Published online Sep 20, 2024. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v14.i3.91810

Revised: May 13, 2024

Accepted: May 27, 2024

Published online: September 20, 2024

Processing time: 162 Days and 11.8 Hours

Acute necrotizing pancreatitis is a severe and life-threatening condition. It poses a considerable challenge for clinicians due to its complex nature and the high risk of complications. Several minimally invasive and open necrosectomy procedures have been developed. Despite advancements in treatment modalities, the optimal timing to perform necrosectomy lacks consensus.

To evaluate the impact of necrosectomy timing on patients with pancreatic necrosis in the United States.

A national retrospective cohort study was conducted using the 2016-2019 Nationwide Readmissions Database. Patients with non-elective admissions for pancreatic necrosis were identified. The participants were divided into two groups based on the necrosectomy timing: The early group received intervention within 48 hours, whereas the delayed group underwent the procedure after 48 hours. The various intervention techniques included endoscopic, percutaneous, or surgical necrosectomy. The major outcomes of interest were 30-day readmission rates, healthcare utilization, and inpatient mortality.

A total of 1309 patients with pancreatic necrosis were included. After propensity score matching, 349 cases treated with early necrosectomy were matched to 375 controls who received delayed intervention. The early cohort had a 30-day readmission rate of 8.6% compared to 4.8% in the delayed cohort (P = 0.040). Early necrosectomy had lower rates of mechanical ventilation (2.9% vs 10.9%, P < 0.001), septic shock (8% vs 19.5%, P < 0.001), and in-hospital mortality (1.1% vs 4.3%, P = 0.01). Patients in the early intervention group incurred lower healthcare costs, with median total charges of $52202 compared to $147418 in the delayed group. Participants in the early cohort also had a relatively shorter median length of stay (6 vs 16 days, P < 0.001). The timing of necrosectomy did not significantly influence the risk of 30-day readmission, with a hazard ratio of 0.56 (95% confidence interval: 0.31-1.02, P = 0.06).

Our findings show that early necrosectomy is associated with better clinical outcomes and lower healthcare costs. Delayed intervention does not significantly alter the risk of 30-day readmission.

Core Tip: Clinical evidence regarding the impact of necrosectomy timing on patient outcomes and healthcare costs remains limited. Utilizing propensity-matched cohorts, this nationwide study evaluates the clinical and economic implications of early versus delayed necrosectomy in patients with pancreatic necrosis. Our findings show that early intervention within 48 hours is associated with lower rates of mechanical ventilation, septic shock, and in-hospital mortality. Early necrosectomy also results in substantial cost savings and shorter hospital stays. Intriguingly, the timing of the procedure does not significantly influence the 30-day readmission hazard ratio. These results contribute to the ongoing debate on the optimal timing of necrosectomy, offering evidence-based insights that could improve patient outcomes.

- Citation: Ali H, Inayat F, Jahagirdar V, Jaber F, Afzal A, Patel P, Tahir H, Anwar MS, Rehman AU, Sarfraz M, Chaudhry A, Nawaz G, Dahiya DS, Sohail AH, Aziz M. Early versus delayed necrosectomy in pancreatic necrosis: A population-based cohort study on readmission, healthcare utilization, and in-hospital mortality. World J Methodol 2024; 14(3): 91810

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v14/i3/91810.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v14.i3.91810

Acute pancreatitis is a complex and potentially lethal disease. It is a leading cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalization burden in the United States[1]. Necrosis of the pancreas or peripancreatic tissue can occur in about 20% of patients with acute pancreatitis[2]. Mortality rates can be as high as 20%-30% for patients with infected pancreatic necrotic collections[3,4]. Patients with necrotizing pancreatitis have historically benefited from surgically removing the necrotic tissue, even in the early phase of the illness[5,6]. It has been suggested that delaying surgery leads to the immune system encapsulating the necrotic pancreatic tissue, making necrosectomy technically easier and possibly decreasing mortality[7,8]. This hypothesis was validated by a randomized controlled trial from 1997 that showed a delay in surgical intervention beyond the first 12 days lowered mortality, as opposed to intervention within the first 72 hours of admission[9]. The mortality rate for those who underwent the procedure after 12 days dropped from 56% to 27%[9]. Since then, there has been a paradigm shift from surgical procedures to less-invasive endoscopic or percutaneous treatment approaches[10]. The debate over when to intervene has resurfaced as mortality and morbidity have declined due to the recent multi

Despite the recognized clinical importance of pancreatic necrosis, there is a lack of large-scale, data-driven epidemiological studies evaluating the effects of the timing of interventions on clinical outcomes and healthcare expenditures. In this study, we aim to compare the impact of early (within 48 hours) versus delayed (after 48 hours) necrosectomy on 30-day readmission rates, healthcare utilization, and in-hospital mortality in patients with pancreatic necrosis using a large national database from the United States.

We carried out a retrospective cohort study using the 2016-2019 Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project[21]. The NRD comprises inpatient admissions and readmissions, accounting for around 60% of all-payer hospitalizations across the United States[21]. Diagnoses and procedures were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes. The study included patients aged 18 years or older with a non-elective admission for pancreatic necrosis (ICD-10 code K85.x). It was further classified based on patients with necrosectomy within 48 hours (cases) or after 48 hours (controls). The timing of necrosectomy was from admission, and all patients included in the study had a primary diagnosis code for necrotizing pancreatitis. Necrose

Baseline patient information included demographic variables (age and gender), index admission length of hospital stay and charges, median household income category, primary insurance, discharge outcome, and 30-day readmission status. As in prior studies, the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was computed to account for multiple comorbidities[23,24].

The outcomes of interest were early readmission rates (within 30 days of index admission), length of stay, hospital costs, and clinical outcomes, including mechanical ventilation, septic shock, portal venous thrombosis, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, acute kidney injury, new renal replacement therapy during admission, and all-cause inpatient mortality.

Little's test was applied to establish if data were missing completely at random (MCAR) with a significance threshold of P < 0.05. The variables with over 2% missing data that failed Little's MCAR evaluation underwent multiple imputations (25 datasets) for sensitivity analysis. Data were analyzed employing descriptive statistics for nonparametric databases. Categorical values were reported as percentages, and continuous variables as medians and interquartile ranges. Pearson's chi-square test was utilized to compare categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. The impact of the timing of each procedure on outcome variables was evaluated using multivariable regression analysis. The risk of readmission and mortality was ascertained by applying Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to demonstrate differences in 30-day readmission among procedure timings. All statistical analyses were executed using the Statistical Software for Data Science (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, United States), version 16.1.

The data were acquired from the NRD, a de-identified, publicly accessible registry. This database protects the privacy of patients, physicians, and hospitals. Therefore, the informed consent was waived as the patient identifiers were removed from the hospitalization data. Institutional review board approval was also not required for this study. According to the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Data Use Agreement, any individual table cell counts of ≤ 10 have been masked to ensure privacy and compliance. In such instances, data are designated as < 10.

In the unmatched cohort, 1309 participants met the selection criteria for the study period. Of these, 69 (5.27%) patients were readmitted within 30 days (Table 1). After propensity score matching, 349 cases (patients who underwent necrose

| Factor | Unmatched patients | Matched patients | ||||

| Within 48 hours (cases) | After 48 hours (controls) | P value | Within 48 hours (cases) | After 48 hours (controls) | P value | |

| Total patients | 420 | 889 | 349 | 375 | ||

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 6.0 (3.0, 10.0) | 23.0 (12.0, 42.0) | < 0.001 | 6.0 (4.0, 11.0) | 16.0 (9.0, 31.0) | < 0.001 |

| Total hospital charges in USD, median (IQR) | 51773.0 (28907.0, 92300.0) | 196571.0 (89244.0, 408072.0) | < 0.001 | 52202.0 (29417.0, 101413.0) | 147418.0 (73243.5, 316993.0) | < 0.001 |

| 30-day readmission | 35 (8.3) | 34 (3.8) | < 0.001 | 30 (8.6) | 18 (4.8) | 0.040 |

| Age in years at admission, median (IQR) | 55.0 (41.0, 66.0) | 52.0 (39.0, 64.0) | 0.080 | 55.0 (42.0, 66.0) | 55.0 (39.0, 64.0) | 0.13 |

| Age groups (years) | 0.068 | 0.061 | ||||

| 18-34 | 51 (12.1) | 144 (16.2) | 38 (10.9) | 57 (15.2) | ||

| 35-49 | 113 (26.9) | 241 (27.1) | 91 (26.1) | 100 (26.7) | ||

| 50-64 | 134 (31.9) | 301 (33.9) | 117 (33.5) | 138 (36.8) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 122 (29.0) | 203 (22.8) | 103 (29.5) | 80 (21.3) | ||

| Elixhauser comorbidity index score | < 0.001 | 0.32 | ||||

| 0 | 32 (7.6) | 18 (2.0) | 20 (5.7) | 18 (4.8) | ||

| 1 | 37 (8.8) | 46 (5.2) | 24 (6.9) | 40 (10.7) | ||

| 2 | 71 (16.9) | 91 (10.2) | 65 (18.6) | 65 (17.3) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 280 (66.7) | 734 (82.6) | 240 (68.8) | 252 (67.2) | ||

| Primary payer | 0.65 | 0.37 | ||||

| Medicare | 129 (33.9) | 260 (30.3) | 112 (35.8) | 109 (30.4) | ||

| Medicaid | 73 (19.2) | 166 (19.4) | 57 (18.2) | 70 (19.6) | ||

| Private | 158 (41.5) | 381 (44.5) | 127 (40.6) | 151 (42.2) | ||

| Other | 21 (5.5) | 50 (5.8) | 17 (5.4) | 28 (7.8) | ||

| Median household income national quartile for patient ZIP Code | 0.28 | 0.53 | ||||

| 1st (0-25th) | 105 (25.5) | 197 (22.3) | 88 (25.7) | 88 (23.6) | ||

| 2nd (26th-50th) | 114 (27.7) | 256 (28.9) | 94 (27.4) | 107 (28.7) | ||

| 3rd (51st-75th) | 109 (26.5) | 271 (30.6) | 87 (25.4) | 109 (29.2) | ||

| 4th (76th-100th) | 84 (20.4) | 161 (18.2) | 74 (21.6) | 69 (18.5) | ||

| Disposition of patient (uniform) | < 0.001 | 0.12 | ||||

| Routine | 264 (62.9) | 396 (44.6) | 211 (60.5) | 214 (57.2) | ||

| Transfer to SNF, STH, ICF, and another facility, or AMA | 57 (13.6) | 182 (20.5) | 47 (13.5) | 60 (16.0) | ||

| HHC | 94 (22.4) | 259 (29.2) | 87 (24.9) | 84 (22.5) | ||

| Factor | Unmatched patients | Matched patients | ||||

| Within 48 hours (cases) | After 48 hours (controls) | P value | Within 48 hours (cases) | After 48 hours (controls) | P value | |

| Total patients | 420 | 889 | 349 | 375 | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 35 (8.3) | 81 (9.1) | 0.64 | 30 (8.6) | 29 (7.7) | 0.67 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 55 (13.1) | 287 (32.3) | < 0.001 | 48 (13.8) | 58 (15.5) | 0.51 |

| Uncomplicated hypertension | 230 (54.8) | 458 (51.5) | 0.27 | 194 (55.6) | 200 (53.3) | 0.54 |

| Chronic pulmonary diseases | 81 (19.3) | 135 (15.2) | 0.062 | 72 (20.6) | 59 (15.7) | 0.087 |

| Uncomplicated diabetes | 70 (16.7) | 119 (13.4) | 0.11 | 58 (16.6) | 53 (14.1) | 0.35 |

| Complicated diabetes | 66 (15.7) | 170 (19.1) | 0.13 | 55 (15.8) | 64 (17.1) | 0.64 |

| Hypothyroidism | 19 (4.5) | 83 (9.3) | 0.002 | 17 (4.9) | 27 (7.2) | 0.19 |

| Renal failure | 29 (6.9) | 66 (7.4) | 0.74 | 24 (6.9) | 25 (6.7) | 0.91 |

| Liver disease | 69 (16.4) | 227 (25.5) | < 0.001 | 54 (15.5) | 55 (14.7) | 0.76 |

| Coagulopathy | 31 (7.4) | 136 (15.3) | < 0.001 | 20 (5.7) | 25 (6.7) | 0.60 |

| Obesity | 60 (14.3) | 204 (22.9) | < 0.001 | 43 (12.3) | 43 (11.5) | 0.72 |

| Weight loss | 118 (28.1) | 444 (49.9) | < 0.001 | 108 (30.9) | 124 (33.1) | 0.54 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorder | 227 (54.0) | 634 (71.3) | <0.001 | 215 (61.6) | 211 (56.3) | 0.14 |

| Iron-deficiency anemia | 33 (7.9) | 67 (7.5) | 0.84 | 29 (8.3) | 24 (6.4) | 0.32 |

| Alcohol abuse | 110 (26.2) | 271 (30.5) | 0.11 | 97 (27.8) | 108 (28.8) | 0.76 |

| Drug abuse | 21 (5.0) | 78 (8.8) | 0.016 | 15 (4.3) | 26 (6.9) | 0.13 |

| Depression | 72 (17.1) | 163 (18.3) | 0.60 | 59 (16.9) | 73 (19.5) | 0.37 |

| Complicated hypertension | 32 (7.6) | 86 (9.7) | 0.23 | 26 (7.4) | 27 (7.2) | 0.90 |

Cases had a lower rate of mechanical ventilation (2.9% vs 10.9%, P < 0.001), septic shock (8% vs 19.5%, P < 0.001), ICU admission (0.6% vs 99%, P < 0.001), acute kidney injury (15.5% vs 30.4%, P < 0.001), and a lower all-cause inpatient mortality (1.1% vs 4.3%, P = 0.01) compared to controls (Table 3). The Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score of ≥ 3 was 68.8% in the early cohort compared to 67.2% in the delayed cohort. In the matched cohort, patients who underwent pancreatic necrosectomy within 48 hours had a significantly shorter median length of stay (6 vs 16 days, P < 0.001) and lower median total hospital charges ($52202 vs $147418, P < 0.001), compared to those who underwent necrosectomy after 48 hours. There was no increased risk of mortality among matched cohorts, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.46 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.11-1.88, P = 0.28].

| Factor | Unmatched patients | Matched patients | ||||

| Within 48 hours (cases) | After 48 hours (controls) | P value | Within 48 hours (cases) | After 48 hours (controls) | P value | |

| Total patients | 420 | 889 | 349 | 375 | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | 14 (3.3) | 155 (17.4) | < 0.001 | < 10 | 41 (10.9) | < 0.001 |

| Septic shock | 38 (9.0) | 239 (26.9) | < 0.001 | 28 (8.0) | 73 (19.5) | < 0.001 |

| Portal venous thrombosis | 35 (8.3) | 71 (8.0) | 0.83 | 30 (8.6) | 27 (7.2) | 0.49 |

| ICU-level admission | < 10 | 145 (16.3) | < 0.001 | < 10 | 37 (9.9) | < 0.001 |

| Acute kidney injury | 64 (15.2) | 330 (37.1) | < 0.001 | 54 (15.5) | 114 (30.4) | < 0.001 |

| New RRT during admission | 15 (3.6) | 43 (4.8) | 0.30 | 13 (3.7) | < 10 | 0.20 |

| Died during hospitalization | < 10 | 50 (5.6) | < 0.001 | < 10 | 16 (4.3) | 0.010 |

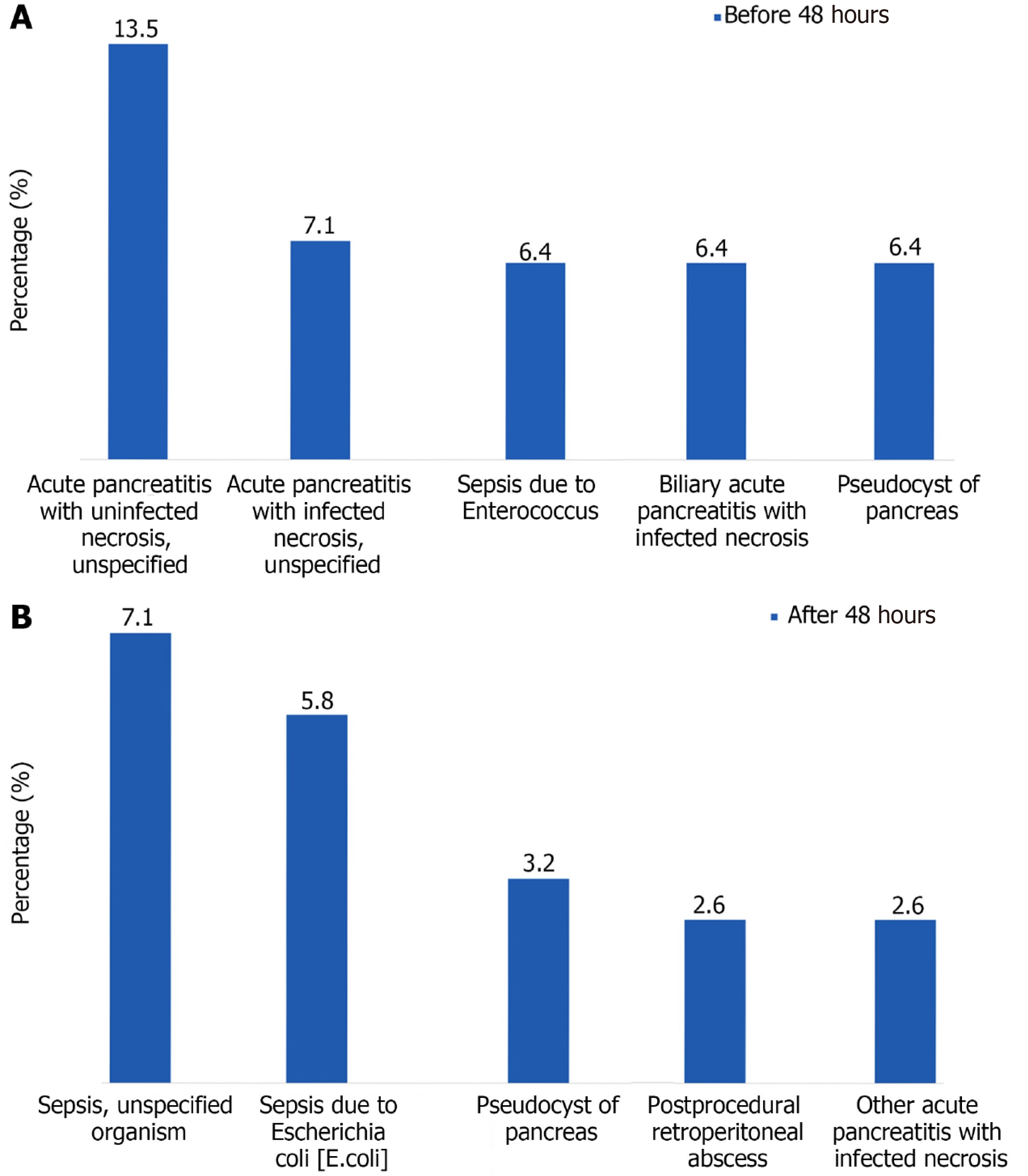

The 30-day readmission rate was higher for patients who underwent necrosectomy within 48 hours (8.6% vs 4.8%, P = 0.040) compared to controls. The top five causes of readmission are delineated (Figure 1). The most common cause of readmission in patients who underwent pancreatic necrosectomy within 48 hours was acute pancreatitis with uninfected necrosis (12.5%). In those who underwent pancreatic necrosectomy after 48 hours, it was sepsis due to infection with an unspecified organism (7.1%).

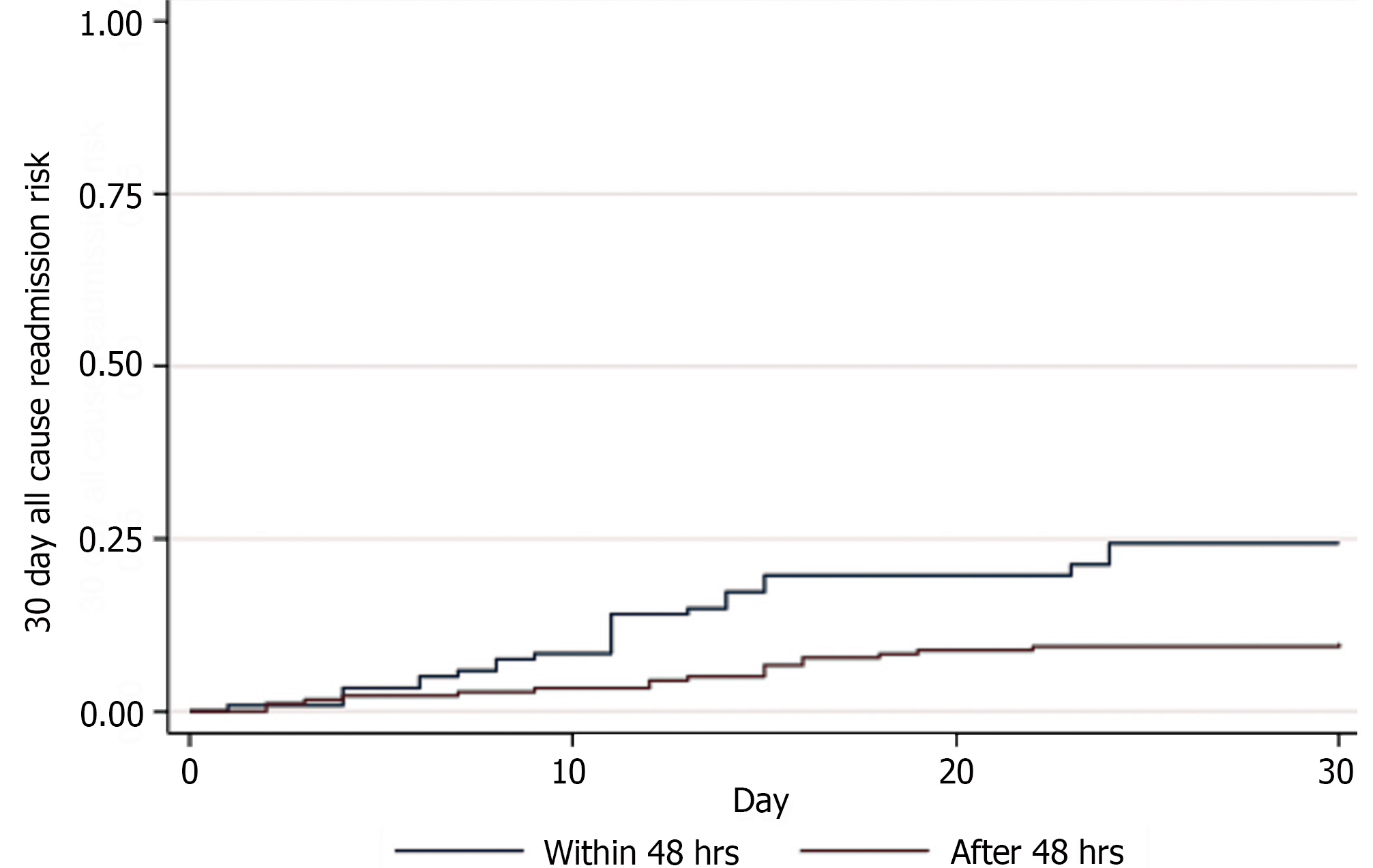

Pancreatic necrosectomy timing did not significantly affect the risk of early readmission [HR 0.56 (95%CI: 0.31-1.02), P = 0.06]. However, pancreatic necrosectomy after 48 hours had a reduced probability of early readmission over necrosectomy within 48 hours with a log rank of 0.07 (Figure 2).

This is the first population-based study to evaluate readmission, healthcare utilization, and in-hospital mortality for early (< 48 hours) versus delayed necrosectomy (> 48 hours) using a national multicenter database. Our findings indicate that early necrosectomy significantly reduces rates of mechanical ventilation, septic shock, and in-hospital mortality. There is a reduced likelihood of readmission after delayed necrosectomy compared to early intervention. However, patients undergoing early intervention have shorter hospital stays and lower inpatient costs.

Hospital readmission constitutes a significant problem in the context of health care policy and reform[25,26]. A number of organizations view readmission rates as a barometer for the quality of healthcare facilities. The body of research on necrotizing pancreatitis-related readmissions has expanded dramatically in recent years. However, there is currently a paucity of clinical evidence comparing the effects of early versus delayed necrosectomy treatments on readmission. In our study, we specifically compared readmission as one of the parameters between early and delayed necrosectomy cohorts. The timing of pancreatic necrosectomy did not significantly affect the risk of early readmission (HR 0.56, P = 0.06). However, necrosectomy after 48 hours showed a reduced probability of 30-day readmission over necrosectomy within 48 hours. One possible reason could be the differences in patient characteristics between the matched cohorts. The early necrosectomy cohort had a relatively higher frequency of patients aged 65 years or older compared to the delayed intervention cohort (29.5% vs 21.3%). A retrospective analysis of 623 patients who underwent pancreatectomy showed that the patient age of ≥ 65 years independently predicted 30-day unplanned readmissions[27]. Similarly, the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score of ≥ 3 has been designated as an important variable for readmission prediction in acute pancreatitis[28,29]. In our analysis, the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score of ≥ 3 was also higher in the early compared to the delayed necrosectomy cohort (68.8% vs 67.2%).

The optimal timing to perform necrosectomy for patients with pancreatic necrosis is still evolving[30]. According to the 2020 clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, the optimal timing for pancreatic debridement should be around four weeks[31]. Early debridement (< 2 weeks after onset) correlates with increased morbidity and mortality[31]. The International Association of Pancreatology/American Pancreatic Association guidelines also suggest that endoscopic treatment for walled-off necrosis be delayed for at least four weeks after the onset of pancreatitis to allow for the encapsulation of necrotic tissue[32]. The delay leads peripancreatic collections to encapsulate, reducing the risk of procedural complications such as bleeding and perforation[33,34]. However, experts recommend early percutaneous drainage for infected or symptomatic necrotic collections[35-39]. Nonetheless, there has been limited investigation into the potential advantages and drawbacks of initiating drainage procedures before the 4-week mark.

The effects of necrosectomy timing on healthcare resource utilization have not been well characterized. Our study revealed that patients in the delayed necrosectomy cohort had greater healthcare utilization and costs. It could be attributed to higher requirements for mechanical ventilation, a greater incidence of septic shock, ICU admission, and acute kidney injury associated with delayed necrosectomy (> 48 hours). Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, commonly seen in severe acute pancreatitis, can lead to multiorgan failure[40,41]. Therefore, delayed intervention may increase the risk of clinical deterioration due to infections and acute inflammatory responses, which can ultimately result in organ failure. It could lead to longer hospitalizations and higher inpatient costs in the delayed intervention group. Contrarily, a recent meta-analysis concluded that patients with early intervention were more likely to have mortality, organ failure, larger fluid collections, and less encapsulation[42]. However, it is possible that the retrospective nature of the studies included in the meta-analysis could have caused a between-group imbalance in patient profiles[42]. Consequently, the increased occurrence of organ failure in the early intervention group might have adversely influenced clinical outcomes[42]. In our cohorts, we could not stratify the individuals according to the specific etiologies of pancreatitis due to inconsistent data availability in the NRD database. Certain etiologies, like post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and autoimmune pancreatitis, may lead to more severe hospital courses. This observation indicates that such etiologies may have an impact on clinical outcomes such as length of stay and mortality. Therefore, future studies should aim to include etiological factors to better understand their influence on the disease course and outcomes.

Our findings show a mortality benefit associated with early compared to delayed necrosectomy (1.1% vs 4.3%, P = 0.01). It could be related to the relatively quick resolution of pancreatic necrosis, which led to a lower rate of complications. An Indian randomized control trial showed that patients with infected necrotizing pancreatitis had a significantly higher and faster resolution of organ failure with proactive percutaneous catheter drainage[43]. A meta-analysis of nine studies based on pooled data from 870 patients showed that there was no significant difference in mortality and complications between early and delayed minimally invasive intervention groups, denoting early intervention as safe for infected pancreatic necrosis[44]. A meta-analysis of four studies analyzing the data of 427 patients who underwent endoscopic treatment also showed no significant difference in rates of mortality and adverse events in early versus late groups[45]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of seven studies also showed no significant mortality or new-onset organ failure difference between early and delayed groups[46]. Therefore, early minimally invasive procedures do not have a negative impact on patient outcomes but may possibly lead to longer hospital and ICU stays[46]. A meta-analysis of six studies based on 630 patients revealed no statistically significant differences in overall adverse events or mortality, but early drainage may prolong the length of stay compared to standard endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage[47]. Our cohort study revealed a mortality benefit, a shorter hospital stay, and a reduced need for ICU admission in the early group compared to the delayed group.

Sepsis was the most common cause of 30-day readmission in patients who underwent delayed necrosectomy. It indicates that more patients in our delayed necrosectomy cohort might have developed infected necrosis. It could also expose these patients to a number of inpatient complications. A retrospective study revealed that postponing necrosectomy until 30 days after index hospitalization had some mortality benefit, but it was associated with longer use of antibiotics and an increased occurrence of infections with Candida species and drug-resistant bacteria[48]. In patients with infected necrosis, Gram-negative infections are frequent, but Gram-positive enterococci and fungi have also been reported[49]. Nonetheless, several randomized controlled trials have revealed that empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics do not influence the likelihood of developing infected necrosis, multiorgan complications, mortality, or surgery in patients with severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis[50-52]. A randomized controlled trial from the United Kingdom advocated for procalcitonin-directed care to lower the administration of antibiotics in patients with acute pancreatitis[53]. Similarly, a retrospective study from China underscored the value of early prognostication of acute pancreatitis based on etiology and disease severity for antibiotic use[54]. Currently, there is insufficient evidence for routine prophylactic use of antifungals in these patients. The existing clinical data also show marked heterogeneity in terms of non-interventional supportive care[55]. Therefore, supportive treatment during the periprocedural period for pancreatic necrosis merits further research[55].

The participants in our study received endoscopic, percutaneous, or surgical necrosectomy procedures. A recent nationwide study of 4605 patients with infected necrosis showed that open debridement had a significantly higher risk of mortality, respiratory failure, mechanical ventilation, and acute kidney injury compared to minimally invasive procedures[56]. In our delayed cohort, patients experienced similar complications and had a higher mortality risk compared to the early cohort. We could not stratify patients based on the respective necrosectomy procedures they received due to NRD data limitations. However, it is plausible that a significant number of patients in our delayed cohort received surgical necrosectomy. A retrospective cohort study from Australia showed that delayed surgical intervention alone may have higher odds of additional complications such as pancreatic fistulae and new-onset diabetes mellitus compared to endoscopic and percutaneous approaches[57]. Furthermore, a retrospective study from the United States showed that endoscopic necrosectomy resulted in reduced morality risk, complications, hospital stay, and inpatient charges compared to percutaneous and surgical procedures[58]. A network meta-analysis of seven studies using pooled data from 400 patients designated the step-up approach with endoscopic debridement as the first choice for infected pancreatic necrosis[59]. Moreover, it was argued that surgical debridement (early and delayed) should be avoided[59]. A meta-analysis of 10 studies based on 570 patients revealed the delayed surgical step-up approach as the optimal choice for acute necrotizing pancreatitis and advocated avoiding drainage alone[60].

Current clinical evidence indicates a regimental shift towards a step-up approach in managing patients with pancreatic necrosis[61-63]. The step-up approach described in a trial from the Netherlands showed better outcomes regarding major complications and mortality than primary open necrosectomy[64]. Similarly, a trial conducted in the United States found no notable discrepancy in mortality rates but a significantly higher rate of complications in the surgical group (pancreatocutaneous fistula) compared to the endoscopic step-up approach[65]. A multicenter trial showed that upfront necrosectomy at the index intervention rather than as a step-up procedure may safely reduce the number of reinterventions in stable patients with fully encapsulated collections and infected necrotizing pancreatitis[66]. However, a cohort study from Germany found that an endoscopic step-up approach reduced peri-interventional morbidity and length of hospital stay[67]. Therefore, further research is warranted to evaluate the best therapeutic strategy utilizing novel technological advancements for patients with pancreatic necrosis[68,69].

This cohort study has several strengths. It has a large sample population, sourced from one of the largest all-payer data sets in the United States. This specific characteristic distinguishes our research from previous studies by providing a reasonable degree of generalizability about the outcomes of early versus delayed necrosectomy. It broadens the applicability of the results in clinical practice compared to single-center experiences with more restricted information on the subject. Using a robust analytical approach, we found that delayed necrosectomy (> 48 hours) is associated with significantly prolonged hospitalization and increased healthcare charges. It offers pertinent real-world insights and clinical evidence to gastroenterologists and gastrointestinal surgeons regarding necrosectomy timing. Therefore, it may aid in informed therapeutic decision-making and prognostic advice. Our results may serve to enable pancreatologists to conduct future studies expanding data on the risks and complications associated with early intervention compared to delayed strategies. It may help to refine patient selection criteria for early necrosectomy, potentially reducing postprocedure adverse clinical outcomes[70]. Further research is warranted to investigate the long-term impact of early versus delayed necrosectomy.

There are certain limitations to our study. The retrospective cohort nature of our design renders it susceptible to the biases commonly associated with such studies. Furthermore, the NRD database lacks specific information on factors such as the severity of acute pancreatitis, the course of hospitalization, treatment modalities, and time intervals related to complications. The database specifies the interval between hospital admission and the necrosectomy procedure. However, it does not include patient data about the interval between hospital admission and the diagnosis of pancreatic necrosis. Our analysis did not account for the specific etiologies of pancreatitis, representing a potential limitation of our findings. We also could not stratify clinical outcomes by specific necrosectomy techniques or individual patients undergoing multiple procedures. Due to the lack of granular data in the database, this study could not specifically track the number or percentage of readmissions due to postprocedure complications. Finally, it is crucial to recognize that human coding errors may occur in the NRD because it is an administrative database reliant on ICD codes for data storage. Despite these constraints, this is the first study to compare patient outcomes between early and late necrosectomy procedures using a nationwide database. It will improve the paucity of data regarding the timing of intervention for pancreatic necrosis.

Our study showed that early necrosectomy was associated with improved clinical outcomes, including decreased risks of septic shock, mechanical ventilation, ICU admission, acute kidney injury, and lower all-cause inpatient mortality. Patients in the early cohort had relatively shorter hospital stays and less expensive medical care. The 30-day readmission rate was higher for patients who underwent early necrosectomy within 48 hours compared to those who received delayed intervention after 48 hours. As the management of necrotizing pancreatitis is continually evolving, our analysis shows that early necrosectomy may have certain clinical benefits over delayed intervention. Therefore, further research is required to stratify the long-term impact of various early interventions on patients with pancreatic necrosis.

| 1. | Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, Jensen ET, Kim HP, Egberg MD, Lund JL, Moon AM, Pate V, Barnes EL, Schlusser CL, Baron TH, Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2021. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:621-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 159.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Boxhoorn L, Voermans RP, Bouwense SA, Bruno MJ, Verdonk RC, Boermeester MA, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2020;396:726-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 582] [Article Influence: 116.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, Besselink MG, Ahmed Ali U, Schrijver AM, Boermeester MA, van Goor H, Dejong CH, van Eijck CH, van Ramshorst B, Schaapherder AF, van der Harst E, Hofker S, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Brink MA, Kruyt PM, Manusama ER, van der Schelling GP, Karsten T, Hesselink EJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Rosman C, Bosscha K, de Wit RJ, Houdijk AP, Cuesta MA, Wahab PJ, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A conservative and minimally invasive approach to necrotizing pancreatitis improves outcome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1254-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 460] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Trikudanathan G, Wolbrink DRJ, van Santvoort HC, Mallery S, Freeman M, Besselink MG. Current Concepts in Severe Acute and Necrotizing Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1994-2007.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chang YC. Is necrosectomy obsolete for infected necrotizing pancreatitis? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16925-16934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Connor S, Neoptolemos JP. Surgery for pancreatic necrosis: "whom, when and what". World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1697-1698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Büchler M, Uhl W, Beger HG. Surgical strategies in acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:563-568. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Husu HL, Kuronen JA, Leppäniemi AK, Mentula PJ. Open necrosectomy in acute pancreatitis-obsolete or still useful? World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mier J, León EL, Castillo A, Robledo F, Blanco R. Early versus late necrosectomy in severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yasuda I, Takahashi K. Endoscopic management of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Brunschot S, Hollemans RA, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Baron TH, Beger HG, Boermeester MA, Bollen TL, Bruno MJ, Carter R, French JJ, Coelho D, Dahl B, Dijkgraaf MG, Doctor N, Fagenholz PJ, Farkas G, Castillo CFD, Fockens P, Freeman ML, Gardner TB, Goor HV, Gooszen HG, Hannink G, Lochan R, McKay CJ, Neoptolemos JP, Oláh A, Parks RW, Peev MP, Raraty M, Rau B, Rösch T, Rovers M, Seifert H, Siriwardena AK, Horvath KD, van Santvoort HC. Minimally invasive and endoscopic versus open necrosectomy for necrotising pancreatitis: a pooled analysis of individual data for 1980 patients. Gut. 2018;67:697-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mohamadnejad M, Anushiravani A, Kasaeian A, Sorouri M, Djalalinia S, Kazemzadeh Houjaghan A, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic or surgical treatment for necrotizing pancreatitis: Comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2022;10:E420-E428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Khan MA, Kahaleh M, Khan Z, Tyberg A, Solanki S, Haq KF, Sofi A, Lee WM, Ismail MK, Tombazzi C, Baron TH. Time for a Changing of Guard: From Minimally Invasive Surgery to Endoscopic Drainage for Management of Pancreatic Walled-off Necrosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shah J, Fernandez Y Viesca M, Jagodzinski R, Arvanitakis M. Infected pancreatic necrosis-Current trends in management. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vanek P, Falt P, Vitek P, Zoundjiekpon V, Horinkova M, Zapletalova J, Lovecek M, Urban O. EUS-guided transluminal drainage using lumen-apposing metal stents with or without coaxial plastic stents for treatment of walled-off necrotizing pancreatitis: a prospective bicentric randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:1070-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Boxhoorn L, van Dijk SM, van Grinsven J, Verdonk RC, Boermeester MA, Bollen TL, Bouwense SAW, Bruno MJ, Cappendijk VC, Dejong CHC, van Duijvendijk P, van Eijck CHJ, Fockens P, Francken MFG, van Goor H, Hadithi M, Hallensleben NDL, Haveman JW, Jacobs MAJM, Jansen JM, Kop MPM, van Lienden KP, Manusama ER, Mieog JSD, Molenaar IQ, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Poen AC, Poley JW, van de Poll M, Quispel R, Römkens TEH, Schwartz MP, Seerden TC, Stommel MWJ, Straathof JWA, Timmerhuis HC, Venneman NG, Voermans RP, van de Vrie W, Witteman BJ, Dijkgraaf MGW, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Immediate versus Postponed Intervention for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1372-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Van Veldhuisen CL, Sissingh NJ, Boxhoorn L, van Dijk SM, van Grinsven J, Verdonk RC, Boermeester MA, Bouwense SAW, Bruno MJ, Cappendijk VC, van Duijvendijk P, van Eijck CHJ, Fockens P, van Goor H, Hadithi M, Haveman JW, Jacobs MAJM, Jansen JM, Kop MPM, Manusama ER, Mieog JSD, Molenaar IQ, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Poen AC, Poley JW, Quispel R, Römkens TEH, Schwartz MP, Seerden TC, Dijkgraaf MGW, Stommel MWJ, Straathof JWA, Venneman NG, Voermans RP, van Hooft JE, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Long-Term Outcome of Immediate Versus Postponed Intervention in Patients With Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis (POINTER): Multicenter Randomized Trial. Ann Surg. 2024;279:671-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Niu CG, Zhang J, Zhu KW, Liu HL, Ashraf MF, Okolo PI 3rd. Comparison of early and late intervention for necrotizing pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dig Dis. 2023;24:321-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jagielski M, Piątkowski J, Jackowski M. Early endoscopic treatment of symptomatic pancreatic necrotic collections. Sci Rep. 2022;12:308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu Z, Liu P, Xu X, Yao Q, Xiong Y. Timing of minimally invasive step-up intervention for symptomatic pancreatic necrotic fluid collections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2023;47:102105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Overview of the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [cited 10 January 2023]. Available from: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nrdoverview.jsp. |

| 22. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5754] [Cited by in RCA: 9926] [Article Influence: 583.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying Increased Risk of Readmission and In-hospital Mortality Using Hospital Administrative Data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55:698-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 627] [Article Influence: 78.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Inayat F, Ali H, Patel P, Dhillon R, Afzal A, Rehman AU, Afzal MS, Zulfiqar L, Nawaz G, Goraya MHN, Subramanium S, Agrawal S, Satapathy SK. Association between alcohol-associated cirrhosis and inpatient complications among COVID-19 patients: A propensity-matched analysis from the United States. World J Virol. 2023;12:221-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmission. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1441-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 553] [Cited by in RCA: 534] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3684] [Cited by in RCA: 3913] [Article Influence: 244.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tosoian JJ, Hicks CW, Cameron JL, Valero V 3rd, Eckhauser FE, Hirose K, Makary MA, Pawlik TM, Ahuja N, Weiss MJ, Wolfgang CL. Tracking early readmission after pancreatectomy to index and nonindex institutions: a more accurate assessment of readmission. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:152-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bogan BD, McGuire SP, Maatman TK. Readmission in acute pancreatitis: Etiology, risk factors, and opportunities for improvement. Surg Open Sci. 2022;10:232-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Munigala S, Subramaniam D, Subramaniam DP, Buchanan P, Xian H, Burroughs T, Trikudanathan G. Predictors for early readmission in acute pancreatitis (AP) in the United States (US) - A nationwide population based study. Pancreatology. 2017;17:534-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nakai Y, Hamada T, Saito T, Shiomi H, Maruta A, Iwashita T, Iwata K, Takenaka M, Masuda A, Matsubara S, Sato T, Mukai T, Yasuda I, Isayama H; WONDERFUL study group in Japan. Time to think prime times for treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis: Pendulum conundrum. Dig Endosc. 2023;35:700-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Baron TH, DiMaio CJ, Wang AY, Morgan KA. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update: Management of Pancreatic Necrosis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:67-75.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 83.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 32. | Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1080] [Cited by in RCA: 1039] [Article Influence: 86.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 33. | van Grinsven J, van Brunschot S, van Baal MC, Besselink MG, Fockens P, van Goor H, van Santvoort HC, Bollen TL; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Natural History of Gas Configurations and Encapsulation in Necrotic Collections During Necrotizing Pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:1557-1564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rashid MU, Hussain I, Jehanzeb S, Ullah W, Ali S, Jain AG, Khetpal N, Ahmad S. Pancreatic necrosis: Complications and changing trend of treatment. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;11:198-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chantarojanasiri T, Yamamoto N, Nakai Y, Saito T, Saito K, Hakuta R, Ishigaki K, Takeda T, Uchino R, Takahara N, Mizuno S, Kogure H, Matsubara S, Tada M, Isayama H, Koike K. Comparison of early and delayed EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collection. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1398-E1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bansal A, Gupta P, Singh AK, Shah J, Samanta J, Mandavdhare HS, Sharma V, Sinha SK, Dutta U, Sandhu MS, Kochhar R. Drainage of pancreatic fluid collections in acute pancreatitis: A comprehensive overview. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:6769-6783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 37. | Mallick B, Dhaka N, Gupta P, Gulati A, Malik S, Sinha SK, Yadav TD, Gupta V, Kochhar R. An audit of percutaneous drainage for acute necrotic collections and walled off necrosis in patients with acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2018;18:727-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, Segovia-Lohse H, Gamberini E, Kirkpatrick AW, Ball CG, Parry N, Sartelli M, Wolbrink D, van Goor H, Baiocchi G, Ansaloni L, Biffl W, Coccolini F, Di Saverio S, Kluger Y, Moore E, Catena F. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 538] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 71.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | van Brunschot S, Fockens P, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Voermans RP, Poley JW, Gooszen HG, Bruno M, van Santvoort HC. Endoscopic transluminal necrosectomy in necrotising pancreatitis: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1425-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Beger HG, Rau B, Isenmann R. Natural history of necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2003;3:93-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4330] [Article Influence: 360.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 42. | Nakai Y, Shiomi H, Hamada T, Ota S, Takenaka M, Iwashita T, Sato T, Saito T, Masuda A, Matsubara S, Iwata K, Mukai T, Isayama H, Yasuda I; WONDERFUL study group in Japan. Early versus delayed interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. DEN Open. 2023;3:e171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Dhar J, Samanta J, Gupta P, Arora SK, Kumar H, Mandavdhare HS, Yadav TD, Gupta V, Sinha S, Kochhar R. Fr290 A comparison between proactive versus standard strategy of percutaneous catheter drainage for management of patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:S284-285. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 44. | Zhu L, Shen J, Fu R, Lu X, Du L, Jiang R, Zhang M, Shi Y, Jiang K. Early versus Delayed Minimally Invasive Intervention for Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Surg. 2022;39:224-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kamal F, Khan MA, Lee-Smith WM, Sharma S, Acharya A, Faggen AE, Farooq U, Tarar ZI, Aziz M, Baron T. Early versus late endoscopic treatment of pancreatic necrotic collections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2023;11:E794-E799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Patoni C, Bunduc S, Levente F, Popescu SI, Veres DS, Harnos A, Péter H, Bálint E, Hegyi PJ. Safety of early vs late endoscopic or percutaneous interventions in infected necrotizing pancreatitis -a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2023;55:S83. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 47. | Ramai D, Enofe I, Deliwala SS, Mozell D, Facciorusso A, Gkolfakis P, Mohan BP, Chandan S, Previtera M, Maida M, Anderloni A, Adler DG, Ofosu A. Early (<4 weeks) versus standard (≥4 weeks) endoscopic drainage of pancreatic walled-off fluid collections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:415-421.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Besselink MG, Verwer TJ, Schoenmaeckers EJ, Buskens E, Ridwan BU, Visser MR, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Gooszen HG. Timing of surgical intervention in necrotizing pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 2007;142:1194-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Schmidt PN, Roug S, Hansen EF, Knudsen JD, Novovic S. Spectrum of microorganisms in infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis - impact on organ failure and mortality. Pancreatology. 2014;14:444-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Isenmann R, Rünzi M, Kron M, Kahl S, Kraus D, Jung N, Maier L, Malfertheiner P, Goebell H, Beger HG; German Antibiotics in Severe Acute Pancreatitis Study Group. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:997-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Dellinger EP, Tellado JM, Soto NE, Ashley SW, Barie PS, Dugernier T, Imrie CW, Johnson CD, Knaebel HP, Laterre PF, Maravi-Poma E, Kissler JJ, Sanchez-Garcia M, Utzolino S. Early antibiotic treatment for severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Surg. 2007;245:674-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | García-Barrasa A, Borobia FG, Pallares R, Jorba R, Poves I, Busquets J, Fabregat J. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ciprofloxacin prophylaxis in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:768-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Siriwardena AK, Jegatheeswaran S, Mason JM; PROCAP investigators. A procalcitonin-based algorithm to guide antibiotic use in patients with acute pancreatitis (PROCAP): a single-centre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:913-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Wen Y, Xu L, Zhang D, Sun W, Che Z, Zhao B, Chen Y, Yang Z, Chen E, Ni T, Mao E. Effect of early antibiotic treatment strategy on prognosis of acute pancreatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Iwashita T, Iwata K, Hamada T, Saito T, Shiomi H, Takenaka M, Maruta A, Uemura S, Masuda A, Matsubara S, Mukai T, Takahashi S, Hayashi N, Isayama H, Yasuda I, Nakai Y. Supportive treatment during the periprocedural period of endoscopic treatment for pancreatic fluid collections: a critical review of current knowledge and future perspectives. J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:98-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Tran Z, Xu J, Verma A, Ebrahimian S, Cho NY, Benharash P, Burruss S. National trends and clinical outcomes of interventional approaches following admission for infected necrotizing pancreatitis in the United States. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;94:665-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Woo S, Walklin R, Wewelwala C, Berry R, Devonshire D, Croagh D. Interventional management of necrotizing pancreatitis: an Australian experience. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:E85-E89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Ramai D, McEntire DM, Tavakolian K, Heaton J, Chandan S, Dhindsa B, Dhaliwal A, Maida M, Anderloni A, Facciorusso A, Adler DG. Safety of endoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy compared with percutaneous and surgical necrosectomy: a nationwide inpatient study. Endosc Int Open. 2023;11:E330-E339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Ricci C, Pagano N, Ingaldi C, Frazzoni L, Migliori M, Alberici L, Minni F, Casadei R. Treatment for Infected Pancreatic Necrosis Should be Delayed, Possibly Avoiding an Open Surgical Approach: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2021;273:251-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Yang Y, Zhang Y, Wen S, Cui Y. The optimal timing and intervention to reduce mortality for necrotizing pancreatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2023;18:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Trikudanathan G, Tawfik P, Amateau SK, Munigala S, Arain M, Attam R, Beilman G, Flanagan S, Freeman ML, Mallery S. Early (<4 Weeks) Versus Standard (≥ 4 Weeks) Endoscopically Centered Step-Up Interventions for Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1550-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Nemoto Y, Attam R, Arain MA, Trikudanathan G, Mallery S, Beilman GJ, Freeman ML. Interventions for walled off necrosis using an algorithm based endoscopic step-up approach: Outcomes in a large cohort of patients. Pancreatology. 2017;17:663-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Maurer LR, Fagenholz PJ. Contemporary Surgical Management of Pancreatic Necrosis. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL, van Ramshorst B, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Timmer R, Laméris JS, Kruyt PM, Manusama ER, van der Harst E, van der Schelling GP, Karsten T, Hesselink EJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Rosman C, Bosscha K, de Wit RJ, Houdijk AP, van Leeuwen MS, Buskens E, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1038] [Cited by in RCA: 1036] [Article Influence: 69.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Bang JY, Arnoletti JP, Holt BA, Sutton B, Hasan MK, Navaneethan U, Feranec N, Wilcox CM, Tharian B, Hawes RH, Varadarajulu S. An Endoscopic Transluminal Approach, Compared With Minimally Invasive Surgery, Reduces Complications and Costs for Patients With Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1027-1040.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Bang JY, Lakhtakia S, Thakkar S, Buxbaum JL, Waxman I, Sutton B, Memon SF, Singh S, Basha J, Singh A, Navaneethan U, Hawes RH, Wilcox CM, Varadarajulu S; United States Pancreatic Disease Study Group. Upfront endoscopic necrosectomy or step-up endoscopic approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis (DESTIN): a single-blinded, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:22-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Timmermann L, Schönauer S, Hillebrandt KH, Felsenstein M, Pratschke J, Malinka T, Jürgensen C. Endoscopic and surgical treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis-a comparison of short- and long-term outcome. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2024;409:58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Saumoy M, Trindade AJ, Bhatt A, Bucobo JC, Chandrasekhara V, Copland AP, Han S, Kahn A, Krishnan K, Kumta NA, Law R, Obando JV, Parsi MA, Trikudanathan G, Yang J, Lichtenstein DR. Endoscopic therapies for walled-off necrosis. iGIE. 2023;2:226-239. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 69. | Binda C, Fabbri S, Perini B, Boschetti M, Coluccio C, Giuffrida P, Gibiino G, Petraroli C, Fabbri C. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Drainage of Pancreatic Fluid Collections: Not All Queries Are Already Solved. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Lu J, Cao F, Zheng Z, Ding Y, Qu Y, Mei W, Guo Y, Feng YL, Li F. How to Identify the Indications for Early Intervention in Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis Patients: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study. Front Surg. 2022;9:842016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |