to 10 | 44 | 19.6 |

| 11 to 20 | 36 | 16.0 |

| 21 to 30 | 7 | 3.1 |

| < 30 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Skipped | 3 | 1.3 |

| Work position | ||

| Administration | 9 | 4.0 |

| Nurse practitioner | 2 | 0.9 |

| Attending physician | 49 | 21.8 |

| Auxiliary/support staff | 4 | 1.8 |

| Dentist/dental surgeon | 2 | 0.9 |

| EMT | 0 | 0.0 |

| Fellow in training | 10 | 4.4 |

| Medical student | 71 | 31.6 |

| Occupational therapist | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pharmacist (PharmD) | 1 | 0.4 |

| Physical therapist | 3 | 1.3 |

| Physician assistant | 2 | 0.9 |

| Registered nurse | 11 | 4.9 |

| Researcher | 2 | 0.9 |

| Resident/junior resident in training | 24 | 10.7 |

| Respiratory therapist | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 35 | 15.6 |

| Skipped | 0 | 0.0 |

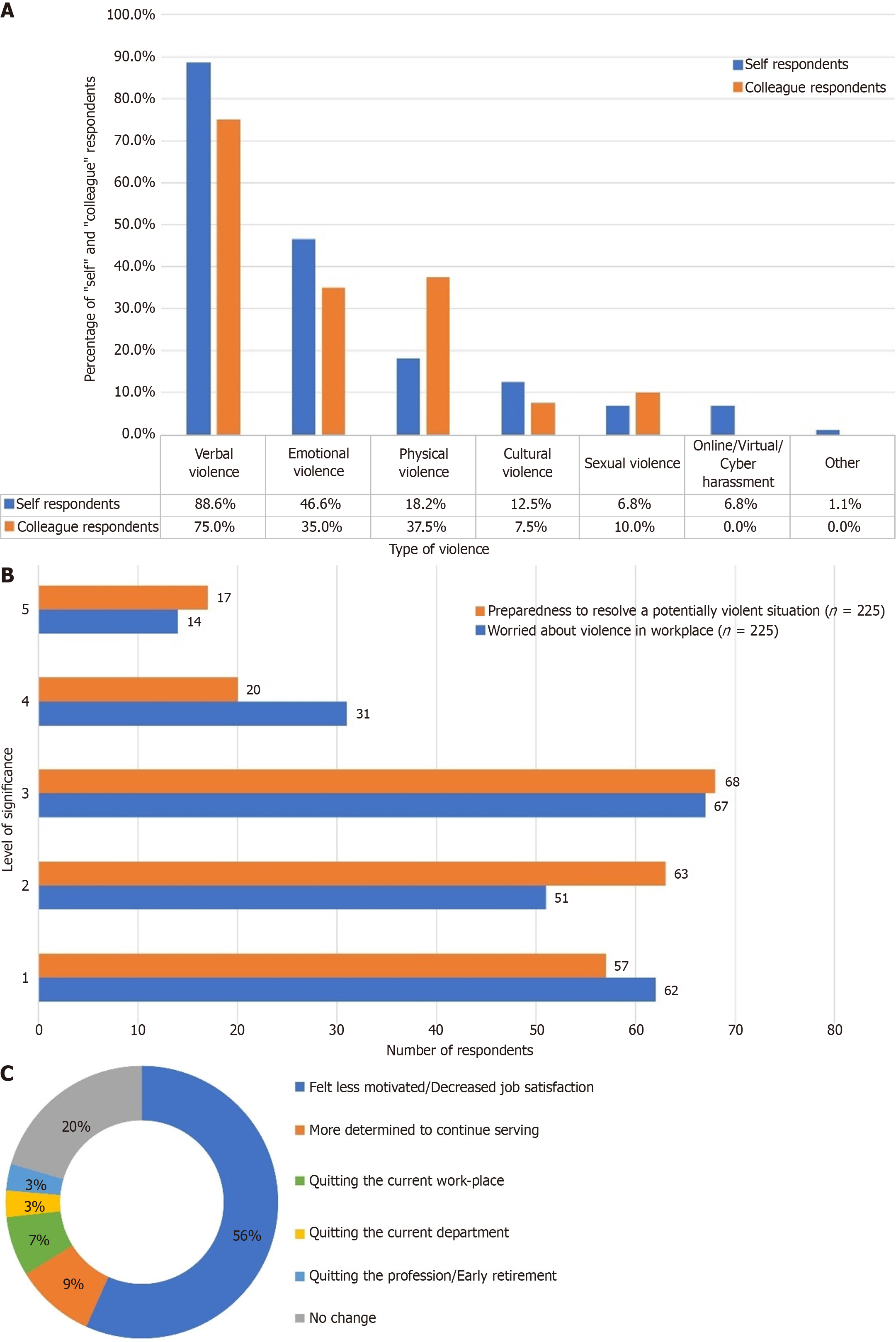

About 39% of the respondents reported experiencing violence themselves, while 17.8% reported violence experienced by their colleague(s). Table 2 highlights that verbal violence (48% of the 225 respondents) was the most common form of violence. Emotional violence was more common amongst “self” respondents (46.6% of 88 vs 35.0% of 40), whereas “colleague” respondents reported more physical violence (18.2% of 88 vs 37.5% of 40) (Figure 2A).

| Violence of any form at workplace | Count (n = 225) | Percentage (%) |

| Total yes response - self + colleague (n = 225) | 128 | 56.9 |

| Yes response-self (n = 225) | 88 | 39.1 |

| Yes response - colleague (n =137) | 40 | 17.8 |

| No response - self + colleague (n = 225) | 97 | 43.1 |

| Form of violence | Count (n = 225) | Percentage (%) |

| Verbal violence | 108 | 48.0 |

| Emotional violence | 55 | 24.4 |

| Physical violence | 31 | 13.8 |

| Cultural violence | 14 | 6.2 |

| Sexual violence | 10 | 4.4 |

| Online/virtual/cyber harassment | 6 | 2.7 |

| Other | 1 | 0.4 |

| Type of aggressor | Count (n =128) | Percentage (%) |

| More than one type of aggressor | 19 | 14.8 |

| Colleague | 9 | 7.0 |

| Patient | 23 | 18.0 |

| Patient and relative and/or caregiver | 8 | 6.3 |

| Patient and relative and/or caregiver | 50 | 39.1 |

| Supervisor | 18 | 14.1 |

| Frequency of violence; during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic | Count (n =128) | Percentage (%) |

| Increased | 37 | 28.9 |

| About the same | 62 | 48.4 |

| Decreased | 28 | 21.9 |

| Number of violent episodes in past one year | Survey respondent-self (n = 88) | Survey respondent-colleague (n = 40) |

| Every day | 1 | 0 |

| About once a week | 8 | 3 |

| A few times a week | 3 | 0 |

| Once or twice a month | 24 | 10 |

| Once or twice a quarter | 18 | 26 |

| Once or twice a year | 34 | 0 |

Among all the HCWs who reported violence against themselves or their colleagues (n = 128), a total of 63.3% of individuals identified patients or their relatives/caregiver/family member as the most frequent aggressors, 14.1% mentioned supervisors, and 14.8% reported encountering more than one type of the aggressor. Nearly half of the respondents (48.4%) felt the frequency of violent incidents to be unaffected by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, while almost one-third (28.9%) felt an increase in incidence among “self” respondents. A violent episode frequency of once-twice a year was predominant (34/88), while the majority of “colleague” respondents (26/40) reported witnessing an episode more frequently, at one-two per quarter (Table 2).

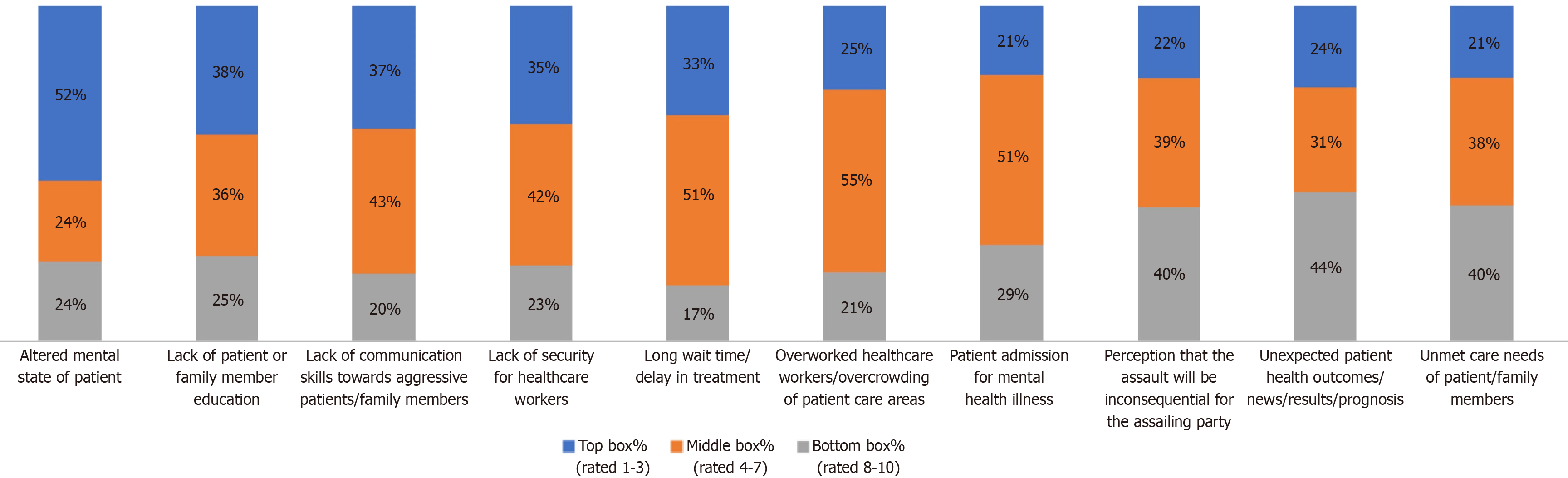

Based on their perception of relevance, survey participants were asked to rank the listed ten likely reasons for violence (Figure 3). Consistent with the global study, 31.2% of HCWs cited the patient's altered mental state as the most important factor. This was followed by a lack of security for HCWs (11.6%) and a delay in treatment (10.4%). Conversely, the unfulfilled requirements of the patient or their family were regarded as the least important reason by 17.6% of HCWs. A further 12.9% of respondents cited the patient's altered mental state as the least significant factor, while 9.6% pointed to the unexpected prognosis as the least significant factor.

Of the 225 survey respondents, 50.2% confirmed the availability of violence reporting protocols at their institutions, while 35.1% had awareness regarding the Occupational Safety and Health guidelines. Nearly 48.4% of the 128 HCWs who reported experiencing violence had reported the incident to their hospital administration or the police (Table 3).

| Results | Count | Percentage (%) |

| Violence incidents reported to the administration or hospital or police (n = 128) | 62 | 48.40 |

| Availability of violence reporting procedures at hospital (n = 225) | 113 | 50.20 |

| Awareness of occupational safety and health standards (n = 225) | 79 | 35.10 |

| Training in violence management (n = 225) | 42 | 18.70 |

| Effect of violence on perception of career | Count (n = 128) | Percentage (%) |

| Felt less motivated/decreased job satisfaction | 72 | 56 |

| More determined to continue serving | 12 | 9 |

| Quitting the current work-place | 9 | 7 |

| Quitting the current department | 4 | 3 |

| Quitting the profession/early retirement | 4 | 3 |

| No change | 26 | 20 |

Out of the 225 survey respondents, 18.7% reported having received training in managing potentially violent conduct, 20% of the respondents felt strongly worried about tackling a violent situation, and 16.4% felt adequately prepared to resolve a potentially violent situation (Figure 2B). Comparably, of the 128 HCWs who reported experiencing violence, 56% lost motivation to work. In contrast, 20% did not let the incident affect them, and another 13% decided to quit their current department, workplace, or profession (Figure 2C) (Table 3).

As shown in Table 4, the univariate logistic regression analyses demonstrated that being female (OR = 2.08; 95%CI: 1.16-3.76, P = 0.014) and working a high frequency of night shifts (OR = 2.22; 95%CI: 1.08-4.58, P = 0.030) were associated with increased odds of having experience violence at the workplace. Amongst various professions, physicians were found to have higher odds of facing violence, with a p-value very close to 0.05 (OR = 4.84; 95%CI: 0.98-23.76, P = 0.052). Whereas work setting, age, and years of experience were not significantly associated with a higher risk of violence.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||||

| OR | Std Err. | 95%CI for B | P value | OR | Std Err. | 95%CI for B | P value | |||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

| Gender1 | ||||||||||

| Female | 2.08 | 0.63 | 1.16 | 3.76 | 0.014 | 1.84 | 0.63 | 0.95 | 3.59 | 0.071 |

| Work setting2 | ||||||||||

| Public setting | 1.44 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 3.13 | 0.358 | 1.25 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 2.99 | 0.618 |

| Other | 0.60 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 3.36 | 0.559 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.13 | 4.92 | 0.804 |

| Profession3 | ||||||||||

| Medical student | 1.89 | 1.56 | 0.38 | 9.5 | 0.440 | 1.89 | 2.29 | 0.18 | 20.20 | 0.598 |

| Nurse | 4.00 | 3.68 | 0.66 | 24.30 | 0.132 | 5.30 | 6.50 | 0.48 | 58.61 | 0.173 |

| Physician | 4.84 | 3.93 | 0.98 | 23.76 | 0.052 | 7.10 | 8.15 | 0.75 | 67.37 | 0.088 |

| Other HCW | 2.14 | 1.84 | 0.41 | 11.42 | 0.360 | 3.10 | 3.65 | 0.31 | 31.29 | 0.337 |

| Age4 | ||||||||||

| 26-35 | 0.80 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 1.63 | 0.534 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.97 | 0.043 |

| 36-45 | 0.95 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 2.15 | 0.90 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 1.39 | 0.160 |

| 46-55 | 1.11 | 0.76 | 0.29 | 4.22 | 0.88 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.63 | 2.82 | 0.372 |

| Years of experience5 | ||||||||||

| 1 to 2 | 0.93 | 0.57 | 0.28 | 3.10 | 0.901 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 to 5 | 1.61 | 0.96 | 0.50 | 5.16 | 0.427 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6 to 10 | 1.52 | 0.94 | 0.45 | 5.14 | 0.498 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11 to 20 | 2.20 | 1.39 | 0.63 | 7.62 | 0.214 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 21 to 30 | 1.65 | 1.54 | 0.26 | 10.31 | 0.592 | - | - | - | - | - |

| > 30 | 0.93 | 0.57 | 0.28 | 3.10 | 0.901 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Night shift frequency6 | ||||||||||

| High | 2.22 | 0.82 | 1.08 | 4.56 | 0.03 | 1.72 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 3.95 | 0.20 |

The same variables were included in the multivariate model to control confounding. It must be noted that years of experience were dropped from the model due to significant collinearity with age. In the multivariate analysis, the 26-35 age group (OR = 0.37; 95%CI: 0.14-0.97, P = 0.043) was the only variable statistically significantly associated with reduced odds of experiencing violence at the workplace. Interestingly, the female gender (OR = 1.84; 95%CI: 0.95-3.59, P = 0.071) and high frequency of night shifts (OR = 1.72; 95%CI: 0.74-3.95, P = 0.205) lost statistical significance and were not associated with increased odds of violence. Similarly, physicians (OR = 4.84; 95%CI: 0.98-23.76, P = 0.088) were not associated with increased odds of violence compared to the reference (Table 4).

Violence against HCWs is not a new phenomenon but has emerged as a potential obstacle to efficient healthcare services[15]. Albeit multiple studies in various regions worldwide emphasize this ever-growing subject, the Caribbean islands, like several other developing countries, have had a difficult time addressing this issue[1]. The ViSHWaS-Caribbean study of seven Caribbean island countries adopted established guiding principles from the ViSHWaS global study and found that majority of the results were consistent with those of other comparable studies conducted in various regions world

The following are some important findings of our study: (1) There is a high prevalence of violent attacks among HCWs in various work environments, regardless of their profession, years of experience, and age; (2) in univariate analysis, female gender (OR = 2.08) and working high frequency of night shifts (OR = 2.22) were associated with significantly increased risk of experiencing violence. However, both variables lost statistical significance in the multivariate analysis when controlled for confounders; and (3) HCWs aged 26-35 years were less likely to witness WPV (OR = 0.80).

The ViSHWaS-Caribbean study findings were consistent with the ViSHWaS global study[9] in terms of the probable cause and outcomes of violence against HCWs. However, unlike the global study, being female HCWs in the Caribbean was associated with a higher risk of facing misconduct. In congruence with our results, a study by George et al[16] also reported that 64% of women cited violence in terms of verbal abuse and 42% violent threats, and females were more prone to experiencing sexual violence (30%) compared to their male colleagues (4%). They also identified young doctors as being at increased risk of violence[16]. This could be attributed to younger physicians having less experience and expertise in communication and handling problematic situations-Another study by Shahjalal et al[17], identified that HCWs working in public healthcare institutions had a higher risk of experiencing physical violence compared to private setups. However, this study reported male HCWs (specifically physicians) of being at higher risk than females, contradicting our findings[17].

The Hospital Safety and Staffing Consumer Survey Report highlighted a few risk factors for violence in healthcare institutions[18]. Staffing shortages, burnout, and mistreatment have emerged as major concerns in managing workload and easing the tensions among staff and patients in the Caribbean. The Pan American Health Organization highlighted that several Caribbean HCWs have migrated due to a lack of respect, work overload, and poor treatment[1]. This has also led to increasing frustration amongst patients and family members, seen through complaints in the media highlighting the dissatisfaction with the healthcare system or response from HCWs. Over time, this phenomenon has evolved into violence against the remaining HCWs in the Caribbean[1,10-12]. Adding to this is the lack of training, experience, and resources in handling such physical and non-physical altercations in healthcare settings[15,19]. The findings of our study indicate that a significant proportion of participants cited a patient's altered state of mind as the most likely factor contributing to incidents of violence against HCWs. This was followed by factors such as inadequate education of the patient or family member, ineffective communication skills when dealing with aggressive patients or family members, insufficient security measures for the HCWs, and treatment delays. On the other hand, unmet care needs of patients or family members, unfulfilled requirements of the patient or their families, and a perception that the assault will be inconsequential for the assailant were considered the least likely explanations. Violence against HCWs can have a detrimental impact on the HCWs, leading to physical hurt, stress disorders, job dissatisfaction and resignation, and even death. This, in turn, damages the healthcare, compromising the patient’s wellness[3,19-21].

Addressing violence against HCWs in the Caribbean will require a multidisciplinary team approach[7]. The Crisis Prevention Institute has identified “de-escalation tips” for HCWs when approaching a problematic situation. This enables staff to identify threatening language and any signs of agitation to prevent possible harm to the staff and patients[22].

The ViSHWaS-Caribbean study provided a clear view of the violence experienced in Caribbean countries. After performing the global ViSHWaS survey[9], a snapshot was taken of the Caribbean HCWs' exposure to violence in comparison to other nations. The healthcare systems were reviewed and provided the researchers with information to gather conclusions based on the study objectives. Additionally, using the survey increases the reliability and validity of the findings. Lastly, the data's anonymity was maintained using de-identified data and a web-based survey design.

It is important to note the limitations of this study. Given that the current research focuses primarily on HCWs, it is possible that this could result in a certain level of bias in the study. Furthermore, response bias poses a concern due to the locations of the self-selected participants and the number of responses with respect to the aggressors of violence among HCWs, which could pose a higher risk of having skewed results. One possible explanation for the skewed results could be the stigma attached to violence in the Caribbean, especially among family and peers. The language was a barrier for a few nations due to the survey being designed in English. The solution to this was for the core team to implement visual and graphical illustrations from educational modes to aid the completion of the surveys. Also, Spanish and Arabic translations were provided via recorded messages and peer-to-peer communications; however, translations to languages like French and Creole were unavailable. Because of the cross-sectional design, we were unable to characterize the prevalence of HCW-related violence.

Furthermore, the responses to the 10-point rating questions may contain bias. Because the replies were arranged alphabetically, some respondents may have given the highest priority to the answers that were featured first. Lastly, these results represent a small sample size from the Caribbean region, which limits generalizability to the entire region.

The high patient volume in the Caribbean nations, in addition to a staff shortage, resources, and financial incentives, makes it increasingly stressful for healthcare professionals to work and provide effective care[1]. The multifaceted nature of violence against HCWs makes it an additional stressor[9]. Institutions need to conduct longitudinal research to fully understand the complexities and quantify the scope of this persistent issue[13]. To reduce this disagreement, stakeholders should implement policy measures and social activities are required to improve connections between HCWs and the communities they serve[7].

A large proportion of HCWS in the Caribbean were exposed to violence, according to the ViSHWaS-Caribbean online cross-sectional survey. As a result, employee happiness has diminished. Legislative initiatives and interpersonal interactions must be implemented to decrease this discord to boost relationships between HCWs and their communities. More studies should be carried out to understand better the burden of violence against HCWs in the healthcare sector in the Caribbean.

| 1. | Health Workers Perception and migration in the Caribbean region. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/health-workers-perception-and-migration-caribbean-region. |

| 2. | Phillips JP. Workplace Violence against Health Care Workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1661-1669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chirico F, Leiter M. Tackling stress, burnout, suicide and preventing the "Great resignation" phenomenon among healthcare workers (during and after the COVID-19 pandemic) for maintaining the sustainability of healthcare systems and reaching the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. J Health Soc Sci. 2022;7:9-13. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Shea T, Sheehan C, Donohue R, Cooper B, De Cieri H. Occupational Violence and Aggression Experienced by Nursing and Caring Professionals. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2017;49:236-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hadavi M, Ghomian Z, Mohammadi F, Sahebi A. Workplace violence against health care workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Safety Res. 2023;85:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yusoff HM, Ahmad H, Ismail H, Reffin N, Chan D, Kusnin F, Bahari N, Baharudin H, Aris A, Shen HZ, Rahman MA. Contemporary evidence of workplace violence against the primary healthcare workforce worldwide: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2023;21:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Arnetz JE. The Joint Commission's New and Revised Workplace Violence Prevention Standards for Hospitals: A Major Step Forward Toward Improved Quality and Safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2022;48:241-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Estryn-Behar M, van der Heijden B, Camerino D, Fry C, Le Nezet O, Conway PM, Hasselhorn HM; NEXT Study group. Violence risks in nursing--results from the European 'NEXT' Study. Occup Med (Lond). 2008;58:107-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Banga A, Mautong H, Alamoudi R, Faisal UH, Bhatt G, Amal T, Mendiratta A, Bollu B, Kutikuppala LVS, Lee J, Simadibrata DM, Huespe I, Khalid A, Rais MA, Adhikari R, Lakhani A, Garg P, Pattnaik H, Gandhi R, Pandit R, Ahmad F, Camacho-Leon G, Ciza N P, Barrios N, Meza K, Okonkwo S, Dhabuliwo A, Hamza H, Nemat A, Essar MY, Kampa A, Qasba RK, Sharma P, Dutt T, Vekaria P, Bansal V, Nawaz FA, Surani S, Kashyap R; For GRRSP-ViSHWaS Study Group. ViSHWaS: Violence Study of Healthcare Workers and Systems-a global survey. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abed M, Morris E, Sobers-Grannum N. Workplace violence against medical staff in healthcare facilities in Barbados. Occup Med (Lond). 2016;66:580-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Morrison Small M, Lindo J, Aiken J, Chin C. Lateral violence among nurses at a Jamaican hospital: a mixed methods study. IJANS. 2017;6:85. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Taylor L. Doctors targeted and hospitals close amid gang violence in Haiti. BMJ. 2022;377:o1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Amal T, Banga A, Bhatt G, Faisal UH, Khalid A, Rais MA, Najam N, Surani S, Nawaz FA, Kashyap R; Global Remote Research Scholars Program. Guiding principles for the conduct of the Violence Study of Healthcare Workers and System (ViSHWaS): Insights from a global survey. J Glob Health. 2024;14:04008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Turek JR, Bansal V, Tekin A, Singh S, Deo N, Sharma M, Bogojevic M, Qamar S, Singh R, Kumar V, Kashyap R. Lessons From a Rapid Project Management Exercise in the Time of Pandemic: Methodology for a Global COVID-19 VIRUS Registry Database. JMIR Res Protoc. 2022;11:e27921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Campbell JC, Messing JT, Kub J, Agnew J, Fitzgerald S, Fowler B, Sheridan D, Lindauer C, Deaton J, Bolyard R. Workplace violence: prevalence and risk factors in the safe at work study. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53:82-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | George AS, Mcconville FE, de Vries S, Nigenda G, Sarfraz S, Mcisaac M. Violence against female health workers is tip of iceberg of gender power imbalances. BMJ. 2020;. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shahjalal M, Alam MM, Khan MNA, Sultana A, Zaman S, Hossain A, Hawlader MDH. Prevalence and determinants of physical violence against doctors in Bangladeshi tertiary care hospitals. Hum Resour Health. 2023;21:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hospital safety, staffing, patient and Visitor Experience Consumer Survey Report GHX. Available from: https://www.ghx.com/resources/white-papers/hospital-safety-survey-report/. |

| 19. | World Health Organization. Preventing violence against health workers. Available from: https://www.who.int/activities/preventing-violence-against-health-workers. |

| 20. | Wu JC, Tung TH, Chen PY, Chen YL, Lin YW, Chen FL. Determinants of workplace violence against clinical physicians in hospitals. J Occup Health. 2015;57:540-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zafar W, Khan UR, Siddiqui SA, Jamali S, Razzak JA. Workplace Violence and Self-reported Psychological Health: Coping with Post-traumatic Stress, Mental Distress, and Burnout among Physicians Working in the Emergency Departments Compared to Other Specialties in Pakistan. J Emerg Med. 2016;50:167-77.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Crisis Prevention Institute. Stop workplace violence against health care workers. 2022. Available from: https://www.crisisprevention.com/Blog/health-care/stop-workplace-violence-against-health-care-workers/. |