Revised: April 23, 2013

Accepted: May 1, 2013

Published online: May 6, 2013

Processing time: 103 Days and 0.8 Hours

An 86-year-old man, diagnosed as having mycosis fungoides in May 2008 and treated with repeated radiation therapy, was admitted to our hospital for initiation of hemodialysis due to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in April 2012. On admission, his corrected serum calcium level was 9.3 mg/dL, and his intact parathyroid hormone level was 121.9 pg/mL (normal range 13.9-78.5 pg/mL), indicating secondary hyperparathyroidism due to ESRD. After starting hemodialysis, urinary volume diminished rapidly. The serum calcium level increased (12.7 mg/dL), and the intact parathyroid hormone level was suppressed (< 5 pg/mL), while the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol) level increased (114 pg/mL, normal range: 20.0-60.0 pg/mL) in June 2012. The possibilities of sarcoidosis and tuberculosis were ruled out. Skin biopsies from tumorous lesions revealed a diagnosis of granulomatous mycosis fungoides. The serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels and the degrees of skin lesions went in parallel with the increased serum calcium and calcitriol levels. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed as having calcitriol-induced hypercalcemia possibly associated with granulomatous mycosis fungoides. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides is rare, and its association with calcitriol-induced hypercalcemia has not been reported. Careful attention to calcium metabolism is needed in patients with granulomatous mycosis fungoides, especially in patients with ESRD.

Core tip: Granulomatous mycosis fungoides is a rare subtype with granuloma formation in mycosis fungoides. In addition, the incidence of calcitriol-induced hypercalcemia by granulomatous mycosis fungoides has not been reported until now. Much attention should be paid to calcium metabolism in patients of granulomatous mycosis fungoides, especially in patients complicated with end-stage renal disease, because urinary calcium excretion decreases for end-stage renal disease.

- Citation: Iwakura T, Ohashi N, Tsuji N, Naito Y, Isobe S, Ono M, Fujikura T, Tsuji T, Sakao Y, Yasuda H, Kato A, Fujiyama T, Tokura Y, Fujigaki Y. Calcitriol-induced hypercalcemia in a patient with granulomatous mycosis fungoides and end-stage renal disease. World J Nephrol 2013; 2(2): 44-48

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v2/i2/44.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v2.i2.44

Mycosis fungoides is a rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, classified as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma[1,2]. Although hypercalcemia is relatively rare (approximately 1.0%)[3], it is caused by non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and one-third of the causes for hypercalcemia is associated with increased production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol)[4]. In general, mycosis fungoides does not cause hypercalcemia[5]. There are various subtypes and variants in mycosis fungoides, and granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin disease are rare subtypes with granuloma formation[1,6]. To the best of our knowledge, only one case of hypercalcemia induced by elevated calcitriol has been reported in granulomatous slack skin disease[7], but there have been no reports of hypercalcemia associated with granulomatous mycosis fungoides. A patient with calcitriol-induced hypercalcemia possibly in association with granulomatous mycosis fungoides and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is reported.

An 86-year-old man was admitted to our hospital to start hemodialysis due to ESRD and treatment for cellulitis of the left forearm in April 2012. He was diagnosed as having stage II mycosis fungoides by dermatologists in our hospital in May 2008. Although there were typical histopathological features of mycosis fungoides, including an infiltrate of atypical medium-sized CD4+ T cells with epidermotropism, no histiocytic infiltrate or granuloma formation was found at that time. The skin lesions were repeatedly treated with topical corticosteroid therapy and narrow-band ultraviolet B irradiation. In November 2008, his serum creatinine (Cr) was 1.17 mg/dL, and his urinalysis showed positive urinary protein (3.3 g/d) with hematuria. A renal biopsy could not be performed, because abdominal computed tomography revealed that both kidneys were already atrophic. His renal function deteriorated gradually, and he complained of general fatigue and exertional dyspnea due to uremia in April 2012. Mycosis fungoides progressed to stage III, and he developed cutaneous tumors on his head, neck, and hip despite repeated irradiation.

Physical examination on admission showed a height of 164.3 cm, weight of 71.8 kg (weight gain of 8 kg over one month), blood pressure of 138/62 mmHg, a regular pulse rate of 62 beats/min, and a percutaneous oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 90% on room air. The palpebral conjunctiva appeared slightly anemic, and the jugular vein was dilated. The heart sounds were distinct with no audible murmurs. Coarse crackles were prominent in both lungs. The left forearm was reddened and swollen due to cellulitis. Pitting edema was present in both lower limbs. Patches and infiltrated plaques with scale were found on his skin over the entire body. Dome-shaped tumors, 3-5 cm in diameter, were also found, especially on his head, neck, and buttocks. Hanging skin folds, which are occasionally seen in granulomatous slack skin disease, were not present. There was no palpable cervical, axillary, or femoral lymphadenopathy. The results of a peripheral blood cell analysis were as follows: white blood cell count 5510/μL, hemoglobin 5.4 g/dL, and platelet count 28.0 × 104/μL. Blood chemistry results were as follows: blood urea nitrogen 84.8 mg/dL, Cr 6.15 mg/dL, total protein 6.3 g/dL, serum albumin 2.4 g/dL, potassium 4.8 mEq/L, calcium 9.3 mg/dL (normal range, 8.7-11.0 mg/dL), inorganic phosphate 5.8 mg/dL, intact-parathyroid hormone (i-PTH) 121.9 pg/mL (normal range, 13.9-78.5 pg/mL), C-reactive protein 3.87 mg/dL, ferritin 199 ng/mL, IgG 1630 mg/dL, IgA 556 mg/dL, IgM 16 mg/dL, and soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) 4250 IU/mL (normal range, 145-519 IU/mL). Arterial blood gas analysis showed pH 7.370, partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) 48 mmHg, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) 35 mmHg, HCO3- 19.7 mmol/L, and an anion gap 11.0 mmol/L. Urinalysis showed proteinuria of 2.8 g/day with hematuria, fractional excretion of calcium 3.3% (normal range, 1%-2%), and creatinine clearance of 7.7 mL/min. A chest X-ray showed bilateral pleural effusions, and the cardiothoracic ratio was 65%.

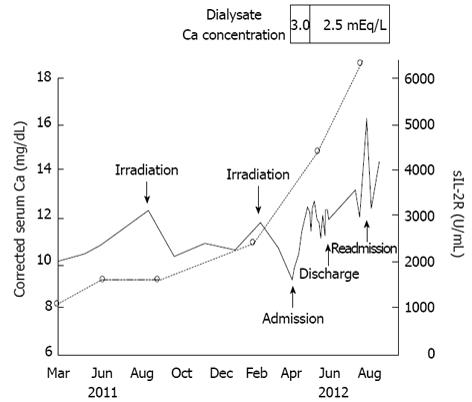

Hemodialysis was started after admission, and his general condition improved to good in a few days. Although cellulitis recurred and developed to bacteremia, it was also cured by adequate intravenous antibiotic therapy. However, the skin lesions of mycosis fungoides deteriorated progressively. The patient’s clinical course is shown in Figure 1. His corrected serum calcium levels were 8.8-10.1 mg/dL up to May 2011 (data not shown). Hypercalcemia was found in July 2011 (corrected serum calcium: 11.5 mg/dL). However, serum calcium levels decreased with irradiation therapy in parallel with suppression of disease activity of mycosis fungoides. After hemodialysis was started, urinary volume decreased rapidly, and the serum calcium levels increased without administration of vitamin D3 or calcium products. On day 20, the serum calcitriol level was 114 pg/mL, the parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) level was less than 1.0 pmol/L, and the i-PTH level decreased to less than 5 pg/mL. Therefore, his hypercalcemia was considered to be due to overproduction of calcitriol.

The cause of calcitriol overproduction was investigated. Interferon gamma release assays were negative, and angiotensin converting enzyme was 10.7 IU/L (normal range, 8.3-21.4 IU/L). Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy was not seen on chest X-ray. Thoracoabdominal computed tomography did not show any lymphadenopathy or abnormal masses. Ophthalmological examination did not reveal uveitis. Taken together, tuberculosis and sarcoidosis were excluded. Gallium scintigraphy demonstrated mild accumulations in the head, neck, and buttocks, confined to the tumor regions of mycosis fungoides.

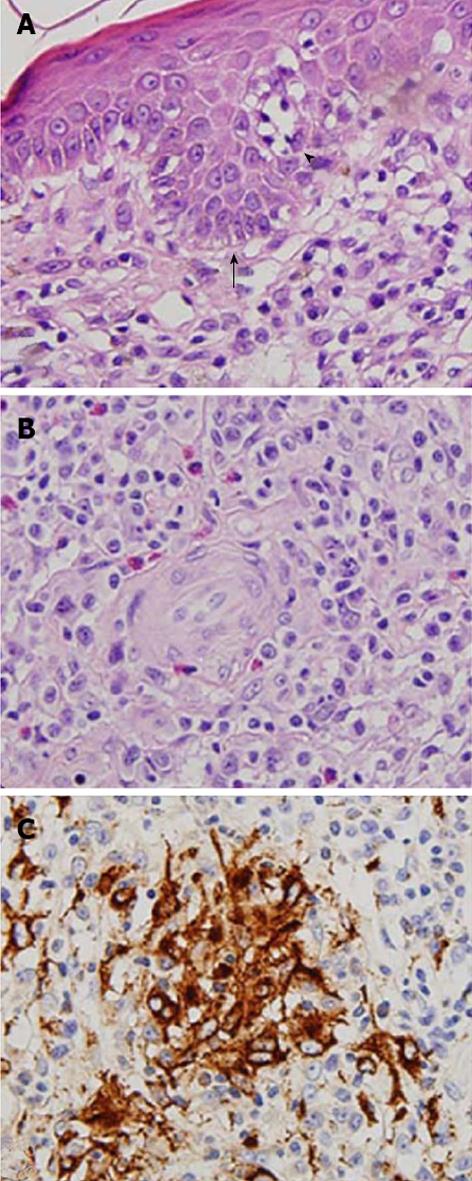

To address the possible mechanism underlying the granuloma formation related to hypercalcemia, skin biopsies were performed from tumor regions of mycosis fungoides on his neck, abdomen, and waist. Histological examination revealed clusters of atypical lymphocytes forming Pautrier microabscesses within the epidermis and diffuse and dense, small to medium-sized atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic and convoluted nuclei throughout the whole dermis. Epidermotropism of lymphocytes was found (Figure 2A). Granuloma formation with aggregation of histiocytes was found, and multinucleated histiocytic giant cells were present (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemistry showed that the majority of the atypical lymphocytes was positive for CD4 and negative for CD7. In addition to foreign body granuloma around invaded hair follicles, granulomatous infiltration consisting of CD68+ epithelioid histiocytes was observed in the deep dermis (Figure 2C). These features were compatible with granulomatous mycosis fungoides.

The patient was not given oral corticosteroid therapy for the hypercalcemia, because he presented with repeated cellulitis and bacteremia during hospitalization, and he was considered a compromised host due to mycosis fungoides and ESRD. His serum calcium levels increased gradually and reached 12.7 mg/dL on day 30. However, change of the dialysate calcium concentration from 3.0 to 2.5 mEq/L decreased serum calcium levels to around 11 mg/dL (Figure 1). The patient was discharged from our hospital in June 2012 after being given guidance regarding avoidance of exposure to sunlight and excessive calcium intake. Continued irradiation therapy was determined by dermatologists in our hospital, because his clinical course showed that irradiation therapy was effective to control his serum calcium levels (Figure 1). Two months later, he was readmitted to our hospital for irradiation therapy. His serum calcium level (16.3 mg/dL) and calcitriol level (129 pg/mL) increased further. Unfortunately, he deteriorated to a vegetative state due to an acute subdural hematoma caused by a bruise to the head on day 3 after the second hospitalization. The patient was transferred to another hospital in September 2012.

Mycosis fungoides is a rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, classified as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma[1,2]. The estimated annual incidence rates of mycosis fungoides are approximately 0.36 and 0.64 per 100000 in Europe and the United States, respectively[8,9]. Although it is rare, non-Hodgkin lymphoma causes hypercalcemia (approximately 1.0%)[3]. One-third of these cases is associated with overproduction of calcitriol[4], and the origin of the elevated serum calcitriol in these cases is uncontrolled endogenous production of calcitriol, through 1α-hydroxylase, by malignant lymphocytes[10] and macrophages[11], or both.

Mycosis fungoides is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but hypercalcemia occurring in patients with mycosis fungoides has not been reported[5]. There are some subtypes of mycosis fungoides, and granulomatous mycosis fungoides is a rare one that has distinct histological features[6]. Granulomatous formation with aggregations of histiocytes accompanied by epidermotropism of lymphocytes is found in granulomatous mycosis fungoides[12]. Granulomatous formation is divided into several patterns, and sarcoid-like granuloma is the most common pattern[13]. However, there have been no reports of hypercalcemia induced by granulomatous mycosis fungoides. In the present case, CD68+ macrophage infiltration and epithelioid granuloma formation were found in the skin biopsy specimens obtained from several parts. In addition, the serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels and the degrees of skin lesions went in parallel with the increased serum calcium and calcitriol levels. The above-mentioned facts suggest that hypercalcemia might be derived from elevated calcitriol levels induced by granulomatous mycosis fungoides in this patient.

Several facts provide evidence for the association between hypercalcemia and mycosis fungoides in this case. First, it has been reported that the incidence of hypercalcemia in non-Hodgkin lymphoma correlates with histological grade, and the incidence of hypercalcemia is only 1%-2% in the low-grade group, whereas it is as high as 30% in the high- and intermediate-grade groups[14,15]. The elevation of serum calcium levels correlates with the histological grade and the degree of host macrophage infiltration into lymphomatous tissue[4]. Goteri et al[16] reviewed cases of biopsy-proven mycosis fungoides and classified their histological features into 4 grades based on the quantity and distribution of infiltrating cells. According to the classification, in the present case, the highest grade was present and may have been correlated with hypercalcemia. Next, after hemodialysis was started, hypercalcemia became marked with decreased urinary volume. Hypercalcemia is not evident as long as renal function is intact, because calcium can be excreted into the urine. In fact, it is reported that 17% of patients who presented with non-Hodgkin lymphoma had hypercalciuria, even though no patients showed overt hypercalcemia[17]. They indicate that it is possible that renal function deterioration to ESRD contributed to hypercalcemia in the present case.

A case of calcitriol-induced hypercalcemia in a patient with granulomatous mycosis fungoides with ESRD was described. Although the incidence of hypercalciuria, hypercalcemia, and hypervitaminosis D3 in mycosis fungoides has not been fully elucidated, careful attention should be paid to calcium metabolism in patients with mycosis fungoides, especially granulomatous mycosis fungoides with ESRD.

The authors would like to thank all of the staff at the Department of Dermatology in Hamamatsu University School of Medicine for their cooperation in diagnosing the patient with granulomatous mycosis fungoides.

P- Reviewers Scarpioni R, Nemcsik J S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, Swerdlow SH, Ralfkiaer E, Chimenti S, Diaz-Perez JL, Duncan LM. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2714] [Cited by in RCA: 2576] [Article Influence: 128.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, Willemze R, Kim Y, Knobler R, Zackheim H, Duvic M, Estrach T, Lamberg S. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:1713-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 976] [Cited by in RCA: 996] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Newman BM, Taylor SH, Guinee VF. Incidence of hypercalcemia in patients with malignancy referred to a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 1993;71:1309-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seymour JF, Gagel RF. Calcitriol: the major humoral mediator of hypercalcemia in Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Blood. 1993;82:1383-1394. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Dodd RC, Winkler CF, Williams ME, Bunn PA, Gray TK. Calcitriol levels in hypercalcemic patients with adult T-cell lymphoma. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:1971-1972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Siriphukpong S, Pattanaprichakul P, Sitthinamsuwan P, Karoopongse E. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with large cell transformation misdiagnosed as leprosy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93:1321-1326. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Karakelides H, Geller JL, Schroeter AL, Chen H, Behn PS, Adams JS, Hewison M, Wermers RA. Vitamin D-mediated hypercalcemia in slack skin disease: evidence for involvement of extrarenal 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1alpha-hydroxylase. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1496-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Morales-Suárez-Varela MM, Olsen J, Johansen P, Kaerlev L, Guénel P, Arveux P, Wingren G, Hardell L, Ahrens W, Stang A. Occupational risk factors for mycosis fungoides: a European multicenter case-control study. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:205-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:854-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ghazi AA, Attarian H, Attarian S, Abasahl A, Daryani E, Farasat E, Pourafkari M, Tirgari F, Ghazi SM, Kovacs K. Hypercalcemia and huge splenomegaly presenting in an elderly patient with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;19:330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hewison M, Kantorovich V, Liker HR, Van Herle AJ, Cohan P, Zehnder D, Adams JS. Vitamin D-mediated hypercalcemia in lymphoma: evidence for hormone production by tumor-adjacent macrophages. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:579-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | LeBoit PE, Zackheim HS, White CR Jr. Granulomatous variants of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The histopathology of granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:83-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, Lucioni M, Wechsler J, Audring H, Assaf C, Rüdiger T, Willemze R, Meijer CJ. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization For Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Burt ME, Brennan MF. Incidence of hypercalcemia and malignant neoplasm. Arch Surg. 1980;115:704-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Baechler R, Sauter C, Honegger HP, Oelz O. [Hypercalcemia in non-Hodgkin lymphoma]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1985;115:332-334. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Goteri G, Filosa A, Mannello B, Stramazzotti D, Rupoli S, Leoni P, Fabris G. Density of neoplastic lymphoid infiltrate, CD8+ T cells, and CD1a+ dendritic cells in mycosis fungoides. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:453-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |