Published online Dec 25, 2024. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v13.i4.93721

Revised: August 5, 2024

Accepted: September 3, 2024

Published online: December 25, 2024

Processing time: 226 Days and 21.9 Hours

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is categorized as one of the smallest enveloped DNA viruses and is the prototypical virus of the Hepatoviridae family. It is usually transmitted through body fluids such as blood, semen, and vaginal secretions. The majority (more than 95%) of immunocompetent adults infected with HBV spontaneously clear the infection. In the context of the high prevalence of HBV infection in Albania, the research gap is characterized by the lack of studies aimed at advancing the current understanding and improving the prevailing situation. The main objective of this study was to address the low rate of HBV diagnosis and the lack of a comprehensive national program to facilitate widespread diagnosis.

To analyze the prevalence of HBV infection in Albania and elucidate the persis

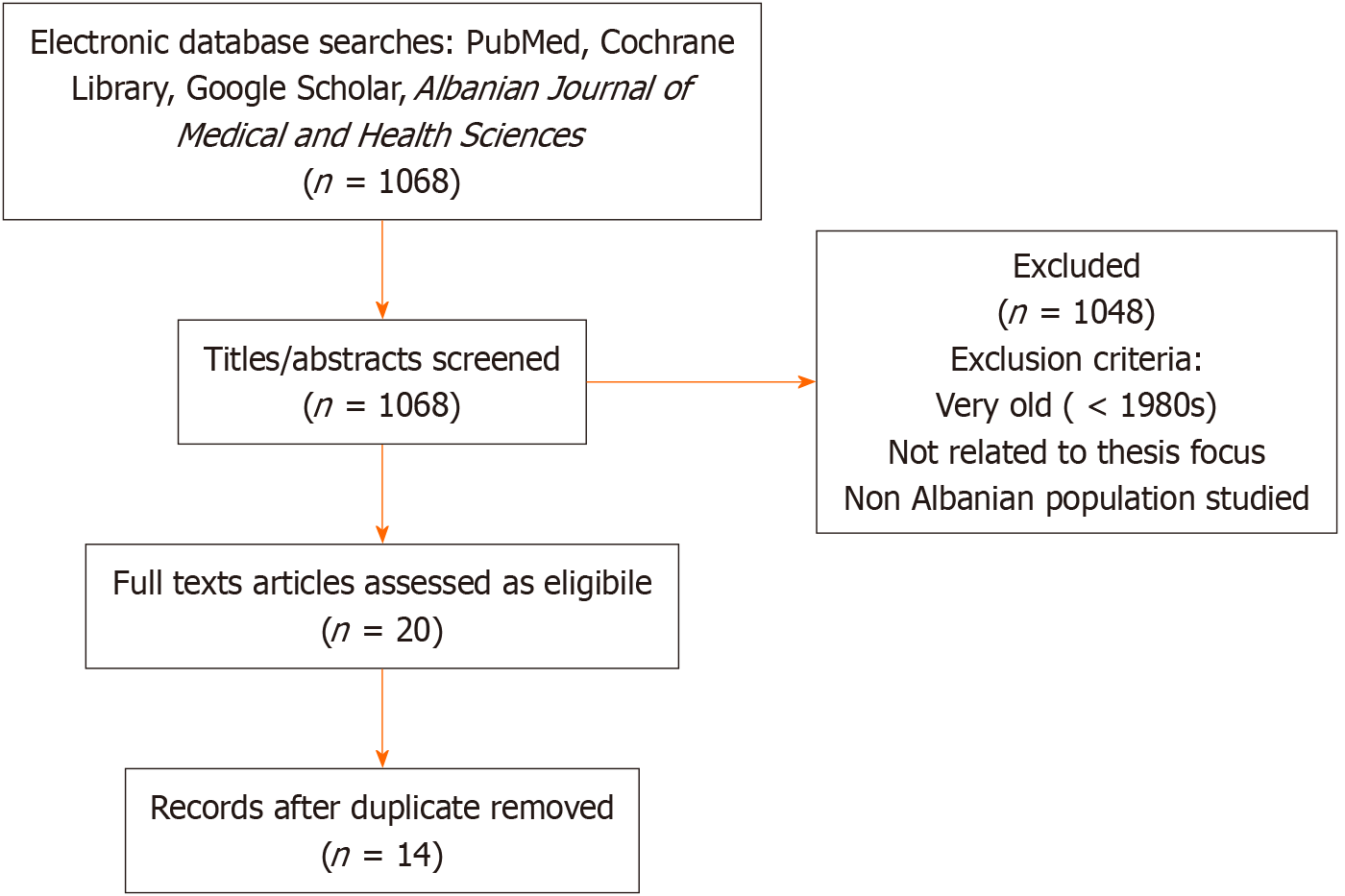

Using a systematic literature review, we collected existing research on the epidemiology of HBV in Albania from PubMed, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and Albanian Medical Journals, focusing on studies published after the 1980s and conducted solely in the Albanian population.

The findings reveal a dynamic shift in HBV prevalence in Albania over several decades. Initially high, the prevalence gradually declined following the implementation of screening and vaccination programs. However, the prevalence rates have remained notably high, exceeding 8% in recent years. Contributing factors include vertical transmission, inadequate healthcare infrastructure, and challenges in screening and diagnosis. Studies among Albanian refugees in neighboring countries also reported high prevalence rates, emphasizing the need for transnational interventions. Despite advancements in screening, vaccination, and healthcare infrastructure, Albania continues to face a substantial burden of HBV infection.

The persistence of high prevalence underscores the complexity of the issue, requiring ongoing efforts to ensure a comprehensive understanding and effective mitigation. Addressing gaps in vaccination coverage, improving access to screening and diagnosis, and enhancing public awareness are crucial steps toward reducing HBV prevalence in Albania.

Core Tip: This study aimed to comprehensively analyze the prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in Albania and elucidate the persistently high prevalence despite implemented efforts and measures.

- Citation: Jaho J, Kamberi F, Mechili EA, Bicaj A, Carnì P, Baiocchi L. Review of Albanian studies suggests the need for further efforts to counteract significant hepatitis B virus prevalence. World J Virol 2024; 13(4): 93721

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v13/i4/93721.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v13.i4.93721

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is classified as one of the smallest enveloped DNA viruses and serves as a prototype within the Hepadnaviridae family.

It is often transmitted through body fluids such as blood, semen, and vaginal secretions. The majority (more than 95%) of immunocompetent adults infected with HBV can clear the infection spontaneously[1,2].

HBV infection is highly variable in both presentation and severity. Some people clear the infection spontaneously, while others endure a lifetime of chronic complications, including hepatitis, cirrhosis, and cancer[3].

Serological markers of HBV infection include hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), indicating active infection; hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), indicating active viral replication; anti-HBe, reflecting loss of HBeAg synthesis due to immunologic containment or viral gene mutations; anti-HBc, indicating past or current infection; and anti-HBs, which serve as a marker for recovery from acute infection or vaccination-induced immunity[4,5].

The epidemiology of hepatitis B exhibits significant geographical variation, which is a distinctive aspect of its prevalence patterns. At the same time, it is one of the most pervasive infectious diseases on a global scale[6]. According to estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) 2019[7], the global burden of chronic hepatitis B was substantial, encompassing approximately 296 million people. This prevalence was accompanied by an annual incidence of 1.5 million new infections.

The epidemiology of hepatitis B can be described in terms of the prevalence of HBsAg in a population, broadly classified into high- (> 8% HBsAg prevalence), intermediate- (2%–7%), and low-prevalence areas (< 2%)[8].

There is a compelling association between the route of transmission, the genotype of HBV, and the epidemiological distribution of HBV infection in various countries[9].

The implementation of a mass HBV immunization program was recommended by the WHO since 1991, and has dramatically decreased the prevalence of HBV infection in many countries[10].

The primary objective of this study was to discern trends in the prevalence of HBV in Albania and to elucidate the persistently high prevalence, despite concerted efforts and implemented measures.

The research gap within the context of the high prevalence of HBV in Albania is characterized by a lack of studies aimed at advancing current understanding and improving the prevailing situation. This deficiency is notably accentuated by the absence of a comprehensive national program, limited diagnostic initiatives, and an insufficient scale of diagnostic interventions. Addressing these gaps is imperative to inform evidence-based strategies for effective prevention and control of HBV in Albania.

The primary objective of this study was to address the infrequent diagnostic rates of HBV and the lack of comprehensive national programs facilitating widespread diagnosis. Furthermore, the study aimed to analyze factors that contribute to the persistent high incidence of HBV, despite sporadic diagnoses. This investigation will specifically explore key elements such as immunization, advances in hospital hygiene, improvements in diagnostic tools, increased accessibility to diagnostic services in public and private entities, and the availability of cost-effective vaccines. The overarching goal was to gain insight into the multifaceted dynamics that influence the incidence of HBV, ultimately forming strategies to improve diagnostic rates and mitigate the prevailing high prevalence.

This study employed a systematic literature review methodology to comprehensively analyze existing research on the epidemiology of HBV in Albania. The primary objective was to identify the prevalent trends and determine the causes that contribute to sustained high prevalence despite the implemented efforts. The research was conducted across PubMed, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and Albanian Medical Journals, with keywords used in English or Albanian language, depending on the database (Albanian language keywords exclusively for articles published in Albanian). The inclusion criteria encompass full papers and articles published after 1980s, focusing on studies/systematic literature reviews conducted solely in the Albanian population and specifically addressing the epidemiology of HBV in Albania.

The following keywords and terms were used in the PubMed Database: (1) Hepatitis B; (2) HBV prevalence; and (3) Albania. The search string utilized was as follows: (("hepatitis B" [All fields] OR "HBV" [all fields] OR ("hepatitis" [all fields] AND "B" [all fields])) AND ("prevalence" [all fields] OR "Albania" [all fields])). Results of the research are reported in Figure 1.

In Albania, viral hepatitis B has been and continues to be a serious public health problem.

The endemicity of hepatitis B is described by the prevalence of HBsAg in the general population in a given geographic area. The WHO has classified the prevalence of hepatitis B according to HBsAg expression as high- (> 8%), medium- (2-7%), and low-prevalence (< 2%) countries (< 2%)[8].

Official statistics show that, despite small fluctuations, the incidence of viral hepatitis in the period 1964-1990 was quite high, ranging from 200-400 cases per 100000 inhabitants[11]. Studies based on the electrophoresis method have found a HBsAg positivity rate of ~10% in the healthy population in Albania[11]. The implementation of the HBsAg screening program in Albania started around 1975, and since that time the incidence and prevalence of HBV have changed significantly toward improving the situation.

For years, the condition appeared worrying, since the incidence figures were higher in children and adolescents. In a study on the epidemiological situation of HBV (1985), it was emphasized that viral hepatitis in children has increased and specifically in 1977 it was found in 36%, in 1979 in 41%, and in 1981 in 47% of children with acute viral hepatitis admitted to Tirana Pediatric Hospital[12].

The study of the prevalence of hepatitis B in Albania was investigated in different contingents, including immigrants settled in Italy and Greece after the mass exodus of 1991 as a result of the major political events that swept the country.

In a study conducted in 1980, among other things, the presence of the Australia antigen was studied in different contingents of pregnant women. The percentage of carryover according to quarters I, II, and III was 4.4%, 4.3%, and 5%, respectively. This study aimed to study risk factors for HBV transmission and vertical mother-to-child transmission[13].

In 1993, a study was conducted on the epidemiology of viral hepatitis in Albania. The sample consisted of 545 patients from the general population in the period January to August 1993. Vertical transmission was also studied in 193 pregnant women. It was found that 18.3% of the patients who received (n = 100) the examination were positive for HBsAg[11].

Daleko et al[14] analyzed the marked prevalence of viral hepatitis in Albanian immigrants originating mainly from the south of Albania. In this study, 1025 refugees located mainly in the prefecture of Ioannina were evaluated. The prevalence of HBsAg was found to be 22.2%.

Similarly, a study on the prevalence of various markers of hepatitis was conducted in pregnant women who had migrated to Greece (1996)[15]. The study sample included 500 participants, of whom 67 pregnant women (13.4%) tested HBsAg+.

Greece and Italy are the two countries with the highest number of Albanians who emigrated after 1991. Studies similar to those conducted in Greece have also been conducted on Albanian immigrants in Italy. In a study conducted by Chironna et al[16], the seroprevalence of hepatitis B, C, and D was analyzed in 670 Albanian immigrants in southern Italy in 1997; 13.6% of them were positive for HBsAg, while the prevalence of anti-HBs was 47.6%.

The HEPAGA project, a Greek-Albanian research collaboration, aimed to detect hepatitis B in the young population of Albania. For this reason, 410 young people aged 14-20 years who lived in Albania from September 2001 to February 2002 were examined. In this study conducted by Katsanos et al[17], 49 participants who constituted 11.89% of the sample were positive for HBsAg.

Health workers are considered a risk group for parenteral infectious diseases. The aim of the study conducted by Kondili et al[18] was to assess the prevalence of HBV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) in Albanian health workers. The study noted that the prevalence of HBsAg in 480 participants was 8.1% while the prevalence of anti-HBc was 70%. In this study, the highest prevalence was observed in the age group of 20-30 years old (11.4%). This study concluded not only the high rate of HBV infection in healthcare workers but also the low vaccination coverage.

Elefsiniotis et al[19] evaluated the prevalence of serological markers in 1333 pregnant women living in Greece but of different nationalities; 30.6% of them had Albanian nationality. Among pregnant women of Albanian nationality, the prevalence of HBsAg was estimated to be 11%, while the prevalence of anti-HBc was 52%. This study highlighted that HBV infection is endemic in pregnant Albanian women.

One of the most important studies conducted on the epidemiology of HBV in Albania is the one conducted by Resuli et al[20] who noted that the prevalence of HBsAg and anti-HBs was 9.5% and 28%, respectively, demonstrating that despite the almost twofold decrease in the prevalence of HBsAg in the general population, Albania continues to remain a highly endemic country for HBV.

Milionis[21] conducted a study in young Albanian immigrants living in Greece to study the serological prevalence of HBV and HCV; 504 subjects aged 10-23 participated in the study. In this study, 11.7% of the patients were found to be positive for HBsAg.

Durro and Qyra[22] evaluated in a retrospective study the epidemiological trends of hepatitis B in 79274 blood donors during the period 1999-2009. The prevalence of HBsAg in the examined blood donors was 7.9%. According to the status of the blood donor, the prevalence of HBsAg was 10.5% in commercial blood donors, 8.1% in voluntary blood donors, and 8.6% in blood donors from family members. The prevalence of anti-HBc was 59.1%.

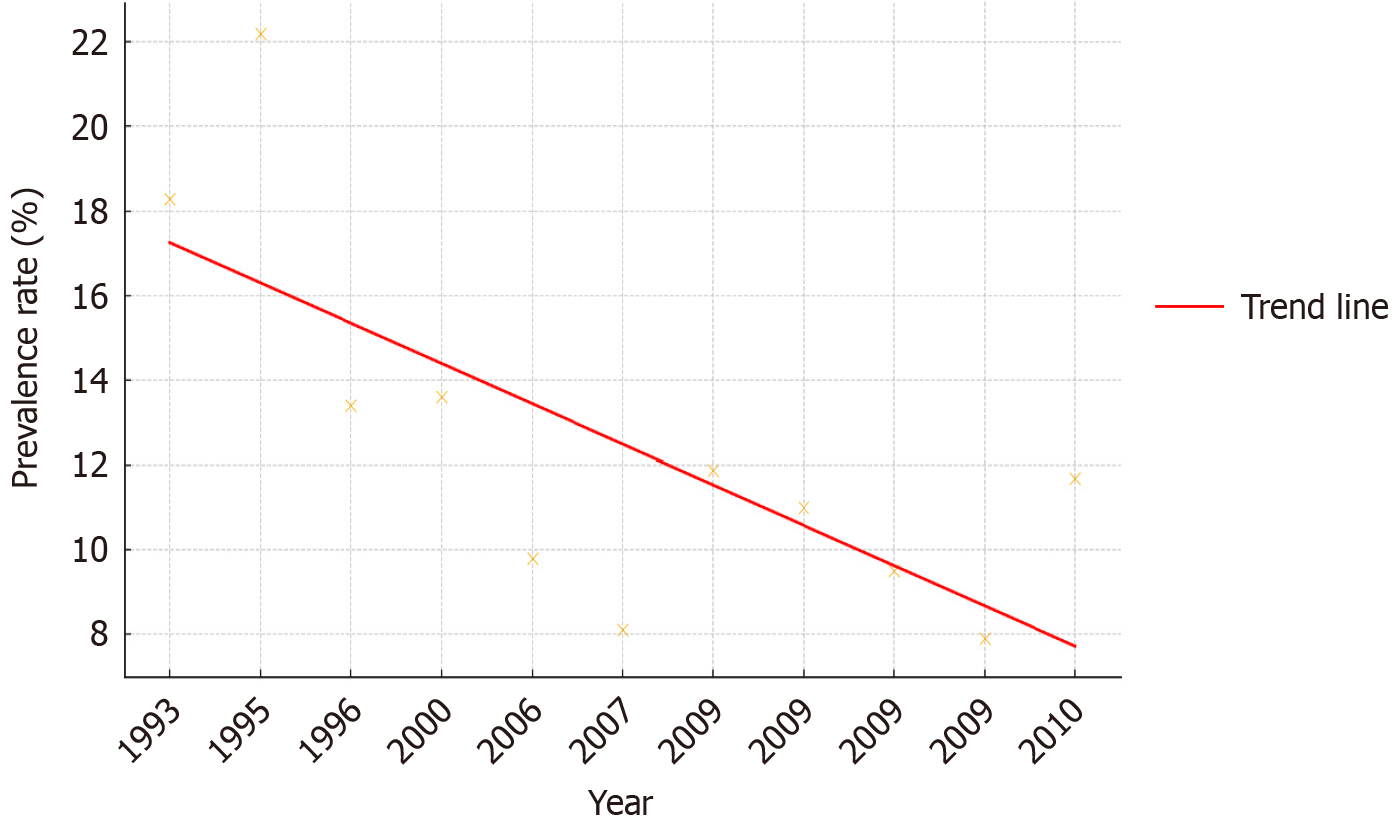

Limited studies have been conducted on the epidemiology of hepatitis B within the Albanian population; however, the available literature provides sufficient information on the prevalence of this virus. In particular, a significant portion of these studies have been conducted in neighboring countries, particularly Italy and Greece, which experienced increased immigration from Albania post-1990. A temporal analysis of these studies reveals a consistent decline in the prevalence of HBsAg. Nevertheless, it is imperative to underscore the scarcity of in-depth investigations conducted after 2009. Despite evident progress, Albania persists with a notable prevalence of hepatitis B exceeding 8%. The most relevant papers regarding HBV epidemiology in Albania are reported in Table 1.

| Ref. | Study region | Year | Age | Number of cases | Prevalence of HBsAg |

| Angoni et al[11] | Albania | 1993 | Adult | 545 | 18.3% |

| Dalekos et al[14] | Refugees (Greece) | 1995 | All ages | 1025 | 22.2% |

| Malamitsi-Puchner et al[15] | Albanian refugees | 1996 | Pregnant women | 500 | 13.4% |

| Chironna et al[16] | Albanian refugees (Italy) | 2000 | All ages | 670 | 13.6% |

| Papaevangelou et al[25] | Albanian (Greece) | 2006 | Pregnant women | 409 | 9.8% |

| Kondili et al[18] | Albania | 2007 | Health care workers | 480 | 8.1% |

| Katsanos et al[17] | Albania | 2009 | All ages | 410 | 11.89% |

| Elefsiniotis et al[19] | Albanian refugees | 2009 | Pregnant women | 408 | 11% |

| Resuli et al[20] | Albania | 2009 | All ages | 3880 | 9.5% |

| Durro and Qyra[22] | Albania | 2009 | Blood donors | 79274 | 7.9% |

| Milionis[21] | Albanian (Greece) | 2010 | 10-23 | 504 | 11.7% |

The prevalence of hepatitis B in Albania has exhibited dynamic shifts characterized by a sustained reduction in reported cases (Figure 2). This phenomenon can be attributed to the implementation of various policies and the variable influence of risk factors. Beyond the overarching decline in prevalence and incidence rates in successive years, there are discernible variations in various epidemiological aspects.

Zehender et al[23] demonstrated that genotype D2 made its entry into the Albanian population during the latter part of the 1960s. Research findings indicated a continual increase in the effective number of infections until the mid-1990s, at which point a plateau was reached.

This is reflected in a study conducted in children hospitalized for acute viral hepatitis at the Pediatric Hospital in Tirana. A notable increase in cases was observed, specifically in the year 1977, accounting for 36% of cases, in 1979 reaching 42%, and in 1981 escalating to 47% of cases[12].

The incidence of hepatitis B in Albania has been documented in a limited number of studies. Most of these studies have assessed the prevalence in various groups or in the general healthy population. The incidence of viral hepatitis during the years 1964-1990 was notably high, ranging between 200-400 cases per 100000 inhabitants. Meanwhile, data from the WHO indicate that the annual incidence of viral hepatitis (all forms combined) in Western European countries ranged from 10 to 50 cases per 100000 inhabitants.

These studies indicate that until the 1990s, the incidence and prevalence of HBsAg in Albania were notably high and experienced an upward trend during a specific time period[11].

In the aftermath of Albania's transition in the early 1990s, substantial emigration occurred, impacting not only Albania but also neighboring Italy and Greece. R. Angoni's 1993 study of 545 subjects revealed a notable 18.3% prevalence of HBsAg, indicating significant rates of liver infection. Additionally, 49% of subjects tested positive for anti-HBs, suggesting prior exposure or immunization[11].

Dalekos et al[14] conducted a study among Albanian refugees in Greece, estimating a prevalence of hepatitis B of 22.5% among 1025 subjects. Similarly, Roussos et al[24] found a comparable prevalence of 22.4% among a smaller sample of 76 Albanian subjects. Subsequent to national vaccination campaigns initiated in 1994, there was a notable decline in prevalence rates reported by studies among Albanian refugees in Greece and Italy, with figures dropping to 13.6%, 13.4%, and 9.8%, respectively[15,16,25].

Resuli et al[20] highlighted a significant decrease in HBV prevalence by 50%, estimating a prevalence of only 9.5% among 3880 subjects. Furthermore, the lowest prevalence was observed in a study of Albanian blood donors in 2009, where only 7.9% tested positive, marking a decrease from the prevalence of 9.1% reported in 1999[22]. Furthermore, Kondili et al[18] reported a prevalence of 8.1% among 480 Albanian healthcare workers[18].

Comparable studies conducted between 2009 and 2010 demonstrate a persistent prevalence of HBV ranging from 11% to 11.89%. Although indicating a decrease in previous prevalence rates, these findings still underscore a notably high prevalence of HBV within the examined population over this short period[17,19,21]. The analysis of trend and its statistic (analysis of covariance) are reported in Figure 2 and Table 2, respectively.

| Source | Type III sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | P value |

| Corrected model | 127.702 | 2 | 63.851 | 7.735 | 0.013 |

| Intercept | 1757.171 | 1 | 1757.171 | 212.864 | |

| Population | 5.079 | 1 | 5.079 | 0.615 | 0.455 |

| Year 2000 | 103.685 | 1 | 103.685 | 12.560 | 0.008 |

| Error | 66.039 | 8 | 8.255 | ||

| Total | 1914.742 | 11 | |||

| Corrected total | 193.741 | 10 |

The persistently high prevalence of HBV in Albania is the result of multifactorial influences, reflecting the ongoing challenges within the healthcare system and societal contexts. While past issues such as the lack of single-use medical devices in hospitals have been addressed to some extent, contemporary factors continue to contribute to the prevalence of HBV. Among these factors is the persistence of vertical transmission, where infected mothers can still pass the virus to their newborns during childbirth. Furthermore, challenges in access to healthcare services, including screening and vaccination programs, and lack of awareness of HBV transmission and prevention among the general population further exacerbate the prevalence of the virus in Albania.

Troja[13] found a direct correlation between the prevalence of HBV in pregnant women and the number of injections received[13]. This highlights the role of inadequate use of single-use medical devices in hospitals as a contributing factor to HBV transmission[13,15].

Several studies conducted on Albanian refugees in Italy or Greece have emphasized the significant impact of low socioeconomic status and the poor hygienic conditions experienced by its members on the high prevalence of HBV[14,15,17].

Vertical transmission, resulting from factors such as inadequate screening of pregnant women and the use of non-disposable medical equipment, played a significant role in the high prevalence of HBV[11,13]. Hospital practices in Albania also contributed due to poor medical and nursing standards[15]. Resuli et al[20] noted that the reduction in the prevalence of HBsAg after infant vaccination mainly stemmed from the prevention of perinatal HBV transmission, highlighting the role of vertical transmission in high prevalence.

The lack of a proper screening for blood and its products also contributed to this endemic prevalence. However, in a study conducted among Albanian blood donors, the prevalence of HBsAg decreased from 9.1% in 1999 to 7.9% in 2009, suggesting an improvement in the transfusion safety of blood and its products[22].

One of the most significant factors contributing to the high prevalence of HBV in Albania was the low coverage of HBV immunization. Numerous studies carried out among the Albanian population, both within Albania and in neighboring countries such as Italy and Greece, have highlighted the low vaccination rates. Despite efforts in prenatal screening and vaccination programs, gaps in coverage and inadequate administration of vaccine doses persist[16,24]. Chironna et al[16] found that the prevalence of HBV among children up to 10 years of age was 8.1%, indicating high vertical and horizontal transmission rates and underscoring the inadequacy of immunization efforts.

Despite a high percentage of women who underwent prenatal screening for HBsAg, certain factors, such as delivery in public hospitals and maternal illiteracy, were associated with some women not being tested[25]. Furthermore, Albania's potential higher endemicity of HBV infection compared to neighboring countries may contribute to the elevated prevalence observed among its population[17].

Furthermore, the absence of a nationwide surveillance campaign for HBV infections and the underestimation of vaccination programs exacerbated the situation. In a study, inefficiencies in the monitoring program were highlighted, indicating the need for improved data quality. To enhance the effectiveness of the system, a web-based reporting system, enhanced laboratory tests, and staff training are necessary measures to increase quality, efficiency, and overall usefulness[26].

The measures taken to combat HBV infection in Albania have been multifaceted, addressing various aspects of healthcare infrastructure, prevention, and awareness. Implementing more sensitive laboratory techniques for HBV marker detection, such as ELISA, has advanced diagnostic capabilities[11]. Moreover, vaccination programs targeting newborns, initiated in May 1995, have been integrated into the National Immunization Programs, with infants receiving immunizations at birth, and after 1 and 5 mo[14,20]. Improvements in socioeconomic status and hospital hygiene have contributed to reducing HBV transmission rates[15].

Comprehensive vaccination programs have been crucial, emphasizing nationwide efforts to ensure universal vaccination coverage, particularly among newborns[16]. Furthermore, the adoption of single-use medical devices and improved hospital sanitation practices has helped mitigate the risks of HBV transmission. Establishing viral hepatitis surveillance systems has allowed monitoring of HBV prevalence over time and tracking the impact of vaccination programs[16].

Prenatal screening has been improved with universal screening of pregnant women, although challenges remain in ensuring coverage among all demographics[25]. Access to screening and testing for HBV infection, especially among high-risk populations, has been prioritized to identify and manage cases effectively[17]. Strengthening healthcare infrastructure, including access to screening, testing, and vaccination services, has been essential in improving HBV management[19].

Targeted vaccination programs have focused on high-risk groups, including healthcare workers, hemodialysis patients, and patients with thalassemia, to curb transmission[20]. Furthermore, the reinforcement of general preventive measures such as safe injection practices, proper sterilization of medical and dental equipment, and blood product screening has contributed to reducing the risks of HBV transmission[22].

Health education initiatives have played a crucial role in raising awareness of HBV transmission routes, preventive measures, and the importance of vaccination, leading to behavior changes and increased coverage of immunization[21,22]. However, challenges persist, including the need for continuous improvement in monitoring programs, data quality improvement, and staff training to ensure the effectiveness of HBV management strategies[26].

The study of HBV prevalence trends in Albania reveals a complex epidemiological landscape influenced by various public health interventions, socioeconomic factors, and migration patterns. Despite efforts to control HBV through vaccination programs and improved healthcare infrastructure, Albania remains a high-endemicity region with a prevalence exceeding 8%. This contrasts with neighboring countries like Greece and Italy, where HBV prevalence has significantly declined due to successful public health measures.

Greece, now classified as a low-endemicity country with a corrected prevalence of 1.88%, still shows substantial variability in HBV prevalence across different regions and among specific populations, such as immigrants. Notably, studies have indicated that Albanian immigrants in Greece exhibit higher HBV prevalence rates than the general Greek population, highlighting the ongoing impact of Albania's high endemicity on neighboring countries[27].

Similarly, Italy has experienced a dramatic decrease in HBV incidence following the implementation of a national universal vaccination program in 1991 and public health campaigns initiated in the 1980s. The incidence of acute hepatitis B in Italy has dropped from 98 cases per 100000 inhabitants in the 1960s to just 0.21 cases per 100000 inhabitants by 2020[28].

These reductions in HBV prevalence in Greece and Italy underscore the effectiveness of sustained public health efforts, particularly vaccination, in controlling HBV transmission. However, the persistent high prevalence in Albania, as well as among Albanian immigrants in Greece and Italy, suggests that the public health infrastructure in Albania requires further strengthening. Additionally, transnational public health strategies are needed to address the unique challenges posed by migration and to reduce the burden of HBV in the region. Overall, the comparison of HBV prevalence trends between Albania and its neighboring countries highlights the critical importance of robust vaccination programs, effective public health campaigns, and improved healthcare access in reducing HBV prevalence and achieving better public health outcomes.

During the period 1964-1990, the incidence of viral hepatitis in Albania exhibited a considerable elevation, fluctuating within the range of 200-400 cases per 100000 inhabitants. In recent years a noticeable dearth of comprehensive studies has been observed in the resident population of Albania on the incidence and prevalence of HBV. A notable deficiency in the diagnostic infrastructure for HBV is evident, with the majority of identified cases arising predominantly from voluntary individuals participating in blood donation or routine health examinations. The absence of a national surveillance system dedicated to monitoring HBV infection in Albania constitutes a significant impediment to accurate assessment and targeted management of this public health problem. The efficacy of anti-HBV vaccines has been potentially compromised over certain periods, contributing to the enduring high prevalence of HBV presently. A considerable proportion of people harboring HBV infections remain undiagnosed, exerting a substantial influence on the high prevalence of HBV that prevails in the Albanian population. There is a pressing imperative for in-depth investigations into the incidence and prevalence dynamics of HBV in Albania, underscoring the need for comprehensive and systematic research efforts. Despite the notable strides made through vaccination campaigns, the persistence of a substantial prevalence of HBV in Albania underscores the complexity of the issue, warranting continued efforts for a comprehensive understanding and effective mitigation.

| 1. | Tripathi N, Mousa OY. Hepatitis B. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2024. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Global Hepatitis B Vaccination. Why CDC is Working to Prevent Hepatitis B Globally. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/global-hepatitis-b-vaccination/why/index.html. |

| 3. | Committee on a National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Buckley GJ, Strom BL, editors. Eliminating the Public Health Problem of Hepatitis B and C in the United States: Phase One Report. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2016. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 689] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1794] [Cited by in RCA: 1778] [Article Influence: 98.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kwon SY, Lee CH. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection. Korean J Hepatol. 2011;17:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b#:~:text=For%20World%20Hepatitis%20Day%202023,the%202030%20hepatitis%20elimination%20target.. |

| 8. | Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:97-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1734] [Cited by in RCA: 1750] [Article Influence: 83.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin CL, Kao JH. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and variants. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5:a021436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hou J, Liu Z, Gu F. Epidemiology and Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Int J Med Sci. 2005;2:50-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Angoni R. Data on the prevalence of viral hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E infections in Albania. Buletini i Shkencave Mjekesore. 1998;70-3. |

| 12. | Troja P, Ndrenika Gj, Taka M, Pepa T. Acute A, B and non-A non-B virus hepatitis in children. Buletini i Shkencave Mjekesore. 1985;81-5. |

| 13. | Troja P. Antigen Australia in pregnant women, those who have just given birth, and in newborn children. Buletini i Shkencave Mjekesore. 1980;115-20. |

| 14. | Dalekos GN, Zervou E, Karabini F, Tsianos EV. Prevalence of viral markers among refugees from southern Albania: increased incidence of infection with hepatitis A, B and D viruses. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:553-558. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Malamitsi-Puchner A, Papacharitonos S, Sotos D, Tzala L, Psichogiou M, Hatzakis A, Evangelopoulou A, Michalas S. Prevalence study of different hepatitis markers among pregnant Albanian refugees in Greece. Eur J Epidemiol. 1996;12:297-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chironna M, Germinario C, Lopalco PL, Quarto M, Barbuti S. HBV, HCV and HDV infections in Albanian refugees in Southern Italy (Apulia region). Epidemiol Infect. 2000;125:163-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Katsanos KH, Christodoulou DK, Zervou E, Babameto A, Kraja B, Hyphantis H, Karetsos V, Tsonis G, Basho J, Resuli BF, Tsianos EV. Hepatitis B remains a major health priority in Western Balkans: results of a 4-year prospective Greek-Albanian collaborative study. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:698-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kondili LA, Ulqinaku D, Hajdini M, Basho M, Chionne P, Madonna E, Taliani G, Candido A, Dentico P, Bino S, Rapicetta M. Hepatitis B virus infection in health care workers in Albania: a country still highly endemic for HBV infection. Infection. 2007;35:94-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Elefsiniotis IS, Vezali E, Brokalaki H, Tsoumakas K. Hepatitis B markers and vaccination-induced protection rate among Albanian pregnant women in Greece. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5498-5499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Resuli B, Prifti S, Kraja B, Nurka T, Basho M, Sadiku E. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in Albania. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:849-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Milionis C. Serological markers of Hepatitis B and C among juvenile immigrants from Albania settled in Greece. Eur J Gen Pract. 2010;16:236-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Durro V, Qyra S. Trends in prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among Albanian blood donors, 1999-2009. Virol J. 2011;8:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zehender G, Ebranati E, Gabanelli E, Shkjezi R, Lai A, Sorrentino C, Lo Presti A, Basho M, Bruno R, Tanzi E, Bino S, Ciccozzi M, Galli M. Spatial and temporal dynamics of hepatitis B virus D genotype in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Roussos A, Goritsas C, Pappas T, Spanaki M, Papadaki P, Ferti A. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C markers among refugees in Athens. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:993-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Papaevangelou V, Hadjichristodoulou C, Cassimos D, Theodoridou M. Adherence to the screening program for HBV infection in pregnant women delivering in Greece. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kureta E, Basho M, Roshi E, Bino S, Simaku A, Burazeri1 G. Evaluation of the surveillance system for hepatitis B and C in Albania during 2013-2014. Albanian Med J. 2014;57-67. |

| 27. | Rigopoulou EI, Gatselis NK, Galanis K, Lygoura V, Gabeta S, Zachou K, Dalekos GN. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis B in Greece. Ann Gastroenterol. 2021;34:431-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sagnelli C, Sica A, Creta M, Calogero A, Ciccozzi M, Sagnelli E. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of hepatitis B virus infection in Italy over the last 50 years. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:3081-3091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |