Peer-review started: February 12, 2019

First decision: March 15, 2019

Revised: April 1, 2019

Accepted: April 8, 2019

Article in press: April 8, 2019

Published online: June 28, 2019

Processing time: 140 Days and 12.9 Hours

Atheroembolic renal disease (AERD) is caused by occlusion of the small renal arteries from embolized cholesterol crystals arising from ulcerated atherosclerotic plaques. This usually manifests as isolated renal disease or involvement from systemic atheroembolic disease. Here we report a case of AERD that responded well to steroid therapy.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and stage IIIa chronic kidney disease was referred for rapidly worsening renal function over a 4-mo period. She complained of swollen legs, dyspnea on exertion, and two episodes of epistaxis about a month prior to admission. She reported no history of invasive vascular procedures, use of radio contrast agents, or treatment with anticoagulants or thrombolytic agents. Urinalysis showed a few red blood cells and granular casts. Serology was positive for cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA). Non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed diffuse atherosclerotic changes in the aortic arch. Thus, c-ANCA-associated vasculitis was suspected, and the patient was started on pulse intravenous methylprednisolone. Her renal biopsy showed evidence of AERD. She was discharged with oral prednisone, and her renal function continued to improve during the initial follow-up.

In cases of non-vasculitis-associated ANCA, a high degree of clinical suspicion is required to pursue the diagnosis of spontaneous AERD in patients with clinical or radiological evidence of atherosclerotic burden. Although no specific treatment is available, the potential role of statins and steroids requires exploration.

Core tip: Spontaneous atheroembolic renal disease (AERD) is a rare clinical entity. The role of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) in atheroembolic diseases remains to be elucidated. Here, we report a case of rapidly progressive renal failure initially managed as cytoplasmic-ANCA associated renal disease but subsequently diagnosed as AERD with renal biopsy that responded surprisingly well to steroid therapy in a 62-year-old female patient. The patient was discharged with oral prednisone, and her renal function continued to improve during the initial follow-up. Although no specific treatment is available, the potential role of steroids requires exploration.

- Citation: Piranavan P, Rajan A, Jindal V, Verma A. A rare presentation of spontaneous atheroembolic renal disease: A case report. World J Nephrol 2019; 8(3): 67-74

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v8/i3/67.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v8.i3.67

Atheroembolic renal disease (AERD) is an important yet underdiagnosed kidney disease that remains in need of further research. It can manifest as isolated renal disease or as a part of systemic atheroembolic disease[1]. AERD is caused by occlusion of the small arteries in the kidneys due to embolizing cholesterol crystals arising from ulcerated atherosclerotic plaques[2]. AERD generally occurs in patients aged > 60 years and generally complicates widespread atherosclerosis[3]. Increased invasive proce-dures, awareness, and patient longevity with atherosclerotic vascular disease as well as routine use of thrombolytic and anticoagulants in clinical practice are some of the main reasons behind the increase in incidence of AERD[4,5].

Although 60%-80% of cases occur following invasive procedures like angiography or vascular surgery, spontaneous cases are not uncommon[3,6]. Studies have shown poor renal outcomes and patient survival rates associated with AERD[3]. The dialysis requirement in AERD is variable per several studies as 37%-61%[2,7]. Moreover, the 1-year reported mortality rate associated with AERD is very high and variable at 13%-81%[8,9]. Here we report a case of rapidly progressive renal failure initially managed as cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA) associated renal disease but subsequently diagnosed as AERD that responded surprisingly well to steroid therapy.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIa chronic kidney disease (CKD) was referred to our hospital for rapidly worsening renal function with hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis. Her baseline creatinine level was 1.5 mg/dL but had increased to 5.62 mg/dL over a period of 4 mo.

She has noticed bilateral lower-extremity edema and dyspnea on exertion 2 wk prior to the presentation. She denied any hemoptysis, chest pain, nausea, or vomiting. She had two episodes of epistaxis about a month prior to admission. She had two admissions over the prior 6 mo for hypertensive encephalopathy and influenza pneumonia with hypoxemic respiratory failure. There was no history of any invasive vascular procedures, use of radio-contrast agents, or treatment with anticoagulants or thrombolytic agents.

Her relevant medical history included poorly controlled hypertension, hyperli-pidemia, transient ischemic attack (TIA), diastolic heart failure, reactive airway disease, nephrolithiasis status post-lithotripsy, and osteoarthritis with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug usage.

She reported no family history of renal disease or thrombosis. She was a non-smoker and not a current alcohol user.

Her vitals were within normal limits and physical exam was normal except for bilateral lower-extremity edema and diminished breath sounds at the lung bases.

Laboratory examination revealed normocytic normochromic anemia, serum eosino-philia (10%), hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, elevated creatinine (5.2 mg/dL), and elevated blood urea nitrogen (69 mg/dL). Urinalysis showed few red blood cells (RBCs), granular casts, and microalbuminuria and was negative for eosinophil and red cell casts. Serology was positive for antineutrophil antibody, anti-cardiolipin IgM antibody, and c-ANCA; 1:320.

Liver function tests, troponins, creatinine kinase, serum magnesium, calcium, HbA1c, complement levels (C3, C4), serum immunoglobulin levels, coagulation studies including prothrombin time, protein C, S levels/activity, antithrombin III activity, and lupus anticoagulant were within normal limits. Additionally, D-dimer was positive, and factor V Leiden mutation was negative.

Her perinuclear ANCA, atypical pANCA, anti-histone antibodies, anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies, anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies, myeloma panel (serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofluorescence), viral panel (hepatitis B, C; HIV serology), and urine toxicology tests were negative.

A retroperitoneal ultrasound showed diffuse cortical thinning suggestive of medical renal disease but negative for obstructive uropathy. Non-contrast-enhanced com-puted tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was unremarkable except for diffuse atherosclerotic changes in the aortic arch. An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm, without any significant ischemic changes. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed a normal ejection fraction and was negative for atrial myxoma, vegetation, or intracardiac thrombi.

She was clinically volume overloaded and had no oliguria. She responded well with good urine output to intravenous diuretics. Hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis were improved upon initial medical management. In the background of rapidly worsening renal function with a positive titer of ANCA and history of epistaxis, ANCA-associated vasculitis was suspected; thus, she was started on pulse therapy of IV methylprednisolone 1 g/d. A renal biopsy was postponed to day 4 after admission due to relative contraindications such as aspirin usage, poorly controlled hyperten-sion, and the patient’s inability to assume a prone position due to body habitus. Once she was medically optimized, an interventional radiologist performed the renal biopsy under anesthesia. She was discharged with prednisone 60 mg because the biopsy report was not yet available at the time of discharge.

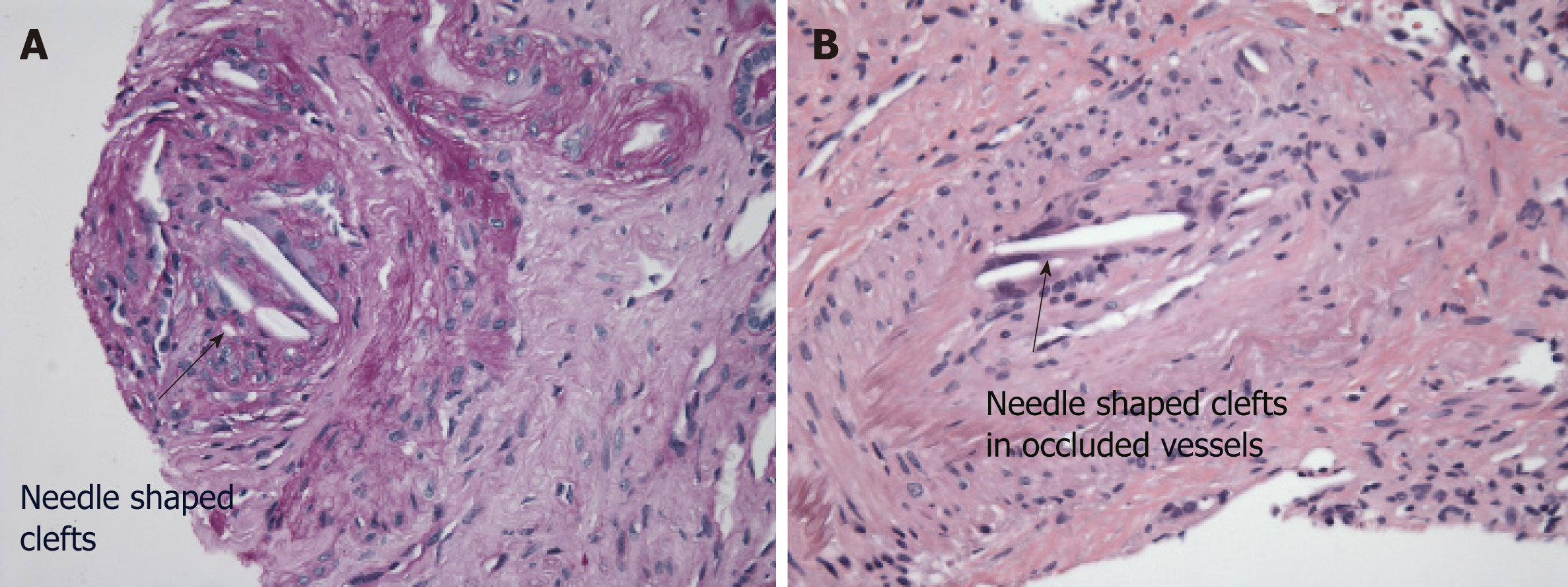

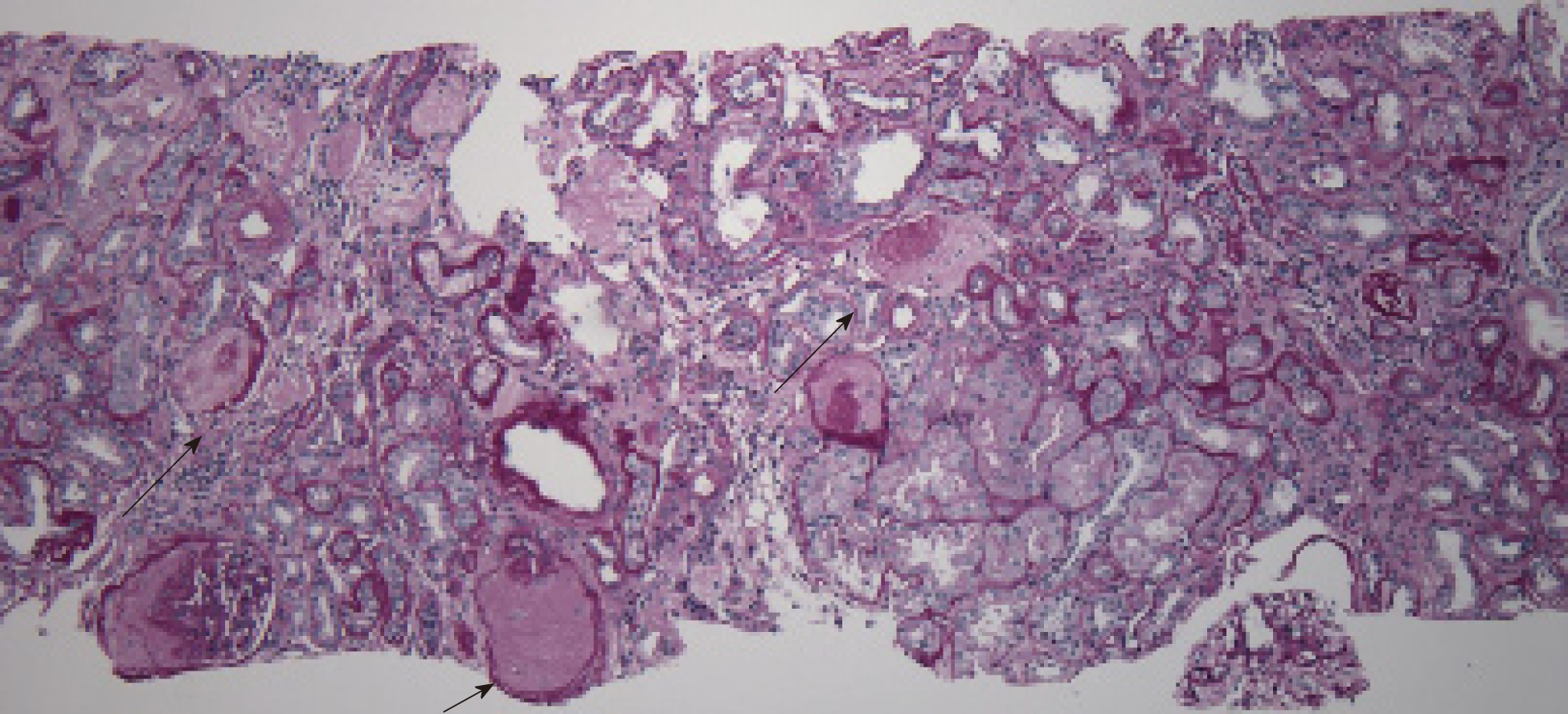

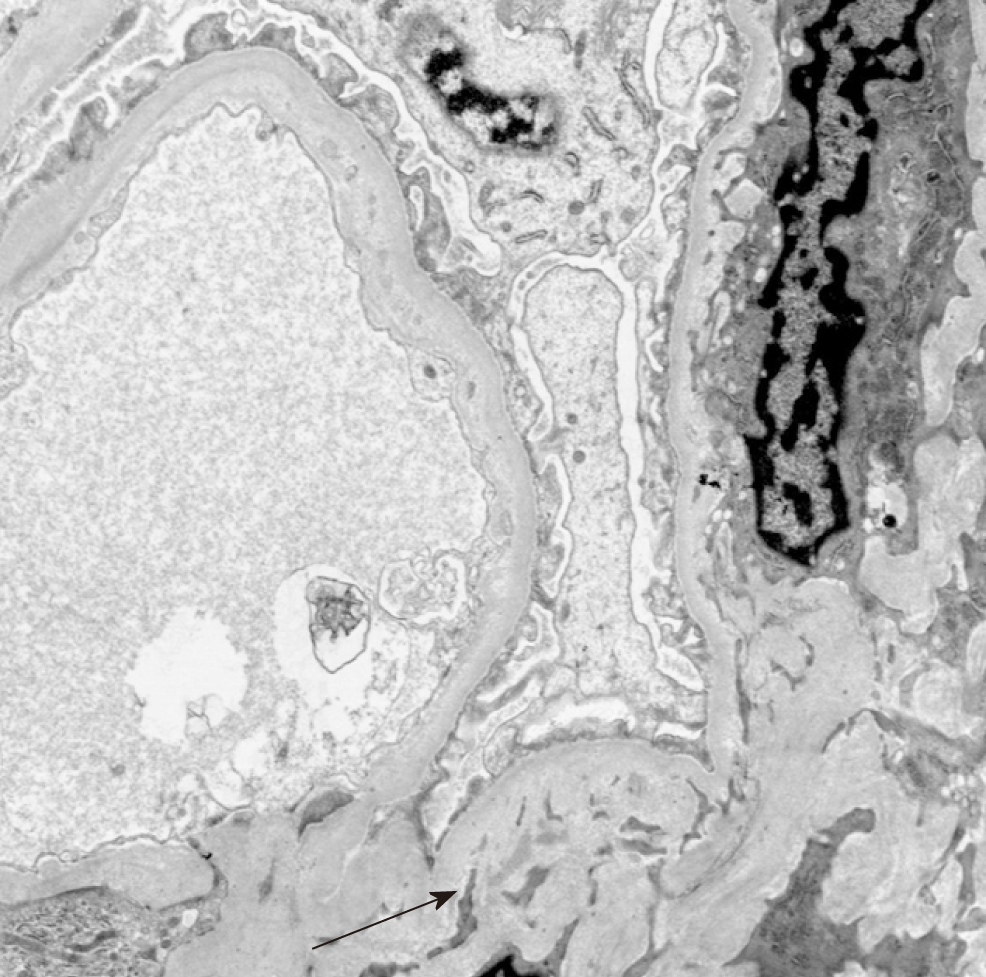

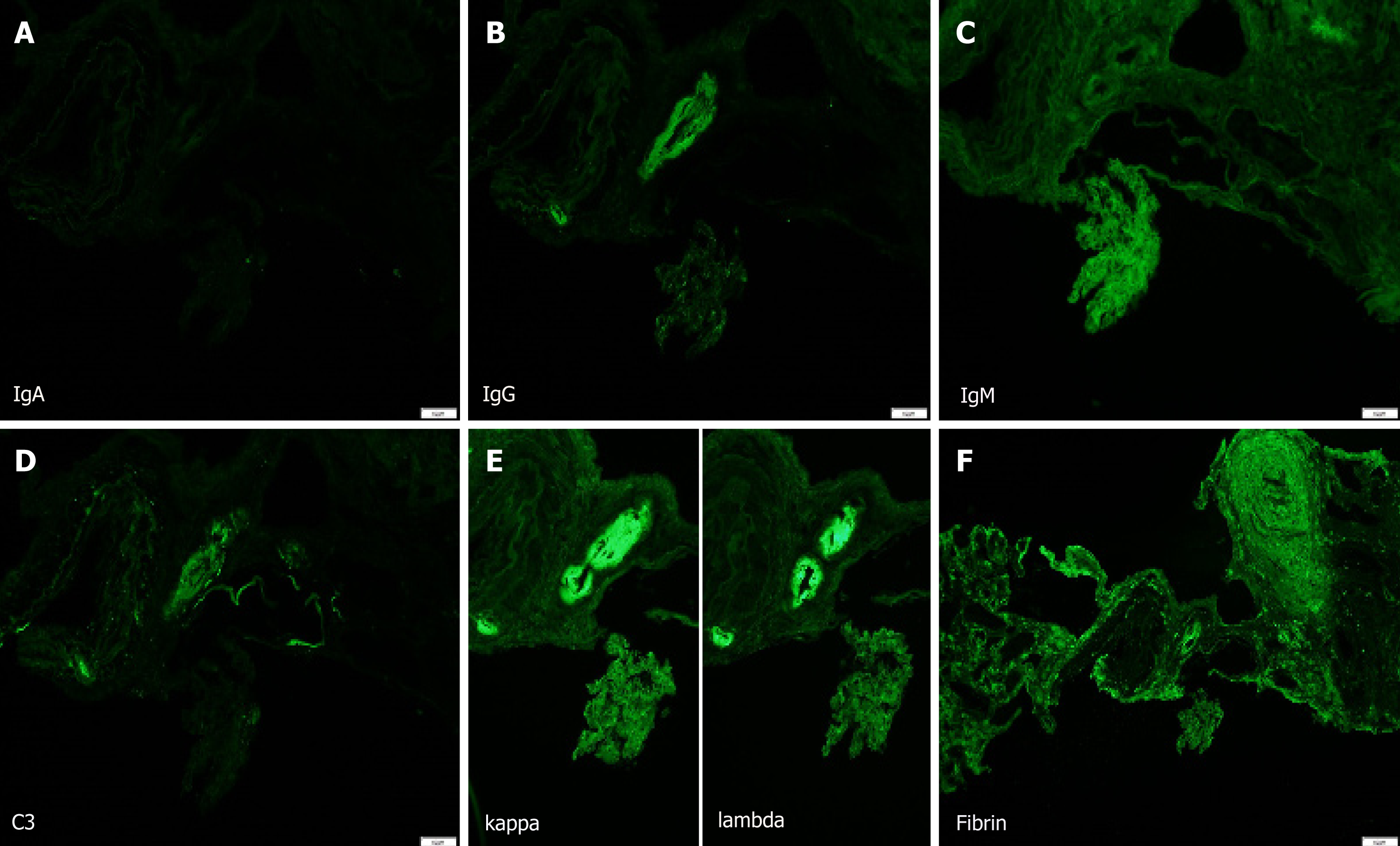

AERD. The biopsy showed major pathology of atheroembolic kidney with minimal acute tubular necrosis (ATN) that was negative for glomerulonephritis (Figure 1-4).

There is no specific treatment for AERD; rather, care is generally supportive. The aspirin and statin that she was on for risk factor control for prior TIA were continued upon discharge. Due to her steroid responsiveness as shown in isolated case reports in the past, prednisone 40 mg was continued with the intention of a slow taper.

Her renal function continued to improve, and the serum creatinine level had declined to 2.9 mg/dL at the 1-mo follow up. An ANCA test repeated twice after her 1-mo follow-up visit was negative.

Rapidly worsening renal function in a patient with pre-existing CKD can be cha-llenging, especially when the differentials are broad. In our patient, the differentials were broad, initially including all pre-, intra-, and post-renal causes. The normal retroperitoneal ultrasound excluded post-renal obstructive uropathies. She had a recent hospital admission within the previous few months for pneumonia, but there were no documented hypotensive, sepsis, or cardiorenal episodes to suggest a pre-renal cause. Intra-renal etiologies include glomerular disease, tubular disease, interstitial pathologies, and vascular disease including medium-vessel vasculitis and thrombotic microangiopathies. History and physical exam findings were not strongly supportive of any of the above.

Although ANA tested positive, she had no other manifestations of lupus including renal biopsy evidence. She had a positive c-ANCA titer with a history of recurrent hematemesis but no significant hematuria, proteinuria, or dysmorphic RBCs; urinalysis revealed bland sediments. However, based on a high degree of clinical suspicion of ANCA-associated vasculitis, she was started on steroid pulse therapy. The biopsy confirmed predominant AERD pathology, and the presence of serum eosinophilia supported the above findings. In addition, computed tomography scans showed a significant atherosclerotic burden from the aortic arch to the abdominal aorta. However, she had no history of invasive vascular procedures, anticoagulation, or hemodynamic instability prior to the initial presentation.

Although the impact of technology upon health care is immense, diagnosing AERD remains challenging[9,10]. The association between atheroembolism and ANCA positivity is exceedingly rare[11]. A recent literature review performed by Zhang et al[11] mentioned 12 cases (3 with c-ANCA, 6 with p-ANCA, 1 with both, 2 positive for ANCA by early indirect immunofluorescence) of cholesterol embolism with ANCA positivity. Of those 12 patients, the mean age was 69 years; 10 were males with multiple medical comorbidities[11]. One-third of the patients had spontaneous atheroembolism like our patient[11]. The role of ANCA in atheroembolic diseases remains to be elucidated. A positive c-ANCA result without any systemic evidence of vasculitis at the time of testing was reported previously in the literature attributed to various reasons like cross-reactivity, non-specific neutrophil-activating properties, and analytical false values[12].

Two forms of AERD have been reported[1]. Acute or sub-acute AERD manifests from a single episode or recurrent episodes of massive showering of cholesterol emboli from ruptured unstable plaques[1]. Conversely, the slow erosion of atheros-clerotic plaques leads to chronic AERD[13]. Although aortic atherosclerosis is essential for diagnosis, few patients with aortic atherosclerosis develop AERD[14,15]. Invasive angiography and vascular surgeries are the usual triggering factors for iatrogenic AERD[3,9]. Hemodynamic instability and anticoagulation contribute to spontaneous cases of AERD[6,16]. Anticoagulation leads to bleeding inside the plaque and subsequent rupture[5,17]. Mechanical trauma plays a key role, while angiography, particularly coronary angiography, is the most common iatrogenic cause[1,16]. In a good proportion (4%-13%) of cases, the disease remains idiopathic[4].

Cholesterol crystal embolization affects the skin, gastrointestinal system, kidneys, retina, lower-extremity skeletal muscles, and brain[18-20]. Two large renal biopsy studies[21,22] revealed an AERD frequency of 1%, while other studies based on autopsies of elderly patients who died after aortography or aortic surgery reported a frequency of 12%-77%[15]. Risk factors include older age, male, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and smoking[4]. It is generally associated with other atherosclerotic diseases. Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) and ATN are associated with AERD[2]. In CIN, renal function declines 1-2 d after contrast exposure[23] Conversely, in AERD, the decline in renal function is delayed, varying from days to weeks, except in a few rare cases of massive large showers of emboli[23]. Serum eosinophilia is noted up to 80% of patients with atheroembolic disease[24]. It is very challenging to differentiate atheroembolic disease from vasculitis, particularly with multi-organ involvement including skin manifestations like livedo reticularis and purple toe syndrome[2]. Chronic forms are confused with ischemic nephropathy and hypertensive nephro-pathy[2].

When the clinical triad of a precipitating event, acute or subacute renal failure, and typical skin findings is present, a biopsy is not required[9]. The presence of eosino-philia generally supports the diagnosis of AERD[1]. Histopathology usually reveals cholesterol crystal emboli as biconvex needle-shaped empty clefts identified in the lumen of arcuate and interlobular arteries[1,2]. These cells are referred to as ghost cells since they dissolve during processing[15]. Ischemic and inflammatory changes are observed in the lesions distal to the embolization[15].

Treatment is usually supportive and aims to restrict ischemic damage and prevent recurrent embolization[2]. Preventive management aims to avoid further precipitating factors, while medical intervention includes the aggressive treatment of hypertension, cardiac, renal failure, or optimal dialysis type[2]. No randomized controlled clinical trials of AERD treatment have been performed [2]. Belenfant and co-workers showed improvement in symptoms and nutritional intake with a low-dose steroid (0.3 mg/kg) in 18 patients with relapsing disease[25]. Dahlberg et al[26] and a few other studies showed the role of high-dose steroids[26]. Conversely, a prospective study of 354 patients with AERD showed no improvement in renal or patient outcomes[1]. Thus, steroid usage could play a role and may feature multi-system involvement, recurrent and progressive disease, and systemic inflammation[2]. Statins were justified with favorable outcomes in a few studies[3], and isolated reports have shown success with iloprost, pentoxifylline, and low-density lipoprotein apheresis[2] Antiplatelet agents and low molecular weight dextran have not shown a benefit[16].

Although the role of steroids is controversial, we decided to continue the steroids at a lower dose since our patient’s renal function showed significant improvement. One could argue alternative explanations like spontaneous resolution of the disease in the setting of ATN (especially when her repeat ANCA was negative at the 1-month follow-up), but further studies are needed to confirm this in the future. The high-intensity statin was continued. We have limited data regarding the sequelae of AERD and renal outcome, requirements for dialysis, and survival rates[2]. Future research is needed regarding the potential benefits of steroids and statins[2].

In summary, AERD has become a recognizable cause of acute or chronic renal failure. In cases like the above in which non-vasculitis was associated with ANCA tests, a high degree of clinical suspicion is required to pursue the diagnosis of spontaneous AERD in patients with clinical or radiological evidence of the atherosclerotic burden. No specific treatment is available, and the potential role of statins and steroids requi-res exploration.

We thank Dr Helmut G Rennke (Brigham and Woman’s Head of Pathology) for provi-ding the histopathology slides.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Al-Haggar M, Tanaka H, Yorioka N, Trimarchi H, Markic D S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wang J

| 1. | Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, Santostefano M, Rollino C, Stabellini N, Colla L, Viola BF, Maiorca P, Venturelli C, Bonardelli S, Faggiano P, Barrett BJ. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Scolari F, Ravani P. Atheroembolic renal disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1650-1660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Scolari F, Ravani P, Pola A, Guerini S, Zubani R, Movilli E, Savoldi S, Malberti F, Maiorca R. Predictors of renal and patient outcomes in atheroembolic renal disease: a prospective study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1584-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Modi KS, Rao VK. Atheroembolic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1781-1787. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Pasupala U, Soare M, Dianne S, Paixao R, Fromkin B, Berho M, Braun M. Atheroembolic Renal Disease and Anticoagulants use: A Case Report and Literature Review. World J Nephrol Urol. 2012;I:115-117. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mittal BV, Alexander MP, Rennke HG, Singh AK. Atheroembolic renal disease: a silent masquerader. Kidney Int. 2008;73:126-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ravani P, Gaggi R, Rollino C, Santostefano M, Stabellini N, Colla L, Dallera N, Ravera S, Bove S, Faggiano P, Scolari F. Lack of association between dialysis modality and outcomes in atheroembolic renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:454-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol. 1993;13:489-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fine MJ, Kapoor W, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a review of 221 cases in the English literature. Angiology. 1987;38:769-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Scoble JE, O'Donnell PJ. Renal atheroembolic disease: the Cinderella of nephrology? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:1516-1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang J, Zhang HY, Chen SZ, Huang JY. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in cholesterol embolism: A case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:1012-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Knight A, Ekbom A, Brandt L, Askling J. What is the significance in routine care of c-ANCA/PR3-ANCA in the absence of systemic vasculitis? A case series. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:S53-S56. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Polu KR, Wolf M. Clinical problem-solving. Needle in a haystack. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:68-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Flory CM. Arterial Occlusions Produced by Emboli from Eroded Aortic Atheromatous Plaques. Am J Pathol. 1945;21:549-565. [PubMed] |

| 15. | ThurlbeckWM, Castleman B. Atheromatous emboli to the kidneys after aortic surgery. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:442-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Meyrier A. Cholesterol crystal embolism: diagnosis and treatment. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1308-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Arroyo LH, Lee RT. Mechanisms of plaque rupture: mechanical and biologic interactions. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:369-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Donohue KG, Saap L, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: an atherosclerotic disease with frequent and varied cutaneous manifestations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:504-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:786-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liew YP, Bartholomew JR. Atheromatous embolization. Vasc Med. 2005;10:309-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jones DB, Iannaccone PM. Atheromatous emboli in renal biopsies. An ultrastructural study. Am J Pathol. 1975;78:261-276. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Lie JT. Cholesterol atheromatous embolism. The great masquerader revisited. Pathol Annu. 1992;27 Pt 2:17-50. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Stratta P, Bozzola C, Quaglia M. Pitfall in nephrology: contrast nephropathy has to be differentiated from renal damage due to atheroembolic disease. J Nephrol. 2012;25:282-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, Korbet SM, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Belenfant X, Meyrier A, Jacquot C. Supportive treatment improves survival in multivisceral cholesterol crystal embolism. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:840-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |