Published online May 20, 2021. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v11.i3.81

Peer-review started: January 18, 2021

First decision: February 14, 2021

Revised: February 15, 2021

Accepted: March 18, 2021

Article in press: March 18, 2021

Published online: May 20, 2021

Processing time: 113 Days and 21.3 Hours

Intussusception is defined as invagination of one segment of the bowel into an immediately adjacent segment. The intussusception refers to the proximal segment that invaginates into the distal segment, or the intussusception (recipient segment). Intussusception, more common occur in the small bowel and rarely involve only the large bowel. In direct contrast to pediatric etiologies, adult intussusception is associated with an identifiable cause in almost all the symptomatic cases while the idiopathic causes are extremely rare. As there are many common causes of acute abdomen, intussusception should be considered when more frequent etiologies have been ruled out. In this review, we discuss the symptoms, location, etiology, characteristics, diagnostic methods and treatment strategies of this rare and enigmatic clinical entity in adult.

Core Tip: Intussusception in adult is rare, but its onset is often tumor-related. The diagnosis of intussusception in adult is challenging as a result of the nonspecific signs and symptoms. We herein discuss the epidemiology and the clinical features of bowel intussusception in adult and the role of radiology and surgery in the management of this insidious condition.

- Citation: Panzera F, Di Venere B, Rizzi M, Biscaglia A, Praticò CA, Nasti G, Mardighian A, Nunes TF, Inchingolo R. Bowel intussusception in adult: Prevalence, diagnostic tools and therapy. World J Methodol 2021; 11(3): 81-87

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v11/i3/81.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v11.i3.81

The term intussusception refers to the invagination of a segment of the gastrointestinal tract into the lumen of an adjacent segment[1]. This condition lead to a transient or permanent bowel obstruction that can evolve even to intestinal ischemia. Intus

Adult intussusceptions often onsets as an intermittent cramping abdominal pain associated with signs of bowel obstruction[3]. Diagnosis of intussusception in adult is challenging since the acute abdominal pain is at the same time a non-specific symptom and one of the most frequent complaint reported in the setting of emergency medicine.

Past medical history, physical exam and laboratory test can aid to increase the level of suspicion, but imaging is almost always needed to make diagnosis of bowel intussusception. Although abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan is useful in this setting, it has low specificity in differentiate malignant, benign or idiopathic lead points[4-6].

The optimal management for adult intussusception is still controversial, nevertheless its definitive treatment consists in surgical intervention with appropriate approach depending on the underlying etiology and location.

Any perturbation of the normal pattern of intestinal peristalsis increase the risk of intussusception[7]. As opposed to the pediatric population, adult intussusception is commonly caused by a pathologic lead point; it can be located in the lumen of the bowel, inside the wall or extramural[8], and its occurrence is associated to an identi

| Benign | Malignant |

| Enteric | |

| Adherences, coeliac disease, Crohn’s disease, endometriosis, hamartoma, infections, Kaposi sarcoma, lipoma, Meckel diverticulum, neurofibroma, polyps (inflammatory, adenomatous), stromal tumor, tubercolosis | Adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumors, leiomyosarcoma, lymphoma, malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor, metastatic carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor |

| Colonic | |

| Adherences, inflammatory pseudopolyp, lipoma, polyps (inflammatory, adenomatous) | Adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, sarcoma |

Malignant and benign neoplasms account for 60% of cases with a lead point; the remaining non-idiopathic cases are usually caused by postoperative adherences, Crohn’s disease, infections, intestinal ulcers, and Meckel diverticulum[7,11].

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis from Hong et al[12] 1229 adults with intussusception were identified from 40 retrospective case series: Pooled rates of malignant and benign tumors and idiopathic etiologies were 32.9%, 37.4% and 15.1%, respectively.

According to several reports[7-9,11], when dividing etiologies by enteric and colonic location, the small bowel intussusception is more often caused by benign lesions. In contrast, colonic intussusception is more likely to have an underlying malignant lead point (often a colonic adenocarcinoma). When the small bowel intussusception is induced by malignant lesions these are often metastatic disease (i.e., carcinomatosis).

Notably the ileocolic location in adult intussusception is a variant in which almost the totality of cases has a malignant lead point involving the ileocecal valve[9] (Table 2).

| Ileocolic | |

| Malignant | Adenocarcinoma, metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

As previously mentioned, bowel intussusception afflicts children more than adults with an approximate ratio of 20 to 1. In fact intussusception in adult account for < 5% of all cases of intussusception and is found in 1% of patients with bowel obstruction[7], with a surgical report of less than 1 in 1300 abdominal operations[13]. Usually it involves adults, after the fifth decade, with no difference among male and female[8].

The bowel intussusception is commonly classified in four types according to the land-marks of its origin and extension: (1) Enteric type: the intussusception is limited to the small intestine; (2) Ileocolic type: the ileum passes the ileocolic segment, but the appendix does not invaginate; (3) Ileocecal type: the ileocecal portion invaginates into the ascending colon; and (4) Colocolonic type: the intussusception is limited to the colon and rectum (no anal protrusion).

Small bowel is more often involved by intussusception rather than large bowel. Based on the systematic review of Hong et al[12] the pooled rates of enteric, ileocolic, and colonic location types account for 49.5%, 29.1%, and 19.9%, respectively.

This predominance of enteric intussusception has its exception in the populations of the central and western Africa in which is most common the cecocolic intussusception (tropical intussusception)[14] probably for the interaction of dietary habits (high-fiber diet), genetics and gut microbiome features.

The most common locations involved in intussusception are at the junctions between mobile and fixed segments of the bowel, such as between the freely-moving ileum and the retroperitoneal cecum[8].

Part of a proximal segment of the bowel slides into the next distal section. This event can lead to bowel obstruction and intestinal ischemia. The compromised blood flow to the affected segment can cause necrosis of the intestinal wall with bacterial translo

Pain is the most common symptom reported at a rate of up to 80% in several series[11,12,17,18].

The patient present abdominal tenderness and signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (i.e., hypothermia or hyperthermia, hypotension, and tachycardia). Fever is usually a sign of the onset of intestinal necrosis. Decreased or absent bowel sounds can be present as well as signs of parietal peritoneal irritation, failure to gas passage, abdominal masses, and diarrhoea even with bloody stool. Laboratory tests usually document increase of leukocytes count and inflammatory markers such as polymerase chain reaction.

As already extensively presented in previous studies, the preoperative diagnosis of bowel intussusception raises several questions to the doctor and in this regard, a paper published by Reijnen et al[19] report a preoperative diagnostic rate of 50%.

Intestinal intussusception presents considerable variability in the patient's clinical presentation (abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea) and shows signs of palpable abdominal masses on objective examination.

To make a correct differential diagnosis with other similar intestinal pathologies, it is therefore useful to use radiodiagnostic instruments: abdomen X-ray, small bowel series with barium, abdominal ultrasound, abdominal CT.

Intussusceptions are classified according to location (enteroenteric, ileocolic, ileocecal, or colo-colic) and cause (benign, malignant, or idio-pathic).

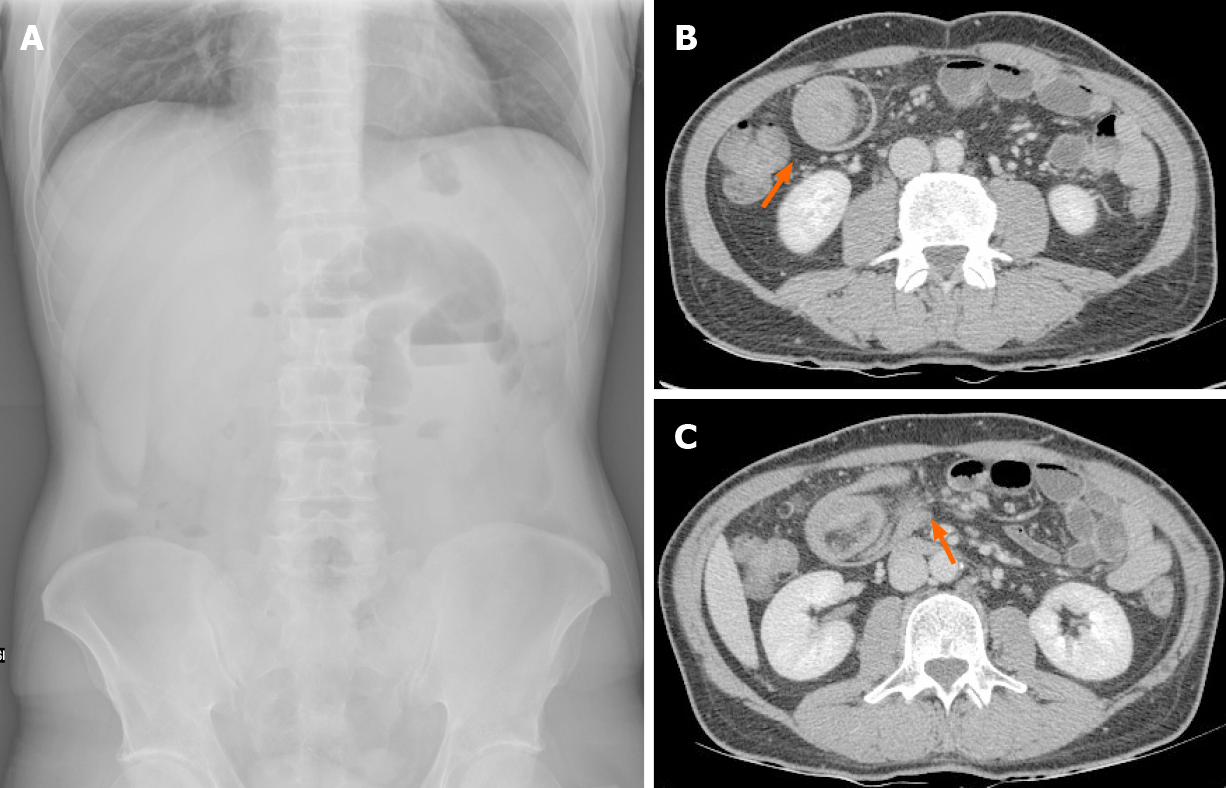

The abdomen X-ray (Figure 1) may reveal signs of intestinal obstruction (hydro-air levels, distension of the intestinal tract upstream, unexplained masses) which can occur in different abdominal quadrants depending on the level of obstruction (high or low)[20].

An upper gastrointestinal contrast entero-X-ray may show a "stacked coin" or "coil-spring" appearance, while the lower gastrointestinal contrast entero-X-ray, useful in patients with colic or ileus-colic obstruction, may show a “cup-shaped” filling defect or “spiral” or “coil-spring” appearances[20].

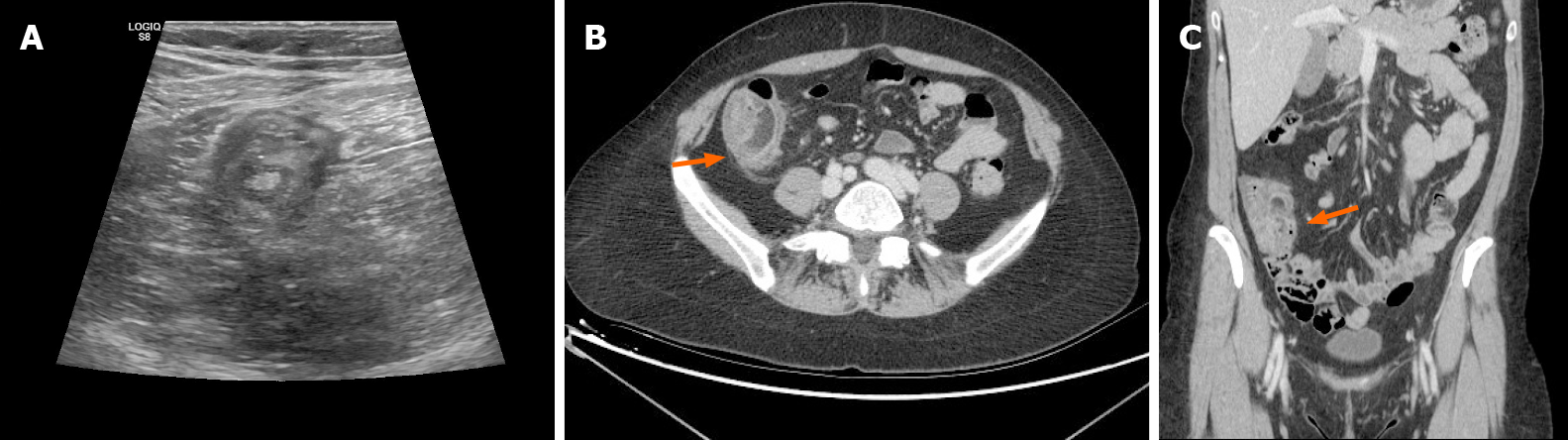

Another useful tool is ultrasound, a methodical operator dependent, which can show signs such as the “target” or “doughnut” in the transverse scans (Figure 2), or the "pseudo-kidney" sign or "hay-fork" sign in the longitudinal view[21].

CT is currently considered the gold standard for the intussusception diagnosis. Very sensitive, it can highlight the position, the nature of the mass and the relationship with the surrounding tissues[20].

The CT scan may help to find a lead-point intussusception that can be localized in the all bowel tract. The CT scan can also demonstrate some pathognomonic radio

As previously reported, adult’s intussusception is frequently cause by a pathologic lead point. For those reasons, treatment of bowel intussusception causing obstruction has typically involved surgery, often with bowel resection, as opposed to the pediatric population. The attempt of hydrostatic reduction in the adult population is not indicated; on the contrary, in the pediatric population this is the treatment of choice in the majority of cases; in fact, in this latter group of age the percentage of surgical treatment is so far less the 10% of the reported cases[22].

In recent series and retrospective review articles[23-26], the evidence that the increased use of cross sectional imaging such as CT has resulted in increment of the radiological diagnosis of intussusception, with a successful nonoperative management in many cases, has led to some degree of controversy regarding optimal management of these patients.

The main issues in the management of adult intussusception are: (1) When proceed with surgical exploration; (2) Once the surgical approach is the treatment of choice, whether attempt intraoperatively reduction or proceed direct to resection of the affected segments; and (3) Once the surgical approach is the treatment of choice, it should be performed open or laparoscopically.

In the most recent review article is reported that surgical exploration is the treatment of choice in case of: (1) Patients with signs and symptoms of acute abdomen; in this scenario abdominal exploration is the gold standard when symptoms of clinical obstruction are reported in association with radiological signs of obstruction, dehydration and increase of white blood cells along with inflammatory markers at laboratory tests; emergency exploration is mandatory in presence of signs of septic shock and peritonism (conditions almost always suggestive of intestinal ischemia); (2) Patients with diagnosis of intussusception with a mass visible on CT scan, also in the absence of clear clinical signs of acute abdomen; and (3) Patients with diagnosis of colonic or ileocolic intussusception, usually associate with neoplasm, also in the absence of clear clinical signs of acute abdomen. In these setting, preoperative endoscopy can be done in order to confirm the presence of pathology and/or cancer[8].

On the other side, many reports suggest a “wait and see” strategy, with serial clinic and imaging evaluation to ensure spontaneous resolution in entero-enteric intus

Undoubtedly, other controversy remains as to whether reduction of the intus

This controversy is related to the consideration that reducing the intussusception before resection carries risks of perforation and the theoretical possibility of dissemination of malignant cells during the attempt. The other theoretical risks of preliminary manipulation and reduction of an intussuscepted bowel is related to the endangerment of anastomotic complications of the manipulated friable and edematous bowel tissue[16,20].

On the other hand, the reduction of bowel intussusception is useful both to preserve important lengths of small bowel and to prevent possible development of short bowel syndrome, especially when the small bowel is the only tract involved because of its lower rate of association to malignancy[29,30].

On this point, we suggest that simple reduction is acceptable in post-traumatic or idiopathic intussusceptions, where no pathological cause could be identified, obviously after the exclusion of bowel ischaemia or perforation, especially in case of small bowel intussusception. Considering the high rate of primary adenocarcinoma, colonic intussusception should be resected en bloc without reduction to avoid potential intraluminal seeding or venous tumor dissemination: a formal resection using appropriate oncologic techniques are recommended, with the construction of a primary anastomosis between healthy and viable tissue. Finally, a selective approach seems appropriate for ileocolic adult intussusception because of its intermediate nature between enteric and colonic sites[11,12,31].

The choice of preforming laparoscopic rather than open procedure depends both on the clinical condition of the patient and on surgeon’s laparoscopic experience[8,27].

A standardized laparoscopic technique to approach intussusception is not available, due to the all different possible causes and locations, some tips and tricks are reported in literature[8,32,33]: the pneumoperitoneum establishment must be performed with open laparoscopy at the umbellicum because of the high risk of bowel lesions with the Verres technique. Due to the rarity of the left-side’s intussusception is recommend to place the two additional 5-mm ports one in the left lower quadrant and the other suprapubically. If needed, other ports can be placed depending on the location of the pathology. During laparoscopy all four quadrants of the abdomen and the pelvis must be thoroughly explored; once the pathologic segment is found, it can either be resected or eviscerated and dealt with extracorporeally using small incision, depending on surgeon skill and severity of the occlusive syndrome related to intussusception. It is recommended to sample suspected fluid collections for culture as well as to biopsy suspected lesions.

Bowel intussusception in adult is a rare condition with acute onset or seldom-elusive progress. Clinicians and surgeons are not supported by designated scoring systems in this challenging diagnosis because of non-specific symptoms, and its preoperative identification is often missed or delayed. On the other hand, intussusception is a surgical emergency associated to high rates of mortality in case of delayed treatment, therefore it is important to think about this less common diagnostic possibility when facing an acute abdominal pain with sign of bowel obstruction.

The management of bowel intussusception in adult remains mainly surgical. The timing and type of approach depends on several factors such as the underlying causes, the severity of clinical presentation, the site and the length and vitality of the bowel segment involved.

Anyway, the increased use of cross sectional imaging has increased the early-diagnosis of intussusception, in many cases with a successful nonoperative manage

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medical laboratory technology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhang L S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Hutchinson J. A successful patient of abdominal section for intussusception. Proc R Med Chir Soc. 1873;7:195-198. |

| 2. | Manouras A, Lagoudianakis EE, Dardamanis D, Tsekouras DK, Markogiannakis H, Genetzakis M, Pararas N, Papadima A, Triantafillou C, Katergiannakis V. Lipoma induced jejunojejunal intussusception. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3641-3644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Begos DG, Sandor A, Modlin IM. The diagnosis and management of adult intussusception. Am J Surg. 1997;173:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hanan B, Diniz TR, da Luz MM, da Conceição SA, da Silva RG, Lacerda-Filho A. Intussusception in adults: a retrospective study. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:574-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Onkendi EO, Grotz TE, Murray JA, Donohue JH. Adult intussusception in the last 25 years of modern imaging: is surgery still indicated? J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1699-1705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Honjo H, Mike M, Kusanagi H, Kano N. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. World J Surg. 2015;39:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg. 1997;226:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marsicovetere P, Ivatury SJ, White B, Holubar SD. Intestinal Intussusception: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zubaidi A, Al-Saif F, Silverman R. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1546-1551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ghaderi H, Jafarian A, Aminian A, Mirjafari Daryasari SA. Clinical presentations, diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception, a 20 years survey. Int J Surg. 2010;8:318-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang LT, Wu CC, Yu JC, Hsiao CW, Hsu CC, Jao SW. Clinical entity and treatment strategies for adult intussusceptions: 20 years' experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1941-1949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hong KD, Kim J, Ji W, Wexner SD. Adult intussusception: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:315-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brill A, Lopez RA. Intussusception In Adults. 2020 Dec 7. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. [PubMed] |

| 14. | VanderKolk WE, Snyder CA, Figg DM. Cecal-colic adult intussusception as a cause of intestinal obstruction in Central Africa. World J Surg. 1996;20:341-343; discussion 344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lu T, Chng YM. Adult intussusception. Perm J. 2015;19:79-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marinis A, Yiallourou A, Samanides L, Dafnios N, Anastasopoulos G, Vassiliou I, Theodosopoulos T. Intussusception of the bowel in adults: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:407-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Mrak K. Uncommon conditions in surgical oncology: acute abdomen caused by ileocolic intussusception. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;5:E75-E79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sarma D, Prabhu R, Rodrigues G. Adult intussusception: a six-year experience at a single center. Ann Gastroenterol. 2012;25:128-132. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Reijnen HA, Joosten HJ, de Boer HH. Diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception. Am J Surg. 1989;158:25-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Eisen LK, Cunningham JD, Aufses AH Jr. Intussusception in adults: institutional review. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:390-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Boyle MJ, Arkell LJ, Williams JT. Ultrasonic diagnosis of adult intussusception. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:617-618. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Lee EH, Yang HR. Nationwide Population-Based Epidemiologic Study on Childhood Intussusception in South Korea: Emphasis on Treatment and Outcomes. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2020;23:329-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim YH, Blake MA, Harisinghani MG, Archer-Arroyo K, Hahn PF, Pitman MB, Mueller PR. Adult intestinal intussusception: CT appearances and identification of a causative lead point. Radiographics. 2006;26:733-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rea JD, Lockhart ME, Yarbrough DE, Leeth RR, Bledsoe SE, Clements RH. Approach to management of intussusception in adults: a new paradigm in the computed tomography era. Am Surg. 2007;73:1098-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lvoff N, Breiman RS, Coakley FV, Lu Y, Warren RS. Distinguishing features of self-limiting adult small-bowel intussusception identified at CT. Radiology. 2003;227:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jain P, Heap SW. Intussusception of the small bowel discovered incidentally by computed tomography. Australas Radiol. 2006;50:171-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lianos G, Xeropotamos N, Bali C, Baltoggiannis G, Ignatiadou E. Adult bowel intussusception: presentation, location, etiology, diagnosis and treatment. G Chir. 2013;34:280-283. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Potts J, Al Samaraee A, El-Hakeem A. Small bowel intussusception in adults. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:11-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Erbil Y, Eminoğlu L, Caliş A, Berber E. Ileocolic invagination in adult due to caecal carcinoma. Acta Chir Belg. 1997;97:190-191. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Yalamarthi S, Smith RC. Adult intussusception: case reports and review of literature. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:174-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Barussaud M, Regenet N, Briennon X, de Kerviler B, Pessaux P, Kohneh-Sharhi N, Lehur PA, Hamy A, Leborgne J, le Neel JC, Mirallie E. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusceptions: a multicentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:834-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Alonso V, Targarona EM, Bendahan GE, Kobus C, Moya I, Cherichetti C, Balagué C, Vela S, Garriga J, Trias M. Laparoscopic treatment for intussusception of the small intestine in the adult. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:394-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hackam DJ, Saibil F, Wilson S, Litwin D. Laparoscopic management of intussusception caused by colonic lipomata: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1996;6:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |