Published online Sep 25, 2024. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v13.i3.96416

Revised: June 6, 2024

Accepted: July 18, 2024

Published online: September 25, 2024

Processing time: 114 Days and 20.6 Hours

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) continuum of care cascade illustrates the 90-90-90 goals defined by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (UNAIDS). The care cascade includes the following five steps: Diagnosis, linkage to care, retention in care, adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), and viral suppression.

To elaborate the HIV cascade of patients diagnosed with HIV at the Nossa Senhora da Conceição Hospital (HNSC) and to determine possible local causes for the loss of patients between each step of the cascade.

This retrospective cohort study included patients diagnosed with HIV infection from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2016 and followed up until July 31, 2019. The data were analyzed by IBM SPSS software version 25, and Poisson regression with simple robust variance was used to analyze variables in relation to each step of the cascade. Variables with P < 0.20 were included in multivariable analysis, and P < 0.05 was considered significant. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare the groups of patients followed up at the HNSC and those followed up at other sites.

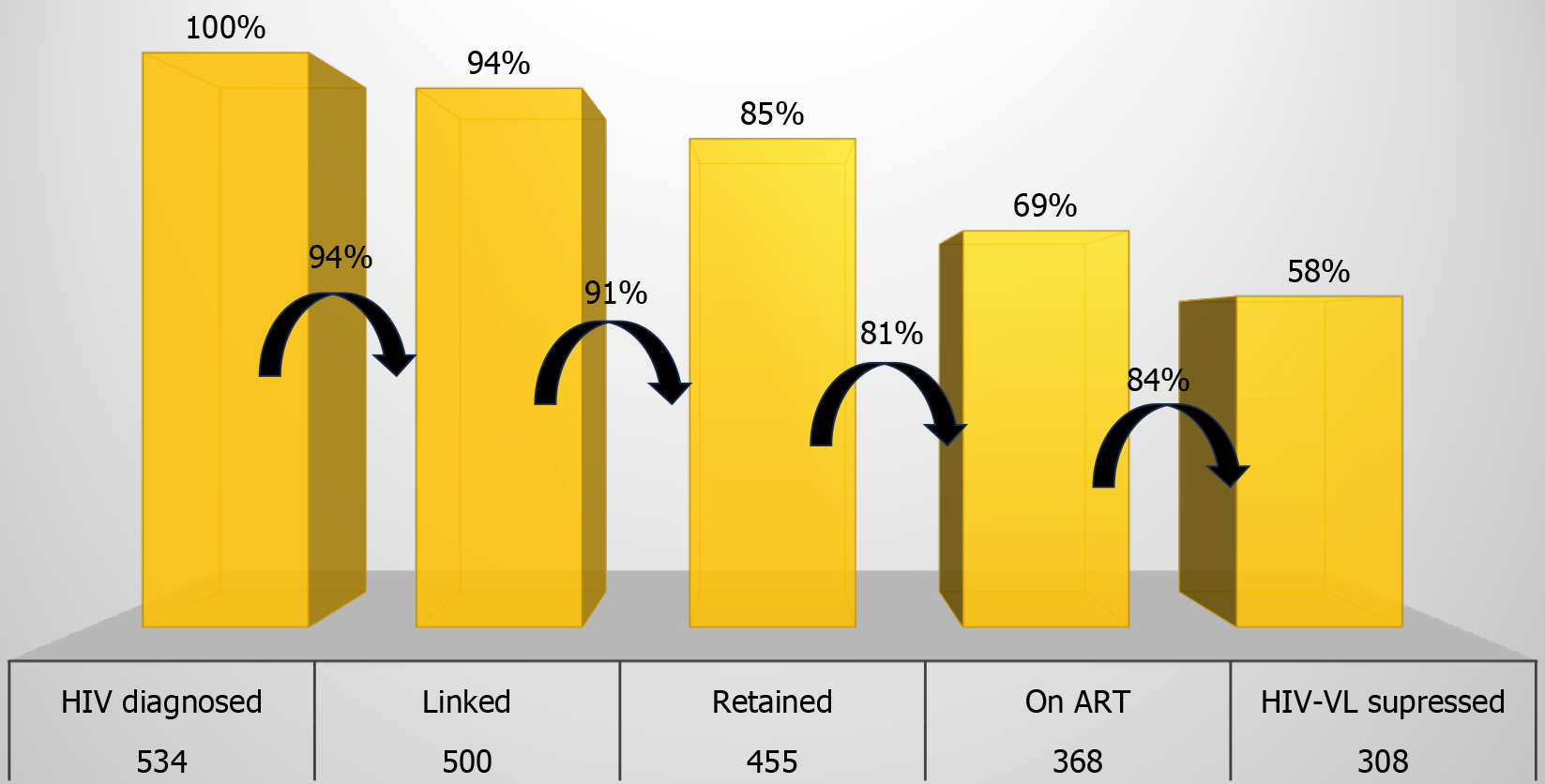

The results were lower than those expected by the UNAIDS, with 94% of patients linked, 91% retained, 81% adhering to ART, and 84% in viral suppression. Age and site of follow-up were the variables with the highest statistical significance. A comparison showed that the cascade of patients from the HNSC had superior results than outpatients, with a significant difference in the last step of the cascade.

The specialized and continued care provided at the HNSC was associated with better results and was closer to the goals set by the UNAIDS. The development of the HIV cascade using local data allowed for the stratification and evaluation of risk factors associated with the losses occurring between each step of the cascade.

Core Tip: The capital of southern Brazil, Porto Alegre, has the highest acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related mortality rate. These data demonstrate that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS is an important public health problem in the city, and it is important to carry out studies to improve indicators. The HIV cascade was adopted as a portrait of implemented public policies. That is why we decided to carry out this study with the objective of identifying the steps and results of continuity of care in patients diagnosed with HIV infection in a hospital located in Porto Alegre. The development of the HIV cascade using local data allowed for the stratification and assessment of risk factors associated with losses occurring between each stage of the cascade, to develop new strategies aimed at achieving the 90-90-90 target in future assessments.

- Citation: Vaucher MB, Fisch P, Kliemann DA. Human immunodeficiency virus cascade–continuum of care stages and outcomes in a hospital in southern Brazil. World J Virol 2024; 13(3): 96416

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v13/i3/96416.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v13.i3.96416

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has definitively changed the course of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, transforming it into a chronic disease, with a life expectancy similar to that of an adult without HIV infection[1,2]. In con

Brazil was one of the first countries in Latin America to adopt the goals set by the UNAIDS[7]. Estimates show that in 2021, approximately 960000 people were infected with HIV in Brazil; among all the individuals infected with HIV, 89% were aware of the diagnosis, 82% were linked to some health service, 76% retained their respective health services, 73% were on ART, and 65% had achieved HIV-VL suppression. These estimates were higher than those in previous years[7]. Unawareness of HIV infection, sexual behavior with low HIV risk perception, and low adherence to ART with HIV-VL recovery were the main causes of HIV infection in Brazil[8].

The Nossa Senhora da Conceição Hospital (HNSC) is a tertiary hospital located in Porto Alegre, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brazil, a city that ranked second in 2021 among the Brazilian capitals, with the highest AIDS detection rate[9]. In the same year, Porto Alegre also obtained the highest mortality rate, which was five-fold higher than the national rate and, the highest HIV detection rate in pregnant women, which was six-fold higher than the national rate[9]. The HNSC is a reference hospital for the care of PLHIV, with inpatient and outpatient lines of care for children, adolescents, adults, and pregnant women[10]. This study aimed to identify the characteristics of the patients diagnosed with HIV in the HNSC and recognize the continuum of care stages and outcomes in these patients through elaboration of the HIV cascade with local data. Thus, the HIV cascade was developed with local data to determine possible local causes for the loss of patients between each step of the cascade. As HNSC is a reference in public service in the region, the hypothesis is that the data would be very close to the UNAIDS target, despite the high mortality rate in the city.

This retrospective cohort study included patients diagnosed with HIV infection from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2016 and followed up until July 31, 2019. Patients aged 18 years or older, with a positive anti-HIV test (routine serology or screening), who were admitted or received outpatient care at the HNSC during the period of analysis, were included in the study. The exclusion criteria included the following: An HIV diagnosis before 2015 or after 2016 and missing data in the HNSC electronic medical records. Patients who died were included in the first analysis to identify the characteristics of the patients but were not considered in the cascade analysis. Data from the HNSC laboratory and HNSC electronic medical records were analyzed and linked with those from the Laboratory Test Control System and Medication Logistic Control System. Thereafter, a comparison was made between patients followed up after hospital discharge at the infectious disease outpatient clinic of the HNSC and at other sites (other cities or health institutions).

The requirements for each step of the cascade were subjectively defined based on the criteria of the Brazilian Ministry of Health. The first step included the number of people diagnosed with HIV infection in the period, always illustrated with the percentage of 100%. The second step included patients linked to some specialized service; after diagnosis, they underwent at least one CD4 + T-cell count or HIV-VL test. The third step of the cascade showed the number of users retained in the service, i.e., those who underwent at least two HIV-VL tests or two CD4 + T-cell counts, regardless of the period between them. The fourth step registered the number of patients on ART and who were still collecting their medications in 2019 (last analysis period). The fifth step included adherent patients to ART with an undetectable HIV-VL (< 50 copies/mL) at the last test. After analysis, five exposure columns were constructed to define the HIV cascade of all patients involved in the study who did not die. The percentages were calculated both in relation to the first and previous steps.

The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software version 25. Poisson regression with simple robust variance was used to estimate the incidence ratio (IR) at a 95%CI for each variable, including sex, age group, race, education, city of residence, and follow-up site, in relation to each step of the cascade: Linked, retained, on ART, and HIV-VL suppressed. All variables with P < 0.20 in simple analyses were included in the multivariable model. Adjustments were made only for the last two steps (on ART and undetectable HIV-VL), and only variables with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Two HIV cascades were also created, discriminating patients by follow-up location after HIV diagnosis at HNSC and hospital discharge. Each step of the HIV cascades of patients followed up at the HNSC and at other sites, as well as the sociodemographic characteristics of these groups of patients, were compared using the Pearson’s χ2 test, and results with P < 0.05 were considered significant. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Group and the requirement for informed consent was waived upon commitment to patient confidentiality.

The study included 629 patients diagnosed with HIV infection in 2015 and 2016. The profile of the participants by sociodemographic characteristics showed that 440 (70%) were white, 339 (54%) were women with a mean age of 40 years at diagnosis, 440 (70%) had completed elementary school, and 421 (67%) were from Porto Alegre. According to the medical records, 150 (24%) had comorbidities such as hypertension (12%), diabetes (4%), and asthma (3.5%), the most frequent illnesses among all the patients.

Moreover, around 471 (75%) of the patients had been hospitalized at least once in the HNSC after being diagnosed with HIV infection. The following causes of hospitalization are highlighted: HIV infection (22%), normal delivery or cesarean section (18%), and tuberculosis (11%). Opportunistic infections occurred in 164 (35%) of hospitalized patients, mostly tuberculosis (34%), toxoplasmosis (20%), pneumocystosis (14%), cytomegalovirus infection (12%), and cryptococcosis (12%). Another frequent AIDS-defining disease was lymphoma (6%). Of the patients diagnosed with opportunistic infections, 137 (84%) had a CD4 + T-cell count of < 200 cells/mm³.

Following an HIV diagnosis, 584 (93%) of patients underwent at least one CD4 + T-cell count and/or HIV-VL test. The time between diagnosis and the first CD4 + T-cell count was, for most patients, up to 30 days (75%); cumulatively, 94% had their samples collected within 6 months. Of the first CD4 + T-cell counts, 41% of patients had counts < 200 cells/mm³, 32% between 201 and 500 cells/mm³, and 27% > 500 cells/mm³. There were no differences in the first CD4 + T-cell collection between inpatients and outpatients. Moreover, 461 (79%) of the patients had undergone two or more CD4 + T-cell count tests, of whom 15% had a final CD4 + T-cell count of < 200 cells/mm³, 30% between 201 and 500 cells/mm³, and 55% of > 500 cells/mm³. Of the patients with a final CD4 + T-cell count of > 500 cells/mm³, 79% were ART adherent; however, of those who had a final CD4 + T-cell count of < 200 cells/mm³, only 37% were ART adherent.

ART medication was collected at least once by 534 (85%) of patients. The first ART prescription after an HIV diagnosis occurred within 30 days in 51% of cases, within 6 months in 86%, and within 1 year in 93%. The main regimen was tenofovir, lamivudine, and efavirenz (TDF/3TC/EFZ), corresponding to the treatment used in 62% of the patients; this was followed by tenofovir and lamivudine (TDF/3TC) + atazanavir and ritonavir (ATV/r), with 16% of the patients receiving this combination, and TDF/3TC + dolutegravir, with this being prescribed to only 5.2%. Approximately 120 patients had a history of pregnancy in the period and were treated with TDF/3TC/ATV/r (32%), TDF/3TC/EFZ (29%), and AZT/3TC + lopinavir and ritonavir (LPV/r) (26%). The analysis indicates that 69% of patients on ART did not switch regimens and 22% switched regimens only once. In addition, 95 patients (15%) died and were not included in further cascade analysis. Among these patients, the main cause of death was sepsis (42%), with 57% being diagnosed with opportunistic infections and 72% presenting a CD4 + T-cell count of < 200 cells/mm³.

Excluding deaths, 534 patients were selected for the cascade analysis, 500 (94%) were linked to the service, 455 (85%) were retained in care, 368 (69%) were on ART, and 308 (58%) achieved HIV-VL suppression (Figure 1). If the previous column was considered the denominator, the percentages would be as follows: 94% linked, 91% retained, 81% on ART, and 84% HIV-VL suppressed. Patient characteristics (sex, age, race and education, city of origin, and follow-up site) are listed in Table 1. Patients included in the cascade were predominantly women, white, aged 30–49 years, living in Porto Alegre, and with elementary school education. Of these, only 52% remained under follow-up at the HNSC.

| Total | Linked | P value | Retained | P value | On ART | P value | HIV-VL suppressed | P value | |

| Total | 534 | 500 (93.6) | 455 (85.2) | 368 (68.9) | 308 (57.6) | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 303 (56.7) | 284 (93.7) | 0.917 | 264 (87.1) | 0.161 | 198 (65.3) | 0.039 | 162 (53.5) | 0.023 |

| 1.00 (0.95-1.04) | 1.05 (0.97-1.13) | 0.88 (0.79-0.99) | 0.84 (0.73-0.97) | ||||||

| Male | 231 (43.3) | 216 (93.5) | 191 (82,7) | 170 (73,6) | 146 (63,2) | ||||

| 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Age (yr) | |||||||||

| 18-29 | 154 (28.8) | 148 (96.1) | 0.252 | 129 (83.8) | 0.420 | 92 (59.7) | 0.000 | 70 (45.5) | 0.000 |

| 1.03 (0.97-1.10) | 0.96 (0.86-1.06) | 0.73 (0.63-0.86) | 0.63 (0.51-0.78) | ||||||

| 30-49 | 270 (50.6) | 250 (92.6) | 0.964 | 230 (85.2) | 0.585 | 187 (69.3) | 0.012 | 159 (58.9) | 0.011 |

| 0.99 (0.93-1.06) | 0.97 (0.89-1.06) | 0.85 (0.75-0.96) | 0.82 (0.70-0.95) | ||||||

| > 50 | 110 (20.6) | 102 (92.7) | 96 (87.3) | 89 (80.9) | 79 (71.8) | ||||

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 374 (70.0) | 348 (93.0) | 319 (85.3) | 266 (71.1) | 255 (60.2) | ||||

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Not white | 160 (30.0) | 152 (95.0 ) | 0.367 | 136 (85.0) | 0.930 | 102 (63.7) | 0.108 | 83 (51.9) | 0.089 |

| 1.02 (0.97-1.06) | 0.99 (0.92-1.07) | 0.89 (0.78-1.02) | 0.86 (0.72-1.02) | ||||||

| Education | |||||||||

| Illiterate | 16 (3.0) | 12 (75) | 0.188 | 11 (68.8) | 0.103 | 9 (56.3) | 0.031 | 7 (43.8) | 0.064 |

| 0.80 (0.58-1.11) | 0.74 (0.51-1.06) | 0.60 (0.38-0.95) | 0.55 (0.30-1.03) | ||||||

| Elementary School | 367 (68.7) | 346 (94.3) | 0.840 | 310 (84.5) | 0.221 | 246 (67.0) | 0.000 | 202 (55.0) | 0.016 |

| 1.01 (0.87-1.17) | 0.91 (0.78-1.05) | 0.72 (0.61-0.84) | 0.70 (0.52-0.93) | ||||||

| High School | 136 (25.5) | 128 (94.1) | 0.861 | 120 (88.2) | 0.526 | 99 (72.8) | 0.007 | 87 (64.0) | 0.181 |

| 1.01 (0.87-1.17) | 0.95 (0.81-1.11) | 0.78 (0.65-0.93) | 0.81 (0.60-1.10) | ||||||

| University Education | 14 (2.6) | 13 (92.9) | 13 (92.9) | 13 (92.9) | 11 (78.6) | ||||

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| City of origin | |||||||||

| Porto Alegre | 370 (69.3) | 350 (94.6) | 312 (84.3) | 249 (67.3) | 210 (56.8) | ||||

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Metropolitan region | 128 (24.0) | 118 (92.2) | 0.367 | 112 (87.5) | 0.358 | 94 (73.4) | 0.175 | 79 (61.7) | 0.313 |

| 0.97(0.92-1.03) | 1.03 (0.95-1.12) | 1.09 (0.96-1.23) | 1.08 (0.92-1.28) | ||||||

| Countryside | 36 (6.7) | 32 (88.9) | 0.302 | 31 (86.1) | 0.766 | 25 (69.4) | 0.787 | 19 (52.8) | 0.658 |

| 0.94 (0.83-1.05) | 1.02 (0.88-1.17) | 1.03 (0.82-1.29) | 0.93 (0.67-1.28) | ||||||

| Follow-up site | |||||||||

| HNSC | 236 (51.8) | 236 (100) | 225 (95.3) | 197 (83.5) | 172 (72.9) | ||||

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| External | 220 (48.2) | 219 (99.5) | 0.317 | 209 (95.0) | 0.866 | 169 (76.8) | 0.07 | 135 (61.4) | 0.010 |

| 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 0.92 (0.83-1.00) | 0.84 (0.73-0.95) |

Only the variables education, in the linked step, and sex in the retained step, presented a P < 0.20; thus, they were included in the multivariable analysis. Regarding the column on ART in the univariate analyses, there was a significant difference (P < 0.20) for the variables sex, age group at diagnosis, education, race, place of residence, and follow-up site. Being a woman, not white, aged 18–30 and 31-49 years, not having complete higher education, and being followed up outside the HNSC were considered risk factors for non-adherence to ART. However, living in the metropolitan region was considered a protective factor for adherence to ART. In the multivariable analysis (Table 2), only the age groups 18–30 and 31–49 years were considered significant risk factors for non-adherence to ART (P < 0.05).

| On ART | P value | HIV-VL suppressed | P value | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 0.93 (0.85-1.02) | 0.163 | 0.90 (0.80-1.02) | 0.126 |

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age (yr) | ||||

| 18-29 | 0.79 (0.69-0.90) | 0.000 | 0.66 (0.54-0.80) | 0.000 |

| 30-49 | 0.90 (0.82-0.99) | 0.041 | 0.87 (0.76-0.99) | 0.044 |

| > 50 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Not White | 0.94 (0.85-1.05) | 0.325 | 0.91 (0.78-1.05) | 0.215 |

| Education | ||||

| Illiterate | 0.98 (0.75-1.28) | 0.886 | 1.03 (0.68-1.55) | 0.881 |

| Elementary School | 0.86 (0.73-1.00) | 0.060 | 0.86 (0.66-1.14) | 0.311 |

| High School | 0.93 (0.78-1.10) | 0.415 | 1.03 (0.78-1.37) | 0.794 |

| University Education | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| City of origin | ||||

| Porto Alegre | 0.96 (0.80-1.15) | 0.693 | ||

| Metropolitan region | 1.06 (0.88-1.27) | 0.534 | ||

| Countryside | 1.0 | |||

| Follow-up site | ||||

| HNSC | 1.09 (0.99-1.20) | 0.055 | 1.18 (1.03-1.34) | 0.011 |

| External | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Regarding the data in the last column, being aged 18–49 years, not having higher education, not being white, and not being followed up at the HNSC were considered risk factors for not achieving HIV-VL suppression (P < 0.20). In the multivariable analysis, follow-up at the HNSC was considered a protective factor for HIV-VL suppression (P < 0.05). Similarly, in adherence to ART, being aged 18–30 and 31-49 years alone was considered a risk factor for not presenting an undetectable HIV-VL (P < 0.05). It was not possible to analyze the use of drugs, consumption of alcohol, and smoking habits as variables of association with cascade steps due to lack of data in the medical records.

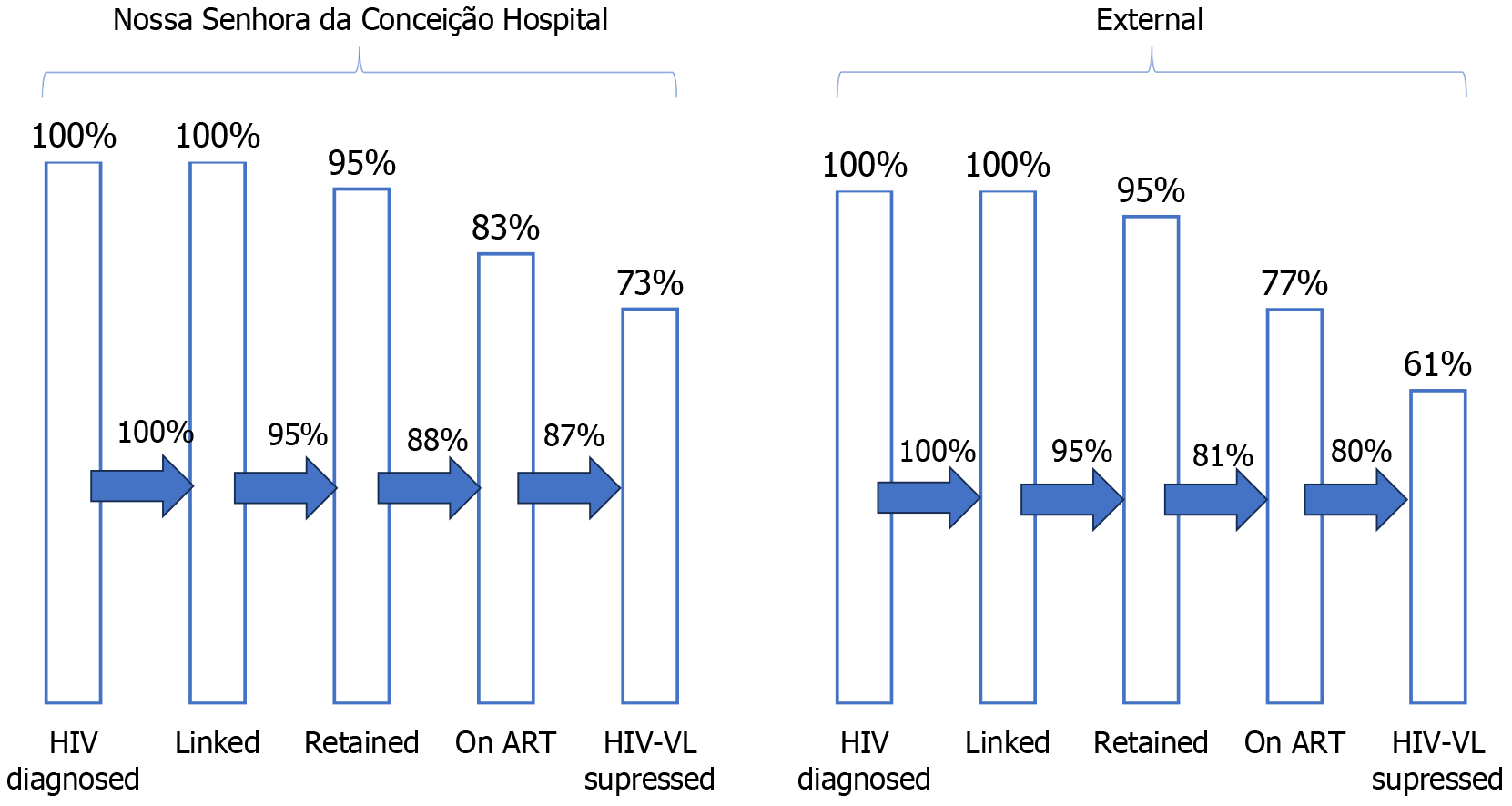

Of the 534 patients included in the HIV cascade, 78 had no outpatient appointments documented. In addition, 236 remained at the HNSC and 220 chose to have appointments at other sites. At the HNSC, 225 (95%) were retained, 197 (83%) adhered to ART, and 172 (73%) achieved HIV-VL suppression. Of the outpatients, 209 (95%) were retained, 169 (77%) adhered to ART, and 135 (61%) had an undetectable HIV-VL, as shown in Figure 2. The last column, comprising patients who achieved HIV-VL suppression, showed a significant difference, with P = 0.009.

The comparison between the characteristics of patients followed up at the HNSC and those followed up at other sites showed similar results with respect to sex, age group, race, education, and history of hospitalization (Table 3). There was also no difference between the groups regarding initial and final CD4 + T-cell counts, number of sample collections for CD4 + T-cell count and HIV-VL, and number of ART regimens. Only the city of residence and time of ART initiation after HIV diagnosis showed significant differences (P < 0.05) between the groups.

| HNSC | External | P value | |

| Total | 236 | 220 | |

| Gender | 0.217 | ||

| Female | 127 (53.8) | 131 (59.5) | |

| Age (yr) | 0.057 | ||

| 18-29 | 70 (29.7) | 60 (27.3) | |

| 30-49 | 107 (45.3) | 122 (55.5) | |

| > 50 | 59 (25.0) | 38 (17.3) | |

| Race | 0.945 | ||

| White | 167 (70.8) | 155 (70.5) | |

| Education | 0.485 | ||

| Illiterate | 4 (1.7) | 5 (2.3) | |

| Elementary School | 161 (68.2) | 150 (68.5) | |

| High School | 61 (25.8) | 60 (27.4) | |

| University Education | 10 (4.2) | 4 (1.8) | |

| City of origin | 0.000 | ||

| Porto Alegre | 189 (80.1) | 127 (57.7) | |

| Metropolitan region | 36 (15.3) | 73 (33.2) | |

| Countryside | 11 (4.7) | 20 (9.1) | |

| Hospital admission | 160 (67.8) | 161 (73.2) | 0.208 |

| Initial CD4+ T-cell count | 0.075 | ||

| 0-200 cells/mm3 | 91 (38.6) | 71 (32.4) | |

| 201-500 cells/mm3 | 84 (35.6) | 70 (32.0) | |

| > 501 cells/mm3 | 61 (25.8) | 78 (35.6) | |

| Final CD4+ T-cell count | 0.518 | ||

| 0-200 cells/mm3 | 17 (7.6) | 20 (9.6) | |

| 201-500 cells/mm3 | 76 (33.8) | 61 (29.3) | |

| > 501 cells/mm3 | 132 (58.7) | 127 (61.1) | |

| Number of CD4+ T-cell /HIV-VL samples | 0.316 | ||

| 1-3 | 53 (22.6) | 55 (25.2) | |

| 4-6 | 103 (43.8) | 104 (47.7) | |

| 7 or more | 79 (33.6) | 59 (27.1) | |

| Number of ART schemes | 0.215 | ||

| 1 | 164 (69.5) | 142 (64.5) | |

| 2 | 44 (18.6) | 56 (25.5) | |

| > 3 | 24 (10.2) | 21 (9.5) | |

| Time of ART initiation | 0.001 | ||

| Up to 1 month | 117 (50.4) | 103 (47.0) | |

| 1-6 months | 94 (40.5) | 67 (30.6) | |

| 6-12 months | 12 (5.2) | 24 (11.0) | |

| After 1 year | 9 (3.9) | 25 (11.4) |

Of the patients followed up at the HNSC, 66.2% had their first appointment within 6 months and 81.3% within 1 year. After diagnosis, 42% of patients had two to four appointments in the period analyzed and 43% had five to eight, equivalent to an average of two appointments per year, as indicated by the Ministry of Health. According to these recommendations, 50% of the patients who achieved HIV-VL suppression had five to eight appointments. Similarly, 70% of the patients who achieved no HIV-VL suppression had fewer than five appointments.

The first step in the HIV continuum of care cascade is diagnosis, and the major challenge is to make this diagnosis at the beginning of the infection[11]. In this study, the number of patients who had HIV infection and were unaware of it was not calculated, which is the first column defined by the UNAIDS. Early diagnosis implies reduced morbidity, mortality, costs, and transmission by individuals with unknown serological status, which influences all subsequent steps in the HIV continuum of care cascade[12,13]. To avoid this, it would be essential to increase access to anti-HIV testing, based on national recommendations and local epidemiology[12,13]. The HNSC has implemented a flow of serological tests for infectious diseases at admission, and many of the HIV diagnoses are made in patients seeking care for symptoms unrelated to the disease. This can be verified in the causes for hospital admission, with almost 80% of cases not being related to HIV infection.

The characteristics of the patients who participated in this study differed from the epidemiological data from Brazil and RS regarding the predominance of women, possibly because women more frequently seek care from health services. The dominant age range in this study was 30–49 years, corroborating the age range in the RS (35–39 years) and Brazil (25–39 years)[14,15]. However, there was a difference in this study’s data, which showed a predominance of white people, and the national data (which showed a predominance of black people). This is justified because most of the population in RS is white due to European colonization[14,15]. The HNSC is a hospital that provides 100% care through the Unified Health System, with a higher prevalence of patients with lower purchasing power and low educational level. State and national data also report that most patients have a low educational level[14,15]. It was not possible to compare the infection rate between heterosexual or homosexual individuals due to lack of data in the medical records.

A late diagnosis is defined by an HIV diagnosis with a first CD4 + T-cell count of < 200 cells/mm³, which indicates late presentation to the health system and failure to access a diagnosis[12,16]. Although most patients had this test when their counts were > 200 cells/mm3 at diagnosis, 41% were diagnosed late, with their initial CD4 + T-cell count < 200 cells/mm3. CD4 + T-cell counts < 200 cells/mm³ were indicative not only of opportunistic infections but also death. There is a trend in RS and in Brazil toward a reduced late diagnosis rate, and this may be one of the contributions to a reduced coefficient of mortality by HIV/AIDS[14,15]. In the state of RS, only 23% of people diagnosed with HIV infection had a CD4 + T-cell count of < 200 cells/mm³ in 2016[15]. In Brazil, since 2015, only 27% of people diagnosed with HIV presented with a CD4 + T-cell count < 200 cells/mm³, with a median first count of 387 cells/mm³ in 2018. A late diagnosis was related to being a man, aged > 40 years, being black, and with a low educational level (corresponding to both national and the current study’s data)[16].

The analysis of the linked and retained patients considered the collection of one and two samples of CD4 + T-cell counts/HIV-VL tests, respectively, and these pillars of the cascades presented the greatest disparity in the criteria among the reviewed studies[16]. The collection of these tests refers to the performance of specialized medical care and possibly to the link to health services. In this study, the percentages related to linkage and retention to care were consistent with the UNAIDS expectations, both for the overall cascade and cascades of patients followed up at the HNSC and those followed up at other sites. The short period of time between diagnosis and the first CD4 + T-cell count can be explained mainly by the hospital protocol to request a CD4 + T-cell count/HIV-VL test immediately after positive serology results.

Of the patients diagnosed with HIV infection, 15% had no appointments at any site and 7% underwent no CD4 + T-cell count/HIV-VL test. This difference can be explained by the sample collection during hospitalization. Some of the reasons for non-linkage and non-retention to care are stigma, fear, denial, mental health problems, lack of transportation, and health system bureaucracies[17]. The stimulus for retention in care can be provided by health professionals, with more information being provided about appointments and necessary care, social assistance and transportation, and adjusted date and frequency of appointments according to the patient’s availability, in addition to providing care with cordiality and efficiency in a welcoming environment[17].

Early initiation and adherence to ART are beneficial and essential for improving the immune pattern, reducing viral replication and transmission[12,13,18]. National data indicate that ART use is recommended for all people with HIV infection, regardless of the CD4 + T-cell count, provided the early use of ART[16]. In 2018, approximately 78% of the patients diagnosed with HIV infection in Brazil initiated ART within 6 months of the first CD4 + T-cell count[9]. In 2015 and 2016, 65% and 77% of the patients, respectively, diagnosed with HIV infection in Brazil initiated ART within 6 months of the first CD4 + T-cell count collection (these percentages were lower than those reported in this study)[16].

This study shows that 85% of patients receive ART at least once after an HIV diagnosis, corroborating the trend in RS, which has progressively invested in actions to combat the epidemic[15,16]. Compared with external patients, the early prescription of ART for patients followed up at the HNSC can be explained either by the prescription of ART during hospitalization or by the early return to the HNSC infectious diseases outpatient clinic. This study identified that 37.5% of patients who did not initiate ART during the study period died. Sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors, including a patient’s perception of health, stigma, fear, weak social support, and difficulty in accessing health services, may be associated with patients who never initiated ART[19]. Some of the measures to reduce the barriers between diagnosis and ART initiation are simpler regimens with fewer pills, reducing the frequency of pill collection with lower costs, and spreading the idea that new medications have minimal adverse effects and that initiating medication use before feeling sick is more beneficial[19]. The single tablet regimen (TDF/3TC/EFZ) was defined by the Brazilian protocol as being preferential from 2013 to 2016. Only in 2017, the integrase inhibitor regimen (dolutegravir) became a priority for ART treatment naive patients and for regimen switch in HIV-VL suppressed patients[12].

The main gap identified in the overall cascade occurred between retention to care and adherence to ART. Similar to what was reported in national reports, being a man, being white, a higher educational level, and older age showed a tendency toward greater adherence to ART[16]. In this study, being aged 18–49 years was considered the greatest obstacle to adherence, and was established as a criterion for the group that needs greater intervention. A place of residence in the metropolitan region can increase adherence due to the increased number of places with pharmacies providing ART. New policies with greater decentralization of specialized care could improve care for patients who live in the interior.

Patients followed up at the HNSC did not reach the UNAIDS goals for ART adherence, despite reaching a value close to 90% (88%). The early initiation of ART observed in this study may have positively influenced adherence, although there is still a need to encourage maintenance of adherence and to develop new measures to improve ART distribution and access[20].

Adherence to ART is essential for achieving HIV-VL suppression, except in elite control patients[21]. The sociodemographic risk factors for persistence of detectable HIV-VL despite ART use in Brazil are the same as those cited above for non-adherence to ART[16]. In this study, being aged 18–49 years was considered the main risk factor for the non-occurrence of HIV-VL suppression, which may be related to the low perception of risk and health care by young people. Persistent viremia can be explained mainly by poor adherence or failure to institute ART, as well as the use of less potent ART drugs than the new integrase inhibitors.

Only 84% of patients who adhered to ART achieved HIV-VL suppression. Of the patients in the HNSC and outpatient subgroups, 87% and 80% of adherent patients achieved HIV-VL suppression, respectively. The better results of patients who were followed up at the HNSC can be explained by maintenance of the link and care provided by infectious diseases physicians. Appointments with specialists who prioritize guidelines, with appropriate ART prescription and regime switches and with the provision of genotyping, when necessary, enhance patient care[22]. It was not possible to assess whether the care in external places was with a specialist physician or if the patients were seen in the same place with adequate frequency, as the only information obtained was the place of collection of the medication.

Better HIV-VL suppression results at the HNSC could be achieved mainly by increasing the number of appointments, since less than half of the patients had the two annual appointments recommended by the guidelines[12]. Prioritizing more immunosuppressed patients (CD4 + T-cell count < 200 cells/mm³) and those at higher risk of dropping out of treatment, such as younger patients, would improve ART adherence interventions to achieve HIV-VL suppression. Thus, not only HIV-VL suppression should be considered but also its impact on the daily lives of patients, as they depend on several psychosocial, sociodemographic, and socioeconomic aspects[23]. HIV-VL suppression needs to be reproduced from the perspective of the dynamics of patients’ lives, analyzing not only operational factors but also their contexts for the implementation of effective measures[23]. The main limitations of this study are related to the data missing from the medical records of the HNSC and of other sites, which were important for a thorough analysis of the sociodemographic variables.

The continuous follow-up of patients with the development of the HIV cascade with local data allows for the identification of the local HIV epidemic status. In this study, the HIV cascade of the HNSC identified the sociodemographic characteristics and subsequent health care outcomes of patients diagnosed with HIV infection in the HNSC. It was also possible to stratify and to evaluate risk factors associated with cascade leakages, such as age group, for the development of strategies directed at the 90-90-90 goal. The difference in the results obtained from the place of follow-up after diagnosis and those from the HNSC showed the importance of specialized and continued care, to obtain outcomes close to the goals set by the UNAIDS. New studies are needed for the continuous evaluation of indicators related to HIV care.

We would like to thank the HNSC for supporting this work and especially the immunology staff of the HNSC laboratory who respectfully received the data collectors.

| 1. | MacCarthy S, Hoffmann M, Ferguson L, Nunn A, Irvin R, Bangsberg D, Gruskin S, Dourado I. The HIV care cascade: models, measures and moving forward. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:19395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bhaskaran K, Hamouda O, Sannes M, Boufassa F, Johnson AM, Lambert PC, Porter K; CASCADE Collaboration. Changes in the risk of death after HIV seroconversion compared with mortality in the general population. JAMA. 2008;300:51-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | UNAIDS. On the fast track to end AIDS. 2015. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20151027_UNAIDS_PCB37_15_18_EN_rev1.pdf. |

| 4. | UNAIDS. 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2017. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf. |

| 5. | Kay ES, Batey DS, Mugavero MJ. The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum: updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Medland NA, McMahon JH, Chow EP, Elliott JH, Hoy JF, Fairley CK. The HIV care cascade: a systematic review of data sources, methodology and comparability. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:20634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brazil. Relatório de Monitoramento Clínico do HIV 2021. Available from: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/relatorio_monitoramento_clinico_hiv_2021.pdf. |

| 8. | Mangal TD, Pascom ARP, Vesga JF, Meireles MV, Benzaken AS, Hallett TB. Estimating HIV incidence from surveillance data indicates a second wave of infections in Brazil. Epidemics. 2019;27:77-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brazil. Boletim Epidemiológico - HIV/Aids 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/central-de-conteudo/boletins-epidemiologicos/2022/hiv-aids/boletim_hiv_aids_-2022_internet_31-01-23.pdf/view. |

| 10. | GHC. Grupo Hospitalar Conceição (GHC), 2017. Letter of Services to the Citizen. Available from: https://ghc.com.br/default.asp?idMenu=cartacidadao&idSubMenu=14. |

| 11. | Brazil. Manual técnico para o desenvolvimento de uma cascata de cuidados Continuados no domínio da HIV. Available from: https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/central-de-conteudo/publicacoes/2017/manual_tecnico_cascata_final_web.pdf. |

| 12. | Brasília. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Manejo da Infecção pelo HIV em Adultos. Available from: https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/central-de-conteudo/pcdts/2013/hiv-aids/pcdt_manejo_adulto_12_2018_web.pdf/view. |

| 13. | Darling KE, Hachfeld A, Cavassini M, Kirk O, Furrer H, Wandeler G. Late presentation to HIV care despite good access to health services: current epidemiological trends and how to do better. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146:w14348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brazil. Boletim Epidemiológico Especial - HIV/AIDS 2019. Available from: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/especiais/2019/boletim-epidemiologico-especial-hiv-aids-2019/view. |

| 15. | Rio Grande do Sul. Secretary of State for Health. State STD/AIDS Control Section. Epidemiological Bulletin: HIV/AIDS. Available from: https://saude.rs.gov.br/upload/arquivos/201910/30120845-boletim-epidemiologico-hiv-aids-rs-2018-versao-online-final.pdf/. |

| 16. | Brazil. Ministry of Health. Secretariat of Health Surveillance, Department of Chronic Diseases and Sexually Transmitted Infections (DCCI). Available from: https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/central-de-conteudo/publicacoes/2019/relatorio-de-monitoramento-clinico-do-hiv-2019. |

| 17. | Giordano TP. The HIV treatment cascade--a new tool in HIV prevention. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:596-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhao Y, McGoogan JM, Wu Z. The Benefits of Immediate ART. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2019;18:2325958219831714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ahmed S, Autrey J, Katz IT, Fox MP, Rosen S, Onoya D, Bärnighausen T, Mayer KH, Bor J. Why do people living with HIV not initiate treatment? A systematic review of qualitative evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2018;213:72-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bulstra CA, Hontelez JA, Ogbuoji O, Bärnighausen T. Which delivery model innovations can support sustainable HIV treatment? Afr J AIDS Res. 2019;18:315-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gonzalo-Gil E, Ikediobi U, Sutton RE. Mechanisms of Virologic Control and Clinical Characteristics of HIV+ Elite/Viremic Controllers. Yale J Biol Med. 2017;90:245-259. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Labhardt ND, Ringera I, Lejone TI, Cheleboi M, Wagner S, Muhairwe J, Klimkait T. When patients fail UNAIDS' last 90 - the "failure cascade" beyond 90-90-90 in rural Lesotho, Southern Africa: a prospective cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20:21803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Seckinelgin H. HIV care cascade and sustainable wellbeing of people living with HIV in context. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22:e25259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |