Published online Jun 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i2.100530

Revised: February 3, 2025

Accepted: March 4, 2025

Published online: June 25, 2025

Processing time: 233 Days and 9.8 Hours

Malakoplakia is a rare chronic granulomatous disease associated with gram-negative infection, predominantly by Escherichia coli. It is induced by defective phagolysosomal activity of the macrophages. Malakoplakia commonly affects the urinary bladder but has been shown to affect any solid organ, including the native and transplanted kidney. However, isolated malakoplakia of the kidney allograft is rare. Transplant recipients with compromised immune systems are more likely to develop malakoplakia.

We report three cases of kidney allograft parenchymal malakoplakia in kidney transplant recipients on immunosuppression that were successfully managed with good outcomes. We described the clinical characteristics of all the kidney allograft malakoplakia cases documented in the literature. A total of 55 cases of malakoplakia were reported in recipients with a history of kidney transplant. A total of 27 recipients had malakoplakia involving the allograft, and others had malakoplakia in other organs. The common presentations included allograft dysfunction, pyelonephritis, and allograft or systemic mass. Most recipients had favorable outcomes with appropriate management that included prolonged antibiotic therapy and adjustment of immuno

This case series provides an overview of the etiology, presentation, pathogenesis, and management of malakoplakia in kidney transplant recipients.

Core Tip: Patients with an immunosuppressed state, such as renal transplantation, are at increased risk of developing malakoplakia. This disease has varied presentations and is challenging to diagnose. We present our recent experience in the diagnosis and management of malakoplakia in renal transplant recipients. We were able to review the documented cases of malakoplakia among renal transplant recipients in the literature and summarize our findings. We made conclusions concerning its presentation, association with transplant rejection, and management strategies.

- Citation: Simhadri PK, Contractor R, Chandramohan D, McGee M, Nangia U, Atari M, Bushra S, Kapoor S, Velagapudi RK, Vaitla PK. Malakoplakia in kidney transplant recipients: Three case reports. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(2): 100530

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i2/100530.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i2.100530

Malakoplakia is a rare chronic granulomatous disease associated with gram-negative infection, predominantly by Escherichia coli (E. coli). It is induced by defective phagolysosomal activity of the macrophages. Malakoplakia commonly affects the urinary bladder but has been shown to affect any solid organ, including the native and transplanted kidney. However, isolated malakoplakia of the kidney allograft is rare.

Transplant recipients are more likely to develop malakoplakia due to compromised immune systems. We report three kidney allograft parenchymal malakoplakia cases and describe the pathological lesions of malakoplakia, particularly the pathognomonic Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, and their clinical course. We reviewed the clinical characteristics of all the post-kidney-transplant malakoplakia cases documented in the literature. We summarized recently published reports about the disease's pathogenesis, morphology, and clinical course.

Case 1: A 66-year-old African American (AA) male received a deceased donor kidney transplant (DDKT). The post-transplant course was complicated with E. coli transplant pyelonephritis, low-grade cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia, and later recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI) within the first six months post-transplant. He was on extended-release tacrolimus (Envarsus) 20 mg daily with a target concentration of 6-8 ng/mL, Mycophenolate Sodium (Myfortic) 360 mg twice daily (due to CMV viremia), and prednisone 5 mg daily.

Six months post-transplant, he developed worsening allograft function, with creatinine concentration elevation to 2.74 mg/dL from a baseline of 1.7 mg/dL. His workup showed asymptomatic E. coli bacteriuria, for which he was prescribed a two-week course of oral cefpodoxime 500 mg daily.

Case 2: A 39-year-old AA female's post-transplant course was complicated by disseminated Nocardia with pulmonary and neurological lesions and ocular involvement eight months post-transplant. She completed a 12-month course of Bactrim + moxifloxacin and was noted to have residual lesions in the lungs and brain. Follow-up imaging was performed to ensure the resolution of Nocardia lesions.

Case 3: One-month post-transplant, a 62-year-old White male presented with nausea, vomiting, decreased urine output, and chills. He was on the following immunosuppressive regimen: (1) Tacrolimus 3 mg twice daily; (2) Prednisone 5 mg daily; and (3) Myfortic 500 mg twice daily.

Case 1: He with a past medical history of kidney cell carcinoma, a history of prostate cancer, end stage kidney disease (ESKD) due to hypertensive nephrosclerosis.

Case 2: Her with a history of ESKD secondary to type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and arterial hypertension (HTN) had a simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation.

Case 3: He with a past medical history of ESKD secondary to diabetic nephropathy and HTN had deceased donor kidney transplantation.

Case 1: He denied any symptoms during his follow-up in the transplant clinic. Vital signs showed a temperature of 97.3 F, blood pressure of 143 mmHg/82 mmHg, heart rate of 75/minute, and a respiratory rate of 16/minute. Physical examination demonstrated normal cardio-pulmonary findings and no allograft tenderness or peripheral edema.

Case 2: Physical examination demonstrated normal cardio-pulmonary findings. She was noted to have allograft tenderness.

Case 3: On examination, he was febrile at 101F and had dry mucus membranes and right lower quadrant abdominal transplant tenderness.

Case 1: Urine studies demonstrated > 100 white blood cells/high power field and > 100 red blood cells/high power field. Creatinine elevation to 2.74 mg/dL from a baseline of 1.7 mg /dL. Laboratory results are detailed in Table 1.

| Laboratory | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Normal range |

| White blood cell | 5100 | 11.7 | 5.7 | 4000-11000/mm3 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.4 | 10.7 | 8.8 | 12-16 gr/dL |

| Platelet count | 217000 | 391000 | 65000 | 150000-450000/mm3 |

| Na | 138 | 135 | 127 | 136-145 mmol/L |

| K | 5.4 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 3.5-5 mmol/L |

| Cl | 106 | 100 | 96 | 96-106 mmol/L |

| HCO3- | 24 | 17 | 21 | 22-26 mmol/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 31.4 | 24.5 | 33 | 6-24 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 2.74 | 1.82 | 2.75 | 0.7-1.1 mg/dL |

Case 2: Laboratory evaluation showed an elevation of creatinine to 1.8 mg/dL; the other results are detailed in Table 1. Urine cultures revealed E. coli, and she started on IV cefepime and then switched to cefpodoxime on discharge for two weeks with plans for an outpatient allograft kidney biopsy after completion of antibiotics.

Case 3: His initial workup revealed acute kidney injury with an elevated serum creatinine concentration of 2.75 mg/dL (baseline 1.5-1.8 mg/dL); urinalysis showed pyuria and nitrites. Donor-specific antibodies were negative. Urinalysis revealed a white blood cell of 40/hpf, a red blood cell of 17/hpf, and a positive urine culture for E. coli. Other pertinent results at admission are shown in Table 1. He was followed up in the transplant clinic two weeks later and had an ele

Case 1: The allograft ultrasound (US) demonstrated a 2.4 cm nodular area in the inferior pole of the kidney transplant. He subsequently underwent an initial kidney biopsy, which was positive for acute tubular injury but negative for rejection and minimal interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen was per

Case 2: Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed findings consistent with acute pyelonephritis of the right lower quadrant of the kidney transplant with mild transplant hydronephrosis. A transplant kidney US showed a 3.2 cm hypoechoic mass-like area in the lower pole of the kidney transplant with hydronephrosis.

Case 3: A kidney transplant US showed a minimally complex 6.0 cm peri-transplant collection, which required placement of a drain, and the workup was consistent with a urinoma.

He underwent a biopsy of the kidney mass, which demonstrated malakoplakia. Urine cultures were again positive for E. coli.

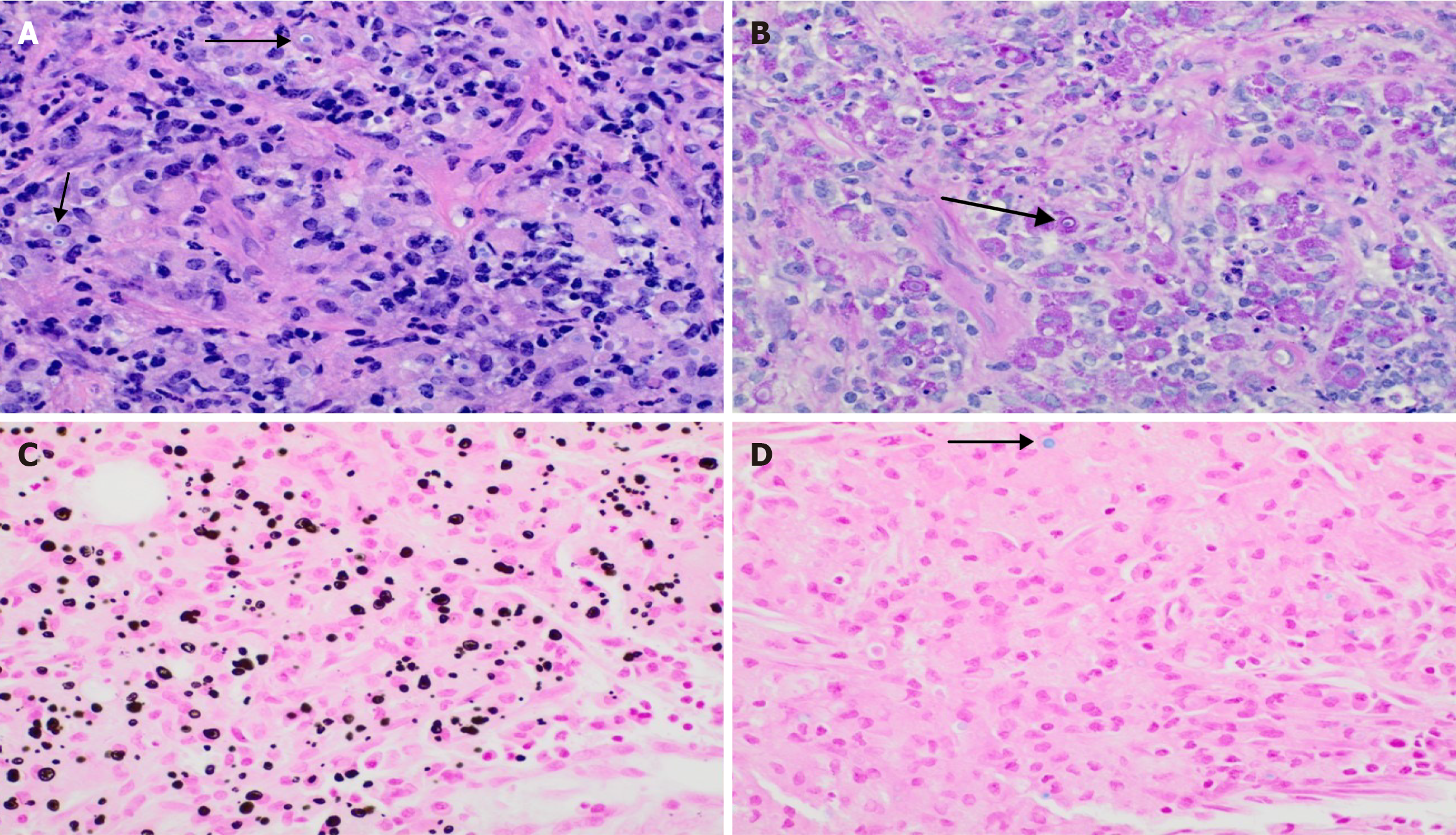

She had a biopsy from the allograft kidney a month later due to worsening kidney function, which showed Banff type IA grade acute cellular rejection and malakoplakia. For case 2, histological examination showed segmental sclerosed and extensive about 70% interstitial fibrosis with proportional tubular atrophy, findings diagnostic of acute T-cell mediated rejection, grade 1A with moderate-to-severe interstitial inflammatory cells with abundant plasma cells and lymphocytes. In addition, there were focal interstitial neutrophils in addition to the plasma cells that showed rimming around tubules, neutrophilic tubulitis, and focal neutrophilic casts. These findings in this recipient with a recent history of E. coli urinary tract infection are diagnostic of focal acute pyelonephritis. Moreover, there were focal sheets of macrophages adjacent to the area with acute pyelonephritis that have abundant PAS-positive granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Von Hansemann cells) and basophilic inclusions that show focal targetoid appearance characteristic of Michaelis-Gutmann bodies and stained positive for calcium and iron, findings diagnostic of malakoplakia.

The allograft biopsy was negative for rejection but showed malakoplakia.

For cases 1 and 3, histological examination from the transplant biopsy showed chronic inflammatory sheets of macro

He was started on intravenous (IV) cefepime for a week and then discharged on oral Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) and the repeat imaging showed persistent biopsy-proven kidney malakoplakia three months later. He was given IV Cefepime for a week and continued on oral cefuroxime therapy for six months.

Rejection was treated with IV thymoglobulin. Repeat urine cultures grew Acinetobacter. She was treated with IV ceftriaxone for pyelonephritis and was discharged to continue with oral TMP/SMX DS until the resolution of imaging findings.

He was given cefuroxime for 6 months.

A repeat MRI later showed decreased size in the kidney lesions, and serum creatinine concentration reached a nadir of 1.2 mg/dL.

A follow-up MRI three months later showed complete resolution in malakoplakia and complete resolution of hydrone

A repeat kidney imaging three months later demonstrated a resolution of malakoplakia.

Malakoplakia is a rare chronic granulomatous infectious disease involving the skin and other organs[1,2]. Malakoplakia was first described by von Hansemann in 1901 and 1902 by Michaelis and Gutmann[3]. It is most frequently reported to occur in the genitourinary system. The first case of malakoplakia reported outside the genitourinary system was in 1958[4]. Malakoplakia is believed to result from the inadequate killing of bacteria by macrophages or monocytes that exhibit defective phagolysosomal activity[5]. Reduced monocytic cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels and decreased release of ß-glucuronidase lead to impaired lysosomal clearance, leading to bacterial residues in macrophages. Partially digested bacteria accumulate in monocytes or macrophages and lead to the deposition of calcium and iron on residual bacterial glycolipids. The presence of the resulting basophilic inclusion structure, the Michaelis-Gutmann body, is considered pathognomonic for malakoplakia[5-7]. These macrophages with pathological Michaelis-Gutmann bodies are called Von Hansemann cells.

The most common organism isolated was E. coli. Other organisms isolated include Klebsiella and Proteus species. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Rhodococcus equi are rarely encountered in recipients with malakoplakia[8].

An immunodeficient state favors the increased incidence of malakoplakia in immunocompromised states, including post-organ transplantation, DM, chronic alcohol intake, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, malignancy, and immunosuppressive therapy, which suggests that an impaired function of T lymphocytes may play a role in the pathogenesis of malakoplakia[3,6,7]. Partial or complete resolution of phagocytic cell dysfunction has been shown to occur in recipients with malakoplakia after cessation of immunosuppressive therapy[2,6-9].

We report these cases because of the rarity of isolated malakoplakia on kidney allografts and the scarcity of medical literature regarding management. Immunosuppression predisposes and increases kidney transplant recipients to gram-negative bacterial infections and subsequently to the development of malakoplakia. The differential diagnosis of malakoplakia includes other chronic inflammatory processes such as mycobacterium avium infections and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis.

In all of our cases, malakoplakia was diagnosed by biopsy, and two showed resolution of malakoplakia with TMP/SMX DS confirmed by serial imaging modalities. The other case demonstrates the complexity of managing and the need for therapy adjustments to achieve curative treatment.

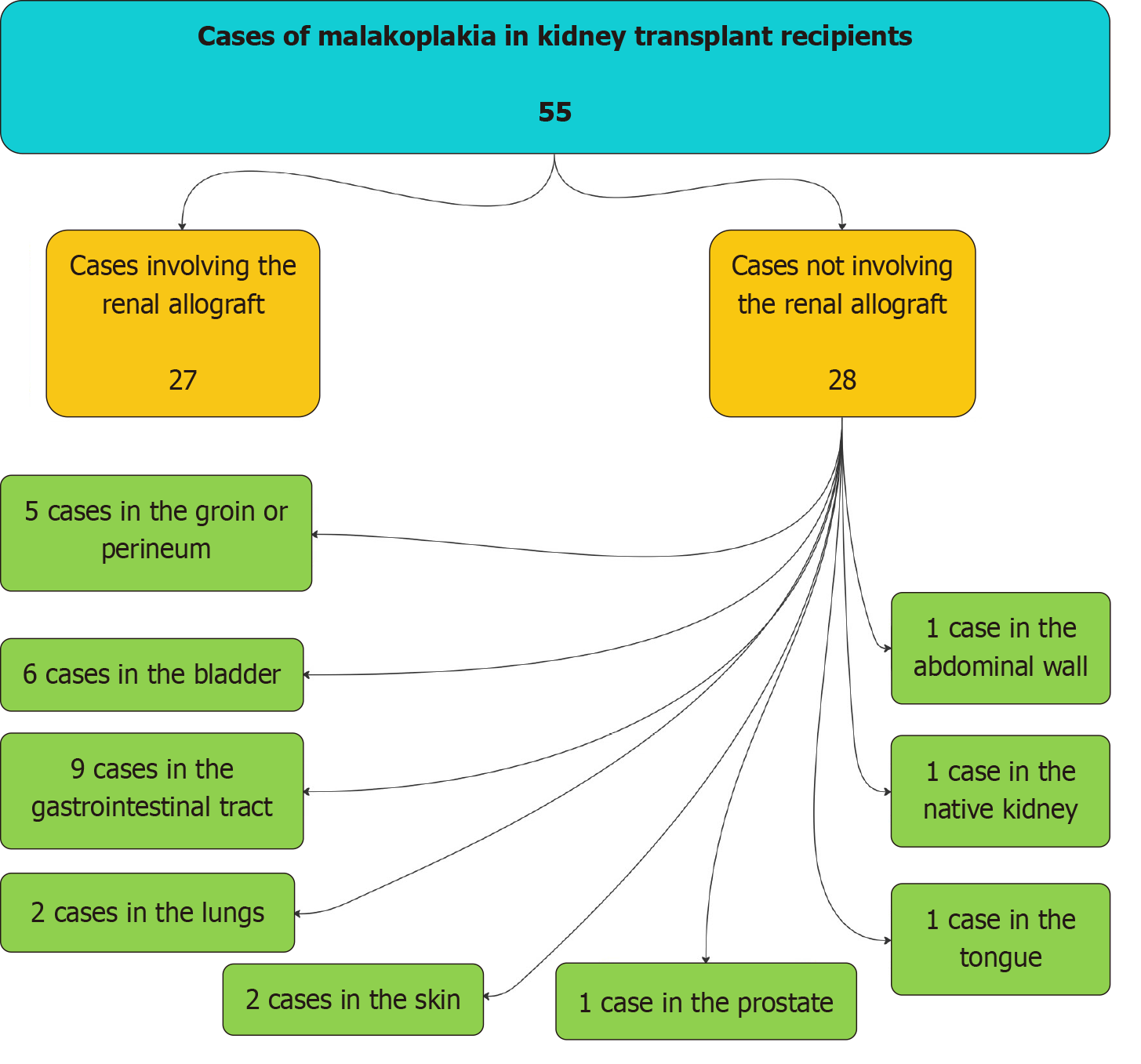

We reviewed the literature in PubMed for cases of malakoplakia among kidney transplant recipients. Publications not in English were excluded, and we identified 55 cases (Figure 2) published among kidney transplant recipients (including the current 3 cases). Of the 55 reported cases, 27 involved the kidney allograft (Table 2)[7,10-30], and 28 involved other internal organs instead of the kidney allograft (Table 3)[6,9,31-54]. Out of these 28 cases of Malakoplakia involving other organs, nine involved the gastrointestinal tract, 6 involved the bladder, 5 involved the groin or perineum, 2 involved the lung, 2 involved the skin, 1 involved the prostate, 1 involved the abdominal wall, 1 involved the tongue, and 1 involved the native kidney (Table 3)[6,9,31-54].

| Ref. | Age (years) | Sex | Native disease | Time after transplant | Prior rejection | Organism | Antibiotic duration | Outcome |

| Case 1 | 66 | M | HTN | 8 months | No | E. coli | 8 months | Improved |

| Case 2 | 39 | F | HTN, DM | 33 months | Yes | E. coli | 3 months | Improved |

| Case 3 | 62 | M | HTN, DM | 1 month | No | E. coli | 6 months | Improved |

| Vishwajeet et al[10], 2023 | 49 | F | NR | 12 years | Yes | E. coli | NR | Improved |

| Rustom et al[11], 2023 | 55 | M | HTN | 5 months | NR | E. coli | Long-term | Improved |

| Triozzi et al[12], 2022 | 40 | F | Hemolytic uremic syndrome | 4 months | No | E. coli | 30 days | Improved |

| Yim et el[7], 2022 | 33 | F | GN | 6 months | Yes | E. coli | 22 days | Improved |

| Park et al[13], 2020 | 59 | F | DKD | 6 months | NR | NR | Long-term | Improved |

| Lee et al[14], 2022 | 59 | F | NR | 18 months | Yes | E. coli | NR | Improved |

| Patel et al[15], 2021 | 45 | F | GN | 16 months | Yes | E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae | Long-term | Improved |

| Kalimuthu et al[16], 2021 | 41 | F | NR | 1 year | NR | Culture negative | NR | NR |

| Kinsella et al[17], 2021 | 63 | F | NR | 7 months | NR | E. coli | 3 months | Improved |

| Kinsella et al[17], 2021 | 52 | F | NR | 4 months | NR | E. coli | 6 months | Improved |

| Tan et al[18], 2021 | 55 | F | Lithium | NR | NR | E. coli | 4 months | NR |

| Khojah[19], 2020 | 74 | F | NR | 2 years | No | E. coli, Enterobacter aerogenes | Long-term | Improved |

| Khojah[19], 2020 | 62 | F | NR | 6 years | No | Culture-negative | 6 months | Improved |

| Yasin et al[20], 2018 | 36 | F | NR | 4 years | NR | E. coli | 14 weeks | Improved |

| Mookerji et al[21], 2018 | 58 | M | Polycystic kidney disease | 6 months | Yes | E. coli, Enterobacter cloacae | 1 month | Kidney failure |

| Pirojsakul et al[22], 2015 | 14 | F | Vesico-ureteral reflux | 1 year | NR | E. coli | NR | NR |

| Keitel et al[23], 2014 | 23 | F | GN | 36 days | Yes | E. coli | 28 days | Kidney failure |

| Honsova et al[24], 2012 | 31 | F | DKD | 12 years | Yes | E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus | NR | Improved |

| Augusto et al[25], 2008 | 56 | F | Unknown | 11 months | No, prior transplant | E. coli | 10 weeks | Improved |

| Puerto et al[26], 2007 | 45 | F | NR | 2 years | NR | E. coli | None | Kidney failure |

| Pusl et al[27], 2006 | 43 | F | DKD | 2 years | NR | E. coli | 2 months | Improved |

| McKenzie et al[28], 1996 | 29 | F | GN | 8 years | NR | NR | Long-term | Improved |

| Stern et al[29], 1994 | 55 | F | GN | 3 years | No | E. coli | Long-term | Improved |

| Osborn et al[30], 1977 | 46 | F | Pyelonephritis | 15 months | No | E. coli, psoriasis vulgaris | 1 month | Improved |

| Ref. | Anatomical location | Age, gender | Native disease | Time after transplant | Prior rejection | Organism |

| Boo et al[31], 2023 | Native kidney | 40, F | End stage kidney disease | 32 weeks | No | E. coli |

| Coulibaly et al[32], 2023 | Colon | 62, M | GN | NR | NR | NR |

| Biggar et al[6], 1985 | Abdominal wall | 32, M | Reflux | 16 months | Yes | E. coli |

| Nieto-Ríos et al[33], 2017 | Bladder | 45, F | Preeclampsia | 2 years | NR | E. coli |

| Graves et al[9], 2014 | Bladder | 56, F | GN | 1 year | Yes | E. coli |

| Merritt et al[34], 1985 | Bladder | 64, F | NR | 3 years | NR | NR |

| Deguchi et al[35], 1985 | Bladder | 22, F | GN | 1 year | NR | E. coli, Proteus mirabilis, K. pneumoniae |

| Sian et al[36], 1981 | Bladder | 52, F | PKD | 17 months | No | NR |

| Arnesen et al[37], 1977 | Bladder | 37, F | NR | 6 months | No | E. coli, Corynebacterium spp. |

| Mitchell et al[38], 2019 | Gastrointestinal | 72, F | FSGS | 10 months | NR | NR |

| Ghaith et al[39], 2018 | Gastrointestinal | 75, M | DKD, HTN | NR | Yes | NR |

| Koklu et al[40], 2018 | Gastrointestinal | 51, F | HTN | 11 years | NR | NR |

| Mousa et al[41], 2017 | Gastrointestinal | 68, M | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Bae et al[42], 2013 | Gastrointestinal | 55, F | GN | 11 years | No | NR |

| Shah et al[43], 2010 | Gastrointestinal | 45, M | DKD | 3 years | Yes | NR |

| Yousif et al[44], 2006 | Gastrointestinal | 40, M | PKD | 15 months | NR | E. coli |

| Berney et al[45], 1999 | Gastrointestinal | 52, M | PKD | 9 years | No | E. coli |

| Macdonald et al[46], 2019 | Groin | 48, M | Reflex | 5 months | No | E. coli |

| Afonso et al[47], 2013 | Groin | 51, M | FSGS | 2 years | NR | Providentia spp., Candida albicans |

| Olivier et al[48], 2022 | Groin | 70, M | DKD, HTN | 2 years | NR | E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Lowitt et al[49], 1996 | Perineum | 51, M | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | 14 months | NR | Streptococci spp., K. pneumoniae, Enterococcus spp. |

| Leão et al[50], 2012 | Perineum | 37, M | Reflux | 15 years | Yes | Burkholderia cepacia |

| Ifudu and Delaney[51], 1994 | Prostate | 60, M | HTN | 1 year | NR | E. coli, Serratia marcescens |

| Lococo et al[52], 2016 | Pulmonary | 67, M | NR | 1 year | NR | Rhodococcus equi |

| Biggar et al[6], 1985 | Pulmonary | 44, M | GN | 31 months | NR | E. coli |

| Addison[53], 1986 | Skin (eyelid) | 35, M | Pyelonephritis | 3.5 years | Yes | E. coli |

| Lowitt et al[49], 1996 | Skin (temple) | 67, M | DKD, HTN | 1 year | NR | E. coli, Streptococcus spp. |

| Schwob et al[54], 2015 | Tongue | 70, M | NR | NR | NR | E. coli |

We noted several trends and observations based on the Malakoplakia cases involving the kidney allograft. E. coli was the most common organism, accounting for infections in 23 out of 27 cases (85.1%). Organisms such as Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter aerogenes, Klebsiella pneumoniae, psoriasis vulgaris, and S. aureus were found in a few cases, along with E. coli. In two cases, the organism was not reported.

Malakoplakia was more likely to affect the kidney allografts in female recipients (23/27 cases), while it was more likely to occur in locations other than the kidney allograft in male recipients. The recipients' age varied between 14 and 74 in the literature.

The clinical presentation of malakoplakia varied based on its location and severity. When occurring in the kidney allograft, malakoplakia can present with unilateral kidney dysfunction, allograft pain, dysuria, lower urinary tract symptoms, or a palpable mass.

Recipients may also develop perinephric abscesses, hydronephrosis, or pyelonephritis. Laboratory results that may clue clinicians toward malakoplakia include elevated creatinine, decreased glomerular filtration rate, elevated white blood cell count, urinalysis suggestive of UTI, and a urine culture positive for bacterial organisms. As Patel et al[15] reported, hypercalcemia may rarely be seen. Imaging may show an enlarged allograft with a possible mass.

Biopsy serves as the best diagnostic tool for malakoplakia diagnosis. On gross examination, malakoplakia will appear as white or yellow patches, calcified plaques, or masses of the kidney autograft. Histopathologic examination reveals von Hansemann cells, enlarged macrophages with eosinophilic cytoplasm, and Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, 2-10 mm lesions within the cytoplasm of macrophages with a “bird’s eye” appearance, on light microscopy (Figure 1)[15]. The presence of periodic acid Schiff positive granules in the macrophages and CD 68 positivity can also confirm the diagnosis if the lesions stain negative for calcium in the von Kossa stain[7]. Sometimes, a repeat biopsy may be considered as these lesions may not be apparent early in the disease course[8].

The data reports a mix of recipient outcomes based on the recipient’s history of prior transplant rejection episodes among recipients with kidney allograft malakoplakia. Eight out of 27 cases reported prior transplant rejection or concomitant rejection, Eight out of 27 did not report prior rejection, and eleven out of 27 did not report this data. Regardless of a recipient’s history of transplant rejection, similar outcomes were noted in improvement vs kidney decline. Thus, prior or concurrent rejection may not present any clinical value in predicting recipient outcomes.

The time from kidney transplant to the onset of malakoplakia was variable among the cases, from 36 days to 12 years. No trends were found in linking infection to time after transplant, and thus, it is essential to note that infections can occur at any point, with a need for long-term surveillance.

Most recipients exhibited clinical improvement after successfully identifying kidney allograft malakoplakia, with 21 out of 27 cases (77.7%) showing improvement following treatment. Two of the cases reported no outcome, and 4/27 of the cases resulted in kidney failure. In the four cases where recipients developed kidney failure, the causes were often multifactorial, with recipients experiencing recurrent infections, advanced malakoplakia, unresponsive to medical therapy, and advanced disease presentation. Understanding these cases of malakoplakia post-kidney transplant underscores the importance of tailored management strategies to achieve favorable outcomes, as the majority of post-transplant infections exhibited positive results with appropriate treatment.

Among the relevant cases, treatment of the condition included initiating antibiotics, reduced immunosuppression therapy, and, rarely surgery. Antibiotics were selected based on susceptibility. TMP/SMX and fluoroquinolones are the preferred antibiotic choices in managing malakoplakia due to their ability to accumulate inside the macrophages. Bethanechol chloride has been shown to increase cGMP levels and can be considered an additive treatment in addition to antibiotics[7]. The antibiotic duration was based on treatment response, and the treatment response to antibiotics varied amongst the reported cases, ranging from 22 days to long-term therapy. Recipients were continued on long-term antibiotics even after response to a short-term treatment. Antibiotic therapy may be insufficient in advanced cases, and surgical intervention may be appropriate[55]. Such cases are rare and present as pseudotumor with mass effect. Antibiotics are crucial in the appropriate management of malakoplakia, and the recipients need to be maintained on prolonged antibiotic therapy even after the surgical resection of the lesions.

In some cases, it was found that reducing immunosuppression therapy may improve the response to antibiotic therapy[7]. Some immunosuppressive therapies may lead to malakoplakia due to leukotoxicity. Leukocyte toxic immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine can increase the risk for malakoplakia. Purine synthesis inhibitors such as mycophenolate mofetil should be limited during the active treatment of malakoplakia. Episodes of rejection requiring heightened immunosuppression also increase the risk of malakoplakia. Overall, malakoplakia has a good prognosis with early identification and treatment. Proper management of immunosuppression and appropriate antibiotic therapy are crucial for resolving this condition[7,12,15].

Due to its rarity, atypical presentation, and progression, malakoplakia is challenging to diagnose. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of unexplained kidney allograft dysfunction, allograft, or systemic mass in recipients with kidney transplants. Biopsy and histological examinations, such as those presented in this case series, are crucial for diagnosing Malakoplakia.

E. coli is the most common infection associated with malakoplakia in kidney transplant recipients. Malakoplakia involving the kidney allograft is common in females, whereas malakoplakia involving other internal organs is more common in males. Most recipients had favorable outcomes with appropriate management that involved administering antibiotics, adjusting immunosuppression, and, rarely resection.

Overall, this paper emphasizes the importance of having awareness and continued research in transplant nephrology as the risk for malakoplakia and its complications increases dramatically. It should be assessed in recipients with recurrent infections and unexplained loss of allograft function post-transplant. There is an increased need for guideline-based principles to address malakoplakia in kidney transplant recipients.

| 1. | Samian C, Ghaffar S, Nandapalan V, Santosh S. Malakoplakia of the parotid gland: a case report and review of localised malakoplakia of the head and neck. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101:309-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gliddon T, Proudmore K. Cutaneous Malakoplakia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Damjanov I, Katz SM. Malakoplakia. Pathol Annu. 1981;16:103-126. [PubMed] |

| 4. | SCOTT EV, SCOTT WF Jr. A fatal case of malakoplakia of the urinary tract. J Urol. 1958;79:52-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Biggar WD, Keating A, Bear RA. Malakoplakia: evidence for an acquired disease secondary to immunosuppression. Transplantation. 1981;31:109-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Biggar WD, Crawford L, Cardella C, Bear RA, Gladman D, Reynolds WJ. Malakoplakia and immunosuppressive therapy. Reversal of clinical and leukocyte abnormalities after withdrawal of prednisone and azathioprine. Am J Pathol. 1985;119:5-11. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Yim SH, Min EK, Kim HJ, Lim BJ, Huh KH. Successful treatment of renal malakoplakia via the reduction of immunosuppression and antimicrobial therapy after kidney transplantation: a case report. Korean J Transplant. 2022;36:289-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Szołkowska M, Langfort R, Szczepulska EM, Bestry I, Religioni J. [Pulmonary malakoplakia and Rhodococcus equi infection. A report of two cases and review]. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2007;75:398-404. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Graves AL, Texler M, Manning L, Kulkarni H. Successful treatment of renal allograft and bladder malakoplakia with minimization of immunosuppression and prolonged antibiotic therapy. Nephrology (Carlton). 2014;19 Suppl 1:18-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vishwajeet V, Nalwa A, Jangid MK, Choudhary GR, Khera P, Bajpai N, Elhence PA. Renal Allograft Malakoplakia Presenting as a Pseudotumoral Lesion. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2023;34:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rustom DS, Wall BM, Talwar M. Malakoplakia in kidney transplant causing severe hydronephrosis and successful treatment with antibiotics and lowering immunosuppression. Transpl Infect Dis. 2023;25:e14158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Triozzi JL, Rodriguez JV, Velagapudi R, Fallahzadeh MK, Binari LA, Paueksakon P, Fogo AB, Concepcion BP. Malakoplakia of the Kidney Transplant. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:680-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Park S, Hojong P, Hong C, Kyung P, Jongha P, Don YK, Jong L. Malakoplakia after kidney transplantation. KJT. 2020;34:S105-S105. |

| 14. | Lee EJ, Park H, Park SJ, Cho HR, Park KS, Park J, Yoo KD, Lee JS, Kim M, Cha HJ. Outgrowing skin involvement in malakoplakia after kidney transplantation: A case report. Transplant Proc. 2022;54:1627-1631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Patel MR, Thammishetti V, Agarwal S, Lal H. Renal graft malakoplakia masquerading post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:e244228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kalimuthu LM, Ora M, Nazar AH, Gambhir S. Malakoplakia Presenting as a Mass in the Transplanted Kidney: A Malignancy Mimicker on PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2021;46:60-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kinsella PM, Smibert OC, Whitlam JB, Steven M, Masia R, Gandhi RG, Kotton CN, Holmes NE. Successful use of azithromycin for Escherichia coli-associated renal allograft malakoplakia: a report of two cases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40:2627-2631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tan XY, Polishchuk, S, Zaky Z. Renal Allograft Malakoplakia Successfully Treated with Prolonged Antibiotic Therapy and Reduction of Immunosuppression. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77:655-655. |

| 19. | Khojah S. A Review Article on Genitourinary Malakoplakia after Kidney Transplantation. Saudi J Med Pharm Sci. 2020;6. |

| 20. | Yasin SMA, Baqdunes M, Sureshkumar K. Renal allograft malakoplakia: favorable outcome with early diagnosis and prolonged antibiotic therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71:598. |

| 21. | Mookerji N, Skinner T, Mcalpine K, Warren J. Case - Malakoplakia in a 58-year-old male following living donor renal transplantation. Can Urol Assoc J. 2019;13:E19-E21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pirojsakul K, Powell J, Sengupta A, Desai D, Seikaly M. Mass lesions in the transplanted kidney: Questions. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:1107-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Keitel E, Pêgas KL, do Nascimento Bittar AE, dos Santos AF, da Cas Porto F, Cambruzzi E. Diffuse parenchymal form of malakoplakia in renal transplant recipient: a case report. Clin Nephrol. 2014;81:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Honsova E, Lodererova A, Slatinska J, Boucek P. Cured malakoplakia of the renal allograft followed by long-term good function: a case report. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2012;156:180-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Augusto JF, Sayegh J, Croue A, Subra JF, Onno C. Renal transplant malakoplakia: case report and review of the literature. NDT Plus. 2008;1:340-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Puerto IM, Mojarrieta JC, Martinez IB, Navarro S. Renal malakoplakia as a pseudotumoral lesion in a renal transplant patient: a case report. Int J Urol. 2007;14:655-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pusl T, Weiss M, Hartmann B, Wendler T, Parhofer K, Michaely H. Malacoplakia in a renal transplant recipient. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17:133-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | McKenzie KJ, More IA. Non-progressive malakoplakia in a live donor renal allograft. Histopathology. 1996;28:274-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Stern SC, Lakhani S, Morgan SH. Renal allograft dysfunction due to vesicoureteric obstruction by nodular malakoplakia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9:1188-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Osborn DE, Castro JE, Ansell ID. Malakoplakia in a cadaver renal allograft: a case study. Hum Pathol. 1977;8:341-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Boo Y, Yim H, Bang JB. Malakoplakia in the recipient's native kidney after kidney transplantation. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2023;42:149-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Coulibaly ZI, Fernandez Y Viesca M, Demetter P. Multiple Ulcerated and Polypoid Lesions in a Renal Transplant Patient. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:840-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nieto-Ríos JF, Ramírez I, Zuluaga-Quintero M, Serna-Higuita LM, Gaviria-Gil F, Velez-Hoyos A. Malakoplakia after kidney transplantation: Case report and literature review. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Merritt AJ, Thiryayi SA, Rana DN. Malakoplakia diagnosed by fine needle aspiration (FNA) and liquid-based cytology (LBC) presenting as a pararenal mass in a transplant kidney. Cytopathology. 2014;25:276-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Deguchi T, Kuriyama M, Shinoda I, Maeda S, Takeuchi T, Sakai S, Ban Y, Nishiura T. Malakoplakia of urinary bladder following cadaveric renal transplantation. Urology. 1985;26:92-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sian CS, McCabe RE, Lattes CG. Malacoplakia of skin and subcutaneous tissue in a renal transplant recipient. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:654-655. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Arnesen E, Halvorsen S, Skjorten F. Malacoplakia in a renal transplant. Report of a case studied by light and electron microscopy. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1977;11:93-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Mitchell A, Dugas A. Malakoplakia of the colon following renal transplantation in a 73 year old woman: report of a case presenting as intestinal perforation. Diagn Pathol. 2019;14:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ghaith J, Allard JP, Serra S. S1690 A Case of Rhodococcus Related Colonic Malakoplakia in a Renal Transplant Patient. ACG. 2020;115:S869. |

| 40. | Koklu H, Imamoglu E, Tseveldorj N, Sokmensuer C, Kav T. Chronic Diarrhea Related to Colonic Malakoplakia Successfully Treated with Budesonide in a Kidney Transplant Recipient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1906-1908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Mousa OY, Corral JE, Nassar A, Wang MH. Colonic Mass and Chronic Diarrhea in a Renal Transplant Patient: An Uncommon Case of Malakoplakia: 1441. ACG. 2017;112:S783. |

| 42. | Bae GE, Yoon N, Park HY, Ha SY, Cho J, Lee Y, Kim KM, Park CK. Silent Colonic Malakoplakia in a Living-Donor Kidney Transplant Recipient Diagnosed during Annual Medical Examination. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:163-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Shah MB, Sundararajan S, Crawford CV, Hartono C. Malakoplakia-induced diarrhea in a kidney transplant recipient. Transplantation. 2010;90:461-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yousif M, Abbas Z, Mubarak M. Rectal malakoplakia presenting as a mass and fistulous tract in a renal transplant patient. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56:383-385. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Berney T, Chautems R, Ciccarelli O, Latinne D, Pirson Y, Squifflet JP. Malakoplakia of the caecum in a kidney-transplant recipient: presentation as acute tumoral perforation and fatal outcome. Transpl Int. 1999;12:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Macdonald RA, Moyes C, Clancy M, Douglas P. Cutaneous malakoplakia presenting as a groin swelling and graft failure. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:e227460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Afonso JP, Ando PN, Padilha MH, Michalany NS, Porro AM. Cutaneous malakoplakia: case report and review. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:432-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Olivier N, Maiza H, Turmel JM, Baubion É. Malakoplakie cutanée: une pseudo-tumeur rare à ne pas méconnaître chez l’immunodéprimé [Cutaneous malakoplakia: A rare pseudo- tumor to know in immunocompromised patients]. Nephrol Ther. 2022;18:213-215. |

| 49. | Lowitt MH, Kariniemi AL, Niemi KM, Kao GF. Cutaneous malacoplakia: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Leão CA, Duarte MI, Gamba C, Ramos JF, Rossi F, Galvão MM, David-Neto E, Nahas W, Shikanai-Yasuda MA, Pierrotti LC. Malakoplakia after renal transplantation in the current era of immunosuppressive therapy: case report and literature review. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14:E137-E141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Ifudu O, Delaney VB. Malacoplakia of the prostate in a renal transplant recipient. A complicated course. ASAIO J. 1994;40:238-240. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Lococo F, Montanari G, Mengoli MC, Ferrari F, Spagnolo P, Rossi G. Hemoptysis and Progressive Dyspnea in a 67-Year-Old Woman with History of Renal Transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e12-e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Addison DJ. Malakoplakia of the eyelid. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:1064-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Schwob E, Bouaziz JD, Saussine A, Bagot M, Dionyssopoulos A, Rigolet A. [Malakoplakia of the submandibular gland in a renal transplant patient]. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac Chir Orale. 2015;116:384-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Kitajima K, Koike J, Koizumi H, Udagawa T, Kudo H, Nakazawa R, Sasaki H, Tsutsumi H, Miyano S, Sato Y, Chikaraishi T. [Case of renal parenchymal malakoplakia presenting as sepsis and treated with nephrectomy]. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;102:721-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |