Published online Jun 20, 2024. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v14.i2.90708

Revised: February 7, 2024

Accepted: April 24, 2024

Published online: June 20, 2024

Processing time: 185 Days and 11.2 Hours

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) is a popular technology among the diabetic population, especially in patients with type 1 diabetes and those with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin. The American Diabetes Association recom

Core Tip: This original brief report proposes and explains how to use a graph from financial markets to synthesize the continuous glucose monitoring (CMG) data. Specifically, Japanese candlestick chart for diabetes would save time for both the doctor and the patient in detecting glycemic trends and maximums and minimums at a glance. This work responds to the need to standardize and simplify CMG reports in order to improve decision making in diabetes control.

- Citation: Boj-Carceller D. Japanese candlestick charts for diabetes. World J Methodol 2024; 14(2): 90708

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v14/i2/90708.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v14.i2.90708

The present work arises from the observed similarity between price action in financial markets and glucose fluctuations in patients with diabetes. In recent years, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has become popular due to the accessibility of flash glucose-sensing technology. Diabetic patients can read their interstitial glucose minute by minute without the use of annoying needles. CGM also alerts users to trends. These systems have been greatly received[1,2].

The 2023 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes[3] recommend standardization of CGM reports with visual indications, such as ambulatory glucose profile (AGP), with a level of evidence ‘E’ based on expert consensus or clinical experience. This can help both the patient and specialist to have a better interpretation of the data to guide treatment decisions.

The AGP is a summary of glucose values for the reporting period, with the median (50%) and other percentiles displayed as if they occurred on a single day. Time in range is associated with a risk of microvascular complications. In 2017, the following glucose targets were established by consensus: 70-180 mg/dL for most people with diabetes and 63-140 mg/dL for pregnant women with diabetes[4]. Time below-range and above-range are useful for evaluation of the therapeutic plan.

Interpretation of an AGP report is not obvious, and some rules in the form of the algorithm are necessary for the doctor and patient to understand and improve glycemic control[5]. Although the AGP report provides a useful overview of the glycemic profile, it is also necessary to review daily glucose profiles to ensure that important glycemic excursions are not missed (e.g., an individual with a severe hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic event that may not be revealed in the AGP report)[6].

The limitations of needing to train the doctor and patient in order to interpret a summary and needing to carefully scrutinize the daily record imply an intellectual and time-consuming effort. This fact may justify the inconsistency of randomized controlled trials made with flash glucose-sensing technology in terms of improving glycemic control and preventing severe hypoglycemia in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with studies showing positive[7,8] and negative results[2,9]. In observational and real-life studies, individuals with type 1 diabetes generally improve glycemic control with these devices but not in all cases[10]. It seems that the doctor and patient have an excess of information that is not always profitable. For this technology to be cost efficient we must be able to extract the maximum relevant information in the shortest time possible[5].

Daily glucose profiles are line graphs that have glucose (mg/dL) on the ordinate axis and time on the abscissa from midnight to midnight. Price in financial markets has traditionally been represented in the West in a similar way: as a line graph that shows a line joining the closing prices for each moment in time[11]. In this way, a similarity between glucose behavior in the daily glucose profile and the price in financial markets can be seen.

Japanese candlestick charts, also known as candlestick charts, are easier to view than line charts, and they provide extra information. The Japanese have been using them for centuries. Nison[12] introduced them to the Western world a few years ago, but it was Homma, a rice merchant, who developed them in the 18th century. He managed to identify that the price of rice was influenced not only by supply and demand but also by traders’ emotions. As their name indicates, Japanese candlestick charts are a graphic representation in the form of candles of price action in financial markets. They represent price movement but include more information within each candle. Additionally, Japanese candlestick patterns show and predict price variations. Traders prefer to read candlestick charts because they provide much more information than a line chart and can be much more useful in making prudent decisions[13].

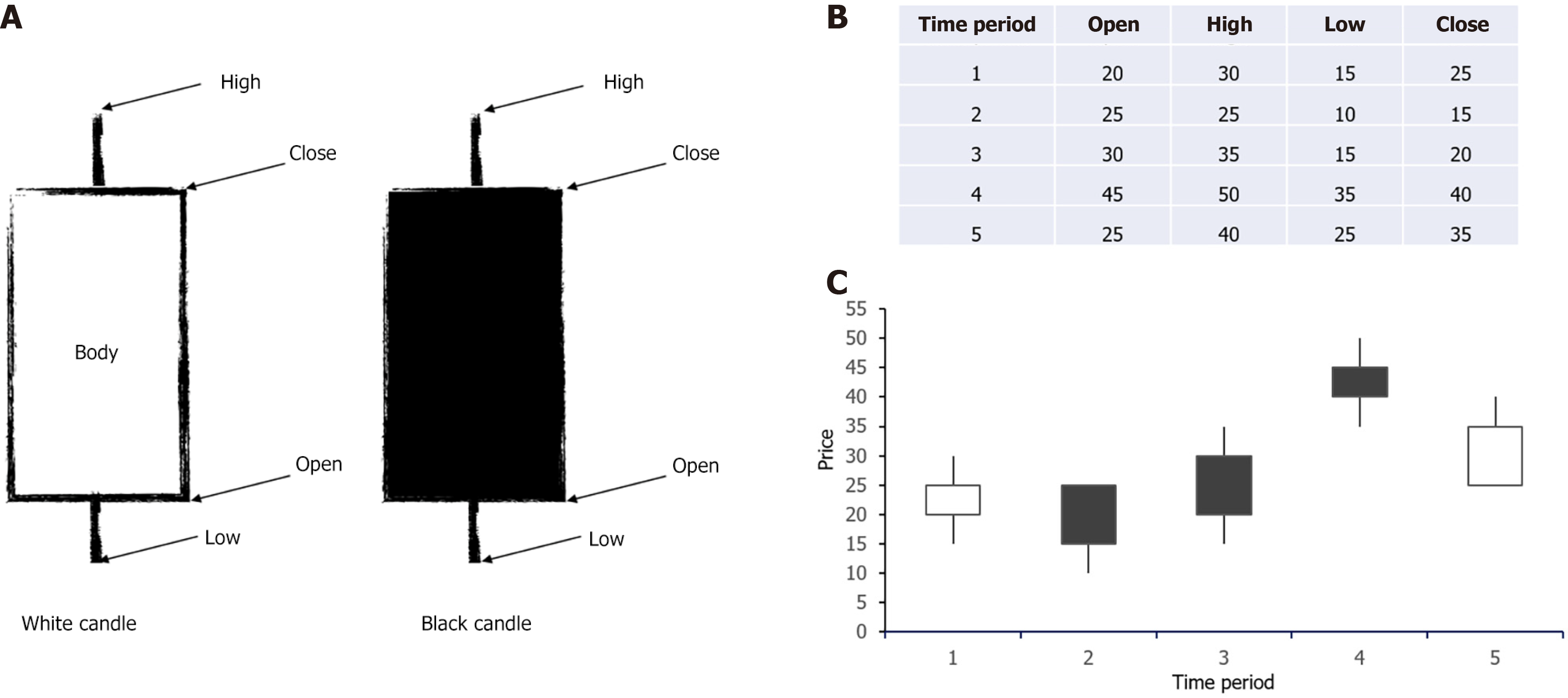

Information used to reflect the situation of a market through a candlestick chart is the opening, maximum, minimum, and closing price (Figure 1). Although other types of graphs called bar graphs use the same information, candlestick graphs are visually much more attractive, facilitating interpretation and analysis of data[14]. Similarly, to represent the daily glucose profile on a candlestick chart (daily summary candle), we would use fasting glucose, maximum glucose, minimum glucose, and bedtime glucose.

In a candlestick chart, the rectangle is called the body and represents the difference between the opening price, which would be equivalent to the glucose check before breakfast, and the closing price of the same day, which would be the last glucose check of the day before bed. The last glucose check is often informative to prevent the dreaded nocturnal hypoglycemia. Opening and closing prices are very important in Japanese candles and in the real life of diabetic patients.

The color of the Japanese candle indicates whether the market is bullish or bearish [i.e. if price (or glucose) has increased or decreased]. A white or green body means that the closing price was greater (higher) than the opening price; the patient goes to bed with a higher glucose level than when fasting. A black or red body means that the closing price was lower than the opening price; the patient goes to bed with a lower glucose level than when fasting.

Lines on the top and bottom of the body are called wicks, hairs, shadows, or highlights. They represent the maximum and minimum prices of the day or the highest and lowest glucose level that the patient has had. They allow detection of the maximum and/or minimum glycemic excursions very easily on a specific day.

After the close of the previous candle, a new one begins to form and the starting point is the closing level of the previous candle. That is the opening price of a Japanese candle. The closing price is the highest level of the body of the Japanese candlestick, if it is bullish. If it is bearish, it will be the lowest point of the body. From that level, the next candle begins. When the opening and closing prices are the same, they are called a doji candle.

As expert technical analysts evaluate the probability of a price reversal or a trend change, they prefer to rely more on patterns formed by two or more successive candles rather than by individual Japanese candles. In the same way, in diabetes we adjust insulin treatment after observing the evolution of glycemic control for 2-3 d, except in cases of risky glycemic excursions, in which we act immediately. To carry out a successful financial operation, waiting for confirmation from the pattern before carrying out any act of purchase or sale is required. This waiting rule applies even in cases where patterns predict market reversals with a high success rate. It is of the utmost importance to be patient until confirmation arrives. As we see, in the management of diabetes we proceed in a similar way.

Japanese candles can be used in any time frame (minute, hour, day, month). The longer the time frame, the less noise has been made. As we have seen, they allow the identification of trends through colors and maximum and minimum values.

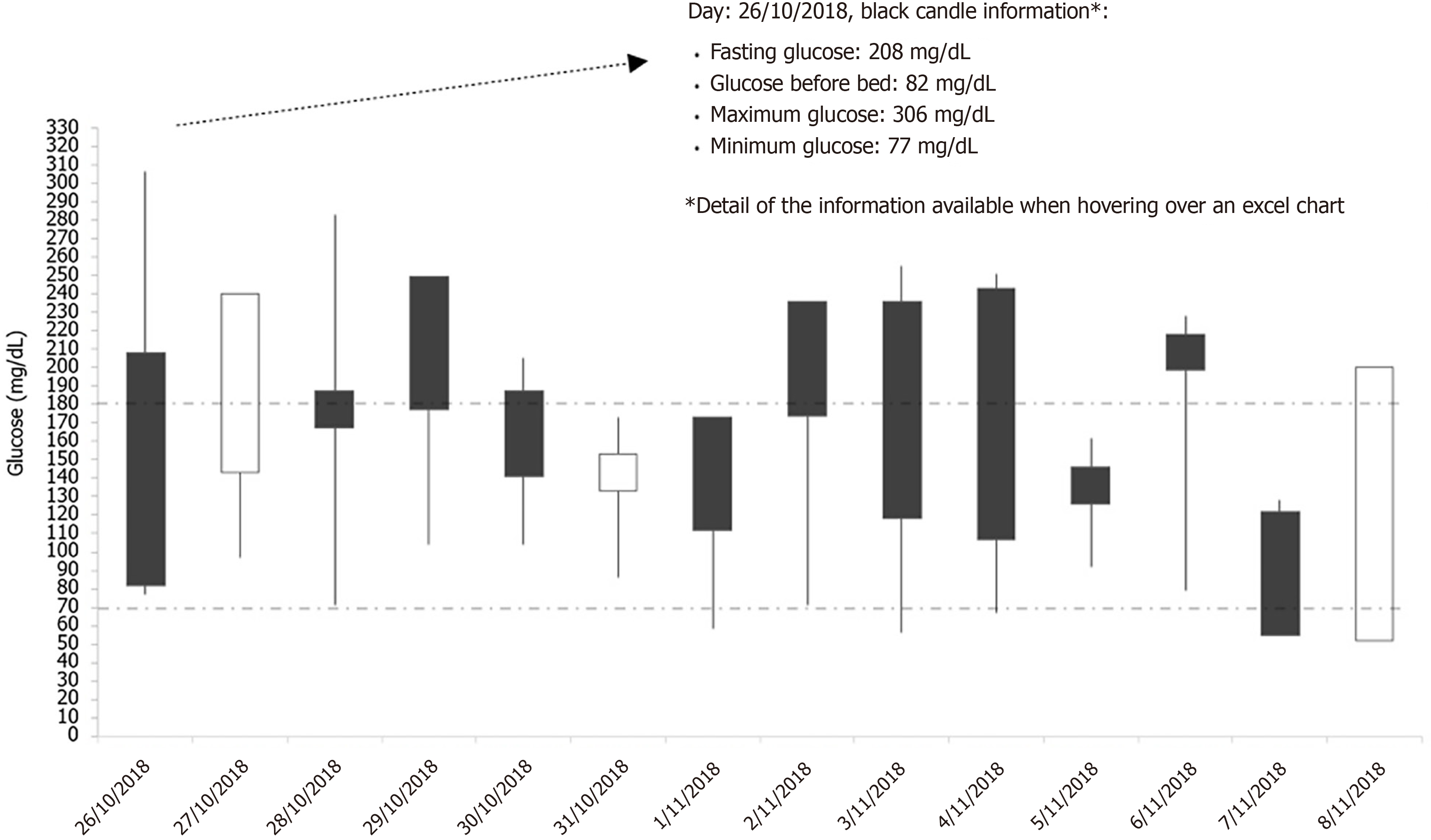

Figure 2 represents a daily glucose profile represented by a candlestick chart for a time frame of 14 d. As can be seen, it is easier to quickly draw conclusions from the candlestick chart regarding glucose pattern and hypo/hyperglycemia (minimums and maximums) if there are any.

In the example, most of candles are black, which indicated that the patient went to bed with lower glucose levels than when she/he woke up. However, fasting figures are mostly above range. Most bodies exceed the recommended range. We also see that this patient suffered five episodes of hypoglycemia, with the lowest level of 52 mg/dL. Therefore, it can be concluded that glycemic control must be optimized and the tendency toward hypoglycemia prevented.

Candlestick charts could also be useful in the hospital where most patients with diabetes do not have CGM but are subject to intensive capillary glucose control. These charts quickly provide information on trends and daily lows and highs.

In conclusion, the use of the Japanese candlestick chart in the graphical representation of glycemic control, especially in the AGP report and in situations of intensive capillary glycemic control, should be considered. The Japanese candlestick chart can compare the current trend with previous periods and identify minimum and maximum glucose values at a glance as well as glucose patterns throughout the day. Collecting the “closing” glucose of the day should be useful to prevent nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade D, Grade D

Novelty: Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade C

P-Reviewer: Ma JH, China S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Yaron M, Roitman E, Aharon-Hananel G, Landau Z, Ganz T, Yanuv I, Rozenberg A, Karp M, Ish-Shalom M, Singer J, Wainstein J, Raz I. Effect of Flash Glucose Monitoring Technology on Glycemic Control and Treatment Satisfaction in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1178-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Boucher SE, Gray AR, Wiltshire EJ, de Bock MI, Galland BC, Tomlinson PA, Rayns JA, MacKenzie KE, Chan H, Rose S, Wheeler BJ. Effect of 6 Months of Flash Glucose Monitoring in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes and High-Risk Glycemic Control: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2388-2395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, Collins BS, Hilliard ME, Isaacs D, Johnson EL, Kahan S, Khunti K, Leon J, Lyons SK, Perry ML, Prahalad P, Pratley RE, Seley JJ, Stanton RC, Gabbay RA; on behalf of the American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S97-S110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 193.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Danne T, Nimri R, Battelino T, Bergenstal RM, Close KL, DeVries JH, Garg S, Heinemann L, Hirsch I, Amiel SA, Beck R, Bosi E, Buckingham B, Cobelli C, Dassau E, Doyle FJ 3rd, Heller S, Hovorka R, Jia W, Jones T, Kordonouri O, Kovatchev B, Kowalski A, Laffel L, Maahs D, Murphy HR, Nørgaard K, Parkin CG, Renard E, Saboo B, Scharf M, Tamborlane WV, Weinzimer SA, Phillip M. International Consensus on Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1631-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1375] [Cited by in RCA: 1377] [Article Influence: 172.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | García-Fernández E. ¿Cómo valorar los datos de las descargas de la monitorización continua de glucosa en la diabetes tipo 1? [cited 29 October 2023]. In: Revista Diabetes. Available from: https://www.revistadiabetes.org/tecnologia/como-valorar-los-datos-de-las-descargas-de-la-monitorizacion-continua-de-glucosa-en-la-diabetes-tipo-1/. |

| 6. | Matthaei S, Dealaiz RA, Bosi E, Evans M, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn N, Joubert M. Consensus recommendations for the use of Ambulatory Glucose Profile in clinical practice. Br J Diab Vasc Dis. 2014;14:153-157. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bolinder J, Antuna R, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn P, Kröger J, Weitgasser R. Novel glucose-sensing technology and hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, non-masked, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2254-2263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in RCA: 650] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Haak T, Hanaire H, Ajjan R, Hermanns N, Riveline JP, Rayman G. Flash Glucose-Sensing Technology as a Replacement for Blood Glucose Monitoring for the Management of Insulin-Treated Type 2 Diabetes: a Multicenter, Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:55-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Davis TME, Dwyer P, England M, Fegan PG, Davis WA. Efficacy of Intermittently Scanned Continuous Glucose Monitoring in the Prevention of Recurrent Severe Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2020;22:367-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nathanson D, Svensson AM, Miftaraj M, Franzén S, Bolinder J, Eeg-Olofsson K. Effect of flash glucose monitoring in adults with type 1 diabetes: a nationwide, longitudinal observational study of 14,372 flash users compared with 7691 glucose sensor naive controls. Diabetologia. 2021;64:1595-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tradingview: El índice S&P 500. [cited 30 October 2023]. Available from: https://es.tradingview.com/symbols/SPX/?exchange=SP. |

| 12. | Nison S. Las velas japonesas: una guía contemporánea de las antiguas técnicas de inversión de Extremo Oriente. Barcelona: Valor Editions, 2014. |

| 13. | Blanco-Garzón E. Trading con velas japonesas. Qué son, patrones más comunes y estrategias. [cited 20 March 2023]. In: Admirals. Available from: https://admiralmarkets.com/es/education/articles/forex-basics/velas-japonesas-todo-lo-que-necesitas-saber-sobre-su-trading. |

| 14. | Murphy JJ. Análisis técnico de los mercados financieros. Barcelona: Gestión 2000, 2016. |

| 15. | Nison S. Japanese candlestick charting techniques. A contemporary guide to the ancient investment techniques of the far east (2nd ed). New York: New York Institute of Finance, 2001. |