MAGNESIUM HOMEOSTASIS

Magnesium is the fourth most abundant intracellular ion, and despite its relatively low extracellular concentration, it has numerous essential functions in intracellular metabolism and ion transport. The majority of total body magnesium is housed within bone cells, while the remaining 1% circulates in the blood. As with most electrolytes, the balance of intake, absorption, and excretion in the gastrointestinal and renal systems, as well as the constant flux between the circulating and storage compartments within the serum and bone, respectively, are the determinants of magnesium homeostasis.

The small and large bowels are responsible for magnesium absorption via passive and active transport. Paracellular movement between intestinal epithelial cells, or enterocytes, occurs across a concentration gradient. Though the magnesium permeability of the small intestine is poorly understood, its relatively ion-permeable nature is presumed to be due to the relatively low expression of tight junction proteins[1]. Active transport of magnesium occurs more distally in the small intestine (i.e., cecum) and large bowel. The enterocyte apical cell membrane proteins transport magnesium from the intestinal lumen into the circulating blood via dedicated ion channels. Located on the luminal surface, these proteins have been identified as transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) 6 and 7. Their high affinity for magnesium actively helps the body maintain adequate magnesium levels through upregulation of magnesium absorption, especially in times of decreased magnesium intake[2-5]. The cyclin M4 exchanger (CNNM4 Na+-Mg+) is located on the basolateral surface and may be responsible for ultimate magnesium reabsorption into the serum after luminal absorption into the cytosol of the enterocyte[6]. During periods of decreased dietary magnesium, the active transport pathways can increase magnesium absorption significantly[7].

After absorption through the gastrointestinal tract, about 20% of magnesium in the blood is protein-bound (mostly to albumin), while 15% is complexed to anions. The remaining majority (65%) of extracellular magnesium is unbound in its ionized form. As opposed to other cations, like calcium, acid-base disturbances have little effect on this distribution[8]. Intracellularly, predominantly as the complexed, non-ionized form, magnesium has essential roles in the mechanisms behind the maintenance of DNA stability and repair as well as the regulation of the enzymatic activity of hundreds of enzymes[9]. Over the past two decades, numerous magnesium transporters have been identified, facilitating magnesium flux across cell membranes into the intracellular environment to accomplish these roles. The rate of transport varies among tissue types and higher concentrations of magnesium measured within rapidly growing cells suggests that the rate of intracellular magnesium transport is likely associated with the relative metabolic activity of the cell and its capacity to proliferate through its activating effect on DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis[10,11].

Approximately 80% of circulating magnesium is filtered into the urinary space. While most other ions are predominantly absorbed via the proximal tubule, the majority of filtered magnesium is reclaimed in the thick ascending Loop of Henle (TAL). In the TAL, the passive reabsorptive pathway is dependent on “claudins”, or tight junction proteins. Claudins 16 and 19, which are not expressed within the tight junctions of small intestine enterocytes, have been implicated as modulators of magnesium balance, and can lead to renal magnesium wasting when absent[12]. Additional studies show that claudins demonstrate “interdependence”, as they require each other for appropriate placement into the tight junctions within the distal convoluted tubule (DCT)[13]. Active, high affinity transcellular magnesium reclamation occurs through these TRPM6 transporters. As such, the DCT determines the ultimate magnesium concentration in the urine, and along with appropriate gastrointestinal absorption, ensures magnesium homeostasis.

In contrast to other predominantly intracellular cations such as potassium and calcium, and despite its crucial roles in cell proliferation and intracellular enzymatic activity, there is no hormonal axis solely dedicated to magnesium homeostasis. In addition, alterations in circulating serum magnesium concentrations are offset by a much larger intracellular magnesium depot, so that a negative daily magnesium balance may not manifest with lower magnesium concentrations. Intracellular magnesium depletion and normal serum magnesium concentrations may coexist, and total magnesium deficiency might not manifest until cellular stores are exhausted[9]. Therefore, using serum magnesium levels to diagnose magnesium deficiency is inherently challenging. The “intravenous magnesium loading test” is a method used to better approximate a magnesium deficit[14]. The concentrations of intravenously infused magnesium and the magnesium excreted in the urine are carefully measured to estimate total body magnesium balance. In individuals with sufficient total body magnesium, only 10% of the intravenously infused magnesium should be retained, while the remaining 90% is excreted through the urine. Individuals with intracellular magnesium depletion are expected to increase the absorption rate to > 50%-60%[15]. This test allows for a more accurate representation of the magnesium absorption required to achieve homeostasis. However, it is not performed in the context of patient care as a laboratory standard for accurate result interpretation does not yet exist. In the current state of the evaluation of magnesium disorders, despite the concerns noted above, clinicians and clinical researchers readily use serum magnesium concentrations to estimate total body magnesium.

EARLY REPORTS OF PROTON PUMP INHIBITOR INDUCED HYPOMAGNESEMIA

The link between proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use to hypomagnesemia was first recognized by the scientific community through a published case report in 2006[16]. Since then, numerous case reports have demonstrated this relationship, independent of other electrolyte abnormalities. These reports typically describe patients with chronic PPI exposure, presenting with symptoms characteristic of hypomagnesemia, including arrhythmias and symptoms of neuroexcitability such as seizures and tetany[17]. Numerous different formulations of PPIs have been implicated, indicating that the association is likely a drug class effect. Hypomagnesemia is typically improved after the PPI is discontinued, and PPI re-challenge results in hypomagnesemia recurrence[18]. Conversely, in patients prescribed histamine-2 receptor antagonists, an older class of medications for gastric acid suppression, hypomagnesemia does not recur. Notably, a majority of these case reports could not account for additional etiologies of magnesium deficiency, including malabsorptive conditions, poor dietary intake (i.e., malnutrition of alcohol use), or diuretic-related renal magnesium excretion, prompting the more recently published observational studies.

Estimating the exact usage of PPIs is difficult given its availability both over-the-counter and with a doctor’s prescription. It has been suggested that prescriptions for PPIs are in excess of 100 million per year. Increased reporting of the proton-pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia (PPIH) phenomenon to the United States Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Events Reporting System in combination with the early published case reports, resulted in the release of a “drug safety communication” in 2013[19]. The announcement alerted health care professionals to the risk of hypomagnesemia among chronic PPI users, particularly among those on a diuretic or other medications known to affect magnesium levels, with the consideration of obtaining baseline and regular follow-up serum magnesium concentrations over time. While large studies have confirmed this increased risk with concomitant diuretic use[20], others have encountered the PPIH phenomenon among both “casual” (intermittent) PPI users, and chronic users alike[21].

LIMITATIONS OF PUBLISHED OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES

Subsequent larger observational studies further support this association in both inpatient and outpatient populations[22-24], but all have significant limitations, and to date, no well-designed study to accurately describe the potential hypomagnesemic effect of PPIs has been done. While the FDA communication states that these effects occur in longer-term PPI use, duration of exposure to PPI therapy has been difficult to quantify in retrospective studies. PPIs are widely available without a prescription and this may lead to under-reporting to medical providers. Additionally, it is likely that some patients may be taking them on an “as-needed” basis rather than daily or twice a day, making any subsequent measurements of hypomagnesemia uninterpretable. Among the limitations of the observational data, residual confounding due to indication is perhaps the most challenging. Since PPIs are primarily used to treat disorders of the gastro-intestinal tract, and likely are also associated with alterations in dietary behavior, the PPI-associated hypomagnesemia could simply reflect less dietary intake. Furthermore, despite the widespread use of PPIs, the overall reported incidence of PPIH remains low. Although studies that examine the effect of PPI on either ionized magnesium concentrations, intracellular magnesium stores, or magnesium balance, have yet to be performed, a large observational study suggests the PPI exposure is not associated with an increased risk of arrhythmias, as one might expect in the setting of intracellular magnesium deficiency[25]. Uncertainty about the causal relationship of PPI use and magnesium will remain without carefully designed, prospective studies that clearly address PPI therapy duration and magnesium balance through the measurement of magnesium intake and magnesium excretion before and after PPI exposure.

THE PPIH PHENOMENON: POTENTIAL MECHANISMS

Early reports suggested that PPIH was not due to renal magnesium wasting, but rather decreased gastrointestinal absorption[26], and additional studies further support renal magnesium conservation in the setting of PPIH[27]. A recent study examining 24-h urine magnesium excretion in PPI-exposed patients showed that PPI users had lower urinary magnesium. The statistical models controlled for other measures of dietary intake, implicating decreased intestinal magnesium uptake[28]. These clinical observations highlighting decreased intestinal magnesium uptake are supported by more recent mechanistic studies, which have focused on the potential effect of PPI use on the TRMP6 transporter, the major pathway of intestinal magnesium absorption.

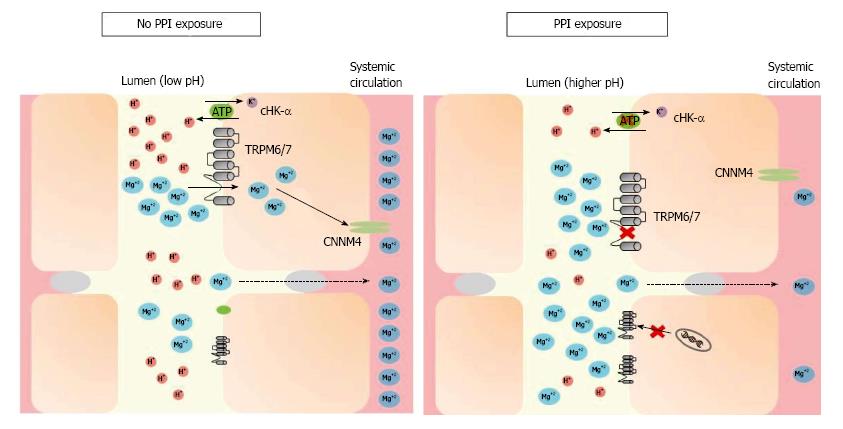

Intracellular magnesium regulates TRPM6 activity along with pH[29,30] whereby a more acidic milieu increases TRPM6 activity. Since PPI therapy decreases gastric hydrogen proton secretion, thereby increasing lumen pH, PPI use could potentially decrease TRPM6 activity, resulting in decreased magnesium absorption[31-33]. Figure 1 demonstrates this hypothesis. Adding complexity to this hypothesis, longer term PPI use actually increases the amount of intestinal protons in the distal small bowel[34] and significantly decreases basic pancreatic secretions[35]. However, since the majority of active magnesium reabsorption occurs in the cecum and colon, this effect may dissipate before reaching these locations further along the gastrointestinal tract.

Figure 1 Under conditions of magnesium deficiency, proton-pump inhibitors may inhibit magnesium absorption by increasing the pH of the intestinal lumen, through both gastric and non-gastric antagonism of the H+-K+ ATPase pump (“proton pump”).

TRPM6/7 affinity for magnesium decreases in a higher pH environment. While this may trigger mRNA transcription of TRPM6 channels in most individuals, hypomagnesemia may develop when this compensation is incomplete or the individual has additional risk factors. TRPM: Transient receptor potential melastatin; cHK-α: Colonic hydrogen-potassium ATPase; CNNM4: Cyclin M4; PPI: Proton-pump inhibitor.

PPI exposure may also lead to upregulation of the distal colon’s H+-K+ ATPase (cHK-α), a homolog of the gastric H+-K+ ATPase targeted by PPIs, increasing its activity by 30%[36]. However, when studied, increased cHK-α expression did not lead to any changes in serum magnesium levels, urinary magnesium excretion, or fecal magnesium excretion. Given this finding, it is plausible that this increased mRNA expression level of colonic TRPM6 may compensate for the reduced TRPM6 currents caused by the pH-dependent downregulation described above[31]. While this appropriate overexpression of TRPM6 in times of magnesium deficiency may help ameliorate intestinal magnesium malabsorption and maintain total body magnesium balance, individual epigenetic variations in this response could explain why PPI-induced hypomagnesemia is not uniformly seen among PPI users[37,38].

While never evaluated in the setting of PPI use, early studies have employed a radiolabeled magnesium challenge and suggest that the magnesium secretion from the intestine is a small component of magnesium homeostasis[39]. It is currently unclear whether the lack of a “sensing mechanism” within enterocytes that could prompt upregulation of magnesium absorption in times of dietary magnesium restriction could contribute to the clinically significant hypomagnesemia seen in some with PPIH.

Although most have focused on a potential effect of PPI therapy on the TRPM6, and potentially, the Cyclin M4 (CNNM4), transporters in the intestine, there are a number of other ubiquitously expressed transporters previously identified as contributory to magnesium homeostasis including TRPM7[4], magnesium transporter 1 (MagT1)[40], Cyclin M3 (CNNM3)[41], solute carrier family 41 member 1 (SLC41A1)[42], nonimprinted in Prader-Willi/Angelman Syndrome family (NIPA)[43], and membrane magnesium transporters 1 and 2 (MMgT1/2)[44]. While these transporters may play important roles in overall magnesium homeostasis, their role in magnesium transport and specific locations within the colon is unclear. Therefore, they remain potential targets for investigation of how PPIs may interact with them and ultimately lead to hypomagnesemia.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have also identified potential loci that may influence serum magnesium levels[45]. Follow-up studies in individuals of African-American ancestry specifically focused on two loci, MUC1 and the aforementioned TRPM6, and analyzed gene-environment interactions, finding significant effect modification of insulin levels with TRPM6 and progestin levels with MUC1[46]. While the mechanism of TRPM6-associated hypomagnesemia is better characterized, the influence of transcriptional variations of MUC1, which normally encodes a transmembrane mucin forming part of the mucosal barrier of the intestine[47], remains unexplored.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Nearly a decade after the initial reporting of PPIH, there is increasing awareness of the phenomenon. Case reports and observational studies have contributed to our understanding of the prevalence of PPIH among a variety of patient populations with unique risk factors for its development. In conjunction with the clinical findings of preserved renal magnesium reabsorption in periods of magnesium deficiency, molecular physiology studies have proposed a viable pH-dependent mechanism for the role of TRPM6 within colonic enterocytes. However, much uncertainty regarding the relatively rare occurrence of PPIH remains, with individual genetic variation at specific loci and under-characterized magnesium transporters among the highest-yield unexplored research directions. Additionally, prospective studies that carefully control for nutritional intake among PPI users and accurately measure total body magnesium are needed to help determine causality of the association of PPI use and hypomagnesemia.

P- Reviewer: Kelesidis T, Thompson JR S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ