TO THE EDITOR

Dengue fever (DF) has become an escalating public health threat in Nepal, with rising morbidity and mortality rates and several outbreaks reported in recent years[1]. This climate-sensitive viral disease, transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, presents a significant challenge for healthcare providers and policymakers in the country[1]. DF is caused by the dengue virus (DENV), a single-stranded RNA virus of the Flavivirus genus in the Flaviviridae family. DF can cause a range of health issues, from mild symptoms to life-threatening conditions such as dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), a severe form characterized by bleeding, blood plasma leakage, and low platelet count, or dengue shock syndrome (DSS), the most severe form, that occurs when the circulatory system fails due to severe plasma leakage. Both DHF and DSS are caused by one of the four serotypes (DENV1-4)[2]. Globally, the prevalence of DF has been increasing, with nearly half of the world's population at risk. It is estimated that 390 million people are infected annually, with 96 million developing severe clinical manifestations[3]. Several factors associated with mosquito invasion and increased travel within the population are believed to drive the epidemic’s expansion, elucidating the dissemination of the DENV to new locations[4]. This study investigated the impact of climate change on DF outbreaks in Nepal.

CURRENT STATUS AND TRENDS OF DENGUE IN NEPAL

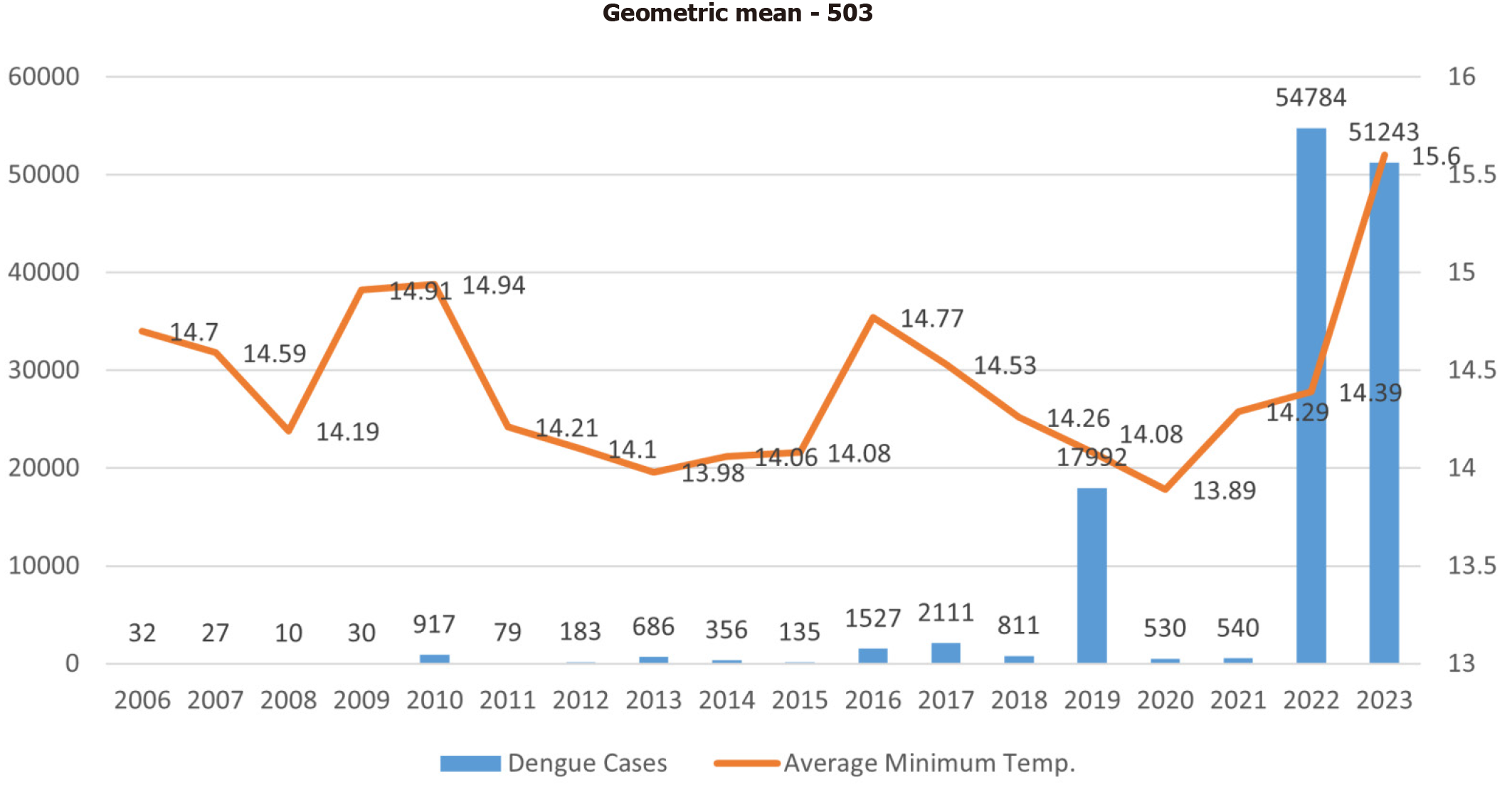

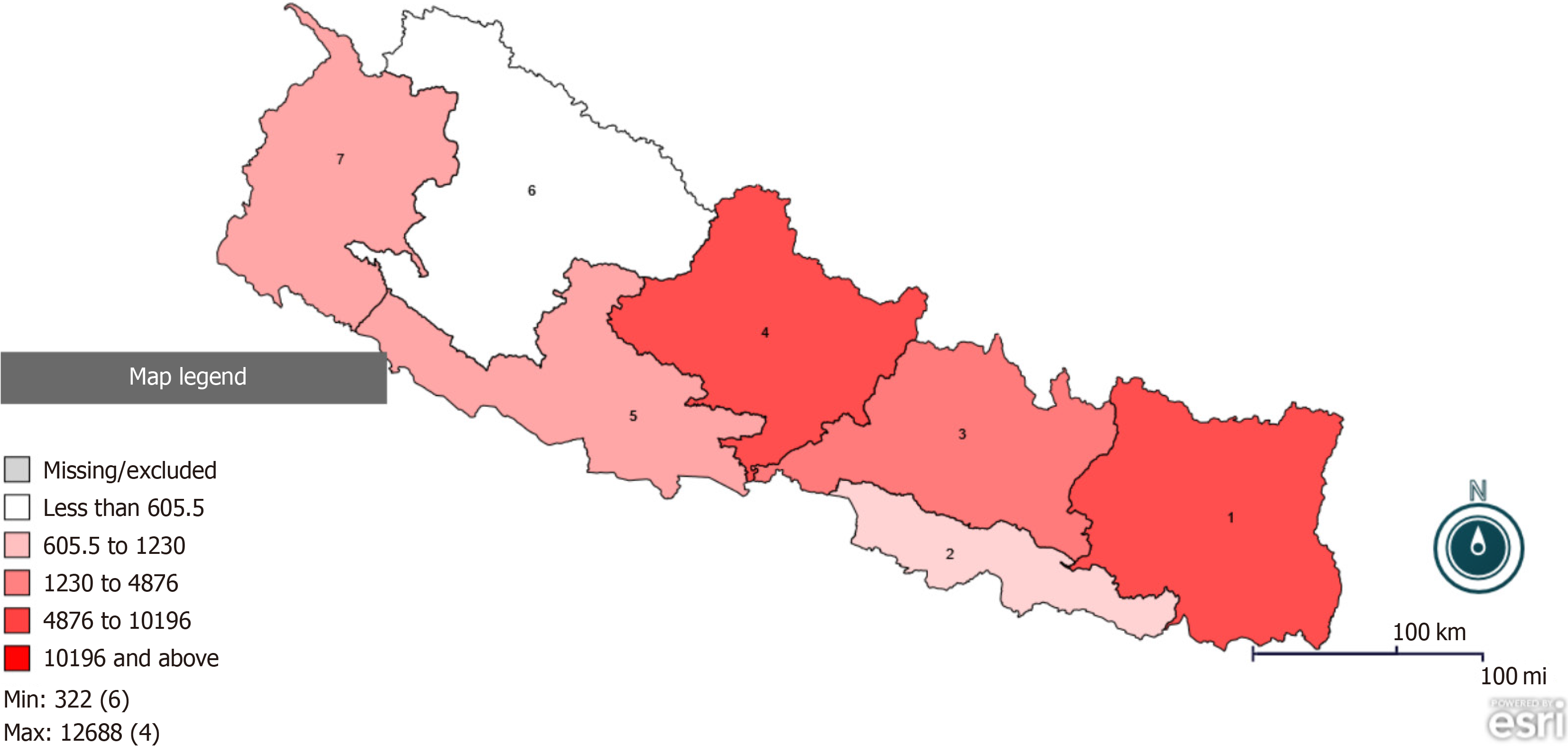

Since the first report in 2004, Nepal has witnessed a sharp increase in DF cases, with the geometric mean calculated rising by 503 between 2006-2023 (Figure 1)[1,5]. In 2019, the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) documented 17992 confirmed dengue cases, resulting in six deaths. However, by 2022, the situation worsened dramatically, with 54784 cases and 88 fatalities reported across all seven provinces and 77 districts of Nepal[6]. All four serotypes of DENV have been in circulation since 2006, and the 2022 epidemic was primarily attributed to serotypes 1, 2, and 3[7]. This 2022 outbreak was the worst the country had experienced since the first outbreak in 2006, nearly triple the number of cases reported in 2019. By December 15, 2023, a total of 51243 cases of dengue have been recorded across 77 districts, resulting in 20 deaths. Notably, Koshi Province reported the highest count (26021), followed by Gandaki Province (12688) and Bagmati Province (7704) along with other provinces (Figure 2)[8]. While dengue was previously confined to the warmer lowland regions of Nepal, recent data show its prevalence in upland hilly regions, a shift attributed to climate change and rapid urbanization[9].

Figure 2 Distribution of dengue cases in Nepal in 2023.

1: Koshi Province; 2: Madhesh Province; 3: Bagmati Province; 4: Gandaki Province; 5: Lumbini Province; 6: Karnali Province; 7: Sudurpashchim Province. Data source: https://edcd.gov.np/section/dengue-control-program.

Climate change is one of the greatest threats to global public health, particularly through its effects on the spread of vector-borne diseases like DF. Nepal, located in the Himalayan region, is particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, raising concerns about its influence on dengue outbreaks[10]. Changes in temperature, precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events are altering the ecology of Aedes mosquitoes, the primary vectors for dengue transmission[11]. Over the past 40 years, Nepal’s average annual maximum temperature has increased by 0.056 °C, with more pronounced warming at higher altitudes[12]. Rising temperatures accelerate mosquito development, enhance virus replication, and facilitate dengue transmission in areas previously unaffected by the disease. Changes in precipitation, including increased rainfall and erratic weather patterns, provide more breeding sites, particularly in urban areas with poor drainage, while higher humidity levels extend mosquito lifespan and activity. These climatic changes have extended the dengue transmission season and expanded the spread of the disease, complicating public health efforts to control outbreaks[4,13]. Recent studies indicate that alterations in the diurnal temperature range (DTR) hold greater significance than shifts in average temperature concerning the transmission of dengue[4]. A wider DTR can reduce transmission by shortening mosquito lifespans and lowering infection rates, while optimal transmission occurs within a narrow temperature range of 27-31°C. Seasonal variations in DTR influence mosquito survival and infection dynamics, which, in turn affect outbreak patterns[14,15]. To address the impacts of climate change on dengue in Nepal, effective strategies must include both climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts. Climate change adaptation measures involve strengthening the healthcare system to better manage dengue cases, increasing public awareness about dengue prevention, and enhancing vector control measures. Mitigation efforts target the root causes of climate change.

The government of Nepal has initiated several programs to combat dengue, including public awareness campaigns, healthcare provider training on dengue diagnosis and management, and strengthening vector control measures such as conducting search-and-destroy drives targeting mosquito breeding sites. The MoHP has also established a national dengue control program to coordinate among stakeholders (EDCD|Dengue Control Program). Despite these initiatives, the spread of dengue continues to increase annually, highlighting the need for improved strategies at the national level[16]. The failure to control the annual spread of dengue in Nepal can be attributed to inadequate community participation, inconsistent vector control efforts, and the challenges posed by rapid urbanization and climate change. To improve dengue control in Nepal, future plans should focus on enhancing community engagement through sustained education campaigns, ensuring consistent and integrated vector control efforts across districts, and addressing the impacts of urbanization and climate change. Strengthening surveillance systems and fostering collaboration between local authorities and health agencies will also be critical for improving management and prevention efforts.

Additionally, research and innovations are crucial in developing effective vaccines and antiviral drugs for dengue. Investigating the genetic diversity of the DENV and the Aedes mosquito population in Nepal can aid in the creation of targeted prevention and control strategies.

CONCLUSION

Dengue outbreaks are an increasing public health threat in Nepal, with increasing morbidity and mortality. Since 2004, cases have surged, with serotypes 1, 2, and 3, being the most prevalent, highlighting the need for urgent action. The government, healthcare providers, policymakers, researchers, and communities must collaborate to develop and implement comprehensive strategies that integrate climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts to reduce the burden of dengue. Together, we can address the escalating dengue burden and mitigate its impact on public health, working toward a future where dengue is effectively controlled and the health of the population is safeguarded in Nepal.