Published online Sep 25, 2021. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v10.i5.256

Peer-review started: March 23, 2021

First decision: May 5, 2021

Revised: May 17, 2021

Accepted: July 26, 2021

Article in press: July 26, 2021

Published online: September 25, 2021

Processing time: 176 Days and 21 Hours

Influenza viruses and coronaviruses have linear single-stranded RNA genomes with negative and positive sense polarities and genes encoded in viral genomes are expressed in these viruses as positive and negative genes, respectively. Here we consider a novel gene identified in viral genomes in opposite direction, as positive in influenza and negative in coronaviruses, suggesting an ambisense genome strategy for both virus families. Noteworthy, the identified novel genes colocolized in the same RNA regions of viral genomes, where the previously known opposite genes are encoded, a so-called ambisense stacking architecture of genes in virus genome. It seems likely, that ambisense gene stacking in influenza and coronavirus families significantly increases genetic potential and virus diversity to extend virus-host adaptation pathways in nature. These data imply that ambisense viruses may have a multivirion mechanism, like "a dark side of the Moon", allowing production of the heterogeneous population of virions expressed through positive and negative sense genome strategies.

Core Tip: A novel genes identified in viral genomes in opposite direction, as positive in influenza and negative in coronaviruses, are considered. The identified novel genes colocolized in the same RNA regions of viral genomes, where the previously known opposite genes are encoded, a so-called ambisense stacking architecture of genes in virus genome. It seems likely, that ambisense gene stacking in influenza and coronavirus families significantly increases genetic potential and virus diversity to extend virus-host adaptation pathways in nature. These data imply that ambisense viruses may have a multivirion mechanism, like "a dark side of the Moon", allowing production of the heterogeneous population of virions expressed through positive and negative sense genome strategies.

- Citation: Zhirnov O. Ambisense polarity of genome RNA of orthomyxoviruses and coronaviruses. World J Virol 2021; 10(5): 256-263

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v10/i5/256.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v10.i5.256

Orthomyxo- and coronaviruses are two families of enveloped viruses containing single stranded linear RNA genomes. Orthomyxovirus family includes seven genera: Alphainfluenzavirus, Betainfluenzavirus, Deltainfluenzavirus, Gammainfluenzavirus, Isavirus, Thogotovirus, and Quaranjavirus. These viruses infect wide range of hosts including mammals, birds, rodents, fish, ticks and mosquitoes. Orthomyxoviridae viruses contain six to eight segments of negative-sense single stranded RNA with a total genome length of 10-15 Kb[1]. Coronaviridae is divided into the four genera: Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus. Alpha- and betacoronaviruses infect mammals, while gamma- and deltacoronaviruses primarily infect birds. The size of genomic positive sense RNA of coronaviruses ranges from 26 to 32 kilobases, one of the largest genome among RNA viruses[2]. Here we mainly consider alphainfluenza viruses and betacoronaviruses as a typical members in both families.

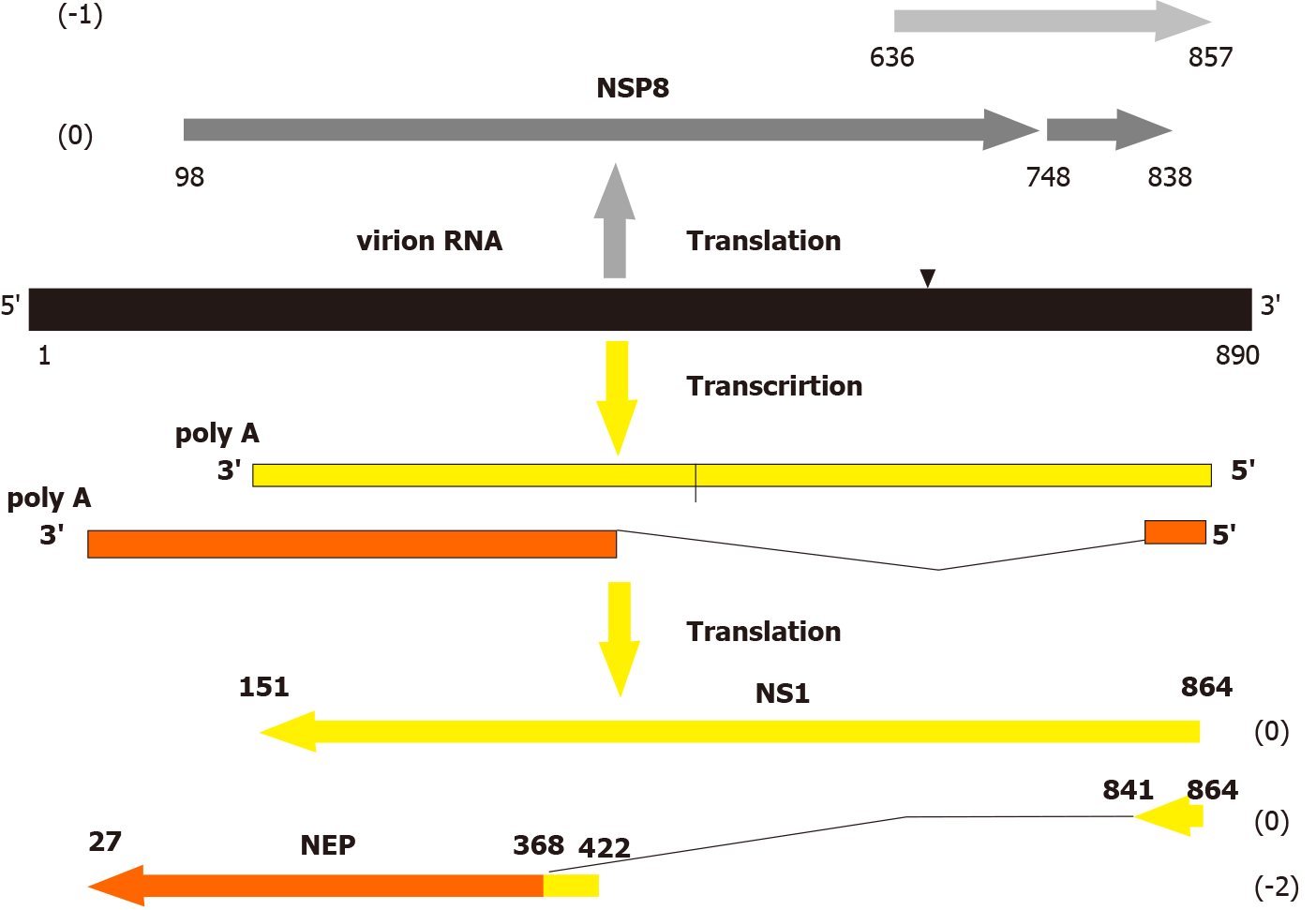

Genome of influenza A viruses is composed of 8 segments of single-stranded RNAs with mol. wt. 0.7-2.8 × 103 kilobases/segment. Each segment encodes one or several unique polypeptides through the canonical negative sense genome strategy (Table 1). It means that genome RNA of negative sense polarity is transcribed by the virus polymerase to produce positive sense mRNAs, which recognized by ribosomes to translate individual viral proteins (Figure 1). In addition to the negative sense genes, influenza A virus genome segments were found to contain long open reading frames (ORFs, genes) in opposite positive sense orientation. These ORFs have all ribosome translation elements: canonical start codon AUG or noncanonical CUG, termination codons (UAG, UAA, or UGA), internal ribosome entry sites (IRES), and Kozak-like sequences at the initial start codon[3-9].

| Viral RNA segments and their length (nt)1 | Positive sense polypeptides (mol. wt., kDa)2 | Negative stranded polypeptides, NSPs (mol. wt.; a.a.)3 |

| PB1 (2341) | PB1 (86.6); PB1-N40 (89.4); PB1-F2 (10.5) | NSP1 (174, 239) |

| PB2 (2341) | PB2 (85.7); PB2-S1 (55) | NSP2 (116, 121, 130, 137) |

| PA (2223) | PA (84.2); PA-X (29); PA-N155 (62); PA-N182 (60) | NSP3 (95, 109) |

| HA (1778) | HA (61.5) | NSP4 (n.d.) |

| NP (1565) | NP (56.1); eNP (56.8) | NSP5 (117, 154) |

| NA (1413) | NA (50.1); NA43 (48.6) | NSP6 (91, 154) |

| M (1097) | M1 (27.8); M2 (11); M42 (13) | NSP7 (99, 102, 109) |

| NS (890) | NS1 (26.8); NEP (14.2); NS3 (21); tNS1 (17) | NSP8 (93, 167, 216) |

There are three groups of data showing in vivo expression potential of these negative stranded genes. (1) The template function of the full length “negative sense” genome RNA of segment 8 (NS) was demonstrated in a cell-free translation system of rabbit reticulocyte lysate. It was shown that influenza A virion RNA of segment 8 can initiate synthesis of major polypeptide negative stranded protein (NSP8) (mol.wt. 23 kD) specifically reacted with antibody to the central domain of the NSP8[10]; (2) The NSP8 encoded in the 8’th influenza A virus segment NS could be expressed in vivo, in insect cells (ovary cell line of Trichplusia ni) infected with recombinant baculovirus (insect nuclear polyhedrosis virus) carrying influenza virus sequence NSG8 in the virus DNA genome. This gene appeared to express ~20 kD influenza-specific polypeptide NSP8, which was intracellularly stable and accumulated in the perinuclear zone of infected cells[11]. Later, it was also supported that influenza A virus NSP8 could be efficiently expressed from either a plasmid or a recombinant vaccinia virus in mammalian cells and the synthetized NSP8 was localized in the perinuclear endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and post-ER cellular compartments[12]; and (3) There are data that mice infected with influenza virus produce CTL response specific to epitopes presented in the influenza NSP8 protein[12-14]. These findings also demonstrate that translation of sequences locating on the negative RNA strand of a single-stranded RNA genome of influenza A virus can develop in vivo and can initiate antiviral CTL response and immunosurveillance.

The mature product of the NSP8 gene has not been yet identified in biological systems such virus-infected cells and animals. The failure to detect NEG8 protein could be due to a number of factors other than the complete absence of translation from genomic RNA. The properties of the NSP8 as an “escaping protein” may be explained either by its low synthesis and a short period of life or/and strong tissue-specific expression in certain cell types containing factors which are necessary for the regulation of expression of these “negative sense” genes. It would not be surprising if negative polarity genes are only expressed physiologically under special circumstances in vivo determining host cell tropism of influenza viruses.

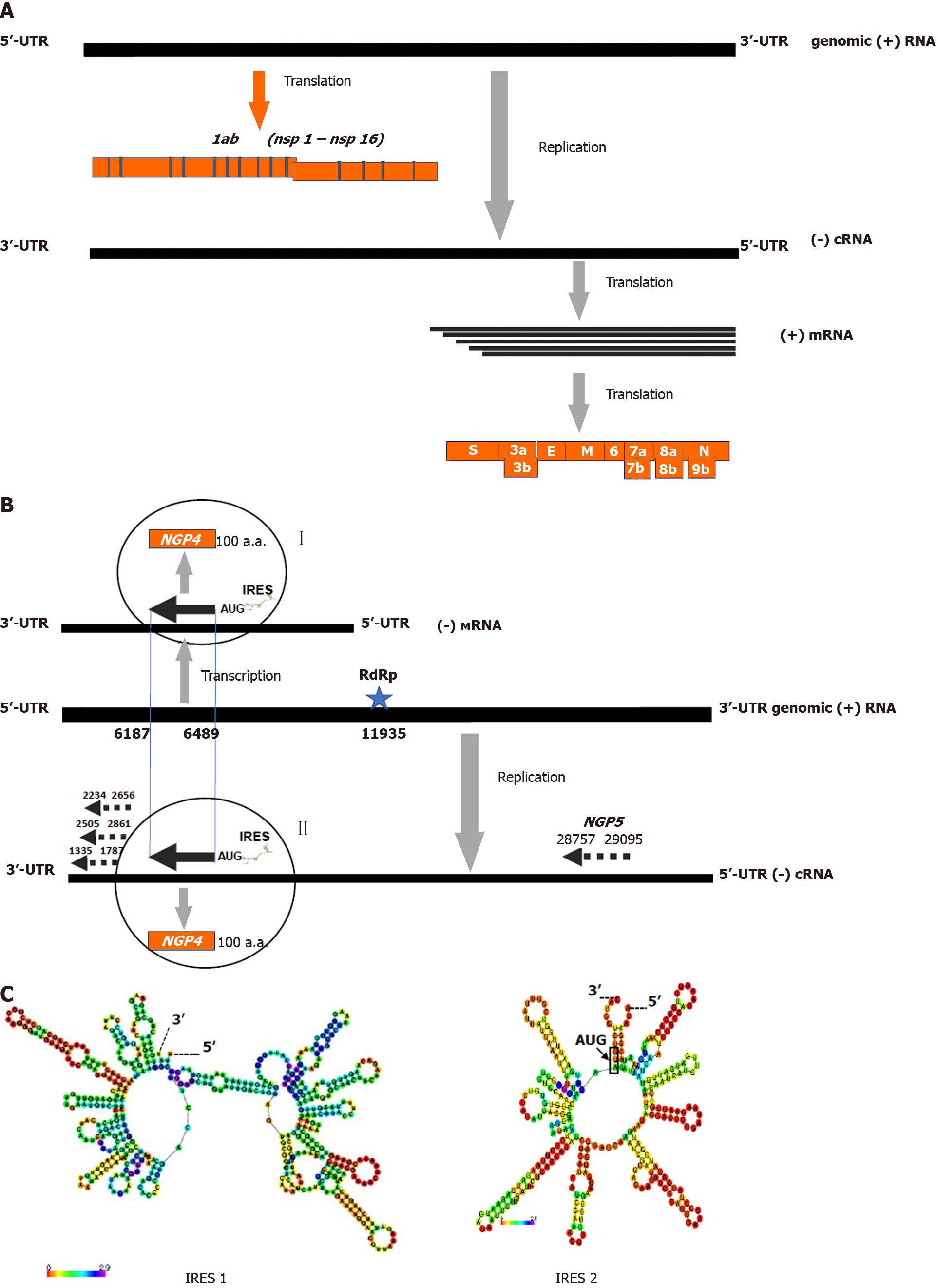

Recently, similar ambisense polarity has been revealed in coronaviruses genomes[15]. It is well known that these viruses possesses a linear positive sense genome RNA of 25-29 × 103 kb length[2]. The coronavirus genome RNA contains two groups of genes expressing proteins through the positive sense strategy. The first ones (nonstructural genes for nsp1-nsp19 proteins) are localized at the 5’-region of the virion genome RNA and directly translated by host ribosomes. The second ones (mostly the structural proteins genes N, S, HE, M, E and several accessorial proteins, such as 3a/b, 6, 7a/b, 8a/b, 9b, etc.) occupy a 3’-region of the virion RNA and express proteins through the translation of subgenomic mRNAs, which was transcribed on the anti-genomic RNA template[16] (Figure 2A). In addition to the positive sense genes, we have identified numerous long open reading frames in negative sense orientation (Table 2; Figure 2B). Like in the case of the ambisense genes of flu viruses, coronavirus negative sense genes have all elements characteristic of the mRNA molecules which are recognized by host ribosomes: classical AUG or alternative CUG[17] start codons, termination codons, IRES, and Kozak-like sequences at the start area[18,19]. However, unlike to influenza A viruses, coronavirus ambisense polarity has opposite configuration: a positive sense genome strategy and a negative sense orientation of the novel negative sense genes, so called a negative sense genes or negative gene proteins (NGPs).

| Virus genera | Viral genomes | Number of NSGs in virus genome1,3 | M.W. range of the NGPs2 |

| Alpha-coronaviruses | HCov-229E: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_002645.1 | 29/1/29/5 | 12.4-14.4 |

| Beta-coronaviruses | SARS-CoV-1: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_004718.3 | 34/0/35/2 | 11.5- 15.0 |

| SARS-CoV-2: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MT635445.1 | 21/1/26/4 | 10.9- 17.2 | |

| MERS: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_019843.3 | 32/8/23/3 | 11.1- 18.6 | |

| Pangolin-CoV: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MT040335.1 | 29/3/17/4 | 10.8-19.9 | |

| HCov-HKU1: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_006577.2 | 15/1/13/2 | 11.5- 15.0 | |

| Bat coronavirus RATG13: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MN996532.1 | 17/2/29/1 | 10.9- 19.7 | |

| Bovine coronavirus BCoV-ENT: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_003045.1 | 25/1/26/0 | 20.8 | |

| Murine hepatitis virus A59: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/FJ884687.1 | 29/5/42/7 | 11.2-36.8 | |

| Gamma-coronaviruses | Avian infectious bronchitis virus: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_001451.1 | 20/6/8/3 | 12.7- 26.5 |

| Delta-coronaviruses | Porcine coronavirus HKU15: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_039208.1 | 26/5/29/3 | 11.2- 17.4 |

The identification of coronavirus negative-polarity genes implies two possible mechanisms of their expression and synthesis of the corresponding mRNAs and proteins. These mechanisms include either direct translation of a replicative (-)copy of genomic (+)RNA (replication pathway II) or the transcription of genomic (+)RNA by viral polymerase with the formation of subgenomic mRNAs of “negative polarity” for their subsequent translation to synthesize specific viral polypeptides (transcription pathway I). To realize pathway I coronavirus genome contains poly A sequence (positions 11935-1194 nt) functioning as a viral polymerase binding site and transcrip

The function and role of the newly discovered ambipolar viral genes have not yet been determined. In the case of influenza viruses, there are indirect data that the identified new ambisense genes can be involved in the regulation of the host immune response against viral proteins and/or in the regulation of the stability of viral proteins in infected cells through the protein deubiquitinating system[5,12]. The possible functional significance of the novel ambisense genes is not yet generally clear. However, the stability and retaining of these type of genes in field viruses genomes for more than 100 years at the high variability of virus population suggest the functional necessity of these genes and their biological evolutionary determination[20]. Notably, the influenza NSP8 has high synonymous/nonsynonymous (dN/dS) mutations rate (> 1.5), which was similar to that one for the most variable surface virus glycoproteins HA and NA representing major target for antiviral host adaptive immune response. The elevated variability of the NSP8 implies that it undergoes positive selection and host adaptation, which influence its evolution[5].

The discovery of new ambisense genes has raised a number of important questions regarding its origin, functions, and evolutionary variability. One of the essential questions is how the novel genes have emerged in the genomic region to encode two opposite sense genes. The appearance of the ambipolar gene suggests the existence of yet unknown correspondence principle (or reverse determination rule) for the expression of oppositely directing genes locating in the same region of RNA molecule. This principle implies that a certain pre-existing gene can predetermine the emergence mechanism and the properties of a new ambipolar gene[5]. Without this rule, chaotic accumulation of mutations will result in the appearance of a new functional gene and its further evolutionary selection, that seems to be unlikely. Moreover, the probability for such chaotic event is low, considering the ambipolar overlapping of several preexisting genes, when changes in one of them would cause changes in the coupled ambipolar genes. In this case, gene variability and selection of mutations should be interconnected in all opposite viral genes (in the case of influenza virus for NS1, NEP, and NSP8). These considerations incline to the assumption of the existence of a rule of reverse determination, when both ambipolar genes can have linked structural motives and functions. Further studies are necessary to clarify this idea.

Ambisense stacking of genes revealed in coronavirus and influenza virus genomes significantly increases virus diversity, genetic potential and extend virus-host adaptation pathway possibilities. Existence of numerous ambisense genes opens up a new avenue for virus reproduction where one virus genome can produce a multiple progeny population of virions possessing identical genome RNA and different protein compositions. In this case, a part of virions decorated with one of the NGPs proteins (in the case of coronaviruses) could be hidden from us, as “the dark side of the Moon”. The expression of coronavirus “negative” and flu “positive” genes may have a host (tissue)-dependent regulation facilitating immune escape of overcovered virions and specific pathogenetic pathways in the host(s) where the up-expression of the virus NGP or NSP genes occurs. Further studies will shed light on this ambisense concept of human and animal orthomyxo- and coronaviruses.

For the current time, there are four ambisense virus genera (phlebo-, tospo-, arena-, and bunyaviruses), which are well known to realize both positive- and negative-sense genome RNA strategies to encode viral proteins[12,21]. Ambisense genes of these virus genera locate in separate areas of the genome RNA without their overlapping and stacking. The ambisense genes locating in the genome in the stacking manner were found in influenza viruses, in which, similarly to coronaviruses, direct expression of these genes has not yet been identified, but there are indirect signs of such expression during natural viral infection in vivo[12-14]. Location of genes with opposite polarity in the same region of the RNA molecule makes it possible to significantly increase the genetic capacity of the viral genome and opens new ways for virus diversity, increasing virus adaptability to the host and biological evolution in nature[15]. The presence of potential ambisense genes in genomes of influenza and coronaviruses raises the question of the classification of these families. The detection in infected cells or infected organisms of protein products expressed by the ambisense manner will give grounds for classifying the coronavirus and orthomyxovirus families as the ambisense viruses with a bipolar genome strategy.

The manuscript data suggest that ambisense gene stacking in influenza and coronavirus families significantly increases genetic potential and virus diversity to extend virus-host adaptation pathways in nature. These data imply that ambisense viruses may have a multivirion mechanism, like "a dark side of the Moon", allowing production of the heterogeneous population of virions expressed through positive and negative sense genome strategies.

Zhirnov O acknowledges academicians Lvov DK and Georgiev GP for the support of this work and Dr. Chernyshova A for assistance with figures preparation.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Virology

Country/Territory of origin: Russia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cao G S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Pinto RM, Lycett S, Gaunt E, Digard P. Accessory Gene Products of Influenza A Virus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Woo PC, Huang Y, Lau SK, Yuen KY. Coronavirus genomics and bioinformatics analysis. Viruses. 2010;2:1804-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 624] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhirnov OP, Poyarkov SV, Vorob'eva IV, Safonova OA, Malyshev NA, Klenk HD. Segment NS of influenza A virus contains an additional gene NSP in positive-sense orientation. Dokl Biochem Biophys. 2007;414:127-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gong YN, Chen GW, Chen CJ, Kuo RL, Shih SR. Computational analysis and mapping of novel open reading frames in influenza A viruses. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhirnov OP. Unique Bipolar Gene Architecture in the RNA Genome of Influenza A Virus. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2020;85:387-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Baez M, Zazra JJ, Elliott RM, Young JF, Palese P. Nucleotide sequence of the influenza A/duck/Alberta/60/76 virus NS RNA: conservation of the NS1/NS2 overlapping gene structure in a divergent influenza virus RNA segment. Virology. 1981;113:397-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Clifford M, Twigg J, Upton C. Evidence for a novel gene associated with human influenza A viruses. Virol J. 2009;6:198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang CW, Chen MF. Uncovering the Potential Pan Proteomes Encoded by Genomic Strand RNAs of Influenza A Viruses. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sabath N, Morris JS, Graur D. Is there a twelfth protein-coding gene in the genome of influenza A? J Mol Evol. 2011;73:305-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhirnov OP, Akulich KA, Lipatova AV, Usachev EV. Negative-sense virion RNA of segment 8 (NS) of influenza a virus is able to translate in vitro a new viral protein. Dokl Biochem Biophys. 2017;473:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhirnov OP, Klenk HD. [Integration of influenza A virus NSP gene into baculovirus genome and its expression in insect cells]. Vopr Virusol. 2010;55:4-8. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hickman HD, Mays JW, Gibbs J, Kosik I, Magadán JG, Takeda K, Das S, Reynoso GV, Ngudiankama BF, Wei J, Shannon JP, McManus D, Yewdell JW. Correction: Influenza A Virus Negative Strand RNA Is Translated for CD8+ T Cell Immunosurveillance. J Immunol. 2018;201:2187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. |

Zhirnov OP, Konakova TE, Anhlan D, Ludwig S, Isaeva EI, Cellular immune response in infected mice to nsp protein encoded by the negative strand NS RNA of influenza A virus.

|

| 14. | Zhong W, Reche PA, Lai CC, Reinhold B, Reinherz EL. Genome-wide characterization of a viral cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope repertoire. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45135-45144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhirnov OP, Poyarkov SV. Novel Negative Sense Genes in the RNA Genome of Coronaviruses. Dokl Biochem Biophys. 2021;496:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhirnov OP. Molecular Targets in the Chemotherapy of Coronavirus Infection. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2020;85:523-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kearse MG, Wilusz JE. Non-AUG translation: a new start for protein synthesis in eukaryotes. Genes Dev. 2017;31:1717-1731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bartas M, Adriana Volná A, Červeň J, Brázda V, Pečinka P. Unheeded SARS-CoV-2 protein? Look deep into negative-sense RNA. 2020 Preprint. Available from: bioRxiv:2020.11.27.400788. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Zhirnov OP, Poyarkov SV. Unknown negative genes in the positive RNA genomes of coronaviruses. Authorea. 2020;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Zhirnov OP, Vorobjeva IV, Saphonova OA, Poyarkov SV, Ovcharenko AV, Anhlan D, Malyshev NA. Structural and evolutionary characteristics of HA, NA, NS and M genes of clinical influenza A/H3N2 viruses passaged in human and canine cells. J Clin Virol. 2009;45:322-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nguyen M, Haenni AL. Expression strategies of ambisense viruses. Virus Res. 2003;93:141-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kolekar P, Pataskar A, Kulkarni-Kale U, Pal J, Kulkarni A. IRESPred: Web Server for Prediction of Cellular and Viral Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES). Sci Rep. 2016;6:27436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |