Published online Sep 6, 2016. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v5.i5.389

Peer-review started: May 3, 2016

First decision: June 17, 2016

Revised: July 29, 2016

Accepted: August 17, 2016

Article in press: August 18, 2016

Published online: September 6, 2016

Processing time: 125 Days and 1.4 Hours

In 2015, 634387 million people (9% of the world’s population) resided in Latin America (LA), with half of those populating Brazil and Mexico. The LA Dialysis and Transplant Registry was initiated in 1991, with the aim of collecting data on renal replacement therapy (RRT) from the 20 LA-affiliated countries. Since then, the Registry has revealed a trend of increasing prevalence and incidence of end-stage kidney disease on RRT, which is ongoing and is correlated with gross national income, life expectancy at birth, and percentage of population that is older than 65 years. In addition, the rate of kidney transplantation has increased yearly, with > 70% being performed from deceased donors. According to the numbers reported for 2013, the rates of prevalence, incidence and transplantation were (in patients per million population) 669, 149 and 19.4, respectively. Hemodialysis was the treatment of choice (90%), and 43% of the patients undergoing this treatment was located in Brazil; in contrast, peritoneal dialysis prevailed in Costa Rica, El Salvador and Guatemala. To date, the Registry remains the only source of RRT data available to healthcare authorities in many LA countries. It not only serves to promote knowledge regarding epidemiology of end-stage renal disease and the related RRT but also for training of nephrologists and renal researchers, to improve understanding and clinical application of dialysis and transplantation services. In LA, accessibility to RRT is still limited and it remains necessary to develop effective programs that will reduce risk factors, promote early diagnosis and treatment of chronic kidney disease, and strengthen transplantation programs.

Core tip: In Latin America (LA), patients with end-stage renal disease on renal replacement therapy (RRT) are tracked by the LA Dialysis and Transplant Registry. Data from the Registry shows increasing prevalence and incidence, which are correlated with gross national income, life expectancy at birth, and percentage of population over 65 years. The Registry represents the only source of such data in many LA countries. Its contributions to the knowledge of RRT epidemiology in LA as well as to the education and training of nephrologists are highlighted in this article, and the need for its evolution towards population-based Registries is discussed.

- Citation: Cusumano AM, Rosa-Diez GJ, Gonzalez-Bedat MC. Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry: Experience and contributions to end-stage renal disease epidemiology. World J Nephrol 2016; 5(5): 389-397

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v5/i5/389.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v5.i5.389

Latin America (LA) is a conglomerate of nations sharing a common Latin ancestry and languages (mainly Spanish or Portuguese). It includes South and Central America, Mexico and the Hispanic Caribbean Islands. Multiethnic and multicultural, its population displays a great genetic diversity, resulting from multiple admixture events that occurred among the original European immigrants (mainly from Spain and Portugal but including other nationalities that arrived in large numbers during the so-called “Italian diaspora” in the late 19th and the early 20th century and also represented by those escaping the World Wars) and Native Americans (who currently represent the majority in Bolivia and very high percentages in Guatemala, Peru and Mexico) as well as the descendants of slaves that migrated from Africa (with very high numbers in Brazil in particular, and fewer in Colombia and Uruguay). The racial admixture is so robust that genetic studies arrived at the conclusion that physical appearance has poor reliability as an indicator of genetic ancestry for the LA peoples in general[1]. In Uruguay, specifically, it was reported, “the data show that almost every population is dihybrid or trihybrid, and when African influence is not detected, it is probably due more to the method than to an absence of that contribution”[2]. Thus, each Latin American country is considered to encompass its own unique ethnic characteristics.

The 2015 population estimate for LA is 634387 million (including Puerto Rico, a political territory of the Northern American-situated United States), accounting for roughly 9% of the global population[3]. Approximately one-half of the LA populations reside in Brazil and Mexico. Brazil, itself, is the biggest and most populous LA country and the 5th largest country in the world, both by geographical area and by population. LA annual growth is 1% per year, with 7.4% of its inhabitants being older than 65 years[3-5]. Approximately 8% of LA peoples identify themselves as indigenous, representing more than 522 groups dispersed broadly throughout the continent and speaking around 420 languages (e.g., Quechua, Aymara, Guarani, among others)[6,7].

LA has experienced significant social and financial progress over the past decades; however, the improvements have happened in an inequitable way, contributing to striking disparities in health and economic conditions among social classes and geographic regions, between countries as well as within countries. As a result, LA is currently characterized by the Gini index (which describes how far away a country’s income distribution is from complete equality) as having the highest socioeconomic inequality in the world. As a whole, however, socioeconomic indexes of LA countries have improved throughout the current century.

Gross national income (GNI) per capita (as calculated by the Atlas method) increased from an average of 3300 USD to 9941 USD between 2000 and 2014, but ranging from 830 USD in Haiti to 19210 USD in Puerto Rico[5]. Most of the LA countries have reached the status of upper middle income (4126 USD to 12735 USD), including Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Panamá, Paraguay and Peru. Only one country - Haiti - qualifies as a low-income country (< 1045 USD). Five countries are included in the group of low middle income (1046 USD to 4125 USD; Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua), and five are included in the group of high income (> 12736 USD; Argentina, Chile, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Venezuela)[8].

Life expectancy at birth has also shown an increasing trend in LA countries, from 70 years in 2000 to 75.5 years in 2015, approaching the observed indexes of more developed nations[3]. LA countries have seen increases in life expectancy, with Chile having the highest (80 years) and with Bolivia (67.8 years) and Haiti (62.6 years) having lower proportions of increase compared to the other countries. The overall improvement has been achieved largely through a reduction in child mortality. In contrast, the percentage of people living below the poverty line in LA countries continues to be high (28.1% in 2013), as does the percentage of people leaving under the line for extreme poverty (11.7%)[3]. Finally, the human development index (HDI; an indicator of the quality of life of a country, defined by the United Nations Development Program and which combines the three basic dimensions of life expectancy at birth, education and income per capita) is 0.748 for LA countries as a whole, but ranges from as low as 0.484 in Haiti to very high in Argentina (0.836) and Chile (0.832)[9].

Eighty percent of the populations of LA countries reside in urban areas, making LA the most urbanized region in the world[10]. The rate of urbanization ranges from 53.6% in Honduras to 91.8% in Argentina. Moreover, approximately 24% of LA inhabitants of large cities live in slum neighborhoods. More than 60 cities in LA have recorded populations of > 1 million inhabitants, including several cities that are characterized as megalopolis (defined as more than 10000000 people, including neighborhoods), such as San Pablo (Brazil), Mexico City (Mexico), and Buenos Aires City (Argentina)[3,10,11]. Over the past few decades, the population pyramid has changed its shape into that of a bell, reflecting its evolution towards that of an aging society in general. All of these features of the peoples residing in LA countries present new challenges to each country’s healthcare system, which remain under the burden of ongoing challenges otherwise associated with lower socioeconomic regions, such as high rates of infectious diseases.

As in the rest of the world, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is prevalent throughout LA, due to both infectious disease prevalence and immature public health systems. Epidemiological information about the prevalence of early-stage CKD in the general LA population is scarce and of low quality. It is known, however, that CKD constitutes a higher burden in Central America, where a regional epidemic of CKD of unknown origin emerged during the last decade, affecting primarily young male agricultural workers from communities along the Pacific coast and southern México, especially sugarcane workers. In the involved areas, the national mortality rates have reached as high as 5 times the national rates, with El Salvador representing the country with the highest mortality rate from kidney disease worldwide[12,13].

Information about cardiovascular and renal risk factors is available through national health inquires in some countries; their results confirm that these risk factors are highly prevalent in LA, particularly in countries with greater percentage of inhabitants over 65-year-old, such as Argentina (11%), Brazil (7%), Chile (10%) and Uruguay (14%) (Table 1).

| Argentina | Brazil | Chile | Mexico | Uruguay | Ecuador | Paraguay | |

| Survey year | 2013 | 2013 | 2010 | 2012 | 2013 | 2013 | 2011 |

| Hypertension | 34.1 | 24.1 | 26.9 | 31.5 | 38.7 | 15.6 | 32.2 |

| High cholesterol | 29.8 | 20.3 | 38.5 | 23.9 | 24.5 | 25.5 | |

| Overweight | 37.1 | 33.3 | 39.3 | 38.8 | ND1 | ND | 34.8 |

| Overweight + Ob | 57.9 | 50.8 | 64.4 | 71.3 | 64.7 | ND | 57.6 |

| Ob | 20.8 | 17.5 | 25.1 | 32.4 | ND | 50 | 22.8 |

| Diabetes | 9.8 | 6.9 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 7.8 | ND | 9.7 |

| Current smokers | 25.1 | 11.3 | 40.6 | 19.9 | 28.8 | 25.9 | 14.5 |

| Sedentarism | 55.1 | 66.2 | 88.6 | 70 | ND | 74.5 |

Renal replacement therapy (RRT) started as peritoneal dialysis (PD) in Brazil in 1947. Shortly thereafter, the first hemodialysis (HD) was also accomplished in Brazil (in 1949), and the first kidney transplant in Argentina (in 1956)[14,15]. Initially, HD was considered exclusively as a therapy to support patients with acute renal failure and who were awaiting transplantation, but it quickly became incorporated as treatment for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The field of clinical nephrology developed almost simultaneously, with physicians and researchers consolidating into National Nephrology Societies, such as those of Argentina (in 1960), Brazil (in 1960), Chile (in 1964) and Uruguay (in 1967).

The LA Nephrology and Hypertension Society [Sociedad Latinoamericana de Nefrología e Hipertensión (SLANH)] was created in 1970, grouping the various National Nephrology Societies of 20 countries (i.e., Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Venezuela). In 1991, the SLANH founded the LA Dialysis and Transplant Registry (LADTR) to promote the knowledge and improve the care of ESRD by collects and analyzing data from the 20 member countries. The Registry office was housed in Montevideo (Uruguay) until 2001, when it moved to Buenos Aires (Argentina), where it remained until 2012, when it returned to Montevideo. Currently, the Registry is composed of an Executive Board and delegates from each of the Nephrology Societies that are part of the SLANH.

The methodology used by the LADTR has been reported previously. Briefly, participant countries complete an annual survey to provide data on incident and prevalent cases of patients undergoing RRT by means of all modalities: HD, PD, and living with a functioning graft (LFG), CKD etiology, number and type of kidney transplants, percent of population under RRT coverage, and number of nephrologists, as well as other relevant parameters. Analyses of these variables are performed routinely to determine correlations with GNI and life expectancy at birth as well as other socioeconomic indexes[16-23].

All 20 SLANH countries have and continue to participate in the annual surveys, providing data for > 90% of the LA populations since the beginning of the century. Table 2 describes the most prominent variables analyzed in the last available survey.

| Country | Population1 | GNI | LEB | Prevalence rates, pmp | Incidence rate | Kidney Tx, n | Tx by deceased donors, % | Kidney Tx rate | Nephro-logists, n | Nephro-logists, pmp | ||||

| HD | PD | Total dialysis | LFG | Total RRT | ||||||||||

| Argentina | 42202935 | 13690 | 76 | 626.6 | 36.0 | 662.7 | 197.2 | 859.9 | 160.2 | 1287 | 68.4 | 30.5 | 1150 | 27.2 |

| Bolivia | 10448913 | 2220 | 67 | 195.2 | 18.3 | 213.5 | 31.6 | 245.1 | 94.8 | 75 | 24.0 | 7.2 | 24 | 2.3 |

| Brazil | 202740000 | 11640 | 74 | 449.6 | 45.6 | 495.2 | 212.6 | 707.8 | 180.3 | 5433 | 74.7 | 26.8 | 3300 | 16.3 |

| Chile | 17819054 | 14290 | 80 | 1019.1 | 61.2 | 1080.3 | 205.1 | 1285.4 | 182.4 | 234 | 74.8 | 13.1 | 132 | 7.4 |

| Colombia | 47661787 | 7020 | 74 | 349.0 | 143.6 | 492.6 | 111.3 | 603.9 | 89.7 | 680 | 99.7 | 14.3 | 95 | 2.0 |

| Costa Rica | 4773730 | 8850 | 80 | 42.3 | 76.0 | 118.4 | 282.6 | 400.9 | ND | 105 | 48.6 | 22.0 | 24 | 5.0 |

| Cuba | 11163934 | 6051 | 79 | 259.1 | 10.1 | 269.3 | 78.4 | 347.6 | 103.1 | 174 | ND | 15.6 | 524 | 46.9 |

| Ecuador | 16100000 | 3600 | 76 | 481.8 | 48.0 | 529.8 | 20.4 | 550.2 | 177.6 | 127 | 81.1 | 7.9 | 143 | 8.9 |

| El Salvador | 6401240 | 5360 | 72 | 232.5 | 288.7 | 521.1 | 73.6 | 594.7 | 390.1 | 20 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 47 | 7.3 |

| Guatemala | 16173133 | 3130 | 72 | 157.7 | 221.3 | 379.0 | 54.0 | 433.0 | 124.8 | 90 | 13.3 | 5.6 | 54 | 3.3 |

| Honduras | 8500000 | 2140 | 73 | 186.9 | 14.4 | 201.3 | 8.4 | 209.6 | 176.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18 | 2.1 |

| Jalisco (Mexico) | 7742303 | ND | ND | 599.4 | 486.7 | 1086.1 | 567.4 | 1653.5 | 420.9 | 447 | 16.1 | 57.7 | 45 | 5.8 |

| Nicaragua | 6146000 | 1690 | 74 | 211.5 | 24.4 | 235.9 | 21.2 | 257.1 | 24.4 | 11 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 28 | 4.6 |

| Panamá | 3975404 | 9030 | 77 | 495.0 | 90.3 | 585.3 | 110.7 | 696.0 | 462.1 | 48 | 73.1 | 12.1 | 25 | 6.3 |

| Paraguay | 6783374 | 3310 | 75 | 165.7 | 4.0 | 169.7 | 19.9 | 189.6 | 20.2 | 26 | 79.0 | 3.8 | 46 | 6.8 |

| Perú | 30297279 | 5680 | 72 | 272.2 | 43.1 | 315.3 | 63.2 | 378.5 | 30.0 | 184 | 75.0 | 6.1 | 301 | 9.9 |

| Puerto Rico | 3615000 | 18370 | 79 | 1362.1 | 106.2 | 1468.3 | 378.4 | 1846.7 | 432.9 | 80 | 86.3 | 22.1 | 97 | 26.8 |

| Rep Dominicana | 12000000 | 5570 | 73 | 178.8 | 47.3 | 226.1 | 52.8 | 278.9 | 208.3 | 84 | 92.9 | 7.0 | 135 | 11.3 |

| Uruguay | 3406545 | 13670 | 77 | 692.2 | 71.6 | 763.8 | 323.5 | 1087.3 | 157.3 | 105 | 91.4 | 30.8 | 173 | 50.8 |

| Venezuela | 30389596 | 12460 | 74 | 505.1 | 0.0 | 505.1 | 60.8 | 565.9 | ND | 281 | 69.8 | 9.2 | 502 | 16.5 |

| Totals | 488340227 | 147771 | 75 | 442.0 | 67.0 | 509.0 | 159.0 | 669.0 | 149 | 9491 | 70.4 | 19.4 | 6863 | 14.0 |

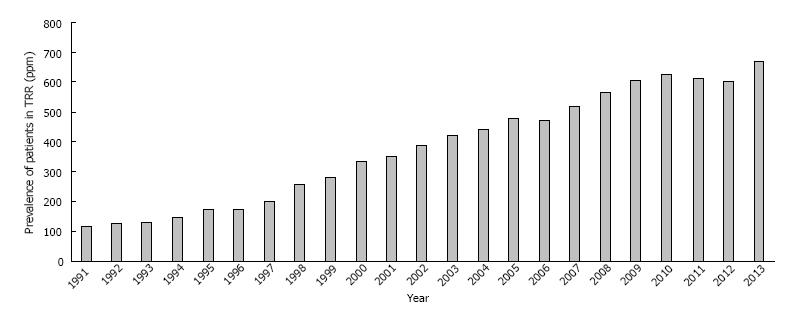

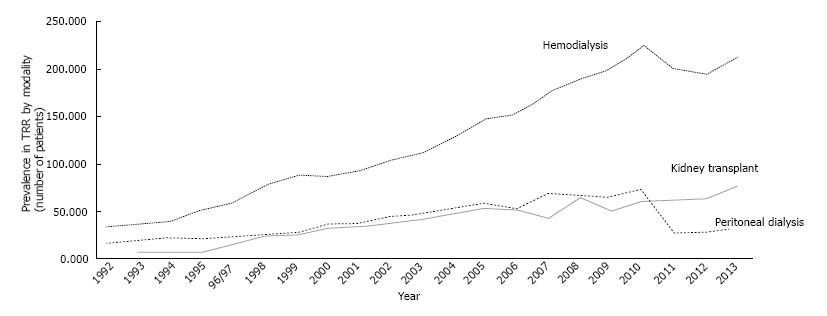

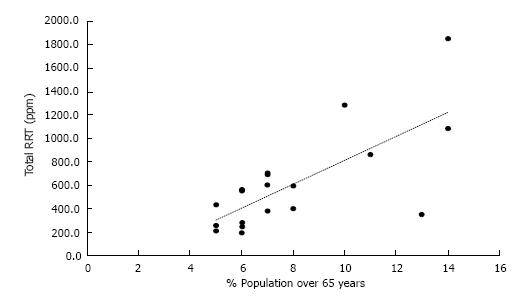

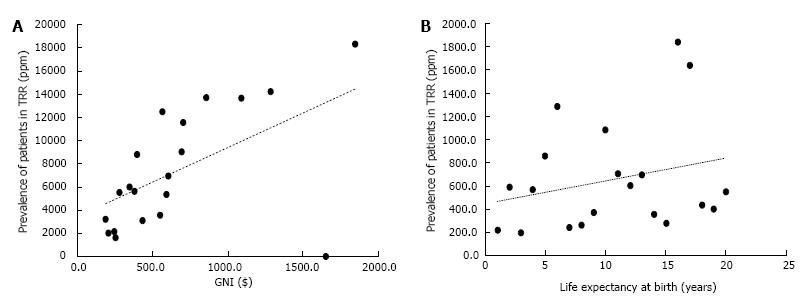

From 1991 to 2013, the prevalence of ESRD under RRT increased from 119 patients per million population (pmp) to 660 (HD, 436 pmp; PD, 67 pmp; LFG 157 pmp) (Figures 1 and 2). Only six countries have RRT prevalence above the mean: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Jalisco (Mexico), Puerto Rico and Uruguay, with the reported rates ranging from 778 pmp to 1847 pmp. The prevalence rates among the population over 65-year-old is particularly high, especially in the six countries accounting for the highest amounts of this population (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Puerto Rico and Paraguay) and reaching as high as 2400 pmp. As expected, the overall prevalence correlated with the percentage of people over 65-year-old (Figure 3). Moreover, every time it was analyzed, the prevalence correlated significantly with GNI and life expectancy at birth[16,19-21] (Figure 4).

An increase in RRT patients has occurred for all modalities, but HD in particular has proportionally increased more than PD and transplantation (Figure 2)[24]. HD continues to be the treatment of choice in the LA region (90%) and 43% of HD patients are located in Brazil. PD prevailed in 2013 only in Costa Rica (64.2%), El Salvador (55.4%) and Guatemala (58.4%). PD was also common in Colombia, although the percentage of Colombian PD patients has consistently decreased over the last years (from 54% in 2000 to 29.2% in 2013)[24].

Data for incidence of RRT were provided to the LADTR by 18/20 countries in 2013, accounting for 92.7% of the population of LA. A wide rate variation was observed, from 462.1 pmp in Panama to 20 in Paraguay. A tendency towards rate stabilization/little growth was found for most countries, except in the Central America countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Panama, which showed a significant increase in incidence. Diabetes continues to be the leading indication for dialysis. The LADTR received data on RRT incident diabetic patients from 13 countries, accounting for 84.2% of the entire LA population. The reported percentage of diabetic patients from each country ranged from 16.7% to 66.9% (mean, 37.5%). The highest diabetes incidence rates were reported by Puerto Rico (66.9%), Jalisco (Mexico) (58%) and Paraguay (45.3%), while the lowest rates were reported by Uruguay (27.7%) and Chile (16.7%) (Table 3). The overall RRT incident diabetics rate was 58 pmp, lower than that reported from the United States Renal Data System in the same year (158.4 pmp), but more than double that from the European ERA/EDTA Registry (24 pmp)[25,26]. In addition, the LADTR indicated that 19.4% of the RRT population was placed on a kidney transplant waiting list.

| Country | Population | Incident patients, n | Incident rate | Diabetics, % |

| Argentina | 42202935 | 6760 | 160.2 | 35.1 |

| Bolivia | 10448913 | 991 | 94.8 | 30.0 |

| Brazil | 202740000 | 36548 | 180.3 | 40.0 |

| Chile | 17819054 | 3250 | 182.4 | 16.7 |

| Colombia | 47661787 | 4274 | 89.7 | 33.5 |

| Ecuador | 16100000 | 2860 | 177.6 | 30.0 |

| Guatemala | 16173133 | 2018 | 124.8 | 30.0 |

| Jalisco (Mexico) | 7742303 | 3259 | 420.9 | 58.0 |

| Nicaragua | 6146000 | 150 | 24.4 | 41.6 |

| Paraguay | 6783374 | 137 | 20.2 | 45.3 |

| Peru | 30297279 | 910 | 30.0 | 32.2 |

| Puerto Rico | 3615000 | 1565 | 432.9 | 66.9 |

| Uruguay | 3406545 | 536 | 157.3 | 27.7 |

When compared with the United States data from 2013, incidence in LA, as a whole, was substantially lower (149 vs 363)[25], but when looking individual countries, Jalisco (representing Mexico), Puerto Rico, Panama and El Salvador have similar rates (421, 433, 462 and 390, respectively). When compared to the European ERA/EDTA registry (112 pmp)[26], the rate is higher in most LA countries (Table 2). Probably, there is more than one reason for the striking differences in incidence in LA, such as higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (in Mexico and Puerto Rico, in particular) (Table 2) or of CKD of unknown origin (termed as Mesoamerican Nephropathy, involving the Pacific coast and southern Mexico)[12,13], or varying access to RRT among the countries (Nicaragua and Paraguay). Overall, LA prevalence rates (660 pmp) are very far from those reported for the United States (2014 pmp) and are closer to those reported from the European ERA/EDTA (738 pmp)[24,25].

The data in the LADTR indicates that the overall kidney transplant rate increased from 3.7 pmp in 1987 to 6.9 in 1991 and then to 19.4 in 2013; although, there were remarkable disparities among the various countries in the last year: 57.7 pmp in Jalisco (Mexico), 32 pmp in Uruguay and 1.8 pmp in Nicaragua. The highest number of transplants (n = 5433) occurred in Brazil, which had a transplant rate of 26.8 pmp for 2013. A total of 244 double kidney-pancreas transplants were performed in LA in 2013: Brazil, n = 120; Argentina, n = 63; Costa Rica, n = 51; Colombia, n = 5; Uruguay, n = 3; Ecuador, n = 1; Chile, n = 1. The total number of all kidney-related transplants in 2013 was 9491, with 70.4% from cadaveric donors; the highest percentages of the latter were reported by Colombia (99.7%), Dominican Republic (92.9%) and Uruguay (91.4%).

Even though kidney transplantation is feasible, available, and an increasingly used modality for RRT in all LA countries, its growth rate is not as fast as it should be in order to compensate for the increased prevalence of patients on waiting lists for transplantation. This fact further strengthens the need to implement transplant programs and procurement of suitable organs. Moreover, the key issues identified in this study - specifically, the increased incidence of patients in RRT for all modalities in the LA region, and diabetes continuing to be the leading clinical cause for RRT - highlight the crucial nature of prevention programs for CKD to achieve early diagnosis and treatment. Yet, there is a wide gap in the amount of nephrologists among each LA country (from 2 pmp in Colombia to 50.8 pmp in Uruguay) that must be taken into consideration.

Since its creation, the LADTR has fulfilled its mission, providing valuable information on epidemiology and burden of ESRD under RRT in the region and correlating the data with socioeconomic indexes. The results of the LADTR annual surveys have been published, providing consistent data and trends about ESRD under RRT and national variations inside the region, thereby transforming the registry into a powerful tool for health authorities and highlighting the necessity of guaranteeing full access to RRT while establishing transplantation and procurement programs[16-24]. In addition, the observation that the primary etiologies of ESRD are preventable (i.e., diabetes and kidney hypertensive disease) has prompted the development of National Clinical Practice Guidelines for CKD Diagnosis and Treatment and the creation of programs aimed at accomplishing early detection and treatment. Recently, based upon the work of the LADTR, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) included in its Strategic Plan a specific target for ESRD treatment - namely, to reach, by the year 2019, a RRT prevalence of, at least, 700 pmp for all ESRD cases in all LA countries[27]. To achieve this objective, the PAHO estimates at least 20 nephrologists pmp will be needed in each country.

Moreover, the LADTR, through its participation in National, LA, Hispanic American and International Congresses and Meetings and in the International Society of Nephrology Kidney Health in Disadvantaged Populations Committee, has contributed to spreading knowledge of the epidemiology of RRT throughout the nephrology community in the LA region, and to enable productive comparisons with the rest of the world. The LADTR has also stimulated the development of voluntary and obligatory national renal registries. At present, 10 countries have consolidated national registries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Puerto Rico, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela; some of these were initiated in the 1980s, such as the Chilean (1980) and the Uruguayan (1981) ones, so that they are providing a rich database of information today[28].

The LADTR has simultaneously improved the training of nephrologists in epidemiology, having organized, in conjunction with the European ERA/EDTA Registry, the Introductory Course in Epidemiology in Buenos Aires (2007, Argentina), Mexico City (2009, Mexico) and Cartagena de Indias (2011, Colombia). It is appropriate to recognize, here, the permanent collaboration of the Spanish Society of Nephrology, in particular its fellowship program for Latin Americans, which has allowed young nephrologists to train abroad.

The continuity of the LADTR along the years, whose members participate without any fee, has implied a sustained effort of the entire Latin American nephrology community.

The LADTR recognizes several limitations. In most Latin American countries, reporting to the registry is not mandatory, not all the countries report all the data each year, data are collected from each country on a global basis, and, in the past, data from some province or region have been extrapolated to the whole country. This last feature was the case for Mexico, wherein prevalence and incidence were extrapolated from the data of the Mexican states of Jalisco and Morelos until the year 2010; moreover, since 2011, only the data from Jalisco has been deposited in the LADTR. Furthermore, the LADTR cannot report survival data for any of its participating countries, as it currently collects only aggregated data. Finally, the number of LFG patients in many countries is estimated and not definitive.

In spite of its limitations, the LADTR has provided current knowledge about trends of RRT prevalence and incidence in a defined geographical zone (LA) and in defined countries (the 20 that comprise the SLANH), has shown that, in part, the increase in incidence is related to the expansion of the burden of kidney diabetic disease, and has revealed the striking differences in prevalence and incidence that are associated with the countries’ wealth status and health coverage.

Heterogeneity or even the absence of registries in some Latin American countries is congruent with the inequities in access to RRT in such countries, as well as the limited availability of skilled human resources. The inclusion by the PAHO Strategic Plan of a goal of 700 pmp under RRT by 2019 undoubtedly will contribute to increased health coverage and the implementation of obligatory national registries, all of which, added to the sustained contribution of the nephrology community, will undoubtedly result in improved quality of national-based registries and the LADTR itself, supporting the development of population-based registries.

The LADTR has sustained its continuity over the years and, at present, it is the only source of data about RRT in the region and for many of its member countries. Its future depends on the quality of its data, which in turn depends on the data provided by the respective national registries and their (and its) quality control procedures. To continue its tasks, in the future, the LADTR will likely require funding that is sufficient to strengthen quality-controlled data.

Since its creation in 1991, the LADTR has provided valuable information on epidemiology and burden of ESRD under RRT and continues to be, at present, the only source of RRT data for this region. Prevalence and incidence of RRT continue to increase throughout LA. Prevalence correlates with GNI, life expectancy at birth and percentage of the population over 65-year-old. In the LA region, as a whole, it is still necessary to increase full accessibility to RRT and to develop programs that will facilitate better control of risk factors and early diagnosis and treatment of CKD, as well as implementation of effective transplantation programs.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country of origin: Argentina

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Disthabanchong S, Friedman EA, Martinez-Castelaoa A, Simone G S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Sans M. Admixture studies in Latin America: from the 20th to the 21st century. Hum Biol. 2000;72:155-177. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ruiz-Linares A, Adhikari K, Acuña-Alonzo V, Quinto-Sanchez M, Jaramillo C, Arias W, Fuentes M, Pizarro M, Everardo P, de Avila F. Admixture in Latin America: geographic structure, phenotypic diversity and self-perception of ancestry based on 7,342 individuals. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Statistical yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean 2015 (LC/G.2656-P), Santiago, 2015. ISBN 978-92-1-057526-3 (pdf). Available from: http://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/39867/S1500739_mu.pdf?sequence=1. |

| 4. | Health situation in the Americas. Basic Indicators 2015. Available from: http://www.paho.org//hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&indicadores paho. |

| 5. | The World Bank Group. World Bank Indicators. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD/countries?display=graphsumano. |

| 6. | UNICEF. Atlas sociolinguistico de pueblos indigenas de America latina. Primera edición 2009. ISBN 978-92-806-4491-3. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/ecuador/Atlas_Sociolinguistico_LAC.pdf. |

| 7. | Indigenous Latin America in the Twenty-First Century. The first decade. The World Bank. 2015. Indigenous Latin America in the Twenty-First Century. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO. Available from: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2016/02/03/090224b08413d2d2/3_0/Rendered/PDF/Indige nous0Lat0y000the0first0decade.pdf. |

| 8. | The World Bank Group. World Bank New Country Classifications. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/news/new-country-classifications-2015. |

| 9. | United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2015. ISBN 978-92-1-126398-5, eISBN 978-92-1-057615-4. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2015_human_development_report_1.pdf. |

| 10. | United Nations. State of the World’s Cities. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/745habitat.pdf. |

| 11. | United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects 2014. Available from: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2014-Highlights.pdf. |

| 12. | Correa-Rotter R, Wesseling C, Johnson RJ. CKD of unknown origin in Central America: the case for a Mesoamerican nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:506-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wesseling C, Crowe J, Hogstedt C, Jakobsson K, Lucas R, Wegman DH. The epidemic of chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Mesoamerica: a call for interdisciplinary research and action. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1927-1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lugon JR, Cusumano AM, Strogoff de Matos JP, Cueto Manzano AM. The developing of Dialysis in Latin America. Dialysis: History, Development and Promise. In: Ing TS, Rahman MA, Kjellstrand CM, editors. Singapore: World Scientific 2012; 621-630. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Lanari A, Rodo JE, Molins M, Torres Agüero M, Garcés JM, Martin R. [Human kidney homograft. Experience with 100 grafts]. Medicina (B Aires). 1978;38:1-8. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Mazzuchi N, Schwedt E, Fernández JM, Cusumano AM, Anção MS, Poblete H, Saldaña-Arévalo M, Espinosa NR, Centurión C, Castillo H. Latin American Registry of dialysis and renal transplantation: 1993 annual dialysis data report. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2521-2527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | González-Martínez F, Agost-Carreño C, Silva-Ancao M, Elgueta S, Cerdas-Calderón M, Almaguer M, Garcés G, Saldaña-Arévalo M, Castellano P, Perez-Guardia E. 1993 Renal Transplantation Annual Data Report: Dialysis and Renal Transplantation Register of the Latin American Society of Nephrology and Hypertension. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schwedt E, Fernandez J, Gonzalez F, Mazzuchi N. Renal replacement therapy in Latin America during 1991-1995. Latin American Registry Committee. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:3083-3084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cusumano AM, Di Gioia C, Hermida O, Lavorato C. The Latin American Dialysis and Renal Transplantation Registry Annual Report 2002. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;68:S46-S52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cusumano AM, Romao JE, Poblete Badal H, Elgueta Miranda S, Gomez R, Cerdas Calderon M, Almaguer Lopez M, Moscoso J, Leiva Merino R, Sánchez Polo JV. [Latin-American Dialysis and Kidney Transplantation Registry: data on the treatment of end-stage renal disease in Latin America]. G Ital Nefrol. 2008;25:547-553. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Cusumano AM, Gonzalez Bedat MC, García-García G, Maury Fernandez S, Lugon JR, Poblete Badal H, Elgueta Miranda S, Gómez R, Cerdas Calderón M, Almaguer López M. Latin American Dialysis and Renal Transplant Registry: 2008 report (data 2006). Clin Nephrol. 2010;74 Suppl 1:S3-S8. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Cusumano AM, Garcia-Garcia G, Gonzalez-Bedat MC, Marinovich S, Lugon J, Poblete-Badal H, Elgueta S, Gomez R, Hernandez-Fonseca F, Almaguer M. Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry: 2008 prevalence and incidence of end-stage renal disease and correlation with socioeconomic indexes. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2013;3:153-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gonzalez-Bedat M, Rosa-Diez G, Pecoits-Filho R, Ferreiro A, García-García G, Cusumano A, Fernandez-Cean J, Noboa O, Douthat W. Burden of disease: prevalence and incidence of ESRD in Latin America. Clin Nephrol. 2015;83:3-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rosa-Diez G, Gonzalez-Bedat M, Pecoits-Filho R, Marinovich S, Fernandez S, Lugon J, Poblete-Badal H, Elgueta-Miranda S, Gomez R, Cerdas-Calderon M. Renal replacement therapy in Latin American end-stage renal disease. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | United States Renal Data System (USRDS). Annual Data Report United States Renal Data System 2015. [accessed. 2016;Jun 25] Available from: https://www.usrds.org/adr.aspx. |

| 26. | Kramer A, Pippias M, Stel VS, Bonthuis M, Abad Diez JM, Afentakis N, Alonso de la Torre R, Ambuhl P, Bikbov B, Bouzas Caamaño E. Renal replacement therapy in Europe: a summary of the 2013 ERA-EDTA Registry Annual Report with a focus on diabetes mellitus. Clin Kidney J. 2016;9:457-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pan American Health Organization. Strategic Plan of the Pan American Health Organization 2014-2019. Available from: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?gid=14004&option=com_docman&task=doc_view. |

| 28. | González-Bedat MC, Rosa-Diez GJ, Fernández-Cean JM, Ordúñez P, Ferreiro A, Douthat W. National kidney dialysis and transplant registries in Latin America: how to implement and improve them. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015;38:254-260. [PubMed] |